Elections lost by presidents of the United States

As most presidents have careers in politics and some lose re-election, there have been many elections lost by presidents of the United States.

This list does not include individual primary losses, but does include unsuccessful attempts to be nominated.

George Washington

Virginia House of Burgesses election, 1757

Washington first stood for election to the Virginia House of Burgesses from Frederick County, Virginia in 1757 at the age of 25. Two burgesses were elected from each Virginia county by and among the male landowners. Members of the House of Burgesses did not serve fixed terms, unlike its successor the Virginia House of Delegates, and it remained sitting until dissolved by the governor or until seven years had passed, whichever occurred sooner.[1]

Elections during this time were not conducted by secret ballot but rather by viva voce. The sheriff of the county, a clerk, and a representative of each candidate would be seated at a table, and each elector would approach the table and openly declare his vote. In elections to the House of Burgesses, each voter cast two votes and two candidates were elected who received the greatest number of votes.[2]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | Hugh West | 271 | 46.64 | |

| Independent | Thomas Swearingen | 270 | 46.47 | |

| Independent | George Washington | 40 | 6.88 | |

John Adams

.jpg.webp)

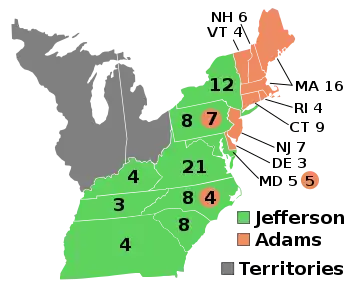

United States presidential election, 1800

With the Federalist Party deeply split over his negotiations with France, and the opposition Republican Party enraged over the Alien and Sedition Acts and the expansion of the military, Adams faced a daunting reelection campaign in 1800.[4] The Federalist congressmen caucused in the spring of 1800 and nominated Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. The Republicans nominated Jefferson and Burr, their candidates in the previous election.[5]

The campaign was bitter and characterized by malicious insults by partisan presses on both sides. Federalists claimed that the Republicans were the enemies of "all who love order, peace, virtue, and religion." They were said to be libertines and dangerous radicals who favored states' rights over the Union and would instigate anarchy and civil war.

When the electoral votes were counted, Adams finished in third place with 65 votes, and Pinckney came in fourth with 64 votes. Jefferson and Burr tied for first place with 73 votes each. Because of the tie, the election devolved upon the House of Representatives, with each state having one vote and a supermajority required for victory. On February 17, 1801 – on the 36th ballot – Jefferson was elected by a vote of 10 to 4 (two states abstained).[4][6] Hamilton's scheme, although it made the Federalists appear divided and therefore helped Jefferson win, failed in its overall attempt to woo Federalist electors away from Adams.[7][lower-alpha 1]

Thomas Jefferson

United States presidential election, 1796

Thomas Jefferson lost the presidential election of 1796 to John Adams.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| John Adams | Federalist | Massachusetts | 35,726 | 53.4% | 71 |

| Thomas Jefferson | Democratic-Republican | Virginia | 31,115 | 46.6% | 68 |

| Thomas Pinckney | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 59 |

| Aaron Burr | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 30 |

| Samuel Adams | Democratic-Republican | Massachusetts | — | — | 15 |

| Oliver Ellsworth | Federalist | Connecticut | — | — | 11 |

| George Clinton | Democratic-Republican | New York | — | — | 7 |

| John Jay | Federalist | New York | — | — | 5 |

| James Iredell | Federalist | North Carolina | — | — | 3 |

| George Washington | None | Virginia | — | — | 2 |

| John Henry | Federalist[11] | Maryland | — | — | 2 |

| Samuel Johnston | Federalist | North Carolina | — | — | 2 |

| Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 66,841 | 100.0% | 276 | ||

| Needed to win | 70 | ||||

James Madison

Virginia House of Delegates election, 1777

Madison lost re-election to the Virginia House of Delegates in the 1777 election.[12]

James Monroe

Democratic-Republican presidential caucus, 1808

Nominations for the 1808 presidential election were made by congressional caucuses. With Thomas Jefferson ready to retire, supporters of Secretary of State James Madison of Virginia worked carefully to ensure that Madison would succeed Jefferson. Madison's primary competition came from former Ambassador James Monroe of Virginia and Vice President George Clinton. Monroe was supported by a group known as the tertium quids, who supported a weak central government and were dissatisfied by the Louisiana Purchase and the Compact of 1802. Clinton's support came from Northern Democratic-Republicans who disapproved of the Embargo Act (which they saw as potentially leading towards war with Great Britain) and who sought to end the Virginia Dynasty. The Congressional caucus met in January 1808, choosing Madison as its candidate for president and Clinton as its candidate for vice president.[13]

Many supporters of Monroe and Clinton refused to accept the result of the caucus. Monroe was nominated by a group of Virginia Democratic-Republicans, and although he did not actively try to defeat Madison, he also refused to withdraw from the race.[14] Clinton was also supported by a group of New York Democratic-Republicans for president even as he remained the party's official vice presidential candidate.[15]

| Presidential Ballot | Total | Vice Presidential Ballot | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| James Madison | 83 | George Clinton | 79 |

| James Monroe | 3 | John Langdon | 5 |

| George Clinton | 3 | Henry Dearborn | 3 |

| John Quincy Adams | 1 |

John Quincy Adams

United States House of Representatives election, 1802

Adams lost.

United States presidential election, 1828

Adams lost to Andrew Jackson.

Massachusetts gubernatorial election, 1833

The Anti-Masonic Party nominated Adams in the 1833 Massachusetts gubernatorial election in a four-way race between Adams, the National Republican candidate, the Democratic candidate, and a candidate of the Working Men's Party. The National Republican candidate, John Davis, won 40% of the vote, while Adams finished in second place with 29%. Because no candidate won a majority of the vote, the state legislature decided the election. Rather than seek election by the legislature, Adams withdrew his name from contention, and the legislature selected Davis.[16]

U.S. Senate election, 1835

Adams was nearly elected to the Senate (to represent Massachusetts) in 1835 by a coalition of Anti-Masons and National Republicans, but his support for Jackson in a minor foreign policy matter annoyed National Republican leaders enough that they dropped their support for his candidacy.[17] After 1835, Adams never again sought higher office, focusing instead on his service in the House of Representatives.[18]

Andrew Jackson

United States presidential election, 1824

Andrew Jackson lost to John Quincy Adams, despite winning a greater share of the popular vote.

Martin Van Buren

1840 United States presidential election

President van Buren lost to William Henry Harrison.

William Henry Harrison

Ohio gubernatorial election, 1820

Harrison lost the race for Ohio governor.

United States House of Representatives election, 1822

Harrison lost to James W. Gazlay to represent Ohio's 1st congressional district.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic-Republican | James W. Gazlay | 3,176 | 52.85% | |

| Democratic-Republican | William H. Harrison | 2,834 | 47.15% | |

| Total votes | 6,010 | 100% | ||

United States presidential election, 1836

Harrison lost to Martin van Buren. He would go on to defeat Van Buren in the 1840 presidential election.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| Martin Van Buren | Democratic | New York | 764,176 | 50.83% | 170 |

| William Henry Harrison | Whig | Ohio | 550,816 | 36.63% | 73 |

| Hugh Lawson White | Whig | Tennessee | 146,107 | 9.72% | 26 |

| Daniel Webster | Whig | Massachusetts | 41,201 | 2.74% | 14 |

| Willie Person Mangum | Whig | North Carolina | —(b) | — | 11 |

| Other | 1,234 | 0.08% | 0 | ||

| Total | 1,503,534 | 100.0% | 294 | ||

| Needed to win | 148 | ||||

John Tyler

United States presidential election, 1844

Tyler, having sought election to a full term with the nomination of the newly-formed National Democratic-Republican Party, dropped out of the race on August 20, 1844.

Lost races

Not including presidential re-election attempts made while in office.

Presidential elections

Congressional and gubernatorial elections

Other elections

| President | Office and jurisdiction | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Tyler | Vice President of the United States | 1836 | One of two Whig vice presidential candidates. Came in third behind Richard Mentor Johnson and Francis Granger. Later elected in 1840. |

| Millard Fillmore | Whig nomination for Vice President of the United States |

1844 | Lost to Theodore Frelinghuysen. Later won in 1848. |

| Abraham Lincoln | Republican nomination for Vice President of the United States |

1856 | Lost to William L. Dayton |

| Grover Cleveland | District Attorney for Erie County, New York | 1865 | Lost to Lyman K. Bass |

| Theodore Roosevelt | Mayor of New York City | 1886 | Placed in distant third behind Abram S. Hewitt and Henry George. |

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | Vice President of the United States | 1920 | Lost to Calvin Coolidge. |

| Harry S. Truman | Judge of Jackson County, Missouri | 1924 | Lost to Henry Rummel |

| John F. Kennedy | Democratic nomination for Vice President of the United States |

1956 | Lost to Estes Kefauver. |

Notes

- Ferling attributes Adams's defeat to five factors: the stronger organization of the Republicans; Federalist disunity; the controversy surrounding the Alien and Sedition Acts; the popularity of Jefferson in the South; and the effective politicking of Burr in New York.[8] Adams wrote, "No party that ever existed knew itself so little or so vainly overrated its own influence and popularity as ours. None ever understood so ill the causes of its own power, or so wantonly destroyed them."[9] Stephen G. Kurtz argues that Hamilton and his supporters were primarily responsible for the destruction of the Federalist Party. They viewed the party as a personal tool and played into the hands of the Jeffersonians by building up a large standing army and creating a feud with Adams.[10] Chernow writes that Hamilton believed that by eliminating Adams, he could eventually pick up the pieces of the ruined Federalist Party and lead it back to dominance: "Better to purge Adams and let Jefferson govern for a while than to water down the party's ideological purity with compromises."[7]

References

- Gottlieb, Matthew. "House of Burgesses". encyclopediavirginia.org. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Beeman, Richard (2015). The Varieties of Political Experience in Eighteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 39–43. ISBN 978-0812201215.

- "The First Election of Washington to the House of Burgesses". newrivernotes.com. Grayson County Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Taylor, C. James. "John Adams: Campaigns and Elections". Charlottesville, VA: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Ferling, ch. 19.

- "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". College Park, Maryland: Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- Chernow 2004, p. 626.

- Ferling 1992, pp. 404–405.

- Smith 1962b, p. 1053.

- Kurtz 1957, p. 331.

- "MARYLAND'S ELECTORAL VOTE FOR U.S. PRESIDENT, 1789-2016". Maryland Manual On-line. Maryland State Archives. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Burstein & Isenberg 2010, pp. 59–60

- Sabato, Larry; Ernst, Howard (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections. Infobase Publishing. pp. 302–304.

- Ammon, Harry (1963). "James Monroe and the Election of 1808 in Virginia". The William and Mary Quarterly. 20 (1): 33–56. doi:10.2307/1921354. JSTOR 1921354.

- Kaminski, John P. (1993). George Clinton: Yeoman Politician of the New Republic. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 281–288. ISBN 9780945612186. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 284–285.

- Cooper 2017, pp. 311–312.

- Cooper 2017, p. 315.

- "Ohio U.S. House of Representatives election, 1822".