Arab Cold War

The Arab Cold War (Arabic: الحرب العربية الباردة al-Harb al-`Arabiyyah al-bāridah) was a period of political rivalry in the Arab world that occurred as part of the broader Cold War between, approximately, the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 that brought President Gamal Abdel Nasser to power in that country, and the 1979 Iranian Revolution which led Arab-Iranian tensions to eclipse intra-Arab strife. On one side were newly-established republics, led by Nasser's Egypt, and on the other side were traditionalist kingdoms led by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia.

| Arab Cold War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

Supported by:

|

Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Arab League |

|---|

|

Nasser espoused secular, pan-Arab nationalism and socialism as a response to the Islamism and rentierism of the kingdoms, as well as their perceived complicity in Western meddling in the region. He also saw himself as the foremost defender of Arab and Palestinian honor against the humiliation brought on by the independence of Israel and its victory in the 1948 war. Gradually, so-called Nasserism gained the support of other Arab presidents as they replaced monarchies in their countries, notably in Syria, Iraq, Libya, North Yemen, and Sudan. A number of attempts to unite these states in various configurations were made, but all ultimately failed.

In turn, the monarchies, namely Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Morocco, and the Gulf states, drew closer together as they sought to counter Nasser's influence through a variety of direct and indirect means.[1]

The expression "Arab Cold War" was coined by American political scientist and Middle East scholar Malcolm H. Kerr, in his 1965 book of that title, and subsequent editions.[2] Despite the moniker, though, the Arab Cold War was not per se a clash between capitalist and communist economic systems. What tied it into the wider conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union was that the U.S. backed the Saudi-led monarchies, while the Soviets supported the Nasserist republics, even though in theory almost all of the Arab states were part of the Non-Aligned Movement, and the nominally-socialist republics ruthlessly suppressed their own communist parties.

By the late 1970s, the Arab Cold War is considered to have ended due to a number of factors. The Soviet Union was unable to keep pace with the U.S. in supporting its Arab allies, the secular republics. These regimes became increasingly discredited among the public due to their stagnation, corruption, and continued failure to defeat Israel in the 1967 and 1973 wars. Nasser's successor Anwar Sadat made peace with Israel in 1978, and Islamism rose in popularity, culminating in the 1979 Iranian Revolution that established Iran as a regional power and made Egypt and Saudi Arabia allies in a new proxy conflict oriented around conflict between Shia and Sunni Muslim states.

Background

Over the period, the history of the Arab states varies widely. In 1956, the year of the Suez Crisis, only Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Tunisia, and Sudan, among the Arab states were republics; all, to some degree, subscribed to the Arab nationalist ideology, or at least paid lip-service to it. Jordan and Iraq were both Hashemite monarchies; Morocco, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and North Yemen all had independent dynasties; and Algeria, South Yemen, Oman, and the Trucial States remained under colonial rule. By 1960, Iraq, Tunisia, Algeria, and North Yemen had republican governments or Arab nationalist insurgencies while Lebanon had a near-civil war between US-aligned and Arab nationalist factions within the government.

Because conflicts in the period varied over time and with different locations and perspectives, it is dated differently, depending on sources. Jordanian sources, for example, date the commencement of the Arab Cold War to April 1957,[3] while Palestinian sources note the period of 1962 to 1967 as being most significant to them but within the larger Arab context.[4]

History

In 1952 King Farouk of Egypt was deposed by the Free Officers Movement under a program to dismantle feudalism and end British influence in Egypt. In 1953 the officers, led by Nasser, abolished the monarchy and declared Egypt a Republic.[5] On 26 July 1956, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, following the withdrawal of an offer by Britain and the United States to fund the building of the Aswan Dam, which was in response to Egypt's new ties with the Soviet Union. Britain, France, and Israel responded by occupying the Canal but were forced to back off in what is known as the Suez Crisis. Nasser "emerged" from the crisis with great prestige, as the "unchallenged leader of Arab nationalism".[6]

Nasser employed a number of political instruments in order to raise his profile across the Arab world – from radio programs such as the Voice of the Arabs to the organised dispatch of politically-active Egyptian professionals, usually teachers.

| 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 206 | 293 | 401 | 500 | 454 | 551 | 727 | 866 | 1027 |

| Jordan | - | 8 | 20 | 31 | 56 | - | - | - | - |

| Lebanon | 25 | 25 | 39 | 36 | 75 | 111 | 251 | 131 | 104 |

| Kuwait | 114 | 180 | 262 | 326 | 395 | 435 | 490 | 480 | 411 |

| Bahrain | 15 | 15 | 18 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 28 | 36 |

| Morocco | - | - | - | 20 | 75 | 81 | 175 | 210 | 334 |

| Sudan | - | - | - | - | 580 | 632 | 673 | 658 | 653 |

| Qatar | - | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 14 | 17 | 18 | 24 |

| Libya | 55 | 114 | 180 | 219 | 217 | 232 | 228 | 391 | 231 |

| Yemen | - | 12 | 11 | 8 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 0 |

| Iraq | 76 | 112 | 121 | 136 | 63 | 449 | - | - | - |

| Palestine | 13 | 32 | 34 | 37 | 46 | 120 | 166 | 175 | 165 |

| Somalia | - | - | 25 | 23 | 57 | 69 | 90 | 109 | 213 |

In July 1958, the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq was overthrown, with the king, crown prince and prime minister all killed by the nationalist revolutionaries. Iraq's monarchy was also replaced by a republic with an Arab nationalist orientation. Forces supporting Nasser and nationalism seemed ascendant, and older Arab monarchies seemed in peril.[6] In 1969, yet another Arab kingdom fell, when the Free Officers Movement of Libya, a group of rebel military officers led by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, overthrew the Kingdom of Libya led by King Idris.

In Saudi Arabia, Nasser's popularity was such that some Saudi princes (led by Prince Talal bin Abdul Aziz) rallied to his cause of Arab socialism.[6] In 1962, a Saudi Air Force pilot defected to Cairo.[6] There were signs of "unrest and subversion" in 1965 and 1966, "especially" in Saudi's oil-producing region.[6] In 1969, a Nasserist plot was uncovered by the Saudi government "involving 28 army officer, 34 air force officers, nine other military personnel, and 27 civilians."[8][6]

In the early 1960s, Nasser sent an expeditionary army to Yemen to support the anti-monarchist forces in the North Yemen Civil War. Yemen royalists were supported by Saudi Arabia and Jordan (both monarchies). Egyptian air power struck Saudi border towns like Najran in December 1962.[6]

By the late 1960s, Nasser's prestige was diminished by the political failure of the political union of Egypt and Syria, and the military failures in Yemen where the civil war stalemated despite his commitment of thousands of troops to overthrow the monarchists, and especially with Israel where Egypt lost the Sinai Peninsula and 10,000 to 15,000 troops killed during the Six-Day War. In late 1967, Nasser and Saudi foreign minister Prince Faisal signed a treaty under which Nasser would pull out his 20,000 troops from Yemen, Faisal would stop sending arms to Yemen royalists, and three neutral Arab states would send in observers.[9]

Islamic revival

Though far smaller in population than Egypt, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia had oil wealth and prestige as the land of Mecca and Medina, the two holiest cities of Islam. To use Islam as a counterweight to Nasser's Arab socialism, Saudi Arabia sponsored an international Islamic conference in Mecca in 1962. It created the Muslim World League, dedicated to spreading Islam and fostering Islamic solidarity. The League was "extremely effective" in promoting Islam, particularly conservative Wahhabi Islam, and also served to combat "radical alien ideologies" (such as Arab socialism) in the Muslim world.[10]

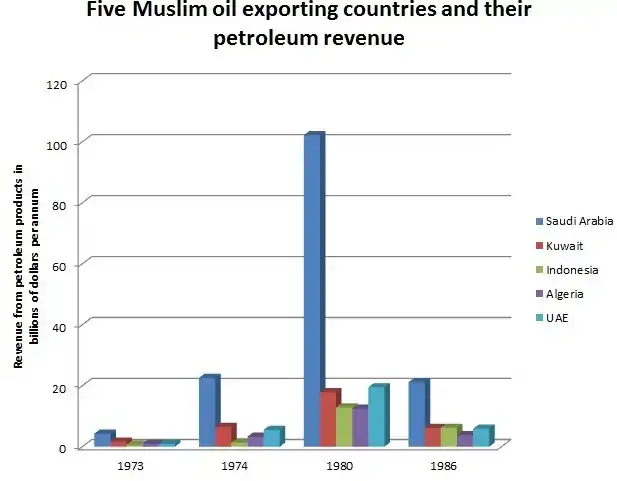

Years were chosen to shown revenue for before (1973) and after (1974) the October 1973 War, after the Iranian Revolution (1978-1979), and during the market turnaround in 1986.[11] Iran and Iraq are excluded because their revenue fluctuated due to the revolution and the war between them.[12]

Particularly after the Six-Day War, Islamic revival strengthened throughout the Arab world. After Nasser's death in 1970, his successor, Anwar Sadat, emphasized religion and economic liberalization rather than Arab nationalism and socialism. In Egypt's "shattering" 1967 defeat,[13] "Land, Sea and Air" had been the military slogan; in the perceived victory of the October 1973 war, it was replaced with the Islamic battle cry of Allahu Akbar.[14] While the October 1973 war was started by Egypt and Syria to take back the land conquered in 1967 by Israel, according to the French political scientist Gilles Kepel the "real victors" of the war were the Arab "oil-exporting countries", whose embargo against Israel's Western allies stopped Israel's counter-offensive.[15] The embargo's political success enhanced the prestige of the embargo-ers and the reduction in the global supply of oil sent oil prices soaring (from US$3 per barrel to nearly $12)[16] and with them, oil exporter revenues. This put Arab oil-exporting states in a "clear position of dominance within the Muslim world".[15] The most dominant was Saudi Arabia, the largest exporter by far (see bar chart above).[15]

In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood, which had been suppressed by the Egyptian government and aided by Saudi Arabia, was allowed to publish a monthly magazine, and its political prisoners were gradually released.[17] At universities, Islamists[18] took control and drove (anti-Sadat) student leftist and Pan-Arabist organizations underground.[19] By the late 1970s, Sadat called himself 'The Believer President'. He banned most sales of alcohol and ordered Egypt's state-run television to interrupt programs with salat (Islamic call to prayer) on the screen five times a day and to increase religious programming.[20]

See also

Notes

- Some sources say 1990

References

- Gold, Dore (2003). Hatred's Kingdom. Washington, DC: Regnery. p. 75.

Even before he became king, Faisal turned to Islam as a counterweight to Nasser's Arab socialism. The struggle between the two leaders became an Arab cold war, pitting the new Arab republics against the older Arab kingdoms.

- Writings by Malcolm H. Kerr

- The Arab Cold War, 1958–1964: A Study of Ideology in Politics. London: Chattam House Series, Oxford University Press, 1965.

- The Arab Cold War, 1958–1967: A Study of Ideology in Politics, 1967

- The Arab Cold War: Gamal 'Abd al-Nasir and His Rivals, 1958–1970, 3rd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Water Resources in Jordan: Evolving Policies for Development, the Environment, and Conflict Resolution, p.250

- Bahgat Korany, The Arab States in the Regional and International System: II. Rise of New Governing Elite and the Militarization of the Political System (Evolution) at Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs

- Aburish, Said K. (2004), Nasser, the Last Arab, New York City: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-28683-5, p.35–39

- Gold, Dore (2003). Hatred's Kingdom. Washington, DC: Regnery. p. 75.

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos (2016-07-02). "Nasser's Educators and Agitators across al-Watan al-'Arabi: Tracing the Foreign Policy Importance of Egyptian Regional Migration, 1952–1967" (PDF). British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 43 (3): 324–341. doi:10.1080/13530194.2015.1102708. ISSN 1353-0194. S2CID 159943632. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-20. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- Internal Security in Saudi Arabia, United Kingdom, Public Record Office, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, FC08/1483, 1970

- "Beginning to Face Defeat". Time. 1967-09-08. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- Gold, Dore (2003). Hatred's Kingdom. Washington, DC: Regnery. p. 75–76.

- source: Ian Skeet, OPEC: Twenty-Five Years of Prices and Politics (Cambridge: University Press, 1988)

- Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.75

- Murphy, Caryle, Passion for Islam: Shaping the Modern Middle East: the Egyptian Experience, (Simon and Schuster, 2002, p.31)

- Wright, Robin (2001) [1985]. Sacred Rage: The Wrath of Militant Islam. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 64–67. ISBN 0-7432-3342-5.

- Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. New York: I.B. Tauris. p. 69. ISBN 9781845112578.

The war of October 1973 was started by Egypt with the aim of avenging the humiliation of 1967 and restoring the lost legitimacy of the two states' ... [Egypt and Syria] emerged with a symbolic victory ... [but] the real victors in this war were the oil-exporting countries, above all Saudi Arabia. In addition to the embargo's political success, it had reduced the world supply of oil and sent the price per barrel soaring. In the aftermath of the war, the oil states abruptly found themselves with revenues gigantic enough to assure them a clear position of dominance within the Muslim world.

- "The price of oil – in context". CBC News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- Kepel, Gilles. Muslim Extremism in Egypt; the Prophet and Pharoh, Gilles Kepel, p.103–04

- particularly al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya

- Kepel, Gilles. Muslim Extremism in Egypt: The Prophet and Pharoh, Gilles Kepel, 1985, p.129

- Murphy, Caryle, Passion for Islam: Shaping the Modern Middle East: The Egyptian Experience, Simon and Schuster, 2002, p.36