Polisario Front

The Polisario Front, Frente Polisario, FRELISARIO or simply POLISARIO, from the Spanish abbreviation of Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro (Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Río de Oro, Arabic: الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير ساقية الحمراء و وادي الذهب Al-Jabhat Al-Sha'abiyah Li-Tahrir Saqiya Al-Hamra'a wa Wadi Al-Dhahab, French: Front populaire de Libération de la Seguia el Hamra et de la Rivière d'or), is a rebel national liberation movement by the Sahrawi people (of the Sahara) aiming to take control of the Western Sahara, which had been controlled by Spain, Mauritania, and as of 2021 was under the rule of Morocco. It is a consultative member of the Socialist International.[1]

Polisario Front Frente Polisario جبهة البوليساريو Jabhat al-Bōlīsāryū | |

|---|---|

| |

| Secretary-General | Brahim Ghali |

| Founder | El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed |

| Founded | 10 May 1973 |

| Headquarters | Sahrawi refugee camps, Tindouf Province, Algeria |

| Youth wing | Sahrawi Youth Union |

| Women's wing | National Union of Sahrawi Women |

| Trade union affiliation | Sahrawi Trade Union |

| Ideology | Sahrawi nationalism Social democracy Historical: Democratic socialism |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| International affiliation | Progressive Alliance Socialist International (consultative) |

| Colors | Red, black, white, and green (Pan-Arab colors) |

| Sahrawi National Council | 53 / 53 |

| Pan-African Parliament | 5 / 5 (Sahrawi Republic seats) |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

The United Nations considers the Polisario Front to be the legitimate representative of the Sahrawi people and maintains that the Sahrawis have a right to self-determination.[2][3] The Polisario Front is outlawed in the parts of Western Sahara under Moroccan control, and it is illegal to raise its party flag (often called the Sahrawi flag) there.[4]

History

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the SADR |

Beginnings

In 1971 a group of young Moroccan students in the universities of Morocco began organizing what came to be known as The Embryonic Movement for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Rio de Oro.[5]

After attempting in vain to gain backing from several Arab governments, including both Algeria and Morocco, but only drawing faint notices of support from Libya and Mauritania, the movement eventually relocated to Spanish-controlled Spanish Sahara to start an armed rebellion.

The Polisario Front was formally constituted on 10 May 1973 at Ain Bentili by several Sahrawi university students, survivors of the 1968 massacres at Zouerate and some Sahrawi men who had served in the Spanish Army.[6] They called themselves the Constituent Congress of the Polisario Front.[6]

Its first Secretary General was El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed. On 20 May, the new organization attacked El-Khanga,[6] where there was a Spanish post manned by a team of Tropas Nomadas (Sahrawi-staffed auxiliary forces), which was overrun and rifles seized. Polisario then gradually gained control over large swaths of desert countryside, and its power grew from early 1975 when the Tropas Nomadas began deserting to the Polisario, bringing weapons and training with them. At this point, Polisario's manpower included perhaps 800 men and women, but they were suspected of being backed by a much larger network of supporters.

A UN visiting mission, headed by Simeon Aké, that was conducted in June 1975 concluded that Sahrawi support for independence (as opposed to Spanish rule or integration with a neighbouring country) amounted to an "overwhelming consensus" and that the Polisario Front was the most powerful political force in the country.[7] With Algeria's help, Polisario set up headquarters in Tindouf.[8]

Withdrawal of Spain

| Part of a series on the |

| Western Sahara conflict |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Regions |

| Politics |

| Clashes |

| Issues |

| Peace process |

After Moroccan pressures through the Green March of 6 November and the Royal Moroccan Army's previous invasion of eastern Saguia el-Hamra of 31 October, Spain entered negotiations that led to the signing of the Madrid Accords whereby Spain ceded Spanish Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania; in 1976 Morocco took over Saguia El Hamra and Mauritania took control of Río de Oro. The Polisario Front proclaimed the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) on 27 February 1976, and waged a guerrilla war against both Morocco and Mauritania. The International Court of Justice at The Hague had issued its verdict on the former Spanish colony just weeks before, which each party interpreted as confirming its right to the disputed territory.

The Polisario kept up the guerrilla war while they simultaneously had to help guard the columns of Sahrawi refugees fleeing, but after the air bombings by the Royal Moroccan Air Force on improvised Sahrawi refugee camps in Umm Dreiga, Tifariti, Guelta Zemmur and Amgala, the Front had to relocate the refugees to Tindouf (western region of Algeria). For the next two years the movement grew tremendously as Sahrawi refugees continued flocking to the camps and Algeria and Libya supplied arms and funding. Within months, its army had expanded to several thousand armed fighters, camels were replaced by modern jeeps (most of them were Spanish Land Rover Santana jeeps, captured from Moroccan soldiers), and 19th-century muskets were replaced by assault rifles. The reorganized army was able to inflict severe damage through guerrilla-style hit-and-run attacks against opposing forces in Western Sahara and in Morocco and Mauritania proper.

Withdrawal of Mauritania

A comprehensive peace treaty was signed on 5 August 1979, in which the new Mauritanian government recognized Sahrawi rights to Western Sahara and relinquished its own claims. Mauritania withdrew all its forces, and later formally recognized the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, causing a massive rupture in relations with Morocco. The area of Western Sahara evacuated by Mauritania (Tiris al-Gharbiya, roughly corresponding to the southern half of Río de Oro), was annexed by Morocco in August 1979.[9]

Moroccan wall stalemates the war

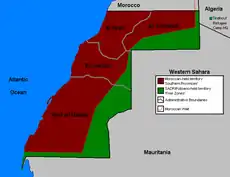

From the mid-1980s Morocco largely managed to keep Polisario troops off by building a huge berm or sand wall (the Moroccan Wall), staffed by an army, enclosing within it the economically useful parts of Western Sahara (Bou Craa, El-Aaiun, Smara, etc.) This stalemated the war, with no side able to achieve decisive gains, but artillery strikes and sniping attacks by the Polisario continued, and Morocco was economically and politically strained by the war. Today Polisario controls the part of the Western Sahara on the east of the Moroccan Wall, comprising about a third of the territory, but this area is economically useless, heavily mined, and almost uninhabited.

Ceasefire and the referendum process

A ceasefire between the Polisario Front and Morocco, monitored by MINURSO (UN), has been in effect since 6 September 1991, on the promise of a referendum on independence the following year. However, the referendum stalled over disagreements on voter rights. Numerous attempts to restart the process (most significantly the launching of the 2003 Baker Plan) seem to have failed.

In April 2007, the government of Morocco suggested that a self-governing entity, through the Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS), should govern the territory with some degree of autonomy for Western Sahara. The project was presented to the United Nations Security Council in mid-April 2007, and quickly gained French and US support. Polisario had handed in its own proposal the day before, which insisted on the previously agreed referendum, but allowed for negotiating the status of Moroccans now living in the territory should the outcome of a referendum be in favor of independence. This led to the negotiations process known as the Manhasset negotiations.

Four rounds were held in 2007 and 2008; no progress was made, however, as both parties refused to compromise about what they considered core sovereignty issues. Polisario agreed to add autonomy as per the Moroccan proposal to a referendum ballot, but refused to relinquish the concept of an independence referendum itself, as agreed in 1991 and 1997. Morocco, in its turn, insisted on only negotiating the terms of autonomy offered, but refused to consider an option of independence on the ballot.

The 30-year cease-fire between Morocco and Polisario Front was broken in November 2020 as the government tried to open a road in the Guerguerat buffer zone near the border with Mauritania.[10]

Political ideology

The Polisario is first and foremost a nationalist organization, whose main goal is the independence of Western Sahara. It has stated that ideological disputes should be left for a future democratic Western Sahara to deal with. It views itself as a "front" encompassing all political trends in Sahrawi society, and not as a political party. As a consequence, there is no party program. However, the Sahrawi republic's constitution gives a hint of the movement's ideological context: in the early 1970s, Polisario adopted a vaguely socialist rhetoric, in line with most national liberation movements of the time, but this was eventually abandoned in favor of a non-politicized Sahrawi nationalism. By the late 1970s, references to socialism in the republic's constitution were removed, and by 1991, the Polisario was explicitly pro-free-market.

