14th Street–Union Square station

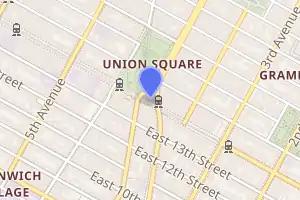

14th Street–Union Square is a New York City Subway station complex shared by the BMT Broadway Line, the BMT Canarsie Line and the IRT Lexington Avenue Line. It is located at the intersection of Fourth Avenue and 14th Street, underneath Union Square in Manhattan. The complex sits on the border of several neighborhoods, including the East Village to the southeast, Greenwich Village to the south and southwest, Chelsea to the northwest, and both the Flatiron District and Gramercy Park to the north and northeast. The 14th Street–Union Square station is served by the 4, 6, L, N, and Q trains at all times; the 5 and R trains at all times except late nights; the W train on weekdays; and <6> train weekdays in the peak direction.

14 Street–Union Square | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Station entrance within Union Square Park | |||||||||||

| Station statistics | |||||||||||

| Address | East 14th Street, Park Avenue South & Broadway New York, NY 10003 | ||||||||||

| Borough | Manhattan | ||||||||||

| Locale | Union Square, Gramercy | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°44′05″N 73°59′25″W | ||||||||||

| Division | A (IRT), B (BMT) | ||||||||||

| Line | BMT Broadway Line BMT Canarsie Line IRT Lexington Avenue Line | ||||||||||

| Services | 4 5 6 L N Q R W | ||||||||||

| Transit | |||||||||||

| Structure | Underground | ||||||||||

| Levels | 3 | ||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||

| Opened | July 1, 1948[1] | ||||||||||

| Station code | 602[2] | ||||||||||

| Accessible | |||||||||||

| Traffic | |||||||||||

| 2019 | 32,385,260[3] | ||||||||||

| Rank | 4 out of 424[3] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

14th Street–Union Square Subway Station (IRT; Dual System BMT) | |||||||||||

| MPS | New York City Subway System MPS | ||||||||||

| NRHP reference No. | 05000671[4] | ||||||||||

| Added to NRHP | July 6, 2005 | ||||||||||

The Lexington Avenue Line platforms were built for the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) as an express station on the city's first subway line, which was approved in 1900. The station opened on October 27, 1904, as one of the original 28 stations of the New York City Subway. As part of the Dual Contracts, the Broadway Line platforms opened in 1917 and the Canarsie Line platform opened in 1924. Several modifications have been made to the stations over the years, and they were combined on July 1, 1948. The complex was renovated in the 1990s and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.

The Lexington Avenue Line station has two abandoned side platforms, two island platforms, and four tracks, while the parallel Broadway Line station has two island platforms and four tracks. The Canarsie Line station, crossing under both of the other stations, has one island platform and two tracks. Numerous elevators make most of the complex compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA). The Lexington Avenue Line station, serving the 4, 5, 6, and <6> trains, is not ADA-accessible. In 2016, over 34 million passengers entered this station, making it the fourth-busiest station in the system.[3]

History

First subway

Planning for the city's first subway line dates to the Rapid Transit Act, authorized by the New York State Legislature in 1894.[5]:139–140 The subway plans were drawn up by a team of engineers led by William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer of the Rapid Transit Commission. It called for a subway line from New York City Hall in lower Manhattan to the Upper West Side, where two branches would lead north into the Bronx.[6]:3 A plan was formally adopted in 1897, and legal challenges were resolved near the end of 1899.[5]:148 The Rapid Transit Construction Company, organized by John B. McDonald and funded by August Belmont Jr., signed Contract 1 with the Rapid Transit Commission in February 1900,[7] in which it would construct the subway and maintain a 50-year operating lease from the opening of the line.[5]:182 In 1901, the firm of Heins & LaFarge was hired to design the underground stations.[6]:4 Belmont incorporated the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) in April 1902 to operate the subway.[5]:182

The 14th Street station was constructed as part of the IRT's original line, particularly the section from Great Jones Street to 41st Street. Construction on this section of the line began on September 12, 1900. The section from Great Jones Street to a point 100 feet (30 m) north of 33rd Street had been awarded to Holbrook, Cabot & Daly Contracting Company.[7] The 14th Street station opened on October 27, 1904, as one of the original 28 stations of the New York City Subway from City Hall to 145th Street on the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line.[5]:186[8] The opening of the 14th Street station turned Union Square into a major transportation hub.[9][10] With the northward relocation of the city's theater district, Union Square became a major wholesaling district with several loft buildings, as well as numerous office buildings.[11][12][4]:11

Initially, the IRT station was served by local and express trains along both the West Side (now the Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line to Van Cortlandt Park–242nd Street) and East Side (now the Lenox Avenue Line). West Side local trains had their southern terminus at City Hall during rush hours and South Ferry at other times, and had their northern terminus at 242nd Street. East Side local trains ran from City Hall to Lenox Avenue (145th Street). Express trains had their southern terminus at South Ferry or Atlantic Avenue and had their northern terminus at 242nd Street, Lenox Avenue (145th Street), or West Farms (180th Street).[13] Express trains to 145th Street were later eliminated, and West Farms express trains and rush-hour Broadway express trains operated through to Brooklyn.[14] In 1918, the Lexington Avenue Line opened north of Grand Central–42nd Street, thereby dividing the original line into an "H" system. All trains were sent via the Lexington Avenue Line.[15]

In 1909, to address overcrowding, the New York Public Service Commission proposed lengthening platforms at stations along the original IRT subway.[16]:168 On January 18, 1910, a modification was made to Contracts 1 and 2 to lengthen station platforms to accommodate ten-car express and six-car local trains. In addition to $1.5 million (equivalent to $41.2 million in 2019) spent on platform lengthening, $500,000 (equivalent to $13,719,643 in 2019) was spent on building additional entrances and exits. It was anticipated that these improvements would increase capacity by 25 percent.[17]:15 At the 14th Street station, the northbound island platform was extended 55 feet (17 m) north and 100 feet (30 m) south, while the southbound island platform was extended 128 feet (39 m) north, necessitating the replacement of some structural steel north of the intersection of Fourth Avenue and 13th Street.[17]:107–108 On January 23, 1911, ten-car express trains began running on the Lenox Avenue Line, and the following day, ten-car express trains were inaugurated on the West Side Line.[16]:168[18]

Dual Contracts

After the original IRT opened, the city began planning new lines. The New York Public Service Commission adopted plans for what was known as the Broadway–Lexington Avenue route (later the Broadway Line) on December 31, 1907.[5]:212 A proposed Tri-borough system was adopted in early 1908, incorporating the Broadway Line. Operation of the line was assigned to the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT, subsequently the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation or BMT) in the Dual Contracts, adopted on March 4, 1913.[5]:203–219[19] Because the Dual Contracts specified that the street surfaces needed to remain intact during the system's construction, a temporary web of timber supports was erected to support the streets overhead while the BMT platforms were being constructed.[4]:3 The Broadway Line platforms opened on September 4, 1917, as the northern terminus of the first section of the line between 14th Street and Canal Street. Initially, it only served local trains.[20][21] On January 5, 1918, the Broadway Line was extended north to Times Square–42nd Street and south to Rector Street, and express service started on the line.[22]

The Dual Contracts also called for the construction of a subway under 14th Street, to run to Canarsie in Brooklyn; this became the BMT's Canarsie Line. Booth and Flinn was awarded the contract to construct the line on January 13, 1916.[23] Clifford Milburn Holland served as the engineer-in-charge during the construction.[24] The Canarsie Line station at Union Square opened on June 30, 1924, as part of the 14th Street–Eastern Line, which ran from Sixth Avenue under the East River and through Williamsburg to Montrose and Bushwick Avenues.[25][26] A passageway between the Broadway and Canarsie Line stations was completed in late 1923.[27]

Later years

The transfer between the IRT and BMT was placed inside fare control on July 1, 1948.[1] In the 1960s, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) started a project to lengthen station platforms on the Broadway Line to 615 feet (187 m) to accommodate 10-car trains.[28] As part of the project, the Broadway Line platforms at Union Square, which were 535 feet (163 m) long, were extended 85 feet (26 m) to the north.[29] The Broadway Line station was overhauled in the late 1970s. The MTA replaced the original wall tiles, old signs, and incandescent lighting with the 1970s wall tile band and tablet mosaics, signs and fluorescent lights. They also fixed staircases and platform edges.

