Beothuk

The Beothuk (/biːˈɒtək/ or /ˈbeɪ.əθʊk/; also spelled Beothuck)[1][2] were a group of indigenous people who lived on the island of Newfoundland.[3]

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

.JPG.webp) |

|

Beginning around AD 1500, the Beothuk culture formed. This appeared to be the most recent cultural manifestation of peoples who first migrated from Labrador to present-day Newfoundland around AD 1. The ancestors of this group had three earlier cultural phases, each lasting approximately 500 years.[4]

Description

The Beothuk lived throughout the island of Newfoundland, particularly in the Notre Dame and Bonavista Bay areas. Estimates vary as to the number of Beothuk at the time of contact with Europeans. Beothuk researcher Ingeborg Marshall has argued that a valid understanding of Beothuk history and culture is directly impacted by how and by whom historical records were created, pointing to the ethnocentric nature of European accounts which positioned native populations as inherently inferior.[5] Scholars of the 19th and early 20th century estimated about 2,000 individuals at the time of European contact in the 15th century. There is purportedly good evidence that there may have been no more than 500 to 700 people.[6] They lived in independent, self-sufficient, extended family groups of 30 to 55 people.[7]

Like many other hunter-gathering peoples, they appear to have had band leaders but probably not more formal "chiefs". They lived in conical dwellings known as mamateeks, which were fortified for the winter season. These were constructed by arranging poles in a circle, tying them at the top, and covering them with birch bark. The floors were dug with hollows used for sleeping. A fireplace was made at the center.

During spring, the Beothuk used red ochre to paint not only their bodies but also their houses, canoes, weapons, household appliances, and musical instruments. This practice led Europeans to refer to them as "Red Indians". The use of ochre had great cultural significance. The decorating was done during an annual multi-day spring celebration. It designated tribal identity; for example, decorating newborn children was a way to welcome them into the tribe. Forbidding a person to wear ochre was a form of punishment.

Their main sources of food were caribou, salmon, and seals, augmented by harvesting other animal and plant species. The Beothuk followed the seasonal migratory habits of their principal quarry. In the fall, they set up deer fences, sometimes 30–40 miles (48–64 km) long, used to drive migrating caribou toward waiting hunters armed with bows and arrows.[8]

The Beothuk are also known to have made a pudding out of tree sap and the dried yolk of the eggs of the great auk.[9] They preserved surplus food for use during winter, trapped various fur-bearing animals, and worked their skins for warm clothing. The fur side was worn next to the skin, to trap air against a person's body.

Beothuk canoes were made of caribou or seal skin, and the bow of the canoe was stiffened with spruce bark. Canoes resembled kayaks and were said to be fifteen feet (4.57 m) in length and two and a half feet (0.76 m) in width with enough room to carry children, dogs and property.[10]

The Beothuk followed elaborate burial practices. After wrapping the bodies in birch bark, they buried the dead in isolated locations. In one form, a shallow grave was covered with a rock pile. At other times they laid the body on a scaffold, or placed it in a burial box, with the knees folded. The survivors placed offerings at burial sites to accompany the dead, such as figurines, pendants, and replicas of tools.[8]

European exploration

About 1000 AD, Norse explorers encountered natives in northern Newfoundland, who may have been ancestors of the later Beothuk, or Dorset inhabitants of Labrador and Newfoundland. The Norse called them skrælingjar ("skraelings" or barbarians).[11] Beginning in 1497, with the arrival of the Italian John Cabot, sailing under the auspices of the English crown, waves of European explorers and settlers had more contacts.

Unlike some other native groups, the Beothuk tried to avoid contact with Europeans; they moved inland as European settlements grew. The Beothuk visited their former camps only to pick up metal objects. They would also collect any tools, shelters, and building materials left by the European fishermen who had dried and cured their catch before taking it to Europe at the end of the season. Contact between Europeans and the Beothuk was usually negative for one side, with a few exceptions like John Guy's party in 1612. Settlers and the Beothuk competed for natural resources such as salmon, seals, and birds. In the interior, fur trappers established traplines, disrupted the caribou hunts, and pillaged Beothuk stores, camps and supplies. The Beothuk would steal traps to reuse the metals, and steal from the homes and shelters of Europeans and sometimes ambush them.[12] These encounters led to enmity and mutual violence. With superior arms technology, the settlers generally had the upper hand in hunting and warfare. (Unlike other indigenous peoples, the Beothuk appeared to have had no interest in adopting firearms.)[13]

Intermittently, Europeans attempted to improve relations with the Beothuk. Examples included expeditions by naval lieutenants George Cartwright in 1768 and David Buchan in 1811. Cartwright's expedition was commissioned by Governor Hugh Palliser; he found no Beothuk, but brought back important cultural information.

Governor John Duckworth commissioned Buchan's expedition. Although undertaken for information gathering, this expedition ended in violence. Buchan's party encountered several Beothuk near Red Indian Lake. After an initially friendly reception, Buchan left two of his men behind with the Beothuk. The next day, he found them murdered and mutilated. According to the Beothuk Shanawdithit's later account, the marines were killed when one refused to give up his jacket and both ran away.[12]

In 2010, a team of European researchers announced the discovery of a previously unknown mitochondrial DNA sequence in Iceland, which they further suggest may have New World origins. If the latter is true, one possible explanation for its appearance in modern Iceland would be intermarriage with a North American indigenous woman, possibly a Beothuk.[14]

Causes of starvation

The Beothuks avoided Europeans in Newfoundland by moving inland from their traditional settlements. First, they emigrated to different coastal areas of Newfoundland, places the Europeans did not have fish-camps, but they were over-run. Then, they emigrated to inland Newfoundland.[15] The Beothuks' main food sources were caribou, fish, and seals; their emigration deprived them of two of these. This led to the over-hunting of caribou, leading to a decrease in the caribou population in Newfoundland. The Beothuks emigrated from their traditional land and lifestyle into ecosystems unable to support them, causing under-nourishment and, eventually, starvation.[16]

Extinction

._Daughter_of_Beothuk_woman_called_'Elizabeth'_%2526_husband_Samuel_Anstey_(1832-1923)._Twillingate.jpg.webp)

_1858-1895._Granddaughter_of_Beothuk_woman_known_as_'Elizabeth'._Twillingate.jpg.webp)

Population estimates of Beothuks remaining at the end of the first decade of the 19th century vary widely, from about 150 up to 3,000.[17] Information about the Beothuk was based on accounts by the woman Shanawdithit, who told about the people who "wintered on the Exploits River or at Red Indian Lake and resorted to the coast in Notre Dame Bay". References in records also noted some survivors on the Northern Peninsula in the early 19th century.[18]

During the colonial period, the Beothuk people also endured territorial pressure from Native groups: Mi'kmaq migrants from Cape Breton Island,[19] and Inuit from Labrador. "The Beothuk were unable to procure sufficient subsistence within the areas left to them."[20] They entered into a cycle of violence with some of the newcomers. Beothuk numbers dwindled rapidly due to a combination of factors, including:

- loss of access to important food sources, from the competition with Inuit and Mi'kmaq as well as European settlers;

- infectious diseases to which they had no immunity, such as smallpox, introduced by European contact;

- endemic tuberculosis (TB), which weakened tribal members; and

- violent encounters with trappers, settlers, and other natives.

By 1829, with the death of Shanawdithit, the people were declared extinct.[8]

Oral histories suggest a few Beothuk survived around the region of the Exploits River, Twillingate, Newfoundland; and Labrador; and formed unions with European colonists, Inuit and Mi'kmaq.[21] Some families from Twillingate claim descent from the Beothuk people of the early 19th century.

