Demographics of Uzbekistan

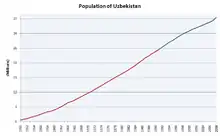

The demographics of Uzbekistan are the demographic features of the population of Uzbekistan, including population growth, population density, ethnicity, education level, health, economic status, religious affiliations, and other aspects of the population. The nationality of any person from Uzbekistan is Uzbek, while the ethnic Uzbek majority call themselves Uzbeks. Much of the data is estimated because the last census was carried out in Soviet times in 1989.

Demographic trends

Uzbekistan is Central Asia's most populous country. Its 32.5 million people (2018 estimate)[1][2] comprise nearly half the region's total population.

The population of Uzbekistan is very young: 34.1% of its people are younger than 14. According to official sources, Uzbeks comprise a majority (80%) of the total population. Other ethnic groups include Russians 5.5%, Tajiks 5%, Kazakhs 3%, Karakalpaks 2.5%, and Tatars 1.5% (1996 estimates).[3] Uzbekistan has an ethnic Korean population that was forcibly relocated to the region from the Soviet Far East in 1937-1938. There are also small groups of Armenians in Uzbekistan, mostly in Tashkent and Samarkand. The nation is 88% Muslim (mostly Sunni, with a 5% Shi'a minority), 9% Eastern Orthodox and 3% other faiths (which include small communities of Korean Christians, other Christian denominations, Buddhists, Baha'is, and more).[4] The Bukharan Jews have lived in Central Asia, mostly in Uzbekistan, for thousands of years. There were 94,900 Jews in Uzbekistan in 1989[5] (about 0.5% of the population according to the 1989 census), but now, since the collapse of the USSR, most Central Asian Jews left the region for the United States or Israel. Fewer than 5,000 Jews remain in Uzbekistan.[6]

Much of Uzbekistan's population was engaged in cotton farming in large-scale collective farms when the country was part of the Soviet Union. The population continues to be heavily rural and dependent on farming for its livelihood, although the farm structure in Uzbekistan has largely shifted from collective to individual since 1990.

Vital statistics

UN estimates

| Period | Births per year | Deaths per year | Natural change per year | CBR1 | CDR1 | NC1 | TFR1 | IMR1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1995 | 32.7 | 7.5 | 25.2 | 3.95 | ||||

| 1995–2000 | 25.6 | 6.9 | 18.7 | 3.10 | ||||

| 2000–2005 | 21.3 | 6.4 | 14.9 | 2.51 | ||||

| 2005–2010 | 22.4 | 6.2 | 16.2 | 2.49 | ||||

| 2010–2015 | 22.9 | 6.2 | 16.7 | 2.43 | ||||

| 2015–2020 | 21.8 | 5.8 | 16.0 | 2.43 | ||||

| 2020–2025 | 18.6 | 5.9 | 12.7 | 2.31 | ||||

| 2025–2030 | 16.4 | 6.3 | 10.1 | 2.21 | ||||

| 2030–2035 | 15.7 | 6.9 | 8.8 | 2.12 | ||||

| 2035–2040 | 15.6 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 2.05 |

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs website > World Population Prospects: The 2019 revision.[7]

Births and deaths

| Average population | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 6,314,000 | 192,188 | 54,612 | 137,576 | 30.4 | 8.6 | 21.8 | |

| 1951 | 6,511,000 | 207,302 | 49,275 | 158,027 | 31.8 | 7.6 | 24.3 | |

| 1952 | 6,704,000 | 223,452 | 55,068 | 168,384 | 33.3 | 8.2 | 25.1 | |

| 1953 | 6,909,000 | 219,832 | 60,855 | 158,977 | 31.8 | 8.8 | 23.0 | |

| 1954 | 7,085,000 | 237,470 | 58,345 | 179,125 | 33.5 | 8.2 | 25.3 | |

| 1955 | 7,256,000 | 248,545 | 59,370 | 189,175 | 34.3 | 8.2 | 26.1 | |

| 1956 | 7,466,000 | 267,187 | 46,210 | 220,977 | 35.8 | 6.2 | 29.6 | |

| 1957 | 7,720,000 | 276,668 | 47,568 | 229,100 | 35.8 | 6.2 | 29.7 | |

| 1958 | 7,979,000 | 300,646 | 48,433 | 252,213 | 37.7 | 6.1 | 31.6 | |

| 1959 | 8,252,000 | 305,082 | 50,254 | 254,828 | 37.0 | 6.1 | 30.9 | |

| 1960 | 8,558,000 | 340,618 | 51,758 | 288,860 | 39.8 | 6.0 | 33.8 | |

| 1961 | 8,895,000 | 339,952 | 53,591 | 286,361 | 38.2 | 6.0 | 32.2 | |

| 1962 | 9,237,000 | 341,352 | 56,178 | 285,174 | 37.0 | 6.1 | 30.9 | |

| 1963 | 9,574,000 | 342,659 | 54,502 | 288,157 | 35.8 | 5.7 | 30.1 | |

| 1964 | 9,905,000 | 346,847 | 53,315 | 293,532 | 35.0 | 5.4 | 29.6 | |

| 1965 | 10,233,000 | 355,135 | 60,056 | 295,079 | 34.7 | 5.9 | 28.8 | |

| 1966 | 10,557,000 | 360,336 | 60,115 | 300,221 | 34.1 | 5.7 | 28.4 | |

| 1967 | 10,886,000 | 359,623 | 64,627 | 294,996 | 33.0 | 5.9 | 27.1 | |

| 1968 | 11,259,000 | 385,687 | 64,762 | 320,925 | 34.3 | 5.8 | 28.5 | |

| 1969 | 11,625,000 | 380,729 | 69,147 | 311,582 | 32.8 | 6.0 | 26.8 | |

| 1970 | 11,973,000 | 401,613 | 66,189 | 335,424 | 33.6 | 5.5 | 28.1 | |

| 1971 | 12,354,000 | 425,646 | 67,162 | 358,484 | 34.4 | 5.4 | 29.0 | |

| 1972 | 12,756,000 | 421,458 | 77,942 | 343,516 | 33.0 | 6.1 | 26.9 | |

| 1973 | 13,155,000 | 441,237 | 83,170 | 358,067 | 33.5 | 6.3 | 27.2 | |

| 1974 | 13,569,000 | 462,062 | 86,864 | 375,198 | 34.1 | 6.4 | 27.7 | |

| 1975 | 13,981,000 | 478,604 | 100,213 | 378,391 | 34.2 | 7.2 | 27.0 | |

| 1976 | 14,389,000 | 503,514 | 101,544 | 401,970 | 35.0 | 7.1 | 27.9 | |

| 1977 | 14,786,000 | 493,329 | 104,297 | 389,032 | 33.4 | 7.1 | 26.3 | |

| 1978 | 15,184,000 | 514,030 | 105,204 | 408,826 | 33.9 | 6.9 | 27.0 | |

| 1979 | 15,578,000 | 535,928 | 109,459 | 426,469 | 34.4 | 7.0 | 27.4 | |

| 1980 | 15,952,000 | 540,047 | 118,886 | 421,161 | 33.9 | 7.5 | 26.4 | |

| 1981 | 16,376,000 | 572,197 | 117,793 | 454,404 | 34.9 | 7.2 | 27.7 | |

| 1982 | 16,813,000 | 589,283 | 124,137 | 465,146 | 35.0 | 7.4 | 27.7 | |

| 1983 | 17,261,000 | 609,400 | 128,779 | 480,621 | 35.3 | 7.5 | 27.8 | |

| 1984 | 17,716,000 | 641,398 | 132,042 | 509,356 | 36.2 | 7.5 | 28.8 | |

| 1985 | 18,174,000 | 679,057 | 131,686 | 547,371 | 37.4 | 7.2 | 30.1 | |

| 1986 | 18,634,000 | 708,658 | 132,213 | 576,445 | 38.0 | 7.1 | 30.9 | |

| 1987 | 19,095,000 | 714,454 | 133,781 | 580,673 | 37.4 | 7.0 | 30.4 | |

| 1988 | 19,561,000 | 694,144 | 134,688 | 559,456 | 35.5 | 6.9 | 28.6 | |

| 1989 | 20,108,000 | 668,807 | 126,862 | 541,945 | 33.3 | 6.3 | 27.0 | |

| 1990 | 20,465,000 | 691,636 | 124,553 | 567,083 | 33.8 | 6.1 | 27.7 | 4.20 |

| 1991 | 20,857,000 | 723,420 | 130,294 | 593,126 | 34.7 | 6.2 | 28.4 | |

| 1992 | 21,354,000 | 680,459 | 140,092 | 540,367 | 31.9 | 6.6 | 25.3 | |

| 1993 | 21,847,000 | 692,324 | 145,294 | 547,030 | 31.7 | 6.7 | 25.0 | |

| 1994 | 22,277,000 | 657,725 | 148,423 | 509,302 | 29.5 | 6.7 | 22.9 | |

| 1995 | 22,684,000 | 677,999 | 145,439 | 532,560 | 29.9 | 6.4 | 23.5 | 3.60 |

| 1996 | 23,128,000 | 634,842 | 144,829 | 490,013 | 27.4 | 6.3 | 21.2 | |

| 1997 | 23,560,000 | 602,694 | 137,331 | 465,363 | 25.6 | 5.8 | 19.8 | |

| 1998 | 23,954,000 | 553,745 | 140,526 | 413,219 | 23.1 | 5.9 | 17.3 | |

| 1999 | 24,312,000 | 544,788 | 130,529 | 414,259 | 22.4 | 5.4 | 17.0 | |

| 2000 | 24,650,000 | 527,580 | 135,598 | 391,982 | 21.4 | 5.5 | 15.9 | 2.59 |

| 2001 | 24,965,000 | 512,950 | 132,542 | 380,408 | 20.5 | 5.3 | 15.2 | |

| 2002 | 25,272,000 | 532,511 | 137,028 | 395,483 | 21.1 | 5.4 | 15.6 | |

| 2003 | 25,568,000 | 508,457 | 135,933 | 372,524 | 19.9 | 5.3 | 14.6 | |

| 2004 | 25,864,000 | 540,381 | 130,357 | 410,024 | 20.9 | 5.0 | 15.9 | |

| 2005 | 26,167,000 | 533,530 | 140,585 | 392,945 | 20.4 | 5.4 | 15.0 | 2.36 |

| 2006 | 26,488,000 | 555,946 | 139,622 | 416,324 | 21.0 | 5.3 | 15.7 | |

| 2007 | 26,868,000 | 608,917 | 137,430 | 471,487 | 22.7 | 5.1 | 17.5 | |

| 2008 | 27,303,000 | 646,096 | 138,792 | 507,304 | 23.7 | 5.1 | 18.6 | |

| 2009 | 27,767,000 | 649,727 | 130,659 | 519,068 | 23.4 | 4.7 | 18.7 | |

| 2010 | 28,562,000 | 634,810 | 138,411 | 496,399 | 22.2 | 4.8 | 17.4 | 2.34 |

| 2011 | 29,339,000 | 626,881 | 144,585 | 482,296 | 21.4 | 4.9 | 16.4 | 2.24 |

| 2012 | 29,774,000 | 625,106 | 145,988 | 479,118 | 21.0 | 4.9 | 16.1 | 2.19 |

| 2013 | 30,243,000 | 679,519 | 145,672 | 533,847 | 22.5 | 4.8 | 17.7 | 2.35 |

| 2014 | 30,759,000 | 718,036 | 149,761 | 568,998 | 23.3 | 4.9 | 18.4 | 2.46 |

| 2015 | 31,576,000 | 734,141 | 152,035 | 582,106 | 23.5 | 4.9 | 18.6 | |

| 2016 | 32,121,000 | 726,170 | 154,791 | 571,379 | 22.8 | 4.8 | 18.0 | 2.46 |

| 2017 | 32,653,000 | 715,519 | 160,723 | 554,796 | 22.1 | 5.0 | 17.1 | |

| 2018 | 33,254,000 | 768,520 | 154,913 | 613,607 | 23.3 | 4.7 | 18.6 | |

| 2019 | 33,905,000 | 815,939 | 154,959 | 660,980 | 24.3 | 4.6 | 19.7 | |

| 2020 | 34,558,900 | 841,800 | 175,600 | 666,200 | 24.6 | 5.1 | 19.5 |

Current vital statistics

Births:

- January–June 2019: 347,300 (21.0)

- January–June 2020:

365,200 (21.6)

365,200 (21.6)

Deaths:

- January–June 2019: 74,200 (4.5)

- January–June 2020: 74,600 (4.4)

Natural increase:

- January–June 2019: 273,100 (16.5)

- January–June 2020:

290,600 (17.2)

290,600 (17.2)

Fertility and births

Total fertility rate (TFR) and crude birth rate (CBR):[17]

| Year | CBR (total) | TFR (total) | CBR (urban) | TFR (urban) | CBR (rural) | TFR (rural) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 27 | 3,34 (3,1) | 23 | 2,71 (2,5) | 29 | 3,74 (3,4) |

| 2002 | 24,4 | 2,92 | 19,8 | 2,48 | 27,5 | 3,21 |

Total fertility rate (TFR)

According to the CIA World Factbook, the total fertility rate (TFR) estimated as of 2011 is 1.89 children born/woman.[3][18][19]

In 2002, the estimated TFR was 2.92; Uzbeks 2.99, Russians 1.35, Karakalpak 2.69, Tajik 3.19, Kazakh 2.95, Tatar 2.05, others 2.53; Tashkent City 1.96, Karakalpakstan 2.90, Fergana 2.73; Eastern region 2.71, East Central 2.96, Central 3.43, Western 3.05.[20]

The high fertility rate during the Soviet Union and during its period of disintegration is partly due to the historical cultural preferences for large families, economic reliance upon agriculture, and the greater relative worth of Soviet child benefits in Uzbekistan.[21] Abortion was the preferred method of birth control. Legalized in 1955, the number of abortions increased by 231% from 1956-1973.[22] By 1991, the abortion ratio was 39 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age per year.[23]

However, in the past few decades, fertility control methods have shifted considerably from abortion to modern contraceptive methods, especially IUDs. By the mid-1980s IUDS became the main method of contraception through government and organizational policies that aimed to introduce women to modern contraceptives. According to a UHES report from 2002, 73% of married Uzbek woman had used the IUD, 14% male condom, and 13% the pill.[24]

The government supported the use of modern contraceptives to control fertility rates because of national economic difficulties that followed the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Thus the government has been influential in determining the popularity of the IUD. Despite family planning programs that educate women on different methods of contraception, the IUD has remained women’s first choice of contraception. Word of mouth and social relations also account for the strong preference for the IUD. Nevertheless, factors such as class and level of education have been shown to give women more freedom in their choice of contraception methods.

Regional differences

The regions of Surxondaryo and Qashqadaryo have the highest birth rate and the lowest death rates in Uzbekistan. On the other hand, the city of Tashkent has the lowest birth rate and the highest death rate of the country.

| Vital statistics by regions of the Republic of Uzbekistan [25] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Birth rate (‰) | Death rate (‰) | Natural growth rate (‰) | |||||||||||||||

| Surxondaryo Region | 26.8 | 4.2 | +22.6 | |||||||||||||||

| Qashqadaryo Region | 25.8 | 4.1 | +21.7 | |||||||||||||||

| Jizzakh Region | 25.2 | 4.2 | +21.0 | |||||||||||||||

| Samarqand Region | 26.2 | 4.3 | +21.9 | |||||||||||||||

| Namangan Region | 24.4 | 4.5 | +19.9 | |||||||||||||||

| Andijan Region | 23.8 | 5.1 | +18.7 | |||||||||||||||

| Navoiy Region | 22.3 | 4.3 | +18.0 | |||||||||||||||

| Xorazm Region | 22.0 | 4.5 | +17.5 | |||||||||||||||

| Fergana Region | 22.2 | 4.6 | +17.6 | |||||||||||||||

| Karakalpakstan | 21.6 | 4.6 | +17.0 | |||||||||||||||

| Sirdaryo Region | 22.3 | 4.6 | +17.7 | |||||||||||||||

| Bukhara Region | 21.3 | 4.2 | +17.1 | |||||||||||||||

| Tashkent Region | 20.6 | 5.7 | +14.9 | |||||||||||||||

| Tashkent | 18.6 | 6.3 | +12.3 | |||||||||||||||

Life expectancy

| Period | Life expectancy in Years |

Period | Life expectancy in Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 56.1 | 1985–1990 | 66.6 |

| 1955–1960 | 57.9 | 1990–1995 | 66.3 |

| 1960–1965 | 59.8 | 1995–2000 | 66.7 |

| 1965–1970 | 61.6 | 2000–2005 | 67.7 |

| 1970–1975 | 63.0 | 2005–2010 | 69.1 |

| 1975–1980 | 64.0 | 2010–2015 | 70.8 |

| 1980–1985 | 65.3 |

Source: UN World Population Prospects 2017[26]

Ethnic groups

Ethnic composition according to the 1989 population census (latest available):[18][19][27][28]

Uzbek 71%, Russian 6%, Khowar 2%, Tajik 5% (believed to be much higher[29][30][31]), Kazakh 4%, Tatar 3%, Karakalpak 2%, other 7%.

Estimates of ethnic composition in 1996 from CIA World Factbook:[32]

Uzbek 80%, Russian 5.5%, Tajik 5%, Kazakh 3%, Karakalpak 2.5%, Tatar 1.5%, other 2.5% (1996 est.)

The table shows the ethnic composition of Uzbekistan's population (in percent) according to four population censuses between 1926 and 1989 (no population census was carried out in 1999, and the next census is now being planned for 2010).[33] The increase in the percentage of Tajik from 3.9% of the population in 1979 to 4.7% in 1989 may be attributed, at least in part, to the change in census instructions: in the 1989 census for the first the nationality could be reported not according to the passport, but freely self-declared on the basis of the respondent's ethnic self-identification.[34]

| Ethnic group |

census 19261 | census 19392 | census 19593 | census 19704 | census 19795 | census 19896 | statistics 20177 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Uzbeks | 3,467,226 | 73.0 | 4,804,096 | 65.1 | 5,038,273 | 62.2 | 7,733,541 | 64.7 | 10,569,007 | 68.7 | 14,142,475 | 71.4 | 26,917,700 | 83.7 |

| Tajiks | 350,670 | 7.4 | 317,560 | 5.1 | 311,375 | 3.8 | 457,356 | 3.8 | 594,627 | 3.9 | 933,560 | 4.7 | 1,544,700 | 4.8 |

| Kazakhs | 191,126 | 4.0 | 305,416 | 4.9 | 335,267 | 4.1 | 549,312 | 4.6 | 620,136 | 4.0 | 808,227 | 4.1 | 803,400 | 2.5 |

| Russians | 245,807 | 5.2 | 727,331 | 11.6 | 1,090,728 | 13.5 | 1,495,556 | 12.5 | 1,665,658 | 10.8 | 1,653,478 | 8.4 | 750,000 | 2.3 |

| Karakalpaks | 142,688 | 3.0 | 181,420 | 2.9 | 168,274 | 2.1 | 230,273 | 1.9 | 297,788 | 1.9 | 411,878 | 2.1 | 708,800 | 2.2 |

| Kyrgyz | 79,610 | 1.7 | 89,044 | 1.4 | 92,725 | 1.1 | 110,864 | 1.0 | 142,182 | 0.7 | 174,907 | 0.8 | 274,400 | 0.9 |

| Tatars | 28,335 | 0.6 | 147,157 | 2.3 | 397,981 | 4.9 | 442,331 | 3.7 | 531,205 | 3.5 | 467,829 | 2.4 | 195,000 | 0.6 |

| Turkmens | 31,492 | 0.7 | 46,543 | 0.7 | 54,804 | 0.7 | 71,066 | 0.6 | 92,285 | 0.6 | 121,578 | 0.6 | 192,000 | 0.6 |

| Koreans | 30 | 0.0 | 72,944 | 1.2 | 138,453 | 1.7 | 151,058 | 1.3 | 163,062 | 1.1 | 183,140 | 0.9 | 176,900 | 0.6 |

| Ukrainians | 25,335 | 0.5 | 70,577 | 1.1 | 87,927 | 1.1 | 114,979 | 1.0 | 113,826 | 0.7 | 153,197 | 0.8 | 70,700 | 0.2 |

| Crimean Tatars | 46,829 | 0.6 | 135,426 | 1.1 | 117,559 | 0.8 | 188,772 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Turks | 371 | 0.0 | 474 | 0.0 | 21,269 | 0.3 | 46,398 | 0.4 | 48,726 | 0.3 | 106,302 | 0.5 | ||

| Jews | 37,621 | 0.8 | 50,676 | 0.8 | 94,303 | 1.2 | 102,843 | 0.9 | 99,836 | 0.7 | 94,689 | 0.5 | ||

| Armenians | 14,862 | 0.3 | 20,394 | 0.3 | 27,370 | 0.3 | 34,470 | 0.3 | 42,374 | 0.3 | 50,537 | 0.3 | ||

| Azerbaijanis | 20,764 | 0.4 | 3,645 | 0.1 | 40,511 | 0.5 | 40,431 | 0.3 | 59,779 | 0.4 | 44,410 | 0.2 | ||

| Uyghurs | 36,349 | 0.8 | 50,638 | 0.8 | 19,377 | 0.2 | 24,039 | 0.2 | 29,104 | 0.2 | 35,762 | 0.2 | ||

| Bashkirs | 624 | 0.0 | 7,516 | 0.1 | 13,500 | 0.2 | 21,069 | 0.2 | 25,879 | 0.2 | 34,771 | 0.2 | ||

| Others | 77,889 | 1.6 | 98,838 | 1.6 | 126,738 | 1.6 | 198,570 | 1.7 | 176,274 | 1.1 | 204,565 | 1.0 | 486,900 | 1.5 |

| Total | 4,750,175 | 6,271,269 | 8,105,704 | 11,959,582 | 15,389,307 | 19,810,077 | 32,120,500 | |||||||

| 1 Excluding the Tadzjik ASSR, but including the Kara-Kalpak Autonomous Oblast (in 1926 part of the Kazakh ASSR); source: . 2 Source: . 3 Source: . 4 Source: . 5 Source: . 6 Source: . 7 Source: | ||||||||||||||

Languages

According to the CIA factbook, the current language distribution is: Uzbek 74.3%, Russian 14.2%, Tajik 4.4% and Other 7.1.[32] The Latin script replaced Cyrillic in the mid-1990s. Following independence, Uzbek was made the official state language. President Islam Karimov, the radical nationalist group Birlik (Unity), and the Uzbek Popular Front promoted this change. These parties believed that Uzbek would stimulate nationalism and the change itself was part of the process of de-Russification, which was meant to deprive Russian language and culture of any recognition. Birlik held campaigns in the late 1980s to achieve this goal, with one event in 1989 culminating in 12,000 people in Tashkent calling for official recognition of Uzbek as the state language.[35] In 1995, the government adopted the Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on State Language, which mandates that Uzbek be used in all public spheres and official jobs. Scholars studying migration and ethnic minorities have since criticized the law as a source of discrimination toward minorities who do not speak Uzbek. Nevertheless, Russian remains the de facto language when it comes to science, inter-ethnic communication, business, and advertising.[36] According to unverifiable reports, Some people purport that the Persian-speaking Tajik population of Uzbekistan may be as large as 25%-30% of the total population,[37] but these estimates are based on unverifiable reports of "Tajiks around the country".[38]

Religions

Muslims constitute 88% of the population according to a 2013 US State Department release.[39] Approximately 10% of the population are Russian Orthodox Christians.[39]

There were 94,900 Jews in Uzbekistan in 1989[5] (about 0.5% of the population according to the 1989 census), but fewer than 5,000 remained in 2007.[6]

A study showed that 35% of surveyed consider religion as "very important".[40]

CIA World Factbook demographic statistics

- For the latest statistics, see this country's entry in the CIA World Factbook

The following demographic statistics are from the CIA World Factbook as of September 2009, unless otherwise indicated.

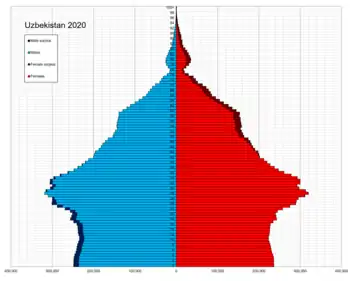

Age structure

0–14 years: 26% (male 3,970,386/female 3,787,371)

15–64 years: 67% (male 9,191,439/female 9,309,791)

65 years and over: 6% (male 576,191/female 770,829) (2009 est.)

Sex ratio

at birth: 1.06 male(s)/female

under 12 years 1.05 male(s)/female

15–64 years: 0.99 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.75 male(s)/female

total population: 0.99 male(s)/female (2009 est.)

Infant mortality rate

Total: 23.43 deaths/1,000 live births

Male: 27.7 deaths/1,000 live births

Female: 18.9 deaths/1,000 live births (2009 est.)

Life expectancy at birth

total population: 71.96 years

male: 68.95 years

female: 75.15 years (2009 est.)

Literacy

definition: age 15 and over can read and write

total population: 99.3%

male: 99.6%

female: 99% (2003 est.)

Education

The educational system has achieved 99% literacy, and the mean amount of schooling for both men and women is 12 years. The government provides free and compulsory 12-year education.

In 2016 Uzbekistan has acknowledged the country's lack of higher education services to support its market needs. In addition, private higher education providers have begun to emerge on the market to provide students with the necessary skills, knowledge and skills needed on the labor market. TEAM University, one of the private universities in Tashkent, aims to develop the skills required to start entrepreneurial activities, thereby contributing to the development of businesses and private enterprises.

Migration

As of 2011, Uzbekistan has a net migration rate of -2.74 migrant(s)/ 1000 population.[3]

The process of migration changed after the fall of the Soviet Union. During the Soviet Union, passports facilitated movement throughout the fifteen republics and movement throughout the republics was relatively less expensive than it is today.[41] An application for a labor abroad permit from a special department of the Uzbek Agency of External Labor Migration in Uzbekistan is required since 2003. The permit was originally not affordable to many Uzbeks and the process was criticized for the bureaucratic red tape it required. The same departments and agencies involved in creating this permit are consequently working to substantially reduce the costs as well as simplifying the procedure. On July 4, 2007, the Russian First Deputy Prime Minister Sergey Ivanov signed three agreements that would address labor activity and protection of the rights of the working migrants (this includes Russian citizens in Uzbekistan and Uzbek citizens in Russia) as well as cooperation in fighting undocumented immigration and the deportation of undocumented workers.[42]

Uzbek Migration

Economic difficulties have increased labor migration to Russia, Kazakhstan, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Turkey, the Republic of Korea, and Europe over the past decade.[43] At least 10% of Uzbekistan’s labor force works abroad.[44] Approximately 58% of the labor force that migrates, migrates to Russia.[42] High unemployment rates and low wages are responsible for labor migration.

Migrants typically are people from the village, farmers, blue-collar workers, and students who are seeking work abroad. However, many migrants are not aware of the legal procedures required to leave the country, causing many to end up unregistered in Uzbekistan or the host country. Without proper registration, undocumented migrants are susceptible to underpayment, no social guarantees and bad treatment by employers. According to data from the Russian Federal Immigration Service, there were 102,658 officially registered labor migrants versus 1.5 million unregistered immigrants from Uzbekistan in Russia in 2006. The total remittances for both groups combined was approximately US $1.3 billion that same year, eight percent of Uzbekistan’s GDP.[42]

Minorities

A significant number of ethnic and national minorities left Uzbekistan after the country became independent, but actual numbers are unknown. The primary reasons for migration by minorities include: few economic opportunities, a low standard of living, and a poor prospect for educational opportunities for future generations. Although Uzbekistan's language law has been cited as a source of discrimination toward those who do not speak Uzbek, this law has intertwined with social, economic, and political factors that have led to migration as a solution to a lack of opportunities in Uzbekistan.

Russians, who constituted a primarily urban population made up half of the population of Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, until the 1980s. Since then, the population has been gradually diminishing as many Russians have migrated to Russia. Nevertheless, Russian registration permits (propiska) constrain migration.[45] The decision to migrate is complicated by the fact that many Russians or other minority groups who have a “homeland” may view Uzbekistan as the “motherland.” It is also complicated by the fact that these groups might not speak the national language of their “homeland” or may be registered under another nationality on their passports. Nonetheless, “native” embassies facilitate this migration. Approximately 200 visas are given out to Jews from the Israel embassy weekly.[46]

See also

- Demography of Central Asia

References

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Uzbekistan in CIA World Factbook

- International Religious Freedom Report for 2004, U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (released 2004-09-15)

- World Jewish Population 2001, American Jewish Yearbook, vol. 101 (2001), p. 561.

- World Jewish Population 2007, American Jewish Yearbook, vol. 107 (2007), p. 592.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs website > World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision Archived May 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- United nations. Demographic Yearbooks

- "The State Statistics Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan". Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Естественное движение населения республик СССР, 1935 [Natural population growth of the Republics of the USSR, 1935] (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- }}

- "The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics". The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics. Archived from the original on 2019-08-02. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-28. Retrieved 2014-07-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Spoorenberg, Thomas (2013). "Fertility changes in Central Asia since 1980". Asian Population Studies. 9 (1): 50–77. doi:10.1080/17441730.2012.752238.

- Spoorenberg, Thomas (2015). "Explaining recent fertility increase in Central Asia". Asian Population Studies. 11 (2): 115–133. doi:10.1080/17441730.2015.1027275.

- A.I. Kamilov, J. Sullivan, and Z. D. Mutalova, Fertility Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, Chapter 4 in Uzbekistan Health Examination Survey 2002.

- Cynthia Buckley, “Challenges to Integrating Sexual Health Issues into Reproductive Health Programs in Uzbekistan,” Studies in Family Planning 37(3) (Sep. 2006), 157.

- Magali Barbieri, Elena Dolkigh, and Amon Ergashev. “Nuptiality, Fertility, Use of Contraception, and Family Planning in Uzbekistan,” Population Studies: A Journal of Demography (1996) 50: 1, 69-88.

- Cynthia Buckley, Jennifer Barrett, and Yakov P. Asminkin, “Reproductive and Sexual Health Among Young Adults in Uzbekistan” Studies In Family Planning (Mar. 2004), 4.

- Jennifer Barrett and Cynthia Buckley, “Constrained Contraceptive Choice: IUD Prevalence in Uzbekistan,” International Family Planning Perspectives (Jun. 2007), 52.

- "World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations". Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- Library of Congress, A Country Study: Uzbekistan. Ethnic composition

- A Country Study: Uzbekistan. Ethnic composition, Appendix Table 4.

- "Uzbekistan". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 1999. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2000-02-23. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- Svante E. Cornell (2000), "Uzbekistan: A Regional Player in Eurasian Geopolitics?", European Security, 9 (2): 115–140, doi:10.1080/09662830008407454

- Richard Foltz, "The Tajiks of Uzbekistan", Central Asian Survey, 15(2), 213-216 (1996).

- "Central Asia :: UZBEKISTAN". CIA The World Factbook.

- "Results of population censuses in Uzbekistan in 1959, 1970, 1979, and 1989". Archived from the original on 2008-06-20. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan Archived 2008-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Part 1: Ethnic minorities, Open Society Institute, p. 195 (in Russian).

- Nancy Lubin. “Uzbekistan: The Challenges Ahead,” Middle East Journal vol. 43, Number 4, Autumn 1989, 619-634.

- Radnitz 2006, p. 658

- Richard Foltz, "The Tajiks of Uzbekistan", Central Asian Survey, 213-216 (1996).

- Fane 1998, p. 292-293

- Pew Global Attitudes

- Scott Radnitz, “Weighing the Political and Economic Motivations for Migration in Post-Soviet Space: The Case of Uzbekistan,” Europe-Asia Studies (July 2006): 653-677.

- Erkin Ahmadov, Fighting Illegal Labor Migration in Uzbekistan, Central Asia Caucasus-Institute Analyst, http://www.cacianalyst.org/newsite/?q=node/4681(Aug Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine. 21, 2007)

- International Organization for Migration, Uzbekistan, http://www.iom.int/jahia/Jahia/pid/510(Feb Archived 2012-03-10 at the Wayback Machine. 17, 2011).

- International Crisis Group, Uzbekistan: Stagnation and Uncertainty, Asia Briefing, 22 August 2007.

- Radnitz 2006, p. 659

- Daria Fane, “Ethnicity and Regionalism in Uzbekistan: Maintaining Stability Through Authoritarian Control,” in Leokadia Drobizheva, Rose Gottemoeller, Catherine McArdle Kelleher, and Lee Walker, ed., in Ethnic Conflict in the Post-Soviet World: Case Studies and Analysis (New York: M.E. Sharp, Inc., 1998), 271-302.