Hastings-on-Hudson, New York

Hastings-on-Hudson is a village in Westchester County located in the southwest part of the town of Greenburgh in the state of New York, United States. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, about 20 miles (32 km) north of midtown Manhattan in New York City, and is served by a stop on the Metro-North Hudson Line. To the north of Hastings-on-Hudson is the village of Dobbs Ferry, to the south, the city of Yonkers, and to the east unincorporated parts of Greenburgh. As of the 2017 ACS 5-year population estimate, it had a population of 8,903.[3] The town lies on U.S. Route 9, "Broadway", along with the Saw Mill River Parkway and I-287.

Hastings-on-Hudson, New York | |

|---|---|

Municipal building | |

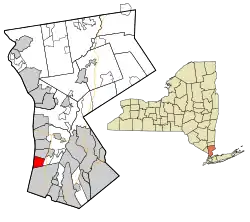

Location of Hastings-on-Hudson, New York | |

| Coordinates: 40°59′28″N 73°52′27″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Westchester |

| Town | Greenburgh |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.94 sq mi (7.62 km2) |

| • Land | 1.98 sq mi (5.13 km2) |

| • Water | 0.96 sq mi (2.49 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 7,849 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 7,853 |

| • Density | 3,968.17/sq mi (1,532.11/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 10706 |

| Area code(s) | 914 |

| FIPS code | 36-32710 |

| Website | http://hastingsgov.org/ |

History

The area that is now Hastings-on-Hudson was once the home of the Weckquaesgeek, an Algonquian tribes. In the summer, the Weckquaesgeeks camped at the mouth of the ravine running under the present Warburton Avenue Bridge. There they fished, swam and collected oysters and clamshells used to make wampum. On the level plain nearby (which is now Maple Avenue), they planted corn and possibly tobacco.

Pre-1920

Around 1650, a Dutch carpenter, named Frederick Philipse, arrived in New Amsterdam. In 1682, Philipse traded with the Native Americans for the area that is now Dobbs Ferry and Hastings-on-Hudson. In 1693, the English Crown granted Philipse the Manor of Philipsburg, which included what is now Hastings-on-Hudson. After dividing the area into four nearly equal-sized farms, the Philipses leased them to Dutch, English and French Huguenot settlers.

During the American Revolution, what is now Hastings-on-Hudson, lay between the lines of the warring forces and was declared neutral territory. In reality, the area became a no-man's land and was raided repeatedly by both sides. The minor Revolutionary War skirmish known as the Battle of Edgar's Lane was fought in Hastings. Following the Revolution, the Philipses, who had been loyal to George III, saw their vast lands confiscated and sold by the newly established American state. In 1785, the four farms comprising today's Hastings-on-Hudson were bought by James DeClark, Jacobus Dyckman, George Fisher, and tavern keeper Peter Post.

Around the same time, Westchester County, which had been established as one of the 10 original counties in New York, was divided into towns, and the area that is now Hastings-on-Hudson became part of the town of Greenburgh. The village was incorporated in 1879 and its name changed from Hastings-Upon-Hudson to Hastings-on-Hudson.

Stone quarrying was the earliest industry in Hastings-on-Hudson. From 1865 to 1871, hundreds of Scottish and Irish laborers blasted huge quantities of dolomitic marble from a white Westchester marble quarry. An inclined railroad carried the marble down to the quarry wharf where it was dressed by skilled stonecutters and loaded onto ships bound for cities like New York and Charleston, South Carolina.

By the 1880s, Hastings Pavement was producing hexagonal paving blocks which were used extensively in Central Park and Prospect Park in Brooklyn. Between 1895 and 1900, Hastings Pavement produced 10 million such blocks and shipped them throughout the United States and to cities in Canada, Brazil and England. By 1891, the National Conduit and Cable Company had established an operation on the waterfront producing cables for utility companies here and abroad. In 1912, labor strife between striking workers and their employer, the National Cable and Conduit Company, left two striking workers and two bystanders dead. Similar labor unrest occurred in 1916, whereby the Village was put under house arrest.

During World War I, 200 National Guardsmen were stationed in Hastings-on-Hudson because of the security interests of the National Conduit plant and a chemical plant opened by Frederick G. Zinsser that produced a wood alcohol called Hastings Spirits.[4]

1920-recent

The Anaconda Copper Company took over National Conduit in 1929, and a few years later acquired the Hastings Pavement property. By the end of World War II, Anaconda owned most of the industrial waterfront. Anaconda closed its Hastings-on-Hudson plant in 1975, bringing to an end the century-long era of heavy industry on the Hastings-on-Hudson waterfront.[4]

The 1926-founded Hillside-on-Hastings sanitarium and hospital opened in 1926.[5] They relocated to Glen Oaks, Queens in 1941.[6]

Billie Burke, actress (the "Good Witch" in the Wizard of Oz) lived in Hastings-on-Hudson and left her property to the school district, which still owns it, and uses it for various sports.

Benjamin Franklin Goodrich, from Ripley, in western New York, used real estate profits to purchase the Hudson River Rubber Company, a small business in Hastings-on-Hudson. The following year, Goodrich relocated the business to Akron, Ohio.

Children's Village, a boarding facility for children in difficult circumstances, located in neighboring Dobbs Ferry, sold about 50 acres (200,000 m2) of its property in Hastings-on-Hudson to a developer in 1986. The developer was planning to build close to 100 homes that would result in traffic on the roads adjoining Hillside Elementary School. Local residents formed a committee called "Save Hillside Woods" and raised close to $800K. As a result of the 1987 stock market crash and the subsequent receivership of the bank that held the mortgage on the property, the Village purchased this parcel from the FDIC with the funds accumulated and a bond floated by the Village of Hastings-on-Hudson to expand and maintain Hillside Woods.

The Jasper F. Cropsey House and Studio and Hastings Prototype House are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The John William Draper House is listed as a National Historic Landmark[7]

Geography

Hastings-on-Hudson is located at 40°59′28″N 73°52′27″W (40.991102, -73.874114)[8] in an area of hills on the Hudson River opposite the Palisades cliffs, north of the city of Yonkers. The Village is bordered by the Hudson River to the west, and the Saw Mill River to the east. The areas facing the Hudson River have views of the Palisades to the west, Manhattan to the south and the Mario Cuomo Bridge to the north.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the Village has a total area of 2.9 square miles (7.5 km2), of which 2.0 square miles (5.2 km2) is land and 0.9 square miles (2.3 km2), or 32.65%, is water.

Transportation

Although a suburb of New York City, Hastings-on-Hudson enjoys better mass transit service than many other suburbs in the United States. Commuter rail service is available via the Hastings-on-Hudson railway station, served by the Metro-North Railroad's Hudson Line to Grand Central Terminal, Croton-on-Hudson and Poughkeepsie; transfers to Amtrak's Empire Corridor are available three stops south, at the Yonkers railway station. Additionally, several bus routes operated by the Bee-Line Bus System, connect Hastings-on-Hudson with other places in Westchester and northern sections of the Bronx.

The Saw Mill River Parkway has exits in Hastings-on Hudson - Northbound at Exit 12 at Farragut Parkway and Exit 13 at Farragut Avenue, and Southbound Exit 14 at Clarence Avenue and Exit 15 at Cliff Street. US Route 9 runs through the Village, as Broadway.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 1,290 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,466 | 13.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,002 | 36.6% | |

| 1910 | 4,552 | 127.4% | |

| 1920 | 5,526 | 21.4% | |

| 1930 | 7,097 | 28.4% | |

| 1940 | 7,057 | −0.6% | |

| 1950 | 7,565 | 7.2% | |

| 1960 | 8,979 | 18.7% | |

| 1970 | 9,479 | 5.6% | |

| 1980 | 8,573 | −9.6% | |

| 1990 | 8,000 | −6.7% | |

| 2000 | 7,648 | −4.4% | |

| 2010 | 7,849 | 2.6% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 7,853 | [2] | 0.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] | |||

As of the census[10] of 2000, there were 7,648 people, 3,093 households, and 2,090 families residing in the Village. The population density was 3,899.7 people per square mile (1,506.6/km2). There were 3,193 housing units at an average density of 1,628.1 per square mile (629.0/km2). The racial makeup of the Village was 89.79% (7,155) White, 2.35% (187) African American, 0.17% (13) Native American, 4.14% (328) Asian, 1.82% from other races, and 1.73% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.50% (358) of the population.

There were 3,093 households, out of which 33.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.0% were married couples living together, 8.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.4% were non-families. 27.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 3.05.

In the Village, the population was spread out, with 25.0% under the age of 18, 4.1% from 18 to 24, 26.1% from 25 to 44, 29.3% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.9 males.

The median income for a household in the Village was $83,188, and the median income for a family was $129,227. Males had a median income of $76,789 versus $50,702 for females. The per capita income for the Village was $48,914. About 1.5% of families and 3.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.7% of those under age 18 and 1.9% of those age 65 or over.

In 2013, the infusion of urban professionals from New York City resulted in characterization of the town as an example of "hipsturbia", a neologism coined by The New York Times to describe the hip lifestyle as lived in suburbia by "hipsters."[11] However, this article has been the subject of much controversy both within and with-out the community, with the New York Observer publishing one particularly scathing commentary.[12]

Education

Hastings-on-Hudson has three public schools, in the Hastings Union Free School District: Hillside Elementary School, Farragut Middle School, and Hastings High School. All three have been awarded the National Blue Ribbon Award.

Attractions and recreation

In 2018 Brooke Lea Foster of The New York Times stated that it was one of several "Rivertowns" in New York State, which she described as among the "least suburban of suburbs, each one celebrated by buyers there for its culture and hip factor, as much as the housing stock and sophisticated post-city life."[13] Of those, Foster stated that Irvington was the "artsiest".[13]

Attractions and places for recreation include:

- Chemka Pool, a community outdoor swimming pool near the Hillside Woods/School

- Hillside Woods, a large wooded area with hiking and biking trails

- Two north-south linear parks: the Old Croton Aqueduct Trailway state park, and the South County Trailway county park

- Sugar Pond, a small pond located in the Riverview Manor portion of the Hillside Woods; open to ice skating in the winter

- Numerous playing fields including the Burke Estate, Zinsser Park, Reynolds Field, and Uniontown Field

- Downtown Hastings-on-Hudson, with retail stores and restaurants

- Ever Rest, the homestead and studio of painter Jasper Cropsey (1823–1900), listed on the National Register of Historic Places in New York.

- A public library

- A farmer's market on Saturdays (outdoors June–November; indoors twice monthly December–May)

- The VFW building with a dance studio and karate school

- Hastings High School, which presents theatre productions and other shows

- "Museum of the Streets", a walking tour with historic markers maintained by the Hastings Historical Society.[14]

- A new free outdoor Concert Series was launched at MacEachron Waterfront Park in 2018.

- The River Spirit Music and Arts Festival, the Village's annual event, at Draper Park, on the second Saturday of September.

Notable people

- Steve Addabbo, Grammy winner

- Marco Arment, creator of Instapaper and co-founder of Tumblr

- Edoardo Ballerini, actor, audiobook narrator

- Helen Barolini, author

- Michael Brecker, jazz saxophonist and composer

- Billie Burke, actress best known for playing the Good Witch of the North in The Wizard of Oz

- Daniel Callahan, medical ethicist, co-founder, Hastings Center

- Kenneth B. Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark, influential civil rights pioneers and psychologist

- Stephen Collins, actor

- Jasper Francis Cropsey, painter

- Albert Dekker, actor

- Crescent Dragonwagon, novelist, children's book writer, cookbook author; daughter of Maurice Zolotow and Charlotte Zolotow

- Henry Draper, astronomer and author; first to discover that oxygen is present in the sun

- John W. Draper, first president of American Chemical Society between 1876 and 1877

- Adrian Ettlinger, inventor and engineer

- David Farragut, American Civil War Admiral

- Martin Gardner, author of the "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American

- Giuseppe Garibaldi, key figure in Italian unification

- Marcia Mitzman Gaven, actress and Tony Award nominee 1993

- Willard Gaylin, co-founder, Hastings Center, psychiatrist and medical ethicist

- Seth Godin, entrepreneur, author and public speaker

- Benjamin Franklin Goodrich, founder of Goodrich Corporation[15]

- Zack O'Malley Greenburg, author and former child actor

- Harry Hillman, 1904 Olympic gold medalist in the 400m, 200mH, & 400mH. Silver medalist in 1908 in the 400mH.

- Lewis Hine, photographer

- Stephen Horelick, composer of Reading Rainbow, among many other music credits.

- James Howe, children's book author, author of Bunnicula and The Misfits, among many other books.

- James Kaplan, author of Two Guys from Verona, Dean and Me: A Love Story, Frank:The Voice, and other books.

- Eric Kuhn, theater producer and media executive

- Ricki Lake, actress and television talk show host

- John Lavachielli, actor

- David Leonhardt, Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the New York Times

- Barron H. Lerner, internist, medical historian and ethicist, professor of medicine. Author of "The Good Doctor," "When Illness Goes Public," and other books.

- Jacques Lipchitz, sculptor

- Steven Lysak, 1948 Olympic gold medalist in canoeing

- Ali Marpet, American football player in the NFL

- Antonia Maury, astronomer

- Abel Meeropol, writer; under his pseudonym Lewis Allan wrote the anti-lynching poem Strange Fruit

- Robert Meeropol, son of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, who were executed for conspiracy to commit espionage

- Robert C. Merton, 1997 winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics

- Robert K. Merton, sociologist and creator of popular concepts including "self-fulfilling prophecy", "role model", "unintended consequences", and "anomie"

- Frank Morgan, character actor, played title character in the film The Wizard of Oz

- George Newall, co-creator, composer, executive producer for the children's educational television series, "School House Rock"

- Adolph S. Ochs, New York Times and Chattanooga Times publisher

- Keith Olbermann, news anchor, liberal commentator and radio sportscaster[16]

- Jan Owen, book artist

- John Patitucci, jazz bass player, specializing in post-bop, jazz fusion and Brazilian jazz

- Edmund Phelps, Columbia University professor and winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics

- Leo James Rainwater, Nobel Prize-winning physicist

- Molly Ringwald, actress

- John Riordan, Bell Labs mathematician

- Coco Rocha, model

- J.T. Rogers, playwright

- Margaret Sanger, founder of the American Birth Control League

- John Saunders, ESPN[17]

- Alan Schneider, Broadway director

- Cathy Seibel, United States federal judge for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, appointed in 2008.

- William Shatner, actor[18]

- Richmond Shreve, architect, Empire State Building

- Charles Siebert, actor/director

- Jerry Silverman, guitarist, folk singer, teacher, publisher guitar music books

- Gary Smulyan, jazz baritone saxophonist

- André Leon Talley, editor-at-large of American Vogue Magazine

- Max Theiler, Nobel Prize laureate

- John Bartholomew Tucker, radio and television personality, as well as an author.

- Howard Van Hyning (1936–2010), percussionist with the New York City Opera[19]

- William Vickrey, Columbia University professor, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics

- Charles Webb, novelist, most notably of The Graduate

- Phideaux Xavier, progressive rock musician

- Ed Young, children's book author and illustrator

- Florenz Ziegfeld, Broadway impresario of theatrical spectaculars including the Ziegfeld Follies

- Charlotte Zolotow, children's book author and editor

- Maurice Zolotow, Hollywood biographer; author of first biography of Marilyn Monroe

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2017 ACS 5-year population essay: Hastings-on-Hudson village, Westchester County, New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Hastings History Archived January 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Hal Borland (December 17, 1939). "Pioneers in Mental Health Expand Program; Hillside Hospital to Build New Plant to Carry on Modern Methods". The New York Times.

- "Hillside Hospital Welcomes to City; $700,000 Institution Formerly in Westchester Opened on Site in Queens". The New York Times. October 20, 1941.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Alex Williams (February 15, 2013). "Creating Hipsturbia". The New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- Velsey, Kim (February 19, 2013). "Same As It Ever Was: Hipsters Move to the Suburbs, Fancy Themselves Pioneers". New York Observer. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Foster, Brooke Lea (2018). "Comparing Suburbs: Montclair in New Jersey vs. Dobbs Ferry in New York". The New York Times.

- "Museum in the Streets". Hastings Historical Society. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Benjamin F. Goodrich". NNDB. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- Q&A with Keith Olbermann, 12 March 2006. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- CampaignMoney.com

- Shatner, William; David Fisher (28 April 2009). Up Till Now: The Autobiography. p. 60. ISBN 9781429937979. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- Fox, Margalit. "Howard Van Hyning, Percussionist and Gong Enthusiast, Dies at 74", The New York Times, November 8, 2010. Accessed November 9, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. |