1910, a 75-year-old Native woman named Santu Toney, claiming she was the daughter of a Mi'kmaq mother and a Beothuk father, recorded a song in the Beothuk language for the American anthropologist Frank Speck. He was doing field studies in the area. She said her father taught her the song.[22]

Since Santu Toney was born about 1835, this may be evidence some Beothuk people survived beyond the death of Shanawdithit in 1829. Contemporary researchers tried to transcribe the song, as well as improve the recording by current methods. Native groups learned the song to use in celebrations of tradition.[23]

Genocide

Historians sometimes disagree over what constitutes genocide, and their disagreements may be based on political agendas.[24]

If a campaign of genocide occurred, it was explicitly without official sanction no later than 1759, any such action thereafter being in violation of Governor John Byron's proclamation criminalizing violence against the Beothuk,[19] as well as the subsequent Proclamation issued by Governor John Holloway on July 30, 1807, which prohibited mistreatment of the Beothuk and offered a reward for any information on such mistreatment.[25]

Notable Beothuk captives

Several Beothuk persons captured by the English were well documented.

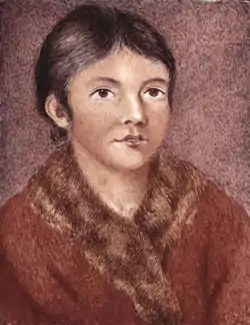

Demasduit

Demasduit was a Beothuk woman about 23-years old at the time she was captured by the British near Red Indian Lake in March 1819.

The governor of Newfoundland was seeking to encourage trade and end hostilities between the Beothuk and the British. He approved an expedition, to be led by Captain David Buchan, to recover a boat and other fishing gear foraged by the Beothuk. John Peyton Jr. led one of the groups. His father was John Peyton Sr., a salmon fisherman known for his hostility toward the small tribe. On a raid, Peyton's group killed Demasduit's husband Nonosbawsut, then ran her down in the snow. She pleaded for her life, baring her breasts to show she was a nursing mother. They took Demasduit to Twillingate, so Peyton Jr. could collect his bounty on her. Her baby died. Peyton Jr. was later appointed Justice of the Peace at Twillingate, Newfoundland.

The British called Demasduit Mary March after the month she was taken. The government agents took her to St. John's, Newfoundland. The colonial government hoped to make Demasduit comfortable while she was with the British so she might be a bridge between them and the Beothuk. Demasduit learned some English, and taught the settlers about 200 words of the Beothuk language. In January 1820, Demasduit was released to rejoin her kin, but she died of tuberculosis on the voyage to Notre Dame Bay.

Shanawdithit

Shanawdithit was Demasduit's niece and the last known full-blooded Beothuk. April 1823, she was in her early twenties. She, her mother, and sister sought food and help from a British trapper. They were starving. The three were taken to St. John's, but her mother and sister died of tuberculosis, an epidemic among the First Nations. Called Nancy April by the British, Shanawdithit lived for several years in the home of John Peyton, Jr. as a servant.

The explorer William Cormack founded the Beothuk Institute in 1827 to foster friendly dealings with the Beothuk and support their culture. His expeditions found Beothuk artifacts but he also learned the society was dying out. Learning of Shanawdithit, in the winter 1828–1829, Cormack brought her to his center so he could learn from her.[26] He drew funds from his institute to pay for her support.

Shanawdithit made ten drawings for Cormack, some of which showed parts of the island, and others illustrated Beothuk implements and dwellings, along with tribal notions and myths.[26] As she explained her drawings, she taught Cormack Beothuk vocabulary. She told him there were far fewer Beothuk than twenty years previously. To her knowledge, at the time she was taken, only a dozen Beothuk survived.[26] Despite medical care from the doctor William Carson, Shanawdithit died of tuberculosis in St. John's on 6 June 1829. At the time, there was no European cure for the disease.

Archaeology

The area around eastern Notre Dame Bay, on the northeast coast of Newfoundland, contains numerous archeological sites containing material from indigenous cultures. One of them is the Boyd's Cove site. At the foot of a bay, it is protected by a maze of islands sheltering it from waves and winds. The site was found in 1981 during an archeological survey to locate Beothuk sites to study their artifacts for insight into Beothuk culture.

