Luhansk People's Republic

The Luhansk People's Republic, alternatively spelled as Lugansk People's Republic[7][13] (Russian: Луга́нская Наро́дная Респу́блика, tr. Luganskaya Narodnaya Respublika, IPA: [lʊˈɡanskəjə nɐˈrodnəjə rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə]), usually abbreviated as LPR or LNR, is a landlocked proto-state. It is located in Luhansk Oblast in the Donbass region, a territory internationally recognized to be a part of Ukraine. Luhansk is its capital and biggest city. The population of the republic is approximately 1.5 million people. In its constitution, LPR is proclaimed to be a democratic constitutional state.[14] The current head of state is Leonid Pasechnik.

Luhansk People's Republic

| |

|---|---|

Anthem: "Anthem of the Luhansk People's Republic" (Гимн Луганской Народной Республики) | |

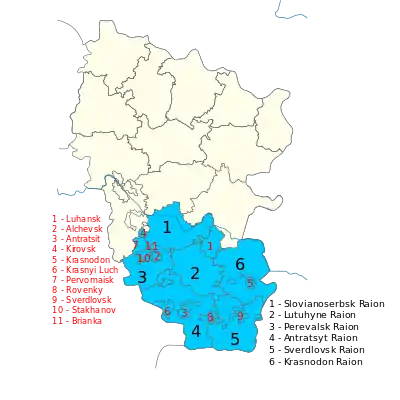

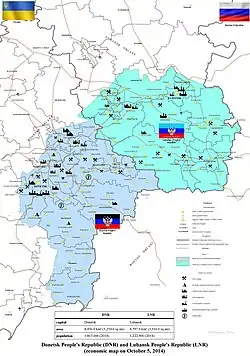

Declared (light green and dark green) and controlled territory (dark green) of the LPR | |

_(semi-secession).svg.png.webp) Lugansk People's Republic in Ukraine | |

| Status | Unrecognized proto-state. Recognized by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262 as part of Ukraine |

| Capital and largest city | Luhansk |

| Official language | Russian[5] |

| Government | Republic |

• Head | Leonid Pasechnik[6] |

• Prime Minister | Sergey Kozlov |

• Chairman of the People's Council | Denis Miroshnichenko (acting)[7] |

| Legislature | People's Council |

| Independence from Ukraine | |

• Established | 27 April 2014 |

• Declaration of Independence | 12 May 2014[8] |

• Signing of Minsk II agreement | 11 February 2015 |

| Area | |

• Total | 8,377[9] km2 (3,234 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 1,464,039[10] |

| Currency | Russian ruble (most common); Ukrainian hryvnia (less common); euro, U.S. dollar (legal but rarely used)[11] |

| Time zone | UTC+3[12] |

The LPR declared independence from Ukraine in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, along with Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) and the Republic of Crimea. An ongoing armed conflict with Ukraine followed its declaration of independence. The LPR and DPR receive humanitarian assistance from Russia. According to NATO and Ukraine, Russia had also provided military aid to the rebels, a claim that Russia denies.[15][16][17][18]

Ukraine's legislation describes the LPR's area as a "temporarily occupied territory", and the government of LPR is described as an occupying administration of the Russian Federation.[19][20] The September 2014 Minsk agreement signed by representatives of the OSCE, Ukraine, and Russia—and by the heads of the LNR and DNR without recognizing any status for them—[21][22][23] was meant to stop the conflict and reintegrate rebel-held territory into Ukraine in exchange for more autonomy for the area, but the agreement was never fully implemented.[24]

LPR remains unrecognized by any UN member state, including Russia – although Russia recognizes documents issued by the LPR government, such as identity documents, diplomas, birth and marriage certificates, and vehicle registration plates.[25]

Geography and demographics

The LPR is landlocked and borders Ukraine (i.e., the rest of Ukraine) to the north, the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic to the west, and Russia to the east. The LPR extends to approximately half of Luhansk Oblast, including its densely populated areas, the regional capital Luhansk, as well as the major cities Alchevsk and Krasnodon. Approximately 64.4% of the population of the Oblast lives in the LPR.[26] The northern part of Luhansk Oblast, has remained under Ukrainian control since 2014-2015. [27] The territory controlled by the LPR is mostly, but not completely, coincident with the right (southern) bank of the Donets.

The highest point of the LPR (and of the whole Donbass) is Grave Mechetna hill (367.1 m (1,204 ft) above sea level), which is located in the vicinity of the city of Petrovske.[28]

The population of the republic is estimated by the LPR's bureau of statistics at approximately 1.5 million people, although the exactness of this estimate is questionable due to wartime migration and a lack of independent sources.[10] Approximately 435,000 of the republic's population live in Luhansk,[29] where the republic has its administration.

