Sand War

The Sand War or the Sands War (Arabic: حرب الرمال ḥarb ar-rimāl) was a border conflict between Algeria and Morocco in October 1963. It resulted largely from the Moroccan government's claim to portions of Algeria's Tindouf and Béchar provinces. The Sand War led to heightened tensions between the two countries for several decades. It was also notable for a short-lived Cuban and Egyptian military intervention on behalf of Algeria, and for ushering in the first multinational peacekeeping mission carried out by the Organisation of African Unity.

| Sand War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Cold War and the Cold War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Support: |

Support: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

39 killed 57 captured[7] or: 200 killed[8] |

60 killed 250 wounded[9] or: 300 killed[8] 379 captured[7] | ||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Morocco |

|

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Algeria |

|

Background

.jpg.webp)

Three factors contributed to the outbreak of this conflict: the absence of a precise delineation of the border between Algeria and Morocco, the discovery of important mineral resources in the disputed area, and the Moroccan irredentism fueled by the Greater Morocco[10] ideology of the Istiqlal Party and Allal al-Fassi.[11]

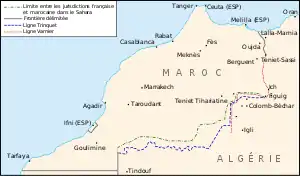

Before French colonization of the region in the nineteenth century, part of south and west Algeria were under Moroccan influence and no border was defined.[12] In the Treaty of Lalla Maghnia (March 18, 1845), which set the border between French Algeria and Morocco, it is stipulated that "a territory without water is uninhabitable and its boundaries are superfluous"[13] and the border is delineated over only 165 km.[14] Beyond that there is only one border area, without limit, punctuated by tribal territories attached to Morocco or Algeria.

In the 1890s, the French administration and military called for the annexation of the Touat, the Gourara and the Tidikelt,[15] a complex that had been part of the Moroccan Empire for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria.[16]

The French 19th Army Corps' Oran and Algiers divisions fought the Aït Khabbash, a fraction of the Aït Ounbgui khams of the Aït Atta confederation. The conflict ended with the annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt complex by France in 1901.[17]

After Morocco became a French protectorate in 1912, the French administration set borders between the two territories, but these tracks were often misidentified (Varnier line in 1912, Trinquet line in 1938), and varied from one map to another,[18] since for the French administration these were not international borders and the area was virtually uninhabited.[19] The discovery of large deposits of oil and minerals (iron, manganese) in the region led France to define more precisely the territories, and in 1952 the French decided to integrate Tindouf and Colomb-Bechar to the French departments of Algeria.[20]

In 1956 France relinquished its protectorate in Morocco, which immediately demanded the return of the disputed departments, especially Tindouf.[21] The French government refused.[22]

During the Algerian War, Morocco backed the National Liberation Front, Algeria's leading nationalist movement, in its guerrilla campaign against the French.[21] However, one of the FLN's primary objectives was to prevent France from splitting the strategic Sahara regions from a future Algerian state. It was therefore disinclined to support Morocco's historical claims to Tindouf and Bechar or the concept of a Greater Morocco.[10]

Upon Algerian independence, the FLN announced it would apply the principle of uti possidetis to pre-existing colonial borders. King Hassan II of Morocco visited Algiers in March 1963 to discuss the undefined borders, but Algeria's President Ahmed Ben Bella believed the matter should be resolved at a later date.[23] Ben Bella's fledgling administration was still attempting to rebuild the country after the enormous damage caused by the Algerian War, and was already preoccupied with a Berber rebellion under Hocine Aït Ahmed in the Kabyle mountains. Algerian authorities suspected that Morocco was inciting the revolt, while Hassan was anxious about his own opposition's reverence for Algeria, escalating tensions between the nations.[24] These factors prompted Hassan to begin moving troops towards Tindouf.[22]

War

Weeks of skirmishes along the border eventually escalated into a full-blown confrontation on September 25, 1963, with intense fighting around the oasis towns of Tindouf and Figuig.[1] The Royal Moroccan Army soon crossed into Algeria in force and succeeded in taking the two border posts of Hassi-Beida and Tindjoub.[25]

The Algerian military, recently formed from the guerrilla ranks of the FLN's Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) was still oriented towards asymmetric warfare, and had little heavy weapons.[26] Its logistics was also complicated by its vast array of largely obsolete weapons from a number of diverse sources, including France, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and the United States.[27] The Algerian army had ordered a large number of AMX-13 light tanks from France in 1962,[28] but at the time of the fighting only twelve were in service.[27] Ironically at least four AMX-13s had been also been donated by Morocco a year earlier.[28] The Soviet Union supplied Algeria with ten T-34 tanks, but these were equipped for clearing minefields and were delivered without turrets or armament.[28][27] The Algerian army also lacked trucks, aircraft, and jeeps.[29]

Morocco's armed forces were smaller, but comparatively well-equipped and frequently took advantage of their superior firepower on the battlefield.[12][30] They possessed forty T-54 main battle tanks that they had purchased from the Soviet Union, twelve SU-100 tank destroyers, seventeen AMX-13s, and a fleet of gun-armed Panhard EBR armored cars.[29] Morocco also possessed modern strike aircraft, while Algeria did not.[28]

Despite internal discontent with the Algerian government, most of the country supported the war effort, which Algerians generally perceived as an act of Moroccan aggression. Even in regions where Ben Bella's regime remained deeply unpopular, such as Kabylie, the population offered to take up arms against the Moroccan invaders.[2] Morocco's invasion proved to be a diplomatic blunder, as the other Arab and African states refused to recognize its border claims. Egypt even began sending troops and defense hardware in late October to bolster the Algerian military.[31] Morocco's Western allies, namely the United States, did not provide assistance, despite Morocco's formal requests to the Kennedy Administration for military aid.[31] The United States feared the escalation and internationalization of the war, particularly wanting to avoid Soviet intervention, and therefore advocated for the peaceful resolution of the conflict.[31]

On October 5, representatives from Morocco and Algeria convened at Oujda to negotiate, but they were unable to deliver a solution.[25] The Moroccans were determined to adjust the border, which the Algerians would not allow, resulting in an impasse.[25]

The Algerian forces began to retaliate against the Moroccan advances, taking back the ports of Hassi-Beida and Tindjoub on October 8.[32] This prompted further attempts at negotiations, but these proved ineffectual as well.[32] On October 13, 1963, Moroccan ground units launched a major offensive on Tindouf. It stalled due to unexpectedly stubborn resistance from the town's Algerian and Egyptian garrison.[33] The Algerians attacked the town of Ich on October 18, enlarging the war to the North.[34]

On October 22, hundreds of Cuban troops arrived at Oran.[35] The troops were sent at the request of Ben Bella, though he would later deny this in 1997.[36] Just years after the victory of their own revolution, many Cubans identified with the Algerians and were eager to support them.[29] They also suspected that Washington was hoping the war would precipitate Ben Bella's downfall, which Castro was determined to prevent.[29] For these reasons, the Cuban Government formed the Grupo Especial de Instrucción to be sent to Algeria.[37] Its forces included twenty-two T-34 tanks, eighteen 120-mm mortars, a battery of 57-mm recoilless rifles, anti-aircraft artillery with eighteen guns, and eighteen 122mm field guns with the crews to operate them.[38] The unit was made up of 686 men under the command of Efigenio Ameijeiras.[38] Although they were initially described as an advisory contingent to train the Algerian army, Fidel Castro also authorized their deployment in combat actions to safeguard Algeria's territorial integrity.[39] The Cubans offloaded their equipment and transported it to the southwestern front by rail. The troops provided training to the Algerians, and their medical team offered the population free healthcare.[40] While Castro had hoped to keep Cuba's intervention covert, and a number of the Cuban personnel wore Algerian uniforms, they were observed by French military and diplomatic staff in Oran and word of their presence soon leaked to the Western press.[39] Algeria and Cuba planned a major counteroffensive, Operation Dignidad, aimed at driving the Moroccan forces back across the border and capturing Berguent. However, Ben Bella suspended the attack in order to proceed with negotiations to end the war peacefully.[31]

Moroccan forces had planned a second offensive on Tindouf and occupied positions about four kilometres from the settlement.[22] However, Hassan was reluctant to authorise it, fearing that another battle would prompt further military intervention from Algeria's allies.[22]

Multiple actors, including the Arab League, Tunisia's Habib Bourguiba, Libya's King Idris, and Ethiopia's Emperor Haile Selassie, sought to moderate negotiations.[41] The United Nations received many pleas to issue a ceasefire appeal, but Secretary-General U Thant wanted to allow regional initiatives to pursue a solution.[41] On October 29, Hassan and Ben Bella met to negotiate in Bamako, Mali, joined by Emperor Selassie and Mali's President Modibo Keïta.[42] After the four leaders met alone on October 30, a truce was declared.[42] The accord mandated a ceasefire for November 2, and announced that a commission consisting of Moroccan, Algerian, Ethiopian, and Malian officers would decide the boundaries of a demilitarized zone.[42] It was also determined that an Ethiopian and Malian team would observe the neutrality of the demilitarized zone.[42] Finally, the accord suggested an immediate gathering of the Foreign Ministers of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU).[42] The meeting would be held to set up a commission to determine who was responsible for starting the war and to examine the frontier question and suggest methods for bringing about a lasting settlement of the conflict.[42]

The ceasefire was almost jeopardized on November 1, when Algerian troops assaulted a village near Figuig and positioned themselves against the town's airport.[43] The attack was denounced and dramatized by the Moroccan Government.[43] However, a Malian officer arrived on November 4 and enforced the Bamako Accord, ending the hostilities.[43]

The OAU mediated a formal peace treaty on February 20, 1964.[44] The treaty was signed in Mali following a number of preliminary discussions between Hassan and Ben Bella.[22] Terms of this agreement included a reaffirmation of the previously established borders in Algeria's favor and restoration of the status quo.[2] The demilitarized zone was maintained in the meantime, monitored by the OAU's first multinational peacekeeping force.[33]

Casualties

French sources reported Algerian casualties to be 60 dead and 250 wounded,[9] with later works giving a number of 300 Algerian dead.[8] Morocco officially reported to have suffered 39 dead.[7] Moroccan losses were probably lower than the Algerians' but are unconfirmed,[9] with later sources reporting 200 Moroccan dead.[8] About 57 Moroccans and 379 Algerians were taken prisoner.[7]

Aftermath

The Sand War laid the foundations for a lasting and often intensely hostile rivalry between Morocco and Algeria, exacerbated by the differences in political outlook between the conservative Moroccan monarchy and the revolutionary, Arab nationalist Algerian military government.[12][45] In January 1969, Algerian President Houari Boumediene made a state visit to Morocco and signed a treaty of friendship with Hassan's government at Ifrane.[22] The following year the two leaders set up a commission to demarcate the border and examine prospects for joint efforts to mine iron ore in the disputed region.[22] Morocco finally abandoned all claims to Algerian territory in 1972 with the Accord of Ifrane, though Morocco refused to ratify the agreement until 1989.[46]

The governments of both Morocco and Algeria used the war to describe opposition movements as unpatriotic. The Moroccan UNFP and the Algerian-Berber FFS of Aït Ahmed both suffered as a result of this. In the case of UNFP, its leader, Mehdi Ben Barka, sided with Algeria, and was sentenced to death in absentia as a result. In Algeria, the armed rebellion of the FFS in Kabylie fizzled out, as commanders defected to join the national forces against Morocco.

The rivalry between Morocco and Algeria exemplified in the Sand War also influenced Algeria's policy regarding the conflict in Western Sahara, with Algeria backing an independence-minded Sahrawi guerrilla organization, the Polisario Front, partly to curb Moroccan expansionism in the wake of the attempt to annex Tindouf.[47]

References

- Gleijeses 2002, p. 44.

- Gleijeses 2002, p. 47.

- "Within weeks the war ended in stalemate." Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1 edited by Alexander Mikaberidze Read here.

- Nicole Grimaud (1 January 1984). La politique extérieure de l'Algérie (1962-1978). KARTHALA Editions. p. 198. ISBN 978-2-86537-111-2.

L'armée française était en 1963 présente en Algérie et au Maroc. Le gouvernement français, officiellement neutre, comme le rappelle le Conseil des ministres du 25 octobre 1963, n'a pas pu empêcher que la coopération très étroite entre l'armée française et l'armée marocaine n'ait eu quelques répercussions sur le terrain. == The French Army was in 1963 present in Algeria and Morocco. The French government, officially neutral, as recalled by the Council of Ministers on October 25, 1963, could not prevent the very close cooperation between the French army and the Moroccan army from having some repercussions on the ground.

- Ottaway 1970, p. 166.

- Brian Latell (24 April 2012). Castro's Secrets: Cuban Intelligence, The CIA, and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy. St. Martin's Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-137-00001-9.

In this instance, unlike several others, the Cubans did no fighting; ; Algeria concluded an armistice with the Moroccan king.

- Hughes 2001, page 137

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2008). Warfare and Armed Conflicts (3rd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 9780786433193.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander, ed. (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. 1. ABC-Clio. ISBN 9781598843361.

- Touval 1967, p. 106.

- Biography of Allal al-Fassi

- Security Problems with Neighboring States – Countrystudies.us

- Article 6 du traité, cité par Zartman, page 163

- Reyner 1963, p. 316.

- Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Boundary in the Guir-Zousfana River Basin, in: African Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1970), pp. 37–56, Publ. Boston University African Studies Center: « The Algerian-Moroccan conflict can be said to have begun in 1890s when the administration and military in Algeria called for annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt, a sizable expanse of Saharan oases that was nominally a part of the Moroccan Empire (...) The Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt oases had been an appendage of the Moroccan Empire, jutting southeast for about 750 kilometers into the Saharan desert »

- Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Saharan Frontiers, Droz (1969), p.24 (ISBN 9782600044950) : « The Gourara-Touat-Tidikelt complex had been under Moroccan domination for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria »

- Claude Lefébure, Ayt Khebbach, impasse sud-est. L'involution d'une tribu marocaine exclue du Sahara, in: Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, N°41–42, 1986. Désert et montagne au Maghreb. pp. 136–157: « les Divisions d'Oran et d'Alger du 19e Corps d'armée n'ont pu conquérir le Touat et le Gourara qu'au prix de durs combats menés contre les semi-nomades d'obédience marocaine qui, depuis plus d'un siècle, imposaient leur protection aux oasiens »

- Reyner 1963, p. 317.

- Heggoy 1970.

- Farsoun & Paul 1976, p. 13.

- Bidwell 1998, p. 415.

- Bidwell 1998, p. 414.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013). "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)". The Journal of North African Studies. 18 (2): 327. doi:10.1080/13629387.2013.767041.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- How Cuba aided revolutionary Algeria in 1963 – themilitant.com

- Gleijeses 2002, p. 41.

- "Trade Registers". Armstrade.sipri.org. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Armed Conflict Events Data – Onwar.com

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013). "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)". The Journal of North African Studies. 18 (2): 328.

- Goldstein 1992, p. 174.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013). "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)". The Journal of North African Studies. 18 (2): 329.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 41; 46. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Gleijeses 2002, p. 45.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013). "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)". The Journal of North African Studies. 18 (2): 335.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013). "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)". The Journal of North African Studies. 18 (2): 339.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013). "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)". The Journal of North African Studies. 18 (2): 340.

- The 1963 border war and the 1972 treaty Archived 2006-09-27 at the Wayback Machine – Arabworld.nitle.org

- Algiers and Rabat, still miles apart – Le Monde Diplomatique

- Zunes, Stephen (Summer 1995). "Algeria, The Maghreb Union, & the Western Sahara Stalemate". Arab Studies Quarterly. 17 (3): 29. JSTOR 41858127.

- Mundy, Jacob; Zunes, Stephen (2014). "Western Sahara: Nonviolent resistance as a last resort". In Dudouet, Véronique (ed.). Civil Resistance and Conflict Transformation: Transitions from Armed to Nonviolent Struggle. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9781317697787.

Bibliography

- Bidwell, Robin (1998). Dictionary Of Modern Arab History. South Glamorgan: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-1138967670.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa, 1959–1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- Goldstein, Erik (1992). Wars and Peace Treaties: 1816 to 1991. Oxfordshire: Routledge Books. ISBN 978-0415078221.

- Farsoun, K.; Paul, J. (1976), "War in the Sahara: 1963", Middle East Research and Information Project (MERIP) Reports, 45 (45): 13–16, JSTOR 3011767. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Heggoy, A.A. (1970), "Colonial origins of the Algerian-Moroccan border conflict of October 1963", African Studies Review, 13 (1): 17–22, doi:10.2307/523680, JSTOR 523680. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Ottaway, David (1970), Algeria: The Politics of a Socialist Revolution, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520016552

- Reyner, A.S. (1963), "Morocco's international boundaries: a factual background", Journal of Modern African Studies, 1 (3): 313–326, doi:10.1017/s0022278x00001725, JSTOR 158912. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Torres-García, Ana (2013), "US diplomacy and the North African 'War of the Sands' (1963)", The Journal of North African Studies, 18 (2): 324–48, doi:10.1080/13629387.2013.767041

- Touval, S. (1967), "The Organization of African Unity and African borders", International Organization, 21 (1): 102–127, doi:10.1017/s0020818300013151, JSTOR 2705705. Link requires subscription to Jstor.

- Stephen O. Hughes, Morocco under King Hassan, Garnet & Ithaca Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8637-2285-7

- Zunes, Stephen (1995). "Algeria, The Maghreb Union, and the Western Sahara Stalemate." Arab Studies Quarterly, 17 (3): 23-36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41858127.

Further reading

- Pennell, C.R. (2000). Morocco Since 1830. A History. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6676-7.

- Stora, B. (2004). Algeria 1830–2000. A Short History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3715-1.