Records were too limited to answer questions about the people. Few record-keeping Europeans contacted the Beothuk, and information about them is limited. By contrast, peoples such as the Huron or the Mi'kmaq inter-acted with the French missionaries, who studied and taught them and had extensive trade with French, Dutch, and English, all of whom made records of their encounters.

References document a Beothuk presence in the region of Notre Dame Bay in the last half of the 18th and early part of the 19th century. Previous archaeological surveys and amateur finds indicate it was likely the Beothuk lived in the area prior to European encounter. Eastern Notre Dame Bay is rich in animal and fish life: seals, fish, and seabirds, and its hinterland supported large caribou herds.

Archaeologists found sixteen Aboriginal sites, ranging in age from the Maritime Archaic Indian era (7000 BC – modern) through the Palaeo-Eskimo period, down to the Recent Indian (including the Beothuk) occupation. Two of the sites are associated with the historical Beothuk. Boyd's Cove, the larger of the two, is 3000 sq. m. and is on top of a 6-m glacial moraine. The coarse sand, gravel, and boulders were left behind by glaciers.

The artifacts provide answers to an economic question: why did/do the Beothuk avoid Europeans? The interiors of four houses and their environs produced some 1,157 nails, the majority of which were forged by the Beothuk. The site's occupants manufactured some sixty-seven projectile points (most made from nails and bones). They modified nails to use as what are believed to be scrapers to remove fat from animal hides, they straightened fish hooks and adapted them as awls, they fashioned lead into ornaments, and so on. In summary, the Boyd's Cove Beothuk took debris from an early modern European fishery and fashioned materials.

Genetics

2007, DNA testing was conducted on material from the teeth of Demasduit and her husband Nonosabasut, two Beothuk individuals buried in the 1820s. The results assigned them to Haplogroup X (mtDNA) and Haplogroup C (mtDNA), respectively, which are also found in current Mi'kmaq populations in Newfoundland. DNA research indicates they were solely of First Nation indigenous maternal ancestry, unlike some earlier studies suggesting an indigenous/European hybrid.[20] However, a 2011 analysis showed although the two Beothuk and living Mi'kmaq occur in the same haplogroups, SNP differences between Beothuk and Mi'kmaq individuals indicate they were dis-similar within those groups, and a 'close-relationship' theory was not supported.[27]

Footnotes

- "Dictionary of Newfoundland English (also known by the Mikmaq as the Pi'tawkewaq = up river people, from the mikmaq word pi'tawasi = going up river)". Heritage.nf.ca. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- Mithun, Marianne (2001). The Languages of Native North America (First paperback ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 368. ISBN 0-521-23228-7.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford University Press. pp. 155, 290. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Marshall, 1996, p. 7–10.

- Marshall, 1996, p. 7.

- Distribution and Size of the Beothuk Population, Leadership, and Communal Activities - A History and Ethnography of the Beothuk

- Marshall, 1996, p. 12.

- Anonymous (James McGregor) (1836). "Shaa-naan-dithit, or The Last of The Boëothics". Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. XIII (LXXV): 316–323. (Reprint, Toronto: Canadiana House, 1969)

- Cokinos, Christopher (2009). Hope Is the Thing with Feathers: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds. Penguin Group USA. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-58542-722-2.

- John Hewson (2007). "Santu's Song". Memorial University. 22 (1).

- Fagan, Brian M. (2005). Ancient North America: the archaeology of a continent. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28532-2.

- Upton LFS (1991). "The Extermination of the Beothucks of Newfoundland". In Miller J (ed.). Sweet promises: a reader on Indian-white relations in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 68–89. ISBN 0-8020-6818-9.

- Marshall, 1996, p. 33.

- Ebenesersdóttir; et al. (January 2011). "A new subclade of mtDNA haplogroup C1 found in icelanders: Evidence of pre-columbian contact?". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 144 (1): 92–99. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21419. PMID 21069749. Lay summary – Vancouver Sun (November 19, 2010).

