Sultanate of Mogadishu

The Sultanate of Mogadishu (Somali: Saldanadda Muqdisho, Arabic: سلطنة مقديشو) (fl.9th- 13th centuries[1]), also known as the Kingdom of Magadazo,[1] was a medieval Somali sultanate centered in southern Somalia. It rose as one of the pre-eminent powers in the Horn of Africa under the rule of Fakhr ad-Din before becoming part of the expanding Ajuran Empire in the 13th century.[2] The Mogadishu Sultanate maintained a vast trading network, dominated the regional gold trade, minted its own currency, and left an extensive architectural legacy in present-day southern Somalia.[3]

Sultanate of Mogadishu Saldanadda Muqdisho سلطنة مقديشو | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th century–13th century | |||||||

The "City of Mogadishu" on Fra Mauro's medieval map. | |||||||

| Capital | Mogadishu | ||||||

| Common languages | Somali, Arabic | ||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||

| Sultan | |||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||

• Established | 9th century | ||||||

• Disestablished | 13th century | ||||||

| Currency | Mogadishan | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | |||||||

Ethnicity

The ethnic origins of the founders of Mogadishu and its subsequent sultanate has been the subject of much debate in Somali Studies. I.M Lewis postulates that the city was founded and ruled by a council of Arab and Persian families.[4][5] It has now been widely accepted that there were already existing communities on the Somali coast with local African leadership, to whom the Arab and Persian families had to ask for permission to settle in their cities.[6] Ibn Battuta also stated that the natives of Mogadishu were dark-skinned.[7]

This is corroborated by the 1st century AD Greek document the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, detailing multiple prosperous port cities in ancient Somalia, as well as the identification of ancient Sarapion with the city that would later be known as Mogadishu.[8] When Ibn Battuta visited the Sultanate in the 14th century, he identified the Sultan as being of Barbara origin,[9] an ancient term to describe the ancestors of the Somali people. According to Ross E. Dunn neither Mogadishu, or any other city on the coast could be considered alien enclaves of Arabs or Persians, but were in-fact African towns.[10]

History

Mogadishu Sultanate

For many years Mogadishu functioned as the pre-eminent city in the بلد البربر (Bilad al Barbar - "Land of the Berbers"), as medieval Arabic-speakers named the Somali coast.[11][12][13][14] Following his visit to the city, the 12th-century Syrian historian Yaqut al-Hamawi (a former slave of Greek origin) wrote a global history of many places he visited Mogadishu and called it the richest and most powerful city in the region and was an Islamic center across the Indian Ocean.[15][16]

Archaeological excavations have recovered many coins from China, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. The majority of the Chinese coins date to the Song Dynasty, although the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty "are also represented,"[17] according to Richard Pankhurst.

Ajuran Sultanate

In the early 13th century, Mogadishu along with other coastal and interior Somali cities in southern Somalia and eastern Abyissina came under the Ajuran Sultanate control and experienced another Golden Age.[18] By the 1500s, Mogadishu was no longer a vassal state and became a full fledged Ajuran city. An Ajuran family, Muduffar, established a dynasty in the city, thus combining two entities together for the next 350 years, the fortunes of the urban cities in the interior and coast became the fortunes of the other.[19]

During his travels, Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi (1213–1286) noted that Mogadishu city had already become the leading Islamic center in the region.[20] By the time of the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta's appearance on the Somali coast in 1331, the city was at the zenith of its prosperity. He described Mogadishu as "an exceedingly large city" with many rich merchants, which was famous for its high quality fabric that it exported to Egypt, among other places.[21][22] He also describes the hospitality of the people of Mogadishu and how locals would put travelers up in their home to help the local economy.[23] Battuta added that the city was ruled by a Somali Sultan, Abu Bakr ibn Shaikh 'Umar,[24][25] who had a Barbara origin, an ancient term to describe the ancestors of the Somali people. and spoke the Mogadishan Somali or Banadiri Somali (referred to by Battuta as Benadir) and Arabic with equal fluency.[25][26] The Sultan also had a retinue of wazirs (ministers), legal experts, commanders, royal eunuchs, and other officials at his beck and call.[25] Ibn Khaldun (1332 to 1406) noted in his book that Mogadishu was a massive metropolis. He also claimed that the city was a very populous with many wealthy merchants.[27]

This period gave birth to notable figures like Abd al-Aziz of Mogadishu who was described as the governor and island chief of Maldives by Ibn Battuta[28][29][30] After him is named the Abdul-Aziz Mosque in Mogadishu which has remained there for centuries.[31]

Duarte Barbosa, the famous Portuguese traveler wrote about Mogadishu (c 1517-1518):[32]

It has a king over it, and is a place of great trade in merchandise. Ships come there from the kingdom of Cambay (India) and from Aden with stuffs of all kinds, and with spices. And they carry away from there much gold, ivory, beeswax, and other things upon which they make a profit. In this town there is plenty of meat, wheat, barley, and horses, and much fruit: it is a very rich place.

