Hispanos of New Mexico

The Hispanos of New Mexico, also known as Neomexicanos (Spanish: Neomexicano),[2] or "Nuevomexicanos" are an ethnic group primarily residing in the U.S. state of New Mexico, as well as the southern portion of Colorado. They are typically variously of Iberian, Criollo Spaniard, Mestizo, and Genízaro heritage, and are descended from Spanish-speaking settlers of the historical region of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, which makes up the present day U.S. states of New Mexico (Nuevo México), southern Colorado, and parts of Arizona, Texas, and Utah. Neomexicanos speak New Mexican English, Neomexicano Spanish, or both bilingually, and identify with the culture of New Mexico displaying patriotism in regional Americana, pride for various cities and towns such as Albuquerque or Santa Fe, and expressing through New Mexican cuisine and New Mexico music, as well as in Ranchero and U.S. Route 66 cruising lifestyles.[3] Alongside Californios and Tejanos, they are part of the larger Hispano communities of the United States, which have lived in the American Southwest since the 16th century or earlier (since many individuals are from mestizo communities, and thus, also of indigenous descent). The descendants of these culturally mixed communities make up an ethnic community of more than 340,000 in New Mexico, with others in southern Colorado.

Hispanos identify strongly with their Spanish heritage although many also have varying levels of Apache, Comanche, Pueblo, Navajo, Native Mexican, and Genízaro ancestry.[4] Exact numbers for the population size of New Mexican Hispanos is difficult, as many also identify with Chicano and Mexican-American movements.[5] For most of its modern history, New Mexico existed on the periphery of the Spanish empire from 1598 until 1821 and later Mexico (1821–1848), but was dominated by Comancheria politically and economically from the 1750s to 1850s. Due to the Comanche, contact with the rest of Spanish America was limited, and New Mexican Spanish developed closer trading links with the Comanche than the rest of New Spain. In the meantime, some Spanish colonists coexisted with and intermarried with Puebloan peoples and Navajos, enemies of the Comanche.[6] New Mexicans of all ethnicities were commonly enslaved by the Comanche and Apache of Apacheria, while Native New Mexicans were commonly enslaved and adopted Spanish language and culture. These Genízaros served as house servants, sheep herders, and in other capacities in New Mexico including what is known today as Southern Colorado well into the 1800s. By the late 18th century, Genízaros and their descendants, often referred to as Coyotes, comprised nearly one-third of the entire population of New Mexico.[7][8] After the Mexican–American War, New Mexico and all its inhabitants came under the governance of the English-speaking United States, and for the next hundred years, English-speakers increased in number. By the 1980s, more and more Hispanos were using English instead of New Mexican Spanish at home.[3][9]

Term

In New Mexico, the predominant term for this ethnic group has always been hispano, analogous to californio and tejano. In New Mexico, the Spanish-speaking population (of colonial descent) was always proportionally greater than those of California and Texas. The term is commonly used to differentiate those who settled the area early, around 1598 to 1848, from later Mexican migrants. It can also refer to anyone of "Spanish or Indo-Hispanic descent native to the American Southwest."[3] Since the spread of the terms Hispanic and Latino since 1970 to encompass all peoples in the United States (and often beyond) of Spanish-speaking background, the terms Nuevomexicanos, Novomexicanos, and Neomexicanos are sometimes used in English to refer to this group, but this is less common in New Mexico.

History

Spanish governance

The first Spanish settlers emigrated to New Mexico on July 11, 1598, when the explorer Don Juan de Oñate came north from Mexico City to New Mexico with 500 Spanish settlers and soldiers and a livestock of 7,000 animals. The settlers founded San Juan de los Caballeros, the first Spanish settlement in what was called the Kingdom of New Mexico, after the Valley of Mexico.[10]

Oñate also conquered the territories of the Pueblo peoples. He became the first governor of New Mexico. The exploitation of Spanish rule under Oñate caused nearly continuous attacks and reprisals from the nomadic Amer-Indian tribes on the borders, especially the Apache, Navajo, and Comanche peoples. There were also major clashes between the Franciscan missionaries (brought to New Mexico to convert the indigenous peoples to Christianity and Hispanicize them) and secular and religious authorities. The colonists exploited Indian labor, as was typical in other areas of the Spanish colonies in the Americas.

In the 1650s, Governor Bernardo López de Mendizabal, and his subordinate Nicolas de Aguilar, enacted a law to force the settlers and Franciscans to pay Native Americans for their work. He opposed what he perceived to be the mistreatment of the Indians by the Franciscans and proposed to allow the Indians to preserve and to practice their culture, religion, and customs. The Franciscans protested the law and accused the governor before the Inquisition. Later he was tried in Mexico City. So, the Franciscans indirectly governed the New Mexico province.

In 1680, the Native American groups that lived along the Rio Grande successfully rose against the Spanish colonizers in what became known as the Pueblo Revolt. When the Spanish returned to the province in 1692, Don Diego de Vargas became the new governor of New Mexico. He entered the former capital bearing an image of La Conquistadora. The Native Americans were so intrigued by the statue of the Virgin Mary that they are reputed to have laid down their arms at the sight of it. This Reconquista of New Mexico is reputed to have been bloodless and every year since then this statue of the Virgin Mary has been carried in procession through the City of Santa Fe to commemorate the event.

At the time of Vargas's arrival, New Mexico was under the jurisdiction of the Royal Audiencia of Guadalajara and belonged to the Viceroyalty of New Spain. However, in 1777 with the creation of the Provincias Internas it was included only in the jurisdiction of the Commandant-General. After the revolt, the Spanish issued substantial land grants to each Pueblo Amerindian and appointed a public defender to protect the rights of the Indians and to argue their legal cases in the Spanish courts.

Mexican governance

The mainland part of New Spain won independence from Spain in 1821, and New Mexico became part of the new nation of Mexico. The Spanish settlers of New Mexico, and their descendants, adapted somewhat to Mexican citizenship. The Hispanos choose to make New Mexico a territory of Mexico, rather than a state, in order to have more local control over its affairs. In 1836, after the Republic of Texas gained independence, Texas claimed part of the Province of New Mexico which was disputed by Mexico. In 1841, the Texians sent an expedition to occupy the area, but it was captured by Mexican troops.[11]

The Revolt of 1837 in New Mexico caused the Hispanos to overthrow and execute the centrally appointed Mexican governor, demanding increased regional authority. This revolt was defeated by Manuel Armijo, a fellow Hispano appointed by Mexico, which eased the people's concerns. The impetus for this revolt was the class antagonism present in New Mexican society. When central rule was reestablished, Armijo ruled the province as governor, though with greater autonomy. In the mid-1830s, New Mexico began to function as a trading hub between the United States, Central Mexico, and Mexican California.

New Mexico grew economically and the United States began to take notice of the strategic position New Mexico played in the western trade routes. In 1846, during the Mexican–American War, the United States Army occupied the province, which caused the Taos Revolt a popular insurrection in January 1847 by Hispanos and Pueblo allies against the occupation. In two short campaigns, U.S. troops and militia crushed the rebellion. The rebels regrouped and fought three more engagements, but after being defeated, they abandoned open warfare. Mexico ceded the territories of the north to the United States with the so-called Mexican Cession. As a result, Texas gained control of the City of El Paso, which was formerly in New Mexico. However, in the Compromise of 1850 Texas gave up its claim to the other areas of New Mexico.

United States governance

The New Mexico Territory played a role in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. Both Confederate and Union governments claimed ownership and territorial rights over it. In 1861 the Confederacy claimed the southern tract as its own Arizona Territory and waged the ambitious New Mexico Campaign in an attempt to control the American Southwest and to open up access to Union California. Confederate power in the New Mexico Territory was effectively broken in 1862 after the Battle of Glorieta Pass. The New Mexico Volunteer Infantry, with 157 Hispanic officers, was the Union unit with the most officers of that ethnic background. Along with Colonel Miguel E. Pino and Lieutenant Colonel Jose Maria Valdez, who belonged to the 2nd New Mexico Volunteer Infantry, the New Mexico Volunteer Infantry also included Colonel Diego Archuleta (eventually promoted to Brigadier General), the commanding officer of the First New Mexico Volunteer Infantry, Colonel Jose G. Gallegos commander of the Third New Mexico Volunteer Infantry, and Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Perea, who commanded Perea's Militia Battalion.[12]

After the Mexican–American War, Anglo Americans began migrating in large numbers to all of the newly acquired territory. Anglos began taking lands from both Native Americans and Hispanos by different means, most notably by squatting. Squatters often sold these lands to land speculators for huge profits, especially after the passing of the 1862 Homestead Act. Hispanos demanded that their lands be returned but governments did not respond favorably. For example, the Surveyor of General Claims Office in New Mexico would at times take up to fifty years to process a claim, meanwhile, the lands were being grabbed up by the newcomers. One tactic used to defraud Hispanos from their lands was to demand that they present documentation proving ownership written in English. Because the territory had previously been part of Mexico, only Spanish language ownership documentation existed. While the Santa Fe, Atchison, and Topeka railroad was built in the 1890s, speculators known as the Santa Fe Ring, orchestrated schemes to remove natives from their lands. In response, Hispanos gathered to reclaim lands taken by Anglos.[13] Hoping to scare off the new immigrants, they eventually used intimidation and raids to accomplish their goals. They sought to develop a class-based consciousness among local people through the everyday tactics of resistance to the economic and social order confronting common property land grant communities. They called themselves Las Gorras Blancas a term owing its origin to the white head coverings many wore.

In January 1912, New Mexico became an American state, and Anglophones eventually became the majority population. The state's Hispanos became an economically disadvantaged population, becoming virtual second-class citizens compared to the Anglos. The Hispanos suffered discrimination from Anglophone Americans, who also questioned the loyalty of these new American citizens. The cultures of Hispanos and immigrant Anglophones eventually mixed to some degree, as was the case with immigrants in other parts of the United States.[14][15]

The United States and the New Mexico State governments tried to incorporate the Hispanos into mainstream American life. Examples of this include: is the mixing of Hispanos' images with American patriots' symbols, the first translation of the national anthem into Spanish, and the recruitment of numerous Hispanos ranchers, horsemen, and farmers to fight for the U.S. in both the Spanish American and First World wars. One early contribution by the Hispanos to American society was their support for women's suffrage. Contributions from both sides helped to improve the conditions of citizenship in the community, but social inequality between the Anglos and Hispanos remained.[14][15]

Anglos and Hispanics cooperated because both prosperous and poor Hispanics could vote and they outnumbered the Anglos. Around 1920, the term "Spanish-American" replaced "Mexican" in polite society and in political debate. The new term served the interests of both groups. For Spanish speakers, it evoked Spain, not Mexico, recalling images of a romantic colonial past and suggesting a future of equality in Anglo-dominated America. For Anglos, on the other hand, it was a useful term that upgraded the state's image, for the old image as a "Mexican" land suggested violence and disorder, and had discouraged capital investment and set back the statehood campaign. The new term gave the impression that Spanish-Americans belonged to a true American political culture, making the established order appear all the more democratic.[16]

Population

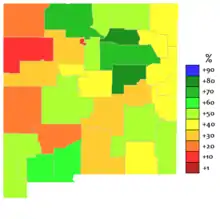

Currently, the majority of the Hispano population is distributed between New Mexico and Southern Colorado, although other southwestern states have thousands of Hispanos with origins in New Mexico. Most of New Mexico's Hispanos, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, live in the northern half of the state, mainly Santa Fe, Taos, and Española, although they are distributed throughout the north of the state. Also there communities in the Albuquerque metro and basin, in mountain ranges like the Sangre de Cristo, Sandia–Manzano, Mogollon, and Jemez, and along river valleys statewide such as Mimbres, San Juan, and Mesilla.

The Hispano community in Southern Colorado is descended from Hispanos from New Mexico who migrated there in the early 19th century. Several Hispano ethnographers, linguists, and folklorists studied both of these centers of population (particularly Rubén Cobos, Juan Bautista Rael and Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Sr.).

Crypto-Judaism

According to the Kupersmit Research, in 2015 there were about 24,000 Jews in New Mexico, 1,700 of whom were born in the state.[17] Some researchers and historians believe that number would rise considerably if Anusim (or Crypto-Jews) were included in those estimates.

In Old Town Albuquerque, the San Felipe de Neri Church, built in 1793, contains a Star of David on the left and right sides of the altar. Some observers believe that this is evidence of the influence of Crypto-Jews in New Mexico, but others think there is not enough to support that interpretation. Researchers have found cemetery headstones in Northern New Mexico with Hebrew and Jewish symbols alongside those with Catholic crosses.[18] Since their maternal lines were not Jewish and they have not maintained Jewish practices, they would not meet requirements of Orthodox Judaism's halakha, but possibly would under Reconstructionist and Reform Judaism.

Genetic studies have been conducted on some Spanish New Mexicans. Michael Hammer, a research professor at the University of Arizona and an expert on Jewish genetics, said that fewer than 1% of non-Semites, but more than four times the entire Jewish population of the world, possessed the male-specific "Cohanim marker" (this is not carried by all Jews, but is prevalent among Jews claiming descent from hereditary priests). Some 30 of 78 Hispanos tested in New Mexico (38.5%) were found to carry the Cohanim marker.

Bennett Greenspan, Family Tree DNA’s founder, whose recent ancestors were Ashkenazi Jews in Eastern Europe, also carries a Sephardic Y-chromosomal lineage, belonging to haplogroup J-M267. Greenspan's 67-marker STR matches include two Hispanic descendants of Juan Tenorio of Seville, Spain, one of whom is Manuel Tenorio, a Catholic from a New Mexican Hispano family. Other Y-DNA testing of Hispanic populations revealed between 10% and 15% of men living in New Mexico, south Texas and northern Mexico have a Y chromosome that can be traced to the Middle East.

New Mexican Hispanos have been found to share identical by descent autosomal DNA segments with Ashkenazi Jews, Syrian Jews, and Moroccan Jews in GEDmatch. However, Hispanos of New Mexico have no more Sephardic Jewish genes than the Hispanic American population.[19]

New Mexican families

The following family names are listed in the New Mexico Office of the State Historian,[20] Origins of New Mexico Families by Fray Angélico Chávez, and Beyond Origins of New Mexico Families by José Antonio Esquibel.[21]

- Abendaño

- Abeyta

- Alderete

- Alire

- Anaya Almazán

- Apodaca

- Aragón

- Archibeque

- Archuleta

- Arellano

- Armijo

- Atencio

- Baca

- Benavides

- Borrego

- Bustamante

- Bustos/Bustillos

- Candelaria

- Casados

- Cedillo Rico de Rojas

- Chávez

- Cisneros

- Córdova

- Domínguez de Mendoza

- Durán

- Durán y Chaves

- Encinias

- Esquibel

- Espinosa

- Gallegos

- Gabaldón

- García

- García Jurado

- Gómez

- González

- Griego

- Guadalajara

- Gurulé

- Gutiérrez

- Herrera

- Jaramillo Negrete

- Jirón de Tejeda

- Jorge de Vera

- Jurdo de Gracia

- Leyva

- Lobato/Lovato

- López

- López de Ocanto

- López del Castillo

- López de Gracia

- López Holguín

- López Sambrano

- Lucero

- Lucero de Godoy

- Luján

- Luna

- Madrid

- Mirabal

- Maese

- Manzanares

- Martinez

- Márquez

- Martín Serrano

- Mascareñas

- Medina

- Mestas

- Montes Vigil

- Miera y Pacheco

- Molina

- Mondragón

- Moreno de Trujillo

- Montaño

- Montoya

- Moraga

- Moya

- Naranjo

- Nieto

- Olivas

- Ortega

- Ortíz

- Páes Hurtado

- Pacheco

- Padilla

- Paredes

- Pérez de Bustillo

- Peña

- Pino

- Quintana

- Rael de Aguilar

- Rivera

- Robledo

- Rodríguez

- Romero

- Romo de Vera

- Roybal

- Roybal y Torrado

- Sáez/Sáenz

- Sandoval Martínez

- Salas

- Salazar

- Sánchez

- Sánchez de Iñigo

- Santisteban

- Sedillo

- Segura

- Sena

- Serna

- Silva

- Sisneros

- Solano

- Tafoya

- Telles Jirón

- Tapia

- Tenorio

- Torrado

- Torres/Torrez

- Trujillo

- Ulibarrí

- Vásquez de Lara

- Valdes

- Varela

- Vallejos

- Valles

- Vega y Coca

- Velásquez

- Vera

- Vigil

- Vitoria Carvajal

- Villalpando

- Zamorano

New Mexican Spanish

It is commonly thought that Spanish is an official language alongside English because of its wide usage and legal promotion of Spanish in New Mexico; however, the state has no official language. New Mexico's laws are promulgated bilingually in Spanish and English. Although English is the state government's paper working language, government business is often conducted in Spanish, particularly at the local level. The original state constitution of 1912, renewed in 1931 and 1943, provided for a bilingual government with laws being published in both languages.[22][23] The constitution does not identify any language as official.[24] While the legislature permitted the use of Spanish there until 1935, in the 21st century all state officials are required to be fluent in English. Some scholars argue that, since not all legal matters are published in both languages, New Mexico cannot be considered a true bilingual state.[23] Juan Perea has countered with saying that the state was officially bilingual until 1953.[25]

With regard to the judiciary, witnesses have the right to testify in either of the two languages. Monolingual speakers of Spanish have the same right and obligation to be considered for jury duty as do speakers of English.[24][26] In public education, the state has the constitutional obligation to provide for bilingual education and Spanish-speaking instructors in school districts where the majority of students are hispanophone.[24]

In 1995, the state adopted a State Bilingual Song, "New Mexico – Mi Lindo Nuevo México".[27]:75,81

Because of the relative isolation of these people from other Spanish-speaking areas over most of the area's 400-year history, they developed what is known as New Mexico Spanish. In particular the Spanish of Hispanos in Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado has retained many elements of 16th- and 17th-century Spanish spoken by the colonists who settled the area. In addition, some unique vocabulary has developed here.[3] New Mexican Spanish also contains loan words from the Puebloan languages of the upper Rio Grande Valley, Mexican-Spanish words (mexicanismos), and borrowings from English.[3] Grammatical changes include the loss of the second person plural verb form, changes in verb endings, particularly in the preterite, and partial merging of the second and third conjugations.[28]

Notable people

| Lists of Americans |

|---|

| By U.S. state |

| By ethnicity or nationality |

|

|

- Santiago Abreú (died 8 August 1837) governor of Santa Fe de Nuevo México from 1832 to 1833

- Nicolas de Aguilar

- Jose Ramon Aguilar (1852-1929) Pioneer rancher. Aguilar, CO is named for him.

- Juan Bautista Vigil y Alarid - (1792–1866) Governor of New Mexico in 1846

- Rudolfo Anaya

- Antonio D. Archuleta State Senator. In 1883 introduced the bill to create Archuleta County from the western portion of Conejos County.

- Manuel Armijo - (ca. 1793–1853) Three times as governor of New Mexico.

- Bartolomé Baca (c. 1767 – 1834) Governor of Santa Fe de Nuevo México

- Polly Baca

- Felipe Baca (1828–1874) Pioneer rancher. Helped found Trinidad, CO. Baca County is named for him.

- Ezequiel Cabeza De Baca – (1864–1917) was the first Hispano elected for office as Lieutenant Governor in New Mexico's first election. He is a descendant of the original Spanish settlers which later became part of the Baca Family of New Mexico.

- Casimiro Barela (1847–1920) Helped write Colorado’s State Constitution.

- José Francisco Chaves

- Manuel Antonio Chaves (1818? – 1889), known as El Leoncito (the little lion), was a soldier in the Mexican Army.

- Angelico Chavez

- Denise Chavez

- Dennis Chavez – (1888–1962) Democratic U.S. Senator from the State of New Mexico.

- Linda Chavez – father's family came to New Mexico from Spain in 1601.[29]

- Julian A. Chavez

- Francisco Xavier Chávez - (1768-1838) Governor of Mexican New Mexico in 1822.

- Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Sr. - (1880–1958). Professor who studied the Spanish American folklore and philology. He descended of the first New Mexicans to settle in Colorado in the mid-1800s.

- Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Jr., (1907 – 2004), son of Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Sr. Professor at Stanford University and an expert on Spanish linguistics, focusing on Spanish American folklore.

- José Manuel Gallegos

- Demi Lovato, multi-platinum selling recording artist and actress

- Ben R. Lujan, US Congressman

- Manuel Lujan, Former US Congressman, Secretary of the Interior

- Michelle Lujan Grisham, Current Governor of New Mexico

- Tranquilino Luna

- Francisco Antonio Manzanares

- Antonio José Martínez – (1793–1867) priest, educator, publisher, rancher, farmer, community leader, and politician

- Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco

- Joseph Montoya – (1915–1978) Democratic U.S. Senator from New Mexico.

- Miguel Antonio Otero (born 1829) – Spanish politician of the New Mexico Territory.

- Miguel Antonio Otero (born 1859) – Governor of New Mexico Territory (1897–1906).

- Adelina Ortero-Warren (born 1881) - Politician and Suffragist

- Mariano S. Otero (1844–1904) – delegate from the Territory of New Mexico.

- Francisco Perea

- Pedro Perea

- Juan Bautista Rael – (1900–1993) ethnographer, linguist, and folklorist who was a pioneer in the study of the Hispanos; he studied the peoples, their stories and language, from Northern both New Mexico and Southern Colorado.

- Edward L. Romero

- Trinidad Romero

- Edward R. Roybal

- John Salazar

- Ken Salazar

- Manuel de Sandoval - (18th century) prominent military man and the governor of Coahuila (1729–1733 ) and Texas (1734–1736)

- Diego Sanchez

- Henry Cisneros

- Raymond Telles Jr. (September 5, 1915 – March 8, 2013) was the first Mexican-American Mayor of a major American city, El Paso, Texas.[1] He was also the first Hispanic appointed as a U.S. ambassador.

See also

References

- Hordes, Stanley M. (2005). To The End of The Earth: A History of the Crypto-Jews of New Mexico. Columbia University Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-231-12937-4.

- Gutiérrez, R.A.; Padilla, G.M.; Herrera-Sobek, M. (1993). Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage. Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage Project publication. Arte Público Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-1-55885-251-8. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Cobos, Rubén (2003) "Introduction," A Dictionary of New Mexico & Southern Colorado Spanish (2nd ed.); Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press; p. ix; ISBN 0-89013-452-9

- Wasniewski, M.A.; Kowalewski, A.; O'Hara, L.T.; Rucker, T. (2014). Hispanic Americans in Congress, 1822-2012. House document. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-16-092028-8. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Castro, R. (2001). Chicano Folklore: A Guide to the Folktales, Traditions, Rituals and Religious Practices of Mexican Americans. OUP USA. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-19-514639-4. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- House Memorial 40 (HM40), "Genizaros, In Recognition," 2007 New Mexico State Legislature, Regular Session.

- Senate Memorial 59 (SM59), "Genizaros, In Recognition," 2007 New Mexico State Legislature, Regular Session.

- "Indian Slavery Once Thrived in New Mexico. Latinos Are Finding Family Ties to It". The New York Times. January 28, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Simmons, Marc, The Last Conquistador, Norman: U of OK Press, 1992, pp. 96, 111

- Carroll, H. Bailey. "Texan Santa Fe Expedition". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- MILITARY ORDER OF THE LOYAL LEGION OF THE UNITED STATES

- Rosales, F. Arturo Chicano: The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement (Houston, TX: Arte Publico Press, 1997) p. 7-9

- Phillip Gonzales and Ann Massmann, "Loyalty Questioned: Neomexicanos in the Great War." Pacific Historical Review, Nov 2006, Vol. 75 Issue 4, pp 629–666

- Phillip B. Gonzales, "Spanish Heritage and Ethnic Protest in New Mexico: The Anti-Fraternity Bill of 1933," New Mexico Historical Review, Fall 1986, Vol. 61 Issue 4, pp 281–299

- Charles Montgomery, "Becoming 'Spanish-American': Race and Rhetoric in New Mexico Politics, 1880-1928," Journal of American Ethnic History, Summer 2001, Vol. 20 Issue 4, p59-84

- Uyttebrouck, Olivier (October 1, 2013). "Study estimates 24,000 Jews living in NM". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- Halevy, Schulamith C. (2009). Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico (PDF). Hebrew University.

- I. King Jordan,Lavanya Rishishwar,Andrew B. Conley (2019). "Native American admixture recapitulates population-specific migration and settlement of the continental United States". Plos Genetics. Retrieved 2020-08-04.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Genealogy". New Mexico Office of the State Historian. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Maldonado, G. (2014). MALDONADO JOURNEY to the KINGDOM of NEW MEXICO. Trafford Publishing. p. 531. ISBN 978-1-4907-3952-6. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Crawford, John (1992). Language loyalties: a source book on the official English controversy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 62.

- Cobarrubias, Juan; Fishman, Joshua A (1983). Progress in Language Planning: International Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter. p. 195.

- Constitution of the State of New Mexico. Archived 2014-01-02 at the Wayback Machine Adopted January 21, 1911.

- Perea, Juan F. Los Olvidados: On the Making of Invisible People. New York University Law Review. 70. pp. 965–990.

- Roberts, Calvin A. (2006). Our New Mexico: A Twentieth Century History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 23.

- "State Symbols". New Mexico Blue Book 2007–2008. New Mexico Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- Cobos, Rubén, op. cit., pp. x-xi.

- Conservative and Hispanic, Linda Chavez Carves Out Leadership Niche