Central Park Tower

Central Park Tower, also known as the Nordstrom Tower, is a residential supertall skyscraper along Billionaires' Row on 57th Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Designed by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, the building rises 1,550 feet (472 m) and is the second-tallest skyscraper in the United States and the Western Hemisphere, the 13th tallest building in the world, the tallest residential building in the world, and the tallest building outside Asia by roof height.

| Central Park Tower | |

|---|---|

Seen in December 2020 | |

| |

| Alternative names | Nordstrom Tower |

| General information | |

| Status | Topped-out |

| Type | Residential, retail |

| Architectural style | Modern |

| Location | 225 West 57th Street Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°45′59″N 73°58′52″W |

| Construction started | September 17, 2014 |

| Estimated completion | 2021 |

| Cost | $3 billion |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 1,550 ft (472 m) |

| Top floor | 131 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 98 |

| Floor area | 1,285,308 square feet (119,409.0 m2) |

| Lifts/elevators | 11 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture |

| Developer | Extell Development Company |

| Structural engineer | WSP Global |

| Main contractor | Lendlease |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | November 10, 2009 |

| Reference no. | 2380 |

| Designated entity | B. F. Goodrich Company Building |

Central Park Tower was developed by Extell Development Company and Shanghai Municipal Investment Group. The lowest floors of the building contain a large Nordstrom store, the first in New York City. The eastern portion of the tower contains a cantilever above the Art Students League of New York's building at 215 West 57th Street, intended to maximize views of nearby Central Park. The residential portion of the tower contains 179 condominiums. In total, Central Park Tower cost $3 billion to construct.

The site of Central Park Tower was formerly occupied by two buildings at 225 West 57th Street and 1780 Broadway, which were demolished in 2011–2012. Despite uncertainty about the final design and complications relating to the tower's financing, excavations at the site started in May 2014, and actual construction started in February 2015. There were several incidents and controversies during the building's construction, including a controversy over the tower's cantilever and the death of a security guard. The building topped out during September 2019, with a projected completion date of 2021.

Site

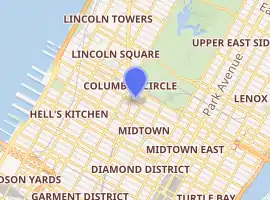

Central Park Tower is in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, just south of Columbus Circle, on the east side of Broadway between 57th Street to the south and 58th Street to the north. The northwestern corner of the building abuts 1790 Broadway, while the southwestern corner is adjacent to 1776 Broadway. Central Park Tower is also near 240 Central Park South and 220 Central Park South to the north; the American Fine Arts Society (also known as the Art Students League of New York building) and Osborne Apartments to the east; and 224 West 57th Street and the American Society of Civil Engineers' Society House to the south.[1]

Central Park Tower is one of several major developments around 57th Street and Central Park that are collectively dubbed Billionaires' Row by the media. Other buildings along Billionaires' Row include 432 Park Avenue five blocks southeast, 111 West 57th Street and One57 one block southeast, and the adjacent 220 Central Park South.[2][3][4]

Former buildings

In the 20th century, the area was part of Manhattan's "Automobile Row", a stretch of Broadway extending mainly between Times Square at 42nd Street and Sherman Square at 72nd Street.[5][6] The Hard Rock Cafe and Broadway Dance Center occupied the structure at 221 West 57th Street before that building was purchased by Central Park Tower's developer, the Extell Development Company, in 2006.[7]

On the western side of the building's base is the facade of the 12-story building at 1780 Broadway, which formerly contained the B. F. Goodrich Company showroom.[7][8] There was also an 8-story building at 225 West 57th Street,[9][10] which contained the Stoddard-Dayton showroom.[8][11] Both structures were built in 1909,[12] to designs by Howard Van Doren Shaw.[9][10] 1780 Broadway was one of the most visible buildings on Automobile Row because of the site's elevated topography,[10] and was leased to various automotive firms during the early 20th century.[13] Goodrich came to own both 1780 Broadway and 225 West 57th Street, but by the time the company sold the structures in 1928, they were collectively called the "Goodrich Building".[14] A single-story annex was built for the Lincoln Art Theatre in 1962–1964, and the Goodrich Building became a supermarket in the 1990s before being acquired by Extell in 2006.[15]

Design

Central Park Tower was developed jointly by Extell and Shanghai Municipal Investment Group.[16][17] It was designed by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture.[18][19][20] WSP Global was the structural engineer for the project, while Lendlease was the main contractor.[21]

Central Park Tower has 98 habitable floors,[22][21] though the top floor is numbered 131.[21][23] Its tallest habitable story is 1,417 feet (432 m) high.[21] The roof is 1,550 feet (470 m) above ground level.[21][23][24] This makes Central Park Tower the tallest primarily residential building in the world; the much taller Burj Khalifa has 900 residential units, but is mixed-use.[25] Central Park Tower is also the second-tallest skyscraper in the United States and the Western Hemisphere, the 13th tallest building in the world, and the tallest building outside Asia by roof height.[26] Due to its high slenderness ratio, the building has been characterized as part of a new breed of New York City "pencil towers".[27]

Facade

The facade of Central Park Tower was designed by James Carpenter Design Associates and Permasteelisa Group.[21] According to Gill and Smith, the glass cladding was intended to help the tower fit into the skyline.[28]

Main structure

The base of the tower along 57th and 58th Streets is made of glass, arranged into fluted panels that are insulated and laminated. The panels are installed in a serpentine "wave" pattern.[29][30][31] These glass panels have a total combined surface area of 52,700 square feet (4,900 m2).[30] The panels are set within aluminum frames and locked together with steel plates, fitting between the concrete floor slabs on each level.[32]

The upper stories' facade is mostly a curtain wall made of aluminum and glass.[23][28] The curtain wall is subdivided vertically by stainless steel "fins" that are arranged similarly to pinstripes; they resemble mullions but do not project from the facade. The spandrels between each floor are also clad with stainless steel.[28][29][30] According to Permasteelisa, 610,300 square feet (56,700 m2) of glass curtain wall was used on the upper floors.[30]

1780 Broadway

The facade of 1780 Broadway, a New York City designated landmark,[33][34] is preserved at the base of the tower on Broadway.[35] The landmark facade consists of one bay of windows on either side of a wide central bay.[15] The lowest two floors of 1780 Broadway are clad with granite and topped by a granite cornice. The central window opening of the second floor is flanked by granite columns, while the outer bays contain trimmed rectangular window frames with carved bands.[36] On each of the third through 11th floors, the central bay contains four windows within a granite frame, with a brick surround and single window on either side. There is a small cornice above the central bay on the third floor, and a sill above the 11th floor of the landmark facade. The 12th floor is clad with brick and contains a decorative balcony in the central bay.[37]

Structural features

In order to maximize views of Central Park, whose southern border is one block north, Extell built a cantilever extending 28 feet (8.5 m) from the eastern side of the tower. The cantilever starts roughly 300 feet (91 m) above the Art Students League of New York's building at 215 West 57th Street, and covers roughly one third of the space above the Art Students League building.[38] Without the cantilever, Vornado Realty Trust's under-construction 220 Central Park South would have blocked the lowest 950 feet (290 m) of the tower.[39][40] In conjunction with a 2013 agreement with Vornado that involved shifting 220 Central Park South slightly to the west, this gave Central Park Tower direct views of Central Park.[39][41] Atop the building is a weighting system to balance the building against the wind.[42]

Interior

The building has a gross floor area of 1,285,308 square feet (119,409.0 m2).[21] The first seven floors of the tower are anchored by New York City's first Nordstrom department store.[43] Floors eight to twelve house amenity spaces for residents.[44] There are eleven elevators serving the upper floors.[21] These elevators, developed by Otis Worldwide, travel 2,000 feet per minute (610 m/min).[42] The entrance for Nordstrom is on 57th Street while the residents' entrance is on 58th Street.[45]

Condominiums

The building contains 179 condominiums starting on the 32nd floor.[28][42] Each unit has between two and eight bedrooms, with between 1,435 to 17,500 square feet (133.3 to 1,625.8 m2) of floor area.[18] The average apartment spans 5,000 square feet (460 m2).[46] As indicated by offering plans in 2017, the cheapest apartment was a $1.5 million studio,[47] while twenty of the largest units were being sold at over $60 million each.[46] A triplex penthouse at the top of the building spans 17,000 square feet (1,600 m2) across the 129th through 131st floors.[48] This penthouse contains its own gym, ballroom, library, and observatory; the penthouse's price has not been publicly disclosed.[47]

The interiors of the building's condominiums were designed by Rottet Studio.[18][49] The units have open layouts and floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Central Park or other nearby structures.[22][46][50] Interior features include Miele and Sub-Zero appliances, custom cabinetry, and white oak floors.[22][51]

Amenities

There are 50,000 square feet (4,600 m2) of amenities on the 8th through 12th floors.[50][52] On the 14th floor, the building features the “Central Park Club” with a lounge, theater, conference room, play area, and tween lounge. A landscaped terrace designed by HMWhite contains an 60-foot (18 m) outdoor pool with pergolas and trellises, a central lawn, and two gardens.[18][52][53] On the 16th floor, there is an indoor pool, exercise room, spa, gym, basketball court and children's playroom.[18][50]

There is also a three-floor private club named "The 100th Floor" near the building's apex, marketed as the highest private club in the world.[54] The space contains a 126-person ballroom, a cigar bar, and a private dining room.[42][46][49]

Nordstrom

A Nordstrom department store occupies roughly 285,000 square feet (26,500 m2) of the building's first five floors as well as two basement levels. The store spans 360,000 square feet (33,000 m2) in total, including space at 5 Columbus Circle and 1776 Broadway.[32][55] The Nordstrom location has an open plan for its floors, as well as 19-foot (5.8 m) ceilings. The floors are lit by the wavy glass facades of the base at 57th and 58th Streets.[31] Other design features include halo reveals around each column, railings wrapping around corners, and a terracotta wall near the elevators that resemble the wavy facade.[32] The store also contains six bars and restaurants, including two operated by celebrity chef Tom Douglas.[31][56]

History

Land acquisition

Extell started its land acquisition for what would become the Central Park Tower in mid-2005. Extell purchased 221 West 57th Street and a neighboring lot for $67.5 million, yielding over 261,000 square feet (24,200 m2) of buildable space.[7] That September, Extell served one of 221 West 57th Street's occupants, the Broadway Dance Center, a notice of default for operating without the required public assembly permit. Extell also revoked the Center's use of the building's internal staircases due to theft concerns and offered the Center $1 million to move to a new home on 55th Street.[57] Extell purchased 136,000 square feet (12,600 m2) of air rights from the Art Students League of New York in early 2006 for $23.1 million,[38][58][59] and later paid the Art Students League another $31.8 million for 6,000 square feet (560 m2) of air rights.[38]

Further air rights purchases followed in 2006 and 2007. This included 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) of air rights above the Osborne Apartments on 205 West 57th Street, in January 2006; another 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) of air rights from the Saint Thomas Choir School at 202 West 58th Street, in November 2006; and 14,290 square feet (1,328 m2) of air rights from the 13-story apartment building at 200 West 58th Street, in January 2007. In addition, Extell gained 156,000 square feet (14,500 m2) of development rights from the purchase of 1780 Broadway and two contiguous properties, and 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2) of development rights from the purchase of a plot of 58th Street, in two separate 2006 purchases. Combined, these purchases allowed a building with up to 563,000 square feet (52,300 m2) of floor area.[7]

In mid-2012, Extell purchased the neighboring building at 223 West 58th Street for $25 million.[60] In July 2013, Extell paid $25 million for the lot at 232 West 58th Street, adding another 20,750 square feet (1,928 m2) of development rights, and thus completing the site.[7] That October, Extell purchased 90,000 square feet (8,400 m2) of air rights from the Atlantic Development Group.[7]

Attempted preservation of existing structures

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) attempted to protect 225 West 57th Street and the neighboring 1780 Broadway in 2009, after having unsuccessfully attempted to designate the structures as city landmarks in 1994.[34] After Extell and New York City Council Speaker Christine Quinn pushed back, the LPC dropped its proposal to designate 225 West 57th Street as a landmark.[61] In an LPC hearing, almost all parties except for the Real Estate Board of New York supported designating 1780 Broadway as a landmark. However, the proposed designation of 225 West 57th Street received both significant support and opposition: the American Institute of Architects, New York State Assembly member Richard N. Gottfried, and the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois spoke in favor of that building's designation while City Council members Melinda Katz, Daniel Garodnick, and Jessica Lappin spoke against landmark status.[33]

On November 10, 2009, the LPC voted 6–3 to preserve 1780 Broadway's facade and tear down everything else. The three dissenting members of the LPC had wanted 225 West 57th Street to be preserved as well.[61][33] Preservation groups like the Historic Districts Council and New York Landmarks Conservancy expressed dissatisfaction that City Council members had influenced the decision by saying they would veto any LPC designation for the properties if 225 West 57th Street was protected.[62][63] The last tenant of 1780 Broadway moved out of that building in April 2011.[9] Extell had demolished 225 West 57th Street in 2011,[64] and destroyed the interiors of 1780 Broadway at the end of 2012.[65]

Early construction

By mid-2012, Nordstrom committed to occupying 225,000 square feet (20,900 m2) at the base of Extell's proposed tower, paying a $102.5 million down payment for the first five floors and the two basement floors.[60] At the end of 2012, Extell revealed that Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill would design the tower and that it would rise 1,550 feet (470 m) to become the second-tallest building in New York City.[66] Adrian Smith's firm, which had been recommended by Nordstrom, beat out other contenders for the design including Herzog & de Meuron, SHoP Architects, Jean Nouvel, Foster and Partners, and Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.[67] At the time, the building was expected to rise 1,250 feet (380 m), open in 2018, and contain a hotel on the seventh through twelfth floors.[66] By November 2013, Extell had demolished all the previous buildings on the site.[68]

The company began excavating the building's 80 feet (24 m) deep foundations in May 2014.[69] A new design for the tower was leaked in July 2014 that revealed a 1,479-foot-tall (451 m) tower with a spire reaching 1,775 feet (541 m), just a foot shy of One World Trade Center's pinnacle.[70] After nearly a year of excavation, the building's concrete foundation was poured in February 2015.[71] New renderings were revealed on April 20, 2015, showing a roof height of 1,530 feet (470 m) and an architectural height of 1,775 feet (541 m) with the spire.[72] However, new permits filed several months later showed the building without a spire but increased the roof height to 1,550 feet (470 m). At the same time, the building's official name of "Central Park Tower" was unveiled and the completion date was pushed back to 2019.[73] The building's tower crane was installed in July 2015[74] and the structure reached street level by the end of September.[75] The structural steel for Nordstrom's retail base was complete by the middle of 2016.[76]

Financing difficulties

Extell took out a $300 million mortgage from The Blackstone Group on the land in mid-2012. The new mortgage allowed Extell to repay a $250 million loan from HSBC on the site's existing properties.[60] In June 2016, Extell announced it were seeking to raise $190 million in financing for the tower from foreign investors through the EB-5 visa program.[77] The company had previously raised $400 million by selling the retail portion to Nordstrom and another $300 million by issuing bonds on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange.[78] Around the same time, Extell also brought in the Shanghai Municipal Investment Group (SMI) as an additional equity investor for roughly $300 million.[79] Though the Blackstone loan had faced maturation in August 2016,[16] Extell used the extra cash to repay $50 million of the loan and extend the maturity on the remainder,[16] to December 9, 2016.[80]

Even after the additional capital was secured, Extell still needed to receive a loan of roughly $1 billion by May 2017, or SMI could exercise a put option to force Extell to repay SMI's equity investment with interest.[79] Additionally, the interest rate on Extell's bonds on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange rose from 6% to 16%, effectively turning them into junk bonds.[81] If Extell defaulted on Blackstone's loan, its interest rate would increase from 8% to 14%, but Blackstone was only willing to grant Extell a one-week extension on its land loan to December 17.[80] The day the land loan was due, Extell closed a new $235 million bridge loan with JPMorgan Chase and hedge funds Fortress Investment Group and Baupost Group in order to repay Blackstone.[82]

By March 2017, Extell disclosed that it had spent $939 million on the development of the tower since 2014, including over $300 million in 2016 alone.[83] The tower's completion date was also pushed back another year to November 2020. At the same time, Nordstrom invested another $25 million, with a put option that allowed the company to force Extell to repurchase the store space if it was not ready by December 2018. A further $168 million came from EB-5 investors.[83] In May 2017, SMI changed the terms for its equity investment, so that Extell could keep looking for a construction loan until the end of 2017.[84] That June, Israeli bondholders became concerned that Extell would be unable to meet its bond obligations as it held only $120 million in cash, still had not closed a construction loan, and still had its bonds classified as junk bonds with a 13% interest rate.[85] A month later, over 40 private and institutional bondholders met to discuss whether to force early repayment on the bonds. Extell was scheduled to repay $180 million in December 2018 but investors were worried that the company could not raise the cash, as the declining luxury market had made the unit pricing unrealistic.[86]

Following the bondholder's meeting, Extell signed a term sheet for a $900 million construction loan with JPMorgan Chase in August 2017.[87] That same month, an Israeli bond rating agency downgraded the credit ratings for all of Extell's bonds after the company revealed it had just $36 million in cash on hand.[84] Extell stated that it intended to close on the loan with JPMorgan before the end of the year, but the cash on hand would not be able to sustain construction through 2018 without a loan.[84] SMI also agreed to push back the deadline on their put option for a third time, from December 2017 to June 2018.[88] At the end of 2017, Extell announced it closed on $900 million in construction financing from JPMorgan Chase and an additional $235 million preferred equity investment from a hedge fund. The preferred equity carried an interest rate of 11% while the senior loan carried the high rate of Libor plus 4.5%. JPMorgan required repayment of the loan by December 2021 and also stipulated that Extell must sell $500 million worth of apartments by December 2020 or face default.[89] In March 2018, Extell announced they would be selling 17% of the equity in the tower to a group of investors for $107 million,[90] sparking another downgrade of Extell's bonds.[91]

Completion

At the end of May 2017, Extell received approval to begin sales at Central Park Tower,[92] with a total targeted $4.02 billion sellout for the project's 179 condominiums.[93] The average unit price of $22.5 million was twice as much as the average sales price for a top New York City luxury apartment.[94] Extell hoped to sell 20 of the units for more than $60 million a piece, including a $95 million penthouse.[95] The first glass was installed on the building in September 2017 when the building was roughly a third of the way to its peak.[96] The tower reached the 1,000-foot (300 m) mark in the spring of 2018 and was approximately 1,300 feet (400 m) tall by the end of the year.[97][98] In October 2018, Extell officially launched sales at the project.[99]

By the end of 2018, Extell had spent $1.7 billion on construction of the tower and expected to spend another $1.3 billion before the building opened. This total project cost of $3 billion was over $1 billion higher than the $1.9 billion that Extell expected construction to cost in 2016.[100] Extell also increased the projected sellout of the building's condominiums to $4.5 billion or $7,450 per square foot, up from projections of $4.02 billion in May 2017 and higher even than the $4.4 billion in sales Extell expected in 2016. The company also unveiled new buyer's incentives, offering to waive between three and five years of common charges and pay 50% of broker's commissions.[101][102] In interviews in 2019, Extell founder Gary Barnett said that condominiums were not selling as quickly as at Extell's previous One57 development during the early 2010s, when there were no other luxury developments nearby. Barrett signaled an openness to discounting units to increase sales in addition to the existing buyer's incentives.[42][103][104] While Barnett did not disclose sales numbers, he said that half of the buyers would be "English speakers" and the other half would be foreign buyers.[42]