History

Luhansk and Donetsk People's republics are located in the historical region of Donbass, which was added to Ukraine in 1922.[30] The majority of the population speaks Russian as their first language. Attempts by various Ukrainian governments to question the legitimacy of the Russian culture in Ukraine had since the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine often resulted in political conflict. In the Ukrainian national elections, a remarkably stable pattern had developed, where Donbass and the Western Ukrainian regions had voted for the opposite candidates since the presidential election in 1994. Viktor Yanukovych, a Donetsk native, had been elected as a president of Ukraine in 2010. His overthrow in the 2014 Ukrainian revolution led to protests in Eastern Ukraine, which gradually escalated into an armed conflict between the newly formed Ukrainian government and the local armed militias.[31]

Occupation of government buildings

On 5 March 2014, 12 days after the protesters in Kyiv seized the president's office (at the time Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych had already fled Ukraine[32]),[33] a crowd of people in front of the Luhansk Oblast State Administration building proclaimed Aleksandr Kharitonov as "People's Governor" in Luhansk region. On 9 March 2014 Luganskaya Gvadiya of Kharitonov stormed the government building in Luhansk and forced the newly appointed Governor of Luhansk Oblast, Mykhailo Bolotskykh, to sign a letter of resignation.[34]

One thousand pro-Russian activists seized and occupied the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) building in the city of Luhansk on 6 April 2014, following similar occupations in Donetsk and Kharkiv.[35][36] The activists demanded that separatist leaders who had been arrested in previous weeks be released.[35] In anticipation of attempts by the government to retake the building, barricades were erected to reinforce the positions of the activists.[37][38] It was proposed by the activists that a "Lugansk Parliamentary Republic" be declared on 8 April 2014, but this did not occur.[39][40] By 12 April, the government had regained control over the SBU building with the assistance of local police forces.[41]

Several thousand protesters gathered for a 'people's assembly' outside the regional state administration (RSA) building in Luhansk city on 21 April. These protesters called for the creation of a 'people's government', and demanded either federalisation of Ukraine or incorporation of Luhansk into the Russian Federation.[42] They elected Valery Bolotov as 'People's Governor' of Luhansk Oblast.[43] Two referendums were announced by the leadership of the activists. One was scheduled for 11 May, and was meant to determine whether the region would seek greater autonomy (and potentially independence), or retain its previous constitutional status within Ukraine. Another referendum, meant to be held on 18 May in the event that the first referendum favoured autonomy, was to determine whether the region would join the Russian Federation, or become independent.[44]

During a gathering outside the RSA building on 27 April 2014, pro-Russian activists proclaimed the "Luhansk People's Republic".[45] The protesters issued demands, which said that the Ukrainian government should provide amnesty for all protesters, include the Russian language as an official language of Ukraine, and also hold a referendum on the status of Luhansk Oblast.[45] They then warned the Ukrainian government that if it did not meet these demands by 14:00 on 29 April, they would launch an armed insurgency in tandem with that of the Donetsk People's Republic (DPR).[45][46] As the Ukrainian government did not respond to these demands, 2,000 to 3,000 activists, some of them armed, seized the RSA building, and a local prosecutor's office, on 29 April.[47] The buildings were both ransacked, and then occupied by the protesters.[48] Protestors waived local flags, alongside those of Russia and the neighbouring Donetsk People's Republic.[49] The police officers that had been guarding the building offered little resistance to the takeover, and some of them defected and supported the activists.[50]

Territorial expansion

Demonstrations by pro-Russian activists began to spread across Luhansk Oblast towards the end of April. The municipal administration building in Pervomaisk was overrun on 29 April 2014, and the Luhansk People's Republic (LPR) flag was raised over it.[51][52] Oleksandr Turchynov, then acting president of Ukraine, admitted the next day that government forces were unable to stabilise the situation in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.[53] On the same day, activists seized control of the Alchevsk municipal administration building.[54][55] In Krasnyi Luch, the municipal council conceded to demands by activists to support the 11 May 2014 referendum, and followed by raising the Russian flag over the building.[51]

Insurgents occupied the municipal council building in Stakhanov on 1 May 2014. Later in the week, they stormed the local police station, business centre, and SBU building.[56][57] Activists in Rovenky occupied a police building there on 5 May, but quickly left.[58] On the same day, the police headquarters in Slovianoserbsk was seized by members of the Army of the South-East, a pro-Russian Luhansk regional militia group.[59][60] In addition, the town of Antratsyt was occupied by the Don Cossacks.[61][62] Some said that the occupiers came from Russia;[63] the Cossacks themselves said that only a few people among them had come from Russia.[64] On 7 May, insurgents also seized the prosecutor's office in Sievierodonetsk.[65] Luhansk People's Republic supporters stormed government buildings in Starobilsk on 8 May, replacing the Ukrainian flag with that of the Republic.[66] Sources within the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs said that as of 10 May 2014, the day before the proposed status referendum, Ukrainian forces still retained control over 50% of Luhansk Oblast.[67]

Status referendum

The planned referendum on the status of Luhansk oblast was held on 11 May 2014.[68] The organisers of the referendum said that 96.2% of those who voted were in favour of self-rule, with 3.8% against.[69] They said that voter turnout was at 81%. There were no international observers present to validate the referendum.[69]

Declaration of independence

Following the referendum, the head of the Republic, Valery Bolotov, said that the Republic had become an "independent state".[70] The still-extant Luhansk Oblast Council did not support independence, but called for immediate federalisation of Ukraine, asserting that "an absolute majority of people voted for the right to make their own decisions about how to live".[71][72] The council also requested an immediate end to Ukrainian military activity in the region, amnesty for anti-government protestors, and official status for the Russian language in Ukraine.[72] Valery Bolotov was wounded in an assassination attempt on 13 May.[73] Luhansk People's Republic authorities blamed the incident on the Ukrainian government. Government forces later captured Alexei Rilke, the commander of the Army of the South-East.[74] The next day, Ukrainian border guards arrested Valery Bolotov. Just over two hours later, after unsuccessfully attempting negotiations, 150 to 200 armed separatists attacked the Dovzhansky checkpoint where he had been held. The ensuing firefight led Ukrainian government forces to free Bolotov.[75]

