Jose Diokno

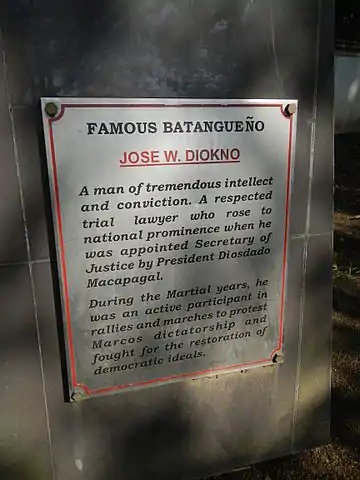

Jose Wright Diokno GCrL (February 26, 1922 – February 27, 1987), also known as "Ka Pepe", was a Filipino nationalist, lawyer, and statesman. Regarded as the "Father of Human Rights Advocacy in the Philippines",[2] he served as Senator of the Philippines, Secretary of Justice, founding chair of the Commission on Human Rights, and founder of the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG), the premier group of Filipino human rights lawyers. Diokno is the only person to top both the Philippine Bar Examination and the board exam for Certified Public Accountants (CPA). His career was dedicated to the promotion of human rights, the defense of Philippine sovereignty, and the enactment of pro-Filipino economic legislation.

Jose W. Diokno | |

|---|---|

| Senator of the Philippines | |

| In office December 30, 1963 – September 23, 1972[1] | |

| Secretary of Justice | |

| In office December 31, 1961 – May 19, 1962 | |

| President | Diosdado Macapagal |

| Preceded by | Alejo Mabanag |

| Succeeded by | Juan Liwag |

| Chairman of the Presidential Committee on Human Rights | |

| In office 1986–1987 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 26, 1922 Manila, Philippine Islands |

| Died | February 27, 1987 (aged 65) Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines |

| Nationality | Filipino |

| Political party | Nacionalista Party (1963-1971) |

| Spouse(s) | Carmen Reyes "Nena" Icasiano-Diokno |

| Relations | Jose Manuel "Chel" Diokno (son) Maria Serena "Maris" Diokno (daughter) Jose Lorenzo "Pepe" Diokno (grandson) |

| Alma mater | De La Salle University University of Santo Tomas |

| Occupation | Public official, Lawyer, Accountant, Activist |

| Website | diokno |

In 2004, Diokno was posthumously conferred the Order of Lakandula with the rank of Supremo—the Philippines' highest honor.[3] February 27, a day after his birthday, is celebrated in the country as Jose W. Diokno Day.[4]

Early life and education

Jose W. Diokno was born in Manila on Feb. 26, 1922, to Ramón Diokno y Marasigan, a former senator and Justice of the Supreme Court, and Leonor Wright, an American mestiza of British descent.

Diokno had nine siblings, and some half-siblings from Ramón's first spouse, Martha Fello Diokno, who passed away years ago. Diokno had some Irish, Spanish, Chinese, Mexican or Native American, and very scant South Asian descent. He would later often say that he was "100% Filipino".[5] Ramón Diokno was considered an anti-imperialist nationalist as senator. He opposed the American Parity Rights Amendment and was one of four to be ousted so that the amendment may be ratified. Jose W. Diokno's grandfather was Ananías Diokno, a general in the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War who represented the revolutionary forces in Visayas.[6] Ananías's great-great grandfather was Félix Berenguer de Marquina, the viceroy of New Spain and governor-general of the Philippines from 1788 to 1793, who had an extramarital affair with a Filipina mestiza named Demetria Sumulong and sired a daughter. He abandoned his family to return to Spain in 1795 and later became lieutenant-general of the navy in 1799. He was said to be incompetent as governor but persevering.[7]

As a young 12 year old boy, Diokno would go with his father to trials in the provinces. He would carry his father’s bag, and sit on a small chair reserved for him behind the counsel’s table. He initially wanted to pursue a career in other fields such as commerce, but eventually was influenced to take up law once he came of age. He learned English through a private tutor during the American Commonwealth period. Growing up, Diokno relished having Spanish dishes at home, namely tapas or side dishes such as angulas, white embutido, galantina, and chorizos. He liked Filipino food as well and enjoyed rice mixed with gatas ng kalabaw (carabao’s milk), raw eggs, and tapang usa (cured venison).[8]

In 1937, Diokno graduated as valedictorian of his high school class at De La Salle College, Manila, now called De La Salle University (DLSU), and went on to take a bachelor's degree in commerce, also at DLSU. He graduated from college summa cum laude at age 17 due to repeated acceleration.[9][10] Diokno took the CPA board examinations in 1940—for which he had to secure special dispensation, since he was too young at 18 and only in his second year of law school at the University of Santo Tomas (UST). He topped the CPA with a grade of 81.18.[5] Unfortunately, since Diokno was too young when he passed the CPA exam, he could not earn a proper license until he was around 21 years old, which contributed to his decision to follow his father's wishes and attend law school like his other siblings.[11]

After Diokno enrolled in law at UST, his studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. During the war, Diokno continued his education by reading his father's law books. He would sometimes ask his father, who was known to be stern and enforced speaking only Spanish or generally no English at home, to test his abilities. His father would reply, "You either know it or you don't. Just read."[12] When the war was over, he was granted a special dispensation by the Supreme Court of the Philippines and was allowed to take the Philippine Bar Examination despite having never completed a law degree. He topped the 1944 bar exam together with a 24 year old future ally named Jovito Salonga with a score of 95.3, the highest since Jose L. Quintos of Bulacan set the record in 1903.[5] As a reward he took a solo vacation in the United States, where he would frequently call Carmen "Nena" Icasiano, a commerce student from Bulacan studying at Far Eastern University. They met in 1946 at a dinner party hosted by a future politician named Arsenio Lacson, and eventually got married in a Manila church immediately after Diokno returned from his shortened trip. He quickly proposed to her after he found out on the telephone that she was sick and had missed seeing him.[13]

