Malaysian art

Traditional Malaysian art is primarily composed of Malay art and Bornean art, is very similar with the other styles from Southeast Asia, such as Bruneian, Indonesian and Singaporean. Art has a long tradition in Malaysia, with Malay art that dating back to the Malay sultanates, has always been influenced by Chinese, Indian and Islamic arts, and also present, due to large population of Chinese and Indian in today's Malaysian demographics.

Colonialism also brought other art forms, such as Portuguese dances and music. During this era, influences from Portuguese, Dutch, and the British, were also visible especially in terms of fashion and architecture in many colonial towns of Malaya and Borneo such as Penang, Malacca, Kuala Lumpur, Kuching and Jesselton. Despite the influences of aboard, the indigenous art of Malaysia continues to survive among the Orang Asli of peninsular and numerous ethnic groups in Sarawak and Sabah.

Nowadays, given the globally influenced and advanced technology, the younger generation of Malaysian artists have moved from the traditional material such as wood, metals, and forest products, and becoming actively involved in different forms of arts, such as animation, photography, painting, sculpture, and street art. Many of them attaining international recognition for their artworks and exhibitions worldwide, combining styles from all over the world with the traditional Malaysian traditions.

Architecture

Various cultural influences, notably Chinese, Indian and Europeans, played a major role in forming Malaysian architecture. Until recent time, wood was the principal material used for all Malaysian traditional buildings. However, numerous stone structures were also discovered particularly the religious complexes from the time of ancient Malay kingdoms. Throughout many decades, the traditional Malaysian architecture has been influenced by Buginese and Javanese from the south, Islamic, Siamese, and Indian from the north, Portuguese, Dutch, British, Acehnese and Minangkabau from the west and southern Chinese from the east.[1]

Ancient: The evidence of candi (pantheon) around south Kedah between the mount Jerai and the Muda valley, a sprawling historical complex known as Bujang valley served as a reminder of Malaysian pre-Islamic art. Within an area of about 350 square kilometres, 87 early historic religious sites have been reported and there are 12 candis located on mountain tops, a feature which suggests may derive from pre-Islamic Malay beliefs regarding the sanctity of high places.[2]

An early reference to Malaysian architecture can be found in several Chinese records. A 7th-century Chinese account tells of Buddhist pilgrims calling at Langkasuka and mentioned the city as being surrounded by a wall on which towers had been built and was approached through double gates.[3] Another 7th-century account of a special Chinese envoy to Red Earth kingdom in West Malaysia, recorded that the capital city had three gates more than a hundred paces apart, which were decorated with paintings of Buddhist themes and female spirits.[4]

Classical: The first detailed description of Malay architecture was on the great wooden palace of Mansur Shah of Malacca (reigned 1458–1477).[5] The Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals) had references to the construction and the architecture of Malacca's palaces. According to this historical document, the building had a raised seven-bay structures on wooden pillars with a seven-tiered roof in cooper shingles and decorated with gilded spires and Chinese glass mirrors.[6]

The traditional Malay houses are built using simple timber-frame structure. They have pitched roofs, porches in the front, high ceilings, many openings on the walls for ventilation,[7] and are often embellished with elaborate wood carvings. The beauty and quality of Malay wood carvings were meant to serve as visual indicators of the social rank and status of the owners themselves.[8] With the migration of Acehnese, Minangkabau, Javanese, Banjarese and Buginese, regional Malay architectural style with influences from other parts of the archipelago also exists, especially in places where they formed the majority.

Bornean: Many indigenous people of Borneo, the Dayak and Kadazandusun, live in buildings known as longhouses. Commonly, the longhouses are built raised off the ground on stilts similar to the Malay houses but are divided into a more or less public area along one side and a row of private living quarters lined along the other side. The entire architecture is designed and built as a standing tree with branches to the right and left with the front part facing the sunrise while the back faces the sunset. The longhouse building acts as the normal accommodation and a house of worship for religious activities.

In some parts of Sabah and Labuan, a substantial number of indigenous people like the Bajau and Bruneian Malay still remain to live in water villages. These water villages are also built on stilts, with houses connected with planks and most transport by traditional boats. The floating of rubbish and sewage on the water is still a persisting issue in many of these villages despite substantial measures and initiatives taken by various government and non-government agencies.

Colonial: Most of Malaysia's colonial buildings were built toward the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. These buildings have Mughal, Tudor Revival, Gothic Revival or Straits Eclectic style of architecture. Most of the styling has been modified to cater to the use of local resources and acclimatised to the local Malaysian climate, which is hot and humid all year round. Buildings with Mughal, Tudor Revival and Gothic Revival style of architecture were built by the colonial power, the British while the Chinese influenced Straits eclectic styles are common in many urban centres around Malaysia where Chinese settlers lived.

Malacca, which was a traditional centre of trade in the region, has a large variety of building styles, ranging from Islamic and Chinese styles to those brought by European colonists (Portuguese, Dutch, British). Along with Malacca, Penang is also considered one of the architectural gems of Malaysia. With its colonial-style government buildings, churches, squares, fortifications, and multicultural heritage, both Malacca and George Town demonstrate a unique architectural and cultural townscape without parallel anywhere in East and Southeast Asia.

Modern: Several design elements of traditional Malaysian architecture are adapted to modern structures to reflect the Malaysian identity. Wood, an important element in traditional Malay buildings, is also reinterpreted and readapted in the modern landscape in the Kuala Lumpur International Airport and Putrajaya. Some of these buildings also incorporated Islamic geometric motifs and designs, such as square patterns or a dome. With the help of modern technology, Malaysian firms are developing skyscraper designs that are specifically for Malaysia's tropical climates.

