Economy of Ethiopia

The economy of Ethiopia is a mixed and transition economy with a large public sector. The government of Ethiopia is in the process of privatizing many of the state-owned businesses and moving toward a market economy.[19] However, the banking, telecommunication and transportation sectors of the economy are dominated by government-owned companies.[20][21]

Addis Ababa skyline | |

| Currency | Birr (ETB, ብር) |

|---|---|

| 7 – 8 July | |

Trade organisations | AU, AfCFTA, COMESA, IGAD, WTO (observer), G24 |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

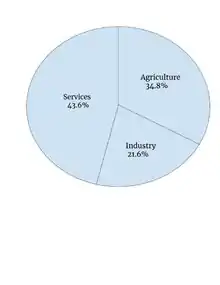

GDP by sector |

|

| 20.2% (2020 est.)[5] | |

Population below poverty line |

|

| |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Main industries | food processing, beverages, textiles, leather, chemicals, metals processing, cement |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | coffee, qat, gold, leather products, live animals, oilseeds |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | Machinery and aircraft, metal and metal products, electrical materials, petroleum products, motor vehicles, chemicals and fertilizers |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −3.2% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[3] | |

| Revenues | 11.24 billion (2017 est.)[3] |

| Expenses | 13.79 billion (2017 est.)[3] |

| Economic aid | $308 million (recipient) (2001) |

| Standard & Poor's:[16] B (Foreign currency ratings) B (Local currency ratings) B (T&C assessment), Moody's:[17] B1 (Outlook stable) Fitch:[18] B (Outlook stable) | |

Foreign reserves | |

Ethiopia has one of the fastest-growing economies in the world and is Africa's second most populous country.[22] Many properties owned by the government during the previous regime have now been privatized and are in the process of privatization.[23] However, certain sectors such as telecommunications, financial and insurance services, air and land transportation services, and retail, are considered as strategic sectors and are expected to remain under state control for the foreseeable future. Almost 50% of Ethiopia's population is under the age of 18, and even though education enrollment at primary and tertiary level has increased significantly, job creation has not caught up with the increased output from educational institutes. The country must create hundreds of thousands of jobs every year just to keep up with population growth.[24]

History

Though the issuing of minted coins didn't begin until around 270, metal coins may have been used in Aksum centuries prior to centralized minting. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentions that Aksum imported brass "which they use[d] for ornaments and for cutting as money", and that they imported "a little money (denarion) for [use with] foreigners who live there." Some outside influences encouraging the use of coins is undeniable. Roman, Himyarite, and Kushana coins have all been found in major Aksumite cities. The minting of coins began around 270 CE, beginning with the reign of Endubis.[25]

Around the 5th–8th century, the coffee plant was introduced into the Arab world from Ethiopia.[26] Coffea arabica, the most highly regarded species, is native to the southwestern highlands of Ethiopia. Long before the cultivation of coffee, however, other food crops like finger millet, teff, sorghum, lablab bean and castor bean were cultivated in Ethiopia.[27][28]

Following the overthrow of the Ethiopian monarchy a marxist military government nationalized all companies and land, expelled foreign investors, and pursued an extensive military expenditure. The Ethiopian economy significantly deteriorated due to the civil war and famines of the 1970s and 1980s. Since 1991, the Ethiopian government has embarked on a program of economic reform, including privatization of state enterprises and rationalization of government regulation.[29] While the process is still ongoing, the reforms have attracted much-needed foreign direct investment.

In 2015, Ethiopia has 2,700 millionaires, a number that has more than doubled since 2007. Their fortunes are mainly built-in niches of economic rents (banks, mines, etc.) without investing in structural and strategic sectors (industrial production, infrastructure, etc.) and should in no way promote economic development or represent a source of competition for Western multinationals.[30]

The Ethiopian government is stepping up its efforts to attract foreign investors, particularly in the textile sector. They can now import their machines without customs duties, benefit from a tax exemption for ten years, rents much lower than market prices, and almost free water and electricity. Major brands have established themselves in the country, such as Decathlon, H&M and Huajian. These companies also benefit from a cheap labor force, with a monthly salary of around 35 euros. Finally, trade agreements between Ethiopia and the European Union allow them to export duty-free.[31]