Rising lawyer and Secretary of Justice years

Immediately after topping the Bar exam, Diokno embarked on his law practice at his father's bupete or law office, handling and winning high-profile cases including an election case on behalf of his ill father, Sen. Ramón Diokno, who let the young Diokno quickly take over the bupete. Diokno also successfully fought libel charges against radio personality and Manila Mayor Arsenio Lacson, who was a close friend and would often visit Diokno and his wife in the wee hours at their home in Parañaque to prepare them breakfast. Diokno would in turn edit Mayor Lacson's newspaper columns. Historians learned a few years after Mayor Lacson's sudden passing that Lacson even intended for Diokno to be his running mate, as the Manila Mayor's fame made him the top presidential candidate for the 1965 election.[14] By 1958, Diokno gained enough stature to be selected to join a special committee to investigate the Department of Finance. He was later invited to return to investigate anomalies happening in the Bureau of Supply Corrections.[15]

With his reputation as a legal practitioner established and secured, in 1961, Diokno was appointed Secretary of Justice by President Diosdado Macapagal through Lacson's support.

In March 1962, Diokno ordered a raid on a firm owned by Harry S. Stonehill, an American businessman who was suspected of tax evasion and bribing public officials, among other crimes. Diokno's investigation of Stonehill further revealed corruption within government ranks, and as Secretary of Justice, he prepared to prosecute those involved. However, President Macapagal intervened, negotiating a deal that absolved Stonehill in exchange for his deportation, then ordering Diokno to resign. Diokno only learned of his resignation from the news and received death threats from supporters of the president, which prompted Mayor Lacson to offer Diokno special security. Diokno questioned Macapagal's actions, saying, "How can the government now prosecute the corrupted when it has allowed the corrupter to go?" Macapagal would become unpopular and eventually lose the next election in 1965 to another controversial politician also connected with Stonehill named Ferdinand Marcos.[16][17]

Senator

Months later in 1963, Diokno ran for senator under the Nacionalista Party in the 1963 elections, and won with almost half of the popular vote.

His laws and bills were often considered nationalistic in essence, as he called for the creation of the Equal Pay for Equal Work Act, which would ban discrimination of Filipinos in American companies. The infamous ex-president of San Miguel Corp. named Andy Soriano, who manipulated the Philippine Association, and US Ambassador Bill Blair controversially fought to have the bill eventually vetoed before they stepped down from their positions.[18] Diokno often fought American policies that involved transfer pricing.

For his performance as legislator and fight for nationalism, Diokno was named Outstanding Senator by the Philippines Free Press from 1967 to 1970, making him the only legislator to receive the recognition for four successive years. Diokno also served as the delegate for many commissions including the United Nations General Assembly in the middle of the 1960s.[15]

Chairmanship of the Economic Affairs Committee

_-_BOI.svg.png.webp)

Senator Diokno became chairman of the Senate Economic Affairs Committee, and worked for the passage of pro-Filipino legislation, including what is considered to be the most important incentive law in the country, RA 5186, also known as the Investment Incentives Act of 1967, which provides incentives to mostly Filipino investors and entrepreneurs that would place control of the Philippine economy predominantly in the hands of Filipinos.[19] The law would also be the first groundbreaking initiative of the Philippine economy to gradually step out of its import substitution mindset.[20] It also led to the foundation of the Board of Investments, the premier government agency responsible for propagating investments in the Philippines.

Diokno then authored RA 6173 or the Oil Industry Commission Act of 1971, which created the Oil Industry Commission (OIC) to regulate oil pricing in different companies. This eventually led to the dominance of three oil companies in Caltex, the alternative name of the American corporation Chevron, Petron, a local partner of Middle-Eastern Saudi Aramco and is owned by the monopoly brewery San Miguel Corporation, and Shell based in the Netherlands.[18] He also authored Joint Resolution No. 2, which set the policies for economic development and social progress. In addition to that, he sponsored and co-authored the Export Incentives Act of 1970 and the Revised Election Law, among many others.

Civil rights activism

In 1971, Diokno sensed a shift in the Marcos presidency toward authoritarianism. Diokno and Marcos were members of the Nacionalista Party, but Diokno was a lifelong member because of his father while Marcos left the Liberal Party to create an opportunity to run against party-mate Macapagal for the presidency.[21] When Marcos suspended the fundamental legal right of the writ of habeas corpus following the president's bombing of the Plaza Miranda gathering of Liberal Party members, Diokno resigned from the Nacionalista Party in protest and took to the streets.[22] Sen. Diokno called on students to start protesting against the administration, anticipating that Marcos, who was nearing the end of his last term, would declare martial law and change the constitution to give himself absolute power.[5][23]

Previously, Marcos began building notoriety following the Jabidah massacre, where an estimated 14 to as much as 68 alleged Muslim youths were gunned down in Corregidor by unknown armed men in 1968.[24] Following this event, a Moro insurgency would quickly develop, starting in Mindanao; it would evolve into a widespread armed-conflict that would engulf the nation decades after Marcos's lifetime.[25] Marcos tried to suppress the media and block coverage of the event, but it was too late. Diokno and many other senators sensed Marcos might have developed a hidden agenda.[26] From then on, Diokno began to put greater emphasis on human rights in public speeches and events. In an oft-quoted 1981 speech, he would declare, "No cause is more worthy than the cause of human rights. Human rights are more than legal concepts: they are the essence of man. They are what make man human. That is why they are called human rights: deny them and you deny man's humanity."[27]

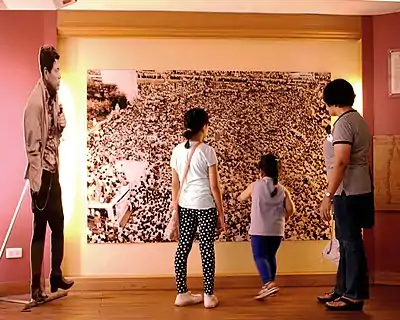

He was the leader of the Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties (MCCCL), which organized a series of rallies from 1971 to 1972.[28] The most massive of these rallies involved 50,000 protestors and was held on 21 September 1972, shortly before the imposition of martial law by the Marcos dictatorship.[28] During this rally, protestors denounced the infamous Oplan Sagittarius, the devious operation plan by Marcos to declare martial law. Sen. Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino exposed the Oplan Sagittarius scandal earlier in a September 13 speech, and spoke to the Senate on September 21, the same day that the MCCCL held their exceptionally large rally at Plaza Miranda. Marcos reacted with fear of deposition and immediately finalized Proclamation No. 1081, which declared nationwide martial law at 8:00 p.m. later that evening. Exactly the next day on September 22, 1972 at 8:00 p.m., Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile was told to exit his car near Wack-Wack village.[29] Another vehicle carrying gunmen arrived and stopped near an electrical post, right beside Enrile's vehicle. They then alighted from their vehicle and began to fire at the large sedan of Enrile to give an impression of a terrorist ambush, setting the stage for Marcos's theatrical television announcement.[30][31][32]

Martial law years

Imprisonment and organized coalitions

On September 23, 1972, Diokno's second term as senator was officially cut short when Marcos announced martial law on television at 7:17 p.m.

At 1:00 a.m. before the announcement, Diokno was arrested by the dictatorship. After cutting communication lines in multiple neighborhoods, including Diokno's home, six carloads carrying forty armed soldiers visited Diokno at his home to "invite" him for questioning. He changed from his pajamas and was sent to Camp Crame. They had no warrant.[5]

After Diokno was brought to Camp Crame, he was transferred to Fort Bonifacio, where he was detained along with other opposition members such as Aquino and Chino Roces, the founder and head of The Manila Times, the leading newspaper at the time. The military's Defense Minister Enrile offered a security detail to Diokno "to protect (him) from Communist assassins", to which Diokno laughed and responded that he really needed protection from the military.[33]

Diokno and Aquino, whom the dictatorship considered their foremost opponents, were later handcuffed, blindfolded, and transferred via a chopper to solitary confinement at Fort Magsaysay, located in the municipality of Laur, Nueva Ecija. They remained confined to Fort Magsaysay for exactly thirty days. They both learned of each other's presence through singing. One of them would frequently sing the national anthem Lupang Hinirang or "Chosen Land", to which the other would reply by singing Bayan Ko or "My Country" to prove he was still alive.[34] To tally the number of days, Diokno used knots of ropes from his mosquito net as well as the back of a soap packaging box and crossed out each day in the manner of a calendar. His visiting family members were often strip-searched by soldiers. They would sneak in books in French and Spanish for him to read, and he would converse to his wife in Spanish for only them to comprehend. Diokno would tell his family not to weep in front of the sadistic soldiers. Only his Aunt Paz Wilson, a woman in her 90s and a mother figure since his mother's passing, would frequently cry during every visit. She continued to visit despite also undergoing strip searches. The family would be in tears once they left the prison, where the Aquino family would see them. This helped the Aquinos prepare themselves emotionally since they never saw the Diokno family manifest much pain before. Nena Diokno, suspicious of Marcos, took most of her husband's books at the library along M.H. del Pilar and brought them home before the military burned down the library. Jose would thank her as he was very familiar with the library and memorized the location of each shelf and book he read.[35] Outside the prison, Marcos announced at his executive mansion, Malacañang Palace that September 21 would be known as "National Thanksgiving Day", the same day Diokno led his biggest Plaza Miranda rally. This declaration has led to a general confusion about the true date of the public announcement of martial law, which was actually on September 23, two days after Proclamation No. 1081 was signed. Diokno spent 718 days, or nearly two years in detention, mainly at the maximum security compound of Fort Bonifacio. While Aquino was charged with subversion, no charge was ever filed against Diokno. Diokno was released arbitrarily on September 11, 1974—Marcos's 57th birthday. After his release, Sen. Diokno served as an instructor and taught some law courses at the University of the Philippines (UP) at the request of the university and its students after he was released from Fort Bonifacio. This continued until Marcos found out and had him banned, though Diokno continued returning for speeches and conferences, and was later honored with a mural of him and other martial law heroes at the school's main college of Palma Hall.

A year later, in 1975, Diokno was chosen as chairman of the Civil Liberties Union, a position he held until 1982. Later in March 1983, Diokno founded the Kilusan sa Kapangyarihan at Karapatan ng Bayan (Movement for People's Sovereignty and Democracy) Organization or KAAKBAY, which was ideologically independent of beliefs like Marxism but was joined by fellow Marxists and Capitalists. KAAKBAY influenced the public and fought hard against the Marcos administration using non-violent activism or "pressure politics". KAAKBAY later elevated pressure politics as an important principle for post-democracy through its publication called "The Plaridel Papers".[36] The August 1984 edition of The Plaridel Papers popularized the concept of pressure politics and introduced a political system that would involve the "parliament-of-the-streets" in building a "popular democracy".[37] KAAKBAY was also one of the main member organizations of the Justice for Aquino, Justice for All (JAJA) coalition, which was founded by Diokno on August 25, 1983 following Ninoy Aquino's assassination for returning to the country to face Marcos. JAJA was the first united front against Marcos, but it did not last long. KAAKBAY served as the main coalition that kept the other extreme groups from leaving JAJA. Unfortunately, JAJA was later replaced by the predominantly leftist Coalition of Organizations for the Restoration of Democracy (CORD) in mid-1984, which had almost the same members. Before the creation of CORD, many former JAJA members who disagreed with the communists also organized a much wider alliance called the Kongreso ng Mamamayang Pilipino (KOMPIL) or the Congress of the Filipino People, and was mainly headed by Diokno.[38]

From January 7 to January 8, 1984, 2,300 delegates representing all sectors gathered at the KOMPIL congress to vote on multiple issues. One of the decisions voted by 60% of the attendees was to establish a new Commission on Elections (COMELEC). Elected leaders included statesmen such as Diokno, Lorenzo Tañada, Aquilino Pimentel, Cecilia Muñoz-Palma, Ambrosio Padilla, Salvador Laurel, and Jovito Salonga. Others came from non-political sectors, including Makati's Enrique Zobel, who was related to Andy Soriano and due to consanguinity was part of the Ayala Corporation. Another leader was Jaime Cardinal Sin, who would play an important role two years later for the opposition. Of all the issues, the largest was concerning a letter they made called the Call for Meaningful Elections (CAMEL). Some including Diokno and Aquino's brother Butz preferred to boycott any election to avoid legitimizing the Marcos rule. On the other hand, some of the other signatories preferred to participate in the elections, including Ninoy Aquino's widow, Corazon Cojuangco-Aquino.[39]

Diokno was a part of multiple organizations and alliances that fought the administration and foreign intervention. He continued to attack the different policies of the Marcos administration, such as their controversial nuclear programs that led to the sabotaged construction of the costly Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, thereby infuriating Marcos.[40] Diokno continued to serve as the leader behind ceasing Marcos's numerous incomplete projects.

Human rights work

Immediately after his release, Diokno set up the Free Legal Assistance Group or FLAG in 1974, which gave free legal services to the victims of martial law. It was the first and largest association of human rights attorneys ever assembled in the nation. In court, Diokno personally defended tribal groups, peasants, social workers threatened by exploitation, and military atrocities, which he represented pro-bono. FLAG popularized developmental legal aid and even doled out allowances to its clients. This has led to new laws requiring newly sworn-in lawyers to provide free legal assistance for a certain amount of time.[41] FLAG handled 90 percent of human rights cases in the country.[15] Diokno was also involved in documenting cases of torture, summary execution, and disappearances under the Marcos regime.[5]

Diokno had no fear of being arrested again, and went around and outside the Philippines, spreading a message of hope and democracy. In another oft-quoted speech, he once quipped:

And so law in the land died. I grieve for it but I do not despair over it. I know, with a certainty no argument can turn, no wind can shake, that from its dust will rise a new and better law: more just, more human, and more humane. When that will happen, I know not. That it will happen, I know.[27]

Diokno also held an important role in Southeast Asia leading a group of senior human rights lawyers from Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines in forming the Regional Council on Human Rights in Asia. The group was one of the first non-governmental organizations (NGOs) built to promote human rights in Southeast Asia. On December 9, 1983 in Manila, the Regional Council formalized the first human rights declaration of Southeast Asia called the Declaration of the Basic Duties of ASEAN Peoples and Governments.[42][43] Although the council paved the way for future human rights declarations by other organizations like the United Nations, their momentum gradually declined decades after the Marcos regime ended.[44] Diokno was also, inter alia, the chairman of the first Human Rights Information and Documentation Systems, International (HURIDOCS) assembly in Strasbourg, France, which was a historic event that involved over two hundred representatives.[45][46][47] HURIDOCS founder Hans Thoolen said years later in a tribute to Diokno that he witnessed Diokno present novel ideas on practical ways to defend human rights victims at the 1983 SOS-Torture constituent assembly held in Geneva, Switzerland, and that Diokno frequently disseminated human rights primers published in the common vernacular for mass audiences.[48][49]

Later years and legacy

People Power and final years

After founding JAJA together with friend and former Sen. Lorenzo M. Tañada, Diokno was chosen to serve as chairman of its executive committee. The two leaders were the only members to call for a boycott in the upcoming, nationwide Batasan Elections, predicting that it would be fixed.[50]

Eventually public outcries after the election results came out with Marcos winning led to the 1986 People Power Revolution that peacefully ousted the Marcos family out of the country. Diokno was appointed by the new President Corazon Cojuangco-Aquino or Cory, wife of the slain Ninoy Aquino and mother of the future 15th president, Benigno "Noynoy" Aquino, to serve as founding chairman of the Presidential Committee on Human Rights, now the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), and tasked to lead a government panel to negotiate for the return of rebel forces to the government folds. Diokno helped write the 1987 Constitution, particularly Article XIII defining social justice and human rights.[51] Diokno was also the principal negotiator in peace talks with the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, the main leftist coalition founded during martial law.[15]

Diokno would be disappointed, however, by the Mendiola massacre on January 22, 1987, when 51 farmers staging a peaceful rally in Mendiola were gunned down by the military under Aquino. Diokno resigned from his two government posts in deep disgust and great sadness. His daughter Maris noted that "it was the only time we saw him near tears."[5]

In May 1984, even before People Power and its preceding, rigged Batasan Elections, Diokno had been diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. He obtained a high fever and was brought to the Stanford University Medical Center where he learned of his disease. He had smoked all his adult life. Diokno visited the San Francisco University Hospital to have a brain scan and found a brain tumor. He would return to the motherland and on July 4, 1986, which was the U.S. independence day, had a series of debates with Minister Enrile, convincing him that U.S. bases should be removed from the country. Enrile, who betrayed Marcos and joined the new administration, was inspired by this debate and would later become senator and lead the vote to oust the American military from the country. Diokno returned to the United States on September 3, 1986 for treatment. Eventually after having a transfusion a month later at Manila Doctors Hospital, Diokno decided to stop all treatments and return to his home in Quezon City, to spend his final days reading and writing cases after he shaved his hair off and had experienced a declining line of vision. He continued to work all out for four more months, despite his illness, until his passing on Feb. 27, 1987 at 2:40 a.m.—one day after his 65th birthday. Diokno had spent the last decade of his life making documentaries and speeches, and leading different coalitions and rallies on the streets. His funeral was held at the National Shrine of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in Quezon City.[18][52]

Honors, awards, and historical reputation

Following Diokno's passing, President Cory Aquino declared March 2–12, 1987 as a period of national mourning, with flags flown at half-staff. Expressing her grief, Aquino said, "Pepe braved the Marcos dictatorship with a dignified and eloquent courage our country will long remember."[53] She quoted what her husband Ninoy would often tell his friends that Diokno was "the one man he would unquestioningly follow to the ends of the earth", and that he was "the most brilliant Filipino". As part of KAAKBAY's group of intellectuals, UP Professor Randy David admired Diokno and called him the "best president we did not have", while London's Amnesty International called him the "champion of justice and human rights in Asia". Diokno became famous in the United Kingdom after creating a martial law documentary called "To Sing Our Own Song" with the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1982.[54] Out of frustration, Marcos subpoenaed Diokno and interviewee Cardinal Sin to testify before the Supreme Court regarding their roles in the documentary and connection with another involved human rights hero named Horacio Morales, who used the documentary as trial evidence against the military. Marcos even threatened the British embassy and gave them an order to cancel the documentary, which the British decidedly ignored.[55] Diokno was later honored in 2005 as the De La Salle Distinguished Lasallian Awardee by the De La Salle Alumni Association (DLSAA), of which he was once a member of.[15]

Diokno's nationalist legacy made further headlines when on February 12, 1983, former Supreme Court Justice J.B.L. Reyes, UP President Salvador P. Lopez, and former senators Tañada and Diokno formed the Anti-Bases Coalition (ABC), with Diokno voted as the secretary general or the chairman of the coalition.[56] The influence of the ABC eventually led to the end of American military presence in the Philippines, notably in Subic Bay and Clark, Pampanga. The historic turnover ceremony transpired on November 24, 1992 under then-Philippine President Fidel Ramos.

In 2004, Diokno was posthumously conferred the Order of Lakandula with the rank of Supremo—the Philippines' highest honor, which was signed by former Pres. Diosdado Macapagal's daughter, the 14th president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. He was the first recipient of this honor.[57][3] By virtue of Proclamation No. 78, which was signed in 1987 by Pres. Cory Aquino and Executive Secretary and FLAG lawyer Joker Arroyo, February 27 is perennially celebrated in the country as Jose W. Diokno Day.[4][58]

In 2005, the De La Salle Professional Schools, Inc. Graduate School of Business (DLS-PSI-GSB) handed out the inaugural "Ka Pepe Diokno Award" as a champion of human rights. This was established along with another milestone, the establishment of the Jose W. Diokno Distinguished Professorial Chair in Business Law and Human Rights.[59] The first ever Ka Pepe Diokno award as a Champion of Human Rights was given to Voltaire Y. Rosales, Executive Judge of Tanauan, Batangas for his effort in protecting the downtrodden, even giving up his life for the cause. Subsequent annual awards have been given to worthy candidates such as Maria Ressa and Bishop Pablo Virgilio "Ambo " David, who in life or death, fulfilled the values of protecting human rights just as Senator Diokno did.[60]

In 2007, by virtue of Republic Act No. 9468, Bay Boulevard, a 4.38 kilometer road along the Bay City coastline, or Pasay and Parañaque City was renamed J.W. Diokno Boulevard in his honor and memory.

In 2017, the CHR erected a nine foot statue of Diokno at the center of the CHR compound entrance in Diliman, Quezon City, and the surrounding park was named Liwasang Diokno or the Diokno Freedom Park. The hall inside the compound is called Bulwagang Diokno or the Diokno Hall and features a bust and an accompanying mural of the late chairman.

