Fukushima (city)

Fukushima (福島市, Fukushima-shi, [ɸɯ̥kɯꜜɕima]) is the capital city of Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. It is located in the northern part of the Nakadōri, central region of the prefecture. As of 1 June 2019, the city has an estimated population of 287,357 in 122,130 households[2] and a population density of 374 inhabitants per square kilometre (970/sq mi). The total area of the city is 767.72 square kilometres (296.42 sq mi).[3]

Fukushima

福島市 | |

|---|---|

Fukushima City | |

Flag  Seal | |

Location of Fukushima in Fukushima Prefecture | |

Fukushima | |

| Coordinates: 37°45′38.9″N 140°28′29″E | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Tōhoku |

| Prefecture | Fukushima |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Hiroshi Kohata |

| Area | |

| • Total | 767.72 km2 (296.42 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 67 m (220 ft) |

| Population (1 June 2019) | |

| • Total | 287,357 |

| • Density | 370/km2 (970/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| - Tree | Zelkova serrata[1] |

| - Flower | Peach[1] |

| - Bird | Great tit[1] |

| Phone number | 024-535-1111 |

| Address | 3-1 Gorōuchimachi, Fukushima-shi, Fukushima-ken 960–8601 |

| Website | Official website |

The present-day city of Fukushima partially consists of most of the former Shinobu and Date Districts and a portion of the former Adachi District. The city is located in the Fukushima Basin's southwest area and nearby mountains.

There are many onsen on the outskirts of the city, including the resort areas of Iizaka Onsen, Takayu Onsen, and Tsuchiyu Onsen. Fukushima is also the location of the Fukushima Race Course, the only Japan Racing Association horse racing track in the Tōhoku region of Japan.

Geography

Fukushima is located in the central northeast section of Fukushima Prefecture, approximately 50 km (31 mi) east of Lake Inawashiro, 250 km (160 mi) north of Tokyo, and about 80 km (50 mi) south of Sendai. It lies between the Ōu Mountains to the west and the Abukuma Highlands to the east. Most of the city is within the southeast area and nearby mountains of the Fukushima Basin. Mt. Azuma and Mt. Adatara loom over the city from the west and southwest, respectively

In the north, Fukushima is adjacent to the Miyagi Prefecture cities of Shiroishi and Shichikashuku. In the northwest, Fukushima borders the Yamagata Prefecture cities of Yonezawa and Takahata. Within Fukushima Prefecture, to the west of Fukushima is the town of Inawashiro, to the south is Nihonmatsu, to the east are Kawamata and Date, and to the northeast is Koori.[4]

Terrain

The Fukushima Basin is created by the surrounding Ōu Mountains in the west and the Abukuma Highlands in the east, with the Abukuma River flowing through the center of the basin, from south to north. Multiple tributaries to the Abukuma River source in the Ōu Mountains before flowing down into Fukushima, namely the Surikami, Matsukawa, and Arakawa rivers. These rivers flow eastward through the western side of the city until joining up with the Abukuma River in the central parts of the city. The irrigation from these rivers were formerly used for the cultivation of mullberry trees; however, in the latter half of the 20th century cultivation was switched from focusing on mullberry trees, and instead growing a variety of fruit orchards.

The highest point within the city limits is Mt. Higashi-Azuma, a 1,974 m (6,476 ft) peak of Mt. Azuma, located on the western edge of the city. The lowest point is the neighborhood of Mukaisenoue (向瀬上), which is in the northeastern part of the city and has an elevation of 55 m (180 ft). Mt. Shinobu, 276 m (906 ft) a monadnock, lies in the southeastern section of the Fukushima Basin and is a symbol of the city.

The Abukuma River flows north-south through the central area of Fukushima and joins with many tributaries on its journey through the city. The Arakawa River originates from Mt. Azuma and flows eastward, eventually flowing into the Abukuma River near the city center. The Matsukawa River, which flows eastward from its origin in Mt. Azuma and also joins with the Abukuma River in the northern part of the city. Another major tributary of the Abukuma River is the Surikami River, which originates along the Fukushima-Yamagata prefectural border near the Moniwa area in the northwest of the city. From there it flows into Lake Moniwa, a reservoir created by the Surikamigawa Dam. From there it continues flowing southeast before meeting up with the Abukuma River in northern Fukushima, thus completing its 32 km (20 mi) run.

.jpg.webp)

Other tributaries of the Abukuma River which flow within Fukushima are the Kohata (木幡川), Megami (女神川), Mizuhara (水原), Tatsuta (立田川), Shimoasa (下浅川), Tazawa (田沢川), Iri (入川), Ōmori (大森川), and Hattanda (八反田川) rivers. The Oguni River (小国川) also flows through the city and is a tributary of the Hirose River (広瀬川), which itself is also a tributary of the Abukuma River, however the Oguni River doesn't meet up with the Hirose River until the district of Date, outside of the Fukushima city limits.

There are multiple lakes in the area of Fukushima that falls within Bandai-Asahi National Park. Goshiki-numa (五色沼, Five-colored Lake), also called Majo no Hitomi (魔女の瞳, The Witch's Eye) is a caldera lake located in Mt. Azuma's Mt. Issaikyō peak. The lake is so-named due its water color changing in relation to weather conditions. Lake Kama (鎌沼) and Lake Oke (桶沼) are also located in Bandai-Asahi National Park.[5]

In the Tsuchiyu area in the western part of the city lie the small lakes of Lake Me (女沼), Lake O (男沼), and Lake Nida (仁田沼). In the neighborhood of Watari (渡利) lies Lake Chaya (茶屋沼). Lake Jūroku (十六沼) is in the Ōzasō (大笹生) neighborhood.

Neighbouring municipalities

- Fukushima Prefecture

- Yamagata Prefecture

- Miyagi Prefecture

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Fukushima has a humid subtropical climate. There is often a large temperature and weather difference between central Fukushima versus the mountains on the edge of the city. The hottest month tends to be August, with an average high of 30.4 °C (86.7 °F) in central Fukushima, at an elevation of 67 metres (220 ft), while Tsuchiyu Pass on the western edge of the city and at an elevation of 1,220 metres (4,003 ft) has an average August high of 21.7 °C (71.1 °F). The coldest month tends to be January, with an average low of −1.8 °C (28.8 °F) in central Fukushima and −9.0 °C (15.8 °F) on Tsuchiyu Pass.[6][7]

On average, central Fukushima receives 1,166.0 mm (45.91 in) of precipitation annually and receives 0.5 mm (0.020 in) or more of precipitation on 125.2 days per year. An average of 189 cm (74 in) of snow falls annually, with 22.9 days receiving 5 cm (2.0 in) or more of snow. An average of 74 cm (29 in) of snow falls in January, making it the snowiest month. Central Fukushima also receives an average of 1,738.8 hours of sunshine per year, significantly more than the 1,166.5 hours received at Tsuchiyu Pass.[6][7]

| Climate data for Central Fukushima, elevation of 67 metres (220 ft), located at 37°45.5′N 140°28.2′E (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.8 (64.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

36.7 (98.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.9 (102.0) |

37.3 (99.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

27.1 (80.8) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.6 (90.7) |

35.1 (95.2) |

35.7 (96.3) |

32.8 (91.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

36.4 (97.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.5 (41.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.4 (86.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.6 (34.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

16.6 (61.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −6 (21) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

0.1 (32.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−1 (30) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.2 (13.6) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 49.4 (1.94) |

44.3 (1.74) |

75.6 (2.98) |

81.0 (3.19) |

92.6 (3.65) |

122.1 (4.81) |

160.4 (6.31) |

154.0 (6.06) |

160.3 (6.31) |

119.1 (4.69) |

65.5 (2.58) |

41.8 (1.65) |

1,166 (45.91) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 74 (29) |

57 (22) |

24 (9.4) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

28 (11) |

189 (74) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ ≧0.5mm) | 10.8 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 11.8 | 14.7 | 11.4 | 12.3 | 9.6 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 125.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ ≧5cm) | 9.9 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 22.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68 | 64 | 61 | 59 | 63 | 72 | 77 | 75 | 76 | 72 | 69 | 68 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132.0 | 142.3 | 174.2 | 186.4 | 187.5 | 136.6 | 123.6 | 152.5 | 114.2 | 135.8 | 128.3 | 125.2 | 1,738.8 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[6] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Moniwa, elevation of 200 meters, located at 37°53.5′N 140°26.2′E (1992–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

28.4 (83.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

12.8 (55.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.2 (37.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 100.9 (3.97) |

63.3 (2.49) |

82.2 (3.24) |

84.5 (3.33) |

97.6 (3.84) |

127.6 (5.02) |

186.3 (7.33) |

175.9 (6.93) |

160.9 (6.33) |

115.3 (4.54) |

91.9 (3.62) |

95.9 (3.78) |

1,384.9 (54.52) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 156 (61) |

116 (46) |

43 (17) |

5 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (1.2) |

69 (27) |

393 (155) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ ≧1.0mm) | 15.6 | 12.4 | 12.6 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 12.6 | 14.4 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 10.4 | 12.2 | 14.9 | 150.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ ≧5cm) | 21.9 | 19.8 | 5.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 6.9 | 55.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 82.0 | 99.3 | 136.3 | 157.3 | 167.0 | 135.1 | 124.5 | 136.9 | 105.6 | 116.5 | 97.6 | 79.0 | 1,439.4 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[8] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Tsuchiyu Pass, elevation of 1,220 meters, located at 37°40.1′N 140°15.6′E (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

0.2 (32.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.4 (20.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

14.0 (57.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −9.0 (15.8) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

5.2 (41.4) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 40.4 | 62.1 | 105.6 | 156.8 | 166.8 | 128.2 | 107.9 | 125.2 | 86.0 | 87.9 | 63.6 | 39.3 | 1,166.5 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Association[7] | |||||||||||||

Population

Fukushima has the third-highest population in the prefecture, behind the cities of Iwaki, with 377,288, and Kōriyama, with 336,328.[9][4] This makes Fukushima the only prefectural capital in Japan that is the third-largest city in the prefecture.

The Fukushima metropolitan area had a May 2011 estimated population of 452,912 and consisted of the towns and cities of Nihonmatsu, Date, Kunimi, Koori, Kawamata, and Fukushima. It is the second most populous metropolitan area in Fukushima Prefecture, with the Kōriyama metropolitan area being the largest with a population of 553,996.[9][10] The Fukushima metropolitan area is also the sixth-largest metropolitan area in the Tōhoku region.

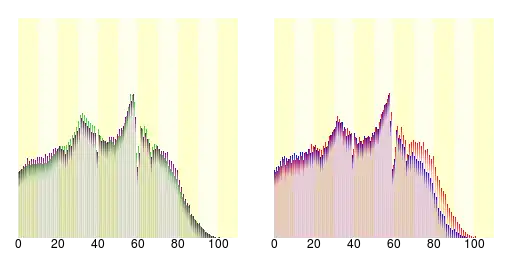

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comparison of Population Distribution between Fukushima and Japanese National Average | Population Distribution by Age and Sex in Fukushima | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

■Fukushima ■Japan (average) |

■Male ■Female | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 Census, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications - Statistics Department | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

Jōmon period to 11th century AD

During the times of ancient Japan, the area now known as the city of Fukushima was called Minekoshi (岑越). The mountain in the middle of the city, present-day Mt. Shinobu, was also formerly called Mt. Minekoshi (岑越山).

During the Jōmon period, for around 2,000 years there was a large settlement on the eastern bank of the Abukuma River. This site has since been excavated and named the Miyahata Site.

It is said that in the 5th century AD, Kumano Atai (久麻直) was appointed by the Yamato court (大和朝廷) to be the Shinobu Kuni no miyatsuko (信夫国造), giving him control over the Fukushima Basin.

Under the Nara period's Ritsuryō system, stations were established along the Seven Circuits so that officials could change horses. One of the stations, the Tōsandō, passed through the area of present-day Fukushima, and Minekoshi Station was established on the route. Minekoshi Station was located south of the Surikami River and north of the Matsukawa River, which at the time flowed to the south of Mt. Minekoshi. The area south of the Matsukawa River was then, as it still is now, known as Suginome (杉妻). Thus it is believed that the station was located north of the area around the present-day prefectural office, in the Kita-gorōuchi area (北五老内地域).

The implementation of the Ritsuryō system also resulted in administrative changes, with the area of present-day Fukushima and Date being combined to form the district of Shinobu. This was the northernmost point of the Mutsu Province and held responsibility for preventing the southern expansion of the Emishi, a people who lived in northern Honshū.

After 718, and the widening influence of the Yamato Imperial Court, Mutsu Province was expanded northwards into present-day Miyagi Prefecture. Along with this redrawing of boundaries, present-day Fukushima Prefecture was separated from the new Mutsu Province (approximately present-day Miyagi) and split between the newly formed provinces of Iwaki in the east and Iwase in the west. However, by 724 Mutsu Province was unable to deal on its own with the economic costs of holding back the Emishi, so Iwaki and Iwase provinces were merged back into Mutsu.

In the first half of the 10th century, the Date district was separated from the Shinobu district. As a reform to the sōyōchō (租庸調) tax on rice, labor, and textiles, there was a nationwide effort from the Imperial Court to split up districts so they each had approximately the same population. This was accomplished both through administrative changes and forced population relocations. With Mutsu Province viewed as reclaimed land by the Imperial Court, the area saw a significant amount of reorganization.

In the late Heian period, almost the entirety of the Tōhoku region was ruled by the Northern Fujiwara clan. Relatives of the Northern Fujiwara clan, the Shinobu Satō clan (信夫佐藤氏) was given domain over nearly the entirety of present-day Fukushima Prefecture's centrally-located Nakadōri area and eventually expanded their control to include Aizu to the west as well. It is said that the Shinobu Satō clan is one of the reasons for the Satō surname spreading throughout and eventually becoming the most common surname in Japan.

12th century to 18th century

In 1180, Minamoto no Yoshitsune, was accompanied by Shinobu district residents Satō Tsugunobu (佐藤継信) and Satō Tadanobu (佐藤忠信) on his way south to Kantō to fight the Taira clan in the Genpei War.

.jpg.webp)

In 1413, Date Mochimune (伊達持宗) shut himself inside Daibutsu Castle (大仏城) in defiance of the Kamakura kubō. This is the first known historical mention of Daibutsu Castle, which was near the confluence of the Abukuma and Arakawa rivers at the present-day location of the Fukushima Prefectural Offices. It is said that the castle was named after the "Suginome Great Buddha" (杉妻大仏, Suginome Daibutsu), a Vairocana Buddha statue kept within the castle. The castle was also known as Suginome Castle (杉妻城).[11] It is believed that in this time period the area's name was changed from Minekoshi to Suginome (杉妻) to reflect the concentration of political power in the area.

During the Azuchi–Momoyama period, in 1591 Gamō Ujisato gained control of the Shinobu and Date districts, and under him Kimura Yoshikiyo (木村吉清) took control of Ōmori Castle (大森城), which was in the southwest of present-day Fukushima. The following year he moved from Ōmori Castle to Suginome Castle. It is said that, inspired by the recent renaming of Kurogawa-jō (黒川城, "Black River Castle") to the more joyous-sounding Wakamatsu-jō (若松城, "Young Pine Castle"), he changed the name of his new residence to Fukushima-jō (福島城, "Lucky Island Castle").[11]

In 1600, Date Masamune and Honjō Shigenaga, who was under the Uesugi clan and head of Fukushima Castle at the time, fought the Battle of Matsukawa (松川の戦い). At the time, the Matsukawa River flowed in a different riverbed than it does now, as the current Matsukawa River is north of Mt. Shinobu, while the Matsukawa River at the time of the battle flowed south of Mt. Shinobu. It is said that the Battle of Matsukawa's battlefield extended from the southern base of Mt. Shinobu and extended into the center of modern-day Fukushima. In 1664 the Uesugi clan lost direct control of the Shinobu district, and the area became directly ruled by the Tokugawa shogunate.

In 1702, the Fukushima Domain was established and governed from Fukushima Castle, and in 1787, the Shimomura Domain (下村藩) was established in the present-day Sakurashimo area in the western part of Fukushima. This domain was later abolished in 1823.

19th century

On November 17, 1868, Itakura Katsumi (板倉勝己), the head of the Fukushima Domain, surrendered to the Satchō Alliance and handed over control of Fukushima Castle to Watanabe Kiyoshi (渡辺清). The Fukushima Domain was abolished the following year. In line with the abolition of domains and introduction of the prefecture system, the first iteration of Fukushima Prefecture came into being on August 29, 1871. The prefecture at the time consisted of the Shinobu, Date, and Adachi districts.

With permission from the Ministry of the Treasury, on September 10, 1871 the village of Fukushima (福島村, Fukushima-mura) changed its name to the town of Fukushima (福島町, Fukushima-machi). On November 2 Fukushima Prefecture was absorbed into Nihonmatsu Prefecture (二本松県), thus making Nihonmatsu Prefecture consist of approximately the entirety of the Nakadōri area. Twelve days later, on November 14, Nihonmatsu Prefecture's name was changed to Fukushima Prefecture. Fukushima was named the prefecture's capital.

Nearly five years later, on August 21, 1876, Fukushima Prefecture merged with Iwasaki Prefecture (磐前県) (consisting of the coastal Hamadōri area) and Wakamatsu Prefecture (若松県) (consisting of Aizu in the west), thus creating present-day Fukushima Prefecture. Fukushima continued to serve as the prefecture's capital. In 1879, the Shinobu district's government offices were moved to Fukushima.

On November 3, 1881, National Route 13 (國道13號, Kokudō Jūsan-gō), which generally followed a portion of the old Ushū Kaidō, was opened and linked Fukushima to Yonezawa, approximately 45 km to the northwest. On December 15, 1887 the section of the Tōhoku Main Line running through Fukushima, connecting Kōriyama Station in the south to Iwakiri Station in the north, was opened. In Fukushima, this saw the opening of Fukushima Station and Matsukawa Station.

In 1888, there was a large-scale merger of municipalities. In the Date district, the village of Yuno (湯野村) absorbed the village of Higashiyuno (東湯野村), the villages of Kamioguni (上小国村) and Shimooguni (下小国村) merged to form the village of Oguni (小国村), the villages of Tatsukoyama (立小山) and Aoki (青木村) merged to form the village of Tatsuki (立木村). In the Adachi district, the village of Shimokawasaki (下川崎村) absorbed the village of Numabukuro (沼袋村). In the Shinobu district, the village of Kamiiizaka (上飯坂村) became the town of Iizaka (飯坂町). The Shinobu district reduced one town and 70 villages down to two towns and 26 villages.

1890 saw the opening of the Tri-District Joint Association Hospital (三郡共立組合病院), which was the predecessor of Fukushima Medical University. On March 19, 1893 Mt. Azuma's Mt. Issaikyō peak erupted, and on May 15, 1899 Fukushima was linked to Yonezawa by rail via the opening of the Ōu South Line (奥羽南線), part of the present-day Ōu Main Line. The opening of Niwasaka Station corresponded with the opening of the line. Also in 1899, a Bank of Japan branch was established in Fukushima, the bank's first branch in the Tōhoku region.

Turn of the century to end of World War II

On April 1, 1907, the town of Fukushima officially became the city of Fukushima (福島市, Fukushima-shi). It was the second municipality in the prefecture and 59th in the nation to become a city. At the time, Fukushima had a population of 30,000.

On April 14, 1908, the Shintatsu Tramway Company (信達軌道会社) opened a light rail system that connected Fukushima Rail Stop (福島停車場) to Yuno (湯野) via Nagaoka (長岡). Also in 1908, the Fukushima City Library (福島市立図書館) opened.

On June 28, 1918, the Fukushima Race Course held its first horse race. On August 30 of the same year, rice riots occurred in the city.

On April 13, 1924, the Fukushima Iizaka Electric Tramway, precursor to the present-day Iizaka Line, began service linking Fukushima Station to Iizaka Station (present-day Hanamizuzaka Station). Three years later, in 1927, the line was extended further north to its present-day terminus of Iizaka Onsen Station. 1927 also saw the opening of Fukushima Building (福島ビル) and with it the prefecture's first elevator. In 1929 the Fukushima City Library closed and the Fukushima Prefectural Library (県立図書館) opened in its place, taking over the Fukushima City Library's collections and facilities. 1929 also saw the beginning of bus service within the city.

In 1937, a section of the village of Noda (野田村) was absorbed into Fukushima, and in 1939 Yumoto Credit Financing Association (湯元信用無尽株式会社) took over Fukushima Finance Association (福島無尽株式会社), changed its name to Fukushima Finance Provider (株式会社福島無尽金庫), and moved its head office to Fukushima. This was the precursor to the present-day Fukushima Bank (株式会社福島銀行).

In 1941, NHK opened its first broadcast station in the city. Near the end of World War II, in which Japan had initiated wars with a number of Pacific powers to create the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, on July 20, 1945, a United States Army Air Forces Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombed the Watari area.

Post-war

In 1946, Toho Bank moved its head office to Fukushima, on June 18, 1947 Fukushima Prefecture Girl's Medical School (福島県立女子医学専門学校) became Fukushima Medical University, and on March 7, 1948 the Fukushima Prefecture Police Department was dismantled and the Fukushima City Police formed.

On April 27, 1948, at 12:04 am, a train on the Ōu Main Line bound for Ueno derailed upon exiting a tunnel between Akaiwa and Niwasaka stations, killing three crew members. Upon inspection of the crash scene it was determined that someone had removed from the track two connecting plates, six spikes, and four bolts. The perpetrator was never found. This became known as the Niwasaka incident.

On August 17, 1949, at 3:09 am the Matsukawa incident occurred. In a scene highly reminiscent of the scene from the previous year's Niwasaka incident, a train bound for Ueno derailed, killing three crew members. Inspection of the tracks revealed that connecting plates and spikes had been removed. Furthermore, a 25 m (82 ft) 925 kg (2,039 lb) section of rail had been moved 13 m (43 ft) from the track. No one was ever convicted of the crime. 1949 also saw the opening of Fukushima University.

In 1952, a new city hall was opened in the Gorōuchi (五老内町) neighborhood. The Seventh National Sports Festival of Japan was also held in the city, and in 1954 the present-day Fukushima Prefectural Office's main wing was completed and the Fukushima City Police were integrated into the Fukushima Prefecture Police. In March 1959 NHK began television broadcasts. Later that year, on May 11, the Bandai-Azuma Skyline tourist roadway opened.

In January 1966, the Kitamachi Route 4 bypass was completed, and on May 29 the 2,376 metres (7,795 ft) Kuriko Tunnel (栗子トンネル) on Route 13 was opened.

The very first Waraji Festival (わらじ祭り) was held on August 1, 1970. In the festival participants parade a large waraji straw sandal through the streets of Fukushima. Two months later, on November 1, Route13's Mt. Shinobu Tunnel (信夫山トンネル). The Iizaka East Line was shut down on April 12, 1971, leaving the Iizaka Line the only remaining railway operated by Fukushima Transportation. The same year Fukushima Prefectural Office's west wing was completed, making it, at the time, the tallest building in the prefecture. The section of the Tōhoku Expressway linking Kōriyama in the south to Shiroishi in the north, via Fukushima, opened on April 1, 1975. The Tōhoku Shinkansen opened on June 23, 1982 and connected Ōmiya in the south to Morioka in the north, via Fukushima.

The Route 4 South Bypass opened on November 11, 1983, and the Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art and Prefectural Library were completed on July 22, 1983. Fukushima hosted the first East Japan Women's Ekiden road relay race on November 24, 1985.

On August 4 and 5 of 1986 the Abukuma River and its tributaries flooded due to Nakdōri receiving from 200 to 300 mm (7.9 to 11.8 in) of rain from a typhoon. Cities and towns along the Abukuma River and its tributaries, Fukushima included, suffered 11 people killed or injured, and damage to 14,000 buildings.

Later that year, on September 13, the Fukushima Azuma Stadium was completed. The Abukuma Express Line, a 54.9 km (34.1 mi) railway line linking Fukushima to Marumori in the north, began operations on July 1, 1988, and on November 12, the Yūji Koseki Memorial Museum was opened.

The Fukushima Mutual Bank changed its name to Fukushima Bank in February 1989, and on September 27 Route 115's 3,360 m (11,020 ft) Tsuchiyu Tunnel (土湯トンネル) was opened. On July 1, 1992 the Yamagata Shinkansen opened, connecting Fukushima to Yamagata. In 1995, the 50th National Sports Festival of Japan was held, primarily at Azuma Sports Park in the west of the city.

The dam completion ceremony for the Surikamigawa Dam in the Moniwa area was held on September 25, 2005.

April 1, 2007 was the 100th anniversary of Fukushima becoming a city, and to celebrate, a dashi (山車, a type of parade float) festival was held on June 30. Dashi representing the former towns and villages that make up modern-day Fukushima paraded and gathered in front of Fukushima Station.

During the Great Heisei Merger, Fukushima and the towns of Kawamata and Iino held merger talks, however on December 1, 2006, Kawamata withdrew from the talks. Negotiations between Fukushima and Iino continued, and on July 1, 2008, the town of Iino was incorporated into Fukushima.

21st century

On January 4, 2011, Fukushima officially opened a new city hall to replace the previous one built in 1952. The new city hall, as was the previous one, is located in Gorōuchi-machi, next to National Route 4 in the center of the city.

On March 11, 2011, the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami occurred, with the earthquake causing ruptures in multiple water mains originating from the Surikamigawa Dam, which supplies much of the city's water. This resulted in the majority of the city losing access to running water.[12] Train services were also stopped due to damage caused to railway infrastructure. The Iizaka Line reopened two days later on March 13,[13] and on March 31 the Yamagata Shinkansen resumed limited service and the Ōu Main Line resumed full service.[14] By April 7 the Tōhoku Main Line was reopened in both directions, however it was closed again following a strong earthquake later that night. The Tōhoku Main Line was again reopened in both directions from Fukushima on April 17.[15] The Tōhoku Shinkansen reopened with limited service on April 23,[16] and the Abukuma Express Line resumed limited service from Fukushima on April 28.[17]

On April 1, 2018, City became a core city.

Government

Fukushima has a mayor-council form of government with a directly elected mayor and a unicameral city legislature of 35 members. The city also contributes eight members to the Fukushima Prefectural Assembly. In terms of national politics, most of the city falls within the Fukushima 1st district, a single-member constituency of the House of Representatives in the national Diet of Japan, which also includes the cities of Date, Sōma, Minamisōma and Date District and Sōma District.

Economy

As of 2005, the total income of all citizens of Fukushima totalled ¥1.108 trillion. Of this income, 0.8% was made in the primary sector, 24.1% in the secondary sector, and 80.1% in the tertiary sector.[18]

Income in the primary sector was led by that from agriculture, which totaled ¥8.939 billion . The secondary sector was led by general manufacturing, with income there totaling ¥218.4 billion. The service industry led the tertiary sector with a total income of ¥271.6 billion.[18]

Company headquarters located within Fukushima include that of Toho Bank, Fukushima Bank, and Daiyu Eight.

Agriculture

The majority of Fukushima's agricultural economic output is from planting crops. As of 2010, out of a total agricultural monetary yield of ¥20.83 billion, crops accounted for ¥19.14 billion and livestock accounted for ¥1.68 billion. Of crops planted in Fukushima, fruit comprises 60% of monetary yield, rice 13%, vegetables 12%, and other various crops round out the final 15%. For livestock, both milk and chicken led production with values of ¥640 million each.[19]

Fruits by far make up the largest value of crops grown in Fukushima, led by an annual production of 14,935 tons of apples, 13,200 tons of Japanese pears, and 11,517 tons of peaches. While Fukushima produces more apples and pears than peaches, as a percentage of national fruit production, in 2010 Fukushima produced 8.2% of all peaches grown in the country, compared to 5.1% of all Japanese pears and 2.3% of all apples. When the neighboring cities of Date, Kunimi and Koori, all of which are also in the Fukushima Basin, are taken into effect, the Fukushima metro area produced 20.1% of all peaches grown in Japan in 2010.[19][20] The city is known for its many peach, pear, apple, and cherry orchards which are located throughout the city, especially along the so-called Fruit Line (フルーツライン) road that loops the western edge of the city. Fukushima is also sometimes known as the Fruit Kingdom (くだもの王国).[21]

Industry

In 2009 Fukushima's industries directly employed 18,678 workers and shipped ¥671 billion worth of goods. This was led by information-related industries with 50.5% of total output. Other industries in Fukushima include those dealing with food at 7.6% of total output, metals at 7.5%, chemistry at 5.3%, ceramics at 4.9%, electricity at 4.5%, printed goods at 2.8%, steel at 2.5%, plastics at 2.5%, and electronics at 2.2%. Other various industries make up the final 9.8%.[22]

In 2009, the value of goods shipped by Fukushima's industries comprised 14.2% of all of Fukushima Prefecture's total output for the year.[22]

Commerce

For the year of 2007, wholesale products sold in Fukushima totalled ¥494 billion and employed 6,645 workers, while retail sales for the same time period totalled ¥319 billion, and employed 18,767 workers. Total combined sales of both retail and wholesale products in 2007 came to ¥813 billion, approximately a quarter less than sales in 1997 a decade prior.[23]

Transportation

Due to Fukushima having long been the junction of the Ōshū Kaidō and Ushū Kaidō routes, it has developed into an important transportation hub. It is currently the location of where National Route 13 breaks off from National Route 4. Fukushima Station is where the Ōu Main Line separates from the Tōhoku Main Line and the Tōhoku Shinkansen separates from the Yamagata Shinkansen.

Railway

In addition to the Tōhoku and Yamagata shinkansen, JR East also provides service from Fukushima Station on the Tōhoku Main Line and Ōu Main Line routes. Fukushima Station is 272.8 km (169.5 mi) north of Tokyo via the Tōhoku Main Line, which then continues north to Morioka Station. The Ōu Main Line originates at Fukushima Station then runs 484.5 km (301.1 mi) north to Aomori Station, taking a more western route than the Tōhoku Main Line. Train services are also provided by Fukushima Transportation and AbukumaExpress, which respectively run the Iizaka Line and the Abukuma Express Line. The Iizaka Line is a commuter train which connects the center of the city to Iizaka in the north of the city. The Abukuma Express Line takes a route following the Abukuma River and connects the city to Miyagi Prefecture in the north.

.svg.png.webp) East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Tōhoku Shinkansen / Yamagata Shinkansen

East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Tōhoku Shinkansen / Yamagata Shinkansen

- Station in the city: Fukushima

.svg.png.webp) JR East - Tohoku Main Line

JR East - Tohoku Main Line

.svg.png.webp) JR East - Ōu Main Line (Yamagata Line)

JR East - Ōu Main Line (Yamagata Line)

- AbukumaExpress - Abukuma Express Line

- Fukushima Transportation - Iizaka Line

- Fukushima - Soneda - Bijutsukantoshokanmae - Iwashiroshimizu - Izumi - Kamimatsukawa -Sasaya - Sakuramizu - Hirano - Iohji-mae - Hanamizuzaka - Iizaka Onsen

Highway

For automobile traffic, Fukushima is linked to Tokyo in the south and Aomori in the north via the Tōhoku Expressway, which passes through Fukushima and has multiple interchanges within the city. There are six national highways that run from or through Fukushima. Japan National Route 4 runs to Tokyo in the south, through Fukushima, then north to Sendai and beyond; Japan National Route 13 begins in Fukushima, runs through Yamagata Prefecture, then terminates in Akita Prefecture; Japan National Route 114 starts in Fukushima and runs southeast to the town of Namie; Japan National Route 115 runs through Fukushima, connecting Sōma in the east to Inwashiro in the west; Japan National Route 399 starts southeast of Fukushima in the city of Iwaki, Fukushima, continues northwest through Fukushima, and terminates in the city of Nan'yō, Yamagata; and Japan National Route 459 begins in Niigata, Niigata, runs eastward through Kitakata, through Fukushima, southward to Nihonmatsu, then eastward to Namie.

.png.webp) Tōhoku Expressway

Tōhoku Expressway.png.webp) Tōhoku-Chūō Expressway

Tōhoku-Chūō Expressway National Route 4

National Route 4 National Route 13

National Route 13 National Route 114

National Route 114 National Route 115

National Route 115 National Route 399

National Route 399 National Route 459

National Route 459

Also within the city is the Bandai-Azuma Skyline scenic toll road, which runs up and along Mt. Azuma on the western edge of the city, connecting Takayu Onsen and Tsuchiyu Onsen.

Local bus services throughout the city and region are primarily operated by Fukushima Transportation. Local bus service to the Kawamata area is offered by both JR Bus Tōhoku and Kanehachi Taxi. Intercity buses are operated by a multitude of companies and link Fukushima to the cities of Iwaki, Aizuwakamatsu, and Kōriyama within the prefectures and to the Sendai, Tokyo, and Kinki areas outside the prefecture, among others.

Airports

There is no commercial airport within the city limits. For air transportation, Fukushima is served by both Fukushima Airport in the city of Sukagawa and Sendai Airport in Natori, Miyagi.

Education

In addition to libraries and museums, Fukushima is home to many facilities for higher, secondary, and primary education

Museums located in Fukushima include the Yūji Koseki Memorial Museum (福島市古関裕而記念館),[24] the Fukushima City Museum of Photography (福島市写真美術館),[25] the Fukushima City Iino UFO Contact Museum (福島市飯野UFOふれあい館),[26] and the Fukushima Prefecture History Center (福島県歴史資料館).[27] Fukushima is also the location of the Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art, located near Bijutsukantoshokanmae Station. The museum houses 2,200 works, including French Impressionism, 20th century American realism, Japanese modern paintings, prints, earthenwares, ceramics and textiles.[28]

Fukushima operates 19 libraries and library branches throughout the city,[29] and is also home to the Fukushima Prefectural Library, which is administered by Fukushima Prefecture and is adjacent to the Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art.[30]

Institutes of higher learning that are located in Fukushima include Fukushima University, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima College, and Sakura no Seibo Junior College.

Senior high schools

Senior high schools in Fukushima are operated by both Fukushima Prefecture and private companies.

| Prefectural senior high schools[31] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Private senior high schools (5) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Junior high schools

Most junior high schools within the city are operated by the Fukushima City Board of Education, however two junior high schools are privately operated, and one, Fukushima University Attached Junior High School, is a national school run by Fukushima University.

| National junior high schools (1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| City junior high schools (21)[37] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Private junior high schools (2) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Elementary schools

The Fukushima City Board of Education operates the majority of elementary schools in the city. However, Fukushima University operates a single national elementary school while Sakura no Seibo operates a private elementary school.

| National elementary schools (1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| City elementary schools (51)[37] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Private elementary schools (1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Special assistance schools

Various special assistance schools for the blind, handicapped, and other general disabilities are operated by Fukushima University, Fukushima Prefecture, and Fukushima City.

| National special assistance schools (1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Prefectural special assistance schools (4)[31] | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| City special assistance schools (1)[37] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Notes

- Fukushima Tourist Office Information Pamphlet - "A Letter from Fukushima."

