History of the Philippines (900–1565)

The history of the Philippines between 900 and 1565 begins with the creation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription in 900 and ends with Spanish colonisation in 1565. The inscription records its date of creation in the year 822 of the Hindu Saka calendar, corresponding to 900 AD in the Gregorian system. Therefore, the recovery of this document marks the end of prehistory of the Philippines at 900 AD. During this historical time period, the Philippine archipelago was home to numerous kingdoms and sultanates and was a part of the theorised Indosphere and Sinosphere.[1][2][3][4]

| |

| Horizon | Philippine history |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Southeast Asia |

| Period | c.900–1560s |

| Dates | c. Before 900 AD |

| Major sites | Tundun, Seludong, Pangasinan, Limestone tombs, Idjang citadels, Panay, Rajahnate of Cebu, Rajahnate of Butuan, Kota Wato, Kota Sug, Ma-i, Dapitan, Gold artifacts, Singhapala, Ifugao plutocracy |

| Characteristics | Indianized kingdoms, Hindu and Buddhist Nations, Islamized Indianized sultanates Sinicized Nations |

| Preceded by | Prehistory of the Philippines |

| Followed by | Colonial era |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Philippines |

|

| Timeline |

| Archaeology |

|

|

Sources of precolonial history include archeological findings, records from contact with the Song Dynasty, the Bruneian Empire, Japan, and Muslim traders, the genealogical records of Muslim rulers, accounts written by Spanish chroniclers in the 16th and 17th century, and cultural patterns which at the time had not yet been replaced through European influence.

Laguna Copperplate Inscription

Decipherment

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription measures around 20 cm by 30 cm and is inscribed with ten lines of writing on one side. The text was mostly written in Old Malay with influences of Sanskrit, Old Javanese and Old Tagalog using the Kawi script. Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma deciphered the text. The date of the inscription is in the "Year of Saka 822, month of Vaisakha", corresponding to April-May in 900 AD.

The text notes the acquittal of all descendants of a certain honourable Namwaran from a debt of 1 kati and 8 suwarna, equivalent to 926.4 grams of gold, granted by the Military Commander of Tundun (Tondo) and witnessed by the leaders of Pailah, Binwangan and Puliran, which are places likely also located in Luzon. The reference to the contemporaneous Medang Kingdom in modern-day Indonesia implies political connections with territories elsewhere in the Maritime Southeast Asia.

This document is the earliest record of a Philippine language and the presence of writing in the islands.[5]

Politics

City-states

Early settlements, referred to as barangays, ranged from 20 to 100 families on the coast, and around 150-200 people in more interior areas. Coastal settlements were connected over water, with much less contact occurring between highland and lowland areas.[6] By the 1300s, a number of the large coastal settlements had emerged as trading centers, and became the focal point of societal changes.[7] Some polities had exchanges with other states across Asia.[8][9][10][11][12]

Polities founded in the Philippines from the 10th–16th centuries include Maynila,[13] Tondo, Namayan, Pangasinan, Cebu, Butuan, Maguindanao, Lanao, Sulu, and Ma-i.[14] Among the nobility were leaders called "Datus," responsible for ruling autonomous groups called "barangay" or "dulohan".[7] When these barangays banded together, either to form a larger settlement[7] or a geographically looser alliance group,[8] the more esteemed among them would be recognized as a "paramount datu",[7][15] rajah, or sultan[16] which headed the community state.[17] There is little evidence of large-scale violence in the archipelago prior to the 2nd millennium AD,[18] and throughout these periods population density is thought to have been low.[19]

Social classes

The early polities were typically made up of three-tier social structure: a nobility class, a class of "freemen", and a class of dependent debtor-bondsmen:[7][8]

In Luzon

In the Cagayan Valley, the head of the Ilongot city-states was called a benganganat, while for the Gaddang it was called a mingal.[22][23][24]

The Ilocano people in northwestern Luzon were originally located in modern-day Ilocos Sur and were led by a babacnang. Their polity was called Samtoy which did not have a royal family but was headed as a chieftaincy.

The people of the Cordilleras, collectively known by the Spanish as Igorot, were headed by an apo. These civilizations were highland plutocracies with distinct cultures where most were headhunters. According to literature, some Igorot people were always at war with the lowland Ilocano people from the west.[25][26]

In Mindanao

The Lumad people from inland Mindanao are known to have been headed by a datu.

The Subanon people in the Zamboanga Peninsula were ruled by a timuay until they were overcame by the Sultanate of Sulu in the 13th century.

The Sama-Bajau people in Sulu who were not Muslims nor affiliated with the Sultanate of Sulu were ruled by a nakurah before the arrival of Islam.

Trade

Trade with China is believed to have begun during the Tang dynasty, but grew more extensive during the Song dynasty.[27] By the 2nd millennium CE, some Philippine polities were known to have sent trade delegations which participated in the Tributary system enforced by the Chinese imperial court, trading but without direct political or military control.[28][8] The items much prized in the islands included jars, which were a symbol of wealth throughout South Asia, and later metal, salt and tobacco. In exchange were traded feathers, rhino horns, hornbill beaks, beeswax, bird's-nests, resin, and rattan.

Indian influence

Indian cultural traits, such as linguistic terms and religious practices, began to spread within the Philippines during the 10th century, likely via the Hindu Majapahit empire.[11][7][29]

Writing systems

Brahmic scripts influenced the use of the Kawi script and the creation of several native writing systems.[30] The Laguna Copperplate Inscription was written using the Kawi script.

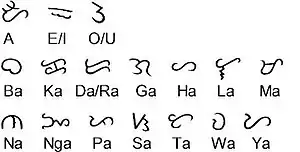

Baybayin script

By the 13th or 14th century, the Baybayin script used for the Tagalog language. It spread to Luzon, Mindoro, Palawan, Panay and Leyte, but there is no proof it was used in Mindanao.

There were at least three varieties of Baybayin in the late 16th century. These are comparable to different variations of Latin which use slightly different sets of letters and spelling systems.[31]

In 1521, the chronicler Antonio Pigafetta from the expedition of Ferdinand Magellan noted that the people that they met in Visayas were not literate. However, in the next few decades the Baybayin script seemed to have been introduced to them. In 1567 Miguel López de Legaspi reported that "they [the Visayans] have their letters and characters like those of the Malays, from whom they learned them; they write them on bamboo bark and palm leaves with a pointed tool, but never is any ancient writing found among them nor word of their origin and arrival in these islands, their customs and rites being preserved by traditions handed down from father to son without any other record."[32]

Earliest documented Chinese contact

The earliest date suggested for direct Chinese contact with the Philippines was 982. At the time, merchants from "Ma-i" (now thought to be either Bay, Laguna on the shores of Laguna de Bay,[33] or a site called "Mait" in Mindoro[34][35]) brought their wares to Guangzhou and Quanzhou. This was mentioned in the History of Song and Wenxian Tongkao by Ma Duanlin which were authored during the Yuan Dynasty.[34]

Arrival of Islam

Beginnings

Muslim traders introduced Islam to the then-Indianised Malayan empires around the time that wars over succession had ended in the Majapahit Empire in 1405. However, by 1380 Makhdum Karim had already brought Islam to the Philippine archipelago, establishing the Sheik Karimal Makdum Mosque in Simunul, Tawi-Tawi, the oldest mosque in the country. By the 15th century, Islam was established in the Sulu Archipelago and spread from there.[36] Subsequent visits by Arab, Malay and Javanese missionaries helped spread Islam further in the islands.

The Sultanate of Sulu once encompassed parts of modern-day Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. Its royal house claims descent from Muhammad.

Bruneian attacks

.png.webp)

Early in the 16th century, the Bruneian Empire under Sultan Bolkiah attacked the Kingdom of Tondo.[1][37]

Spanish expeditions

The following table shows some important details about the expeditions made by the Spanish to the Philippine archipelago.

| Year | Leader | Ships | Landing |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1521 | Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepcion, Santiago and Victoria | Homonhon, Limasawa, Cebu | |

| 1525 | Santa María de la Victoria, Espiritu Santo, Anunciada, San Gabriel, Jayson Ponce, Santa María del Parral, San Lesmes and Santiago | Surigao, Visayas, Mindanao | |

| 1527 | 3 unknown ships | Mindanao | |

| 1542 | Santiago, Jorge, San Antonio, San Cristóbal, San Martín, and San Juan | Samar, Leyte, Saranggani | |

| 1564 | San Pedro, San Pablo, San Juan and San Lucas | first landed on Samar, established colonies as part of Spanish Empire |

First expedition

Although the archipelago may have been visited before by the Portuguese (who conquered Malacca City in 1511 and reached Maluku Islands in 1512), the earliest European expedition to the Philippine archipelago was led by the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan in the service of King Charles I of Spain in 1521.[38]

The Magellan expedition sighted the mountains of Samar at dawn on the 17th March 1521, making landfall the following day at the small, uninhabited island of Homonhon at the mouth of the Leyte Gulf.[39] On Easter Sunday, 31 March 1521, in the island of Mazaua, Magellan planted a cross on the top of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed the islands he had encountered for the King of Spain, naming them Archipelago of Saint Lazarus as stated in "First Voyage Around The World" by his companion, the chronicler Antonio Pigafetta.[40]

Magellan sought alliances among the people in the islands beginning with Datu Zula of Sugbu (Cebu), and took special pride in converting them to Christianity. Magellan got involved in the political conflicts in the islands and took part in a battle against Lapulapu, chief of Mactan and an enemy of Datu Zula.

At dawn on 27 April 1521, Magellan with 60 armed men and 1,000 Visayan warriors had great difficulty landing on the rocky shore of Mactan where Lapulapu had an army of 1,500 waiting on land. Magellan waded ashore with his soldiers and attacked Lapulapu's forces, telling Datu Zula and his warriors to remain on the ships and watch. Magellan underestimated the army of Lapulapu, and, grossly outnumbered, Magellan and 14 of his soldiers were killed. The rest managed to reboard the ships.

The battle left the expedition with too few crewmen to man three ships, so they abandoned the "Concepción". The remaining ships – "Trinidad" and "Victoria" – sailed to the Spice Islands in present-day Indonesia. From there, the expedition split into two groups. The Trinidad, commanded by Gonzalo Gómez de Espinoza tried to sail eastward across the Pacific Ocean to the Isthmus of Panama. Disease and shipwreck disrupted Espinoza's voyage and most of the crew died. Survivors of the Trinidad returned to the Spice Islands, where the Portuguese imprisoned them. The Victoria continued sailing westward, commanded by Juan Sebastián Elcano, and managed to return to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain in 1522.

Subsequent expeditions

After Magellan's expedition, four more expeditions were made to the islands, led by García Jofre de Loaísa in 1525, Sebastian Cabot in 1526, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón in 1527, and Ruy López de Villalobos in 1542.[41]

In 1543, Villalobos named the islands of Leyte and Samar Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip II of Spain, at the time Prince of Asturias.[42]

Conquest of the islands

Philip II became King of Spain on January 16, 1556, when his father, Charles V, abdicated both the Spanish and HRE thrones. The latter went to his uncle, Ferdinand I. On his return to Spain in 1559, the king ordered an expedition to the Spice Islands, stating that its purpose was "to discover the islands of the west".[43] In reality its task was to conquer the Philippine islands.[44]

On November 19 or 20, 1564, a Spanish expedition of a mere 500 men led by Miguel López de Legazpi departed Barra de Navidad, New Spain, arriving at Cebu on February 13, 1565.[45] It was this expedition that established the first Spanish settlements. It also resulted in the discovery of the tornaviaje return route to Mexico across the Pacific by Andrés de Urdaneta,[46] heralding the Manila galleon trade, which lasted for two and a half centuries.

See also

- Antonio de Morga

- Anito

- Antonio Pigafetta

- Philippine shamans

- Barangay (pre-colonial)

- Baybayin

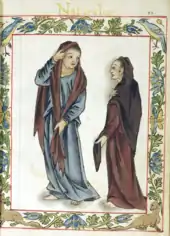

- Boxer Codex

- Cainta (historical polity)

- Huangdom of Pangasinan

- Dambana

- Datu

- Enrique of Malacca

- Ferdinand Magellan

- First Mass in the Philippines

- Kingdom of Tondo

- Lakan

- Lacandola Documents

- Lapulapu

- List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

- Luções

- Ma-i

- Madja-as

- Maginoo

- Maharlika

- Pintados

- Rajah Humabon

- Rajahnate of Butuan

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Sultanates in Lanao

- Rajahnate of Maynila

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Suyat

- Timawa

- Warfare in pre-colonial Philippines

- Thimuay

- Subanon people

- Rajah

- Tawalisi

- History of the Philippines

- Prehistory of the Philippines

- History of the Philippines (Spanish Era 1521–1898)

- History of the Philippines (American Era 1898–1946)

- History of the Philippines (Third Republic 1946–65)

- History of the Philippines (Marcos Era 1965–86)

- History of the Philippines (Contemporary Era 1986–present)

Notes

References

-

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- "Philippines | The Ancient Web". theancientweb.com. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Scott, William Henry (1992), Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino. New Day Publishers, Quezon City. 172pp. ISBN 9711005247.

- Patricia Herbert; Anthony Crothers Milner (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and Literatures : a Select Guide. University of Hawaii Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8248-1267-6.

- Postma, Antoon (1992). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 182–203.

- Newson, Linda A. (April 16, 2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8248-6197-1.

- Jocano, F. Landa (2001). Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage. Quezon City: Punlad Research House, Inc. ISBN 978-971-622-006-3.

- Junker, Laura Lee (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8248-2035-0. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Miksic, John N. (2009). Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 978-981-4260-13-8.

- Sals, Florent Joseph (2005). The history of Agoo : 1578–2005. La Union: Limbagan Printhouse. p. 80.

- Jocano, Felipe Jr. (August 7, 2012). Wiley, Mark (ed.). A Question of Origins. Arnis: Reflections on the History and Development of Filipino Martial Arts. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0742-7.

- "Timeline of history". Archived from the original on November 23, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- Ring, Trudy; Robert M. Salkin & Sharon La Boda (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. pp. 565–569. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- Historical Atlas of the Republic. The Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. 2016. p. 64. ISBN 978-971-95551-6-2.

- Legarda, Benito Jr. (2001). "Cultural Landmarks and their Interactions with Economic Factors in the Second Millennium in the Philippines". Kinaadman (Wisdom) A Journal of the Southern Philippines. 23: 40.

- Carley, Michael (November 4, 2013) [2001]. "7". Urban Development and Civil Society: The Role of Communities in Sustainable Cities. Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 9781134200504. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Each boat carried a large family group, and the master of the boat retained power as leader, or datu, of the village established by his family. This form of village social organization can be found as early as the 13th century in Panay, Bohol, Cebu, Samar and Leyte in the Visayas, and in Batangas, Pampanga and Tondo in Luzon. Evidence suggests a considerable degree of independence as small city-states with their heads known as datu, rajah or sultan.

- Tan, Samuel K. (2008). A History of the Philippines. UP Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-971-542-568-1. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Mallari, Perry Gil S. (April 5, 2014). "War and peace in precolonial Philippines". Manila Times. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Newson, Linda (2009) [2009]. "2". Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press. p. 18. doi:10.21313/hawaii/9780824832728.001.0001. ISBN 9780824832728. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Given the significance of the size and distribution of the population to the spread of diseases and their ability to become endemic, it is worth commenting briefly on the physical and human geography of the Philippines. The hot and humid tropical climate would have generally favored the propagation of many diseases, especially water-borne infections, though there might be regional or seasonal variations in climate that might affect the incidence of some diseases. In general, however, the fact that the Philippines comprise some seven thousand islands, some of which are uninhabited even today, would have discouraged the spread of infections, as would the low population density.

- Scott, William Henry (1992). Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino.. p. 2.

- Woods, Damon L. (1992). "Tomas Pinpin and the Literate Indio: Tagalog Writing in the Early Spanish Philippines" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Islands of Leyte and Samar – National Commission for Culture and the Arts".

- "ILONGOT – National Commission for Culture and the Arts".

- "GLIMPSES: Peoples of the Philippines".

- "Politico-Diplomatic History of the Philippines – National Commission for Culture and the Arts".

- "Biag ni Lam-ang: Summary / Buod ng Biag ni Lam-ang". August 28, 2017.

- Glover, Ian; Bellwood, Peter; Bellwood, Peter S.; Glover, Dr (2004). Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. Psychology Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-415-29777-6. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Scott 1994.

- Osborne, Milton (2004). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History (Ninth ed.). Australia: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-448-2.

- Baybayin, the Ancient Philippine script Archived August 8, 2010, at WebCite. Accessed September 4, 2008.

- Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin Styles & Their Sources". Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- de San Agustin, Caspar (1646). Conquista de las Islas Filipinas 1565-1615.

'Tienen sus letras y caracteres como los malayos, de quien los aprendieron; con ellos escriben con unos punzones en cortezas de caña y hojas de palmas, pero nunca se les halló escritura antinua alguna ni luz de su orgen y venida a estas islas, conservando sus costumbres y ritos por tradición de padres a hijos din otra noticia alguna.'

- Go, Bon Juan (2005). "Ma'l in Chinese Records – Mindoro or Bai? An Examination of a Historical Puzzle". Philippine Studies. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University. 53 (1): 119–138. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- Patanne, E. P. (1996). The Philippines in the 6th to 16th Centuries. San Juan: LSA Press. ISBN 971-91666-0-6.

- Scott, William Henry. (1984). "Societies in Prehispanic Philippines". Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 971-10-0226-4.

- McAmis, Robert Day. (2002). Malay Muslims: The History and Challenge of Resurgent Islam in Southeast Asia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 18–24, 53–61. ISBN 0-8028-4945-8. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- del Mundo, Clodualdo (September 20, 1999). "Ako'y Si Ragam (I am Ragam)". Diwang Kayumanggi. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Zaide, Gregorio F.; Sonia M. Zaide (2004). Philippine History and Government (6th ed.). All-Nations Publishing Company. pp. 52–55. ISBN 971-642-222-9.

- Zaide 2006, p. 78

- Zaide 2006, pp. 80–81

- Zaide 2006, pp. 86–87.

- Scott 1985, p. 51.

- Williams 2009, p. 14

- Williams 2009, pp. 13–33.

- M.c. Halili (2004). Philippine History' 2004 Ed.-halili. Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- Zaide 1939, p. 113

Further reading

- Scott, William Henry. (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History (Revised Edition). New Day Publishers, Quezon City. ISBN 9711002264.

.svg.png.webp)