Personal life and descendants

Sen. Diokno was married to Carmen Reyes "Nena" Icasiano-Diokno, with whom he had ten (10) children: Carmen Leonor or Mench, who was college valedictorian and joined the garment industry with husband Emil Ecsay; Jose Ramon or Popoy, who joined the Lopez family that established the ABS-CBN media corporation; Maria de la Paz or Pat, who joined a banking company called ComBank; Maria Serena or Maris, who is a nationally recognized historian; Maria Teresa or Maitep, who is a UP cum laude graduate of Economics and was executive director of a non-profit institution called IBON Foundation; Maria Socorro or Cookie, who worked for the Regional Council of Human Rights in Asia and assisted her father at FLAG; Jose Miguel or Mike, who is a US-based lawyer; Jose Manuel or Chel, who is a professor and lawyer; Maria Victoria or Maya, who was her father's secretary at CHR; and Martin Jose, who is a professional architect from UST and was adopted by the Diokno family in 1967 when he was just two weeks old.[61] His children all excelled in their studies, but Diokno would often chide his children about their lack of perfect scores, to which Maris would reply that studying in schools like the colonial, American-founded UP (which is the official public national university and where Sen. Diokno wished to enroll in but was banned by his politically-moderate parents) made very good scores the equivalent to perfect scores at DLSU, a private, sectarian Catholic university.[62] According to Chel, one of the traits that Diokno picked up at DLSU from the teaching brothers was to carry a rosary in his pocket. He would request it from guards while detained at Fort Bonifacio and Fort Magsaysay during martial law.[52]

Maris Diokno, a renowned historian, is the former chair of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, and former Vice President for Academic Affairs at UP. She studied at the University of London and graduated UP magna cum laude. She once resigned from the government during her first tenure after the Mendiola massacre.

Chel Diokno is a human rights lawyer, Chairman of FLAG, head of the Diokno Law Center and member of the Jose W. Diokno Foundation, founding Dean of the De La Salle University College of Law, and former Special Counsel of the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee. In 2019, Chel Diokno ran for Senator under the Liberal Party and nearly secured enough votes to obtain a seat. He joined forces with candidates of other parties to form the "Otso Diretso" (Direct Eight Candidates to the Senate) coalition, which opposed the Rodrigo Duterte administration. The administration of Duterte has been compared to the Marcos family rule without the privileged background or American ties of Marcos, but instead it has been seen currying favor with the dictatorship in Russia and the Communist Party of Mainland China.[63][64] Duterte has also committed human rights violations and like Marcos shut down the media corporation of ABS-CBN. FLAG has represented Rappler founder Maria Ressa, the Time Person of the Year in 2018 during court hearings filed against her by the Duterte administration for Rappler's reports on Duterte's War on Drugs and Murder of Drug Addicts.[65][66]

Sen. Diokno's grandson and Chel's firstborn child, Jose Lorenzo "Pepe" Diokno is the executive director of alternative education group Rock Ed Philippines.[67] He is best known as a motion picture director, producer, and screenwriter whose debut film, "Engkwentro" won the Venice Film Festival’s Lion of the Future Award in 2009, as well as Venice’s Orizzonti Prize, the NETPAC Award for Best Asian Film, and the Gawad Urian for Best Editing. Pepe used commercials and short films to market his father Chel during the 2019 election campaign period.[68][69]

Public image

Diokno is generally seen as the intellectual leader contrasted to the fierceness of Ninoy Aquino in opposing the perversion of the Marcos Administration.[70][71] According to National Artist F. Sionil José, Diokno almost always won his court battles from his mere presence alone that intimidated all judges. José asserted that Diokno could have convinced protestors to march to the gates of Malacañang, but he was never ambitious for power and always traveled free of any entourage of bodyguards. Around the time of Marcos, Diokno even lost his financial assets including his home in Magallanes, Makati before moving to Quezon City. Despite his difficulties, he still advocated and popularized his innovative new concept of developmental or free legal aid. This passion in José's eyes, made Diokno the true spirit of democracy and "stronger than Ninoy Aquino because he never aspired to take over from Marcos. And also because he stayed home" (This was since Aquino left for the United States after his release from prison).[72] He managed to have the ability to lead rival political factions together. As senator, Diokno had a strong relationship with technocrats such as Cesar E.A. Virata, Placido Mapa Jr., and Vicente Paterno, all of whom joined Marcos's administration during martial law. According to these economists and technocrats, Diokno did not carry preconceived notions of others provided that nationalist goals could be met. His willingness to work with people of contrasting ideologies allowed him to adopt the Investment Incentives Act of 1967.[73] Diokno was also popular among all social classes and became a liaison between Pres. Aquino's new government and the communists, whom he led in different coalitions in the past.[74] Despite Diokno's seemingly stoic demeanor and very simple lifestyle, Diokno was also known to be quite eloquent and was completely blunt with his opinions, as he usually avoided any sugarcoating. One instance was when he addressed an affluent American audience at the Westchester Country Club in New York:

"Let us do it as we believe it must be done, not as you would do it in our place. Let us make our mistakes, not suffer yours… With your help or despite your hindrance, Philippine nationalism will do the job. No one else can."