By 1982, the entrances in the southern portion of Union Square were to be renovated as part of a refurbishment of Union Square Park.[30] This work was performed over the latter half of that decade, with the entrances having been renovated by 1985.[31][32][33] In the late 1980s, the 14th Street–Union Square station was renovated as part of the construction of the Zeckendorf Towers immediately east of the Lexington Avenue Line platforms.[4]:4 The towers' developers agreed to build and maintain subway entrances within the Zeckendorf Towers as "a public benefit", and in exchange, were allowed to develop the site. This was because of zoning rules that required many developers in Lower Manhattan, Midtown Manhattan, and Downtown Brooklyn to relocate and maintain subway entrances that were formerly on the street.[34] The New York City Department of City Planning prepared zoning guidelines for the Union Square area, which would allow a greater maximum floor area ratio in exchange for subway improvements, particularly benefiting the Zeckendorf project.[35]

On August 28, 1991, an accident just north of the IRT station killed five riders and injured 215 others in one of the deadliest accidents in New York City Subway history. The operator of a southbound 4 train was to be shifted to the local track due to repair work on the express one. He was running at 40 mph (64 km/h) in a 10 mph (16 km/h) zone and took the switch so fast that only the first car made it through the crossover, and the rest of the train was derailed. Five cars were damaged heavily, being scrapped on site, and the track infrastructure suffered heavy structural damage as a result.[36] The entire infrastructure, including signals, switches, track, roadbed, cabling, and 23 support columns needed to be replaced.[37] The derailment occurred at the entry to a former pocket track on the Lexington Avenue Line station, which was removed when the damage from the 1991 wreck was repaired,[38][39]

In the 1990s, the station underwent a major renovation. On July 9, 1993, the contract for the project's design was awarded for $2,993,948. As part of the contract, the consultant investigated whether it was feasible to reconfigure the IRT passageway, to reframe the exit structure on the Lexington Avenue platforms to accommodate the relocation and widening of stairs, the construction of a new fan room, the removal of stairs on the Broadway Line platforms, the reframing of the existing structure, and the construction of a new staircase between the intermediate and IRT mezzanines. These were all deemed feasible, and in May 1994, a supplemental agreement worth $984,998 was reached to allow the consultant to prepare the design for this work.[40]:C-57 Plans were prepared by Lee Harris Pomeroy. The project was to cost $38.5 million and start in December 1994, with a new entrance pavilion on the southeast corner of Union Square Park, containing an elevator entrance.[41] The same year, a New York City Transit Police station opened in the Broadway Line mezzanine.[4]:4 A construction contract was ultimately signed in March 1995.[42] The work involved creating a pocket park in a traffic island at the southeast corner of Union Square, a project that was completed in 2000.[43] In addition, power infrastructure had to be upgraded to allow the construction of MetroCard vending machine equipment.[44] In 2002, the Broadway Line station was upgraded for ADA-accessibility and its original late 1910s tiling was restored. As part of the upgrade, the MTA repaired the staircases, re-tiled for the walls and floors, upgraded the station's lights and the public address system, installed yellow safety treads along the platform edge, new signs, and new trackbeds in both directions.

As part of the 2015–2019 MTA Capital Program and the L Project, several modifications were implemented on the platform to improve circulation and to reduce crowding. The stairs from the Broadway Line platforms were rebuilt in March 2019; the stair from the downtown Broadway Line platform was reconfigured entirely.[45][46] Additionally, a new escalator was installed from the east mezzanine to the platform; it cost around $15 million and opened on September 10, 2020.[47][48][49]

Station layout

| G | Street level | Exit/entrance |

| B1 | Mezzanine | Fare control, station agent |

| B2 | Side platform, not in service | |

| Northbound local | ← ← (No service: 18th Street) | |

| Island platform | ||

| Northbound express | ← ← | |

| Southbound express | | |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound local | | |

| Side platform, not in service | ||

| B2 | Northbound local | ← ← ← ← |

| Island platform | ||

| Northbound express | ← ← | |

| Southbound express | | |

| Island platform | ||

| Southbound local | | |

| B3 | Westbound | ← |

| Island platform | ||

| Eastbound | | |

The IRT Lexington Avenue Line and BMT Broadway Line stations run roughly parallel to each other in a north-south direction. The Lexington Avenue Line platforms run under Fourth Avenue and Union Square East, while the Broadway Line platforms to the west run under Broadway, cutting directly under Union Square Park. The BMT Canarsie Line station runs west-east under both of the other stations, along 14th Street.[4]:3

A 480-foot-long (150 m) mezzanine stretches above the BMT Broadway Line platforms, ramping down to a control area at its south end, where there are stairs down to the Broadway Line platforms and transfers to the other platforms. Along the mezzanine and adjacent passageways, the tops of the walls contain friezes made of raised geometric patterns on the rectangular tiles. White-on-green tiles with the number "14" are placed at the tops of the walls at regular intervals, while white-on-green "Union Square" tablets are installed below the friezes. Rectangular red metal frames also surround sections of the original wall. The mezzanine is relatively shallow, and because it was built with insufficient clearance, Union Square Park was raised by 4 feet (1.2 m) to accommodate the station.[4]:4, 6 Imprinted on the walls are over 3,000 stickers with the names of victims of the September 11 attacks, which were put up by artist John Lin and sixteen friends on September 10, 2002.[50] The stickers were not sanctioned by the subway system's operator, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and have deteriorated since they were placed.[51][52]

Directly east of the control area at the south end of the BMT Broadway Line mezzanine, a 20-foot-wide (6 m) corridor slopes down to the IRT mezzanine. The IRT mezzanine contains two overpasses, connecting the station complex with exits on the east side of both Fourth Avenue and Union Square East. Galleries extend from the overpasses above the platforms, with stairs leading downward from the galleries to each island platform. A corridor runs above the western side of the IRT station, connecting the two overpasses. This corridor contains restored cross-segments of the original station wall, including faience cornices, mosaic tile borders, and plaques of eagles.[4]:4–5 These are part of a larger, station-wide art installation entitled Framing Union Square, by Mary Miss.[53][54] Original faience plaques with the number "14" are in the southern end of the mezzanine, near one of the entrances. Other decorations, such as a pale blue frieze, date from later renovations. The area near the Zeckendorf Towers contains storefronts, as well as steel and glass enclosures.[4]:5

Another staircase extends from the IRT mezzanine to a small mezzanine above the Canarsie Line platform. Another mezzanine on the western side of the station serves the Canarsie Line platform directly. There were several connecting passageways between the western Canarsie Line mezzanine and the larger concourse area above the Broadway Line. However, these passageways have been sealed off. The passageways to the Canarsie Line platform contain cruciform borders similar to those in the other passageways.[4]:6–7, 18

Exits

The station contains numerous entrances and exits. Near the southeast end of the station, there is one stair, escalator bank, and elevator in the Zeckendorf Towers at the northeast corner of 4th Avenue and 14th Street; this is the ADA-accessible entrance to the station. There are two stairs to each of the southwest and southeast corners of the same intersection. All of these lead directly to the Lexington Avenue Line mezzanine. One block to the west, there are two staircases on the south side of 14th Street between Broadway and University Place, which lead to the western Canarsie Line mezzanine.[4]:18[55] Plans show that a closed exit extended to the west side of Broadway between 13th and 14th Streets.[4]:18

The central portion of the station contains another exit from the Lexington Avenue Line mezzanine to the Zeckendorf Towers, which leads to the southeast corner of Union Square East and 15th Street. There are also two stairs inside Union Square Park between 14th and 15th Streets. One is closer to Union Square West between these two streets, opposite the equestrian statue of George Washington, while the other is closer to Union Square East and 15th Street. These entrances more directly serve the Broadway Line platforms.[4]:18[55] The Union Square Park entrances contain large polygonal metal-and-glass canopies, which date from a 1985 renovation of the park.[4]:7[31]

At the northern end of the station, two stairs rise to Union Square Park on the east side of Union Square West at 16th Street. These lead most directly to the Broadway Line platforms.[55]

IRT Lexington Avenue Line platforms

14 Street–Union Square | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Downtown platform for the local services (left) and express services (right), showing the curvature of the station and the movable platforms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station statistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Division | A (IRT) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | IRT Lexington Avenue Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | 4 5 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 2 island platforms (in service) cross-platform interchange 2 side platforms (abandoned) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | October 27, 1904[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | 406[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessibility | Cross-platform wheelchair transfer available | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opposite- direction transfer | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station succession | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Next north | Grand Central–42nd Street (express): 4 23rd Street (local): 4 18th Street (local; closed): no service | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Next south | Astor Place (local): 4 Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall (express): 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

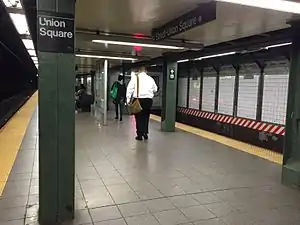

14th Street–Union Square is an express station on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line. The 4 and 6 trains stop here at all times;[56][57] the 5 train stops here at all times except late nights;[58] and the <6> train stops here during weekdays in the peak direction.[57] The station has four tracks and two island platforms. The uptown and downtown platforms are offset from each other, having been extended at their rear ends, and are slightly curved.[4]:5[59] Platform gap fillers, on the downtown side, use proximity sensors to detect when trains arrive, automatically extending when a train has stopped in the station.[4]:5

The island platforms allow for cross-platform interchanges between local and express trains heading in the same direction. Local trains use the outer tracks while express trains use the inner tracks.[59] The island platforms were originally 350 feet (110 m) long, as at other express stations on the original IRT,[6]:4[60]:8 but later became 525 feet (160 m) long. The platforms are 30 feet (9.1 m) wide at their widest point.[60]:8

The station has two abandoned local side platforms; the northbound platform is visible through windows, bordered with wide, bright red frames.[4]:5 A combination of island and side platforms was also used at Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line and 96th Street on the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line.[60]:8 These side platforms were built to accommodate extra passenger volume and were built to the five-car length of the original IRT local trains. When trains were lengthened, the side platforms were deemed obsolete, and they were closed and walled off.

Design

As with other stations built as part of the original IRT, the tunnel is covered by a "U"-shaped trough that contains utility pipes and wires. The bottom of this trough contains a foundation of concrete no less than 4 inches (100 mm) thick.[4]:3–4[60]:9 Each platform consists of 3-inch-thick (7.6 cm) concrete slabs, beneath which are drainage basins. The platforms contain I-beam columns spaced every 15 feet (4.6 m). Additional columns between the tracks, spaced every 5 feet (1.5 m), support the jack-arched concrete station roofs.[4]:3–4[6]:4[60]:9 There is a 1-inch (25 mm) gap between the trough wall and the platform walls, which are made of 4-inch (100 mm)-thick brick covered over by a tiled finish.[4]:3–4[60]:9

The walls near the tracks do not have any identifying motifs with the station's name, as all station identification signs are on the platforms. The trackside walls contain vertical white glass tiles.[4]:5 The original decorative scheme for the side platforms consisted of blue tile station-name tablets, blue and buff tile bands, a yellow faience cornice, and blue faience plaques. The decorative work was performed by faience contractor Grueby Faience Company.[60]:35

Track layout

Similar to 72nd Street on the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, this station was built with extra tracks on the approach to the station. These were between the local and express tracks and were approximately 300 feet (91 m) long. The idea was to have a "stacking" track where a train could be held momentarily until the platform cleared for it to enter the station. The tracks here and at 72nd Street were rendered useless when train lengths grew beyond these tracks' capacity.[59] The northern track was removed as a result of the 1991 derailment.[38] A similar track still exists between the northbound tracks south of the 14th Street–Union Square station's northbound platform.[59]

BMT Broadway Line platforms

14 Street–Union Square | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Division | B (BMT) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | BMT Broadway Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | N Q R W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 2 island platforms cross-platform interchange | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | September 4, 1917[21] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | 015[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessible | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opposite- direction transfer | Yes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station succession | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Next north | 34th Street–Herald Square (express): N 23rd Street (local): N | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Next south | Eighth Street–New York University (local): N Canal Street (express): N | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

14th Street–Union Square is an express station on the BMT Broadway Line that has four tracks and two island platforms. The N and Q trains stop here at all times.[61][62] The R stops here at all times except late nights,[63] while the W stops here during weekdays.[64] The island platforms were originally 535 feet (163 m) long, but as a result of an extension in the early 1970s, became 525 feet (160 m) long.[29][4]:5 The platforms are 30 feet (9.1 m) below the street. At the southern end of each platform, three stairs and an elevator lead to the mezzanine, and one stair leads to the Canarsie Line platforms. At the northern end of each platform, two stairs lead to the mezzanine. [4]:5–6, 18

The tunnel is covered by a "U"-shaped trough that contains utility pipes and wires. The bottom of this trough contains a concrete foundation no less than 4 inches (100 mm) thick. Each platform consists of 3-inch-thick (7.6 cm) concrete slabs, beneath which are drainage basins. The platforms contain I-beam columns spaced every 15 feet (4.6 m). Additional columns between the tracks, spaced every 5 feet (1.5 m), support the jack-arched concrete station roofs. The trackside walls also contain exposed I-beam columns, dividing the trackside walls into 5-foot-wide panels.[4]:3–4

The panels on the trackside walls consist of white square ceramic tiles. A frieze with multicolored geometric patterns runs atop the trackside walls, with a square mosaic tile placed inside the frieze at intervals of three panels. A band of narrow green tiles runs along the left and right edges of each white-tiled panel, as well as below the frieze and mosaic tiles.[4]:6 The mosaic tiles, by Jay Van Everen, are part of a work entitled "The junction of Broadway and Bowery Road, 1828", a reference to the two streets that intersected at Union Square.[4]:6[65] In 2005, an artwork called City Glow by Chiho Aoshima was installed here.[66][67]

BMT Canarsie Line platform

Union Square | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station statistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Division | B (BMT) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | BMT Canarsie Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 1 island platform | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | June 30, 1924 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | 117[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opposite- direction transfer | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former/other names | 14 Street–Union Square | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station succession | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Next west | Sixth Avenue: L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Next east | Third Avenue: L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Union Square (announced as 14th Street-Union Square on rolling stock) on the BMT Canarsie Line has two tracks and one island platform. The L train stops here at all times.[68] Various stairs and an elevator go up from the platform to the mezzanine. There are also two stairs leading directly to each of the Broadway Line platforms.[4]:7, 18 An escalator leads directly from the Canarsie Line platform to the IRT mezzanine.[49]

The tunnel is covered by a "U"-shaped trough that contains utility pipes and wires. The bottom of this trough contains a concrete foundation no less than 4 inches (100 mm) thick. The platform consists of 3-inch-thick (7.6 cm) concrete slabs, beneath which are drainage basins. The platform contains I-beam columns spaced every 15 feet (4.6 m). The trackside walls also contain exposed I-beam columns, dividing the trackside walls into 5-foot-wide panels.[4]:3–4

The panels on the trackside walls consist of white square ceramic tiles. A band of narrow green tiles runs along the left, right, and top edges of each white-tiled panel. A frieze with multicolored geometric patterns runs atop the trackside walls, with a hexagonal mosaic tile with the letter "U" placed inside the frieze at intervals of three panels.[4]:6–7

References

- "Transfer Points Under Higher Fare; Board of Transportation Lists Stations and Intersections for Combined Rides". The New York Times. June 30, 1948. p. 19. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Station Developers' Information". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- "Facts and Figures: Annual Subway Ridership 2014–2019". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "New York MPS 14th Street-Union Square Subway Station (IRT; Dual System BMT)". Records of the National Park Service, 1785–2006, Series: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013–2017, Box: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: New York, ID: 75313911. National Archives.

- Walker, James Blaine (1918). Fifty Years of Rapid Transit — 1864 to 1917. New York, N.Y.: Law Printing. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- "Interborough Rapid Transit System, Underground Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 23, 1979. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Report of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners for the City of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1904 Accompanied By Reports of the Chief Engineer and of the Auditor. Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. 1905. pp. 229–236.

- "Our Subway Open: 150,000 Try It; Mayor McClellan Runs the First Official Train". The New York Times. October 28, 1904. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Germania Life Insurance Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 6, 1988. p. 2. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- "Plans for Everett House Site Improvement" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 81 (2101): 1178. June 20, 1908 – via columbia.edu.

- "Tammany Hall" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 29, 2013. p. 2. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). "New York City Guide". New York: Random House. pp. 198–203. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- The Merchants' Association of New York Pocket Guide to New York. Merchants' Association of New York. March 1906. pp. 19–26.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle Almanac. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1916. p. 119.

- "Open New Subway Lines to Traffic; Called a Triumph — Great H System Put in Operation Marks an Era in Railroad Construction — No Hitch in the Plans — But Public Gropes Blindly to Find the Way in Maze of New Stations — Thousands Go Astray — Leaders in City's Life Hail Accomplishment of Great Task at Meeting at the Astor" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- Hood, Clifton (1978). "The Impact of the IRT in New York City" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 146–207 (PDF pp. 147–208). Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Report of the Public Service Commission for the First District of the State of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1910. Public Service Commission. 1911.

- "Ten-car Trains in Subway to-day; New Service Begins on Lenox Av. Line and Will Be Extended to Broadway To-morrow". The New York Times. January 23, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- Engineering News, A New Subway Line for New York City, Volume 63, No. 10, March 10, 1910

- "Broadway Subway Opened To Coney By Special Train. Brooklynites Try New Manhattan Link From Canal St. to Union Square. Go Via Fourth Ave. Tube". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 4, 1917. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- "Open First Section of Broadway Line; Train Carrying 1,000 Passengers Runs from Fourteenth Street to Coney Island". The New York Times. September 5, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- "Open New Subway To Times Square; Brooklyn Directly Connected with Wholesale and Shopping Districts of New York. Nickel Zone Is Extended. First Train in Broadway Tube Makes Run from Rector Street in 17 Minutes. Cost About $20,000,000 Rapid Transit from Downtown to Hotel and Theatre Sections Expected to Affect Surface Lines. Increases Five-Cent Zone. First Trip to Times Square. Benefits to Brooklyn" (PDF). The New York Times. January 6, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- "East River Tunnel Contract Awarded". The New York Times. January 14, 1916. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- Aronson, Michael (June 15, 1999). "The Digger Clifford Holland". Daily News. New York. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "Subway Tunnel Through – Passage Under East River in East 14th Street Line Complete" (PDF). The New York Times. August 8, 1919. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- "Celebrate Opening of Subway Link" (PDF). The New York Times. July 1, 1924. p. 23. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- New York (State). Transit Commission (1923). Proceedings of the Transit Commission, State of New York. pp. 1136–1137. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- New York City Transit Authority Annual Report For The Year June 30, 1960. New York City Transit Authority. 1960. pp. 16–17.

- Rogoff, Dave (February 1969). "BMT Broadway Subway Platform Extensions" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 12 (1): 4.

- Carmody, Deirdre (November 29, 1982). "Union Square Park to Undergo Overhaul". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Carmody, Deirdre (May 23, 1985). "Union Square Park Reopens With a Lush Grandeur". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Metropolis. Bellerophon Publications. 1986. p. 18. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Reynolds, D.M.; Reynolds, A. (1994). The Architecture of New York City: Histories and Views of Important Structures, Sites, and Symbols. Wiley. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-471-01439-3. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Satow, Julie (March 16, 2011). "Developers in New York Try to Ease Prickly Relations". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Daniels, Lee A. (April 6, 1984). "About Real Estate; the Efforts to Revitalize Neglected Union Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- McFadden, Robert D. (September 1, 1991). "Catastrophe Under Union Square; Crash on the Lexington IRT: Motorman's Run to Disaster". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Sims, Calvin (September 3, 1991). "Subway Line Back After Being Closed By Fatal Derailing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Meredith, Jack (2012). Project management : a managerial approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 115–117. ISBN 978-0-470-53302-4. OCLC 757668996.

- "Moving Forward: Accelerating the Transition to Communications-Based Train Control for New York City's Subways" (PDF). Regional Plan Association. May 2014. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- NYC Transit Committee Agenda May 1994. New York City Transit. May 16, 1994.

