Riverside and Avondale

Riverside and Avondale are two adjacent and closely associated neighborhoods, alternatively considered one continuous neighborhood, of Jacksonville, Florida. The area is primarily residential, but includes some commercial districts, including Five Points, the King Street District, and the Shoppes of Avondale.

Riverside and Avondale | |

|---|---|

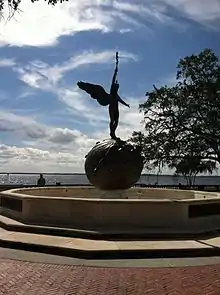

Sculpture by C. Adrian Pillars in Memorial Park | |

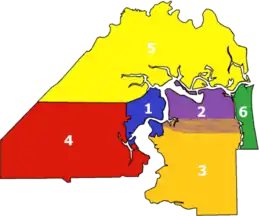

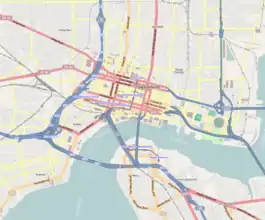

Riverside and Avondale Location within Central Jacksonville | |

| Coordinates: 30°18′53.5″N 81°41′24.3″W | |

| Government | |

| • City Council | Randy DeFoor |

| • U.S. House | Al Lawson (D) |

| ZIP Code | 32204, 32205 |

| Area code(s) | 904 |

Riverside was first platted in 1868 and was annexed by Jacksonville in 1887. Its greatest growth occurred between the Great Fire of 1901 and the failure of the 1920s Florida land boom; this period included the creation of the original Avondale development in 1920. Today, Riverside and Avondale are notable for their particularly diverse architecture and their emphasis on planning and historic preservation, which have made them Florida's most architecturally varied neighborhood. Both neighborhoods are listed as National Register Historic Districts.

Geography

Riverside and Avondale are located to the southwest of Downtown Jacksonville along the St. Johns River. The neighborhood's boundaries are roughly Interstate 10 to the north, the St. Johns River to the east, Fishweir Creek to the south, and Roosevelt Boulevard and the CSX Railroad line to the west.[1] It borders the Brooklyn and North Riverside neighborhoods to the north, Murray Hill to the west, and Lake Shore and Fairfax to the south. The boundary between Riverside and Avondale is not clear cut, even for those living in the neighborhood.[2] It is sometimes given as Seminole Road and Belvedere Avenue, the northern limit of the Avondale Historic District.[3] Alternately, author Wayne Wood of the Jacksonville Historic Landmarks Commission puts it at about McDuff Avenue.[4]

History

Riverside

Riverside and Avondale were developed out of former plantation land. Most of this area was part of two plantations: Dell's Bluff, granted by the Spanish Florida government in 1801, and a tract eventually known as Magnolia Plantation, granted in 1815. Both changed hands several times before the American Civil War.[5] In 1868, Dell's Bluff's then owner, Miles Price, sold off the southern part of the plantation to Florida Union editor Edward M. Cheney and Boston developer John Murray Forbes, who platted the original Riverside development. The northern part Price developed himself as Jacksonville's Brooklyn neighborhood.[6]

Riverside and Brooklyn saw modest growth until 1887, when the city of Jacksonville annexed them and established a streetcar line. Following the Great Fire of 1901, which destroyed most of Downtown Jacksonville, many displaced residents moved to Riverside. Wealthy citizens built mansions close to the river, while the less well-to-do purchased more modest bungalows and other homes further inland. The neighborhood grew steadily, with development continuing well beyond its original bounds to the south, until the collapse of the Florida land boom in the late 1920s. During this period, so many architects working in such a wide variety of contemporary styles experimented in Riverside that it has become the most architecturally diverse neighborhood in Florida.[5] Largely due to Riverside's profusion of bungalow homes, Jacksonville has what is likely the largest number of such structures in the state.[7]

One notable section of Riverside is Silvertown, a subdivision developed in 1887 for African Americans. Initially isolated from largely white Riverside to the east, it was eventually absorbed into the growing neighborhood. As such, Silvertown residents became some of the few black homeowners in Riverside through the period of segregation. A few one-story wood-frame houses in the area may date to the original development, including one house owned by a woman and then her daughter from 1887 into the 1980s.[8]

Avondale

Avondale was developed later as a new area of Riverside on former Magnolia Plantation land. In 1884 Northern developers planned and platted a community in this area called "Edgewood", however it did not take off and the land was largely undeveloped; hunters still pursued game there until the 1910s.[9] In 1920 an investment group led by Telfair Stockton purchased Edgewood and surrounding land to develop as an exclusive upscale subdivision. Named for Cincinnati's Avondale neighborhood, home of former Edgewood owner James R. Challen, the development was billed as "Riverside's Residential Ideal", which was "...desirable because the right kind of people have recognized its worth and because the wrong kind of people can find property more to their liking elsewhere."[4]

Avondale was a restricted, whites only development, and the most extensively planned community Jacksonville had ever seen. In contrast to the architectural diversity in the rest of Riverside, Avondale featured more uniform architecture predominantly in the Mediterranean Revival style. Following its success, several adjacent developments sprung up, which eventually became lumped together as part of Avondale.[4]

Later history and preservation

The mid-20th century brought change to Riverside and Avondale, including the construction of Interstate 95 and the Fuller Warren Bridge, the establishment of St. Vincent's Medical Center, and the construction of office buildings along Riverside Avenue.[10] Through this time, a number of Riverside and Avondale's historic buildings were demolished or allowed to decay. Neighborhood advocates fought this trend by forming a historic preservation organization, Riverside Avondale Preservation, in 1974, and lobbying for the creation of historic districts in the neighborhood.[11]

As a result, the Riverside Historic District, Jacksonville's first historic district, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985; it now comprises 6870 acres and contains 2120 historic buildings.[3][12] In 1989, the Avondale Historic District was added, and the following year the Jacksonville City Council established the Jacksonville Historic Preservation Commission in order to protect historic structures.[11] Riverside Avondale Preservation has grown into one of the largest such organizations in the country. As a result of this focus on preservation and planning, the American Planning Association named Riverside and Avondale one of the country's top ten neighborhoods in 2010.[13]

Commercial districts

Riverside and Avondale are chiefly residential, but they have some commercial zoning, including several commercial centers that are architecturally integrated with the rest of the neighborhood.[4]

Five Points

Five Points is a small commercial district centered on the five-way intersection between Park, Lomax, and Margaret Streets. The area was originally residential, but transitioned to commercial uses after World War I and several retail buildings were constructed. The Park Arcade Building, an Italian Renaissance revival structure with storefronts marked by variant rooflines, set the architectural tone for the district when it was completed in 1928. Other notable features include Sun-Ray Cinema, formerly Riverside Theater, which opened in 1927 as the first movie theater in Florida equipped to show talking pictures.[14] Over the last several decades, Five Points has become known for its edgy, bohemian character and many independent shops, restaurants and businesses.[15] The area has also become a cultural center for Jacksonville's LGBTQ population, being home to various LGBTQ organizations, bars, clubs, and venues as well as the annual River City Pride parade which draws thousands to the district every October.[16]

King Street District

The King Street District originated with Whiteway Corner, a group of commercial buildings at the intersection of King and Park Street built by the Nasrallah brothers beginning in 1927. The Nasrallahs' buildings included the novelty of electric exterior lights, hence the name "White Way".[17] Other notable buildings at this corner are a 1942 Style Moderne structure built for Lane Drug Company by Marsh & Saxelbye, and the 1925 Riverside Baptist Church, designed by prominent architect Addison Mizner.[18]

Subsequently, commercial development and zoning spread along King Street and its cross streets. After several decades of decline, King Street has experienced a revival since 2005 following a successful streetscaping project.[17] A popular beer bar that opened that year set the tone for later establishments, many of them craft beer oriented. Subsequently, the district has become the home of many bars, restaurants, stores, and night clubs, as well as an arts district and two craft breweries to the north. As a result of this growth, the King Street District emerged as Jacksonville's beer hub in the 2010s.[19][20]

Shoppes of Avondale

The Shoppes of Avondale is an upscale shopping center comprising about 46 storefronts on St. Johns Avenue. Like Five Points, it dates to the 1920s, when Avondale was first developed. Its small-scale buildings were designed to blend with the residential neighborhood; the most notable is a 1927 edifice designed by Henry J. Klutho in partnership with Fred S. Cates and Albert N. Cole at 3556-3560 St. Johns Avenue.[21] The center was renovated in 2010 under Jacksonville's Town Center Program, which allocated funds for revitalizing neighborhood commercial districts.[22][23]

Features

City parks in Riverside and Avondale include Riverside Park and Memorial Park, which is situated on the river and features a statue of the "winged figure of youth" sculpted by C. Adrian Pillars.[24] The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens is located in Riverside; founded in 1961, it contains one of the world's three most comprehensive collections of Meissen porcelain, large collections of American, European and Japanese art, and two acres of Italian and English gardens listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[25][26][27] The neighborhood is home to Robert E. Lee High School, one of the city's oldest schools still in use,[28] and the Kent Campus of Florida State College at Jacksonville, the institution's oldest campus.[29]

Notes

- Wood 1992, pp. 110, 111–112.

- Carbone, Reiss & Finotti 2010, p. 178.

- Duval County listings at National Register of Historic Places.

- Wood 1992, p. 111.

- Wood 1992, p. 110.

- Wood 1992, pp. 105–107, 110.

- Wood 1992, pp. 146-147.

- Wood 1992, p. 128.

- Wood 1992, pp. 110–111.

- Wood 1992, pp. 111–114.

- "History of RAP". www.riversideavondale.org. Riverside Avondale preservation. 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Wood 1992, p. 114.

- Gibbons, Timothy J. (October 12, 2010). "Riverside-Avondale named one of 10 great neighborhoods in the nation". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- Wood 1992, p. 138.

- Maria Connor (June 17, 2010). "Five Points stays up late on first Fridays". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Lena Pringle (October 7, 2019). "Jacksonville celebrates 41st Pride Festival with Parade". News4Jax. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- Davis, Ennis (May 28, 2008). "A Walk through Park & King". metrojacksonville.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Wood 1992, p. 141.

- Dare, Stephen (February 7, 2013). "Against The Odds: Miracle Successes on King Street". metrojacksonville.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Roger Bull (June 17, 2010). "Riverside's King Street becoming Jacksonville's Beer Central". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Wood 1992, p. 167.

- David Bauerlein (March 3, 2010). "Jacksonville's Town Center program heading to Avondale". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Mary Maraghy (April 22, 2010). "Dust and disturbances kept to a minimum as city contractors improve Avondale shopping district". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Wood 1992, p. 138, 153.

- Carbone, Reiss & Finotti 2010, pp. 82–83.

- Wood 1992, p. 150.

- Wood 2012.

- Wood 1992, p. 133.

- Gentry 1991, pp. 1, 3.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Riverside and Avondale, Jacksonville, Florida. |

- Carbone, Marisa; Sarah W. Reiss; John Finotti (2010). Insiders' Guide to Jacksonville, 3rd Edition. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-5032-0. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- Gentry, Robert B (1991). A College Tells its Story: An Oral History of Florida Community College at Jacksonville, 1963-1991. Florida Community College at Jacksonville. ASIN B004FL0COY.

- Wood, Wayne (1992). Jacksonville's Architectural Heritage. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-0953-7.

- Wood, Wayne (2012). "Riverside-Avondale: The Great American Neighborhood". www.jaxhistory.com. Jacksonville Historical Society. Retrieved February 28, 2013.