The audience fell completely silent after his address.[75]

Diokno also possessed a certain wry sense of humor, which made him appealing to others. He once was quoted saying, "You know me-Diokno, no joke." He tended to only laugh at others' humorous remarks rather than his own.[76] He was also well-respected by his peers, and he carried the same stature as other talented and brilliant scholar-activists in history, spanning from Jose Rizal and Apolinario Mabini to Claro M. Recto.[77]

Publications

Among his works are Diokno on Trial: Techniques and Ideals of the Filipino Lawyer - the Complete Guide to Handling a Case in Court, which was compiled and posthumously published by the Diokno Law Center in 2007. A Nation for Our Children, a collection of Jose W. Diokno’s essays and speeches on human rights, nationalism, and Philippine sovereignty, was published in 1987 by the Diokno Foundation. The collection is named after Diokno's popular speech, in which he says,

There is one dream that all Filipinos share: that our children may have a better life than we have had. So there is one vision that is distinctly Filipino: the vision to make this country, our country, a nation for our children.[27]

Several parts of the book are now accessible online, at The Diokno Foundation

Famous quotes

- "No cause is more worthy than the cause of human rights... they are what makes a man human. Deny them and you deny man's humanity."

- "There is one dream that we all Filipinos share: that our children may have a better life than we have had. To make this country, our country, a nation for our children."

- "Law in the land died. I grieve for it but I do not despair over it. I know, with a certainty no argument can turn, no wind can shake, that from its dust will rise a new and better law: more just, more human, and more humane. When that will happen, I know not. That it will happen, I know."

- "We are one nation with one future, a future that will be as bright or as dark as we remain united or divided."

- "Authoritarianism does not let people decide; its basic premise is that people do not know how to decide. It promotes repression that prevents meaningful change, and preserves the structure of power and privilege."

- "Yes-men are not compatible with democracy. We can strengthen our leaders by pointing out what they are doing that is wrong."

- "The point is not to make a perfect world, just a better one – and that is difficult enough."

- "Do not forget: We Filipinos are the first Asian people who revolted against a western imperial power, Spain; the first who adopted a democratic republican constitution in Asia, the Malolos Constitution; the first to fight the first major war of the twentieth century against another western imperial power, the United States of America. There is no insurmountable barrier that could stop us from becoming what we want to be."

- "All of us are Filipinos not only because we are brothers in blood, but because we are all brothers in tears; not because we all share the same land, but because we share the same dream."

- "Reality is often much more beautiful than anything that we can conceive of. If we can release the creative energy of our people, then we will have a nation full of hope and full of joy, full of life and full of love — a nation that may not be a nation for our children but which will be a nation of our children."

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Jose W. Diokno | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Diokno's second Senate term was cut short when he was jailed—without charges—by Ferdinand Marcos, immediately after the declaration of martial law.

- Gavilan, Jodesz (2017-09-21). "No cause more worthy: Ka Pepe Diokno's fight for human rights". Rappler. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- "Order of Lakandula award given to Diokno". Manila Bulletin. 2004-04-30. Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- Macariola, Monica (2004-02-26). "Nation remembers EDSA". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- Dalisay, Jose Jr. "Jose W. Diokno: The Scholar-Warrior". Archived from the original on 2013-04-14. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- Dumindin, Arnaldo. "Philippine–American War, 1899-1902". Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- "My Berenguer de Marquina Ancestry". Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- "Jose W. Diokno: Fleshing out a legend". Retrieved 2020-09-10.

- "Jose Diokno". Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- Dalisay, Jr., Jose (2011-05-23). "Jose W. Diokno: The Scholar-Warrior by Jose Dalisay, Jr".

- "DIOKNO, Jose W." 2015-10-15. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- Diokno, Maris (May 23, 2011). "Personal interview". Jose W. Diokno: The Scholar-Warrior by Jose Dalisay, Jr. (Interview). Interviewed by Jose Dalisay Jr. Manila: Facebook.

- "Carmen Diokno: Remembering an unsung heroine". Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- Ed Garcia (1993). Six Modern Filipino Heroes. Anvil Publishing. ISBN 978-9-712-70325-6. OCLC 31900385.

- "Diokno, Jose W."

- "The Philippines: Smoke in Manila". Time. August 10, 1962. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- De Guzman, Sara Soliven (2014-05-26). "A ghost from the past – the Stonehill scandal". Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- "Pepe Diokno, when comes such another?".

- "Republic Act No. 5186".

- Rodolfo, Cherry Lyn. "Directions for Industrial Restructuring in the Twenty-First Century: The Philippine Case" (PDF). UAP. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- "Observe Politics: THE LOST OF DOMINANCE OF THE NACIONALISTA PARTY DURING THE MARTIAL LAW AND POST-MARTIAL LAW". Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- Orellana, Faye. "LP members remember 1971 Plaza Miranda bombing". Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- "Socially Conscious: Lasallian accounts of activism in the Marcos era". Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- Paul J. Smith (March 26, 2015). Terrorism and Violence in Southeast Asia: Transnational Challenges to States and Regional Stability: Transnational Challenges to States and Regional Stability. Taylor & Francis. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-1-317-45886-9.

- T. J. S. George (1980). Revolt in Mindanao: The Rise of Islam in Philippine Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-580429-4.

- ""Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil?" by Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr". Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- Manalang, Priscila S., ed. (1987). A Nation for Our Children: Selected Writings of Jose W. Diokno. Quezon City: Jose W. Diokno Foundation. ISBN 971-91088-1-9.

- Daroy, Petronilo Bn. (1988). "On the Eve of Dictatorship and Revolution". In Javate-de Dios, Aurora; Daroy, Petronilo Bn.; Kalaw-Tirol, Lorna (eds.). Dictatorship and Revolution: Roots of People's Power. Metro Manila: Conspectus Foundation. pp. 1–25. ISBN 9919108018.CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

- Yamsuan, Cathy. "Enrile on fake ambush: 'For real'". Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- "Enrile's 'ambush': Real or not?". Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- "Marcos and his men: Who were the key Martial Law figures?". Retrieved 2020-10-01.

- "Declaration of Martial Law".

- "Defense Chief Unharmed".

- Cupin, Bea (2016-02-25). "#EDSA30: Remembering Alpha and Delta".

- "Mariz Diokno remembers two Joses".

- "THE URBAN MASS MOVEMENT IN THE PHILIPPINES, 1983-87" (PDF).

- Lane, Max (1990). "The Urban Mass Movement in the Philippines, 1983-87". Political and Social Change Monograph. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University. Department of Political and Social Change: 11. ISSN 0727-5994.

- Abinales, P.N. (1992). "Jose Maria Sison and the Philippine Revolution: A Critique of an Interface" (PDF).

- "APPENDIX: A HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINE POLITICAL PROTEST". Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- "The Fall of the Dictatorship".

- Te, Theodore. "[ANALYSIS | Deep Dive] Community legal aid service: Too much, too soon?". Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- Jones, Sidney (1995). "Regional Institutions for Protecting Human Rights in Asia". Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law). 89: 475–480. doi:10.1017/S0272503700085074. JSTOR 25658967. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- "Human Rights Declarations in Asia-Pacific". Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- Alfreðsson, Guðmundur (1995). A Thematic Guide to Documents on the Human Rights of Women: Global and Regional Standards Adopted by Intergovernmental Organizations, International Non-Governmental Organizations and Professional Associations. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-9-041-10094-8.

- "Tribute to Jose (Pepe) W. Diokno". 1988. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- Thoolen, Hans (2002-05-03). "Our History". Crete, Greece. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- "Miscellaneous". Commonwealth Law Bulletin. 9: 279–327. 1983. doi:10.1080/03050718.1983.9985708. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- "Tribute to Jose (Pepe) W. Diokno". 1988. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- "Letting in the light: 30 years of Torture Prevention" (PDF). Association for the Prevention of Torture. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Lorenzo M. Tañada". Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Nacional, Katherine. "JOSE WRIGHT DIOKNO" (PDF). Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "Jose W. Diokno: The Scholar-Warrior by Jose Dalisay, Jr". Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- Mydans, Seth (1987-03-01). "Jose W. Diokno, ex-Senator; Headed Manila Peace Panel". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- "To Sing Our own Song".

- Hollie, Pamela G. (1982-08-20). "MARCOS IRKED BY BBC FILM SHOWING CRITICS OF HIS RULE". Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- "Looking Beyond Marcos". Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Executive Order No. 236, s. 2003".

- "Proclamation No. 78, s. 1987". Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Ramirez, Joanne Mae M. (2005-03-08). "Incorruptible judge gets Pepe Diokno Award". Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- Ramirez, Joanne. "incorruptible judge gets Pepe Diokno Award". Philippine Star. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- Nacional, Katherine E. "Jose Wright Diokno" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- "Maris Diokno remembers two Joses".

- "Duterte: It's Russia, China, PH 'against the world'".

- "IS RODRIGO DUTERTE A RESURRECTED FERDINAND MARCOS? - BLUEBOARD BY CARMEL V. ABAO".

- "Philippines: Drop Sedition Cases Against Duterte Critics".

- "Philippines Continues March Towards Duterteship".

- Gang Badoy (host), Lourd de Veyra (host), Pepe Diokno (guest), Cyrus Fernandez (guest), others (2010-11-04). "The Last Episode". Rock Ed Radio. Ortigas Center, Pasig. Progressive Broadcasting Corporation. NU 107.

- "Phaidon Press: Take 100: The Future of Film". Archived from the original on 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2012-02-26.

- Diokno at IMDB

- "Marcos Said They 'Chose to Stay' in Prison". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2020-09-10.

- "'Ka Pepe' Diokno's spirit lives". The Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- José, F. Sionil (2011-05-23). "Defining Jose W. Diokno by F. Sionil Jose". Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- Encarnacion Tadem, Teresa S. "Interpreting Marcos' 'chief technocrat'". Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Diokno, Jose; Falk, Richard (1984). "On the Struggle for Democracy". World Policy Journal. 1 (2): 433–445. JSTOR 40209172. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- "LOOKING BEYOND MARCOS". Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- "Jose W. Diokno: The Scholar-Warrior by Jose Dalisay, Jr". Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Vilchez, Javier (2019-08-31). "Five forgotten heroes of the Philippine Senate". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

Further reading

- Alfreðsson, Guðmundur S. (1995). On the Eve of Dictatorship and Revolution. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-9-041-10094-8.

- Daroy, Petronilo Bn. (1988). On the Eve of Dictatorship and Revolution. Conspectus Foundation. ISBN 9919108018.CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

- Garcia, Ed (1993). Six Modern Filipino Heroes. Pasig, Metro Manila: Anvil Publishing. ISBN 978-9-712-70325-6.

- George, T.J.S. (1980). Terrorism and Violence in Southeast Asia: Transnational Challenges to States and Regional Stability. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-80429-4.

- Manalang, Priscila S. (1987). A Nation for Our Children: Selected Writings of Jose W. Diokno. Quezon City: Jose W. Diokno Foundation. ISBN 978-9-719-10880-1.

- Smith, Paul J. (2004). Revolt in Mindanao: The Rise of Islam in Philippine Politics. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-317-45886-9.