Foreign interventions by the United States

The United States has been involved in a number of foreign interventions throughout its history. There have been two dominant schools of thought in the United States about foreign policy, namely interventionism and isolationism which either encourage or discourage foreign intervention, both military, diplomatic, and economic, respectively.

Post-colonial

The 19th century saw the United States transition from an isolationist, post-colonial regional power to a Trans-Atlantic and Trans-Pacific power.

The first and second Barbary Wars of the early 19th century were the first nominal foreign wars waged by the United States post-Independence. Directed against the Barbary States of North Africa, the Barbary Wars were fought to end piracy against American-flagged ships in the Mediterranean Sea, similar to the Quasi-War with post-monarchical France.[1]

The founding of Liberia was privately sponsored by American groups, primarily the American Colonization Society, but the country enjoyed the support and unofficial cooperation of the United States government.[2]

The 19th century formed the roots of United States interventionism, which was largely driven by economic opportunities in the Pacific and Spanish-held Latin America along with the Monroe Doctrine, which saw the U.S. seek a policy to resist continued European colonialism in the Western hemisphere.

Notable 19th century interventions included:

- Repeated U.S. interventions in Chile, starting in 1811, the year after its independence from Spain.

- 1846 to 1848: Mexico and the United States warred over Texas, California and what today is the American Southwest but was then part of Mexico (see Mexican–American War). During this war, U.S. troops invaded and occupied parts of Mexico, including Veracruz and Mexico City.

- 1854: Matthew Perry negotiated a treaty opening Japan to the West with the Convention of Kanagawa.[3] The U.S. advanced the Open Door Policy that guaranteed equal economic access to China and support of Chinese territorial and administrative integrity.[4]

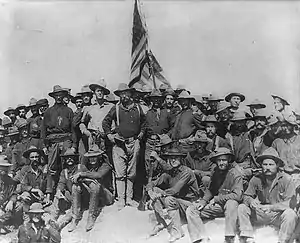

- 1898: The short but decisive Spanish–American War saw overwhelming American victories at sea and on land against the Spanish Kingdom. The U.S. Army, relying significantly on volunteers and state militia units, invaded and occupied Spanish-controlled Cuba, subsequently granting it independence. The peace treaty saw Spain cede control over its colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States.[5] The U.S. Navy set up coaling stations there and in Hawaii.[6]

The early decades of the 20th century saw a number of interventions in Latin America by the U.S. government often justified under the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.[7] President William Howard Taft viewed "Dollar Diplomacy" as a way for American corporations to benefit while assisting in the national security goal of preventing European powers from filling any possible financial or power vacuum.[8]

.jpg.webp)

- 1898 to 1935: The United States launched minor interventions into Latin America. These included military presence in Cuba, Panama with the Panama Canal Zone, Haiti (1915–35), Dominican Republic (1916–24) and Nicaragua (1912–1925) & (1926–33). The U.S. Marine Corps began to specialize in long-term military occupation of these countries, primarily to safeguard customs revenues which were the cause of local civil wars.[9]

- 1899 to 1901: The Boxer Rebellion saw an eight-nation alliance put down a rebellion by the Boxer secret society and toppled the Qing dynasty's Imperial Army.

- 1899 to 1902: The Philippine–American War saw Filipino revolutionaries revolt against American rule following the Spanish-American War. The U.S. Army deployed 100,000 (mostly National Guard) troops under General Elwell Otis to the Philippines, leading the poorly armed and poorly trained rebels to break off into armed bands. The insurgency collapsed in March 1901 when the leader Emilio Aguinaldo was captured by General Frederick Funston and his Macabebe allies.[10]

- 1899 to 1913: The Moro Rebellion saw the annexation of the Philippines by the United States.