Sectors

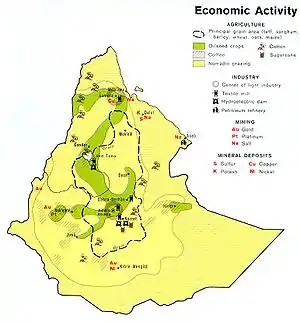

Agriculture, forestry and fishing

As of 2015, agriculture accounts for almost 40.5% of GDP, 81 percent of exports, and 85 percent of the labour force.[32] Many other economic activities depend on agriculture, including marketing, processing, and export of agricultural products. Production is overwhelmingly of a subsistence nature, and a large part of commodity exports are provided by the small agricultural cash-crop sector. Principal crops include coffee, pulses (e.g., beans), oilseeds, cereals, potatoes, sugarcane, and vegetables. Exports are almost entirely agricultural commodities, with coffee as the largest foreign exchange earner, and its flower industry becoming a new source of revenue: for 2005/2006 (the latest year available) Ethiopia's coffee exports represented 0.9% of the world exports, and oilseeds and flowers each representing 0.5%.[33] Ethiopia is Africa's second biggest maize producer.[34] In 2000, Ethiopia's livestock contributed to 19% of total GDP.[35]

As of 2008, some countries that import most of their food, such as Saudi Arabia, have begun planning the purchase and development of large tracts of arable land in developing countries such as Ethiopia.[36] This land grabbing has raised fears of food being exported to more prosperous countries while the local population faces its own shortage.[36]

Forest products are mainly logs used in construction. The silvicutural properties are used in construction and manufacturing, and as energy sources.[37][38]

Ethiopia's fisheries are entirely fresh water, as it has no marine coastline. Although total production has been continuously increasing since 2007, the fishing industry is a very small part of the economy. Fishing is predominantly artisanal. In 2014, nearly 45,000 fishermen were employed in the sector with only 30% of them employed full-time.[39]

Ethiopia produced in 2018:

- 7.3 million tons of maize (17th largest producer in the world);

- 4.9 million tons of sorghum (4th largest producer in the world);

- 4.2 million tons of wheat;

- 2.1 million tons of barley (17th largest producer in the world);

- 1.8 million tons of sweet potato (5th largest producer in the world);

- 1.4 million tons of sugar cane;

- 1.3 million tons of yam (5th largest producer in the world);

- 988 thousand tons of broad bean;

- 982 thousand tons of millet;

- 743 thousand tons of potato;

- 599 thousand tons of vegetable;

- 515 thousand tons of chick pea (6th largest producer in the world);

- 508 thousand tons of banana;

- 470 thousand tons of coffee (6th largest producer in the world);

- 446 thousand tons of cabbage;

- 374 thousand tons of pea (20th largest producer in the world);

- 322 thousand tons of onion;

- 301 thousand tons of sesame seed (7th largest producer in the world);

- 294 thousand tons of bell pepper;

- 172 thousand tons of lentil (11th largest producer in the world);

- 144 thousand tons of rice;

- 143 thousand tons of peanut;

- 140 thousand tons of cotton;

- 124 thousand tons of garlic;

- 102 thousand tons of mango (including mangosteen and guava);

- 101 thousand tons of linseed (7th largest producer in the world);

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products. [40]

Textile industry

Employees of Ethiopian garment factories, who work for brands such as Guess, H&M or Calvin Klein, receive a monthly salary of 26 dollars per month. These very low wages have led to low productivity, frequent strikes and high turnover. Some factories have replaced all their employees on average every 12 months, according to the 2019 report of the Stern Centre for Business and Human Rights at New York University

The report states:" Rather than the docile and cheap labour force promoted in Ethiopia, foreign-based suppliers have met employees who are unhappy with their pay and living conditions and who want to protest more and more by stopping work or even quitting. In their eagerness to create a "made in Ethiopia" brand, the government, global brands and foreign manufacturers did not anticipate that the base salary was simply too low for workers to make a living from. »[41]

Minerals and mining

The mining sector is small in Ethiopia. The country has deposits of coal, opal, gemstones, kaolin, iron ore, soda ash, and tantalum, but only gold is mined in significant quantities. In 2001 gold production amounted to some 3.4 tons.[42] Salt extraction from salt beds in the Afar Depression, as well as from salt springs in Dire and Afder districts in the south, is only of internal importance and only a negligible amount is exported.

On 30 August 2012 it was announced that British firm Nyota Minerals was about to become the first foreign company to receive a mining licence to extract gold from an estimated resource of 52 tonnes in western Ethiopia.[43]

Energy

Waterpower and forests are Ethiopia's main energy sources. The country derives about 90 percent of its electricity needs from hydropower, which means that electricity generation, as with agriculture, is dependent on abundant rainfall. Present installed capacity is rated at about 2000 megawatts, with planned expansion to 10,000 megawatts. In general, Ethiopians rely on forests for nearly all of their energy and construction needs; the result has been deforestation of much of the highlands during the last three decades.[42]

Less than one-half of Ethiopia's towns and cities are connected to the national grid. Petroleum requirements are met via imports of refined products, although some oil is being hauled overland from Sudan. Oil exploration in Ethiopia has been underway for decades, ever since Emperor Haile Selassie granted a 50-year concession to SOCONY-Vacuum in September 1945.[44]

Recent oil and gas discoveries across East Africa have seen the region emerge as a new player in the global oil and gas industry. As exciting as the huge gas fields of East Africa are, however, the strong decline in oil prices and expectations for an L-shaped recovery with low prices over the coming years are increasingly challenging the economic viability of the industry in this region.[45][46] The reserves are estimated at 4 trillion cubic feet (110×109 m3), while exploration for gas and oil is underway in the Gambela Region bordering Sudan.[42]

The discoveries were expected to drive billions of dollars in annual investment to the region over the next decade.[47] According to BMI estimates, the findings in the last few years are more than that of any other region in the world, and the discoveries are expected to continue for the next few years. However, falling global oil prices are threatening the commercial viability of many of these gas prospects.[48]

Manufacturing

A program to privatize state-owned enterprises has been underway since the late 1990s.[42] There has been a large growth of manufacturing in Ethiopia. Several industrial parks have been built with a focus on textiles.

Transport

Prior to the outbreak of the 1998–2000 Eritrean–Ethiopian War, landlocked Ethiopia mainly relied on the seaports of Asseb and Massawa in Eritrea for international trade. As of 2005, Ethiopia uses the ports of Djibouti, connected to Addis Ababa by the Addis Ababa – Djibouti Railway, and to a lesser extent Port Sudan in Sudan. In May 2005, the Ethiopian government began negotiations to use the port of Berbera in Somaliland.

Road

As of 2016, there are 113,066 kilometres (70,256 mi) all-weather roads.[49]

Air

Ethiopian Airlines, is Africa's largest and most profitable airline.[50] It serves 123 destinations and has a fleet size of over 100 aircraft.

Rail

The Ethiopian railway network has been rapidly expanding. In 2015, the first light rail in Africa was opening in Addis Ababa. In 2017, the electric Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway began operations. Presently, two other electric railways are under construction: Awash-Woldiya and Woldiya-Mekelle.

Telecommunications

Telecommunications are provided by a state-owned monopoly, Ethio Telecom, formerly the Ethiopian Telecommunications Corporation.

Tourism

Aside from wholesale and retail trade, transportation, and communications, the services sector consists almost entirely of tourism. Developed in the 1960s, tourism declined greatly during the later 1970s and the 1980s under the military government. Recovery began in the 1990s, but growth has been constrained by the lack of suitable hotels and other infrastructure, despite a boom in construction of small and medium-sized hotels and restaurants, and by the impact of drought, the 1998–2000 war with Eritrea, and the specter of terrorism. In 2002 more than 156,000 tourists entered the country, many of them Ethiopians visiting from abroad, spending more than US$77 million.[42] In 2008, the number of tourists entering the country had increased to 330,000.[51]

Macroeconomic trends

The following table displays the trend of Ethiopia's gross domestic product at market prices, according to estimates by the International Monetary Fund with figures in millions of Ethiopian Birr.[52]

| Year | Gross Domestic Product | GDP (USD) | US Dollar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birr (millions) | per capita | Exchange | |

| 1980 | 14,665 | 190 | 2.06 Birr |

| 1990 | 25,011 | 257 | 2.06 Birr |

| 1995 | 47,560 | 148 | 5.88 Birr |

| 2000 | 64,398 | 124 | 8.15 Birr |

| 2005 | 106,473 | 169 | 8.65 Birr |

| 2006 | 131,672 | 202 | 8.39 Birr |

| 2007 | 171,834 | 253 | 8.93 Birr |

| 2008 | 245,973 | 333 | 9.67 Birr |

| 2009 | 386,215 | 398 | 12.39 Birr |

| 2010 | 427,026 | 361 | 13.33 Birr |

| 2017 | 803,350 (est) | 846 (est) |

The current GDP (USD) per capita of Ethiopia shrank by 43% in the 1990s.[53] The economy saw continuous real GDP growth of at least 5% since 2004.

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2017. Inflation below 5% is in green.[54]

| Year | GDP (in Bil. US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 10.8 | 313 | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | n/a | |||

| 1982 | n/a | ||||

| 1983 | n/a | ||||

| 1984 | n/a | ||||

| 1985 | n/a | ||||

| 1986 | n/a | ||||

| 1987 | n/a | ||||

| 1988 | n/a | ||||

| 1989 | n/a | ||||

| 1990 | n/a | ||||

| 1991 | n/a | ||||

| 1992 | 87.1% | ||||

| 1993 | |||||

| 1994 | |||||

| 1995 | |||||

| 1996 | |||||

| 1997 | |||||

| 1998 | |||||

| 1999 | |||||

| 2000 | |||||

| 2001 | |||||

| 2002 | |||||

| 2003 | |||||

| 2004 | |||||

| 2005 | |||||

| 2006 | |||||

| 2007 | |||||

| 2008 | |||||

| 2009 | |||||

| 2010 | |||||

| 2011 | |||||

| 2012 | |||||

| 2013 | |||||

| 2014 | |||||

| 2015 | |||||

| 2016 | |||||

| 2017 |

External trade

Until 2013, the major agricultural export crop was coffee, providing about 26.4% of Ethiopia's foreign exchange earnings. In the beginning of 2014, oilseeds exports have been more important.[55] Coffee is critical to the Ethiopian economy. More than 15 million people (25% of the population) derive their livelihood from the coffee sector.[56]

.png.webp)

Other exports include live animals, leather and leather products, chemicals, gold, pulses, oilseeds, flowers, fruits and vegetables and khat (or qat), a leafy shrub which has psychotropic qualities when chewed. Cross-border trade by pastoralists is often informal and beyond state control and regulation. In East Africa, over 95% of cross-border trade is through unofficial channels and the unofficial trade of live cattle, camels, sheep and goats from Ethiopia sold to Somalia, Kenya and Djibouti generates an estimated total value of between US$250 and US$300 million annually (100 times more than the official figure).[57] This trade helps lower food prices, increase food security, relieve border tensions and promote regional integration.[57] However, there are also risks as the unregulated and undocumented nature of this trade runs risks, such as allowing disease to spread more easily across national borders. Furthermore, the government of Ethiopia is purportedly unhappy with lost tax revenue and foreign exchange revenues.[57] Recent initiatives have sought to document and regulate this trade.[57]

Dependent on a few vulnerable crops for its foreign exchange earnings and reliant on imported oil, Ethiopia lacks sufficient foreign exchange. The financially conservative government has taken measures to solve this problem, including stringent import controls and sharply reduced subsidies on retail gasoline prices. Nevertheless, the largely subsistence economy is incapable of supporting high military expenditures, drought relief, an ambitious development plan, and indispensable imports such as oil; it therefore depends on foreign assistance.

In December 1999, Ethiopia signed a $1.4 billion joint venture deal with the Malaysian oil company, Petronas, to develop a huge natural gas field in the Somali Region. By the year 2010, however, implementation failed to progress and Petronas sold its share to another oil company.[58]

See also

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "Ethiopia - Country data (IMF DataMapper, October 2020)". IMF.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) - Ethiopia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Selima., Jāhāna (2015). Work for human development (PDF). Human Development Report. United Nations Development Programme. ISBN 9789211263985. OCLC 936070939.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Labor force, total - Ethiopia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (modeled ILO estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Doing Business in Ethiopia - World Bank Group". www.doingbusiness.org. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "S&P Global Market Intelligence". www.capitaliq.com. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Moody's: Ethiopia's credit profile balances high growth and low debt costs against range of challenges". moodys.com. 1 August 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Press Release". www.fitchratings.com. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Sanchez, Dana (10 January 2017). "Ethiopia Moves Toward Privatization. It's Not about Money. It's About Tech". AFKInsider. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Maasho, Aaron (21 March 2015). "Ethiopia launches 4G mobile service in the capital". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Maasho, Aaron (29 March 2015). "Ethiopia sells off seven state firms, to offer more". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Private Sector Boosts Ethiopia's Growth". IFC. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- "Ethiopia sells off seven state firms, to offer more". Reuters. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- "A brittle Western ally in the Horn of Africa". The Economist. 1 November 2007. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart C. (1991). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity (PDF). Edinburgh University Press. pp. 151–154. ISBN 9780748601066. OCLC 24695872.

- Souza, Ricardo M. (2 September 2008). Plant-Parasitic Nematodes of Coffee. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 3, 165. ISBN 9781402087202.

- Carney, Judith (1 February 2011). In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa's Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. University of California Press. pp. 18–19, 31. ISBN 9780520949539.

Ethiopia is the birthplace of the world's premier coffee (Coffea arabica).

- Murphy, Denis J. (19 July 2007). People, Plants & Genes: The Story of Crops and Humanity. OUP Oxford. p. 95. ISBN 9780199207138. OCLC 191050253.

- Seid, Yared; Taffesse, Alemayehu S.; Ali, Seid Nuru (8 November 2016). Ethiopia—an agrarian economy in transition (PDF). Africa's Lions: Growth Traps and Opportunities for Six African Economies. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 9780815729501. OCLC 961309230.

- Piot, Olivier (1 November 2017). "Rencontre Avec Les pionniers de l'" anticapitalism "". Le Monde diplomatique.

- Gérand, Christelle (1 April 2019). "Going for textiles". Le Monde diplomatique.

- "Ethiopia. CIA The World Fact Book". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Selected Issues Series", International Monetary Fund Country Report No. 08/259, pp. 35f (Retrieved 4 February 2009)

- "Get the gangsters out of the food chain". The Economist. 7 June 2007.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (May 2004). "Livestock Sector Brief: Ethiopia" (PDF). FAO Country Profiles. FAO. p. 1. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Blas, Javier; Andrew England (20 August 2008). "Arable Land, the new gold rush". Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

Meles Zenawi, the prime minister of Ethiopia, is also enthusiastic. After welcoming a Saudi agriculture delegation a fortnight ago, he said: 'We told them [the Saudis] that we would be very eager to provide hundreds of thousands of hectares of agricultural land for investment.'

- Wakjira, Dereje T.; Gole, Tadesse W. (2007). "Customary Forest Tenure in Southwest Ethiopia". Forests, Trees and Livelihoods. 17 (4): 325–338. doi:10.1080/14728028.2007.9752607. ISSN 1472-8028.

- Lemenih, Mulugeta; Bongers, Frans (1 January 2011). Günter, Sven; Weber, Michael; Stimm, Bernd; Mosandl, Reinhard (eds.). Silviculture in the Tropics. Tropical Forestry. 8. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 261–272. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-19986-8_17. ISBN 9783642199851.

- Fisheries and Aquaculture Department (1 October 2015). "Fisheries & Aquaculture - Country Profile". Ethiopia. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Ethiopia production in 2018, by FAO

- "En Ethiopie, les petites mains de H&M ou Calvin Klein gagnent 23 euros par mois". 8 May 2019 – via Le Monde.

- Ethiopia country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (April 2005). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Newsome, Matthew (30 August 2012). "Gold mining promises big boost for Ethiopia's development" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Sinco Places a Bet", Time, 17 September 1945 (Retrieved 14 May 2009)

- "Is East Africa's gas asset boom about to go bust?". Mineweb. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Africa's exports by region | Bright Africa". www.riscura.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Oil And Gas Discoveries Near Africa's East Coast To Soon Drive Billions in Investments: PWC". International Business Times. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Krauss, Clifford (16 January 2016). "Oil Prices: What's Behind the Drop? Simple Economics". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Ethiopia - Road and Railways". export.gov. 21 June 2017.

- "Ethiopian Airlines 2015 outlook: more rapid expansion as it becomes Africa's largest airline". CAPA Centre for Aviation. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017.

- "UNdata country profile: Ethiopia". Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "What We Do". Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Oilseed overtakes coffee as Ethiopia’s top export earner" Ethiosports, 2014. (Retrieved 1 July 2014)

- "Ethiopian coffee: The best in the world?" African Business, 2001. (Retrieved 24 January 2007)

- Pavanello, Sara 2010. Working across borders - Harnessing the potential of cross-border activities to improve livelihood security in the Horn of Africa drylands. London: Overseas Development Institute

- "Petronas sells Ethiopian assets to SouthWest" Upstream Online news, 6 October 2010. (Retrieved 10 December 2010)

Further reading

- Fantu Cheru, Christopher Cramer, and Arkebe Oqubay (eds.). 2019. The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy. Oxford University Press.

- Hausmann, Ricardo; Hidalgo, César A.; Bustos, Sebastián; Coscia, Michele; Simoes, Alexander (17 January 2014). The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262525428. OCLC 836557569.

- World Bank Group (2 December 2016). Why so idle? Wages and Employment in a Crowded Labor Market (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 11 January 2017.