Assamese alphabet

The Assamese alphabet or Assamese script,[2] is a writing system of the Assamese language. This script was also used in Assam and nearby regions for Sanskrit as well as other languages such as Bodo (now Devanagari), Khasi (now Roman), Mising (now Roman), Jaintia (now Roman) etc. It evolved from Kamarupi script. The current form of the script has seen continuous development from the 5th-century Umachal/Nagajari-Khanikargaon rock inscriptions written in an eastern variety of the Gupta script, adopting significant traits from the Siddhaṃ script in the 7th century. By the 17th century three styles of Assamese script could be identified (baminiya, kaitheli and garhgaya)[3] that converged to the standard script following typesetting required for printing. The present standard is identical to the Bengali alphabet except for two letters, ৰ (ro) and ৱ (vo); and the letter ক্ষ (khya) has evolved into an individual consonant by itself with its own phonetic quality whereas in the Bengali alphabet it is a conjugate of two letters.

| Assamese alphabet Ôxômiya lipi, অসমীয়া লিপি | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Languages | Assamese |

Time period | 8th century to the present |

Parent systems | |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

The Buranjis were written during the Ahom dynasty in the Assamese language using the Assamese alphabet. In the 14th century Madhava Kandali used Assamese script to compose the famous Saptakanda Ramayana, which is the first translation of Ramayana in a regional language after Valmiki's Ramayana in Sanskrit. Later, Sankardev used it in the 15th and 16th centuries to compose his oeuvre in Assamese and Brajavali dialect, the literary language of the bhakti poems (borgeets) and dramas.

The Ahom king Supangmung (1663–1670) was the first ruler who started issuing Assamese coins for his kingdom. Some similar scripts with minor differences are used to write Maithili, Bengali, Meithei and Sylheti.

History

The Umachal rock inscription of the 5th century evidences the first use of a script in the region. The script was very similar to the one used in Samudragupta's Allahabad Pillar inscription. Rock and copper plate inscriptions from then onwards, and Xaansi bark manuscripts right up to the 18th–19th centuries show a steady development of the Assamese script. The script could be said to develop proto-Assamese shapes by the 13th century. In the 18th and 19th century, the Assamese script could be divided into three varieties: Kaitheli (also called Lakhari in Kamrup region, used by non-Brahmins), Bamuniya (used by Brahmins, for Sanskrit) and Garhgaya (used by state officials of the Ahom kingdom)—among which the Kaitheli style was the most popular, with medieval books (like the Hastir-vidyrnava) and sattras using this style.[4] In the early part of the 19th century, Atmaram Sarmah designed the first Assamese script for printing in Serampore, and the Bengali and Assamese lithography converged to the present standard that is used today.

Assamese symbols

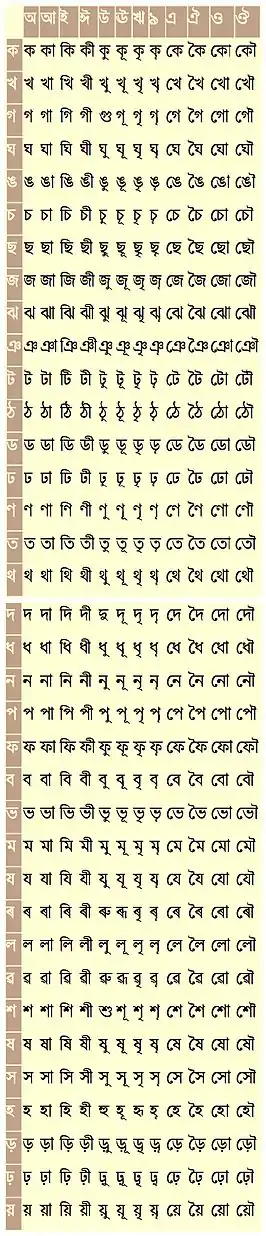

Vowels

The script presently has a total of 11 vowel letters, used to represent the eight main vowel sounds of Assamese, along with a number of vowel diphthongs. All of these are used in both Assamese and Bengali, the two main languages using the script. In addition to the vowel system in the Bengali alphabet the Assamese alphabet has an additional "matra" (ʼ) that is used to represent the phonemes অʼ and এʼ. Some of the vowel letters have different sounds depending on the word, and a number of vowel distinctions preserved in the writing system are not pronounced as such in modern spoken Assamese or Bengali. For example, the Assamese script has two symbols for the vowel sound [i] and two symbols for the vowel sound [u]. This redundancy stems from the time when this script was used to write Sanskrit, a language that had a short [i] and a long [iː], and a short [u] and a long [uː]. These letters are preserved in the Assamese script with their traditional names of hôrswô i (lit. 'short i') and dirghô i (lit. 'long i'), etc., despite the fact that they are no longer pronounced differently in ordinary speech.

Vowel signs can be used in conjunction with consonants to modify the pronunciation of the consonant (here exemplified by ক, kô). When no vowel is written, the vowel অ (ô or o) is often assumed. To specifically denote the absence of a vowel, (্) may be written underneath the consonant.

| Letter | Name of letter | Vowel sign with [kɔ] (ক) | Name of vowel sign | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| অ | o | ক (none) | (none) | ko | kɔ |

| অ or অʼ | ó | ক (none) or কʼ | urdho-comma | kó | ko |

| আ | a | কা | akar | ka | ka |

| ই | hroswo i | কি | hôrswôikar | ki | ki |

| ঈ | dirgho i | কী | dirghoikar | ki | ki |

| উ | hroswo u | কু | hroswoukar | ku | ku |

| ঊ | dirgho u | কূ | dirghoukar | ku | ku |

| ঋ | ri | কৃ | rikar | kri | kri |

| এ | e | কে | ekar | kê and ke | kɛ and ke |

| ঐ | oi | কৈ | ôikar | koi | kɔɪ |

| ও | ü | কো | ükar | kü | kʊ |

| ঔ | ou | কৌ | oukar | kou | kɔʊ |

Consonants

The names of the consonant letters in Assamese are typically just the consonant's main pronunciation plus the inherent vowel ô. Since the inherent vowel is assumed and not written, most letters' names look identical to the letter itself (e.g. the name of the letter ঘ is itself ঘ ghô). Some letters that have lost their distinctive pronunciation in Modern Assamese are called by a more elaborate name. For example, since the consonant phoneme /n/ can be written ন, ণ, or ঞ (depending on the spelling of the particular word), these letters are not simply called no; instead, they are called ন dontiya no ("dental n"), ণ murdhoinno no ("retroflex n"), and ঞ nio. Similarly, the phoneme /x/ can be written as শ taloibbo xo ("palatal x"), ষ murdhoinno xo ("retroflex x"), or স dontia xo ("dental x"), the phoneme /s/ can be written using চ prothom sô ("first s") or ছ ditio so ("second s"), and the phoneme /z/ can be written using জ borgia zo ("row z" = "the z included in the five rows of stop consonants") or য ontostho zo ("z situated between" = "the z that comes between the five rows of stop consonants and the row of sibilants"), depending on the standard spelling of the particular word.

| Letter | Name of Letter | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| ক | ko | k | k |

| খ | kho | kh | kʱ |

| গ | go | g | ɡ |

| ঘ | gho | gh | ɡʱ |

| ঙ | uŋo | ng | ŋ |

| চ | prothom so | s | s |

| ছ | ditio so | s | s |

| জ | borgiya zo | z | z |

| ঝ | zho | zh | z |

| ঞ | nio | y | ̃, n |

| ট | murdhoinno to | t | t |

| ঠ | murdhoinno tho | th | tʰ |

| ড | murdhoinno do | d | d |

| ঢ | murdhoinno dho | dh | dʱ |

| ণ | murdhoinnya no | n | n |

| ত | dontia to | t | t |

| থ | dontia tho | th | tʰ |

| দ | dontia do | d | d |

| ধ | dontia dho | dh | dʱ |

| ন | dontia no | n | n |

| প | po | p | p |

| ফ | pho | ph and f | pʰ~ɸ |

| ব | bo | b | b |

| ভ | bho | bh and vh | bʱ~β |

| ম | mo | m | m |

| য | ontostho zo | z | z |

| ৰ | ro | r | ɹ |

| ল | lo | l | l |

| ৱ | wo | w | w~β |

| শ | taloibbo xo | x and s | x~s |

| ষ | murdhoinno xo | x and s | x~s |

| স | dontia xo | x and s | x~s |

| হ | ho | h | ɦ~h |

| ক্ষ | khyo | khy, kkh | kʰj |

| ড় | dore ro | r | ɹ |

| ঢ় | dhore ro | rh | ɹɦ |

| য় | ontostho yô | y | j |

Assamese or Asamiya consonants include thirty three pure consonant letters in Assamese alphabet and each letter represents a single sound with an inherent vowel, the short vowel /a /.

The first twenty-five consonants letters are called sporxo borno. These sporxo bornos are again divided into five borgos. Therefore, these twenty-five letters are also called borgio borno.

The Assamese consonants are typically just the consonant's main pronunciation plus the inherent vowel o. The inherent vowel is assumed and not written, thus, names of most letters look identical to the letter itself (e.g. the name of the letter ঘ is itself ঘ gho).

Some letters have lost their distinctive pronunciation in modern Assamese are called by a more elaborate name. For example, since the consonant phoneme /n/ can be written ন, ণ, or ঞ (depending on the spelling of the particular word), these letters are not simply called no; instead, they are called ন dointo no ("dental n"), ণ murdhoinno no ("cerebral n"), and ঞ nio.

Similarly, the phoneme /x/ can be written as শ taloibbo xo ("palatal x"), ষ murdh9inno xo ("cerebral x"), or স dointo xo ("dental x"), the phoneme /s/ can be written using চ prothom so ("first s") or ছ ditio so ("second s"), and the phoneme /z/ can be written using জ borgio zo ("row z" = "the z included in the five rows of stop consonants") or য ontostho zo ("z situated between" = "the z that comes between the five rows of stop consonants and the row of sibilants"), depending on the standard spelling of the particular word.

The consonants can be arranged in following groups:

Group: 1 - Gutturals

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| ক | kô |

| খ | khô |

| গ | gô |

| ঘ | ghô |

| ঙ | ṅgô |

Group: 2 - Palatals

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| চ | prôthôm sô |

| ছ | ditiyô sô |

| জ | bôrgiya ja |

| ঝ | jhô |

| ঞ | ñiô |

Group: 3 - Cerebrals or Retroflex

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| ট | murdhôinnya ṭa |

| ঠ | murdhôinnya ṭha |

| ড | murdhôinnya ḍa |

| ড় | daré ṛa |

| ঢ | murdhôinnya ḍha |

| ঢ় | dharé ṛha |

| ণ | murdhôinnya ṇa |

Group: 4 - Dentals

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| ত | dôntiya ta |

| ৎ | khanda ṯ |

| থ | dôntiya tha |

| দ | dôntiya da |

| ধ | dôntiya dha |

| ন | dôntiya na |

Group: 5 - Labials

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| প | pa |

| ফ | pha |

| ব | ba |

| ভ | bha |

| ম | ma |

Group: 6 - Semivowels

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| য | ôntôsthô zô |

| য় | ôntôsthô ẏô |

| ৰ | ra |

| ল | la |

| ৱ | wa |

Group: 7 - Sibilants

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| শ | talôibbya xô |

| ষ | mudhôinnya xô |

| স | dôntiya xô |

Group: 8 - Aspirate

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| হ | ha |

| ক্ষ | khyô |

Group: 9 - Anuxāra

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| ং | ṃ anuxar |

Group: 9 - Bixarga

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| ঃ | ḥ bixarga |

Group: 10 - Candrabindu (anunāsika)

| Consonants | Phonetics |

|---|---|

| ঁ | n̐, m̐ candrabindu |

- The letters শ (talôibbya xô), ষ (murdhôinnya xô), স (dôntiya xô) and হ (hô) are called usma barna

- The letters য (za), ৰ (ra), ল (la) and ৱ (wa) are called ôntôsthô barna

- The letters ড় (daré ṛa) and ঢ় (dharé ṛha) are phonetically similar to /ra/

- The letter য (ôntôsthô zô) is articulated like 'ôntôsthô yô' in the word medial and final position. To denote the ôntôsthô ẏô, the letter য় (ôntôsthô ẏô) is used in Assamese

- ৎ (khanda ṯ) means the consonant letter Tö (dôntiya ta) without the inherent vowel

Halant

To write a consonant without the inherent vowel the halant sign is used below the base glyph. In Assamese this sign is called haxanta. (্)

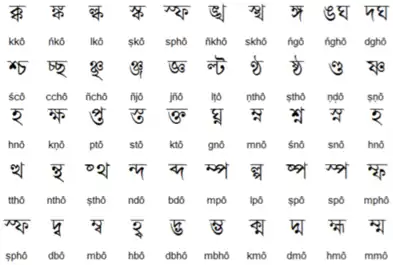

Consonant Conjuncts

In Assamese, the combination of three consonants is possible without their intervening vowels. There are about 122 conjunct letters. A few conjunct letters are given below:

Anuxôr

Anuxôr ( ং ) indicates a nasal consonant sound (velar). When an anuxar comes before a consonant belonging to any of the 5 bargas, it represents the nasal consonant belonging to that barga.

Candrabindu

Chandrabindu ( ঁ ) denotes nasalization of the vowel that is attached to it .

Bixargô

Bixargô ( ঃ ) represents a sound similar to /h /.

Consonant clusters according to Goswami

According to Dr. G. C. Goswami the number of two-phoneme clusters is 143 symbolised by 174 conjunct letters. Three phoneme clusters are 21 in number, which are written by 27 conjunct clusters. A few of them are given hereafter as examples:

| Conjunct letters | Transliteration | [Phoneme clusters (with phonetics) |

|---|---|---|

| ক + ক | (kô + kô) | ক্ক kkô |

| ঙ + ক | (ŋô + kô) | ঙ্ক ŋkô |

| ল + ক | (lô + kô) | ল্ক lkô |

| স + ক | (xô + kô) | স্ক skô |

| স + ফ | (xô + phô) | স্ফ sphô |

| ঙ + খ | (ŋô + khô) | ঙ্খ ŋkhô |

| স + খ | (xô + khô) | স্খ skhô |

| ঙ + গ | (ŋô + gô) | ঙ্গ ŋgô |

| ঙ + ঘ | (ŋô + ghô) | ঙ্ঘ ŋghô |

| দ + ঘ | (dô + ghô) | দ্ঘ dghô |

| শ + চ | (xô + sô) | শ্চ ssô |

| চ + ছ | (sô + shô) | চ্ছ sshô |

| ঞ + ছ | (ñô + shô) | ঞ্ছ ñshô |

| ঞ + জ | (ñô + zô) | ঞ্জ ñzô |

| জ + ঞ | (zô + ñô) | জ্ঞ zñô |

| ল + ট | (lô + ṭô) | ল্ট lṭô |

| ণ + ঠ | (ṇô + ṭhô) | ণ্ঠ ṇṭhô |

| ষ + ঠ | (xô + ṭhô) | ষ্ঠ ṣṭhô |

| ণ + ড | (ṇô + ḍô) | ণ্ড ṇḍô |

| ষ + ণ | (xô + ṇô) | ষ্ণ ṣṇô |

| হ + ন | (hô + nô) | হ hnô |

| ক + ষ | (kô + xô) | ক্ষ ksô |

| প + ত | (pô + tô) | প্ত ptô |

| স + ত | (xô + tô) | স্ত stô |

| ক + ত | (kô + tô) | ক্ত ktô |

| গ + ন | (gô + nô) | গ্ন gnô |

| ম + ন | (mô + nô) | ম্ন mnô |

| শ + ন | (xô + nô) | শ্ন snô |

| স + ন | (xô + nô) | স্ন snô |

| হ + ন | (hô + nô) | হ্ন hnô |

| ত + থ | (tô + thô) | ত্থ tthô |

| ন + থ | (nô + thô) | ন্থ nthô |

| ষ + থ | (xô + thô) | ষ্থ sthô |

| ন + দ | (nô + dô) | ন্দ ndô |

| ব + দ | (bô + dô) | ব্দ bdô |

| ম + প | (mô + pô) | ম্প mpô |

| ল + প | (lô + pô) | ল্প lpô |

| ষ + প | (xô + pô) | ষ্প spô |

| স + প | (xô + pô) | স্প spô |

| ম + ফ | (mô + phô) | ম্ফ mphô |

| ষ + ফ | (xô + phô) | স্ফ sphô |

| দ + ব | (dô + bô) | দ্ব dbô |

| ম + ব | (mô + bô) | ম্ব mbô |

| হ + ব | (hô + bô) | হ্ব hbô |

| দ + ভ | (dô + bhô) | দ্ভ dbhô |

| ম + ভ | (mô + bhô) | ম্ভ mbhô |

| ক + ম | (kô + mô) | ক্ম kmô |

| দ + ম | (dô + mô) | দ্ম dmô |

| হ + ম | (hô + mô) | হ্ম hmô |

| ম + ম | (mô + mô) | ম্ম mmô |

Digits

| Hindu-Arabic numerals | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assamese numerals | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | ১০ |

| Assamese names | xuinno | ek | dui | tini | sari | pas | soy | xat | ath | no (noy) | doh |

| শূণ্য | এক | দুই | তিনি | চাৰি | পাচ | ছয় | সাত | আঠ | ন (নয়) | দহ |

Three distinct variations of Assamese script from the Bengali

| Letter | Name of letter | Transliteration | IPA | Bengali |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ৰ | rô | r | ɹ | – bôesunnô rô |

| ৱ | wô | w | w | – (antasthya a) |

| ক্ষ | khyô | khy | kʰj | – juktokkhyô |

Though ক্ষ is used in Bengali as a conjunct letter. Cha or Chha too has different pronunciation.

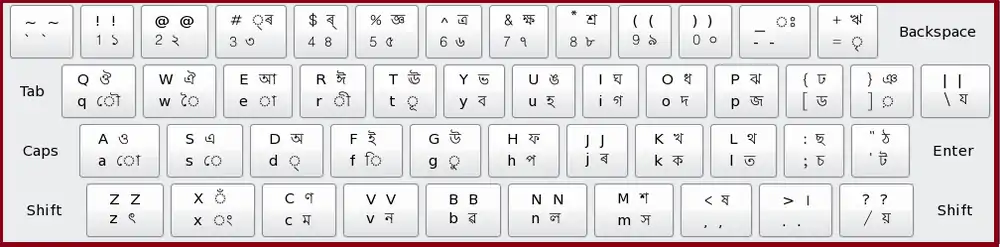

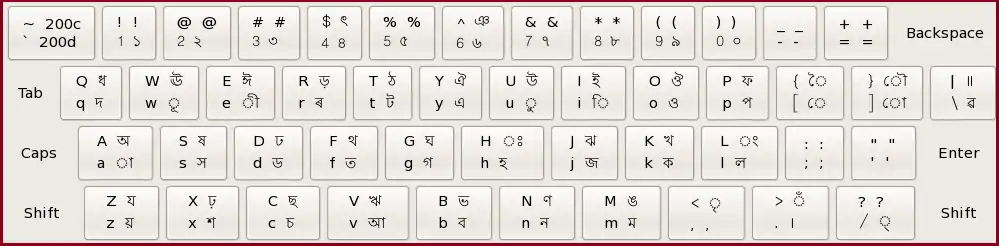

Assamese keyboard layout

- Inscript keyboard layout:

- Phonetic keyboard layout:

- The unique letter identifiers:

The keyboard locations of three characters unique to the Assamese script are depicted below:

.png.webp)

- ITRANS characterisation:

The "Indian languages TRANSliteration" (ITRANS) the ASCII transliteration scheme for Indic scripts here, Assamese; the characterisations are given below:

|

|

|

|

|

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Assamese of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

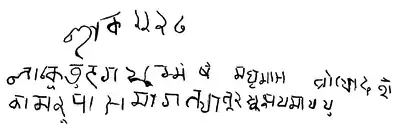

Assamese in Assamese alphabet

- ১ম অনুচ্ছেদ: জন্মগতভাৱে সকলো মানুহ মৰ্য্যদা আৰু অধিকাৰত সমান আৰু স্বতন্ত্ৰ। তেওঁলোকৰ বিবেক আছে, বুদ্ধি আছে। তেওঁলোকে প্ৰত্যেকে প্ৰেত্যেকক ভ্ৰাতৃভাৱে ব্যৱহাৰ কৰা উচিত।[5]

Assamese in WRA Romanisation

- Prôthôm ônussêd: Zônmôgôtôbhawê xôkôlû manuh môrjyôda aru ôdhikarôt xôman aru sôtôntrô. Têû̃lûkôr bibêk asê, buddhi asê. Têû̃lûkê prôittêkê prôittêkôk bhratribhawê byôwôhar kôra usit.

Assamese in SRA Romanisation

- Prothom onussed: Jonmogotobhabe xokolü manuh moirjjoda aru odhikarot xoman aru sotontro. Teü̃lükor bibek ase, buddhi ase. Teü̃lüke proitteke proittekok bhratribhawe bebohar kora usit.

Assamese in SRA2 Romanisation

- Prothom onussed: Jonmogotovawe xokolu’ manuh morjjoda aru odhikarot xoman aru sotontro. Teulu’kor bibek ase, buddhi ase. Teulu’ke proitteke proittekok vratrivawe bewohar kora usit.

Assamese in CCRA Romanisation

- Prothom onussed: Jonmogotobhawe xokolu manuh morjyoda aru odhikarot xoman aru sotontro. Teulukor bibek ase, buddhi ase. Teuluke proitteke proittekok bhratribhawe byowohar kora usit.

Assamese in IAST Romanisation

- Prathama anucchēda: Janmagatabhāve sakalo mānuha maryadā āru adhikārata samāna āru svatantra. Tēõlokara bibēka āchē, buddhi āchē. Tēõlokē pratyēkē pratyēkaka bhrātribhāvē byavahāra karā ucita.

Assamese in the International Phonetic Alphabet

- /pɹɒtʰɒm ɒnussɛd | zɒnmɒɡɒtɒbʰaβɛ xɒkɒlʊ manuʱ mɔɪdʑdʑɒda aɹu ɔdʰikaɹɒt xɒman aɹu sɒtɒntɹɒ || tɛʊ̃lʊkɒɹ bibɛk asɛ buddʰi asɛ || tɛʊ̃lʊkɛ pɹɔɪttɛkɛ pɹɔɪttɛkɒk bʰɹatɹibʰaβɛ bɛβɒɦaɹ kɒɹa usit/

Gloss

- 1st Article: Congenitally all human dignity and right-in equal and free. their conscience exists, intellect exists. They everyone everyone-to brotherly behaviour to-do should.

Translation

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Unicode

The Bengali–Assamese script was added to the Unicode Standard in October 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

The Unicode block for Assamese and Bengali is U+0980–U+09FF:

| Bengali[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+098x | ঀ | ঁ | ং | ঃ | অ | আ | ই | ঈ | উ | ঊ | ঋ | ঌ | এ | |||

| U+099x | ঐ | ও | ঔ | ক | খ | গ | ঘ | ঙ | চ | ছ | জ | ঝ | ঞ | ট | ||

| U+09Ax | ঠ | ড | ঢ | ণ | ত | থ | দ | ধ | ন | প | ফ | ব | ভ | ম | য | |

| U+09Bx | র | ল | শ | ষ | স | হ | ় | ঽ | া | ি | ||||||

| U+09Cx | ী | ু | ূ | ৃ | ৄ | ে | ৈ | ো | ৌ | ্ | ৎ | |||||

| U+09Dx | ৗ | ড় | ঢ় | য় | ||||||||||||

| U+09Ex | ৠ | ৡ | ৢ | ৣ | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | ||

| U+09Fx | ৰ | ৱ | ৲ | ৳ | ৴ | ৵ | ৶ | ৷ | ৸ | ৹ | ৺ | ৻ | ৼ | ৽ | ৾ | |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

- Assamese Braille

- Help:IPA for Assamese

- Romanisation of Assamese

Hamkh

- "In fact, the term 'Eastern Nagari' seems to be the only designation which does not favour one or the other language. However, it is only applied in academic discourses, whereas the name 'Bengali script' dominates the global public sphere." (Brandt 2014:25)

- The name ăcãmăkṣara first appears in Ahom coins and copperplates where the name denoted the Ahom script (Bora 1981:11–12)

- (Bora 1981:53)

- (Neog 1980, p. 308)

- https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/asm.pdf

References

- Bora, Mahendra (1981). The Evolution of Assamese Script. Jorhat, Assam: Assam Sahitya Sabha.

- Neog, Maheshwar (1980). Early History of the Vaishnava Faith and Movement in Assam. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.

- "Assamese literature – An overview and historical perspective Linking into broader Indian canvas". Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- "Assamese writing System". Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- "Antiques reveal script link – Inscriptions on 3 copper plates open new line of research". The Telegraph (Kolkata). 25 January 2006. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2007.