Laghman Province

Laghman (Pashto/Persian: لغمان) is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, located in the eastern part of the country. It has a population of about 493,500,[1] which is multi-ethnic and mostly a rural society. The city of Mihtarlam serves as the capital of the province. In some historical texts the name is written as "Lamghan" or as "Lamghanat".

Laghman

لغمان | |

|---|---|

Lush greenery stands in stark contrast to the surrounding desert in Laghman Province | |

Map of Afghanistan with Laghman highlighted | |

| Coordinates (Capital): 34.66°N 70.20°E | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Mihtarlam |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Rahmatullah Yarmal |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,842.6 km2 (1,483.6 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 493,488 |

| • Density | 130/km2 (330/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+4:30 (Afghanistan Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | AF-LAG |

| Main languages | Pashto Pashayi |

Etymology

Laghman or Lamghan is originally named after Lamech (Mether Lam Baba), the father of Noah.[2]

History

Located currently at the Kabul Museum are Aramaic inscriptions that were found in Laghman which indicated an ancient trade route from India to Palmyra.[3] Aramaic was the bureaucratic script language of the Achaemenids whose influence had extended toward Laghman.[4] During the invasions of Alexander the Great, the area was known as Lampaka.[5]

Inscriptions in Aramaic dating from the Mauryan Dynasty were found in Laghman which discussed the conversion of Ashoka to Buddhism.[6] The inscription mentions that the distance to Palmyra is 300 dhanusha or yojana.

The Mahamayuri Tantra dated to between 1-3rd century mentions a number of popular Yaksha shrines. It mentions Yaksh Kalahapriya being worshipped in Lampaka.[7]

In the seventh century, the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang visited Laghman, which he called "Lan-p'o" and considered part of India. He indicated the presence of Mahayana Buddhists and numerous Hindus:

"For several centuries the native dynasty had ceased to exist, great families fought for preeminence, and the state had recently become a dependency of Kapis. The country produced upland rice and sugar-cane, and it had much wood but little fruit; the climate was mild with little frost and no snow. [...] There were above ten Buddhist monasteries and a few Brethren the most of whom were Mahayanists. The non-Buddhists had a score or two of temples and they were very numerous."[8]

The Hudud al-'alam which was finished in 982 AD mentioned the presence of some idol worshipping temples in the area.[9]

The Kabul Shahis only retained Lamghan in the Kabul-Gandhara area by the time of Alp-tegin. According to Firishta, Sabuktigin had already begun raiding Lamghan under Alp-tegin.[10] He crossed the Khyber Pass many times and raided the territory of Jayapala.[11] He plundered the forts in the outlying provinces of the Kabul Shahi and captured many cities, acquiring huge booty.[12] He also established Islam at many places. Jaipal in retaliation marched with a large force into the valley of Lamghan (Jalalabad) where he clashed with Sabuktigin and his son. The battle stretched on several days until a snow storm affected Jaipala's strategies, forcing him to sue for peace.[11]

Jayapala then returned to Waihind but broke the treaty and mistreated the amirs sent to collect the tribute. Sabuktigin launched another invasion in retaliation.[13] According to al-Utbi, Sabuktigin attacked Lamghan, conquering it and burning the residences of the "infidels" while also demolishing its idol-temples and establishing Islam.[14] He advanced and butchered the idolaters, destroying the temples and plundering their shrines, even risking frostbite on their hands counting the large booty.[15]

To avenge the savage attack of Sabuktigin, Jayapala, who has earlier taken his envoys as hostage, decided to go to war again in revenge. The forces of Kabul Shahi were however routed and those still alive were killed in the forest or drowned in the river.[16] Thks second battle that took place between Sabuktigin and Jayapala in 988 A.D., resulted in the former capturing territory between Lamghan and Peshawar. Al-Ubti also states that the Afghans and Khaljis, living there as nomads, took the oath of allegiance to him and were recruited into his army.[17] Sabuktigin won one of his greatest battles in Laghman against Jayapala and his army numbering 100,000.[18]

Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni built the Tomb of Lamech, amid gardens, over the site of his presumed grave, 50 kilometres from Mihtarlam.[19]

The area later fell to the Ghurids followed by the Khilis and Timurids.