On 24 May 2014 the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic jointly announced their intention to form a confederative "union of People's Republics" called New Russia.[76] Republic President Valery Bolotov said on 28 May that the Luhansk People's Republic would begin to introduce its own legislation based on Russian law; he said Ukrainian law was unsuitable due to it being "written for oligarchs".[77] Vasily Nikitin, prime minister of the Republic, announced that elections to the State Council would take place in September.[78]

The leadership of the Luhansk People's Republic said on 12 June 2014 that it would attempt to establish a "union state" with Russia.[79] The government added that it would seek to boost trade with Russia through legislative, agricultural and economic changes.[79]

Stakhanov, a city that had been occupied by LPR-affiliated Don Cossacks, seceded from the Luhansk People's Republic on 14 September 2014.[80] Don Cossacks there proclaimed the Republic of Stakhanov, and said that a "Cossack government" now ruled in Stakhanov.[80][81] However the following day this was claimed to be a fabrication, and an unnamed Don Cossack leader stated the 14 September meeting had, in fact, resulted in 12,000 Cossacks volunteering to join the LPR forces.[82] Elections to the LPR Supreme Council took place on 2 November 2014, as the LPR did not allow the Ukrainian parliamentary election to be held in territory under its control.[83][84]

Human rights in the early stages of the war

In May 2014 the United Nations observed an "alarming deterioration" of human rights in insurgent-held territory in eastern Ukraine.[85] The UN detailed growing lawlessness, documenting cases of targeted killings, torture, and abduction, carried out by Luhansk People's Republic insurgents.[86] The UN also highlighted threats, attacks, and abductions of journalists and international observers, as well as the beatings and attacks on supporters of Ukrainian unity.[86] An 18 November 2014 United Nations report on eastern Ukraine declared that the Luhansk People's Republic was in a state of "total breakdown of law and order".[87] The report noted "cases of serious human rights abuses by the armed groups continued to be reported, including torture, arbitrary and incommunicado detention, summary executions, forced labour, sexual violence, as well as the destruction and illegal seizure of property may amount to crimes against humanity".[87] The report also stated that the insurgents violated the rights of Ukrainian-speaking children because schools in rebel-controlled areas only teach in Russian.[87] The United Nations also accused the Ukrainian Army and Ukrainian (volunteer) territorial defense battalions of human rights abuses such as illegal detention, torture and ill-treatment, noting official denials.[87] In a 15 December 2014 press conference in Kyiv UN Assistant Secretary-General for human rights Ivan Šimonović stated that the majority of human rights violations, including executions without trial, arrests and torture, were committed in areas controlled by pro-Russian rebels.[88]

In November 2014, Amnesty International called the "People's Court" (public trials where allegedly random locals are the jury) held in the Luhansk People's Republic "an outrageous violation of the international humanitarian law".[89]

In January 2015, the Luhansk Communist Party criticised the current situation in the region. In their statement they expressed "deep disappointment" with how the situation developed from "authentic people's protests a year ago" to "return of corruption and banditism".[90] In December 2015 the Special Monitoring Mission of the OSCE in Ukraine reported "Parallel 'justice systems' have begun operating" in territory controlled by the Luhansk People's Republic.[91] They criticized this judiciary to be "non-transparent, subject to constant change, seriously under-resourced and, in many instances, completely non-functional".[91]

Luhansk People's Republic since 2015

On 1 January 2015, forces loyal to the Luhansk People's Republic ambushed and killed Alexander Bednov, head of a pro-Russian battalion called "Batman". Bednov was accused of murder, abduction and other abuses. An arrest warrant for Bednov and several other battalion members had been previously issued by the separatists' prosecutor's office.[92][93][94]

On 12 February 2015, DPR and LPR leaders Alexander Zakharchenko and Igor Plotnitsky signed the Minsk II agreement.[22] In the Minsk agreement it is agreed to introducing amendments to the Ukrainian constitution "the key element of which is decentralisation" and the holding of elections "on temporary order of local self-governance in particular districts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, based in the line set up by the Minsk Memorandum as of 19 September 2014"; in return rebel held territory would be reintegrated into Ukraine.[22][23] Representatives of the DPR and LPR continue to forward their proposals concerning Minsk II to the Trilateral Contact Group on Ukraine.[95] Plotnitsky told journalists on 18 February 2015: "Will we be part of Ukraine? This depends on what kind of Ukraine it will be. If it remains like it is now, we will never be together."[96]

On 20 May 2015, the leadership of the Federal State of Novorossiya announced the termination of the confederation 'project'.[97]

On 19 April 2016, planned (organised by the LPR) local elections were postponed from 24 April to 24 July 2016.[98] On 22 July 2016, this elections was again postponed to 6 November 2016.[99] (On 2 October 2016, the DPR and LPR held "primaries" in were voters voted to nominate candidates for participation in the 6 November 2016 elections.[100] Ukraine denounced these "primaries" as illegal.[100]) On 4 November 2016, both DPR and LPR postponed their 6 November 2016 local elections "until further notice".