- 1901: The Platt Amendment amended a treaty between the U.S. and Cuba after the Spanish–American War, virtually making Cuba a U.S. protectorate. The amendment outlined conditions for the U.S. to intervene in Cuban affairs and permitted the United States to lease or buy lands for the purpose of the establishing naval bases, including Guantánamo Bay.[11]

- 1903: U.S.-backed independence of Panama from Colombia in order to build the Panama Canal; Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty[12]

- 1904: When European governments began to use force to pressure Latin American countries to repay their debts, Theodore Roosevelt announced his "Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, stating that the United States would intervene in the Western Hemisphere should Latin American governments prove incapable or unstable.[13]

- 1906 to 1909: U.S. governed Cuba under Governor Charles Magoon.[14]

- 1909: U.S.-backed rebels in Nicaragua depose President José Santos Zelaya.[15]

- 1910 to 1919: The Border War along the U.S.-Mexico border saw U.S. forces occupy Veracruz for six months in 1914.

- 1914 to 1917: Mexico conflict and Pancho Villa Expedition, U.S. troops entering northern portion of Mexico.[16]

- 1912 to 1933: United States occupation of Nicaragua.

- 1914: During a revolution in the Dominican Republic, the U.S. navy fired at revolutionaries who were bombarding Puerto Plata, in order to stop the action.

- 1915 to 1934: United States occupation of Haiti.[17]

- 1916 to 1924: U.S. Marines occupied the Dominican Republic following 28 revolutions in 50 years.[18] The Marines ruled the nation completely except for lawless parts of the city of Santo Domingo, where warlords still held sway.[19]

- 1917 to 1918: The U.S. intervened in Europe during World War I. Over the next 18 months, the U.S. would suffer casualties of 116,708 killed and 204,002 wounded. U.S. troops also intervened in the Russian Civil War against the Red Army via the Polar Bear Expedition.

World War II

During the Second World War, the United States deployed troops to fight in both Europe and the Pacific. The U.S. was a key participant in many battles, including the Battle of Midway, the Normandy landings, and the Battle of the Bulge. In the time period between December 7, 1941 to September 2, 1945, more than 400,000 Americans were killed in the conflict. After the war, American and Allied troops occupied both Germany and Japan.

The United States also gave economic support to a large number of countries and movements who were opposed to the Axis powers. This included the Lend-Lease program, which "lent" a wide array of resources and weapons to many countries, especially Great Britain and the USSR, ostensibly to be repaid after the war. In practice, the United States frequently either did not push for repayment or "sold" the goods for a nominal price, such as 10% of their value. Significant aid was also sent to France and Taiwan, and resistance movements in countries occupied by the Axis.[20]

Cold War

Following the Second World War, the U.S. helped form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949 to resist communist expansion and supported resistance movements and dissidents in the communist regimes of Central and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union during a period known as the Cold War. One example is the counterespionage operations following the discovery of the Farewell Dossier which some argue contributed to the fall of the Soviet regime.[21][22] After Joseph Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade,[23] the United States, Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several other countries began the massive "Berlin airlift", supplying West Berlin with up to 4,700 tons of daily necessities.[24] U.S. Air Force pilot Gail Halvorsen created "Operation Vittles", which supplied candy to German children.[25] In May 1949, Stalin backed down and lifted the blockade.[26][27] The U.S. spent billions to rebuild Europe and aid global development through programs such as the Marshall Plan.

From 1950 to 1953, U.S. and United Nations forces fought communist Chinese and North Korean troops in the Korean War, which saw South Korea successfully defended from capture. U.S. troops have remained in South Korea to deter further conflict, as the war has not officially ended. President Harry Truman was unable to depose the North Korean government due to Chinese intervention, but the goal of containment on the Korean Peninsula was achieved.

During the Cold War, the U.S. frequently used the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for clandestine operations against governments considered unfriendly to U.S. interests, especially in the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa. In 1949, during the Truman administration, a coup d'état overthrew an elected parliamentary government in Syria, which had delayed approving an oil pipeline requested by U.S. international business interests in that region. The exact role of the CIA in the coup is controversial, but it is clear that U.S. governmental officials, including at least one CIA officer, communicated with Husni al-Za'im, the coup's organizer, prior to the March 30 coup, and were at least aware that it was being planned. Six weeks later, on May 16, Za'im approved the pipeline.[28]

In the early 1950s, the CIA spearheaded Project FF, a clandestine effort to pressure Egyptian king Farouk I into embracing pro-American political reforms. After he resisted, the project shifted towards deposing him and Farouk was subsequently overthrown in a military coup in 1952.[29] In 1953, under U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower, the CIA helped Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran remove the democratically elected Prime Minister, Mohammed Mossadegh. Supporters of U.S. policy claimed that Mossadegh had ended democracy through a rigged referendum.[30]

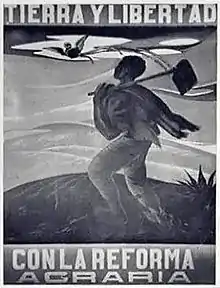

In 1954, the CIA launched Operation PBSuccess, which deposed the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz and ended the Guatemalan Revolution. The coup installed the military dictatorship of Carlos Castillo Armas, the first in a series of U.S.-backed dictators who ruled Guatemala. Guatemala subsequently plunged into a civil war that cost thousands of lives and ended all democratic expression for decades.[31][32][33]

The CIA armed an indigenous insurgency in order to oppose the invasion and subsequent control of Tibet by China[34] and sponsored a failed revolt against Indonesian President Sukarno in 1958.[35] As part of the Eisenhower Doctrine, the U.S. also deployed troops to Lebanon in Operation Blue Bat.

Covert operations continued under President John F. Kennedy and his successors. In 1961, the CIA attempted to depose Cuban president Fidel Castro through the Bay of Pigs Invasion. The invasion was doomed when President Kennedy withdrew overt U.S. air support at the last minute. The CIA also considered assassinating Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba with poisoned toothpaste (although this plan was aborted).[36][37][38] In 1961, the CIA supported the overthrow of Rafael Trujillo, dictator of the Dominican Republic.[39] After a period of instability, U.S. troops invaded the Dominican Republic in Operation Power Pack (April 1965) to prevent a Communist takeover. Without collaborators, a U.S. invasion against an army united with the people would have been difficult and costly in lives; in an optimistic estimate, the Pentagon believed that at least two full U.S. divisions were required to overcome the extensive armament the Dominican Republic had acquired as protection against a Haitian invasion.[40]

At the end of the Eisenhower administration, a campaign was initiated to deny Cheddi Jagan power in an independent Guyana.[42] This campaign was intensified and became something of an obsession of John F. Kennedy, because he feared a "second Cuba".[43] By the time Kennedy took office, the United Kingdom was ready to decolonize British Guiana and did not fear Jagan's political leanings, yet chose to cooperate in the plot for the sake of good relations with the United States.[44] The CIA cooperated with AFL-CIO, most notably in organizing an 80-day general strike in 1963, backing it up with a strike fund estimated to be over $1 million.[45] The Kennedy Administration put pressure on Harold Macmillan's government to help in its effort, ultimately attaining a promise on July 18, 1963, that Macmillan's government would unseat Jagan.[46] This was achieved through a plan developed by Duncan Sandys whereby Sandys, after feigning impartiality in a Guyanese dispute, would decide in favor of Forbes Burnham and Peter D'Aguiar, calling for new elections based on proportional representation before independence would be considered, under which Jagan's opposition would have better chances to win.[47] The plan succeeded, and the Burnham-D'Aguiar coalition took power soon after winning the election on December 7, 1964.[48] The Johnson administration later helped Burnham fix the fraudulent election of 1968—the first election after decolonization in 1966.[49] To guarantee Burnham's victory, Johnson also approved a well-timed Food for Peace loan, announced some weeks before the election so as to influence the election but not to appear to be doing so.[49] U.S.–Guyanese relations cooled in the Nixon administration. Henry Kissinger, in his memoirs, dismissed Guyana as being "invariably on the side of radicals in Third World forums."[50]

From 1965 to 1973, U.S. troops fought at the request of the governments of South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia during the Vietnam War against the military of North Vietnam and against Viet Cong, Pathet Lao, and Khmer Rouge insurgents. President Lyndon Johnson escalated U.S. involvement following the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. North Vietnam invaded Laos in 1959, and used 30,000 men to build invasion routes through Laos and Cambodia.[51] North Vietnam sent 10,000 troops to attack the south in 1964, and this figure increased to 100,000 in 1965.[52] By early 1965, 7,559 South Vietnamese hamlets had been destroyed by the Viet Cong.[53] The CIA organized Hmong tribes to fight against the Pathet Lao, and used Air America to "drop 46 million pounds of foodstuffs....transport tens of thousands of troops, conduct a highly successful photoreconnaissance program, and engage in numerous clandestine missions using night-vision glasses and state-of-the-art electronic equipment."[54] After sponsoring a coup against Ngô Đình Diệm, the CIA was asked "to coax a genuine South Vietnamese government into being" by managing development and running the Phoenix Program that killed thousands of insurgents.[55] North Vietnamese forces attempted to overrun Cambodia in 1970,[56] to which the U.S. and South Vietnam responded with a limited incursion.[57][58][59] The U.S. bombing of Cambodia, called Operation Menu, proved controversial. Although David Chandler argued that the bombing "had the effect the Americans wanted--it broke the communist encirclement of Phnom Penh,"[60] others have claimed it boosted recruitment for the Khmer Rouge.[61] North Vietnam violated the Paris Peace Accords after the US withdrew, and all of Indochina had fallen to communist governments by late 1975.

In 1975 it was revealed by the Church Committee that the United States had covertly intervened in Chile from as early as 1962, and that from 1963 to 1973, covert involvement was "extensive and continuous".[62] In 1970, at the request of President Richard Nixon, the CIA planned a "constitutional coup" to prevent the election of Marxist leader Salvador Allende in Chile, while secretly encouraging Chilean generals to act against him. The CIA changed its approach after the murder of Chilean general René Schneider,[63] offering aid to democratic protestors and other Chilean dissidents. Allende was accused of supporting armed groups, torturing detainees, conducting illegal arrests, and muzzling the press;[64] historian Mark Falcoff therefore credits the CIA with preserving democratic opposition to Allende and preventing the "consolidation" of his supposed "totalitarian project".[65] However, Peter Kornbluh asserts that the CIA destabilized Chile and helped create the conditions for the 1973 Chilean coup d'état, which led to years of dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet.[66]

In 1973, Nixon authorized Operation Nickel Grass, an overt strategic airlift to deliver weapons and supplies to Israel during the Yom Kippur War, after the Soviet Union began sending arms to Syria and Egypt. From 1972–5, the CIA armed Kurdish rebels fighting the Ba'athist government of Iraq.

Months after the Saur Revolution brought a communist regime to power in Afghanistan, the U.S. began offering limited financial aid to Afghan dissidents through Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence, although the Carter administration rejected Pakistani requests to provide arms.[67] After the Iranian Revolution, the United States sought rapprochement with the Afghan government—a prospect that the USSR found unacceptable due to the weakening Soviet leverage over the regime.[68] The Soviets invaded Afghanistan on December 24, 1979 to depose Hafizullah Amin, and subsequently installed a puppet regime. Disgusted by the collapse of detente, President Jimmy Carter began covertly arming Afghan mujahideen in a program called Operation Cyclone.