Central Park Tower surpassed 432 Park Avenue in height during March 2019, reaching 1,400 feet (430 m).[105] Two months later, the building's first condominiums were publicly listed for sale.[52] The tower reached over 1,450 feet (440 m) by the end of July 2019, surpassing Willis Tower in Chicago.[106] Central Park Tower topped out on September 17, 2019, the same day as One Vanderbilt.[18][28][107] By the end of the year, the building's glass curtain wall had been almost completely installed.[108] The Nordstrom store was the first part of the Central Park Tower to be finished, opening on October 24, 2019.[109][110] Construction was temporarily halted in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City.[111][112] By late 2020, the construction crane was being disassembled,[113] and the first residents started moving into Central Park Tower.[114] While some media sources reported that Central Park Tower was completed by the end of 2020,[115][116] finishes were still being applied through 2021, and an official completion had not been announced.[117]

Incidents and controversies

Art Students League cantilever controversy

The cantilever over the Art Students League of New York's building at 215 West 57th Street was controversial. In October 2013, Manhattan Community Board 5 voted against allowing the cantilever, although the vote was merely advisory and final power over the decision rested with the LPC.[118] Weeks later, the LPC approved the air rights sale and cantilever in a 6-1 vote.[119] At the same meeting, Extell revealed a revised design which would rise 1,423 feet (434 m) tall.[120] In February 2014, the Art Students League also approved the deal in a 1,342-227 vote among all members despite opposition from several third parties including the Municipal Art Society.[121][122] Afterwards, over 100 members of the Art Students League filed suit against Extell and the Art Students League organization itself to attempt to stop the air rights sale, but the lawsuit was dismissed in mid-2014.[123]

In January 2016, three hundred members of the League sued the League's leadership, claiming that instructions on how to vote on the sale were misleading and that the publicized voting procedure was not followed correctly. According to the lawsuit, materials distributed by the League's leadership indicated that abstaining from voting would count the same as a "no" vote which allegedly led many members not to vote on the issue. If non-voting members' decisions were counted as "no" votes, the tally should have been 2,603–1,342 against the air rights sale.[124] The second lawsuit was dismissed through summary judgment when a judge ruled that the League's leadership had acted in good faith while interpreting the League's by-laws regarding voting procedures. An appeals court upheld the decision in March 2016, as construction had progressed to a point where it could not be undone without causing undue hardship that would cost Extell more than $200 million.[125]

Construction incidents

On July 12, 2017, a 4,300-pound (2,000 kg) crate containing window panes fell from the building's 16th floor after a ramp connecting the construction hoist to the building collapsed. The New York City Fire Department closed 58th Street for the rest of the day to investigate.[126]

On December 18, 2019, ice falling from Central Park Tower injured a pedestrian, who required hospitalization.[127][128] Multiple blocks near the building were closed to traffic and pedestrians by the Department of Emergency Management, and the Department of Buildings stopped construction on the building indefinitely.[129] The falling ice was considered problematic because ice sliding down a flat facade, such as that of Central Park Tower, could reach a maximum speed of 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) from a height of as little as 15 stories.[130]

Security guard death

On May 26, 2018, a teamster attempted to move a piece of ducting with a forklift and accidentally hit a 3,000-pound (1,400 kg) glass panel at the ground floor. The panel tipped over on top of 67-year-old security guard Harry Ramnauth.[131] A construction worker at the scene ended up fracturing his right foot when he tried to rescue Ramnauth.[132][133] Although Emergency medical technicians arrived eleven minutes after the incident, Ramnauth was pronounced dead at the hospital, and an autopsy listed his cause of death as blunt force trauma of the neck and torso.[134] After the incident, the New York City Department of Buildings ordered a temporary halt to construction, though work soon resumed.[135][136] Ramnauth's family also sued Extell, contractor Pinnacle Industries, and the developer's insurer AIG for the pain and suffering Ramnauth endured between the time the glass panel fell on him and when he lost consciousness six to eight minutes later. The family proposed a $4.75 million settlement, but Extell initially refused.[131] In January 2020, Lendlease Group, contractor Pinnacle Industries, and Extell paid the guard's family $1.25 million to settle the family's wrongful death claim.[137]

Following an investigation by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), both Lendlease and subcontractor Permasteelisa North America were cited and fined $12,934 each. According to OSHA, the contractors failed to keep the construction site's aisles and passageways clear so that material handling equipment or employees could move freely, leading to Ramnauth's death.[138] Both contractors filed disputes with OSHA's findings and appealed the fines. Lendlease was also fined $25,000 by the New York City Office of Administration Trials and Hearings for failing to adequately safeguard the construction site. In 2020, Lendlease filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the City's findings, both because Ramnauth was not considered a member of the public and because the city did not conduct an investigation until three days after the incident.[137]

See also

References

Citations

- "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- Satow, Julie (June 27, 2014). "Moving In, Slowly, to 'Billionaires' Row'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- Willett, Megan (September 2, 2014). "The New Billionaires' Row: See the Incredible Transformation of New York's 57th Street". Business Insider. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Goldberger, Paul (May 2014). "Too Rich, Too Thin, Too Tall?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Dunlap, David W. (July 7, 2000). "Street of Automotive Dreams". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, p. 2.

