Luis Fajardo (Spanish Navy officer)

Luis Fajardo y Ruíz de Avendaño,[1] KOC (c. 1556[2] – 21 May 1617[3]), known simply as Luis Fajardo,[2] was a Spanish admiral and nobleman who had an outstanding naval career in the Spanish Navy. He is considered one of the most reputable Spanish militaries of the last years of the reign of Philip II and the reign of Philip III.[2] He held important positions in the navy and carried out several military operations in which he had to fight against English, Dutch, French and Barbary in the Atlantic, the Caribbean and the Mediterranean. It is known for the conquest of La Mamora in 1614.

Luis Fajardo | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1556 Murcia, Spain |

| Died | 21 May 1617 Madrid, Spain |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Spanish Navy |

| Rank | Captain General |

| Commands held | Navy of the Tierra Firme Navy of the Guard Navy of the Ocean Sea |

| Battles/wars | |

Because he belonged to a noble family, he had several appointments such as Adelantado de Murcia, Knight of the Order of Calatrava and Commander of Almuradiel.[3]

Family

He was the illegitimate son of Luis Fajardo y de la Cueva, 2nd Marquis of Los Vélez, Grandee of Spain and 1st Marquis de Molina. His mother was Ana Ruiz de Avendaño y Alarcón, a neighbor of Vélez-Blanco and a native of Villapalacios, in La Mancha.[2]

Due to his illegitimate status, he initially did not have the same social status as the other children his father had previously had with his only deceased wife, Leonor Fernández de Córdoba.[2] But later he managed to ascend socially, due to the military prestige he obtained during his naval career and the support of his influential paternal family, the House of Los Vélez.[4] On the maternal side, Luis was the only son and heir of his mother.[4]

Later he achieved the recognition of his father, for the good relationship he had with him and the rest of his paternal family.[5] This allowed him to have marital ties with a noble woman.[6] He married Luisa de Tenza, Lady of Espinardo, with whom he had three children. The marriage ties of his descendants, which he managed, also reinforced his social position, as well as that of his children, gaining large possessions for his family in Murcia.[7]

His eldest son was Alonso Fajardo de Tenza, who became governor and captain general of the Philippines in 1616.[8] His second son was Juan Fajardo de Tenza, who accompanied his father in some military operations and also became an admiral, and was governor of Galicia.[9] He also had a daughter named Mencía Fajardo de Tenza, who in 1609 married Juan Antonio Usodemar Narváez, lord of the village of Alcantarilla, a fact that initially did not please her father.[10] In addition to the three children he had with Luisa, he had an illegitimate son named Luis with a single woman. Little is known about this son, except that he accompanied his brother Alonso to the Philippines.[8]

Early life

Luis Fajardo was born around 1556 in Murcia, twenty-three years after the death of his father's only wife, Leonor.[2] From a very young age he entered the military career, accompanying his father along with his brother Diego to suppress the Alpujarras Revolt (1568–1571). At the beginning of 1569 he was the standard-bearer of the army led by his father, and in June of that year he was commissioned to defend Oria and Cantoria from the Moorish attack on the marquesado.[11]

Naval career

In 1593, Fajardo was under the command of Francisco Coloma, captain general of the Tierra Firme Navy (“Armada de Tierra Firme”), participating in the transshipment of the silver left in the Azores Islands for Luis Alfonso de Flores, with his fleet of 12 ships. The following year he was an overseer of the Tierra Fime Navy and then succeeded Coloma in office.[3]

In 1597, he carried out an inspection in Cádiz together with the lawyer Diego Armenteros, due to the Anglo-Dutch sacking of that port the previous year.[12] He was also appointed by the king to preside over the process against those responsible for this disaster.[3]

In 1598, Fajardo was appointed captain general of the Guard Navy (“Armada de la Guardia de la Flota de Indias”),[3] charged with bringing and protecting the Spanish treasure fleet from privateers on their way to Spain, a dangerous and vital job for the Spanish Empire. This will be his main mission until his death and for which he will obtain several honors from the king.[13]

In 1600, Fajardo sent a report to the king, stating the convenience of having galleys in Cartagena de Indias for any eventuality.[3] Between 1601 and 1602, in his work to protect the Spanish treasure fleet, he had some battles against English fleet and even a combined Anglo-Dutch fleet, managing to successfully repel all these adversaries when they attacked him. In the battle against the combined fleet, which was 20 ships, superior to Fajardo's fleet of 7 ships, he managed to damage the flagship and capture the vice-flagship and a patache, at the cost of 200 casualties between killed and wounded.[14] In one of these battles, the English commanders Richard Leveson and Wiliam Monson had joined forces to attack him, but were unsuccessful in their attempt.[3]

In November 1604, he was appointed captain general of the Ocean Sea Navy (“Armada del Mar Océano”), replacing the late Admiral Alonso de Bazán.[15] With this naval force he had the mission of protecting the Iberian coast of the Atlantic and the Strait of Gibraltar, also taking into account that it was the route of arrival of the Spanish treasure fleet. This led him to engagement the fleets of Dutch, English or French privateers on several occasions, even on the coasts of America.[upper-alpha 1]

In 1605, Fajardo carried out with his fleet a punitive expedition to the Caribbean, more precisely in Araya, on the coasts of Cumaná and the Margarita Island. In that place, he attacked by surprise a fleet of Dutch smugglers and privateers who were blocking the area and engaged in the illegal extraction of salt, destroying it completely.[16][17] This fact affected the Dutch industry, which depended on the product for various uses. After the attack, he spent a brief time in the Caribbean chasing privateers before returning to Spain. The following year, he defeated the fleet of Dutch Admiral Willem Haultain at the Battle of Cape San Vicente, having done so with a makeshift fleet.[18] This allowed lifting the blockade of the Spanish-Portuguese coast and the arrival of the Spanish treasure fleet that year.[19]

In 1607, his son Juan began to help him in the leadership of the Ocean Sea Navy.[15] With the Pax Hispanica, Fajardo was frequently in the Spanish Levante,[20] dedicating himself to dealing with the growing threat of Anglo-Barbary piracy in the Mediterranean, trying to hunt down renowned pirates such as Zymen Danseker and Jack Ward.[21]

In May 1609 he gave a report to the king about the problems in the duration of the Spanish ships due to the defective cure. In June of that year, Fajardo commanded an expedition to the Barbary coast, to pursue the pirate Danseker. He arrived at the Tunisian coast, where he attacked the fortified anchorage of La Goulette, destroying and capturing all the ships in the place,[22] which made clear the Spanish capacity to face the pirates. Then he collaborated with part of the fleet in the expulsion of the Moorish from Spain.[3]

In 1612, some 4 galleys of Fajardo's fleet captured the French privateer Jehan Philippe de Castelane's ship, which was carrying the entire collection of manuscripts from the Zaydani Library, belonging to the Moroccan Sultan Muley Zidan.[23] The manuscripts were not returned by the Spanish Crown and became part of the Royal Library of El Escorial.[24]

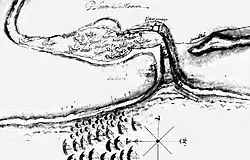

In August 1614, Fajardo commanded an expedition of almost 100 ships with 5,000 landing soldiers, with whom he conquered La Mamora, a military action that earned him great prestige for the measures he took during the attack, and for which he had no casualties.[25] The conquest of the place deprived Muley Zidan of a haven for pirates and prevented this strategic place from falling into Dutch hands.[20][upper-alpha 2]

During the last years of his life he continued to serve in the Ocean Sea Navy and had some naval engagements along the Spanish Atlantic coast. Fajardo died on 21 May 1617, being succeeded by Don Fadrique de Toledo, 1st Marquess of Valdueza, in the command of the Ocean Sea Navy.[3]

Notes

- At the beginning of the 17th century, the Ottoman front in the Mediterranean Sea was no longer the first threat to the Spanish Empire. Now it was the Dutch, French and English navies that were the biggest problem in the Atlantic Ocean.[15]

- At that time, the Dutch were negotiating with Muley Zidan the cession of La Mamora, in order to have a naval station near the Strait of Gibraltar.[26]

References

- Hernández Franco, Juan; Rodríguez Pérez, Raimundo A. (2014). "El linaje se transforma en casas: de los Fajardo a los marqueses de los Vélez y de Espinardo" (in Spanish). 74 (247). España: Revista Hispania: 398. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rodríguez Pérez & Hernández Franco 2013, p. 40.

- "Luis Fajardo", Diccionario Biográfico Español.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 190.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 190–191.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 191.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 203.

- Rodríguez Pérez & Hernández Franco 2013, p. 43.

- Rodríguez Pérez & Hernández Franco 2013, p. 42.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 202.

- Rodríguez Pérez & Hernández Franco 2013, p. 41.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 192.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 192–193.

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 215.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 193.

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 257.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. Santa Barbara, USA: ABC-CLIO. p. 150–151. ISBN 978-1-59884-100-8.

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 232.

- Lothrop Motley, John (2011) [1867]. History of the United Netherlands: From the Death of William the Silent to the Twelve Years' Truce - 1609. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 274–275. ISBN 978-1-108-03665-8.

- Rodríguez Pérez 2010, p. 194.

- Velasco Hernández, Francisco (2012). "Corsarios y piratas ingleses y holandeses en el Sureste español durante el reinado de Felipe III (1598-1621)" (in Spanish) (32). Valladolid, España: Investigaciones históricas: Época moderna y contemporánea, Universidad de Valladolid: 98–101. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fernández Duro 1896, p. 324.

- Hershenzon, Daniel (2014). "Traveling Libraries: The Arabic Manuscriptsof Muley Zidan and the Escorial Library". 18 (6). Journal of Early Modern History: 541–542. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pérez-Bustamante, Ciriaco (1996). La España de Felipe III (in Spanish). Madrid, España: Espasa-Calpe. p. 408.

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 331–332.

- Fernández Duro 1896, p. 331.

Bibliography

- Rodríguez Pérez, Raimundo A.; Hernández Franco, Juan (2013). "Marinos, caballeros y monjas. Los bastardos de la Casa de los Vélez, siglos XVI y XVII". Revista velezana (in Spanish). España (31): 38–47.

- Rodríguez Pérez, Raimundo A. (2010). Un linaje aristocrático en la España de los Habsburgo: los Marqueses de los Vélez (1477-1597) (in Spanish). Murcia, España: Universidad de Murcia.

- "Luis Fajardo". Diccionario Biográfico Español (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. 11 September 2020.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1896). Armada Española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y Aragón (in Spanish). III. Madrid, España: Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval.