Cape Peninsula

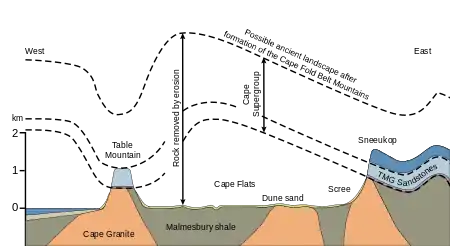

The Cape Peninsula (Afrikaans: Kaapse Skiereiland) is a generally rocky peninsula that juts out into the Atlantic Ocean at the south-western extremity of the African continent. At the southern end of the peninsula are Cape Point and the Cape of Good Hope. On the northern end is Table Mountain, overlooking Cape Town, South Africa. The peninsula is 52 km long from Mouille point in the north to Cape Point in the south.[1] The Peninsula has been an island on and off for the past 5 million years, as sea levels fell and rose with the ice age and interglacial global warming cycles of, particularly, the Pleistocene.[2] The last time that the Peninsula was an island was about 1.5 million years ago.[2] Soon afterwards it was joined to the mainland by the emergence from the sea of the sandy area now known as the Cape Flats. The towns and villages of the Cape Peninsula and Cape Flats now form part of the City of Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality.

.JPG.webp)

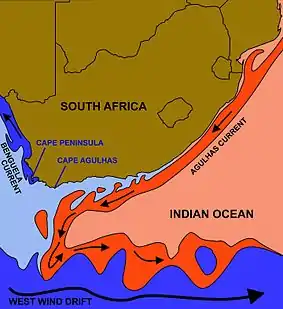

The Cape of Good Hope is sometimes erroneously identified as the meeting point of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. However, according to the International Hydrographic Organization agreement that defines the ocean boundaries, the meeting point is at Cape Agulhas, about 200 kilometres (120 mi) to the southeast and the most southerly tip of the African continent.[3][4][5] The west coast of the Peninsula is referred to as the "Atlantic Coast", "Atlantic Seaboard" or west coast,[6] but the eastern side is generally known as the "False Bay Coast".

Similarly, Cape Point is not the fixed "meeting point" of the cold Benguela Current, running northwards along the west coast of Africa, and the warm Agulhas Current, running south from the equator along the east coast of Africa. In fact the south flowing Agulhas Current swings away from the African coastline between about East London and Port Elizabeth, from where it follows the edge of the Continental shelf roughly as far as the southern tip of the Agulhas Bank, 250 km (155 miles) south of Cape Agulhas.[7] From there it is retroflexed (turned sharply round) in an easterly direction by the South Atlantic, South Indian and Southern Ocean currents, known as the "West Wind Drift", which flow eastwards round Antarctica. The Benguela Current, on the other hand, is an upwelling current which brings cold, mineral-rich water from the depths of the Atlantic Ocean to the surface along the west coast of Southern Africa. Having reached the surface it flows northwards as a result of the prevailing wind and Coriolis forces. The Benguela Current, therefore, effectively starts at Cape Point, and flows northwards from there,[7][8] although further out to sea it is joined by surface water that has crossed the South Atlantic from South America as part of the South Atlantic Gyre.[8] Thus the Benguela and Agulhas currents do not strictly "meet" anywhere, although eddies from the Agulhas current do from time to time round the Cape to join the Benguela Current.[7][8]

Ecology

Table Mountain National Park, previously known as the Cape Peninsula National Park, was proclaimed on 29 May 1998, for the purpose of protecting the natural environment of the Table Mountain Chain, and in particular the rare fynbos vegetation. The park comprises a large part of the undeveloped area of the Cape Peninsula, and is managed by South African National Parks Board. The coastal waters surrounding the Cape Peninsula were proclaimed as a marine protected area in 2004, include several no-take zones, and are part of the national park. The waters of this marine protected area are unusual in that they are parts of two fairly distinct marine ecoregions, namely the Agulhas ecoregion and the Benguela ecoregion. The boundary is at Cape Point.[9]

Flora

The Cape Peninsula has an unusually rich biodiversity. Its vegetation consists predominantly of several different types of the unique and rich Cape Fynbos. The main vegetation type is endangered Peninsula Sandstone Fynbos, but critically endangered Peninsula Granite Fynbos, Peninsula Shale Renosterveld and Afromontane forest occur in smaller portions on the mountain ranges of the Peninsula. On the sandy Cape Flats lowlands there are a few pockets of protected Cape Flats Sand Fynbos.

The Peninsula's vegetation types form part of the Cape Floral Region protected areas. These protected areas are a World Heritage Site, and an estimated 2,200 species of plants are confined to Table Mountain range - which are at least as many as occur in the whole of the United Kingdom.[13][14] Many of these species, including a great many types of proteas, are endemic to these mountains and can be found nowhere else. The Disa uniflora, despite its restricted range within the Western Cape, is relatively common in the perennially wet areas (waterfalls, streamlets and seeps) on Table Mountain and the Back Table, but hardly anywhere else on the Cape Peninsula.[12][15] It is a very showy orchid that blooms from January to March on the Table Mountain Sandstone regions of the mountain. Although they are quite widespread on the Back Table, the best (most certain, and close-up) place to view these beautiful blooms is in the "Aqueduct" off the Smuts Track, halfway between Skeleton Gorge and Maclear's Beacon.

Remnant patches of indigenous forest persist in the wetter ravines. However, much of the indigenous forest was felled by the early European settlers for fuel for the lime kilns needed during the construction of the Castle.[16] The exact extent of the original forests is unknown, though most of it was probably along the eastern slopes of Devil's Peak, Table Mountain and the Back Table where names such as Rondebosch, Kirstenbosch, Klaassenbosch and Witteboomen survive (in Dutch "bosch" means forest; and "boomen" means trees) . Hout Bay (in Dutch "hout" means wood) was another source of timber and fuel as the name suggests.[16] In the early 1900s commercial pine plantations were planted on these slopes all the way from the Constantiaberg to the front of Devil’s Peak, and even on top of the mountains, but these have now been largely cleared allowing fynbos to flourish in the regions where the indigenous Afromontane forests have not survived, or never existed.

Fynbos is a fire adapted vegetation, and evidence suggests that in the absence of regular fires all but the drier fynbos would become dominated by trees.[13][17] Regular fires have dominated fynbos for at least the past 12 000 years largely as a result of human activity.[14][18] In 1495 Vasco da Gama named the South African coastline Terra de Fume because of the smoke he saw from numerous fires.[17] This was originally probably to maintain a productive stock of edible bulbs (especially watsonians)[17] and to facilitate hunting, and later, after the arrival of pastoralists,[19] to provide fresh grazing after the rains.[17][18] Thus the plants that make up fynbos today are those that have been subjected to a variety of fire regimes over a very long period time, and their preservation now requires regular burning. The frequency of the fires obviously determines precisely which mix of plants will dominate any particular region,[20] but intervals of 10–15 years between fires[13] are considered to promote the proliferation of the larger Protea species, a rare local colony of which, the Aulax umbellata (Family: Proteaceae), was wiped out on the Peninsula by more frequent fires,[20] as have been the silky-haired pincushion, Leucospermum vestitum, the red sugarbush, Protea grandiceps and Burchell's sugarbush, Protea burchellii, although a stand of a dozen or so plants has recently been "rediscovered" in the saddle between Table Mountain and Devil's Peak.[17] Some bulbs may similarly have become extinct as a result of a too rapid sequence of fires.[20] The fires that occur on the mountains today are still largely due to unregulated human activity. Fire frequency is therefore a matter of chance rather than conservation.

Despite intensive conservation efforts the Table Mountain range has the highest concentration of threatened species of any continental area of equivalent size in the world.[13][21] The non-urban areas of the Cape Peninsula (mainly on the mountains and mountain slopes) have suffered particularly under a massive onslaught of invasive alien plants for well over a century, with perhaps the worst invader being the cluster pine, partly because it was planted in extensive commercial plantations along the eastern slopes of the mountains, north of Muizenberg. Considerable efforts have been made to control the rapid spread of these invasive alien trees. Other invasive plants include black wattle, blackwood, Port Jackson and rooikrans (All Australian members of the acacia family), as well as several Hakea species and bramble.[13][20][22]

Fauna

The most common mammal on the mountain was the dassie (the South African name, from Afrikaans, pronounced "dussy"), or rock hyrax. Between about 2000 and 2004 (no one is certain about the exact year or years) their numbers suddenly plummeted for unknown reasons. They used to cluster around the restaurant at the upper cable station, near areas where tourists discarded or (inadvisably supplied) food. The population crash of the dassies was in all probability responsible for the decline in the Verreaux's eagle population on the Peninsula, which is believed to have consisted of 3 breeding pairs during the period 1950 to 1990, with only 2 pairs, maximally, ever having been reported to fledge a chick each in any given year.[23] With the commencement of formal monitoring in 1993, two breeding pairs were recorded on the Cape Peninsula Mountain Chain in 2004: one below the upper cable station at the western end of Table Mountain, in Blinkwater Ravine, the other on the cliffs below Noordhoek Peak.[24] The nest near the cable station was abandoned in 2006, leaving only the Noordhoek pair, which continued to fledge chicks reasonably regularly till 2013, at which point one member of the pair disappeared. From 2013 till January 2017 only a single Verreaux's Eagle, presumed to be a female, remained on the Peninsula. She continued to maintain the nest under Noordhoek Peak, but seemed unable to attract a mate. But in early 2017 a pair of eagles was seen by at least 7 independent observers during the course of 10 days (27 January - 5 February). It remains to be seen whether they will breed later in the year. Dassies are an important part the Verreaux's eagle's prey on the Peninsula.[25] (See Foot note[nb 1])

Table Mountain is also home to porcupines, mongooses, snakes, lizards, tortoises, and a rare endemic species of amphibian that is only found on Table Mountain, the Table Mountain ghost frog. The last lion in the area was shot circa 1802. Leopards persisted on the mountains until perhaps the 1920s but are now extinct locally. Two smaller, secretive, nocturnal carnivores, the rooikat (caracal) and the vaalboskat (also called the vaalkat or Southern African wildcat) were once common in the mountains and the mountain slopes. The rooikat continues to be seen on rare occasions by mountaineers but the status of the vaalboskat is uncertain. The mountain cliffs are home to several raptors species, apart from the Verreaux's eagle. They include the jackal buzzard, booted eagle (in summer), African harrier-hawk, peregrine falcon and the rock kestrel.[25][26] In 2014 three pairs of African fish eagles were believed to be breeding on the Peninsula, but they nest in trees generally as far away from human habitation as is possible on the Peninsula. Their number in 2017 is unknown.

Up until the late 1990s baboons occurred on all the mountains of the Peninsula, including the Back Table immediately behind Table Mountain. Since then they have abandoned Table Mountain and the Back Table, and only occur on the Constantiaberg, and the mountains to the south. They have also abandoned the tops of many of the mountains, in favour of the lower slopes, particularly when these were covered in pine plantations which seemed to provide them with more, or higher quality food than the fynbos on the mountain tops. However these new haunts are also within easy reach of Cape Town's suburbs, which brings them into conflict with humans and dogs, and the risk of traffic accidents. In 2014 there were a dozen troops on the Peninsula, varying in size from 7 to over 100 individuals, scattered on the mountains from the Constantiaberg to Cape Point.[27][28] The baboon troops are the subject of intense research into their movements (both of individuals and of the troops), their physiology, genetics, social interactions and habits. In addition, their sleeping sites are noted each evening, so that monitors armed with paint ball guns can stay with the troop all day, to ward them off from wandering into the suburbs. From when this initiative was started in 2009 the number of baboons on the Peninsula has increased from 350 to 450, and the number of baboons killed or injured by residents has decreased.[28]

Himalayan tahrs, fugitive descendants of tahrs that escaped from Groote Schuur Zoo near the University of Cape Town, in 1936, used to be common on the less accessible upper parts of the mountain. As an exotic species, they were almost eradicated through a culling programme initiated by the South African National Parks to make way for the reintroduction of indigenous klipspringers. Until recently there were also small numbers of fallow deer of European origin and sambar deer from southeast Asia. These were mainly in the Rhodes Memorial area but during the 1960s they could be found as far afield as Signal Hill. These animals may still be seen occasionally despite efforts to eliminate or relocate them.

On the lower slopes of Devil's Peak, above Groote Schuur Hospital, an animal camp bequeathed to the City of Cape Town by Cecil John Rhodes has been used in recent years as part of the Quagga Project.[29] The quaggas used to roam the Cape Peninsula, the Karoo and the Free State in large numbers, but were hunted to extinction during the early 1800s. The last quagga died in an Amsterdam zoo in 1883. In 1987 a project was launched by Reinhold Rau to back-breed the quagga, after it had been established, using mitochondrial DNA obtained from museum specimens, that the quagga was closely related to the plains zebra, and on 20 January 2005 a foal considered to be the first quagga-like individual because of a visible reduced striping was born. These quagga-like zebras are officially known as Rau quaggas, as no one can be certain that they are anything more than quagga look-alikes. The animal camp above Groote Schuur Hospital has several good looking Rau quaggas, but they are unfortunately not easily seen except from within the game camp, which is quite large and undulating, and the animals are few. The animal camp is not open to the public.

Geology

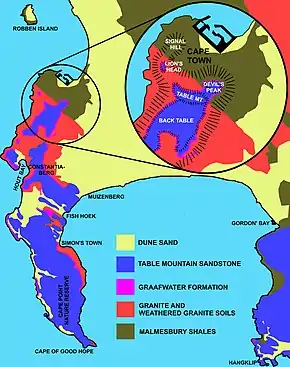

The Cape Peninsula is underlain by the oldest rocks in the area, the Malmesbury Group, and the granite intrusions of the Peninsula pluton.

The Malmesbury Group has been dated from between 830 and 980 Mya, and was deformed during the Saldanian orogenic cycle, both before and during the granite intrusions of 630 to 500 Mya, and there are minor intrusions which precede the granite. The base of this group has not been exposed.[30] The basal rocks were eroded to a relatively featureless peneplain with exposed granites covering most of the peninsula south of Lion's Head and Devil's Peak. The Sea-Point contact zone, described by Charles Darwin is a well known region of metamorphic rocks formed by the (originally very hot) granite intrusion into the Malmesbury rocks.[2]

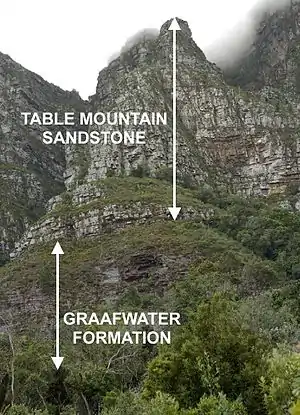

These rocks were later unconformably covered by the Cape Supergroup. The Cape Supergroup is divided into eight formations, the three oldest of which are present on the Peninsula. The lowest present is the reddish Graafwater formation which consist of shales and sandstone. The Graafwater Formation can be clearly seen in the cutting on the second hairpin bend as the Ou Kaapse Weg (road) goes up the slope from Westlake on to the Silvermine plateau. In the cutting one can also see the abrupt and obvious transition into the Table Mountain Sandstone (or, as it is currently known, the Peninsula Formation Sandstone) above it. Looking up the slope from below to the first hairpin bend, the granite basement on which the Graafwater formation rests is visible. And in the cutting at the first hairpin bend, the ocher-colored, gritty clay into which the granite weathers is clearly displayed. The relatively thin Graafwater layer (no more than about 60–70 m thick on the Cape Peninsula) is overlain by the prominent Peninsula Formation, which consist mainly of hard, erosion resistant, quartzitic sandstone, which form the high, prominent, almost vertical cliffs of the Cape Peninsula. At the very top of Table Mountain, at Maclear's Beacon, is a small remnant of the Pakhuis Diamictites, better represented in the Cederberg Mountains, 200 km to the north of Cape Town.[30]

Foot note

- In 2011-2012 dassies began to be seen in Bakoven, on the Atlantic coast, below the Twelve Apostles Mountains. They were then seen in the Silvermine region of the Table Mountain National Park, and in 2015 at the restaurant on the top of the western end of Table Mountain, as well as elsewhere in the mountains. But even in 2017 dassies are still not as abundant as they were on the Peninsula Mountain Chain in the 1990s.

References

- 1:250,000 Geological Series map 3318:Cape Town, Government Printer, Pretoria, 1990.

- Compton, John S. (2004) The Rocks & Mountains of Cape Town. Cape Town: Double Story. ISBN 978-1-919930-70-1

- Limits of Oceans and Seas UNESCO Special Publication no. 23, 3rd ed., 1953

- Where the two oceans really meet, 18 December 2007

- "Cape Point And The Waters Of False Bay..." Simonstown.com. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- The Atlantic Coast. Discover the Cape.

- Branch, M & Branch G. (1981). The Living Shores of Southern Africa. pp. 14-18. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

- Tyson, P.D., Preston-Whyte, R.A. (2000) The Weather and Climate of Southern Africa. pp. 221-223. Oxford University Press, Cape Town

- Sink, K; Holness, S; Harris, L; Majiedt, P; Atkinson, L; Robinson, T; Kirkman, S; Hutchings, L; Leslie, R; Lamberth, S; Kerwath, S; von der Heyden, S; Lombard, A; Attwood, C; Branch, G; Fairweather, T.; Taljaard, S.; Weerts, S.; Cowley, P.; Awad, A.; Halpern, B.; Grantham, H; Wolf, T. (2012). National Biodiversity Assessment 2011: Technical Report (PDF) (Report). Volume 4: Marine and Coastal Component. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute. p. 325. Note: This is the full document, with numbered pages.

- Manning, John (2007). "Cone Bush, Tolbos". In: Field Guide to Fynbos. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. p. 258. ISBN 9781770072657.

- http://www.proteaatlas.org.za/cpldarge.htm

- Trinder-Smith, Terry (2006). "Orchidaceae". In: Wild Flowers of the Table Mountain National Park. Kirstenbosch, Claremont: Botanical Society of South Africa. pp. 104–105. ISBN 1874999600.

- Manning, John (2007). "The World of Fynbos". In: Field Guide to Fynbos. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. pp. 8–23. ISBN 9781770072657.

- Trinder-Smith, Terry (2006). "Introduction". In: Wild Flowers of the Table Mountain National Park. Cape Town: Botanical Society of South Africa. pp. 19–35. ISBN 1874999600.

- Manning, John (2007). "Disa". In: Field Guide to Fynbos. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. pp. 162–163. ISBN 9781770072657.

- Sleigh, Dan (2002). Islands. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 429. ISBN 0436206323.

- Pauw, Anton; Johnson, Steven (1999). "The Power of Fire". in: Table Mountain. Vlaeberg, South Africa: Fernwood Press. pp. 37–53. ISBN 1-874950-43-1.

- Kraaij, Tineke; van Wilgen, Brian W. (2014). "Drivers, ecology, and management of fynbos fires.". In Allsopp, Nicky; Colville, Jonathan F.; Verboom, G. Anthony (eds.). Fynbos, Ecology, Evolution and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780199679584.

- Saunders, Christopher; Bundy, Colin, eds. (1992). "A way of life perfected". Readers' Digest Illustrated History of South Africa. Cape Town: Reader’s Digest Association Ltd. pp. 20–25. ISBN 0-947008-90-X.

- Maytham Kid, Mary (1983). "Introduction". In: Cape Peninsula. South African Wild Flower Guide 3. Kirstenbosch, Claremont: Botanical Society of South Africa. p. 27. ISBN 0620067454.

- "Perceval" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-25.

- "Brochures, booklets and posters". Capetown.gov.za. Archived from the original on 2012-12-23. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- Information gleaned from reports in the Cape Bird Club's newsletters from the 1950s onwards

- Jenkins, A.R.; van Zyl, A.J. (2005). "Conservation status and community structure of cliff-nesting raptors and ravens on the Cape Peninsula, South Africa". Ostrich. 76 (3–4): 175–184. doi:10.2989/00306520509485490. ISSN 0030-6525.

- Hockey, P. A. R.; Dean, W. R. J.; Ryan, P. G., eds. (2005). Roberts Birds of Southern Africa (Seventh ed.). Cape Town: John Voelcker Bird Book Fund. pp. 531–532. ISBN 0-620-34053-3.

- Jenkins, Andrew; van Zyl, Anthony (2002). "Home on the range. Raptor riches of the Cape Peninsula". Africa Birds & Birding. 7: 38–46.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2014-06-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Cape Peninsula Baboon Research Unit

- http://www.ncc-group.co.za/case-studies/managing-baboon-human-conflict-city-cape-town Managing Baboon-human conflict: City of Cape Town

- http://www.quaggaproject.org/ The Quagga Project South Africa

- Theron, J.N. Gresse, P.G. Siegfried, H.P. and Rogers, J. Explanation sheet 3318 – The Geology of the Cape Town Area. Geological Survey, Department of Mineral and Energy Affairs, Government Printer, Pretoria 1992. ISBN 978-0-621-14284-6

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cape Peninsula. |