Gan Chinese

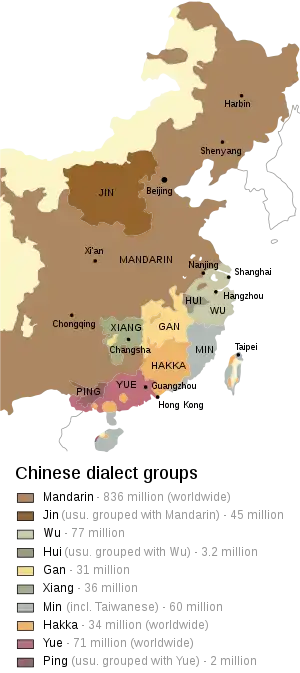

Gan, Gann[2] or Kan is a group of Sinitic languages spoken natively by many people in the Jiangxi province of China, as well as significant populations in surrounding regions such as Hunan, Hubei, Anhui, and Fujian. Gan is a member of the Sinitic languages of the Sino-Tibetan language family, and Hakka is the closest Chinese variety to Gan in terms of phonetics.

| Gan | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gann | |||||||||||||||

| 贛語/赣语 Gon ua | |||||||||||||||

Gan ua (Gan) written in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||

| Native to | China | ||||||||||||||

| Region | central and northern Jiangxi, eastern Hunan, eastern Hubei, southern Anhui, northwest Fujian | ||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | Gan people | ||||||||||||||

Native speakers | 22 million (2018)[1] | ||||||||||||||

Early forms | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese character Pha̍k-oa-chhi | |||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 | gan | ||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | ganc1239 | ||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-f | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 贛語 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赣语 | ||||||||||||||

| Gan | Gon ua | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Jiangxi dialect | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 江西話 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 江西话 | ||||||||||||||

| Gan | Kongsi ua | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Different dialects of Gan exist; the Nanchang dialect is usually taken as representative.

Classification

Like all other varieties of Chinese, there is a large amount of mutual unintelligibility between Gan Chinese and other varieties. Within the variation of Chinese dialects, Gan has more similarities with Mandarin than with Yue or Min. However, Gan clusters more with Xiang than Mandarin.

Name

- Gan: the most common name. Also spelled Gann to reflect the falling tone of the name in Mandarin. Scholars in mainland China use Gan or Gan dialect.

- Jiāngxī huà ("Jiangxi language") is commonly used in Chinese, but since the borders of the language do not follow the borders of the province, this name is not geographically exact.

- Xi ("right-river language"): an ancient name, now seldom used, arising from the fact that most Gan speakers live south of the Yangtze River, beyond the right-hand bank when traveling downstream.

Region

Most Gan speakers live in the middle and lower reaches of the Gan River, the drainage area of the Fu River, and the region of Poyang Lake. There are also many Gan speakers living in eastern Hunan, eastern Hubei, southern Anhui, northwest Fujian, etc.

According to the Diagram of Divisions in the People's Republic of China,[3] Gan is spoken by approximately 48,000,000 people: 29,000,000 in Jiangxi,[4] 4,500,000 in Anhui,[5] 5,300,000 in Hubei,[6] 9,000,000 in Hunan,[7] and 270,000 in Fujian.[8]

History

Antiquity

During the Qin Dynasty (221 BC), a large number of troops were sent to southern China in order to conquer the Baiyue territories in Fujian and Guangdong, as a result, numerous Han Chinese emigrated to Jiangxi in the years following. In the early years of the Han Dynasty (202 BC), Nanchang was established as the capital of the Yuzhang Commandery (豫章郡) (this name stems from the original name of Gan River), along with the 18 counties (縣) of Jiangxi Province. The population of the Yuzhang Commandery increased from 350,000 (in AD 2) to 1,670,000 (by AD 140); it ranked fourth in population among the more than 100 contemporary commanderies of China. As the largest commandery of Yangzhou, Yuzhang accounted for two fifths of the population and Gan gradually took shape during this period.

Middle ages

As a result of continuous warfare in the region of central China, the first large-scale emigration in the history of China took place. Large numbers of people in central China relocated to southern China in order to escape the bloodshed and at this time, Jiangxi played a role as a transfer station. Also, during this period, ancient Gan began to be exposed to the northern Mandarin dialects. After centuries of rule by the Southern Dynasties, Gan still retained many original characteristics despite having absorbed some elements of Mandarin. Up until the Tang Dynasty, there was little difference between old Gan and the contemporary Gan of that era. Beginning in the Five Dynasties period, however, inhabitants in the central and northern parts of Jiangxi Province began to migrate to eastern Hunan, eastern Hubei, southern Anhui and northwest Fujian. During this period, following hundreds of years of migration, Gan spread to its current areas of distribution.

Late traditional period

Mandarin Chinese evolved into a standard language based on Beijing Mandarin, owing largely to political factors. At the same time, the differences between Gan and Mandarin continued to become more pronounced. However, because Jiangxi borders on Jianghuai, a Guanhua, Xiang, and Hakka speaking region, Gan proper has also been influenced by these surrounding varieties, especially in its border regions.

Modern times

After 1949, as a "dialect" in Mainland China, Gan faced a critical period. The impact of Mandarin is quite evident today as a result of official governmental language campaigns. Currently, many youths are unable to master Gan expressions, and some are no longer able to speak Gan at all.

Recently, however, as a result of increased interest in protecting the local language, Gan now has begun to appear in various regional media, and there are also newscasts and television programs broadcast in Gan Chinese.

Languages and dialects

There are significant differences within the Gan-speaking region, and Gan constitutes more languages than listed here. For example, in Anfu county, which was categorized as Ji-Cha, there are two main varieties, called Nanxiang Hua (Southern region) and Baixiang Hua (Northern region). People from one region cannot even understand people from the other region if they were not well educated or exposed to the other.

The Language Atlas of China (1987) divides Gan into nine groups:[9][10]

| Subgroup | Representative | Provinces | Cities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changdu 昌都片 | Nanchang dialect | northwestern Jiangxi | Nanchang City, Nangchang, Xinjian, Anyi, Yongxiu, Xiushui*, De'an, Xingzi, Duchang, Hukou, Gao'an*, Fengxin*, Jing'an*, Wuning*, Tonggu* |

| northeastern Hunan | Pingjiang | ||

| Yiliu 宜浏片 / 宜瀏片 | Yichun dialect | central and western Jiangxi | Yichun City, Yichun, Yifeng*, Shanggao, Qingjiang, Xingan, Xinyu City, Fen yi, Pingxiang City, Fengcheng, Wanzai |

| eastern Hunan | Liuyang*, Liling | ||

| Jicha 吉茶片 | Ji'an dialect | central and southern Jiangxi | Ji'an City, Ji'an*, Jishui, Xiajiang, Taihe*, Yongfeng*, Anfu, Lianhua, Yongxin*, Ninggang*, Jianggangshan* Wan'an, Suichuan* |

| eastern Hunan | Youxian*, Chaling*, Linxian | ||

| Fuguang 抚广片 / 撫廣片 | Fuzhou dialect (撫州, not to be confused with 福州) | central and eastern Jiangxi | Fuzhou City, Linchuan, Chongren, Yihuang, Le'an, Nancheng, Lichuan, Zixi, Jinxi, Dongxiang, Jinxian, Nanfeng, Guangchang* |

| southwestern Fujian | Jianning, Taining | ||

| Yingyi 鹰弋片 | Yingtan dialect | northeastern Jiangxi | Yingtan City, Guixi, Yujiang, Wannian, Leping, Jingdezhen*, Yugan, Poyang, Pengze, Hengfeng, Yiyang, Chuanshan |

| Datong 大通片 | Daye dialect | southeastern Hubei | Daye, Xianning City, Jiangyu, Puxin, Chongyang, Tongcheng, Tongshan, Yangxin, Jianli* |

| eastern Hunan | Linxiang*, Yueyang*, Huarong | ||

| Leizi 耒资片 / 耒資片 | Leiyang dialect | eastern Hunan | Leiyang, Changning, Anren, Yongxing, Zixing City |

| Dongsui 洞绥片 / 洞綏片 | Dongkou dialect | southwestern Hunan | Dongkou*, Suining*, Longhui* |

| Huaiyue 怀岳片 / 懷嶽片 | Huaining dialect | southwestern Anhui | Huaining, Yuexi, Qianshan, Taihu, Wangjiang*, Susong*, Dongzhi*, Shitai*, Guichi* |

Cities marked with * are partly Gan-speaking.

Phonology

Grammar

In Gan, there are nine principal grammatical aspects or "tenses" – initial (起始), progressive (進行), experimental (嘗試), durative (持續), processive (經歷), continuative (繼續), repeating (重行), perfect (已然), and complete (完成).

The grammar of Gan is similar to southern Chinese varieties. The sequence subject–verb–object is most typical, but subject–object–verb or the passive voice (with the sequence object–subject–verb) is possible with particles. Take a simple sentence for example: "I hold you". The words involved are: ngo ("I" or "me"), tsot dok ("to hold"), ň ("you").

- Subject–verb–object (typical sequence): The sentence in the typical sequence would be: ngo tsot dok ň. ("I hold you.")

- Subject–lat–object–verb: Another sentence of roughly equivalent meaning is ngo lat ň tsot dok, with the slight connotation of "I take you and hold" or "I get to you and hold."

- Object–den–subject–verb (the passive voice): Then, ň den ngo tsot dok means the same thing but in the passive voice, with the connotation of "You allow yourself to be held by me" or "You make yourself available for my holding."

Vocabulary

In Gan, there are a number of archaic words and expressions originally found in ancient Chinese, and which are now seldom or no longer used in Mandarin. For example, the noun "clothes" in Gan is "衣裳" while "衣服" in Mandarin, the verb "sleep" in Gan is "睏覺" while "睡覺" in Mandarin. Also, to describe something dirty, Gan speakers use "下里巴人", which is a reference to a song from the Chu region dating to China's Spring and Autumn period.

Additionally, there are numerous interjections in Gan (e.g. 哈、噻、啵), which can largely strengthen sentences, and better express different feelings.

Writing system

Gan is written with Chinese characters, though it does not have a strong written tradition. There are also some romanization schemes, but none are widely used. When writing, Gan speakers usually use written vernacular Chinese, which is used by all Chinese speakers.[11]

References

- Gan Chinese at Ethnologue (23nd ed., 2020)

- The double nn represents the falling tone in Mandarin

- 《中華人民共和國行政區劃簡冊》 (in Chinese). 2004.

- 江西人口状况. 泛珠三角合作信息网 (in Chinese). 9 September 2005.

- 安徽人口控制:14年少生800万人. Xinhua (in Chinese). Shanghai. 7 January 2005. Archived from the original on 19 September 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- http://www.chinapop.gov.cn/rkkx/gdkx/t20040326_8746.htm Archived May 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- http://news.rednet.com.cn/Articles/2005/01/651873.HTM Archived August 29, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.chinapop.gov.cn/rkkx/gdkx/t20050107_18667.htm Archived April 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006). Introduction to Chinese Dialectology. LINCOM Europa. p. 148. ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010). Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects". Walter de Gruyter. p. 70. ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- "Chinese, Gan". ethnologue.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Chen Changyi. Summary of Gan.

- Chen Changyi. Chorography of languages in Jiangxi.

- Li Rulong. Investigation of Gan-Hakka.

- Xiong Zhenghui. Dictionary of Nanchang Dialect.

- Yan Sen. Division of languages in Jiangxi.

- Yan Sen. Summary of modern Chinese·Gan.

Further reading

- Coblin, W. South (2015). A Study of Comparative Gàn (PDF). Taiwan: Academia Sinica Institute of Linguistics. ISBN 978-986-04-5926-5.

- Li, Xuping. 2018. A Grammar of Gan Chinese, De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, ISBN 978-1501515798.

- Miyake, Marc. 2012. Departing the departing tone: more tones in Gan dialects.

- Miyake, Marc. 2012. Voiced-high Gan dialects?

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gan. |

| Look up Appendix:Gan Swadesh list in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Gan language edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |