Labrador Sea

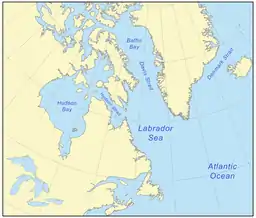

The Labrador Sea (French: mer du Labrador, Danish: Labradorhavet) is an arm of the North Atlantic Ocean between the Labrador Peninsula and Greenland. The sea is flanked by continental shelves to the southwest, northwest, and northeast. It connects to the north with Baffin Bay through the Davis Strait.[3] It has been described as a marginal sea of the Atlantic.[4][5]

| Labrador Sea | |

|---|---|

Past sunset at Labrador Sea, off the coast of Paamiut, Greenland | |

Labrador Sea | |

| |

| Coordinates | 61°N 56°W |

| Type | Sea |

| Basin countries | Canada and Greenland |

| Max. length | c. 1,000 km (621 mi) |

| Max. width | c. 900 km (559 mi) |

| Surface area | 841,000 km2 (324,700 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 1,898 m (6,227 ft) |

| Max. depth | 4,316 m (14,160 ft) |

| References | [1][2] |

The sea formed upon separation of the North American Plate and Greenland Plate that started about 60 million years ago and stopped about 40 million years ago. It contains one of the world's largest turbidity current channel systems, the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel (NAMOC), that runs for thousands of kilometers along the sea bottom toward the Atlantic Ocean.

The Labrador Sea is a major source of the North Atlantic Deep Water, a cold water mass that flows at great depth along the western edge of the North Atlantic, spreading out to form the largest identifiable water mass in the World Ocean.

History

The Labrador Sea formed upon separation of the North American Plate and Greenland Plate that started about 60 million years ago (Paleocene) and stopped about 40 million years ago.[2] A sedimentary basin, which is now buried under the continental shelves, formed during the Cretaceous.[2] Onset of magmatic sea-floor spreading was accompanied by volcanic eruptions of picrites and basalts in the Paleocene at the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay.[2]

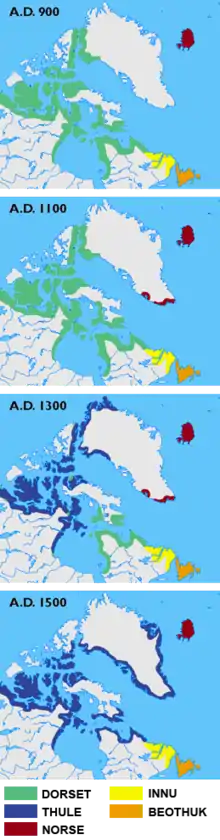

Between about 500 BC and 1300 AD, the southern coast of the sea contained Dorset, Beothuk and Inuit settlements; Dorset tribes were later replaced by Thule people.[6]

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Labrador Sea as follows:[7]

On the North: the South limit of Davis Strait [The parallel of 60° North between Greenland and Labrador].

On the East: a line from Cape St. Francis 47°45′N 52°27′W (Newfoundland) to Cape Farewell (Greenland).

On the West: the East Coast of Labrador and Newfoundland and the Northeast limit of the Gulf of St. Lawrence – a line running from Cape Bauld (North point of Kirpon Island, 51°40′N 55°25′W) to the East extreme of Belle Isle and on to the Northeast Ledge (52°02′N 55°15′W). Thence a line joining this ledge with the East extreme of Cape St. Charles (52°13'N) in Labrador.

Oceanography

The Labrador Sea is about 3,400 m (1,859 fathoms; 11,155 feet) deep and 1,000 km (621 miles; 540 nautical miles) wide where it joins the Atlantic Ocean. It becomes shallower, to less than 700 m (383 fathoms; 2,297 ft) towards Baffin Bay (see depth map) and passes into the 300 km (190 mi; 160 nmi) wide Davis Strait.[2] A 100–200 m (55–109 fathoms; 330–660 ft) deep turbidity current channel system, which is about 2–5 km (1.2–3.1 mi; 1.1–2.7 nmi) wide and 3,800 km (2,400 mi; 2,100 nmi) long, runs on the bottom of the sea, near its center from the Hudson Strait into the Atlantic.[8][9] It is called the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel (NAMOC) and is one of the world's longest drainage systems of Pleistocene age.[10] It appears as a submarine river bed with numerous tributaries and is maintained by high-density turbidity currents flowing within the levees.[11]