The stilt elevated undulating roof structure of the KLIA is supposed to imitate the traditional Malay-styled raised village houses. In Putrajaya, the Prime Minister's office is lined with wood panels to achieve the design goal. The underside of the KLIA's domed roof structure is similarly "clad in narrow strips of wood" which the architect suggests, "alludes to vernacular Malaysian timber structures, reinterpreting traditional building methods and strengthening the sense of local identity".

The remains of an ancient temple in Bujang valley, Kedah. It is believed that the area was home to the earliest civilisation in the region.

The remains of an ancient temple in Bujang valley, Kedah. It is believed that the area was home to the earliest civilisation in the region. The replica of the Malacca's palace, which was built in Malacca from information and data obtained from the Sejarah Melayu.

The replica of the Malacca's palace, which was built in Malacca from information and data obtained from the Sejarah Melayu..jpg.webp) The traditional Malay architecture of Masjid Kampung Laut in Kelantan. It is believed to be the oldest surviving mosque in Malaysia.

The traditional Malay architecture of Masjid Kampung Laut in Kelantan. It is believed to be the oldest surviving mosque in Malaysia.

.jpg.webp) The Kuala Lumpur Railway Station, notable for its architecture, adopting a mixture of eastern and western designs.

The Kuala Lumpur Railway Station, notable for its architecture, adopting a mixture of eastern and western designs. The modern architecture of KLIA was inspired by the traditional Malay architecture.

The modern architecture of KLIA was inspired by the traditional Malay architecture.

Performing art

Malaysians have diverse kinds of music, dance, theatre, and martial arts which are fusions of different cultural influences. Typical genres range from traditional Malay folk dances dramas such as mak yong to the Arab-influenced zapin dances. Choreographed movements also vary from simple steps and tunes in dikir barat to the complicated moves in joget gamelan. This diverse kinds of Malaysian performing art reflect the various cultural groups within Malaysia.

Music

Traditional Malaysian music is basically percussive. Various kinds of gongs provide the beat for many dances. There are also drums of various sizes, ranging from the large Kelantanese rebana ubi (bass drum) used to punctuate important events to the small jingled-rebana (frame drum) used as an accompaniment to vocal recitations in religious ceremonies.[9]

Nobat music has been a part of the royal regalia of Malay courts since the arrival of Islam in the 12th century and only performed in important court ceremonies. Its orchestra includes the sacred and highly revered instruments of nehara (kettledrums), gendang (double-headed drums), nafiri (trumpet), serunai (oboe), and sometimes a knobbed gong and a pair of cymbals.[10]

Traditional Malaysian music also includes; Johor with its ghazal Melayu; Malacca with its dondang sayang; Negeri Sembilan with its bongai and tumbuk kalang; Kelantan with its dikir barat and rebana ubi; Sabah with their kulintangan, isun-isun and sompoton; Sarawak with their bermukun,[11] engkromong and sape; Perak with its belotah[12]and rebana Perak; Penang with its unique boria[13] and ghazal Parti; Selangor with its cempuling[14] and keroncong; Terengganu with its middle-eastern inspired rodat and kertuk ulu.

Dance

Malaysian dance is also tremendously diverse, as each ethnic group has its own dances. Among the ethnic Malay majority, there are several traditional dances performed widely at cultural festivals and other special occasions, such as joget and zapin. In the royal courts, there is also a series of complex court dances developed throughout the centuries which require great skill. Some of the more widely known are joget gamelan, inai, and asyik dances.

Other well-known Malaysian dances are; mak inang from Malacca; ulek mayang from Terengganu; canggung and layang mas from Perlis, ngajat from Sarawak; mangunatip, mongigol and sumazau from Sabah. On the other hand, the Chinese communities also brought their traditional lion dance and dragon dance with them, while Indians brought art forms such as bharata natyam and bhangra.

Theatre

Theatrical arts in Malaysia has its root in rituals and also serves as folks' entertainment. Notable Malaysian performing arts include ritual dances, dance drama that retelling the ancient epics, legends, and stories; also wayang kulit, a traditional shadow puppet show.

Shadow Puppetry: Indian and Javanese influences are strong in the traditional Malaysian shadow play known as wayang kulit. The stories from Indian epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as stories from the Javanese Panji tales formed the main repertoire of the play.

There are four distinctive types of shadow puppet theatre that can be found in Malaysia; wayang gedek, wayang purwa, wayang Melayu and wayang Siam.[15][16][17] Nonetheless, the art and the storytelling of wayang purwa and wayang Siam denote a regional influence infused with the Javanese and Siamese respectively, while wayang Melayu and wayang gedek narrated a more indigenous Malay form and fashion.

Dance-drama: Dance, drama and traditional music in Malaysia are usually merged as a whole complete of performing art form. The traditional Malaysian dance drama art form includes; awang batil in Perlis; mak yong,[18] menora, tok selampit in Kelantan; hamdolok in Johor; randai and tukang kaba in Negeri Sembilan; jikey,[19] mek mulung[20] in Kedah; bangsawan in Malacca and Penang.

Martial art

Archaeological evidence reveals that, by the 6th century, formalised combat arts were being practised in Malaysia.[21] The earliest forms of silat are believed to have been developed and used in the armed forces of the ancient Malay kingdoms of Langkasuka (2nd century).[22][23]

The influence of the Malay sultanates of Malacca, Johor, Patani and Brunei has contributed to the spread of this martial art in the Malay archipelago. Through a complex maze of sea channels and river capillaries that facilitated exchange and trade throughout the region, silat wound its way into the dense rainforest and up into the mountains. Apart from silat, tomoi is also practised by the Malays, mainly in the northern region of Malaysia. It is a variant of Indochinese forms of kickboxing which is believed to have been spread in mainland southeast Asia since the time of the Kingdom of Funan (68 AD).

On the other hand, in Sarawak, the Ibans are known for their kuntau, a martial art passed down by their ancestors and practised from generation and generation. Until today, kuntau remains guarded by secrecy, seldom shown to the public, and rarely taught outside the community. Though traditionally passed within the family, it has dwindled in popularity among the young.

Visual art

Several design elements of traditional Malaysian arts are adapted to modern structures to reflect the Malaysian identity. The entrance to the Petronas Twin Towers is adorned with contemporary Malay motifs adapted from traditional handicrafts, including songket and timber carvings inspired by images of the tropical rainforests.[24]

Metalwork

.jpg.webp)

Malaysian metalworks assumed a role more than a mere instrumental tool. It serves as a testament of culture, cultivated by artistic appreciation and religious symbols, moulded by a craftsman who possessed a talent to redefined the essence of nature in the most ornamental manner. Upon the turn of the 17th century, iron, gold, silver, and brass have all been perfectly moulded to become part and parcel to the Malay society.

Goldwork: The art of casting gold were predominantly done by repoussé and granulation techniques, in which the traditional methods can still be witnessed until today. There are also a number of other prominent items in the Malay regalia cast in gold, including ceremonial box, tepak sirih (a betel container) and parts of kris (a peculiar Malay dagger). In the contemporary era, the Malay gold jewels are mainly found in the form of anklets, bracelets, rings, necklaces, pendants and earrings.[25][26]

Silverwork: The works of silver are fairly known for its sophisticated and fine designs. It is usually crafted in the form of repoussé, filigree and neillowork. Among the common traditional Malay items usually made of silver includes pillow ends, belt buckles, matt corners, stoppers for water vessels, kris sheaths, and tobacco boxes. The awan larat (cloud patterns) and kerawang (vegetal motives) are among the popular designs for Malay decorative silver pillow ends and tobacco boxes.[25]

Brasswork: The usage of brassware transcends a plethora of classical Malay social classes, being used by the members of nobility and commoners alike. The popularity of brassware is heavily contributed due to its durability, quality, and affordability to all. The brassware can be narrowed into two distinctions, yellow brass for functional items and white for decorative purposes. It is often meticulously hammered and craved with various decorative designs in religious and floral motives. The usage of brass, however, is also best known for tepak sirih, and for constructing certain musical instruments such as gongs for the classical Malay gamelan orchestra.

Pewterwork: Pewter is considered as relatively recent, with history only dated to the colonial era. Despite its recent history, Malaysia is very well known for its decorative pewter items and tableware. In fact, Malaysia was once the world’s largest tin producer and currently the largest manufacturer of pewter, so it is common for tourists to buy Malaysian pewter products as souvenirs.

Weaponry

.jpg.webp)

Blowpipe: A blowpipe is the simplest form of ranged weapon, consisting of a long narrow tube for shooting light projectiles such as darts. It is a traditional weapon for hunters of various indigenous tribes in both, west and east Malaysia, as well as a status symbol for many of them, similar to the kris to the Malays. In the past, craftsmen would take several months to make a blowpipe using traditional methods.

Kris: Kris is one of the most revered items of Malay weaponry. By the time of Malacca in the 15th century, the evolution of the Malay kris was perfected and possession of a kris came to be regarded as part-and-parcel of Malay culture, becoming a philosophical symbol, juxtaposition in prestige, craftsmanship, masculinity, and honour.[27][28][29] During this classical era, a Malay man was not seen without a kris outside of his house. The absence of a kris on a man was frowned upon, perceived as if he were parading naked to the public.

Other weaponry: There are also a plethora of other forms of weaponry in the Malay arsenal, all were nevertheless equally revered in a correlating manner as the kris. The Malays would classified the traditional weapons under seven different structures: Tuju ("Direct", the large and heavy artillery, including the Malay cannons of meriam, ekor lontong, lela and rentaka), Bidik ("A gun", a weapon with metal tube propelled by an ammunition, with the Malay forms of terakor and istingar), Setubuh ("A body", weapon in the similar dimension of a human body, referred to the Malay spears of tongkat panjang and lembing), Selengan ("An arm", a large saber from the length of the shoulders to the tips of the fingers, constituting the Malay saber of pedang and sundang), Setangan ("A hand", a sword with the diameter measured from the elbow to the three fingers, including badik panjang and tekpi), Sepegang ("A hold", smaller than the Setangan, a dagger with kris and badik in the category) and Segenggam ("A grab", the smallest in the category, the hand-sized blade, including lawi ayam, kerambit, kuku macan and kapak binjai).[30] Other items in the traditional Malay weaponry includes sumpit (blowpipe) and busur dan panah (bow and arrow), which are distinct from the seven class of armaments. Additionally, the Malays also would deploy zirah, a type of baju besi (armour) and perisai (shield) as defence mechanisms during the armed conflict.

Wood

This art form is mainly attributed to the abundance of timber in the archipelago and also by the skilfulness of the woodcarvers that have allowed the Malays and other indigenous people to practice woodcarving as a craft. The natural tropical settings where flora, fauna, and cosmic forces are abundant have inspired the motives to be depicted in abstract or styled form into the timber board.

Wood carving: Wood carving is a part of classical Malaysian arts. The Malay had traditionally adorned their monuments, boats, weapons, tombs, musical instruments, and utensils by motives of flora, calligraphy, geometry, and cosmic feature. The art is done by partially removing the wood using sharp tools and following specific patterns, composition, and orders. The art form, known as ukir in various Malaysian languages, is hailed as an act of devotion of the craftsmen to the creator and a gift to his fellowmen. With the coming of Islam, geometric and Islamic calligraphy became dominant in Malay wood carving.

A typical Malay traditional house or mosque would have been adorned with more than 20 carved components. The carving on the walls and the panels allow the air breeze to circulate effectively in and out of the building and can let the sunlight to light the interior of the structure. At the same time, the shadow cast by the panels would also create a shadow based on the motives of adding beauty to the floor. Thus, the carved components performed for both functional and aesthetic purposes.

On the other hand, traditional carvings of the Iban of Sarawak remains without outside influence. The ukir such as hornbill effigy carving, the terabai (shield), the engkeramba (ghost statue) are still being crafted. Another related category is engraving or drawing with paints on wooden planks, walls, or house posts by the Iban community. Even traditional coffins may be beautifully decorated using both carving and ukir-painting.

Boatbuilding: Terengganu is the centre of boat building in the Malay peninsula. The two Perahu Besar (big boat) of Terengganu, the pinas and the bedar are the result of cultural interchange between seafaring and trading civilisations. These boats are made of chengal wood, a heavy hardwood growing only on the Malay peninsula.[31] Among well-known Malaysian traditional boats are pinas and payang from Terengganu as well as lepa from east coast of Sabah. Today, this tradition is on the brink of extinction, with very few able craftsmen still practising this rare old building technique.

.jpg.webp)

Wood engraving: According to Orang Asli customs, deities take the form of carved wooden masks and idols. In a world rife with supernatural forces, these carved items also symbolise reverence to ancestral spirits. Various folk tales, myths, and legends of the olden days are transformed and passed down through these items. On special occasions, the dancers would wear masks to honour the spirits. Among hundreds of tribes in Malaysia, the Mah Meri of Selangor is the most well known for their traditional wood carving skills.

Besides the indigenous ethnic groups, wood is also engraved by the Chinese community in Malaysia. Besides deities, traditional signboards, carved from fine wood and gilded, are adorned in many Chinese traditional houses and cultural buildings thought out the country.

Musical instrument: Producing traditional Malaysian instruments such as rebana ubi, gambus and sape take high-quality wood and at least a few days of patience. Although it is mass-produced today, there are a few traditional instrument makers that are determined to hold onto this legacy. These instruments are often carved with local motifs, which also require a high level of craftsmanship.

Toy and game: Popular traditional Malaysian games such as gasing and congkak are usually made from wood. A great skill of craftsmanship is required to produce the most competitive gasing (top), some of which spin for two hours at a time.[32] On the other hand, the Malay variant of mancala board game, locally known as congkak is also made from wood. The most common congkak is shaped like an elongated boat, but some unusual shapes like a swan or mystical bird are also crafted in order to create a sense of authenticity to the craft.

Wooden furniture: The southern Malaysian city of Muar is considered the furniture hub of Malaysia with around 800 factories that account for about 55–60% of Malaysia's furniture export. The woods used for these furnitures are typically from tropical hardwood species that are known to be durable and can resist the attacks of the fungi, power-boots beetles, and termites. Some Malaysian wooden furnitures may also include traditional Malay wood carving and other decorative items.

Charcoal making: This art of making charcoal was brought in by the Japanese during occupation of Malaya. This art might not be as popular as before but it is still being produced and used for cooking in a lot of traditional Malaysian cuisines. The art of making charcoal is mainly concentrated in Kuala Sepetang, Larut and Matang, Perak. Although charcoal is considered as a controversial issue these days due to climate change, Matang, however, is recognised as a good model for sustainable mangrove forestry and conservation.

Ceramic

The term ceramic is derived from Greek, and literally refers to all forms of clay. However, the use of modern term extends its use to include inorganic non-metallic materials including earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. Until the 1950s, the most important traditionally was clay, which was used as pottery, brick, tile, and the like, along with cement and glass. Historically, ceramic items were hard, porous, and fragile. Nowadays, the art of ceramic includes pottery, crystal, glass, and marble.

Pottery: Malaysian pottery and ceramics were an essential part of the trade between Malaysia and its neighbours during feudalistic times, throughout Asia. Under the Malaysian culture, pottery is not solely witnessed as a mere household utensil. It is perceived as a work of art, a paradigm of talent, embroidered with aesthetic, legacy, perseverance, and religious devotion. The Malay earthenwares are usually unglazed, with the ornamental designs were carved when the pottery is semi-dried during its construction process.

According to several studies, the native Malay pottery industry has developed indigenously from the period of great antiquity and has since encapsulated a high-level of cultural sophistication. It also has been noted that the design features of the Malay pottery suggested the absence of foreign influence prior to the 19th century, a paradox considering the vast cultural contact between the Malays and the outside world.

There are four main areas of earthenware production in Malaysia; mambong in Kampung Mambong, Kuala Krai, Kelantan, labu Sayong in Sayong, Kuala Kangsar, Perak, terenang in Kampung Pasir Durian, Hulu Tembeling, Pahang and several places in Sarawak. Sarawak pottery has a very distinct and exotic look.

Porcelain: The Peranakans of Penang and Malacca are well-known for their artistic porcelain ware, also known as "Nyonyaware". Different sets were used for different occasions. These porcelain wares were originally commissioned and manufactured in China and exported for the wealthy Peranakan families in the British Straits Settlements. It is generally pastel base coloured than any other porcelain made in China such as bright yellow, green, pink, etc.

These porcelains are decorated in colourful overglaze Famille rose enamels, with motifs symbolising marital harmony and longevity. Due to its symbolic meaning in Peranakan culture, the phoenix and peony have a more prominent position in "Nyonyaware" more than that of other Chinese porcelain wares made for use in China itself.

There are four main designs for Malaysian porcelains; white with a pattern around the edges for everyday use, "Nyonya ware" for weddings or special occasions, "blue-and-white" for funeral occasions or serving the ancestors, and the street food dinnerware used in kopitiam and Chinese restaurants throughout the country.

Craft

Malaysia is fortunate to have natural resources that can contribute to the income and economy of the local communities. Forest products such as wood, bamboo, rattan, mengkuang, pandan, bemban, coconut shell and serdang leaves are used to create a variety of weaved and craft products. These skills and knowledge involving craftsmanship such as selecting materials and methods reflect the identities and socio-cultural development of these local communities.

Basketry: Malaysia’s main traditional craft is definitely the creation of various wicker handicrafts from the abundance of bamboo, rattan, and mengkuang in its forest. These wicker products were mainly weaved by women as a pastime hobby while the men were doing manual labour jobs like fishing, farming, or smithing. Examples include tudung saji (dish cover), tikar mengkuang (pandanus straw mat), ketapu (Iban woven hat) to rattan ball for sepak takraw, which continues to be popular not only as functional tools but also as ornaments to adorn houses with.

Kite is the most popular traditional Malaysian craft. Although both wau and layang-layang translated as kites in English, wau is specifically referring to the intricately designed Malaysian kite from the east coast of Malaysia. Wau-flying competitions take place across the country with judges awarding points for craftsmanship (wau kites are beautiful, colourful floral motif craft set on bamboo frames), sound (wau kites are designed to create a specific sound as they are buffeted about in the wind), and altitude (how high a wau kite can be flown).

Beadwork: Borneo has long been associated with products made of beads. Rungus of northern Sabah is known for their distinct and elaborate beaded accessories, ranging from necklaces, earrings, belts, and bangles. Colourful and beautiful, the beads are used in many traditional costumes, rituals, dances, and highly popular as souvenir items. Other than Rungus, beads also play an important role among the Orang Ulu tribes of Sarawak. The beads are made from various types of materials, namely wood, snail skin, stone, glass, bones, animal teeth and ceramics. Among the Orang Ulu tribes, the manufacturing techniques, colours and shapes differ with different amounts according to their respective beliefs and interpretations.

In the peninsula on the other hand, Nyonya women painstakingly stitch fine beads onto costumes, purses, handkerchiefs, and slippers creating high valued Nyonya beadwork. Historically, Nyonya women used a specific type of bead known as Peranakan cut beads, which are faceted glass beads imported from Europe. These beads were used to make the kasut manik (Peranakan beaded slippers) and other Peranakan artefacts such as wedding veils, handbags, belts, tapestries, and pouches. For the kasut manik, both smooth and faceted beads were used to form the pattern. Nowadays, the bead size commonly in use for Peranakan beadworks is bigger.

Paper: For centuries, Chinese lantern has been a part of Malaysian art scenes. Made with transparent paper and bamboo frame, the vibrant lanterns would be lit up during Chinese New Year and Lantern Festival in the yard of many houses, shops, business centres, shopping malls and even offices. These lanterns are not just for decorations during festive seasons. It is also used on certain occasions to welcome guests, to announce births, deaths, or even as danger warnings. Nowadays, uniquely colourful Malaysia-themed lanterns such as wau, aladdin lamps, goldfish and durian are also available.

Another common practice among Malaysians that use crafted papers is the burning of paper models of material items for the deceased. Malaysian Chinese still very strongly following this tradition, especially among the Taoists. These items also include a variety of high quality crafted paper model of houses, cars, treasure chests, clothes, or even daily utensils. It is also believed that the burning of these paper models served as an effective educational tool for the livings about the sense of total relinquishment at death.

Leaf: Woven with leaves, the art of leaf origami is a heritage of various ethnic groups in Malaysia. Woven leaves are transformed into attap roofing, cigarette, decorations and food wrappers. The only difference between the leaf origami and the modern Japanese origami is the use of various shapes of local leaves instead of the customary four-sided paper. The leaf origami designs are more complex and time-consuming.

Ketupat is a prime example of a traditional Malay woven food wrapper. It made from rice that has been wrapped in a woven palm leaf pouch and boiled. Despite the common triangular or diamond shapes, it can come in a wide variety of intricately woven designs ranging from star-like to animal-shaped. Nevertheless, ketupat is regarded as the symbol of celebration by various indigenous ethnic groups in the country, from Perlis to Sabah.

Flower: Symbolising spirituality, prosperity, and honour, flower garlands are an important part of worship and are believed to ward off bad spirits. Other than for offerings, gifts, or souvenirs, flower garlands, also locally known as bunga malai is draped around a person's neck to show respect or worn as hair ornaments in weddings among Malay, Thai and Indian communities in the country. These flower garlands are commonly being sold on the streets near temples especially by the Indian and Siamese communities.

Leather: Leatherworks are crafts made from animal raw hides and skins. The leathers are soaked in alkali solution, stretched and dried to prevent petrification as well as to soften them in order to make it more flexible. The material is commonly used for prop construction in traditional performing arts such as shadow puppet figures for wayang kulit as well as for traditional tribal costumes. Nowadays, leather is also used in making bags, wallets, clothes, shoes, etc.

Other

There are many other kinds of Malaysian art and crafts that cannot be classified in the aforementioned categories such as painting and calligraphy. These arts may also involve crafts made from various materials including banned materials.

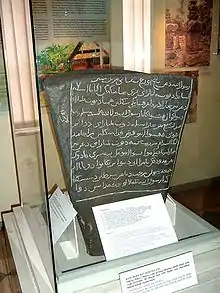

Calligraphy: Calligraphy is an art that prevails in Malaysia about 700 years ago as evidenced by the stone inscription encountered at Kuala Berang, Hulu Terengganu, Terengganu. The stone named Terengganu Inscription Stone possesses the first jawi calligraphy carving found in southeast Asia. Some of the common styles in Malaysia are the Islamic, Chinese and Indian calligraphy. This art of calligraphy is applied as building decorations such as interior ornamentations, decoration for mosques or temples, signages, books, currency, old manuscripts etc.

Painting: Painting as an art form is considered to be relatively new. It was only developed in the 20th century where it became the preferred artistic expression. Several design elements of traditional Malaysian paintings such as batik and tribal motifs are adapted to modern painting style to reflect the Malaysian identity. The most common paintings usually depict kampung and traditional life as well as the colonial landscape of many heritage sites in the country.

Ivory: In the past, ivory was the material of choice for making the handles of kris by the Malays. Elephant ivory is the most important source, but ivory from hornbills and other animals are used as well. Hornbill ivory is derived from the helmeted hornbill, a species of hornbill endemic to the Malay peninsula and Borneo. Indigenous peoples in the hornbill's range, such as the Kenyah and Kelabit of Sarawak, have long carved the casques as precious ornaments. It is also believed that the hornbill-ivory rings would change colour when near poisonous food.

Perfumery: Bunga rampai is a mixture of several types of selected flowers and pandan leaves that are finely sliced and mixed with perfume. It gives special therapy to the ceremony held and is very well placed in the bridal room as an important part of Malay customs and traditions. Besides bunga rampai, the Malays also use flowers during the ritual bath known as mandi bunga. This practice is usually done either to perfume and refresh the body, enhance the complexion and beautify the skin. In fact, this ritual bath is synonymous with weddings or as an effort to attract the man's attention.

Kolam: Kolam is a form of drawing that is drawn by using rice flour, chalk, chalk powder, or rock powder, often using naturally or synthetically coloured powders. This colourful artwork is usually found during the month of Deepavali, on the floors of shopping malls and public places in the country. It is considered to be the distinctive art form in celebration of this occasion and a symbol of the celebration of the Indian community in Malaysia.

Folk costume

Traditional Malaysian costume and textile has been continuously morphed since the time of antiquity. Historically, the ancient Malays were chronicled to incorporate various natural materials as a vital source for fabrics, clothing, and attire. The common era, however, witnessing the early arrivals of the merchants from east and west to the harbours of the Malay archipelago, together they bought new luxurious items, including fine cotton and silks. The garments subsequently become a source of high Malay fashion and acquired a cultural role as the binding identity in the archipelago, especially in the peninsula, and the coastal areas of Borneo.[33]

Costume: Traditional Malaysian costume varies between different regions, but the most profound traditional dress in modern-day are baju kurung and baju kebaya (for women) and baju Melayu (for men), which both recognised as the national dress for Malaysia. Since Malaysia comprises hundreds of different ethnic groups, each culture has its own traditional and religious articles of clothing all of which are gender-specific and may be adapted to local influences and conditions. The clothing of different tribes also differs with different amounts, with tribes in close proximity having similar clothing.

Headgear: Man’s headgears in Malaysia can be categorized into three categories: tengkolok, which is a piece of cloth tied around the head; songkok or kopiah, a type of cap made from velvet worn by Muslims; and semutar or serban, which resembles a turban and is a typical headdress in the middle east. Different headgears are used on different occasions. This was especially so in the old days when different headgears were worn, which more often than not reflect the individual's stations in life, both for formal and informal occasions. Women, on the other hand, would sometimes wear tudong or selendang.

Textile: In Malaysian culture, clothes and textiles are revered as symbols of beauty, power and status. The Malay handloom industry can be traced its origin since the 13th century when the eastern trade route flourished under Song dynasty. Mention of locally made textiles as well as the predominance of weaving in Malay peninsula was made in various Chinese and Arab accounts.[34] There are four main areas of textiles production in Malaysia; songket, batik, limar, pelangi, and tenun in Kelantan, Terengganu and Pahang; telepok, tekat, and sulam in Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan and Malacca; pua kumbu, songket and keringkam in Sarawak; as well as various woven and non-woven tribal clothes in Sabah.

_(14598282467).jpg.webp)

Tattoo: The Dayaks of Borneo are not for their traditional method of tattooing, a hand tapping style method using two sticks. According to the Dayak culture, different motifs are used for different parts of the body, where the purpose of the tattoos is to protect the tattoo bearer or to signify certain events in their life. One of the most important motifs of Iban tattoo includes bungai terung (Bornean eggplant flower), which is the first tattoo an Iban individual would receive to mark the Iban tradition known as bejalai. Bejalai is a journey of knowledge and wisdom, where an individual would leave their longhouse to experience the world.