The Sultanate of Mogadishu sent ambassadors to China to establish diplomatic ties, creating the first ever recorded African community in China and the most notable was Sa'id of Mogadishu who was the first African man to set foot in China. In return, Emperor Yongle, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), dispatched one of the largest fleets in history to trade with Sultanate. The fleet, under the leadership of the famed Hui Muslim Zheng He, arrived at Mogadishu, while the city was at its zenith. Along with gold, frankincense and fabrics, Zheng brought back the first ever African wildlife to China, which included hippos, giraffes and gazelles.[33][34][35][36]

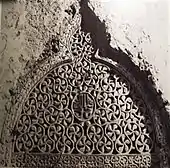

Vasco Da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[37] In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[38] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria),[39] together with Merca and Barawa also served as transit stops for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[40] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz also brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[41]

The Portuguese Empire was unsuccessful of conquering Mogadishu where the powerful naval Portuguese commander called João de Sepúvelda and his army fleets was soundly defeated by the powerful Ajuran navy during the Battle of Benadir.[42]

According to the 16th-century explorer, Leo Africanus indicates that the native inhabitants of the Mogadishu polity were of the same origins as the denizens of the northern people of Zeila the capital of Adal Sultanate. They were generally tall with an olive skin complexion, with some being darker. They would wear traditional rich white silk wrapped around their bodies and have Islamic turbans and coastal people would only wear sarongs, and spoke Arabic as a lingua franca. Their weaponry consisted of traditional Somali weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, battle axe, and bows, although they received assistance from its close ally the Ottoman Empire and with the import of firearms such as muskets and cannons. Most were Muslims, although a few adhered to heathen bedouin tradition; there were also a number of Abyssinian Christians further inland. Mogadishu itself was a wealthy, and well-built city-state, which maintained commercial trade with kingdoms across the world.[43] The metropolis city was surrounded by walled stone fortifications.[44][45]

Trade

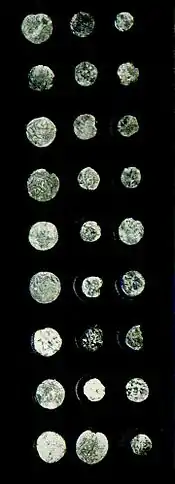

Somali merchants from Mogadishu established a colony in Mozambique to extract gold from the mines in Sofala.[46] During the 9th century, Mogadishu minted its own Mogadishu currency for its medieval trading empire in the Indian Ocean.[47][48] It centralized its commercial hegemony by minting coins to facilitate regional trade. The currency bore the names of the 13 successive Sultans of Mogadishu. The oldest pieces date back to 923-24 and on the front bear the name of Imsail ibn Muhahamad, the then Sultan of Mogadishu.[49] On the back of the coins, the names of the four Caliphs of the Rashidun Caliphate are inscribed.[50] Other coins were also minted in the style of the extant Fatimid and the Ottoman currencies. Mogadishan coins were in widespread circulation. Pieces have been found as far away as modern United Arab Emirates, where a coin bearing the name of a 12th-century Somali Sultan Ali b. Yusuf of Mogadishu was excavated.[47] Bronze pieces belonging to the Sultans of Mogadishu have also been found at Belid near Salalah in Dhofar.[51]

Upon arrival in Mogadishu's harbour, it was custom for small boats to approach the arriving vessel, and their occupants to offer food and hospitality to the merchants on the ship. If a merchant accepted such an offer, then he was obligated to lodge in that person's house and to accept their services as sales agent for whatever business they transacted in Mogadishu. Zheng He, the famous Chinese traveler obtained zebra and lions from Mogadishu and camels and ostriches from Barawa.[52]

Sultans of Mogadishu

| Sultans of Mogadishu | |

|

Abu Bakr b. Fakhr ad Din Ismail b. Muhammad Al-Rahman b. al-Musa'id Yusuf b. Sa'id Sultan Muhammad Rasul b. 'Ali Yusuf b. Abi Bakr Malik b. Sa'id Sultan 'Umar Zubayr b. 'Umar |

The various Sultans of Mogadishu are mainly known from the Mogadishan currency on which many of their names are engraved. A private collection of coins found in Mogadishu revealed a minimum of 23 Sultans.[53] The founder of the Sultanate was reportedly Fakhr ad-Din who was the first Sultan of Mogadishu and founder of the Fakhr ad-Din Dynasty.[54] While only a handful of the pieces have been precisely dated, the Mogadishu Sultanate's first coins were minted at the beginning of the 13th century, with the last issued around the early 17th century. For trade, the Ajuran Sultanate also utilized the Mogadishan currency who became allied to the Muzaffar dynasty of Mogadishu at the end of the 16th century.[48] Mogadishan coins have been found as far away as the present-day country of the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East.[55] The following list of the Sultans of Mogadishu is abridged and is primarily derived from these mints.[56] The first of two dates uses the Islamic calendar, with the second using the Julian calendar; single dates are based on the Julian (European) calendar.