The water temperature varies between −1 °C (30 °F) in winter and 5–6 °C (41–43 °F) in summer. The salinity is relatively low, at 31–34.9 parts per thousand. Two-thirds of the sea is covered in ice in winter. Tides are semi-diurnal (i.e. occur twice a day), reaching 4 m (2.2 fathoms; 13 ft).[1]

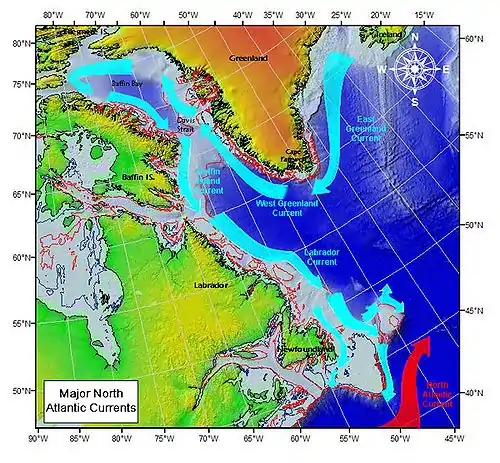

There is an anticlockwise water circulation in the sea. It is initiated by the East Greenland Current and continued by the West Greenland Current, which brings warmer, more saline waters northwards, along the Greenland coasts up to the Baffin Bay. Then, the Baffin Island Current and Labrador Current transport cold and less saline water southward along the Canadian coast. These currents carry numerous icebergs and therefore hinder navigation and exploration of the gas fields beneath the sea bed.[3][12] The speed of the Labrador current is typically 0.3–0.5 m/s (0.98–1.64 ft/s), but can reach 1 m/s (3.3 ft/s) in some areas,[13] whereas the Baffin Current is somewhat slower at about 0.2 m/s (0.66 ft/s).[14] The Labrador Current maintains the water temperature at 0 °C (32 °F) and salinity between 30 and 34 parts per thousand.[15]

The sea provides a significant part of the North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) – a cold water mass that flows at great depth along the western edge of the North Atlantic, spreading out to form the largest identifiable water mass in the World Ocean.[16] The NADW consists of three parts of different origin and salinity, and the top one, the Labrador Sea Water (LSW), is formed in the Labrador Sea. This part occurs at a medium depth and has a relatively low salinity (34.84–34.89 parts per thousand), low temperature (3.3–3.4 °C (37.9–38.1 °F)) and high oxygen content compared to the layers above and below it. LSW also has a relatively low vorticity, i.e. the tendency to form vortices, than any other water in North Atlantic that reflects its high homogeneity. It has a potential density of 27.76–27.78 mg/cm3 relatively to the surface layers, meaning it is denser, and thus sinks under the surface and remains homogeneous and unaffected by the surface fluctuations.[17]

Fauna

The northern and western parts of the Labrador Sea are covered in ice between December and June. The drift ice serves as a breeding ground for seals in early spring. The sea is also a feeding ground for Atlantic salmon and several marine mammal species. Shrimp fisheries began in 1978 and intensified toward 2000, as well as cod fishing. However, the cod fishing rapidly depleted the fish population in the 1990s near the Labrador and West Greenland banks and was therefore halted in 1992.[12] Other fishery targets include haddock, Atlantic herring, lobster and several species of flatfish and pelagic fish such as sand lance and capelin. They are most abundant in the southern parts of the sea.[18]

Beluga whales, while abundant to the north, in the Baffin Bay, where their population reaches 20,000, are rare in the Labrador Sea, especially since the 1950s.[19] The sea contains one of the two major stocks of Sei whales, the other one being the Scotian Shelf. Also common are minke and bottlenose whales.[20]

The Labrador duck was a common bird on the Canadian coast until the 19th century, but is now extinct.[21] Other coastal animals include the Labrador wolf (Canis lupus labradorius),[22][23] caribou (Rangifer spp.), moose (Alces alces), black bear (Ursus americanus), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), Arctic fox (Alopex lagopus), wolverine, snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), grouse (Dendragapus spp.), osprey (Pandion haliaetus), raven (Corvus corax), ducks, geese, partridge and American wild pheasant.[24][25]