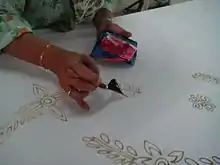

Henna: Henna is a traditional temporary dye used to adorn the body, especially during weddings. In Malay culture, the malam berinai will be held the night before the wedding, where the bride will be adorned with elaborate henna patterns on her fingers and toes. This aesthetic art form is said to bring luck, beauty, and happiness to the bearer. The Malay wedding ceremony is considered to be "incomplete" if the bride does not adorn henna on her fingers. Even though the art originated from India, the use of henna on fingers and toes are considered a part of indigenous Malay culture.

Footwear: Terompah (wooden clogs) were a common sight in many Malaysian households in the past. Nowadays, there are only a handful of clog-makers left, mainly concentrated in cities like Penang and Malacca. Compare to the terompah, the Nyonya colourful kasut maniks are highly valued in Malaysia, and can cost thousands of ringgit. Kasut maniks are intricate and finely stitched, a testimony to the fine workmanship of yesteryears. The intricacy and fine workmanship of a pair of the beaded slipper is also a hallmark of highly accomplished Peranakan Nyonya as well as one of the requirements to get married in the past.

Jewellery: Traditional Malaysian pieces of jewellery used with traditional dresses reflect the rich in symbolism and design of the local craftsmen. In the contemporary era, Malaysian jewellery has involved and mainly found in the form of anklets, bracelets, rings, necklaces, pendants, and earrings. Traditionally, Malay craftsmen would mould gold, silver, and brass to create these beautiful accessories while in east Malaysia, wood, snail skin, bones, animal teeth and leather were used to the same effect. With modern technology, materials like pearls and pewter are also being used.

Cuisine

Malaysian cuisine consists of cooking traditions and practices found in Malaysia and reflects the multi-ethnic makeup of its population. The vast majority of Malaysia's population can roughly be divided into three major ethnic groups: Malays, Chinese, and Indians. The remainder consists of the indigenous peoples of Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo, the Orang Asli of Peninsular Malaysia, the Peranakan and Eurasian creole communities, as well as a significant number of foreign workers and expatriates.

Different Malaysian regions are all known for their unique or signature dishes— Terengganu and Kelantan for their east coast nasi dagang, nasi kerabu and keropok lekor; Pahang and Perak for its durian-based cuisines, including gulai and pais tempoyak; Penang, Kedah and Perlis for their northern-style asam laksa, char kway teow, and rojak; Negeri Sembilan for its lemak-based dishes, rendang and lemang; Malacca for their peranakan cuisines and eurasian cuisines; Selangor and Johor for its lontong, nasi ambeng, and bak kut teh; Sabah for its hinava, latok and tiyula itum; Sarawak for its ayam pansuh, laksa Sarawak and kek lapis Sarawak.

Nasi kerabu served with various herbs, fish meat-stuffed pepper, salted egg, fried fish, keropok and marinated chicken.

Nasi kerabu served with various herbs, fish meat-stuffed pepper, salted egg, fried fish, keropok and marinated chicken. A plate of Penang's char kway teow served on a banana leaf, one of the national favourites of Malaysia.

A plate of Penang's char kway teow served on a banana leaf, one of the national favourites of Malaysia. A plate of fish head curry, a uniquely Malaysian dish, with mixed Indian, Chinese and Malay origins.

A plate of fish head curry, a uniquely Malaysian dish, with mixed Indian, Chinese and Malay origins.

A colourful kek lapis Sarawak containing raisins served during special occasions in Sarawak.

A colourful kek lapis Sarawak containing raisins served during special occasions in Sarawak.

Contemporary art

Nowadays, besides working with traditional material such as wood, ceramic and forest products, the younger generation of Malaysian artists have become very active in involving different forms of arts, such as animation, photography, paintings and street art with many of them attaining international recognition for their artworks and exhibitions worldwide.

Animation: Animation in Malaysia has origins in the puppetry style of wayang kulit, wherein the characters are controlled by the puppeteer, locally known as tok dalang. Since 2000, the Malaysian animation industry has gone far globally when Multimedia Development Corporation (MDeC) was launched by the government a few years earlier in an effort to transition Malaysia from a manufacturing economy to one based more in information and knowledge. Since then, many Malaysian animation companies marketed their works globally. Their animation has succeeded in promoting Malaysia globally by creating content that was based on Malaysian culture but with universal values. Several Malaysian animation films and series that have hit global market are The Kampung Boy, Upin & Ipin, BoBoiBoy and Ejen Ali. Among these, it is said that The Kampung Boy, based on the characters of international-known cartoonist, Lat, is seen as the best animation that portrays Malaysian arts.

Street art: Given the various benefits and high return on investment, street art provides to local businesses, schools, neighbourhoods, and communities, the street art scene has blossomed in many parts of the country. In Penang, art exhibitions are held at the city's numerous cultural centres, such as the Hin Bus Depot to celebrate and preserve the local arts, culture and heritage.[36] Aside from wall art, several wrought iron caricatures, each depicting a unique aspect of George Town's history and culture, have been installed throughout the city.[37]

In 2012, as part of the annual George Town Festival, Lithuanian artist Ernest Zacharevic created a series of wall murals depicting local Malaysian culture, inhabitants and lifestyles.[38] These murals now stand as celebrated cultural landmarks of the historic UNESCO World Heritage Site, with Children on a Bicycle becoming one of the most photographed spots in the city.[39] Besides, artistic performance, such as dance, music and theatre, as well as animation, photography and painting, have also been included in the festival.

See also

References

- "For Sale – CountryHeights". The Art of Living Show. Mar 22, 2011 – via YouTube.

- O'Reilly 2007, p. 42.

- Jamil Abu Bakar 2002, p. 59.

- Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi 2005, p. 19.

- Cavendish 2007, p. 1219

- Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi 2005, p. 24.

- Ahmad, A. Ghafar. "Malay Vernacular Architecture". Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Noor & Khoo 2003, p. 47.

- Moore 1998, p. 48.

- Cavendish 2007, p. 1220.

- "Bermukun, adat Melayu Sarawak yang tidak lapuk ditelan zaman". January 3, 2018.

- "Belotah".

- Rahmah Bujang (1987). Boria: A Form of Malay Theatre. Institute of Southeast Asian. ISBN 99-719-8858-5.

- "Cempuling".

- Srinivasa 2003, p. 296.

- Ghulam Sarwar Yousof 1997, p. 3.

- Matusky 1993, pp. 8–11.

- Wazir-Jahan Begum Karim, ed. (1990). Emotions of culture: a Malay perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 01-958-8931-2.

- Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof (2015). One Hundred and One Things Malay. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 978-14-828-5534-0.

- Zinitulniza Abdul Kadir (2014). MEK MULUNG: Kesenian Perantaraan Manusia dan Kuasa Ghaib Warisan Kedah Tua. ITBM. ISBN 978-96-743-0772-1.

- James 1994, p. 73.

- Alexander 2006, p. 225.

- Abd. Rahman Ismail 2008, p. 188.

- Tim Bunnell, Lisa Barbara Welch Drummond & Kong-Chong Ho (2002). Critical reflections on cities in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Time Media Private Limited. p. 201. ISBN 981-210-192-6.

- "Malaysia Handicrafts ~ Gold Silver & Brass". Go2Travelmalaysia.com.

- Karyaneka. "Metal Work". Syarikat Pemasaran Karyaneka Sdn. Bhd. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Niza 2016.

- Zakaria 2016.

- Angahsunan 2017.

- Kerawang Merah (2017), 7 Kelas Senjata Alam Melayu

- 100 Malaysian Timbers, published by Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1986, p16/17

- Alexander 2006, p. 51

- Hassan 2016.

- Maznah Mohammad 1996, p. 19.

- "George Town Festival's secret to success? Penang first, tourism second". Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- Nicole Chang (2017). "Hin Bus Depot – Derelict No More". Penang Monthly. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- "Street art in Penang". Time Out Penang. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- Lim, Serene (24 April 2015). "The good, bad and ugly of street artist Ernest Zacharevic's murals". Today. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Winnie Yeoh (3 November 2013). "The Guardian picks Little Children". The Star.

Bibliography

- Abd. Rahman Ismail (2008). Seni Silat Melayu: Sejarah, Perkembangan dan Budaya. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. ISBN 978-983-62-9934-5.

- Alexander, James (2006). Malaysia Brunei & Singapore. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-86011-309-3.

- Angahsunan (July 16, 2017). "Pusaka, Rahsia Dan Dzat Keris". The Patriots. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Cavendish, Marshall (2007), World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, New York: Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3

- Ghulam Sarwar Yousof (1997), The Malay Shadow Play: An Introduction, The Asian Centre, ISBN 978-983-9499-02-5

- Hassan, Hanisa (2016). "A Study on the Development of Baju Kurung Design in the Context of Cultural Changes in Modern Malaysia" (PDF). Wacana Seni Journal of Arts Discourse. Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. 15: 63–94. doi:10.21315/ws2016.15.3. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- James, Michael (1994). "Black Belt". Black Belt. Buyer's Guide. Rainbow Publications. ISSN 0277-3066.

- Jamil Abu Bakar (2002). A design guide of public parks in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit UTM. ISBN 978-983-52-0274-2.

- Matusky, Patricia Ann (1993). Malaysian shadow play and music: continuity of an oral tradition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-967-65-3048-6.

- Maznah Mohammad (1996), The Malay handloom weavers: a study of the rise and decline of traditional manufacture, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-981-3016-99-6

- Mohamad Tajuddin Haji Mohamad Rasdi (2005). The architectural heritage of the Malay world: the traditional houses. Skudai, Johor Darul Ta'zim: Penerbit Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. ISBN 978-983-52-0357-2.

- Moore, Wendy (1998). West Malaysia and Singapore. Singapore: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. ISBN 978-962-593-179-1.

- Niza, Syefiri Moniz Mohd. (10 June 2016). "Keris masih simbol paling penting". Utusan online. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Noor, Farish Ahmad; Khoo, Eddin (2003). Spirit of wood: the art of Malay woodcarving : works by master carvers from Kelantan, Terengganu, and Pattani. Singapore: Periplus Editions. ISBN 978-0-7946-0103-4.

- O'Reilly, Dougald J. W. (2007), Early civilizations of Southeast Asia, Rowman Altamira Press, ISBN 978-0-7591-0278-1

- Srinivasa, Kodaganallur Ramaswami (2003), Asian variations in Ramayana, Singapore: Sahitya Academy, ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3

- Zakaria, Faizal Izzani (2016-09-03). "Keris jiwa Melayu dan Nusantara". Utusan online. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.