Berkeley County, West Virginia

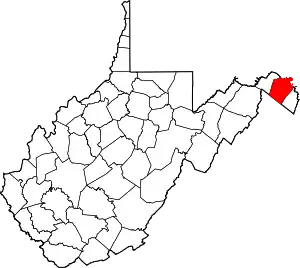

Berkeley County is located in the Shenandoah Valley in the Eastern Panhandle region of West Virginia in the United States. The county is part of the Hagerstown-Martinsburg, MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Berkeley County | |

|---|---|

Bedinger Mill at Lick Run Plantation, Bedington, West Virginia. | |

Location within the U.S. state of West Virginia | |

West Virginia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 39°28′N 78°02′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | May 15, 1772 |

| Seat | Martinsburg |

| Largest city | Martinsburg |

| Area | |

| • Total | 322 sq mi (830 km2) |

| • Land | 321 sq mi (830 km2) |

| • Water | 0.4 sq mi (1 km2) 0.1%% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 104,169 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 119,171 |

| • Density | 320/sq mi (120/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

| Website | www |

As of the 2010 census, the county population was 104,169,[1] making it the second-most populous of West Virginia's 55 counties, behind Kanawha. The City of Martinsburg is the county seat.

History

Created on May 15, 1772[2] by an act[3] of House of Burgesses from the northern third of Frederick County when it was part of Virginia, Berkeley County became West Virginia's second-oldest county after it separated from Virginia in 1863, during the Civil War. At the time of the county's formation, Berkeley County comprised areas that now are part of present-day Jefferson and Morgan counties in West Virginia.

Most historians believe the county was named for Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt (1718–1770), Colonial Governor of Virginia from 1768 to 1770. West Virginia's Blue Book, for example, indicates Berkeley County was named in his honor. He served as a colonel in England's North Gloucestershire militia in 1761, and represented that division of the county in Parliament until he was made a peer in 1764.[4] Having incurred heavy gambling debts, he solicited a government appointment and in July 1768, was made Governor of Virginia. In 1769, he reluctantly dissolved the House of Burgesses after it adopted resolutions opposing parliament's replacement of requisitions with parliamentary taxes as a means of generating revenue and a requirement the colonists send accused criminals to England for trial.

Despite his differences with the House of Burgesses, Berkeley was well respected by the colonists, especially after he sent Parliament letters encouraging it to repeal the taxes. When Parliament refused to rescind them, Governor Berkeley requested to be recalled. In appreciation of his efforts, the colonists erected a monument to his memory which stands in Williamsburg, and two counties were later named in his honor: Berkeley in present-day West Virginia and Botetourt in Virginia.

Other historians claim Berkeley County may have been named in honor of Sir William Berkeley (1610–1677), who was born near London, graduated from Oxford University in 1629 and was appointed Governor of Virginia in 1642. He served as Governor until 1652 and was reappointed Governor in 1660. Berkeley presided over the colony during Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676, and was called back to England the following year.

The first settlers

According to missionary reports, several thousand Hurons occupied present-day West Virginia, including the Eastern Panhandle region, during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. During the 17th century, the Iroquois Confederacy (then consisting of the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, Oneida, and Seneca tribes) drove the Hurons from the state. The Iroquois Confederacy was headquartered in New York and was not interested in occupying present-day West Virginia. Instead, they used it as a hunting ground during the spring and summer months.

During the early 18th century, West Virginia's Eastern Panhandle region was inhabited by the Tuscarora. They eventually migrated northward into New York and, in 1712, became the sixth nation to be formally admitted into the Iroquois Confederacy. The Eastern Panhandle region was also used as a hunting ground by several other Indian tribes, including the Shawnee (then known as the Shawanese) who resided near present-day Winchester, Virginia and Moorefield, West Virginia until 1754 when they migrated into Ohio. The Mingo, who resided in the Tygart Valley and along the Ohio River in present-day West Virginia's Northern Panhandle region, and the Delaware, who lived in present-day eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, but had several autonomous settlements as far south as present-day Braxton County, also used the area as a hunting ground.

Following the French and Indian War, the Mingo retreated to their homes along the banks of the Ohio River and were rarely seen in the Eastern Panhandle region. Although the French and Indian War was over, many Indians continued to view the British as a threat to their sovereignty and continued to fight them. In the summer of 1763, Pontiac, an Ottawa chief, led raids on key British forts in the Great Lakes region. Shawnee chief Keigh-tugh-qua, also known as Cornstalk, led similar attacks on western Virginia settlements, starting with attacks in present-day Greenbrier County and extending northward to Berkeley Springs, and into the northern Shenandoah Valley. By the end of July, Indians had destroyed or captured all British forts west of the Alleghenies except Fort Detroit, Fort Pitt, and Fort Niagara. The uprisings were ended on August 6, 1763 when British forces, under the command of Colonel Henry Bouquet, defeated Delaware and Shawnee forces at Bushy Run in western Pennsylvania.

During the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the Mingo and Shawnee, headquartered at Chillicothe, allied themselves with the British. In 1777, a party of 350 Wyandots, Shawnees and Mingos, armed by the British, attacked Fort Henry, near present-day Wheeling. Nearly half of the soldiers manning the fort were killed in the three-day assault. The Indians then left the area celebrating their victory. For the remainder of the war, smaller raiding parties of Mingo, Shawnee, and other Indian tribes terrorized settlers throughout northern and eastern West Virginia. As a result, European settlement throughout present-day West Virginia, including the Eastern Panhandle, came to a virtual standstill until the war's conclusion.

Following the war, the Mingo and Shawnee, once again allied with the losing side, returned to their homes. As the number of settlers in present-day West Virginia began to grow, both the Mingo and Shawnee moved further inland, leaving their traditional hunting ground to the white settlers.

17th-century European explorers

In 1670, John Lederer, a German physician and explorer employed by Sir William Berkeley, colonial governor of Virginia, became the first European to set foot in present-day Berkeley County; their safety was not guaranteed. John Howard and his son also passed through present-day Berkeley County a few years later, and discovered the valley of the South Branch Potomac River at Green Spring.

The 18th century

The next known explorer to traverse the county was John Van Meter (1683–1745) in the 1730s. He came across the Potomac River, at what is now known as Shepherdstown, then he made his way to the South Branch Potomac River. In 1726, Morgan Morgan moved from Delaware and founded the first permanent English settlement of record in West Virginia on Mill Creek near the present-day Bunker Hill in Berkeley County. The state of West Virginia erected a monument in Bunker Hill commemorating the event, and placed a marker at Morgan's grave, which is located in a cemetery near the park. Morgan Morgan and his wife, Catherine Garretson, had eight children. His son, Zackquill Morgan, later founded present-day Morgantown.

In 1730, John Van Meter, with his brother Isaac (1692–1757),[5] secured a patent for 40,000 acres (160 km2) at the South Branch Potomac River, much of it in present-day Berkeley County, from Virginia's Colonial Lieutenant Governor William Gooch. Part of the land was sold the following year to Hans Yost Heydt, also known as Joist Hite or Jost Hite. In 1732, Heydt (Hite) and fifteen families set out from York, Pennsylvania, passed through present-day Berkeley County, and settled near present-day Winchester, Virginia. In 1744 Isaac Van Meter moved to a site near Moorefield — then part of Hampshire County, but now in Hardy County (see Fort Pleasant) — where he was later scalped and killed by Indians. (His brother John settled and died in Winchester, Virginia.)

In 1748, George Washington, then just sixteen years old, surveyed present-day Berkeley County for Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron. He later returned to Bath (Berkeley Springs), West Virginia several times over the next several years with his half-brother, Lawrence, who was ill and hoped that the warm springs might improve his health. The springs, and their rumored medicinal benefits, attracted numerous Native Americans as well as Europeans to the area.

The 19th century

Berkeley County was reduced in size twice during the 19th century. On January 8, 1801, Jefferson County was formed out of the county's eastern section. Then, on February 9, 1820, Morgan County was formed out of the county's western section and parts of Hampshire County.

Berkeley County was of strategic importance to both the North and the South during the American Civil War (from 1861 to 1865). The county, and Martinsburg, the county seat, lay at the northern edge of the Shenandoah Valley, and Martinsburg was very important because the main line of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad ran through the town. The rail line was of great importance to both armies. Also, Martinsburg was close to the Union arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Control over Martinsburg changed hands many times during the war, especially prior to the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. After Gettysburg, the city remained mostly under Union control.

Most of Berkeley County's residents were loyal to the South during the American Civil War. There were seven companies of soldiers recruited from the county: five for the Confederate Army and two for the Union Army.

Yet it was (then-Colonel) Stonewall Jackson who wrote to Robert E. Lee, "... I regret to say that in Berkeley things are growing worse, and that the threats from Union men are calculated to curb the expression of Southern feeling."[6]

A member of the Stonewall Brigade also wrote, "We left Winchester the first of this week and came to Berkeley County, the meanest Abolition hole on the face of the earth, Martinsburg especially."[7]

At least six hundred men from Berkeley County served in either the Confederate Army or the Union Army. When the vote for separation from Confederate Virginia was held, the majority voted for the Union creation of the state of West Virginia.

Berkeley County was also the home of Maria Isabella "Belle" Boyd, a famous spy for the Confederacy. She was born in Bunker Hill on May 9, 1844, moved to Martinsburg before 1850, and lived there until the outbreak of the war. Her espionage career began on July 4, 1861 when a band of drunken Union soldiers broke into her Martinsburg home intent on raising the United States flag over the house. As the soldiers forced their way into the house (one account has a soldier pushing Belle's mother), Belle drew a pistol and killed him. A board of inquiry exonerated her actions as justifiable homicide, but sentries were posted around the house and officers kept close track of her activities. She befriended the officers, and at least one of them, Captain Daniel Keily, shared military secrets with her. She conveyed those secrets to Confederate officers via her slave, Eliza Hopewell, who carried the messages in a hollowed-out watch case. She later moved to Front Royal, Virginia to live with an aunt. One evening in mid-May, 1862 General James Shields and his staff conferred in the parlor of the local hotel. Belle hid upstairs and overheard Shields mentioning that he had been ordered east, a move that would reduce the Union Army's strength at Front Royal. Belle reported the news to Colonel Turner Ashby, a Confederate scout. He relayed the information to General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, commander of the Confederate Army. After Jackson took Front Royal on May 23, he penned a note of gratitude to Belle, and named her a Captain and an honorary Aid de Camp. Belle was later arrested by the Union Army for espionage, spent a month in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C. and was freed in a prisoner exchange. In June 1863, she was arrested again for espionage by the Union Army during a visit to Martinsburg. She remained in the Old Carroll Prison in DC until December 1, 1863 when, suffering from typhoid, she was allowed to travel South to regain her strength. Later, she was running the sea blockade, was captured and under guard to Lt. Samuel Wylde Harding. He fell in love and asked Belle to marry him. She said she would if he helped her get the captains code book and let him escape. Also to join the Confederate army when he could, which he agreed to all. Belle was escorted and deported to Canada, told if she returned she would be shot. She then went to London, Samuel left the navy and also went to England. They had a large wedding in which the future King and ambassadors attended. While there, she began a stage career and penned her memoirs. After the war, she returned to the United States, Divorced Sam, and toured the western states recounting her exploits as a spy during the war. She died in 1900 in Evansville, Wisconsin. A group from the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) paid for her burial gown and funeral. Belle's 3rd husband (an actor) Belle and the GAR were in partnership.[8]

Joining West Virginia

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Berkeley and Jefferson counties, both lying on the Potomac River east of the mountains, with the consent of the Reorganized Government of Virginia, supposedly voted in favor of annexation to West Virginia in 1863. The occupying Federal troops in the area ensured the desired outcome. Many voters absent in the Confederate Army when the vote was taken refused to acknowledge the transfer upon their return. The Virginia General Assembly repealed the Act of Secession and in 1866 brought suit against West Virginia asking the court to declare the counties a part of Virginia. Meanwhile, Congress, on March 10, 1866, passed a joint resolution recognizing the transfer. In 1871, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Virginia v. West Virginia,[9] upholding the secession of West Virginia, including Berkeley and Jefferson counties, from Virginia.

In 1863, West Virginia's counties were divided into civil townships, with the intention of encouraging local government. This proved impractical in the heavily rural state, and in 1872 the townships were converted into magisterial districts.[10] Berkeley County was divided into seven districts: Arden, Falling Water, Gerardstown, Hedgesville, Martinsburg, Mill Creek, and Opequan.[lower-roman 1] The town of Martinsburg was originally co-extensive with Martinsburg District, but later spread into adjoining districts. Between 1990 and 2000, Berkeley County was redivided into six magisterial districts: Adam Stephens, Norborne, Potomac, Shenandoah, Tuscarora, and Valley.[11]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 322 square miles (830 km2), of which 321 square miles (830 km2) is land and 0.4 square miles (1.0 km2) (0.1%) is water.[12]

Mountains and hills

- Third Hill Mountain - highest and most topographically prominent peak in the county

Sleepy Creek Mountain

North Mountain

Rivers and streams

- Potomac River

- Back Creek

- Tilhance Creek

- Cherry Run

- Meadow Branch (tributary of Sleepy Creek in Morgan County)

- Opequon Creek

- Middle Creek

- Mill Creek

- Tuscarora Creek

Agricultural land and conservation easements

Berkeley County has 53 farmland easements which place permanent restrictions on development, covering 5,133 acres of land, according to the Berkeley County Farmland Protection Board.[13]

Adjacent counties

- Washington County, Maryland (north)

- Jefferson County (southeast)

- Frederick County, Virginia (south)

- Morgan County (northwest)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 19,713 | — | |

| 1800 | 22,006 | 11.6% | |

| 1810 | 11,479 | −47.8% | |

| 1820 | 11,211 | −2.3% | |

| 1830 | 10,518 | −6.2% | |

| 1840 | 10,972 | 4.3% | |

| 1850 | 11,771 | 7.3% | |

| 1860 | 12,525 | 6.4% | |

| 1870 | 14,900 | 19.0% | |

| 1880 | 17,380 | 16.6% | |

| 1890 | 18,702 | 7.6% | |

| 1900 | 19,469 | 4.1% | |

| 1910 | 21,999 | 13.0% | |

| 1920 | 24,554 | 11.6% | |

| 1930 | 28,030 | 14.2% | |

| 1940 | 29,016 | 3.5% | |

| 1950 | 30,359 | 4.6% | |

| 1960 | 33,791 | 11.3% | |

| 1970 | 36,356 | 7.6% | |

| 1980 | 46,846 | 28.9% | |

| 1990 | 59,253 | 26.5% | |

| 2000 | 75,905 | 28.1% | |

| 2010 | 104,169 | 37.2% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 119,171 | [14] | 14.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] 1790–1960[16] 1900–1990[17] 1990–2000[18] 2010-2019[1] | |||

2000 census

As of the census[19] of 2000, there were 75,905 people, 29,569 households, and 20,698 families residing in the county. The population density was 236 people per square mile (91/km2). There were 32,913 housing units at an average density of 102 per square mile (40/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 92.74% White, 4.69% Black or African American, 0.25% Native American, 0.46% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.56% from other races, and 1.28% from two or more races. 1.52% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 29,569 households, out of which 33.40% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.60% were married couples living together, 10.70% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.00% were non-families. 24.20% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.53 and the average family size was 2.99.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.70% under the age of 18, 8.30% from 18 to 24, 31.30% from 25 to 44, 23.60% from 45 to 64, and 11.20% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 99.10 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.40 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $38,763, and the median income for a family was $44,302. Males had a median income of $32,010 versus $23,351 for females. The per capita income for the county was $17,982. About 8.70% of families and 11.50% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.60% of those under age 18 and 10.10% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 104,169 people, 39,855 households, and 27,881 families residing in the county.[20] The population density was 324.4 inhabitants per square mile (125.3/km2). There were 44,762 housing units at an average density of 139.4 per square mile (53.8/km2).[21] The racial makeup of the county was 87.8% white, 7.1% black or African American, 0.8% Asian, 0.3% American Indian, 1.2% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 3.8% of the population.[20] In terms of ancestry, 27.0% were German, 14.8% were Irish, 12.3% were English, 10.2% were American, and 5.1% were Italian.[22]

Of the 39,855 households, 35.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.3% were married couples living together, 12.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 30.0% were non-families, and 23.4% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.04. The median age was 37.6 years.[20]

The median income for a household in the county was $52,857 and the median income for a family was $64,001. Males had a median income of $45,654 versus $34,239 for females. The per capita income for the county was $25,460. About 7.0% of families and 10.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.2% of those under age 18 and 6.5% of those age 65 or over.[23]

Government and public safety

County government

Berkeley County has an elected five member County Council. [24]

Berkeley County Sheriff

The Sheriff's Office operates the county jail, provides court protection, provides county building and facility security, and provides patrol and detective services for unincorporated areas of the county.[25] Martinsburg has a municipal police department.

Politics

After having leaned strongly towards the Democratic Party between the New Deal and Bill Clinton’s presidency, most of West Virginia has since 2000 seen a powerful swing towards the Republican Party due to declining unionization[26] and differences with the Democratic Party’s liberal views on social issues.[27] Berkeley County, in contrast, was in the majority opposed to secession at the Virginia Secession Convention[28][29] and has voted solidly Republican over most of the century and a half since, with the exception of Democratic landslides. No Democratic presidential candidate has carried Berkeley County since Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 64.6% 33,279 | 33.3% 17,186 | 2.1% 1,070 |

| 2016 | 65.1% 28,244 | 28.4% 12,321 | 6.5% 2,799 |

| 2012 | 59.4% 22,156 | 38.3% 14,275 | 2.4% 876 |

| 2008 | 55.7% 20,841 | 42.8% 15,994 | 1.5% 565 |

| 2004 | 63.0% 21,293 | 36.2% 12,244 | 0.7% 248 |

| 2000 | 59.2% 13,619 | 38.2% 8,797 | 2.6% 594 |

| 1996 | 47.9% 9,859 | 40.4% 8,321 | 11.6% 2,396 |

| 1992 | 45.6% 9,134 | 35.7% 7,159 | 18.7% 3,736 |

| 1988 | 62.8% 10,761 | 36.8% 6,313 | 0.4% 61 |

| 1984 | 67.5% 12,887 | 32.4% 6,181 | 0.1% 24 |

| 1980 | 57.0% 9,955 | 38.9% 6,783 | 4.1% 716 |

| 1976 | 52.1% 8,935 | 47.9% 8,216 | |

| 1972 | 70.8% 10,954 | 29.2% 4,523 | |

| 1968 | 49.9% 7,223 | 34.1% 4,929 | 16.0% 2,321 |

| 1964 | 38.7% 5,457 | 61.3% 8,628 | |

| 1960 | 54.2% 8,369 | 45.8% 7,072 | |

| 1956 | 61.6% 9,071 | 38.4% 5,649 | |

| 1952 | 53.4% 8,149 | 46.6% 7,111 | |

| 1948 | 46.9% 6,042 | 52.8% 6,797 | 0.3% 34 |

| 1944 | 51.4% 6,151 | 48.6% 5,819 | |

| 1940 | 43.1% 6,562 | 56.9% 8,658 | |

| 1936 | 44.0% 6,585 | 55.7% 8,336 | 0.3% 39 |

| 1932 | 47.1% 6,370 | 51.8% 7,009 | 1.1% 148 |

| 1928 | 70.3% 8,477 | 29.4% 3,540 | 0.4% 42 |

| 1924 | 53.2% 5,427 | 42.8% 4,366 | 4.0% 412 |

| 1920 | 54.0% 5,259 | 45.1% 4,399 | 0.9% 90 |

| 1916 | 48.1% 2,802 | 50.4% 2,938 | 1.5% 86 |

| 1912 | 25.0% 1,349 | 50.1% 2,703 | 24.8% 1,339 |

Communities

City

- Martinsburg (county seat)

Town

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

- Allensville

- Arden

- Baker Heights

- Baxter

- Bedington

- Berkeley

- Bessemer

- Blairton

- Bunker Hill

- Darkesville

- Douglas Grove

- Files Crossroad

- Ganotown

- Georgetown

- Gerrardstown

- Glengary

- Greensburg

- Grubbs Corner

- Hainesville

- Johnsontown

- Jones Springs

- Little Georgetown

- Marlowe

- Nipetown

- Nollville

- North Mountain

- Pikeside

- Ridgeway

- Scrabble

- Shanghai

- Spring Mills

- Swan Pond

- Tablers Station

- Tarico Heights

- Tomahawk

- Union Corner

- Van Clevesville

- Vanville

- Winebrenners Crossroad

- Wynkoop Spring

Magisterial districts

- Adam Stephens

- Norborne

- Potomac

- Shenandoah

- Tuscarora

- Valley

Notable people

- Victoria "Vicky" Bullett, former professional women's basketball player, member of the 1988 and 1992 U.S. Olympic Teams that won gold and bronze medals respectively.

- Christopher Martinka, an award-winning Scottish-American documentary photographer.[31]

- Thomas Hinds (1780 - 1840), a military hero of the War of 1812, US Congressman, and namesake of Hinds County, Mississippi.[32]

- William Robinson Leigh (1866 – 1955), an American artist who specialized in Western scenes, was born at Maidstone Manor.

See also

Footnotes

- Over time, Falling Water and Gerardstown came to be spelled "Falling Waters" and "Gerrardstown", but both spellings were in use for several decades.

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- "Hening's Statutes at Large, Vol. 8, Chapter XLIII". VAGenWeb. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ""An act for dividing the county of Frederick into three distinct counties" Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia 1770-1772". Internet Archive. Richmond: Printed by Thomas W. White. pp. 314–316. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- Berkeley claimed the title of Baron Botetourt as the lineal descendant of Maurice de Berkeley (d.1361) and his wife Catherine de Botetourt, sister & co-heir of John Botetourt, son and heir of Sir John de Botetourt (d.1324), baron by writ 1309-15. Maurice (d.1361) was the son and heir of Maurice de Berkeley (d.1347 at the Siege of Calais), who had acquired the manor of Stoke Gifford, Gloucestershire, in 1337, the second son of Maurice de Berkeley, 2nd Baron Berkeley (1271–1326).

- Their father was Joost Jansen Van Metern (or John Van Meter; 1656-1706) who had been born in Gelderland, the Netherlands and died in Salem County, New Jersey.

- The War of the Rebellion (Official Records), series 1, vol. 2, page 863; May 21, 1861

- Ted Barclay, 4th Va Inf., letter to his mother, June 22, 1861

- The Berkeley County, WV Historical Society

- Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39 (1871).

- Otis K. Rice & Stephen W. Brown, West Virginia: A History, 2nd ed., University Press of Kentucky, Lexington (1993), p. 240.

- United States Census Bureau, U.S. Decennial Census, Tables of Minor Civil Divisions in West Virginia, 1870–2010.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Hoffer, Audrey (August 2, 2017). "Farm community in West Virginia aims to be a model for restricting development". Washington Post. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- Berkeley County website

- Sheriff office website.

- Schwartzman, Gabe; ‘How Central Appalachia Went Right’; Daily Yonder, January 13, 2015

- Cohn, Nate; ‘Demographic Shift: Southern Whites’ Loyalty to G.O.P. Nearing That of Blacks to Democrats’, The New York Times, April 24, 2014

- Hinkle, Harlan H.; Grayback Mountaineers: The Confederate Face of Western Virginia, p. 176 ISBN 0595268404

- Brisbin, Richard A.; West Virginia Politics and Government, p. 107 ISBN 0803219369

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- [https://rps.org/portfolio/33728/Christopher-Martinka

- "Thomas Hinds," Jefferson County website, www.jeffersoncountyms.org/

Sources

- Aler, F. Vernon. 1888. Aler's History of Martinsburg and Berkeley County, West Virginia: From the Origin of the Indians ..., Hagerstown, MD: Mail Publishing Company

- Doherty, William T. Berkeley County, U.S.A.: A Bicentennial History of a Virginia and West Virginia County, 1772-1972. Parsons, WV: McClain Printing Company, 1972

- Evans, Willis F. History of Berkeley County, West Virginia. Wheeling, WV, 1928 (unknown publisher)

- Dilger, Dr. Robert Jay, Director, Institute for Public Affairs and Professor of Political Science at West Virginia University

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Berkeley County, West Virginia. |

_in_Nollville%252C_Berkeley_County%252C_West_Virginia.jpg.webp)