Sultanate of the Geledi

The Sultanate of the Geledi (Somali: Saldanadda Geledi, Arabic: سلطنة غلدي) also known as the Gobroon Dynasty [1] was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the late-17th century and 19th century. The Sultanate was governed by the Gobroon Dynasty. It was established by the Geledi soldier Ibrahim Adeer, who had defeated various vassals of the Ajuran Sultanate and founded the House of Gobroon. The dynasty reached its apex under the successive reigns of Sultan Mahamud Ibrahim who built the Geledi army and successfully repelled the Oromo invasion and Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, who successfully modernized the Geledi economy and consolidated Geledi power during the Conquest of Bardera in 1843,[2] and would go on to force tribute from Said bin Sultan the ruler of the Omani Empire.[3] Geledi Sultans had strong regional ties and built alliances with the Pate and Witu Sultanates on the Swahili coast.[4] Trade and Geledi power would continue to remain strong until the death of the powerful Sultan Ahmed Yusuf in 1878. The sultanate was eventually incorporated into Italian Somaliland in 1908, and ended with the death of Osman Ahmed in 1910.[5]

Sultanate of the Geledi Saldanadda Geledi سلالة غلدي | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| late 17th century–1910 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Afgooye | ||||||||

| Common languages | Somali · Arabic | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Sulṭān Imam Sheikh | |||||||||

• late 17th century–mid 18th century | Ibrahim Adeer | ||||||||

• 1878 – 1910 | Osman Ahmed | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | late 17th century | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1910 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Origins

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somalia |

|

|

At the end of the 17th century, the Ajuran Sultanate was on its decline, and various vassals were now breaking free or being absorbed by new Somali powers. One of these powers was the Silcis Sultanate, which began consolidating its rule over the Afgooye region. Ibrahim Adeer led the revolt against the Silcis ruler Umar Abrone and his oppressive daughter, Princess Fay.[6] After his victory over the Silcis, Ibrahim then proclaimed himself Sultan and subsequently started the Gobroon Dynasty.

Geledi Sultanate was a Rahanweyn Kingdom ruled by the noble Geledi clan which controlled the entire Jubba River and extending parts of Shebelle River and dominating the East African trade. The Geledi Sultanate had enough power to force the southern Arabians to pay tribute to the noble Geledi Rulers like Ahmed Yusuf.[7]

The nobles within the Geledi claim descent from Omar al-Din. He had 3 other brothers, Fakhr and with 2 others of whom their names are given differently as Shams, Umudi, Alahi and Ahmed. Together they were known as Afarta Timid , 'the 4 who came', indicating their origins from Arabia.[8]

Bureaucracy

The Sultanate of Geledi exerted a strong centralized authority during its existence and possessed all of the organs and trappings of an integrated modern state: a functioning bureaucracy, a hereditary nobility, titled aristocrats, a taxing system, conducting foreign policy, a state flag, as well as a professional army.[9][10] The great sultanate also maintained written records of their activities, which still exist.[11]

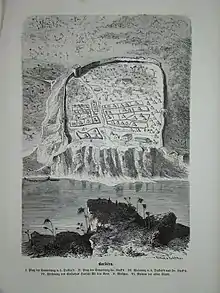

The Geledi Sultanate's main capital was at Afgooye where the rulers resided in the grand palace. The kingdom had a number of castles, forts and other variety of architectures in various areas within its realm, including a fortress at Luuq and a citadel at Bardera.[12]

The Sultanate covered all Digil and Mirifle territories of Somalia. This is what some call the Geledi confederacy. The confederacy was not only confined to Digil and Mirifle but incorporated other Somalis such as Bimaal, Sheekhaal, and Wacdaan. To reign such a diverse Sultanate, the rulers promoted a policy of indirect administration. They allowed the Malaks, Islaws (tribal chiefs), Imams, Sheikhs (religious figures), and Akhiyaars (notable elders) of the community to play significant roles in the administration of the Sultanate. The Geledi rulers were not only the political head of the Sultanate but also were portrayed as religious leaders.[5]

Clear devolution of power was also present with the Geledi Sultan delegating certain regions of the sultanate to be managed by his close relatives, who often wielded significant influence in their own right. Sultan Ahmed Yusuf 's administration was described as such by the British Parliament.

The Somali tribe of Ruhwaina. The Chief of this and other tribes behind Brava, Marka and Mogdisho is Ahmed Yusuf, who resides at Galhed, one day's march or less from the latter town. Two days further inland is Dafert, a large town governed by Aweka Haji, his brother. These are the principal towns of the Ruhwaina. At four, five, and six hours respectively from Marka lie the towns of Golveen (Golweyn), Bulo Mareerta, and Addormo, governed by Abobokur Yusuf, another brother who though nominally under the orders of the first-named chief, levies black-mail on his own account, and negotiates with the governors of Marka and Brava direct. He resides with about 2,000 soldiers principally slaves at Bulo Mareta; the towns of Gulveen which he often vists and Addormo being occupied by somalis growing produce, cattle &c. and doing a large trade with Marka.[13] The brother of Sultan Ahmed Yusuf, Abobokur Yusuf managed the lands opposite the Banadir ports of Brava & Marka and also received a tribute from Brava. This Abobokur Yusuf was accustomed to send messengers to Brava for tribute, and he drew thence about 2,000 dollars per annum.[13]

Economy

The Geledi Sultanate maintained a vast trading network, trading with Arabia, Persia, India, Near East, Europe and the Swahili World, dominating the East African trade, minted its own currency, and were recognized as regional powers.[14]

In the case of the Geledi, wealth accrued to the nobles and to the Sultanate not only from the market cultivation which it had utilized from the Shebelle and Jubba valleys but also trade from their involvement in the slave trade and other enterprises such as ivory, cotton, iron, gold, and among many other commodities. Generally, they also raised livestock animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, and chicken.[15]

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Gobroon dynasty had turned their religious prestige into political power and were recognized as the rulers of an increasingly centralized and wealthy state. As already mentioned, much of their wealth was based on control of fertile riverine lands. Using slave labour obtained through the coastal ports the Geledi gradually shifted their economic base away from its traditional dependency on pastoralism and subsistence agriculture to one built largely on plantation agriculture and production of cash crops such as grain, cotton, maize, sorghum, and a variety of fruits and vegetables, especially bananas, mangos, sugarcane, cotton, tomatoes, squash and much more. It is traversed by historic caravan routes. Trade on the rivers themselves connected with the coast to the interior markets.[16] During this period, the Somali agricultural output to Arabian markets was so great that the coast of South Somalia came to be known as the Grain Coast of Yemen and Oman.[17]

Afgooye, the headquarters of the Sultanate, was an extremely wealthy and large city. Afgooye had some thriving industries such as weaving, shoemaking, tableware, jewellery, pottery and produced other various products. Afgooye was the crossroads of caravans bringing ostrich feathers, leopard skins, and aloe in exchange for foreign fabrics, sugar, dates and firearms.They raised numerous livestock animals for meat, milk and ghee. It is said that every household in Afgooye was wealthy and you could not find a single poor person.The farmers of Afgooye outskirts produced large quantity of fruits and vegetables.[18]

Afgooye merchants boasted their wealth; one of their wealthiest said

Moordiinle iyo mereeyey iyo mooro lidow, maalki jeri keenow kuma moogi malabside. Bring all the wealth of Moordiinle, Mereeyey, and the enclosures of lidow, I scarcely notice it.[18]

Military

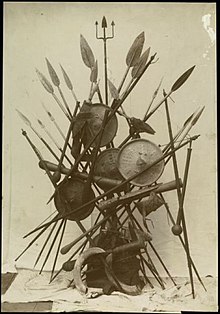

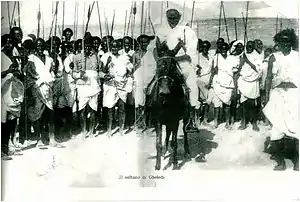

The Geledi army numbered 20,000 men in times of peace, and could be raised to 50,000 troops in times of war.[19] The supreme commanders of the army were the Sultan and his brother, who in turn had Malaakhs and Garads under them. The military was supplied with rifles and cannons by Somali traders of the coastal regions that controlled the East African arms trade.

The best horse breeds were raised in Luuq and later sent to the army after maturity. They would be used for military purposes, and numerous stone fortifications were erected to provide shelter for the army in the interior and coastal districts. In each province, the soldiers were under the supervision of a military commander known as a Malaakh, and the coastal areas and the Indian ocean trade were protected by a navy.[20]

Society

The Geledi society is divided into three castes nobles, commoners, and slaves (to use terms adopted by Helander) Each of these castes consists of several lineage groups, whose federation formed the Geledi state; the lineage are divided between two moieties. Tolweyne and Yebdaale, each living in its section of the city. The nobles, in the old society, were the ruling group but depended on the support of the commoner lineages.[21]

Noblility

The noble caste belonged to rulers. However, all members of the Geledi clan were also considered of noble stock despite the majority of them not being rulers. Nobility was not only exclusive to the Geledi clan as there were rulers of many districts in the Geledi realm that didn't belong to the Geledi lineage.[21]

Commoners

The commoners were typical citizens that mainly consist of non-Geledi Somalis and traditionally consist of urban dwellers, farmers, pastoral nomads as well as officials, merchants, engineers, scholars, soldiers, priests, craftsmen, port workers, and other various professions. The commoners were the majority in the kingdom and were treated as equals.[21]

Slaves

The slaves were mostly of Bantu origin and were used for labour. The men would work as agricultural labourers led by their farmer-owners and some would work in construction led by engineers. They would also be employed into the army and were separated from the rest of the Geledi army and were branched as Mamaluks meaning slave soldiers. The women would work as domestic servants and perform a variety of household services for their owners, from providing, cooking, cleaning, and laundry or taking care of children and elderly dependents, and other household errands. They would also be looked down upon for any kind of sexual contact and were deemed as unattractive.[22]

The Bantus were not exclusive to slavery. Oromos would sometimes be enslaved following raids and wars.[23] However, there were marked differences in terms of the perception, capture, treatment, and duties of the Oromo versus the Bantu slaves. On an individual basis, Oromo subjects were not viewed as racially jareer by their Somali captors.[24] Despite Oromos taking the same roles as the Bantus they were not treated the same. The most fortunate of the men worked as the officials or bodyguards of the ruler and emirs, or as business managers for rich merchants. They enjoyed significant personal freedom and occasionally held slaves of their own.[25] Prized for their beauty and viewed as legitimate sexual partners, many Oromo women became either wives or concubines of their Somali owners, while others became domestic servants. The most beautiful ones often enjoyed a wealthy lifestyle and became mistresses of the elite or even mothers to rulers.[26]

Rulers

Detailed biographies of the Sultanate's rulers

| # | Sultan | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ibrahim Adeer | late 17th century–mid 18th century | Founded the Geledi Sultanate after defeating the Ajuran Sultanate. First ruler in the Gobroon Dynasty.[27] |

| 2 | Mahamud Ibrahim | mid-18th-1828[28] | Inherited throne from father. Militarized the Geledi state and successfully repelled the Oromo invaders and tackled Arab pirates in the indian ocean. |

| 3 | Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim | 1828–1848[28] | Rule marked the start of the golden age of the Geledis. Destroyed the Bardhera Jama'a and revolutionized the Geledi economy. Collected tribute from Said bin Sultan ruler of the Omani Empire[29] |

| 4 | Ahmed Yusuf | 1848–1878[28] | Dominant in East African trade and successfully prevented foreign penetration in Somalia |

| 5 | Osman Ahmed | 1878-1910[28] | Inherited throne from father. Reign marked the end of the Geledi sultanate. Decisively defeated the Abyssinians at the Battle of Luuq and Dervish at the Battle of Xudur. |

