Steroid hormone

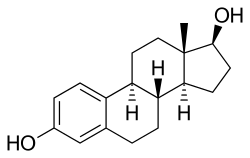

A steroid hormone is a steroid that acts as a hormone. Steroid hormones can be grouped into two classes: corticosteroids (typically made in the adrenal cortex, hence cortico-) and sex steroids (typically made in the gonads or placenta). Within those two classes are five types according to the receptors to which they bind: glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids (both corticosteroids) and androgens, estrogens, and progestogens (sex steroids). Vitamin D derivatives are a sixth closely related hormone system with homologous receptors. They have some of the characteristics of true steroids as receptor ligands.

| Steroid hormone | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Adrenal steroid; Gonadal steroid |

| Use | Various |

| Biological target | Steroid hormone receptors |

| Chemical class | Steroidal; Nonsteroidal |

| In Wikidata | |

Steroid hormones help control metabolism, inflammation, immune functions, salt and water balance, development of sexual characteristics, and the ability to withstand illness and injury. The term steroid describes both hormones produced by the body and artificially produced medications that duplicate the action for the naturally occurring steroids.[1][2][3]

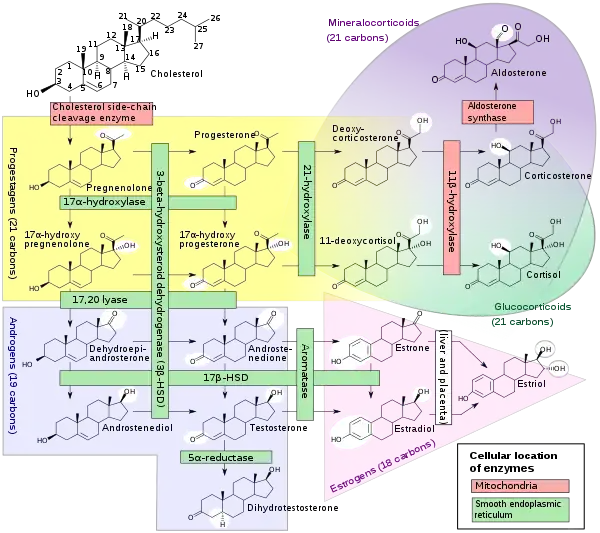

Synthesis

The natural steroid hormones are generally synthesized from cholesterol in the gonads and adrenal glands. These forms of hormones are lipids. They can pass through the cell membrane as they are fat-soluble,[5] and then bind to steroid hormone receptors (which may be nuclear or cytosolic depending on the steroid hormone) to bring about changes within the cell. Steroid hormones are generally carried in the blood, bound to specific carrier proteins such as sex hormone-binding globulin or corticosteroid-binding globulin. Further conversions and catabolism occurs in the liver, in other "peripheral" tissues, and in the target tissues.

| Sex | Sex hormone | Reproductive phase |

Blood production rate |

Gonadal secretion rate |

Metabolic clearance rate |

Reference range (serum levels) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI units | Non-SI units | ||||||

| Men | Androstenedione | – |

2.8 mg/day | 1.6 mg/day | 2200 L/day | 2.8–7.3 nmol/L | 80–210 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | – |

6.5 mg/day | 6.2 mg/day | 950 L/day | 6.9–34.7 nmol/L | 200–1000 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | – |

150 μg/day | 110 μg/day | 2050 L/day | 37–250 pmol/L | 10–70 pg/mL | |

| Estradiol | – |

60 μg/day | 50 μg/day | 1600 L/day | <37–210 pmol/L | 10–57 pg/mL | |

| Estrone sulfate | – |

80 μg/day | Insignificant | 167 L/day | 600–2500 pmol/L | 200–900 pg/mL | |

| Women | Androstenedione | – |

3.2 mg/day | 2.8 mg/day | 2000 L/day | 3.1–12.2 nmol/L | 89–350 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | – |

190 μg/day | 60 μg/day | 500 L/day | 0.7–2.8 nmol/L | 20–81 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | Follicular phase | 110 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 110–400 pmol/L | 30–110 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 260 μg/day | 150 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 310–660 pmol/L | 80–180 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 40 μg/day | Insignificant | 1610 L/day | 22–230 pmol/L | 6–60 pg/mL | ||

| Estradiol | Follicular phase | 90 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 1200 L/day | <37–360 pmol/L | 10–98 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 250 μg/day | 240 μg/day | 1200 L/day | 699–1250 pmol/L | 190–341 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 6 μg/day | Insignificant | 910 L/day | <37–140 pmol/L | 10–38 pg/mL | ||

| Estrone sulfate | Follicular phase | 100 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 700–3600 pmol/L | 250–1300 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 180 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 1100–7300 pmol/L | 400–2600 pg/mL | ||

| Progesterone | Follicular phase | 2 mg/day | 1.7 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 0.3–3 nmol/L | 0.1–0.9 ng/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 25 mg/day | 24 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 19–45 nmol/L | 6–14 ng/mL | ||

Notes and sources

Notes: "The concentration of a steroid in the circulation is determined by the rate at which it is secreted from glands, the rate of metabolism of precursor or prehormones into the steroid, and the rate at which it is extracted by tissues and metabolized. The secretion rate of a steroid refers to the total secretion of the compound from a gland per unit time. Secretion rates have been assessed by sampling the venous effluent from a gland over time and subtracting out the arterial and peripheral venous hormone concentration. The metabolic clearance rate of a steroid is defined as the volume of blood that has been completely cleared of the hormone per unit time. The production rate of a steroid hormone refers to entry into the blood of the compound from all possible sources, including secretion from glands and conversion of prohormones into the steroid of interest. At steady state, the amount of hormone entering the blood from all sources will be equal to the rate at which it is being cleared (metabolic clearance rate) multiplied by blood concentration (production rate = metabolic clearance rate × concentration). If there is little contribution of prohormone metabolism to the circulating pool of steroid, then the production rate will approximate the secretion rate." Sources: See template. | |||||||

Synthetic steroids and sterols

A variety of synthetic steroids and sterols have also been contrived. Most are steroids, but some nonsteroidal molecules can interact with the steroid receptors because of a similarity of shape. Some synthetic steroids are weaker or stronger than the natural steroids whose receptors they activate.[6]

Some examples of synthetic steroid hormones:

- Glucocorticoids: alclometasone, prednisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, cortisone

- Mineralocorticoid: fludrocortisone

- Vitamin D: dihydrotachysterol

- Androgens: oxandrolone, oxabolone, testosterone, nandrolone (also known as anabolic–androgenic steroids or simply anabolic steroids)

- Oestrogens: diethylstilbestrol (DES) and ethinyl estradiol (EE)

- Progestins: norethisterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, hydroxyprogesterone caproate.

Some steroid antagonists:

- Androgen: cyproterone acetate

- Progestins: mifepristone, gestrinone

Transport

Steroid hormones are transported through the blood by being bound to carrier proteins—serum proteins that bind them and increase the hormones' solubility in water. Some examples are sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), corticosteroid-binding globulin, and albumin.[7] Most studies say that hormones can only affect cells when they are not bound by serum proteins. In order to be active, steroid hormones must free themselves from their blood-solubilizing proteins and either bind to extracellular receptors, or passively cross the cell membrane and bind to nuclear receptors. This idea is known as the free hormone hypothesis. This idea is shown in Figure 1 to the right.

One study has found that these steroid-carrier complexes are bound by megalin, a membrane receptor, and are then taken into cells via endocytosis. One possible pathway is that once inside the cell these complexes are taken to the lysosome, where the carrier protein is degraded and the steroid hormone is released into the cytoplasm of the target cell. The hormone then follows a genomic pathway of action. This process is shown in Figure 2 to the right.[8] The role of endocytosis in steroid hormone transport is not well understood and is under further investigation.

In order for steroid hormones to cross the lipid bilayer of cells, they must overcome energetic barriers that would prevent their entering or exiting the membrane. Gibbs free energy is an important concept here. These hormones, which are all derived from cholesterol, have hydrophilic functional groups at either end and hydrophobic carbon backbones. When steroid hormones are entering membranes free energy barriers exist when the functional groups are entering the hydrophobic interior of membrane, but it is energetically favorable for the hydrophobic core of these hormones to enter lipid bilayers. These energy barriers and wells are reversed for hormones exiting membranes. Steroid hormones easily enter and exit the membrane at physiologic conditions. They have been shown experimentally to cross membranes near a rate of 20 μm/s, depending on the hormone.[9]

Though it is energetically more favorable for hormones to be in the membrane than in the ECF or ICF, they do in fact leave the membrane once they have entered it. This is an important consideration because cholesterol—the precursor to all steroid hormones—does not leave the membrane once it has embedded itself inside. The difference between cholesterol and these hormones is that cholesterol is in a much larger negative Gibb's free energy well once inside the membrane, as compared to these hormones. This is because the aliphatic tail on cholesterol has a very favorable interaction with the interior of lipid bilayers.[9]

Mechanisms of action and effects

There are many different mechanisms through which steroid hormones affect their target cells. All of these different pathways can be classified as having either a genomic effect or a non-genomic effect. Genomic pathways are slow and result in altering transcription levels of certain proteins in the cell; non-genomic pathways are much faster.