The Polisario has stated that it will, when Sahrawi self-determination has been achieved, either function as a party within the context of a multi-party system, or be completely disbanded. This is to be decided by a Polisario Front congress upon the achievement of Western Sahara's independence.

Attitudes to armed struggle

The Polisario Front has denounced terrorism and attacks against civilians,[11] and sent condolences to Morocco after the 2003 Casablanca bombings. It describes its struggle as a "clean war of national liberation". Since 1989, when the ceasefire was first concluded, the movement has stated it will pursue its goal of Western Sahara's independence by peaceful means as long as Morocco complies with the ceasefire conditions, which include arranging a referendum on independence, while reserving the right to resume armed struggle if terms are objectively breached, for example, if the referendum is not conducted. Mohamed Abdelaziz has repeatedly stated that the Moroccan withdrawal from the 1991 Settlement Plan and refusal to sign the 2003 Baker Plan would logically lead to war from its perspective if the international community does not step in.[12] In contrast, Polisario-Mauritanian relations following a peace treaty in 1979 and the recognition of the SADR by Mauritania in 1984, with the latter's retreat from Western Sahara, have been quiet and generally neutral without reports of armed clashes from either side.

The series of protests and riots in 2005 by Sahrawis in "the occupied territories" received strong vocal support from Polisario as a new pressure point on Morocco. Abdelaziz characterized them as a substitute path for the armed struggle, and indicated that if peaceful protest was squashed, in its view, without a referendum forthcoming, its armed forces would intervene.

Relations with Algeria

Algeria has shown an unconditional support for the Polisario Front since 1975, delivering arms, training, financial aid, and food, without interruption for more than 30 years. In 1976, Algeria called the Moroccan takeover of Western Sahara a "'slow murderous' invasion against spirited fighting by Sahara guerrillas.[13] At the level of international relations, Algeria appears as a main actor and negotiator in opposition to Morocco since the beginning of the Western Sahara conflict.

Structure

Organizational background

Until 1991, the Polisario Front's structure was much different from the present one. It was, despite a few changes, inherited from the before 1975, when the Polisario Front functioned as a small, tightly-knit guerrilla movement, with a few hundred members. Consequently, it made few attempts at a division of powers, instead concentrating most of the decision-making power in the top echelons of Polisario for maximum battlefield efficiency. This meant that most power rested in the hands of the Secretary General and a nine-man executive committee, elected at congresses and with different military and political responsibilities. A 21-man Politburo would further check decisions and connect the movement with its affiliated "mass organizations", UGTSARIO, UJSARIO and UNMS (see below).

But after the movement took on the role as a state-in-waiting in 1975, based in the refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, this structure proved incapable of dealing with its vastly expanded responsibilities. As a consequence, the old military structure was wedded to the new grass-roots refugee camp administration which had asserted itself in Tindouf, with its system of committees and elected camp assemblies. In 1976, the situation was further complicated by the Sahrawi Republic assuming functions of government in the camps and Polisario-held territories of Western Sahara. The SADR and Polisario institutions often overlapped, and their division of power was often hard to ascertain.

A more comprehensive merger of these different organizational patterns (military organization/refugee camps/SADR) was not achieved until the 1991 congress, when both the Polisario and SADR organizations were overhauled, integrated into the camp structure and further separated from each other. This followed protests calling for expanding the internal democracy of the movement, and also led to important shifts of personnel in the top tiers of both Polisario and SADR.

Present structure

The organizational order described below applies today, and was roughly finalized in the 1991 internal reforms of the movement, although minor changes have been made since then.

The Polisario Front is led by a Secretary General. The first Secretary General was Brahim Gali,[14] replaced in 1974 by El-Ouali at the II Congress of the Polisario Front, followed by Mahfoud Ali Beiba as Interim Secretary General upon his death. In 1976, Mohamed Abdelaziz was elected at the III Congress of the Polisario, and held the post until his death in 2016. The Secretary General is elected by the General Popular Congress (GPC), regularly convened every four years. The GPC is composed of delegates from the Popular Congresses of the refugee camps in Tindouf, which are held biannually in each camp, and of delegates from the women's organization (UNMS), youth organization (UJSARIO), workers' organization (UGTSARIO) and military delegates from the SPLA (see below).

All residents of the camps have a vote in the Popular Congresses, and participate in the administrative work in the camp through base-level 11-person cells, which form the smallest unit of the refugee camp political structure. These typically care for distribution of food, water and schooling in their area, joining in higher-level organs (encompassing several camp quarters) to cooperate and establish distribution chains. There is no formal membership of Polisario; instead, anyone who participates in its work or lives in the refugee camps is considered a member.

Between congresses, the supreme decision-making body is the National Secretariat, headed by the Secretary General. The NS is elected by the GPC. It is subdivided into committees handling defense, diplomatic affairs, etc. The 2003 NS, elected at the 11th GPC in Tifariti, Western Sahara, has 41 members. Twelve of these are secret delegates from the Moroccan-controlled areas of Western Sahara. This is a shift in policy, as the Polisario traditionally confined political appointments to diaspora Sahrawis, for fear of infiltration and difficulties in communicating with Sahrawis in the Moroccan-controlled territories. It is probably intended to strengthen the movement's underground network in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, and link up with the rapidly growing Sahrawi civil rights activism.

In 2004, an anti-ceasefire and anti-Abdelaziz opposition fraction, the Front Polisario Khat al-Shahid announced its existence, in the first break with the principle of "national unity" (i.e., working in one single organization to prevent internal conflict). It calls for reforms in the movement, as well as resumption of hostilities with Morocco. But it remains of little importance to the conflict, as the group had split in two factions, and Polisario has refused dialogs with it, stating that political decisions must be taken within the established political system.

Armed forces (SPLA)

The Sahrawi People's Liberation Army, (SPLA; also romanized as Saharawi; often abbreviated as ELPS or ELP from the Spanish: Ejército de Liberación Popular Saharaui), is the SADR's army and previously served as the armed wing of the Polisario prior to the foundation of the Republic.[15] Its commander-in-chief was the Secretary General of the Polisario, but the army is now also integrated into the SADR government through the SADR Minister of Defence. The SADR and the Polisario Front have no navy or air force. The SPLA's armed units are considered to have a manpower of possibly 6000–7000 active soldiers today, but during the war years its strength appears to have been significantly higher: up to 20,000 men. It has a potential manpower of many times that number, since both male and female refugees in the Tindouf camps undergo military training at age 18. Women formed auxiliary units protecting the camps during war years.

Equipment

When it originally began the anti-Spanish rebellion, Polisario was forced to capture its weapons individually, and transport them only by foot or camel. But the insurgents multiplied their arsenal and military sophistication after striking an alliance with Algeria in 1975. The modern SPLA is equipped mainly with outdated Russian-manufactured weaponry, donated by Algeria. But its arsenals display a bewildering variety of material, much of it captured from Spanish, Mauritanian (Panhard AMLs) or Moroccan forces (Eland Mk7s, Ratel IFVs, AMX-13s, SK-105 Kürassiers) and made in France, the United States, South Africa, Austria, or Britain. The SPLA has several armored units, composed of old tanks (T-55s, T-62s), somewhat more modern armored cars (EE-9 Cascavels, BRDM-2s), infantry fighting vehicles (BMP-1s, BTR-60s), rocket launchers (BM-21s, BM-30s) and halftracks. Surface-to-air missiles (anti-aircraft missiles, as SA-6s, SA-7s, SA-8s and SA-9s) have downed several Moroccan F-5 fighter jets, and helped compensate for the complete Moroccan control of the skies.[16]