Legacy

The Sultanate left a rich legacy and continues to live on in popular memory and poetry composed about the powerful Sultans and other noble figures during the period. One notable poem was recorded by Virginia Luling in 1989 during her visit to Afgooye. Geledi laashins (poets) sang about the ever present issue of land theft by the Somali government. Sultan Subuge was asked to help the community and reminded of his legendary Gobroon forefathers of the centuries prior.[30]

The law then was not this law was performed by the leading laashins of Afgooye, Hiraabey, Muuse Cusmaan and Abukar Cali Goitow alongside a few others, addressed to the current leader Sultan Subuge .[31]

Here the richest selection of the poem performed by Goitow

Ganaane gubow gaala guuriow Gooble maahinoo Geelidle ma goynin |

You who burnt Ganaane and chased away the infidels |

| —Abubakr Cali Goitow The law then was not this law [32] |

See also

- Ajuran Sultanate

- Hiraab Imamate

- History of Somalia

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

Notes

- Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years - Virginia Luling (2002) Page 229

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. xxix. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African History, Volume 2. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 990. ISBN 9781579584542.

- Marguerite, Ylvisaker (1978). "The Origins and Development of the Witu Sultanate". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. Vol. 11 (4): 669–688.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 210. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- Luling (1993), p.13.

- Luling (2002), p.272.

- Luling, Virginia (2002). Somali Sultanate: the Geledi city-state over 150 years. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-874209-98-0.

- Horn of Africa, Volume 15, Issues 1-4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.

- Michigan State University. African Studies Center, Northeast African studies, Volumes 11-12, (Michigan State University Press: 1989), p.32.

- Sub-Saharan Africa Report, Issues 57-67. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 1986. p. 34.

- S. B. Miles, On the Neighbourhood of Bunder Marayah, Vol. 42, (Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the institute of British Geographers): 1872), p.61-63.

- Great Britain, House of Commons (1876). Accounts and Papers volume 70. HM Stationery Office. p. 13.

- Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years - Virginia Luling (2002) Page 155

- Nelson, Harold (1982). "The Society and it's Environment". Somalia, a Country Study. ISBN 9780844407753.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 116. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- East Africa and the Indian Ocean By Edward A. Alpers pg 66

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 28. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- Transactions of the Bombay Geographical Society ..by Bombay Geographical Society pg.392

- Reese, Scott Steven (1996). Patricians of the Benaadir: Islamic learning, commerce and Somali urban identity in the nineteenth century. University of Pennsylvania. p. 179.

- Lewis, I.M (1996). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 9781135751746.

- Henry Louis Gates, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1746

- Bridget Anderson, World Directory of Minorities, (Minority Rights Group International: 1997), p. 456.

- Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 116.

- Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 82.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2004). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0203493021.

- Njoku, Raphael. The History of Somalia. Greenwood. ISBN 9780313378577.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 26. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African History, Volume 2. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 990. ISBN 9781579584542.

- Luling, Virginia (1996). "'The Law Then Was Not This Law': Past and Present in Extemporized Verse at a Southern Somali Festival". African Languages and Cultures. Supplement. No. 3: 213–228.

- Luling, Virginia (1996). "'The Law Then Was Not This Law': Past and Present in Extemporized Verse at a Southern Somali Festival". African Languages and Cultures. Supplement. No. 3: 213–228.

- Luling, Virginia (1996). "'The Law Then Was Not This Law': Past and Present in Extemporized Verse at a Southern Somali Festival". African Languages and Cultures. Supplement. No. 3: 213–228.

References

- Luling, Virginia (2002). Somali Sultanate: the Geledi city-state over 150 years. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0914-1.

- Luling, Virginia (1993). The Use of the Past: Variation in Historical traditions in a South Somalia community. University of Besançon.

Further reading

- Virginia Luling (2002). Somali Sultanate: the Geledi city-state over 150 years. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0914-1.