This program was greatly expanded under President Ronald Reagan as part of the Reagan Doctrine. As part of this doctrine, the CIA also supported the UNITA movement in Angola,[69] the Solidarity movement in Poland,[70] the Contra revolt in Nicaragua, and the Khmer People's National Liberation Front in Cambodia.[71][72] U.S. and UN forces later supervised free elections in Cambodia.[73] Under Reagan, the US sent troops to Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War as part of a peace-keeping mission. The U.S. withdrew after 241 servicemen were killed in the Beirut barracks bombing. In Operation Earnest Will, U.S. warships escorted reflagged Kuwaiti oil tankers to protect them from Iranian attacks during the Iran–Iraq War. The United States Navy launched Operation Praying Mantis in retaliation for the Iranian mining of the Persian Gulf during the war and the subsequent damage to an American warship. The attack helped pressure Iran to agree to a ceasefire with Iraq later that summer, ending the eight-year war.[74] Under Carter and Reagan, the CIA repeatedly intervened to prevent right-wing coups in El Salvador and the U.S. frequently threatened aid suspensions to curtail government atrocities in the Salvadoran Civil War. As a result, the death squads made plans to kill the U.S. Ambassador.[75] In 1983, after an internal power struggle ended with the deposition and murder of revolutionary Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, the U.S. invaded Grenada in Operation Urgent Fury and held free elections. In 1986, the U.S. bombed Libya in response to Libyan involvement in international terrorism. President George H. W. Bush ordered the invasion of Panama (Operation Just Cause) in 1989 and deposed dictator Manuel Noriega.[76]

A 2016 study by Carnegie Mellon University professor Dov Levin found that the United States intervened in 81 foreign elections between 1946 and 2000, with the majority of those being through covert, rather than overt, actions.[77][78]

Post-Cold War

In 1990-91, the U.S. intervened in Kuwait after a series of failed diplomatic negotiations, and led a coalition to repel invading Iraqi forces led by Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, in what became known as the Gulf War. On 26 February 1991, the coalition succeeded in driving out the Iraqi forces. The U.S., UK, and France responded to popular Shia and Kurdish demands for no-fly zones, and intervened and created no-fly zones in Iraq's south and north to protect the Shia and Kurdish populations from Saddam's regime. The no-fly zones cut off Saddam from the country's Kurdish north, effectively granting autonomy to the Kurds, and would stay active for 12 years until the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In the 1990s, the U.S. intervened in Somalia as part of UNOSOM I, a United Nations humanitarian relief operation[79] that resulted in saving hundreds of thousands of lives.[80] During the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, two U.S. helicopters were shot down by rocket-propelled grenade attacks to their tail rotors, trapping soldiers behind enemy lines. This resulted in a brief but bitter street firefight; 18 Americans and more than 300 Somalis were killed.

Under President Bill Clinton, the U.S. participated in Operation Uphold Democracy, a UN mission to reinstate the elected president of Haiti, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, after a military coup.[81] In 1995, Clinton ordered US and NATO aircraft to attack Bosnian Serb targets to halt attacks on UN safe zones and to pressure them into a peace accord. Clinton deployed U.S. peacekeepers to Bosnia in late 1995, to uphold the subsequent Dayton Agreement. In response to the 1998 al-Qaeda bombings of U.S. embassies in East Africa that killed a dozen Americans and hundreds of Africans, Clinton ordered cruise missile strikes on targets in Afghanistan and Sudan. First was the Sudanese Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory, suspected of assisting Osama Bin Laden in making chemical weapons. The second was Bin Laden's terrorist training camps in Afghanistan.[82]

Also, to stop the ethnic cleansing and genocide[83][84] of Albanians by nationalist Serbians in the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia's province of Kosovo, Clinton authorized the use of U.S. Armed Forces in a NATO bombing campaign against Yugoslavia in 1999, named Operation Allied Force.

The CIA was involved in the failed 1996 coup attempt against Saddam Hussein.[85]

In 1998, the U.S. became involved in major paramilitary efforts in Colombia (Plan Colombia) to eliminate drug trafficking.

War on terror

After the September 11, 2001 attacks, under President George W. Bush, the U.S. and NATO launched the War on Terror, which saw an intervention to depose the Taliban government in the Afghan War and launch drone attacks in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia against suspected terrorist targets.[86][87] In 2003, the U.S. and a multi-national coalition invaded Iraq to depose Saddam Hussein. As of 2021, Afghanistan continues to host U.S. and NATO counterinsurgency operations under the aegis of Operation Resolute Support and Operation Freedom's Sentinel, while the Iraq War officially ended on December 18, 2011. The U.S. has used large amounts of aid and counterinsurgency training to enhance stability and reduce violence in war-ravaged Colombia, in what has been called "the most successful nation-building exercise by the United States in this century".[88]

The U.S. intervened in the 2011 Libyan Civil War by providing air support to rebel forces. There was also speculation in The Washington Post that President Barack Obama issued a covert action, discovering in March 2011 that Obama authorized the CIA to carry out a clandestine effort to provide arms and support to the Libyan opposition.[89] Muammar Gaddafi was ultimately overthrown and killed.