Flora

Coastal vegetation includes black spruce (Picea mariana), tamarack, white spruce (P. glauca), dwarf birch (Betula spp.), aspen, willow (Salix spp.), ericaceous shrubs (Ericaceae), cottongrass (Eriophorum spp.), sedge (Carex spp.), lichens and moss.[25] Evergreen bushes of Labrador tea, which is used to make herbal teas, are common in the area, both on the Greenland and Canadian coasts.[26]

References

- "Labrador" (in Russian). Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- Wilson, R. C. L; London, Geological Society of (2001). "Non-volcanic rifting of continental margins: a comparison of evidence from land and sea". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 187: 77. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.187...77C. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.187.01.05. ISBN 978-1-86239-091-1. S2CID 140632779.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Labrador Sea". Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- Calow, Peter (12 July 1999). Blackwell's concise encyclopedia of environmental management. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-632-04951-6. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- Spall, Michael A. (2004). "Boundary Currents and Watermass Transformation in Marginal Seas". J. Phys. Oceanogr. 34 (5): 1197–1213. Bibcode:2004JPO....34.1197S. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(2004)034<1197:BCAWTI>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 128436726.

- Grønlands forhistorie, ed. Hans Christian Gulløv, Gyldendal 2005, ISBN 87-02-01724-5

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- "Ice-sheet sourced juxtaposed turbidite systems in Labrador Sea". Geoscience Canada. 24 (1): 3.

- Reinhard Hesse And Allan Rakofsky (1992). "Deep-Sea Channel/Submarine-Yazoo System of the Labrador Sea: A New Deep-Water Facies Model (1)". AAPG Bulletin. 76. doi:10.1306/BDFF88A8-1718-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- Hesse, R., Klauck, I., Khodabakhsh, S. & Ryan, W. B. F. (1997). Thomas A. Davies (ed.). Glaciated continental margins: an atlas of acoustic images. Glacimarine drainage systems in the deep-sea: the NAMOC system of the Labrador Sea and its sibling. Springer. p. 286. ISBN 0-412-79340-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Einsele, Gerhard (2000). Sedimentary basins: evolution, facies, and sediment budget. Springer. p. 234. ISBN 3-540-66193-X.

- Kenneth F. Drinkwater, R. Allyn Clarke. "Labrador Sea". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- Petrie, B.; A. Isenor (1985). "The near-surface circulation and exchange in the Newfoundland Grand Banks region" (PDF). Atmosphere-Ocean. 23 (3): 209–227. doi:10.1080/07055900.1985.9649225. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 21, 2010.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Baffin Current". Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Labrador Current". Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- Wallace Gary Ernst (2000). Earth systems: processes and issues. Cambridge University Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-521-47895-2.

- Talley, L.D.; McCartney, M.S. (1982). "Distribution and Circulation of Labrador Sea Water" (PDF). Journal of Physical Oceanography. 12 (11): 1189. Bibcode:1982JPO....12.1189T. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1982)012<1189:DACOLS>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0485.

- National Research Council (U.S.) (1981). Maritime services to support polar resource development. pp. 6–7.

- COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Beluga Whale. Dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca (2012-07-31). Retrieved on 2013-03-20.

- Anthony Bertram Dickinson; Chesley W. Sanger (2005). Twentieth-century shore-station whaling in Newfoundland and Labrador. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-7735-2881-4.

- Ducher, William (1894). "The Labrador Duck – another specimen, with additional data respecting extant specimens" (PDF). Auk. 11 (1): 4–12. doi:10.2307/4067622. JSTOR 4067622.

- E. A. Goldman (1937). "The Wolves of North America". Journal of Mammalogy. 18 (1): 37–45. doi:10.2307/1374306. JSTOR 1374306.

- G.R. Parker; S. Luttich (1986). "Characteristics of the Wolf (Canis lupus lubrudorius Goldman) in Northern Quebec and Labrador" (PDF). Arctic. 39 (2): 145–149. doi:10.14430/arctic2062.

- Anonymous (2006). The Moravians in Labrador. pp. 9–11. ISBN 1-4068-0512-2.

- "Eastern Canadian Shield taiga". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Ledum groenlandicum Oeder – Labrador Tea. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2013-03-20.