References

- Africanus, Leo (1526). the second kingdome of the land of Aian, situate upon the easterne Ocean, is confined northward by the kingdome of Adel, & westward by the Abassin empire%5b...%5d unto the foresaid kingdome of Adea belongeth the kingdome of Magadazo, so called of the principall citie therein The History and Description of Africa Check

|url=value (help). Hakluyt Society. p. 53. - Abdurahman, Abdillahi (18 September 2017). Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1. 1. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1-909112-79-7.

- Jenkins, Everett (1 July 2000). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500-1799): A Comprehensive Chronolog. Mcfarland. p. 49. ISBN 9781476608891.

- I.M. Lewis, Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar, and Saho, Issue 1, (International African Institute: 1955), p. 47.

- I.M. Lewis, The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1965), p. 37

- Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia edited by Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley Page 252

- https://sites.google.com/site/historyofeastafrica/ibn-battuta-mogadishu

- Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1 - Page 48

- he Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354: Volume II Page 375

- The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century Page 124

- M. Elfasi, Ivan Hrbek "Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century", "General History of Africa". Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama, (Cambridge University Press: 1998), p. 121.

- J. D. Fage, Roland Oliver, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa, (Cambridge University Press: 1977), p. 190.

- George Wynn Brereton Huntingford, Agatharchides, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs "On the Erythraean Sea", (Hakluyt Society: 1980), p. 83.

- Roland Anthony Oliver, J. D. Fage, Journal of African history, Volume 7, (Cambridge University Press.: 1966), p. 30.

- I.M. Lewis, A modern history of Somalia: nation and state in the Horn of Africa, 2nd edition, revised, illustrated, (Westview Press: 1988), p. 20.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1961). An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia. London: Lalibela House. ASIN B000J1GFHC., p. 268

- Lee V. Cassanelli, The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600-1900, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1982), p.102.

- Dumper, Michael (2007). "Mogadishu". Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. US: ABC-CLIO. p. 252.

- P. L. Shinnie, The African Iron Age, (Clarendon Press: 1971), p.135

- Helen Chapin Metz (1992). Somalia: A Country Study. US: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0844407753.

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780330418799.

- Versteegh, Kees (2008). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, Volume 4. Brill. p. 276. ISBN 978-9004144767.

- David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State, (Westview Press: 1987), p. 15.

- Chapurukha Makokha Kusimba, The Rise and Fall of Swahili States, (AltaMira Press: 1999), p.58

- Brett, Michael (1 January 1999). Ibn Khaldun and the Medieval Maghrib. Ashgate/Variorum. ISBN 9780860787723. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- Forbes, Andrew; Bishop, Kevin (2004). The Maldives: Kingdom of a Thousand Isles. Odyssey. ISBN 978-962-217-710-9.

- Bhatt, Purnima Mehta (2017-09-05). The African Diaspora in India: Assimilation, Change and Cultural Survivals. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-37365-4.

- Kenya Past and Present. Kenya Museum Society. 1980.

- The Somali Nation and Abyssinian Colonialism. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Somali Democratic Republic. 1978.

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", Natural History Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rice, Xan (25 July 2010). "Chinese archaeologists' African quest for sunken ship of Ming admiral". The Guardian.

- "Could a rusty coin re-write Chinese-African history?". BBC News. 18 October 2010.

- "Zheng He'S Voyages to the Western Oceans 郑和下西洋". People.chinese.cn. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Da Gama's First Voyage pg.88

- East Africa and its Invaders pg.38

- Alpers, Edward A. (1976). "Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa, c. 1500-1800". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 9 (1): 35. doi:10.2307/217389. JSTOR 217389.

- Harris, Nigel (2003). The Return of Cosmopolitan Capital: Globalization, the State and War. I.B.Tauris. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86064-786-4.

- Barendse, Rene J. (2002). The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-45835-7.

- The Portuguese period in East Africa – Page 112

- Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37857-7.

- (Africanus), Leo (6 April 1969). "A Geographical Historie of Africa". Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- Dunn, Ross E. (1987). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta. Berkeley: University of California. p. 373. ISBN 978-0-520-05771-5., p. 125

- pg 4 - The quest for an African Eldorado: Sofala, By Terry H. Elkiss

- Northeast African Studies, Volume 2. 1995. p. 24.

- Stanley, Bruce (2007). "Mogadishu". In Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (eds.). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- Esposito, Ed (1999). The Oxford History of Islam. p. 502. ISBN 9780195107999.

- The Numismatic Chronicle. 1978. p. 188.

- Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Volume 1. The Seminar. 1970. p. 42. ISBN 0231107145. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- Zheng He's Voyages Down the Western Seas. 五洲传播出版社. 2005. ISBN 978-7-5085-0708-8.

- African Abstracts - Page 160

- Luling, Virginia (2001). Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years. Transaction Publishers. p. 272. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- Chittick, H. Neville (1976). An Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition, 1975. British Institute in Eastern Africa. pp. 117–133.

- Album, Stephen (1993). A Checklist of Popular Islamic Coins. Stephen Album. p. 28. ISBN 0963602403. Retrieved 28 February 2015.