One of the most innovative tactics of the SPLA was its early and extensive use of Land Rovers and other re-modeled civilian vehicles, mounting anti-aircraft machine guns (as ZPU-2 or ZU-23) or anti-tank missiles, (as the AT-3 Sagger) and using them in great numbers, to overwhelm unprepared garrisoned outposts in rapid surprise strikes. This may reflect the movement's difficulties in obtaining original military equipment, but nonetheless proved a powerful tactic.[17]

On 3 November 2005, the Polisario Front signed the Geneva Call, committing itself to a total ban on landmines, and later began to destroy its landmine stockpiles under international supervision. Morocco is one of 40 governments that have not signed the 1997 mine ban treaty. Both parties have used mines extensively in the conflict, but some mine-clearing operations have been carried out under MINURSO supervision since the ceasefire agreement.[18][19]

Tactics

The SPLA traditionally employed ghazzi tactics, i.e., motorized surprise raids over great distances, which were inspired by the traditional camel-back war parties of the Sahrawi tribes. However, after the construction of the Moroccan Wall this changed into tactics more resembling conventional warfare, with a focus on artillery, snipers and other long-range attacks. In both phases of the war, SPLA units relied on superior knowledge of the terrain, speed and surprise, and on the ability to retain experienced fighters.

Defections

Since the end of the 1980s, several members of the Polisario have decided to discontinue their military or political activities for the Polisario Front. Most of them returned from the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria to Morocco, among them a few founder members and senior officials. Some of them are now actively promoting Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara, which Morocco considers its Southern Provinces.

Foreign relations

Today 45 countries around the world recognize the legitimacy of the Polisario over Western Sahara. Support for the Polisario Front came mostly from newly independent African states, including Angola and Namibia. Most of the Arab world had supported Morocco; only Algeria and Libya have, at different times, given any significant support to Polisario. Iran recognized the SADR in 1980, Mauritania had recognized the SADR in 1984, and Syria and South Yemen had supported the Polisario position on the conflict when they were all members of the Front of Refusal. Additionally, many third world non-aligned countries have supported the Polisario Front. Ties with Fretilin of East Timor (occupied by Indonesia in 1975) were exceptionally strong and remain so after that country's independence; both Polisario and Fretilin have argued that there are numerous historical parallels between the two conflicts.[20][21][22]

The movement's main political and military backers were originally Algeria and Libya, with Cuba coming a very distant third. Mauritania also attempts to avoid involvement and to balance between Morocco and Polisario's backers in Algeria, although it formally recognizes the SADR as Western Sahara's government since 1984 and has a substantial Sahrawi refugee population (around 30,000) on its territory. Support from Algeria remains strong, despite the country's preoccupation with its own civil war. The Polisario is practically dependent on its bases and refugee camps, located on Algerian soil. While Sahrawis' right to wage an armed struggle against Morocco, and has helped to equip the SPLA, the government also seems to have barred Polisario from returning to armed struggle after 1991, attempting to curry favor from the US and France and to avoid inflaming its already poor relations with Morocco.[23]

Apart from the Algerian military, material and humanitarian aid, food and emergency resources are provided by international organizations such as the WHO and UNHCR. Valuable contributions also come from the strong Spanish solidarity organizations.

Western Sahara in the Cold War

The most intense open warfare in the conflict in Western Sahara occurred during the Cold War. However, the conflict was never fully dragged into the United-States–Soviet dynamics like many other conflicts. This was mainly because both sides tried to avoid overt involvement, which would necessitate a crash in relations with either Morocco or Algeria – the major North African players – and because neither viewed it as an important front. Morocco was firmly entrenched in the US camp, whereas Algeria aligned generally with the Soviet Union during the 1970s, and took a more independent "third-worldist" position after that.

The United States claimed political neutrality on the issue, but militarily backed Morocco against Polisario during the Cold War, especially during the Reagan administration. Despite this, Polisario never received counter-support from the Soviet Union (or the People's Republic of China, the third and junior player in the Cold War). Instead, the entire Eastern Bloc decided in favor of ties and trade with Morocco and refused to recognize the SADR. This made the Polisario almost wholly dependent mainly on Algeria and Libya and some African and Latin American third world countries for political support, plus some NGOs from European countries (Sweden, Norway, Spain, etc.) which generally only approached the issue from a humanitarian angle. The ceasefire coincided with the end of the Cold War. World interest in the conflict seemed to expire in the 1990s as the Sahara question gradually sank from public consciousness due to decreasing media attention.

International recognition of the SADR

A key diplomatic dispute between Morocco and Polisario is over the international diplomatic recognition of the SADR as a sovereign state and Western Sahara's legitimate government. In 2004, South Africa announced formal recognition of the SADR, delayed for ten years despite unequivocal promises by Nelson Mandela as apartheid fell. This came since the announced referendum for Western Sahara was never held. Kenya and Uruguay followed in 2005, and relations were upgraded in some other countries, while recognition of the SADR was cancelled by others (Albania, Chad, Serbia); in 2006, Kenya suspended its decision to recognize the SADR to act as a mediating party.

See also

References

- Member parties of the Socialist International – Observer parties. Socialistinternational.org.

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 34/37: Question of Western Sahara. Adopted on 21 November 1979. Full document, retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Stefan Gänzle; Benjamin Leruth; Jarle Trondal (15 November 2019). Differentiated Integration and Disintegration in a Post-Brexit Era. Taylor & Francis. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-429-64884-7.

- Pro-Sahrawi demo held in Spain PressTV, 14 November 2010.

- "Proyecto Desaparecidos: Mohamed Basiri el mas antiguo desaparecido saharaui".

- Lippert 1992, p. 638.

- Shelley, Toby (2004). Endgame in the Western Sahara: What Future for Africa's Last Colony?. London: Zed Books. pp. 171–172. ISBN 1-84277-340-2.

- Arieff, Alexis (8 October 2014). "Western Sahara" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "Mauritania profile - Timeline". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Brennan, David (15 November 2020). "Fighting in Morocco May Present Biden with Fresh Africa Crisis Amid COVID Surge". msn.com. Newsweek. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- "'11 Sept has not influenced Western Sahara's situation'". Afrol.net.

- "'Africa's last colony'". 21 October 2003 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- "Algeria Claims Spanish Sahara Is Being Invaded". The Monroe News-Star. 1 January 1976. Retrieved 19 October 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tomás Bárbulo, La historia prohibida del Sáhara Español, Destino, 2002, Pages 105–106

- "Editor Chris Brazier’s Journey Into Polosario Territory, Including His Trip Through A Cleared Minefield, A Visit To An Underground Hospital, And To A Guerrilla Army Base". New Internationalist.

- "Moroccan Air Force at 50". Air Scene UK.

- Michael Bhatia, "Western Sahara under Polisario Control: Summary Report of Field Mission to the Sahrawi Refugee Camps (near Tindouf, Algeria)". ARSO.org.

- "genevacall.org". Archived from the original on 1 June 2006.

- "genevacall.org". Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- Ramos-Horta, Jose (31 October 2005). "The dignity of the ballot". The Guardian.

- "Timor achieves UN dream". East Timor Action Network.

- "LATEST DEVELOPMENTS ON WESTERN SAHARA". ARSO.org (26 March 2004).

- MERIP.org. Middle East Research and Information Project. Archived 10 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Lippert, Anne (1992). "Sahrawi Women in the Liberation Struggle of the Sahrawi People". Signs. The University of Chicago Press. 17 (3): 636–651. doi:10.1086/494752. JSTOR 3174626.

Further reading

- Jarat Chopra, United Nations Determination of the Western Saharan Self (Norwegian Institute of Foreign Affairs 1994)

- Tony Hodges, Western Sahara. The Roots of a Desert War (Lawrence & Hill 1983)

- Leo Kamil, Fueling the Fire. U.S. policy & the Western Sahara Conflict (Red Sea Press 1987)

- Anthony G. Pazzanita & Tony Hodges, Historical dictionary of Western Sahara (2nd ed. Scarecrow Press 1994)

- Toby Shelley, Endgame in the Western Sahara (Zed Books 2004)

- Forced Migration Organization: FMO Research Guide Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polisario Front. |