Genomic pathways

The first identified mechanisms of steroid hormone action were the genomic effects.[10] In this pathway, the free hormones first pass through the cell membrane because they are fat soluble.[5] In the cytoplasm, the steroid may or may not undergo an enzyme-mediated alteration such as reduction, hydroxylation, or aromatization. Then the steroid binds to a specific steroid hormone receptor, also known as a nuclear receptor, which is a large metalloprotein. Upon steroid binding, many kinds of steroid receptors dimerize: two receptor subunits join together to form one functional DNA-binding unit that can enter the cell nucleus. Once in the nucleus, the steroid-receptor ligand complex binds to specific DNA sequences and induces transcription of its target genes.[2][11][12][10]

Non-genomic pathways

Because non-genomic pathways include any mechanism that is not a genomic effect, there are various non-genomic pathways. However, all of these pathways are mediated by some type of steroid hormone receptor found at the plasma membrane.[13] Ion channels, transporters, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), and membrane fluidity have all been shown to be affected by steroid hormones.[9] Of these, GPCR linked proteins are the most common. For more information on these proteins and pathways, visit the steroid hormone receptor page.

References

- Funder JW, Krozowski Z, Myles K, Sato A, Sheppard KE, Young M (1997). "Mineralocorticoid receptors, salt, and hypertension". Recent Prog Horm Res. 52: 247–260. PMID 9238855.

- Gupta BBP, Lalchhandama K (2002). "Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid action" (PDF). Current Science. 83 (9): 1103–1111.

- Frye CA (2009). "Steroids, reproductive endocrine function, and affect. A review". Minerva Ginecol. 61 (6): 541–562. PMID 19942840.

- Häggström, Mikael; Richfield, David (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005. ISSN 2002-4436.

- Linda J. Heffner; Danny J. Schust (2010). The Reproductive System at a Glance. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-4051-9452-5. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- Nahar L, Sarker SD, Turner AB (2007). "A review on synthetic and natural steroid dimers: 1997-2006". Curr Med Chem. 14 (12): 1349–1370. doi:10.2174/092986707780597880. PMID 17504217.

- Adams JS (2005). ""Bound" to work: The free hormone hypothesis revisited". Cell. 122 (5): 647–9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.024. PMID 16143095.

- Hammes A (2005). "Role of endocytosis in cellular uptake of sex steroids". Cell. 122 (5): 751–62. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.032.

- Oren I (2004). "Free diffusion of steroid hormones across biomembranes: A simplex search with implicit solvent model calculations". Biophysical Journal. 87 (2): 768–79. doi:10.1529/biophysj.103.035527. PMC 1304487.

- Rousseau G (2013). "Fifty years ago: The quest for steroid hormone receptors". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 375 (1–2): 10–3. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2013.05.005. PMID 23684885.

- Moore FL, Evans SJ (1995). "Steroid hormones use non-genomic mechanisms to control brain functions and behaviors: a review of evidence". Brain Behav Evol. 54 (4): 41–50. doi:10.1159/000006610. PMID 10516403.

- Marcinkowska E, Wiedłocha A (2002). "Steroid signal transduction activated at the cell membrane: from plants to animals". Acta Biochim Pol. 49 (9): 735–745. PMID 12422243.

- Wang C, Liu Y, Cao JM (2014). "G protein-coupled receptors: Extranuclear mediators for the non-genomic actions of steroids". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 15 (9): 15412–25. doi:10.3390/ijms150915412. PMC 4200746. PMID 25257522.

Further reading

- Brook CG (1999). "Mechanism of puberty". Horm. Res. 51 Suppl 3 (3): 52–4. doi:10.1159/000053162. PMID 10592444.

- Holmes SJ, Shalet SM (1996). "Role of growth hormone and sex steroids in achieving and maintaining normal bone mass". Horm. Res. 45 (1–2): 86–93. doi:10.1159/000184765. PMID 8742125.

- Ottolenghi C, Uda M, Crisponi L, Omari S, Cao A, Forabosco A, Schlessinger D (Jan 2007). "Determination and stability of sex". BioEssays. 29 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1002/bies.20515. PMID 17187356.

- Couse JF, Korach KS (June 1998). "Exploring the role of sex steroids through studies of receptor deficient mice". J. Mol. Med. 76 (7): 497–511. doi:10.1007/s001090050244. PMID 9660168.

- McEwen BS (1992). "Steroid hormones: effect on brain development and function". Horm. Res. 37 Suppl 3 (3): 1–10. doi:10.1159/000182393. PMID 1330863.

- Simons (Aug 2008). "physiological versus pharmacological steroid hormone actions". BioEssays. 30 (8): 744–56. doi:10.1002/bies.20792. PMC 2742386. PMID 18623071.

- Han, Thang S.; Walker, Brian R.; Arlt, Wiebke; Ross, Richard J. (17 December 2013). "Treatment and health outcomes in adults with congenital adrenal hyperplasia". Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 10 (2): 115–124. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2013.239. PMID 24342885Figure 2: The adrenal steroidogenesis pathway.

External links

- An animated and narrated tutorial about nuclear receptor signaling

- Virtual Chembook

- stedwards.edu

- How Steroid Hormones Work