.jpg.webp)

Beginning around 2012, under the aegis of operation Timber Sycamore and other clandestine activities, CIA operatives and U.S. special operations troops trained and armed nearly 10,000 Syrian rebel fighters[91] at a cost of $1 billion a year until it was phased out in 2017.[92][93][94][95]

2013–2014 saw the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) terror organization in the Middle East. In June 2014, the U.S. re-intervened into Iraq and began airstrikes against ISIL there in response to prior gains by the terrorist group that threatened U.S. assets and Iraqi government forces. This was followed by more airstrikes on ISIL in Syria in September 2014,[96] where the U.S.-led coalition targeted ISIL positions throughout the war-ravaged nation. Initial airstrikes involved fighters, bombers, and launching Tomahawk cruise missiles.

In March 2015, President Barack Obama declared that he had authorized U.S. forces to provide logistical and intelligence support to the Saudis in their military intervention in Yemen, establishing a "Joint Planning Cell" with Saudi Arabia.[97]

A 2016 study published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution (published by the University of Maryland) analyzing U.S. military interventions in the period 1981–2005 found that the U.S. "is likely to engage in military campaigns for humanitarian reasons that focus on human rights protection rather than for its own security interests such as democracy promotion or terrorism reduction."[98]

See also

- United States involvement in regime change

- American imperialism

- American exceptionalism

- United States territorial acquisitions

- List of armed conflicts involving the United States

- List of the lengths of United States participation in wars

- Military history of the United States

- Historic regions of the United States

- Manifest Destiny

- Foreign interventions by the Soviet Union

- Foreign interventions by China

- Foreign interventions by Cuba

- Foreign electoral intervention

- New Imperialism

References

- John Pike. "Barbary Wars". globalsecurity.org.

- Flint, John E. The Cambridge History of Africa: from c.1790 to c.1870 Cambridge University Press (1976) pg 184-199

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Open Door policy". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "The Philippines". Digital History. University of Houston. 22 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

In December, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States for $20 million.

- William Braisted, United States Navy in the Pacific, 1897–1909 (2008)

- "Home - Theodore Roosevelt Association". theodoreroosevelt.org.

- "Dollar Diplomacy". americanforeignrelations.com.

- Lester D. Langley, The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898–1934 (2001)

- Brian McAllister Linn, The Philippine War 1899–1902 (University Press of Kansas, 2000). ISBN 0-7006-0990-3

- "Our Documents - Platt Amendment (1903)". ourdocuments.gov.

- "Panama declares independence". HISTORY.com.

- "Our Documents - Theodore Roosevelt's Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (1905)". ourdocuments.gov.

- Lockmiller, David A. (January 1, 1937). "Agriculture in Cuba during the Second United States Intervention, 1906-1909". Agricultural History. 11 (3): 181–188. JSTOR 3739793.

- "Nicaragua timeline". BBC News. November 9, 2011.

- "United States Interventions in Mexico, 1914-1917". Archived from the original on March 27, 2004.

- U.S. Invasion and Occupation of Haiti, 1915-34

- "Presidential Key Events". millercenter.org.

- "US Occupation of the Dominican Republic".

- Ebbert, Jean, Marie-Beth Hall & Beach, Edward Latimer (1999). Crossed Currents. p. 28. ISBN 9781574881936.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "CIA slipped bugs to Soviets". Washington Post. NBC. Archived from the original on February 29, 2004. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- "The Farewell Dossier". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- Gaddis 2005, p. 33

- Nash, Gary B. "The Next Steps: The Marshall Plan, NATO, and NSC-68." The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society. New York: Pearson Longman, 2008. P 828.

- Miller 2000, p. 26

- Gaddis 2005, p. 34

- Miller 2000, pp. 180–81

- Wilford, Hugh (2013). America's Great Game: The CIA's Secret Arabists and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Basic Books. pp. 94, 101. ISBN 9780465019656.

- Holland, Matthew F. (July 11, 1996). America and Egypt: From Roosevelt to Eisenhower. Praeger. p. 27. ISBN 978-0275954741.

- "New York Times Special Report: The C.I.A. in Iran". The New York Times.

- Briggs, Billy (February 2, 2007). "Billy Briggs on the atrocities of Guatemala's civil war". The Guardian. London.

- "Timeline: Guatemala". BBC News. November 9, 2011.

- CDI: The Center for Defense Information, The Defense Monitor, "The World At War: January 1, 1998".

- Conboy, Kenneth and Morrison, James, The CIA's Secret War in Tibet (2002).

- Road night, Andrew (2002). United States Policy towards Indonesia in the Truman and Eisenhower Years. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-79315-3.

- "ASSASSINATION PLANNING AND THE PLOTS A. CONGO" (PDF).

- M. Crawford Young (1966). "Post-Independence Politics in the Congo". Transition (26): 34–41. JSTOR 2934325.

- Gott 2004 p. 219.

- Blanton, William, ed. (May 8, 1973), Memorandum for the Executive Secretary, CIA Management Committee. Subject: Potentially Embarrassing Agency Activities, George Washington University National Security Archives Electronic Briefing Book No. 222, The CIA's Family Jewels

- De La Pedraja, René (April 15, 2013). Wars of Latin America, 1948–1982: The Rise of the Guerrillas. McFarland. p. 149.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (1999). The Most Dangerous Area in the World: John F. Kennedy Confronts Communist Revolution in Latin America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina press. pp. 86–88. ISBN 080784764X.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 8, 123. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 110–112. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 106, 119–122. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 137. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 157–160. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (2005). U.S. intervention in British Guiana: a Cold War story. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 168–169. ISBN 0-8078-5639-8.

- The Economist, February 26, 1983.

- Washington Post, April 23, 1985.

- Readers Digest, "The Blood-Red Hands of Ho Chi Minh", November 1968.

- Leary, William M. "CIA Air Operations in Laos, 1955-1974." CIA. June 27, 2008. https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/winter99-00/art7.html

- Powers, The Man who kept the Secrets (1979) at 198-201, 203, 204-206, 209-212.

- Dmitry Mosyakov, "The Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese Communists: A History of Their Relations as Told in the Soviet Archives," in Susan E. Cook, ed., Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda (Yale Genocide Studies Program Monograph Series No. 1, 2004), p54ff. "In April–May 1970, many North Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in response to the call for help addressed to Vietnam not by Pol Pot, but by his deputy Nuon Chea. Nguyen Co Thach recalls: "Nuon Chea has asked for help and we have liberated five provinces of Cambodia in ten days."

- The Economist, February 26, 1983.

- Washington Post, April 23, 1985.

- Rodman, Peter, Returning to Cambodia, Brookings Institution, August 23, 2007.

- Chandler, David 2000, Brother Number One: A Political Biography of Pol Pot, Revised Edition, Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, pp. 96-7.

- Shawcross, William (1979). Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. University of Michigan. ISBN 0-671-23070-0.

- Church Committee (1975). "Covert Action in Chile: 1963-1973". pp. 14–15, 1.

- Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders (1975), Church Committee, pages 246–247 and 250–254.

- "Declaration on the Breakdown of Chile's Democracy," Resolution of the Chamber of Deputies, Chile, August 22, 1973. See also The Wall Street Journal's "What Really Happened in Chile"* "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 16, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Falcoff, Mark, Kissinger and Chile, Commentary, 2003.

- Kornbluh, Peter (2003). The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability. New York: The New Press. ISBN 1-56584-936-1.

- Robert M. Gates (2007). From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider's Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War. Simon Schuster. p. 146. ISBN 9781416543367. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- Rubin, Michael, "Who is Responsible for the Taliban?", Middle East Review of International Affairs, Vol. 6, No. 1 (March 2002).