- Bockmann, Rich (October 1, 2015). "Assembling a monster tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Horsley, Carter (November 9, 2009). "Landmarks commission considering designation of two Extell properties in west Midtown". CityRealty. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- Barron, James (May 16, 2011). "Once a Bustling Automobile Row Anchor, Now Empty". City Room. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, p. 5.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, p. 6.

- "Realty Still in Demand in Automobile District; Purchase of $300,000 Building East Week -- Tendency of Large Concerns to Become Owners Instead of Tenants". The New York Times. February 21, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, pp. 6–7.

- Clark, Evans (April 29, 1928). "Uncle Sam Now World's Business Man; American Companies Have Established Their Own Factories and Branches in Every Quarter of the Globe and Have Obtained Vast Foreign Holdings to Supply Themselves With Raw Materials". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, p. 7.

- Carmiel, Oshrat (August 15, 2016). "Chinese Fund NYC's Tallest Residential Skyscraper—at a Price". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "Central Park Tower, Tallest Residential Building In The World, Launches Sales" (Press release). Extell Development Company; Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture; Shanghai Municipal Investment. PR Newswire. October 15, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Central Park Tower becomes world's tallest residential skyscraper". Dezeen. September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Rosenberg, Zoe (February 25, 2019). "Central Park Tower architect calls building 'respectful' of NYC skyline". Curbed NY. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- McGrath, Katherine. "New York City's Central Park Tower Just Became the World's Tallest Residential Building". Architectural Digest. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Central Park Tower". The Skyscraper Center. April 7, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Warren, Katie (August 20, 2020). "The world's tallest residential tower in NYC just released the first photos showing what its multimillion-dollar residences look like". Business Insider. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Central Park Tower". Emporis. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Premises: 217 WEST 57 STREET MANHATTAN". bisweb. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- "World's tallest residential skyscraper tops out in NYC". Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "100 Future Tallest Buildings in the World". The Skyscraper Center. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Wainwright, Oliver (February 5, 2019). "Super-tall, super-skinny, super-expensive: the 'pencil towers' of New York's super-rich". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- "Central Park Tower tops out to become the world's tallest residential building". The Architect’s Newspaper. September 18, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- "Central Park Tower". Surface Design. May 15, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Central Park Tower". www.permasteelisagroup.com. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Gannon, Devin (June 12, 2019). "Nordstrom's 7-level flagship opens at Central Park Tower next week". 6sqft. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Brandon, Elissaveta M. (January 31, 2020). "Nordstrom's Manhattan Flagship Unites Historic Landmarks and Contemporary Forms". Metropolis. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, p. 1.

- Chan, Sewell (November 10, 2009). "Divided Landmarks Panel Splits Decision on Midtown Buildings". City Room. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- Warerkar, Tanay (February 12, 2016). "Central Park Tower's Nordstrom Flagship Gets Its First Render". Curbed NY. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, pp. 7–8.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2009, p. 8.

- Kaminer, Ariel (September 23, 2014). "A Tower Will Rise Next to, and Over, a Paint-Spattered Landmark". ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Bagli, Charles V. (October 15, 2013). "Developers End Fight Blocking 2 More Luxury Towers in Midtown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- "Approved: 217 West 57th Street". New York Yimby. February 20, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Brown, Eliot (October 16, 2013). "Deal Settles Dispute Between Extell, Vornado". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- Frank, Robert (September 18, 2019). "What it's like to live on the 123rd floor of the world's tallest condo tower". CNBC. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- Izzy, Grinspan (June 28, 2012). "Nordstrom Will Open on W.57th Street Sometime Around 2018". Racked. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- "Nordstrom Tower to be World's Tallest Residential Building". Racked. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- "217 West 57th Street". therealdeal.com. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Gannon, Devin (December 7, 2017). "New renderings revealed for Extell's Central Park Tower as it hits halfway mark". 6sqft. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Warerkar, Tanay (July 7, 2017). "Central Park Tower's sprawling floorplans, exorbitant prices are unveiled". Curbed NY. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Gannon, Devin (March 27, 2017). "Extell's Central Park Tower will have a $95M penthouse and 100th-floor ballroom". 6sqft. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- Colman, Michelle (July 3, 2018). "Central Park Tower Reaches Supertall Status, See Never-Before-Seen Photos". CityRealty. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Mazzarella, Michelle (January 18, 2019). "First Look Inside the World's Highest Apartments at Central Park Tower". CityRealty. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Hylton, Ondel (July 11, 2017). "Central Park Tower's Luxurious Details Uncovered; Ballrooms, Observatories, Private Pools & More". CityRealty. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Warren, Katie (June 10, 2019). "Here's what the tallest residential building in NYC will look like when it's completed in 2020". Business Insider. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Gannon, Devin (October 5, 2017). "REVEALED: Central Park Tower's 'Village Green' lawn and pool deck". 6sqft. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Inside Extell's private club for the 0.1%". The Real Deal. January 27, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gannon, Devin (June 12, 2019). "Nordstrom's 7-level flagship opens at Central Park Tower next week". 6sqft. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Vianna, Carla (June 11, 2019). "Nordstrom's New Seven-Story Store Will Have Restaurants from Big-Deal Seattle Chefs". Eater New York. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- Kinetz, Erika (November 23, 2005). "Embattled With Landlord, Dance Studio May Lose Its Home". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Horsley, Carter (February 9, 2006). "Extell buys air-rights from Art Students League on West 57th Street". CityRealty. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Extell Buys Air Rights For Big New York Redevelopment". Real Estate Finance and Investment: 1. January 9, 2006 – via ProQuest.

- Weiss, Lois (August 27, 2013). "Nordstrom buys land for tower in Midtown". New York Post. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Brown, Elliot (November 10, 2009). "After Push by Extell, Landmarks Backs Down Over West 57th Street Building". New York Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Pogrebin, Robin (November 18, 2009). "City Council Influences Landmarks Decision". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Solomon, Serena (November 10, 2009). "Columbus Circle Development Clears Landmark Hurdle". DNAinfo. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Barron, James (May 16, 2011). "Once a Bustling Automobile Row Anchor, Now Empty". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Chaban, Matt (December 3, 2012). "Demolition Begins on 1780 Broadway, Final Piece of Barnett's 1,550-Foot 57th Street Tower". New York Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Brown, Elliot (December 16, 2012). "Extell's Chief Thinking Tall For Midtown". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Chaban, Matt (May 10, 2012). "Gary Barnett on How He Chooses His Designers and the 1,250-Foot Starchitect Tower Planned for Broadway and 57th". New York Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (May 2, 2014). "Construction Update: 217 West 57th Street & 220 Central Park South". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (November 8, 2013). "Construction Update: 217 West 57th Street". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (July 9, 2014). "Nordstrom Tower To Become World's Tallest Residential Building At 1,775 Feet". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (February 13, 2015). "Foundation Work Continues At 217 West 57th Street And 220 Central Park South". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (April 20, 2015). "Revealed: 217 West 57th Street, Official Renderings For World's Future Tallest Residential Building". New York Yimby. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- Fedak, Nikolai (September 8, 2015). "Nordstrom Tower Has Lost Its Spire, Will Stand 1,550 Feet Tall". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (July 6, 2015). "Tower Crane Arrives At 217 West 57th Street, Aka Nordstrom Tower". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (September 29, 2015). "Nordstrom Tower's Core Rises Above Street Level At 217 West 57th Street". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (May 23, 2016). "Construction Update: Supertall 217 West 57th Street, A.K.A. Central Park Tower". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Clarke, Katherine (June 21, 2016). "Extell looks to raise $190M in EB-5 funds for Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Solomon, E.B. (January 6, 2016). "Extell in talks with capital partner for Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Clarke, Katherine; Parker, Will (August 1, 2016). "Extell looks to have brought in Chinese equity partner at Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Clarke, Katherine (December 13, 2016). "Extell secures one-week extension on $235M Blackstone loan". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Clarke, Katherine (October 5, 2016). "Inside Gary Barnett's game of real estate Tetris". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Clarke, Katherine (December 16, 2016). "Extell to refi $235M land loan at Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (March 29, 2017). "Extell secures $168M in EB-5 funds for Central Park Tower; project's completion date pushed back". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (August 27, 2017). "Extell bonds downgraded in Israel, but remain low risk". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (June 21, 2017). "'Wait. Wait. Extell is a terrible company, but they want our properties?'". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (July 6, 2017). "Extell bondholders could force early repayment on Barnett's bonds". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Maurer, Mark (June 23, 2017). "The priciest condo project in New York history is finalizing a $900M loan". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (August 29, 2017). "SMI extends the deadline for financing Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (January 1, 2018). "Barnett closes on $1B-plus financing for Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (March 13, 2018). "Extell sells $107M in shares at its $4B Central Park Tower condo project". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Solomon, E.B. (March 21, 2018). "Wanted: Sales director at Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Plitt, Amy (June 1, 2017). "Central Park Tower is now one step closer to launching sales". Curbed. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Solomon, E.B. (May 21, 2015). "What could Gary do? Analyzing Extell's $4.4B sellout at the Nordstrom Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Parker, Will (May 31, 2017). "Central Park Tower, NYC's first $4B condo, can now launch sales". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Solomon, E.B. (July 7, 2017). "Revealed: Inside Gary Barnett's $4B tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (September 11, 2017). "217 West 57th Street, Aka Central Park Tower, Gets Its First Glass". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Nelson, Andrew (April 30, 2018). "Central Park Tower, Country's Tallest Building Under Construction, Officially Reaches Supertall Territory". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Young, Michael (December 31, 2018). "Central Park Tower Approaches 1,550-Foot Pinnacle, Nears Tallest Roof Height In New York City & The Western Hemisphere". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Solomon, E.B. (October 15, 2018). "Sales officially launch at Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Gourarie, Chava (April 4, 2019). "All in Good TASE: The Crisis for the American Cohort in Tel Aviv Is Essentially Over". Commercial Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Schulz, Dana (January 18, 2019). "Can Extell make Central Park Tower the most expensive condo in U.S. history?". 6sqft. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Slomont, E.B. (November 29, 2018). "To lure buyers, Extell offers free common charges for up to five years". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- Carmiel, Oshrat; Hurtado, Viviana (September 6, 2019). "Manhattan's Tallest Condo Building Joins a Swamped Luxury Market". Bloomberg News. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- Solomont, E.B. (December 31, 2019). "Gary Barnett gets candid about the condo boom of the 2010s and what's to come". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Young, Michael (March 25, 2019). "Central Park Tower Surpasses 432 Park Avenue To Become The Tallest Residential Building In The Western Hemisphere". New York YIMBY. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Young, Michael (July 29, 2019). "Central Park Tower Surpasses Chicago's Willis Tower On Way To Tallest Roof Height In Western Hemisphere". New York YIMBY. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Young, Michael (September 17, 2019). "Central Park Tower Officially Tops Out 1,550 Feet Above Midtown, Becoming World's Tallest Residential Building". New York YIMBY. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- Young, Michael (December 31, 2019). "Central Park Tower's Glass Curtain Wall Nears Completion In Midtown". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Nordstrom's Manhattan Flagship Store Officially Opens for Business in Central Park Tower". New York Yimby. October 28, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- "Check out the cocktail bar at Nordstrom's new Billionaires' Row flagship". 6sqft. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- "Construction of US $4bn Central Park Tower in New York halted". Construction Review Online. March 25, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- "Extell Suspends Construction on Central Park Tower". Commercial Observer. March 24, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Central Park Tower's Construction Crane Begins Disassembly Above Billionaires' Row". New York YIMBY. September 14, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Neubauer, Kelsey (January 4, 2021). "8 Major NYC Projects Set To Deliver In 2021". Bisnow. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- "Dramatic drop in skyscrapers built in 2020 as coronavirus impacts global construction". Dezeen. January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- MENAFN. "Dubai's iconic skyline welcomes 12 new skyscrapers". menafn.com. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Young, Michael (December 31, 2020). "Central Park Tower aka 217 West 57th Street Set for 2021 Completion in Midtown, Manhattan". New York YIMBY. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Velsey, Kim (October 11, 2013). "Community Board Rejects Extell's Plan to Cantilever Skyscraper Over Landmarked Art Students League". New York Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Extell cleared to cantilever 1,550-foot Nordstrom tower". The Real Deal. October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (October 2, 2013). "Revealed: Extell's 1,423-Foot Nordstrom Tower". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Velsey, Kim (February 13, 2014). "Art Students League Approves Extell Cantilever". New York Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Fedak, Nikolai (October 22, 2013). "Approved: The Nordstrom Tower". New York Yimby. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Moses, Claire (July 25, 2014). "Judge dismisses Art Students League suit over Extell tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Mashberg, Tom; Moynihan, Colin (January 18, 2016). "At Art Students League, Air Rights and Airing Grievances". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Denno, Jesse (March 16, 2016). "Suit Against Art Students League Board Decision To Sell Air Rights Fails On Appeal". CityLand. New York Law School. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Brenzel, Kathryn (July 12, 2017). "Ramp falls 16 stories from Extell's Central Park Tower construction site". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Sundstrom, Mark (December 18, 2019). "Falling ice hits, injures person near Columbus Circle: FDNY". Pix11 News. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Roberts, Georgett; Meyer, David (December 19, 2019). "Falling ice forces street closures near Columbus Circle". New York Post. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Roberts, Georgett (December 19, 2019). "Falling ice forces street closures near Columbus Circle". New York Post. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Paybarah, Azi (December 24, 2019). "Why Ice Is Falling From Glass Skyscrapers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Gartland, Michael (October 21, 2019). "Family of NYC security guard crushed by glass in horrific Billionaires' Row construction accident locked in ugly legal war over death". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "Security guard dies after falling glass from Central Park Tower skyscraper strikes him". New York Daily News. May 26, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "One man killed, one injured by falling glass panel at midtown construction site, authorities say". am New York. May 26, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- Baird-Remba, Rebecca (November 13, 2019). "A Construction Death on Billionaire's Row Shines Light on NY's Wrongful Death Law". Commercial Observer. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- "City suspends construction on Midtown skyscraper after falling glass killed security guard". New York Daily News. May 27, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Stop Work Order Issued at Skyscraper Construction Site After Death". NBC New York. May 27, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Brenzel, Kathryn; Diduch, Mary (January 23, 2020). "Lendlease disputes city's penalty in 2018 death at Central Park Tower". The Real Deal. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- Slowey, Kim (January 27, 2020). "Lendlease sues NYC building department over death citation". Construction Dive. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

Sources

- "B. F. Goodrich Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 10, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Central Park Tower. |

- Official website

- "Central Park Tower". CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- Central Park Tower at Emporis

- "Central Park Tower". SkyscraperPage.