- Howe, Marvine (January 2, 1994). "Neighborhood Report: Union Square; Revamping an Old Subway Station". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- "Posting: $40 Million Construction Contract Is Signed; Colorful Renovation for Union Sq. Station". The New York Times. March 12, 1995. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Friedman, Andrew (December 3, 2000). "Neighborhood Report: New York Parks; in Union Square, the End of a Long Wait". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Hays, Constance L. (December 29, 1996). "Notes from the Underground: Station Renovations Continue. Watch Your Step on the Tiles". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- "Project Details – Circulation Improvements at Union Square on the Canarsie Line". web.mta.info. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "MTA Capital Program 2015–2019 Renew. Enhance. Expand. Amendment No. 2, as proposed to the MTA Board May 2017" (PDF). mta.info. May 24, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- "Circulation Improvements at Union Square on the Canarsie Line". web.mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 31, 2017. Archived from the original on February 19, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- Saltonstall, Gus (September 14, 2020). "New Escalator Opens At Union Square L Train Station: Photos". West Village, NY Patch. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Hallum, Mark (September 13, 2020). "New subway escalator in Union Square moves 92 people per minute, aims to reduce congestion". amNewYork. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Levine, Lester (April 23, 2019). "An Overlooked Memorial in Union Square Subway Station Commemorates 9/11 Victims". Untapped New York. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Pollak, Michael (September 24, 2011). "Answers to Questions About New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Brown, Nicole (September 6, 2018). "9/11 memorials in NYC: Where to honor victims of the terrorist attacks". amNewYork. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- "14th Street-Union Square – Mary Miss – Framing Union Square, 1998". web.mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Jacobs, Karrie (December 23, 1996). "Notes From Underground – Cityscape". New York Magazine. 29 (50): 34 – via Google Books.

- "MTA Neighborhood Maps: 14 St-Union Sq (N)(Q)(R)(W)". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- "4 Subway Timetable, Effective September 13, 2020". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- "6 Subway Timetable, Effective September 13, 2020". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- "5 Subway Timetable, Effective September 13, 2020". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- Dougherty, Peter (2020). Tracks of the New York City Subway 2020 (16th ed.). Dougherty. OCLC 1056711733.

- Framberger, David J. (1978). "Architectural Designs for New York's First Subway" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 1-46 (PDF pp. 367-412). Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "N Subway Timetable, Effective November 8, 2020" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- "Q Subway Timetable, Effective November 8, 2020" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- "R Subway Timetable, Effective November 8, 2020" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- "W Subway Timetable, Effective November 8, 2020" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- Schneider, Daniel B. (December 21, 1997). "F.Y.I. - Frieze Frame". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Chiho Aoshima – Rebirth of the World – SAM – Seattle Art Museum". www.seattleartmuseum.org. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Van Den Abeele, L.; Vanhaerents, W.; de Coninck, F. (2010). Disorder in the House: Vanhaerents Art Collection. Lanoo. p. 23. ISBN 978-90-209-9105-5. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- "L Subway Timetable, Effective November 8, 2020" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

Further reading

External links

Media related to 14th Street – Union Square (New York City Subway) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 14th Street – Union Square (New York City Subway) at Wikimedia Commons

nycsubway.org:

- nycsubway.org – IRT East Side Line: 14th Street/Union Square

- nycsubway.org – BMT Broadway Subway: 14th Street/Union Square

- nycsubway.org – BMT Canarsie Line: Union Square

- nycsubway.org – Framing Union Square Artwork by Mary Miss (1998)

- nycsubway.org – Paradise Artwork by Chiho Aoshima (2005)

- nycsubway.org – City Glow Artwork by Chiho Aoshima (2005)

Google Maps Street View:

- 14th Street and Broadway entrance to Canarsie Line

- 14th Street and Fourth Avenue entrance

- Entrance by Union Square East

- Union Square East and 15th Street entrance

- Entrance in Union Square Park

- Union Square West and 16th Street entrance

- Broadway Line platforms

- Canarsie Line platform

- IRT uptown platform

- Mezzanine

Other websites:

- Station Reporter – 14th Street–Union Square Complex

- Forgotten NY – Original 28 – NYC's First 28 Subway Stations

- MTA's Arts For Transit – 14th Street–Union Square

- Abandoned Stations – Abandoned Stations – 14th Street side platforms