The "LPR Prosecutor General's Office" announced late September 2016, that it had thwarted a coup attempt ringleaded by former LPR appointed prime minister Gennadiy Tsypkalov (who they stated had committed suicide on 23 September while in detention).[101] Meanwhile, it had also imprisoned former LPR parliamentary speaker Aleksey Karyakin and former LPR interior minister, Igor Kornet.[102] DPR leader Zakharchenko said he had helped to thwart the coup (stating "I had to send a battalion to solve their problems").[102]

On 4 February 2017, LPR defence minister Oleg Anashchenko was killed in a car bomb attack in Luhansk.[103] Separatists claimed "Ukrainian secret services" were suspected of being behind the attack; while Ukrainian officials suggested Anashchenko's death may be the result of an internal power struggle among rebel leaders.[103]

Mid-March 2017 Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a decree on a temporary ban on the movement of goods to and from territory controlled by the self-proclaimed Luhansk People's Republic and Donetsk People's Republic; this also means that since then Ukraine does not buy coal from the Donets Black Coal Basin.[104]

On 21 November 2017, armed men in unmarked uniforms took up positions in the center of Luhansk in what appeared to be a power struggle between the head of the republic Plotnitsky and the (sacked by Plotnitsky) LPR appointed interior minister Igor Kornet.[105][106] Media reports stated that the DPR had sent armed troops to Luhansk the following night.[105][106] Three days later the website of the separatists stated that Plotnitsky had resigned "for health reasons. Multiple war wounds, the effects of blast injuries, took their toll."[6] The website stated that security minister Leonid Pasechnik had been named acting leader "until the next elections."[6] Plotnitsky was stated to become the separatist's representative to the Minsk process.[6] Plotnitsky himself did not issue a public statement on 24 November 2017.[6] Russian media reported that Plotnitsky had fled the unrecognised republic on 23 November 2017, first travelling from Luhansk to Rostov-on-Don by car and then flying to Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport.[107] On 25 November the 38-member separatist republic's People's Council unanimously approved Plotnitsky's resignation.[108] Pasechnik declared his adherence to the Minsk accords, claiming "The republic will be consistently executing the obligations taken under these agreements."[7] In the summer of 2019, when talking about a "special status" for the LPR, Pasechnik stated it "is not an autonomy. It does not mean, we will return back into Ukraine. This is the only way to stop this madness, this war. You should understand that we, as a sovereign state will be a state within the state – that will be our special status.”[109]

In early June 2020, the LPR declared Russian as the only state language on its territory, removing the Ukrainian language from its school curriculum.[110] Previously the separatists leaders had made Ukrainian LPR's second state language, but in practice it was already disappearing from schools curricula prior to June 2020.[111]

In January 2021 the Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic stated in a "doctrine Russian Donbass" that they aimed to size all of the territories of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast under control by the Ukrainian government "in the near future."[112] The document did not specifically state the intention of DPR and LPR to be annexed by Russia.[112]

Administrative divisions

Since late 2014, the Luhansk People's Republic controls the following administrative divisions of Luhansk Oblast:[113][114]

- Luhansk Municipality

- Alchevsk

- Antratsyt Municipality

- Brianka Municipality

- Kirovsk Municipality

- Krasnodon Municipality

- Krasnyi Luch Municipality

- Pervomaysk

- Rovenky Municipality

- Stakhanov Municipality

- Sverdlovsk Municipality

- Antratsyt Raion

- Krasnodon Raion

- Lutuhyne Raion

- Perevalsk Raion

- Slovianoserbsk Raion

- Sverdlovsk Raion

Government

Constitution

The People's Council of the LPR ratified a temporary constitution on 18 May 2014. Its government styles itself as a People's republic. The form of The Luhansk People's Republic's parliament is called the People's Council and has 50 deputies.[115] Aleksey Karyakin was elected as its first head on 18 May 2014.[102] Its anthem is "Glory to Luhansk People's Republic! (Russian: Луганской Народной Республике, Слава!, also known as Live and Shine, LNR)"[116][117]

Elections

The first parliamentary elections to the legislature of the Luhansk People's Republic were held on 2 November 2014.[115] People of at least 30 years old who "permanently resided in Luhansk People's Republic the last 10 years" were electable for four years and could be nominated by public organizations.[115] All residents of Luhansk Oblast were eligible to vote, even if they are residents of areas controlled by Ukrainian government forces or fled to Russia or other places in Ukraine as refugees.[83]

Ukraine urged Russia to use its influence to stop the election "to avoid a frozen conflict".[118] Russia on the other hand indicated it "will of course recognise the results of the election"; Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated that the election "will be important to legitimise the authorities there".[84] Ukraine held the 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election on 26 October 2014; these were boycotted by the Donetsk People's Republic and hence voting for it did not take place in Ukraine's eastern districts controlled by forces loyal to the Luhansk People's Republic.[84][118]

On 6 July 2015 the Luhansk People's Republic leader (LPR) Igor Plotnitsky set elections for "mayors and regional heads" for 1 November 2015 in territory under his control. (Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) leader Alexander Zakharchenko issued a decree on 2 July 2015 that ordered local DPR elections to be held on 18 October 2015. He said that this action was "in accordance with the Minsk agreements".[119]) On 6 October 2015 the DNR and LPR leadership postponed their planned elections to 21 February 2016.[120] This happened 4 days after a Normandy four meeting in which it was agreed that the October 2015 Ukrainian local elections in LPR and DPR controlled territories would be held in accordance to the February 2015 Minsk II agreement.[121] At the meeting President of France François Hollande stated that in order to hold these elections (in LPR and DPR controlled territories) it was necessary "since we need three months to organize elections" to hold these elections in 2016.[121] Also during the meeting it is believed that Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to use his influence to not allow the DPR and Luhansk People's Republic election to take place on 18 October 2015 and 1 November 2015.[121] On 4 November 2016 both DPR and LPR postponed their local elections, they had set for 6 November 2016, "until further notice".

Additional elections took place simultaneously in Donetsk and Luhansk republics on 11 November 2018. The official position of the U.S. and European union is that this vote is illegitimate because it was not controlled by the Ukrainian government, and that it was contrary to the 2015 Minsk agreement. Leonid Pasechnik, the head of the Luhansk People's Republic, disagreed and said that the vote was in accordance with the Minsk Agreement. The separatist leaders said that the election was a key step toward establishing full-fledged democracy in the regions. Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko said that residents of eastern Ukraine should not to participate in the vote. Nevertheless, both regions reported voter turnout of more than 70 percent as of two hours before the polls closed at 8 p.m. local time.[122][123][124]

Sexual minorities

There were reports in September 2014 claiming that the Parliament of the Luhansk People's Republic adopted a law that would introduce criminal liability for homosexuality. According to these reports, homosexuality was to be punishable by five years in prison or corrective labour for a term of two to four years.[125][126] No such law exists in the public record of the legislative assembly of the republic as of May 2018.[127] A law limiting the public expression of homosexuality was, however, adopted in March 2018.[128][129][130]

Currency

As of May 2015, pensions started being paid in mostly Russian rubles by the Luhansk People's Republic. 85% were in rubles, 12% in hryvnias, and 3% in dollars according to LPR Head Igor Plotnitsky.[131] Ukraine completely stopped paying pensions for the elderly and disabled in areas under DPR and LPR control on 1 December 2014.[132]

Military

Sports and culture

The football team of the Luhansk People's republic is ranked sixteenth in the Confederation of Independent Football Associations world ranking.[133] A football match between LPR and DPR was played on 8 August 2015 at the Metalurh Stadium in Donetsk.[134]

International relationships and recognition

The Luhansk People's Republic is not recognized by any UN member state. It has been recognized by two other states with limited international recognition: South Ossetia [135][136] and by Donetsk People's Republic.[137]

LPR has been in a state of armed conflict with the Ukraine since the former declared independence in 2014. The Ukrainian military operation against the republic is officially called an anti-terrorist operation, although it is not considered as such by the Supreme Court of Ukraine itself[138] or by either the EU, US, or Russia.[139][140][141]

The Russian Federation does not recognize LPR as a state, but it recognizes official documents issued by the LPR government, such as identity documents, diplomas, birth and marriage certificates and vehicle registration plates.[25] This recognition was introduced in February 2017 [25] and enabled people living in LPR controlled territories to travel, work or study in Russia.[25] According to the presidential decree that introduced it, the reason for the decree was "to protect human rights and freedoms" in accordance with "the widely recognized principles of international humanitarian law."[142] Ukrainian authorities decried the decree and claimed that it was contradictory to the Minsk II agreement, and also that it "legally recognised the quasi-state terrorist groups which cover Russia's occupation of part of Donbas."[143]

In 2019 leader of LPR Leonid Pasechnik expressed an intention to eventually rejoin Ukraine "as a sovereign state within the [Ukrainian] state".[109]

See also

- Donetsk People's Republic

- 2014 Luhansk status referendum

- 2014 pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine

- List of rebel groups that control territory

- List of active separatist movements in Europe

- Novorossiya (confederation)

References

- "'Luhansk People's Republic' announces total mobilization". Kyiv Post. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Luhans'k County (Ukraine)". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- "'Luhansk People's Republic' announces total mobilization". Kyiv Post. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "Luhans'k County (Ukraine)". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- Парламент ЛНР признал русский язык единственным государственным в республике [LPR legislature adopted Russian language as the sole state language of the republic] (in Russian). Interfax. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Ukraine rebel region's security minister says he is new leader , Reuters (24 November 2017)

Separatist Leader In Ukraine's Luhansk Resigns Amid Power Struggle, Radio Free Europe (24 November 2017) - Lugansk People’s Republic head resigns, TASS news agency (24 November 2017)

- "Luhansk region declares independence at rally in Luhansk". KyivPost. 12 May 2014.

- "ЭКОНОМИКА И ОБЩЕСТВО:ПРОБЛЕМЫ И ПЕРСПЕКТИВЫ РАЗВИТИЯВ УСЛОВИЯХ НЕОПРЕДЕЛЁННОСТИ" (PDF).

- "Population count of the Lugansk People's Republic on April 1st, 2018" (PDF). Committee of statistic of Lugansk People's Republic. 1 April 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- "The War republics in the Donbas one year after the outbreak of the conflict". 17 June 2015.

- "Russia Abandons Year-Round Summer Time". abcnews.go.com. 2 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- "Lugansk Media Centre". en.lug-info.com.

- "Конституция Луганской Народной Республики".

- Ukraine crisis: Russian troops crossed border, Nato says, BBC News (12 November 2014)

Putin defends rebel leaders in eastern Ukraine, BBC News (19 December 2019)

Ukraine conflict: Front-line troops begin pullout, BBC News (29 October 2019) - "Database and Video Overview of the Russian Weaponry in the Donbas". InformNapalm.org (English). 17 September 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Second Russian aid convoy arrives in Ukrainian city of Luhansk: agencies". Reuters. 13 September 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Lugansk Media Centre — Russian humanitarian aid convoy arrives in Lugansk". en.lug-info.com. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Law about occupied territories of Ukraine Mirror Weekly. 15 May 2014

- Higher educational institutions at the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine will not work – the minister of education. News. 1 October 2014

- "Minsk Protocol" (PDF). OSCE. 1 September 2014.

- "Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements" (Press release) (in Russian). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- "Minsk agreement on Ukraine crisis: text in full". The Daily Telegraph. 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Explainer: What Is The Steinmeier Formula -- And Did Zelenskiy Just Capitulate To Moscow?, Radio Free Europe (2 October 2019)

Ukraine conflict: Can peace plan in east finally bring peace?, BBC News (10 December 2020)

Ukraine conflict: Guns fall silent but crisis remains, BBC News (23 October 2015) - Putin orders Russia to recognize documents issued in rebel-held east Ukraine, Reuters (18 February 2017)

- "Self-proclaimed Luhansk People's Republic governs most residents". en.itar-tass.com. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- "'Luhansk Will Never Be The Same Again:' In Kyiv, A Blogger Reflects On His Native City". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "На даху Донбасу". Club-tourist. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "Four Years of the Luhansk People's Republic – Geopolitical Futures". Geopolitical Futures. 2 March 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- Andrés, César García (2018). "Historical Evolution of Ukraine and its Post Communist Challenges" (PDF). Revista de Stiinte Politice (RST). 58.

- Petro, Nicolai N., Understanding the Other Ukraine: Identity and Allegiance in Russophone Ukraine (1 March 2015). Richard Sakwa and Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska, eds., Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives, Bristol, United Kingdom: E-International Relations Edited Collections, 2015, pp. 19–35. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2574762

- Ukraine Leader Was Defeated Even Before He Was Ousted, New York Times (3 January 2015)

- "Protesters seize Ukraine president's office, take control of Kiev". Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Nikulenko, T. The SBU Colonel Zhyvotov: with torture they were forcing the father of former chief of Luhansk SBU to convince his son to come to Donetsk, and when he refused, they killed him (Полковник СБУ Животов: Отца экс-главы Луганской СБУ пытками принуждали вызвать сына в Донецк, а когда он отказался – убили). Gordon.ua. 2 November 2016

- "Ukraine's eastern hot spots – GlobalPost". GlobalPost. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Over a dozen towns held by pro-Russian rebels in east Ukraine & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Возле СБУ в Луганске готовятся к штурму и продолжают укреплять баррикады (фото)". 8 April 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "The Ukraine crisis: Boys from the blackstuff – The Economist". The Economist. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Здание луганской СБУ удерживают полторы тысячи вооруженных сепаратистов – журналист : Новости УНИАН". Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "There's Violence on the Streets of Ukraine—and in Parliament A news roundup for April 8". The New Republic. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Alan Yuhas. "Crisis in east Ukraine: a city-by-city guide to the spreading conflict". the Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Luhansk". Interfax-Ukraine. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "В Луганске выбрали "народного губернатора" – Донбасс – Вести". Вести. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "У Луганську сепаратисти вирішили провести два референдуми — Українська правда". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "TASS: World – Federalization supporters in Luhansk proclaim people's republic". TASS. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine – based on information received up until 28 April 2014, 19:00 (Kyiv time) – OSCE". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Ukraine crisis: Pro-Russia activists take Luhansk offices". BBC News Europe. 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine – based on information received up until 29 April 2014, 19:00 (Kyiv time) – OSCE". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Luhansk". Interfax-Ukraine. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "В Луганске сепаратисты взяли штурмом ОГА, правоохранители перешли на сторону митингующих : Новости УНИАН". Ukrainian Independent Information Agency. 29 April 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "Красный Луч и Первомайск "слились". Кто дальше? — Новости Луганска и Луганской области — Луганский Радар". Lugradar.net. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Автор: Ищук. "Сепаратисты захватили горсовет Первомайска в Луганской области, — СМИ | Новости. Новости дня на сайте Подробности". Podrobnosti.ua. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Ukraine unrest: Kiev 'helpless' to quell parts of east". BBC News. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

I would like to say frankly that at the moment the security structures are unable to swiftly take the situation in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions back under control … More than that, some of these units either aid or co-operate with terrorist groups

- Jade Walker (30 April 2014). "Ukraine Unrest: Separatists Seize Buildings In Horlivka". Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Maidan opponents seize Alchevsk city council – media – News – Politics – The Voice of Russia: News, Breaking news, Politics, Economics, Business, Russia, International current events, Expert opinion, podcasts, Video". The Voice of Russia. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- В Стаханове вооруженные люди ограбили "Бизнес-центр" [In Stakhanov, armed people robbed the "Business Center"] (in Russian). V-variant.lg.ua. 7 May 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Dabagian, Stepan (7 May 2014). 'Никаких националистических идей у нас нет. Мы просто за единую Украину и не хотим в Россию' [We have no nationalistic ideas. We are simply for a united Ukraine and do not want to become part of Russia] (in Russian). Fakty.ua. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "Жительница города Ровеньки: "Люди не понимают, что такое "Луганская республика", но референдума хотят" (Люди рассказывают, что не доверяют новой власти, ждут, когда их освободят от "нехороших людей", и хотят остаться в составе Украины)". Gigamir.net. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Славяносербская милиция перешла на сторону сепаратистов — Новости Луганска и Луганской области — Луганский Радар". Lugradar.net. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "МВД Украины заявило о захвате милиции Славяносербска — Газета.Ru | Новости". Gazeta.ru. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Город Антрацит взяли под контроль донские казаки — источник". Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Донские казаки взяли под контроль город Антрацит на Луганщине ›". Mr7.ru. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Putin's Tourists Enter Ukraine – Dmitry Tymchuk". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Shaun Walker. "Ukraine border guards keep guns trained in both directions". the Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Северодонецк: сепаратисты захватили здание прокуратуры " ИИИ "Поток" | Главные новости дня". Potok.ua. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "КИУ: Вчера в Старобельске штурмовали райгосадминистрацию". Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Украинские силовики взяли под контроль большую часть Луганской области — источник — Обозреватель". Obozrevatel.com. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Явка на референдуме в Луганской области превысила 75% :: Политика". Top.rbc.ru. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- "Ukraine crisis: Will the Donetsk referendum matter?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Separatists Declare Independence Of Luhansk Region". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Luhansk Regional Council demands Ukraine's immediate federalization". KyivPost. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Luhansk". Interfax-Ukraine. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Luhansk separatists say their chief wounded in assassination attempt". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "Avakov Announces Capture of the 'Commander of the Army of the South-East'". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Luhansk separatist leader Bolotov free in Ukraine after suspicious 'shootout'". KyivPost. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Луганская и Донецкая республики объединились в Новороссию". Novorossia. 24 May 2014.

- "Lugansk People's Republic wants to rewrite its laws according to Russian model". The Voice of Russia. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- "Ukraine's Lugansk plans to hold parliamentary elections in Sept". GlobalPost. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- Тезисы К Программе Первоочередных Действий Правительства Народной Республики [Theses for Priority Actions Programme for the Government of the People's Republic]. lugansk-online.info (in Russian). Archived from the original on 12 June 2014.

- "Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine based on information received as of 18:00 (Kyiv time), 16 September 2014" (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine based on information received as of 18:00 (Kyiv time), 15 September 2014" (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine based on information received as of 18:00 (Kyiv time), 18 September 2014" (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- LPR Head: Election to Remove Doubts Surrounding Legitimacy of Luhansk Authorities, 27 September 2014, RIA Novosti (27 September 2014)

- Ukraine crisis: Russia to recognise rebel vote in Donetsk and Luhansk, BBC News (28 October 2014)

- "Ukraine crisis: UN sounds alarm on human rights in east". BBC News. 16 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 15 May 2014.

- Almost 1,000 dead since east Ukraine truce – UN, BBC News (21 November 2014)

Ukraine death toll rises to more than 4,300 despite ceasefire – U.N., Reuters (21 November 2014) - Majority of human rights violations in Ukraine committed by militants – UN, Interfax-Ukraine (15 December 2014)

- Amnesty International alarmed by extrajudicial killings in self-proclaimed Luhansk republic, Interfax-Ukraine (14 November 2014)

Rebels in Ukraine 'post video of people’s court sentencing man to death', The Daily Telegraph (31 October 2014)

Ukraine conflict: Summary justice in rebel east, BBC News (3 November 2014) - "Комсомол Луганска — в борьбе за Единую Украину!" [Luhansk Komsomol for united Ukraine] (in Russian). Ленинский Коммунистический Союз Молодежи Украины. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Non-transparent 'justice systems' set up in rebel-controlled Donbas areas mostly non-functional – OSCE SMM, Interfax-Ukraine (25 December 2015)

- "Abuse, torture revealed at separatists' prison in Luhansk". Kyiv Post. 3 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- East Ukraine summit looks unlikely to happen as violence spikes in region, The Guardian (11 January 2015)

- Ukraine Rebel 'Batman' Battalion Commander Killed, New York Times (4 January 2015)

- Donetsk, Luhansk republics say election proposals forwarded to Contact Group on Ukraine, Russian News Agency "TASS" (12 May 2015)

Analysis: Donetsk and Luhansk propose amendments to Ukraine’s Constitution, The Ukrainian Weekly (22 May 2015)

"LNR" and "DNR" agree to a special status within Ukraine Donbass, Ukrayinska Pravda (9 June 2015) - Militia leader not sure if unrecognized Luhansk republic will remain part of "new Ukraine". TASS. 18 February 2015.

- "Russian-backed 'Novorossiya' breakaway movement collapses". Ukraine Today. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

Проект "Новороссия" закрыт [Project "New Russia" is closed]. Gazeta.ru. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015. - "Местные выборы в ЛНР перенесены на 24 июля". 19 April 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- (in Ukrainian) Zakharchenko postponed elections "DNR" in November. Ukrayinska Pravda (23 July 2016)

(in Ukrainian) Militants "LPR" also decided to move their "elections". Ukrayinska Pravda (24 July 2016) - Defying Minsk process, Russian-backed separatists hold illegal elections, Kyiv Post (2 October 2016)

Donbass militia leader announces autumn primaries in Donetsk, TASS news agency (23 May 2016) - LPR reports one of its former 'officials' Tsypkalov commits suicide, Interfax-Ukraine (24 September 2016)

- Ukrainian rebel leaders divided by bitter purge, Washington Post (3 October 2016)

- Ukraine conflict: Rebel commander killed in bomb blast, BBC News (4 February 2017)

- Ukrainian energy industry: thorny road of reform, UNIAN (10 January 2018)

- "Kremlin 'Following' Situation In Ukraine's Russia-Backed Separatist-Controlled Luhansk". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- "Luhansk coup attempt continues as rival militia occupies separatist region".

- "Захар Прилепин встретил главу ЛНР в самолете в Москву". Meduza.io.

- Народный совет ЛНР единогласно проголосовал за отставку Плотницкого (in Russian). Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Donbas: The new repertoire, The Ukrainian Week (28 September 2019)

- "Ukrainian language removed from schools in Russian proxy Luhansk 'republic'". Human Rights in Ukraine. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "«Через дискримінацію російської»: в окупованому «виші» остаточно скасували українську" [“Due to Russian discrimination”: in the occupied “higher education” the Ukrainian was finally abolished] (in Ukrainian). Radio Free Europe. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- (in Ukrainian) Militants presented the "doctrine": provides capture of all Donbass, Ukrayinska Pravda (28 January 2021)

- Кабмин назвал города Донбасса, подконтрольные сепаратистам (in Russian). Корреспондент. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Численность населения по состоянию на 1 октября 2015 года по Луганской Народной Республике [The population as of 1 October 2015 per the Lugansk People's Republic] (PDF) (in Russian). Luhansk People's Republic. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- "Date of elections in Donetsk, Luhansk People's republics the same – Nov. 2", Russian News Agency "TASS" (11 October 2014)

- "В ЛНР утвердили официальный гимн республики (аудио)". 29 April 2016.

- Закон «О Государственном гимне Луганской Народной Республики»

- Ukraine urges Russia to stop separatist elections, USA TODAY (21 October 2014)

- Local elections in DPR to take place on October 18 – Zakharchenko, Interfax-Ukraine (2 July 2015)

DPR, "LPR attempts to hold separate elections in Donbas on Oct 18 to have destructive consequences – Poroshenko", Interfax-Ukraine (2 July 2015) - Pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine postpone disputed elections, Reuters (6 October 2015)

Ukraine rebels to delay elections, Washington Post (6 October 2015) - Ukraine crisis: Pro-Russian rebels 'delay disputed elections', BBC News (6 October 2015)

Hollande: Elections In Eastern Ukraine Likely To Be Delayed, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (2 October 2015)

Ukraine Is Being Told to Live With Putin, Bloomberg News (5 October 2015) - hermesauto (11 November 2018). "Ukraine rebels hold elections in defiance of West". The Straits Times. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Ukraine Rebel Regions Vote in Ballot That West Calls Bogus". Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Khalil, Rania. "LPR Election Commission Delivers Accreditations To Int'l Observers Ahead Of Sunday's Vote". Pakistan Point.

- "Is the self-proclaimed LPR introduced "criminal liability for homosexuality"?". Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Ukraine Rebels Love Russia, Hate Gays, Threaten Executions". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- design.lg.ua. "Законы". nslnr.su. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- "Lugansk Media Centre – LPR passes law banning gay propaganda to minors". en.lug-info.com. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- design.lg.ua. "О внесении изменений в Закон Луганской Народной Республики "О защите детей от информации, причиняющей вред их здоровью и развитию"". nslnr.su. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- design.lg.ua. "О защите детей от информации, причиняющей вред их здоровью и развитию". nslnr.su. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- Yulia Surkova & Daryna Krasnolutska (4 May 2015). "Forget Tanks. Russia's Ruble Is Conquering Eastern Ukraine". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- Ian Bateson (12 November 2014). "Donbas civil society leaders accuse Ukraine of 'declaring war' on own people". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- "Luhansk People's Republic". CONIFA. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Ukraine's First Separatist Football Derby". Sports. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- South Ossetia Recognizes 'Luhansk People's Republic', Radio free Europe (19 June 2014)

- Ukraine’s rebel ‘people’s republics’ begin work of building new states, The Guardian (6 November 2014)

- "General Information". Official site of the head of the Lugansk People's Republic. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Supreme Court of Ukraine". Єдиний державний реєстр судових рішень (ЄДРСР). Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/fight-against-terrorism/terrorist-list/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "EU terrorist list – Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Международные террористические организации | Интернет-портал Национального антитеррористического комитета". 2 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Putin Signs Decree Temporarily Recognizing Passports Issued By Separatists In Ukraine, Radio Free Europe (18 February 2017)

- Russia accepts passports issued by east Ukraine rebels, BBC News (19 February 2017)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lugansk People's Republic. |