- {Margaret Conrad, History of the Canadian Peoples fifth edition pg 256-257}

- "Disappearance of the Beothuk". Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- Marshall, 1996, p. 147.

- Marshall, 1996, p. 208.

- "The Beothuk of Newfoundland". visitnewfoundland.ca. January 5, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- Kuch, M; et al. (2007). "A preliminary analysis of the DNA and diet of the extinct Beothuk: A systematic approach to ancient human DNA" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 594–604. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20536. PMID 17205549. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2015.

- Marshall, 1996, p. 224-6.

- Hewson, John; Diamond, Beverley (January 2007). "Santu's Song". Newfoundland and Labrador Studies. Memorial University's Faculty of Arts. 22 (1): 227–257. ISSN 1715-1430. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- Perry, SJ (September 10, 2008). "Santu's Song: Memorable day for Beothuk Interpretation Centre". Porte Pilot. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- Rubinstein, WD (2004). "Genocide and Historical Debate: William D. Rubinstein Ascribes the Bitterness of Historians' Arguments to the Lack of an Agreed Definition and to Political Agendas". History Today. 54.

- "Holloway, John (1744-1826)". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Website. Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Website. August 2000. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- James P. Howley, F.G.S., "Drawings by Shanawdithit", The Beothucks or Red Indians: The Aboriginal Inhabitants of Newfoundland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915, Memorial University of Newfoundland & Labrador Website

- Pope, A (2011). "Mitogenomic and microsatellite variation in descendants of the founder population of Newfoundland: high genetic diversity in an historically isolated population" (PDF). Genome. 54 (2): 110–119. doi:10.1139/g10-102. PMID 21326367.

References

- Brown, Robert Craig, Reminiscences of James P. Howley: Selected Years. Toronto: Champlain Society Publications, 1997.

- Hewson, John. "Beothuk and Algonkian: Evidence Old and New", International Journal of American Linguistics, Vol. 34, No. 2 (April 1968), pp. 85–93.

- Holly, Donald H. Jr. "A Historiography of an Ahistoricity: On the Beothuk Indians", History and Anthropology, 2003, Vol. 14(2), pp. 127–140.

- Holly, Donald H. Jr. "The Beothuk on the eve of their extinction", Arctic Anthropology, 2000, Vol. 37(1), pp. 79–95.

- Howley, James P., The Beothucks or Red Indians, Cambridge University Press, 1918. Reprint: Prospero Books, Toronto. (2000). ISBN 1-55267-139-9.

- Marshall, I (1996). A History and Ethnography of the Beothuk. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-1390-6.

- Marshall, I (2001–2009). The Beothuk. Breakwater Books. ISBN 1-55081-258-0.

- Pastore, Ralph T., Shanawdithit's People: The Archaeology of the Beothuks. Breakwater Books, St. John's, Newfoundland, 1992. ISBN 0-929048-02-4.

- Renouf, M. A. P. "Prehistory of Newfoundland hunter-gatherers: extinctions or adaptations?" World Archaeology, Vol. 30(3): pp. 403–420 Arctic Archaeology 1999.

- Such, Peter, Vanished Peoples: The Archaic Dorset & Beothuk People of Newfoundland. NC Press, Toronto, 1978.

- Tuck, James A., Ancient People of Port au Choix: The Excavation of an Archaic Indian Cemetery in Newfoundland. Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1994.

- Winter, Keith John, Shananditti: The Last of the Beothuks. J.J. Douglas Ltd., North Vancouver, B.C., 1975. ISBN 0-88894-086-6.

- Assiniwi, Bernard, "La saga des Béothuks". Babel, LEMÉAC, 1996. ISBN 2-7609-2018-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beothuk. |

- The Beothuks, Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage.

- Beothuk, Native Languages.

- Ideas on CBC program about Demasduwit

.svg.png.webp)