Abdelaziz of Morocco

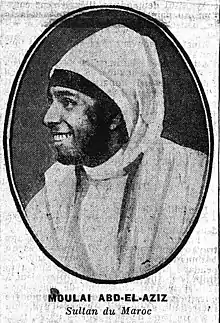

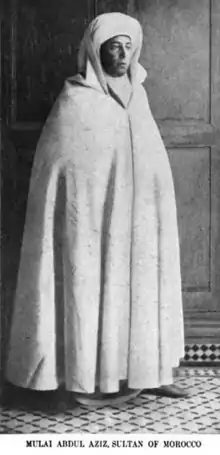

Abdelaziz of Morocco (24 February 1878 – 10 June 1943;[1][2] Arabic: عبد العزيز الرابع), also known as Mulai Abd al-Aziz IV, succeeded his father Hassan I of Morocco as the Sultan of Morocco in 1894 at the age of sixteen. He was a member of the Alaouite dynasty.

| Abdelaziz of Morocco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sultan of Morocco | |

| Reign | 1894–1908 |

| Predecessor | Hassan I |

| Successor | Abdelhafid |

| Born | 24 February 1878 Fes, Morocco |

| Died | 10 June 1943 (aged 65) Tangier, Morocco |

| House | House of Alaoui |

He tried to strengthen the central government by implementing a new tax on agriculture and livestock, a measure which was strongly opposed by sections of the society. This in turn led Abdelaziz to mortgage the customs revenues and to borrow heavily from the French, which was met with widespread revolt and a revolution that deposed him in 1908 in favor of his brother Abd al-Hafid.

Accession to the throne

By the action of Ba Ahmad bin Musa, the Chamberlain of Hassan I of Morocco, Abd al-Aziz's accession to the sultanate was ensured with little fighting. Ba Ahmad became regent and for six years showed himself a capable ruler.[3] There were strong rumors that he was poisoned.

On his death in 1900 the regency ended, and Abd al-Aziz took the reins of government into his own hands and chose an Arab from the south, Sid Mehdi el Menebhi, as his chief adviser.[1]

Rule

As urged by his Georgian[4][5] or Circassian mother, the sultan sought advice and counsel from Europe and endeavored to act on it, but advice not motivated by a conflict of interest was difficult to obtain, and in spite of the unquestionable desire of the young ruler to do what was best for the country, wild extravagance both in action and expenditure resulted, leaving the sultan with a depleted exchequer and the confidence of his people impaired. His intimacy with foreigners and his imitation of their ways were sufficient to rouse strong popular opposition.[3]

While privately owned printing presses had been allowed since 1872, Abdelaziz passed a dhahīr in 1897 that regulated what could be printed, allowing the qadi of Fes to establish a board to censor publications, and requiring that the judges be notified of any publication, so as to "avoid printing something that is not permitted."[6] According to Abdallah Laroui, these restrictions limited the volume and variety of Moroccan publications at the turn of the century, and institutions such as al-Qarawiyyin University and Sufi zawiyas became dependent on imported texts from Egypt.[6]

His attempt to reorganize the country's finances by the systematic levy of taxes was hailed with delight, but the government was not strong enough to carry the measures through, and the money which should have been used to pay the taxes was employed to purchase firearms instead. And so the benign intentions of Mulai Abd el-Aziz were interpreted as weakness, and Europeans were accused of having spoiled the sultan and of being desirous of spoiling the country.[3]

When British engineers were employed to survey the route for a railway between Meknes and Fez, this was reported as indicating the sale of the country outright. The strong opposition of the people was aroused, and a revolt broke out near the Algerian frontier. Such was the state of things when the news of the Anglo-French Agreement of 1904 came as a blow to Abd-el-Aziz, who had relied on England for support and protection against the inroads of France.[3] See also the Ion Perdicaris affair.

Algeciras Conference

On the advice of Germany, Abdelaziz proposed an international conference at Algeciras in 1906 to consult upon methods of reform, the sultan's desire being to ensure a state of affairs which would leave foreigners with no excuse to interfere in the control of the country and thereby promote its welfare, which he had earnestly desired from his accession to power. This was not, however, the result achieved (see main article), and while on June 18 the sultan nonetheless ratified the resulting Act of the conference, which the country's delegates had found themselves unable to sign, the anarchic state into which Morocco fell during the latter half of 1906 and the beginning of 1907 revealed the young ruler as lacking sufficient strength to command the respect of his turbulent subjects.[3]

Bouhmara

Jilali Ben Idris al-Yusufi al-Zarhouni (Bouhmara) appeared in 1902 claiming to be Abdelaziz's older brother and the rightful heir to the throne. He had spent time in Fes and learned the politics of the Makhzen. The pretender to the throne established a rival makhzen, traded with Europe and collected duties, imported arms, granted Europeans mining rights in the Rif, and claimed to be the mahdi.[7]

Raisuni

Ahmed er-Raisuni, a warlord with Alawite ancestry, started a gang near Tangier that would kidnap Christians, including Ion Perdicaris, Walter Burton Harris, and Harry Aubrey de Vere Maclean, and ransom them—in open defiance of the Makhzen of Abdelaziz.[7]

Oujda

Émile Mauchamp, a French doctor, was assassinated by a mob in Marrakesh March 19, 1907. France took his death as a pretext to invade Oujda from Algeria on March 29.[7][8]

Casablanca

In July 1907, tribesmen of the Chaouia—demanding removal of the French officers from the customs house, an immediate halt on the construction of the port, and the destruction of the railroad crossing over the Sidi Belyout cemetery—incited a riot in Casablanca, calling for holy war.[9] European railroad workers were killed, leading to Casablanca's bombardment and occupation by France.[9]

Hafidiya

A few months earlier in May 1907, the southern aristocrats, led by the head of the Glaoua tribe Si Elmadani El Glaoui, invited Abdelhafid, an elder brother of Abdelaziz, and viceroy at Marrakech, to become sultan, and the following August Abdelhafid was proclaimed sovereign there with all the usual formalities.[3]

In September, Abd-el-Aziz arrived at Rabat from Fez and endeavored to secure the support of the European powers against his brother. From France he accepted the grand cordon of the Legion of Honour, and was later enabled to negotiate a loan. This was seen as leaning to Christianity and aroused further opposition to his rule, and in January 1908 he was declared deposed by the ulema of Fez, who offered the throne to Hafid.[3]

End of rule

After months of inactivity Abdelaziz made an effort to restore his authority, and quitting Rabat in July he marched on Marrakech. His force, largely owing to treachery, was completely overthrown on August 19 when nearing that city,[1] and Abdelaziz fled to Settat, within the French lines around Casablanca. In November he came to terms with his brother, and thereafter took up his residence in Tangier as a pensioner of the new sultan.[3] However the exercise of Moroccan law and order continued to deteriorate under Abdelhafid, leading to the humiliating Treaty of Fez in 1912, in which European nations assumed many responsibilities for the sultanate, which was divided into three zones of influence.

Exile and death

Sultan Abdelaziz led a very active social but only semipolitical life in exile. During the Spanish annexation of Tangier in 1940, he acquiesced insofar as the Moroccan palace authorities called the "makhzen" played a significant role therein.

Abdelaziz died in Tangier in 1943. His body was transported to Fez, where he was buried in the royal necropolis of the Moulay Abdallah Mosque.[10]

Legacy

After the ex-sultan's sudden death in 1943, his body was transferred to French Morocco as desired by the Sultan Mohammed V.

He was portrayed by Marc Zuber in the film The Wind and the Lion (1975), a fictional version of the Perdicaris affair.

Honours

United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) - 2 July 1901[11]

United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) - 2 July 1901[11].svg.png.webp) Prussia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 1st Class of the Kingdom of Prussia - 1905

Prussia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 1st Class of the Kingdom of Prussia - 1905 France: Grand Cross of the Legion d'Honneur of France - 1907

France: Grand Cross of the Legion d'Honneur of France - 1907

See also

- List of Kings of Morocco

- History of Morocco

Notes

- "Abd al-Aziz". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 14. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- There is a dispute on the exact date of birth with two dates given: Feb 24, 1878 or Feb 18, 1881, while Chisholm (1911) states 1880.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abd-el-Aziz IV". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 32.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abd-el-Aziz IV". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 32. - FIGHT EXPECTED AT FEZ.; Rebels Only Four Hours from Capital at Last Report. LONDON TIMES -- NEW YORK TIMES Special Cablegram. January 2, 1903

- American Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events, Volume 19; Volume 34, D. Appleton, 1895, p.501

- "يومية «المساء» تروي قصة دخول المطبعة إلى المغرب". هوية بريس (in Arabic). 2014-05-04. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. France and Spain in Morocco. A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–119. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139045834.008. ISBN 978-1-139-04583-4.

- Yabiladi.com. "29 mars 1907 : Quand la France occupait Oujda en réponse à l'assassinat d'Émile Mauchamp". www.yabiladi.com (in French). Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Adam, André (1963). Histoire de Casablanca: des origines à 1914. Aix En Provence: Annales de la Faculté des Lettres Aix En Provence, Editions Ophrys. p. 62.

- Bressolette, Henri (2016). A la découverte de Fès. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2343090221.

- "No. 27329". The London Gazette. 2 July 1901. p. 4399.

References

- Jerome et Jean Tharaud, Marrakech ou les Seigneurs de l'Atlas

- Benumaya, Gil (1940). El Jalifa en Tanger. Madrid: Instituto Jalifiano de Tetuan

External links

Media related to Abdelaziz of Morocco at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abdelaziz of Morocco at Wikimedia Commons- Morocco Alaoui dynasty

- History of Morocco

- El Protectorado español en Marruecos: la historia trascendida

| Preceded by Hassan I |

Sultan of Morocco 1894–1908 |

Succeeded by Abdelhafid |