- Fukushima City official population statistics(in Japanese)

- Fukushima City official profile(in Japanese)

- 福島都市圏総合都市交通体系予備調査 [Fukushima Municipal Area General State of Transportation Preliminary Investigation] (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- 磐梯朝日国立公園 (磐梯吾妻・猪苗代地域)Bandai-Asahi National Park (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- 気象庁|平年値 (年・月ごとの値) (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- 気象庁|過去の気象データ検索. Japan Meteorological Association. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- 気象庁|過去の気象データ検索 (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- 市町村別人口動態(平成23年3月1日~平成23年4月30日) [Individual City Population Movements (1 March 2011 - 30 April 2011)] (in Japanese). Fukushima City. Archived from the original (XLS) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- 郡山都市圏パーソンとリップ調査サイト 調査の目的・概要 [Kōriyama Municipal Area Person-trip Investigation Site Investigation Purpose and Overview] (in Japanese). Fukushima Prefecture. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- 『福島のあゆみ』編集委員会 ("The Progression of Fukushima" Editing Association), ed. (31 March 1969) [1967]. 福島のあゆみ [The Progression of Fukushima] (in Japanese). 福島市教育委員会 (Fukushima City Board of Education). pp. 24–30.

- 摺上川ダム送水を停止 県内各地で断水. Fukushima Minpo. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- 福島の飯坂電車、運転再開へ (in Japanese). MSN 産経ニュース. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- 少しずつ「復旧」実感 山形新幹線が一部運転再開 [Feeling Restoration Happen Little By Little: A Section of the Yamagata Shinkansen Reopens]. Yamagata News Online. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- 山形新幹線は12日に全線再開、福島 - 仙台間に「新幹線リレー号」運転 [Yamagata Shinkansen Fully Open On the 12th, "Shinkansen Relay" Open Between Fukushima and Sendai]. マイナビニュース. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- 仙台―東京「はやぶさ」8分短縮 半年ぶりダイヤ復旧. Asahi Shimbun. Japan. 23 September 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- 阿武隈急行線 福島ー瀬上間が運転を再開 [Abukuma Express Line Reopens Fukushima to Senoue Section] (in Japanese). 鉄道ファン. 28 April 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- 平成19年版福島市統計書 [2009 Fukushima City Statistics Book] (in Japanese). Fukushima City. March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- 「市町村の姿」 -福島県- ["Condition of Cities" -Fukushima Prefecture-] (in Japanese). Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- 政府統計の総合窓口 GL08020103 [Government Statistics General Window GL08020103] (in Japanese). Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Statistics Division. 12 December 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- くだもの王国ふくしま [Fruit Kingdome Fukushima] (in Japanese). 福島県くだもの消費拡大委員会. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- 平成21年 工業統計調査結果報告書 [2009 Report on Results of Industrial Statistics Investigation] (PDF) (in Japanese). Fukushima City. November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- 平成19年商業統計調査結果報告書 [2007 Report on Results of Commerce Statistics Investigation] (in Japanese). Fukushima City. March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- 福島市古関裕而記念館 [Yūji Koseki Memorial Hall] (in Japanese). 福島市古関裕而記念館. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- 福島市写真美術館 [Fukushima City Museum of Photography] (in Japanese). 福島市写真美術館. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- UFOの里 [UFO Country] (in Japanese). 福島市UFOふれあい館. 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- 福島県歴史資料館 暫定公式ホームページ [Fukushima Prefecture History Center Temporary Home Page] (in Japanese). 福島県歴史資料館. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- "Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art". Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- 施設案内-福島市ホームページ [Facility Information - Fukushima City Home Page] (in Japanese). Fukushima City. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- 福島県立図書館 [Fukushima Prefectural Library]. Fukushima Prefectural Library. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- 県立学校一覧 [Prefectural School List] (in Japanese). Fukushima Prefecture. Archived from the original on 2011-10-18. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- 学校法人松韻学園福島高等学校 [Educational Foundation of Shōin Academy Fukushima High School] (in Japanese). Shōin Academy Fukushima High School. Archived from the original on 2012-04-22. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- 学校法人 福島成蹊学園 [Educational Foundation of Fukushima Seikei Academy] (in Japanese). Fukushima Seikei Academy. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- 福島東稜高等学校 学校法人東稜学園 [Fukushima Tōryō Educational Foundation of Tōryō Academy] (in Japanese). Fukushima Tōryō Educational Foundation of Tōryō Academy. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- 桜の聖母学院 [Sakura no Seibo Academy] (in Japanese). Sakura no Seibo Academy. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- 福島大学付属中学校 [Fukushima University Attached Junior High School] (in Japanese). Fukushima University Attached junior High School. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- 市町村立学校一覧 [Municipal Schools List] (in Japanese). Fukushiam Prefecture. Archived from the original on 2012-09-29. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- 福島大学付属小学校 [Fukushima University Attached Elementary School] (in Japanese). Fukushima University Attached Elementary School. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- 福島大学付属特別支援学校 [Fukushima University Attached Special Assistance School]. Fukushima University Attached Special Assistance School. Archived from the original on 31 July 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

References

- Takeda, Toru; Hishinuma, Tomio; Kamieda, Kinuyo; Dale, Leigh; Oguma, Chiyoichi (August 10, 1988), Hello! Fukushima - International Exchange Guide Book (1988 ed.), Fukushima City: Fukushima Mimpo Press

External links

![]() Media related to Fukushima, Fukushima at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fukushima, Fukushima at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Fukushima travel guide from Wikivoyage

Fukushima travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Official Website (in Japanese)

- Fukushima City Tourism and Convention Association official website (in Japanese)

- Fukushima City Tourism and Convention Association official website (in English)