- John Pike. "UNITA Uniao Nacional para a Independecia Total de Angola". globalsecurity.org.

- MacEachin, Douglas J. "US Intelligence and the Polish Crisis 1980-1981." CIA. June 28, 2008.

- "Cambodia at a Crossroads", by Michael Johns, The World and I magazine, February 1988

- Far Eastern Economic Review, December 22, 1988, details the extensive fighting between the U.S.-backed forces and the Khmer Rouge.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 745. S/RES/745(1992) 28 February 1992. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- Peniston, Bradley (2006). No Higher Honor: Saving the USS Samuel B. Roberts in the Persian Gulf. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-661-5., p. 217.

- Washington Post, February 24, July 13, 1980 (Carter); New York Times, November 20, 26, December 12, 1983 (Reagan); New York Times, June 24, 1984, Washington Post, June 27, 1984 (Ambassador)

- "Noriega extradited to France". CNN. April 26, 2010.

- Levin, Dov H. (June 2016). "When the Great Power Gets a Vote: The Effects of Great Power Electoral Interventions on Election Results". International Studies Quarterly. 60 (2): 189–202. doi:10.1093/isq/sqv016.

- The U.S. is no stranger to interfering in the elections of other countries, Los Angeles Times, (December 21, 2016).

- "UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN SOMALIA I - (UNOSOM I)". United Nations.

- "The United States Army in Somalia, 1992-1994". U.S. Army.

- John R. Ballard, Upholding Democracy: The United States Military Campaign in Haiti, 1994–1997 (1998)

- Pike, John. "BGM-109 Tomahawk – Smart Weapons". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- Cohen, William (April 7, 1999). "Secretary Cohen's Press Conference at NATO Headquarters Archived May 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- Clinton, Bill (June 25, 1999). "Press Conference by the President ". Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- Association of Former Intelligence Officers (May 19, 2003), US Coup Plotting in Iraq, Weekly Intelligence Notes 19-03

- Currier, Cora (February 5, 2013). "Everything We Know So Far About Drone Strikes". ProPublica. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- "The Drone Papers". The Intercept. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Boot, Max; Richard Bennet (December 14, 2009). "The Colombian Miracle". The Weekly Standard. 15 (13).

- Jaffe, Greg (March 30, 2011). "In Libya, CIA is gathering intelligence on rebels". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- "U.S. carrier moving off coast of Yemen to block Iranian arms shipments". USA Today. 20 April 2015.

- "U.S. has secretly provided arms training to Syria rebels from 2012". Los Angeles Times. June 21, 2013.

- "Secret CIA effort in Syria faces large funding cut". The Washington Post. June 12, 2015.

- Jaffe, Greg; Entous, Adam (July 19, 2017). "Trump ends covert CIA program to arm anti-Assad rebels in Syria, a move sought by Moscow". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Ignatius, David (July 20, 2017). "What the demise of the CIA's anti-Assad program means". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- Ali Watkins (July 21, 2017). "Top general confirms end to secret U.S. program in Syria". Politico. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Julian E. Barnes and Dion Nissenbaum (August 7, 2014). "U.S., Arab Allies Launch Airstrikes Against Islamic State Targets in Syria". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- "Saudi Arabia launces air attacks in Yemen". The Washington Post. March 25, 2015.

- Choi, Seung-Whan; James, Patrick (August 1, 2016). "Why Does the United States Intervene Abroad? Democracy, Human Rights Violations, and Terrorism". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 60 (5): 899–926. doi:10.1177/0022002714560350. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 54867507.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: American benevolence |

- Judis, John B. (2004). "Imperial Amnesia". Foreign Policy (143): 50–59. doi:10.2307/4152911. JSTOR 4152911. (Alternate link)

- The Truth About U.S. Middle East Policy, from The Middle East Review of International Affairs

- “When the Great Power Gets A Vote: The Effects of Great Power Electoral Interventions on Election Results” by Dov H. Levin