During the early years of the 16th century, the Mughal ruler Babur spent much time in Laghman, and in Baburnama (memoirs of Babur) he expatiated on the beauty of forested hillsides and the fertility of the valley bottoms of the region.[9] Laghman was recognized as a dependent district of Kabulistan in the Mughal era,[20] and according to Baburnama, "Greater Lamghanat" included the Muslim-settled part of the Kafiristan, including the easterly one of Kunar River. Laghman was the base for expeditions against the non-believers and was frequently mentioned in accounts of jihads led by Mughal emperor Akbar's younger brother, Mohammad Hakim, who was the governor of Kabul.[9] In 1747, Ahmad Shah Durrani defeated the Mughals and made the territory part of the Durrani Empire. In the late nineteenth century, Amir Abdur Rahman Khan forced the remaining kafirs (Nuristani people) to accept Islam.

Recent history

During the Soviet-Afghan war and the battles that followed between the rivaling warlords, many homes and business establishments in the province were destroyed. In addition, the Soviets are said to have employed a strategy that targeted and destroyed the agricultural infrastructure of Laghman.[21]

As of 2007, an International Security Assistance Force Provincial Reconstruction Team led by the United States is based at Mihtarlam.

Politics and governance

The current governor of the province is Rahmatullah Yarmal.[22] The city of Mihtarlam is the capital of the province. All law enforcement activities throughout the province are controlled by the Afghan National Police (ANP). The provincial police chief represents the Ministry of the Interior in Kabul. The ANP is backed by other Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), including the National Directorate of Security (NDS) and NATO-led forces.

Healthcare

The percentage of households with clean drinking water fell from 39% in 2005 to 34% in 2011.[23] The percentage of births attended to by a skilled birth attendant increased from 3% in 2005 to 36% in 2011.[23]

Education

The overall literacy rate (6+ years of age) increased from 14% in 2005 to 26% in 2011.[23] The overall net enrolment rate (6–13 years of age) increased from 48% in 2005 to 52% in 2011.[23]

Infrastructure and economy

The Alingar and Alishing rivers pass through Laghman, as the province is known for its lushness. Laghman has sizable amounts of irrigated land as one can find scores of fruits and vegetables from Laghman in Kabul. Other main crops in Laghman include rice, wheat and cotton as many people living in the area are involved in agricultural trade and business.

Laghman also has an array of precious stones and minerals,[24] as it is well known for being a relatively untapped source of the Tourmaline and Spodumene gemstones which are reported to be in abundance at the northern portions of the province.[25]

Demography

The total population of the province is about 493,500, which is multi-ethnic and mostly a rural society.[1][26] According to the Naval Postgraduate School, as of 2010 the ethnic groups of the province are as follows: 80% Pashtun, 5% Tajik, 15% Pashai and Nuristani (Kata).[27][28] The people of Laghman are overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim.

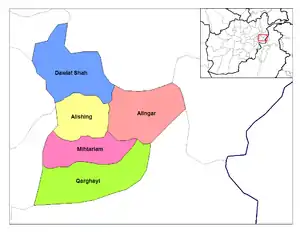

Districts

| District | Capital | Population (2020)[1] | Area[29] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alingar | 109,343 | 95% Pashtun, 5% Pashayi,[30] | ||

| Alishing | 80,645 | 60% Pashayi, 20% Pashtun, 20% Tajik[31] | ||

| Dawlat Shah | 37,599 | 70% Pashayi, 25% Pashtun 5% Tajiks[32] | ||

| Mihtarlam | Mihtarlam | 146,727 | 90% Pashtun, 5% Tajik, 5% Pashayi[33] | |

| Qarghayi | 110,804 | 80% Pashtun, 5% Tajik, 15% Pashai[34] | ||

| Badpash | 8,370 | 100% pashtuns |

Notable people from this province

- Mohammad Hanif Atmar - national security advisor, former Education and Interior Minister

- Mirwais Azizi - founder and owner of Azizi Bank

- Mohammad Shafiq Hamdam - writer and political activist

- Abdul Khaliq Hussaini - Former Senator, political activist

- Hafizullah Khaled - humanitarian, peace activist and writer

- Zalmay Khalilzad - statesman, diplomat and businessman

- Abdullah Laghmani - former Deputy Intelligence Officer of Afghanistan

- Wafadar Momand - cricketer

- Gul Pacha Ulfat - poet and writer

- Ahmad Zahir - singer and songwriter

- Samiuddin Zhouand - former President of the Court of Appeal, former acting minister for justice and deputy attorney-general, jurist and academic

References

- "Estimated Population of Afghanistan 2020-21" (PDF). nsia.gov.af. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- "Afghanistan: Metar Lamech Shrine". www.culturalprofiles.org.uk. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- Cultural policy in Afghanistan; Studies and documents on cultural policies; 1975

- "AŚOKA". iranicaonline.org.

- Henning, W. B. (2 April 2018). "The Aramaic Inscription of Asoka Found in Lampāka". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 13 (1): 80–88. JSTOR 609063.

- Kurt A. Behrend (2004). Handbuch Der Orientalistik: India. The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara, Part 2, Volume 1. p. 39. ISBN 9004135952.

- THE MAHAMAYURI VIDYARAJNI SUTRA 佛母大孔雀明王經, Translated into English by Cheng Yew Chung based on Amoghavajra’s Chinese Translation (Taisho Volume 19, Number 982)

- Watters, Thomas (1904). On Yuan Chwang's travels in India, 629-645 A.D. Royal Asiatic Society.

- Schimmel, Annemarie. "Islam in India and Pakistan". In Bosworth, CE; van Donzel, E; Lewis, B; Pellet, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume V. p. 649. ISBN 90-04-07819-3.

- Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th-11th Centuries. Brill. 2002. p. 126. ISBN 0391041738.

- K. A. Nilakanta Sastri. History of India, Volume 2. Viswanathan. p. 10.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1966). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The struggle for empire. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 3.

- Roy, Kaushik (3 June 2015). Warfare in Pre-British India – 1500BCE to 1740CE. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 9781317586920.

- Richard Maxwell Eaton. Essays on Islam and Indian History. Oxford University Press. p. 98.

- Keay, John (12 April 2011). India: A History. Revised and Updated. Grove/Atlantic Inc. p. 212. ISBN 9780802195500.

- Keay, John (12 April 2011). India: A History. Revised and Updated. Grove/Atlantic Inc. pp. 212–213. ISBN 9780802195500.

- Syed Jabir Raza. "The Afghans and their relations with the Ghaznavids and the Ghurids". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress: 786.

- The History of India: The Hindu and Mahometan Periods, Mountstuart Elphinstone, p. 321.

- Elphinstone, Mountstuart, "SULTÁN MAHMÚD. (997–1030.)", The History of India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 532–579, ISBN 978-1-139-50762-2, retrieved 2020-12-15

- The Garden of Eight Paradises: Babur and the Culture of Central Asia, Afghanistan

- How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict, Arreguin-Toft, pg. 186

- "Ghani appoints new governors for five provinces of Afghanistan". The Khaama Press News Agency. 2020-07-07. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- Archive, Civil Military Fusion Centre Archived 2014-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pegmatites of Laghman, Nuristan, Afghanistan". palagems.com.

- Gemstones of Afghanistan, Chamberline, pg. 146

- "Settled Population of Laghman province by Civil Division, Urban, Rural and Sex-2012-13" (PDF). Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Central Statistics Organization. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- "Welcome - Naval Postgraduate School" (PDF). www.nps.edu. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Laghman Province". Program for Culture & Conflict Studies. Naval Postgraduate School. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- "FAO in Afghanistan - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- (PDF). 2005-10-27 https://web.archive.org/web/20051027181412/http://www.aims.org.af/afg/dist_profiles/unhcr_district_profiles/eastern/laghman/alishing.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-27. Retrieved 2020-10-09. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - (PDF). 2005-10-27 https://web.archive.org/web/20051027181412/http://www.aims.org.af/afg/dist_profiles/unhcr_district_profiles/eastern/laghman/alishing.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-27. Retrieved 2020-10-09. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - (PDF). 2005-10-27 https://web.archive.org/web/20051027185136/http://www.aims.org.af/afg/dist_profiles/unhcr_district_profiles/eastern/laghman/dawlat_shah.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-27. Retrieved 2020-10-09. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - (PDF). 2016-03-03 https://web.archive.org/web/20160303192917/http://www.aims.org.af/afg/dist_profiles/unhcr_district_profiles/eastern/laghman/mihtarlam.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2020-10-09. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - (PDF). 2005-10-27 https://web.archive.org/web/20051027181437/http://www.aims.org.af/afg/dist_profiles/unhcr_district_profiles/eastern/laghman/qarghayi.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-27. Retrieved 2020-10-09. Missing or empty

|title=(help)