Climate change policy of the United States

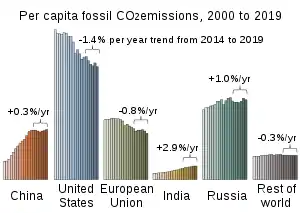

Global climate change was first addressed in United States policy beginning in the early 1950s. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines climate change as "any significant change in the measures of climate lasting for an extended period of time." Essentially, climate change includes major changes in temperature, precipitation, or wind patterns, as well as other effects, that occur over several decades or longer.[2] Climate change policy in the U.S. has transformed rapidly over the past twenty years and is being developed at both the state and federal level.[3]

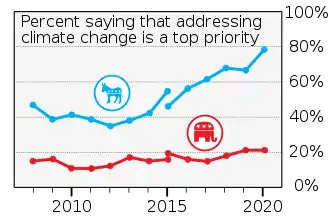

The politics of global warming and climate change have polarized certain political parties and other organizations. The Democratic Party tends to advocate for an expansion of climate change mitigation policies whereas the Republican Party tends to advocate for inaction or a reversal of existing climate change mitigation policies. Most lobbying on climate policy in the United States is done by corporations that are publicly opposed to reducing carbon emissions.[4]

Federal policy

International law

The United States, although a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol, has neither ratified nor withdrawn from the protocol. In 1997, the US Senate voted unanimously under the Byrd–Hagel Resolution that it was not the sense of the Senate that the United States should be a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol. In 2001, former National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, stated that the Protocol "is not acceptable to the Administration or Congress".[5]

The United States has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol.[6] The protocol is non-binding over the United States unless ratified. Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump did not submit the treaty for ratification.

In October 2003, the Pentagon published a report titled An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security by Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall. The authors conclude by stating, "this report suggests that, because of the potentially dire consequences, the risk of abrupt climate change, although uncertain and quite possibly small, should be elevated beyond a scientific debate to a U.S. national security concern."[7]

Congress

In October 2003 and again in June 2005, the McCain-Lieberman Climate Stewardship Act failed a vote in the US Senate.[8] In the 2005 vote, Republicans opposed the Bill 49–6, while Democrats supported it 37–10.[9]

In January 2007, Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced she would form a United States Congress subcommittee to examine global warming.[10] Sen. Joe Lieberman said, "I'm hot to get something done. It's hard not to conclude that the politics of global warming has changed and a new consensus for action is emerging and it is a bipartisan consensus."[11] Senators Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Barbara Boxer (D-CA) introduced the Global Warming Pollution Reduction Act on January 15, 2007. The measure would provide funding for R&D on geologic sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2), set emissions standards for new vehicles and a renewable fuels requirement for gasoline beginning in 2016, establish energy efficiency and renewable portfolio standards beginning in 2008 and low-carbon electric generation standards beginning in 2016 for electric utilities, and require periodic evaluations by the National Academy of Sciences to determine whether emissions targets are adequate.[12] However, the bill died in committee. Two more bills, the Climate Protection Act and the Sustainable Energy Act, proposed February 14, 2013, also failed to pass committee.[13]

The House of Representatives approved the American Clean Energy and Security Act (ACES) on June 26, 2009, by a vote of 219–212, but the bill failed to pass the Senate.[14][15]

In March 2011, the Republicans submitted a bill to the U.S. congress that would prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from regulating greenhouse gasses as pollutants.[16] As of July 2012, the EPA continues to oversee regulation under the Clean Air Act.[17][18]

Clinton administration

Upon the start of his presidency in 1993, Bill Clinton committed the United States to lowering their greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2000 through his biodiversity treaty,[19] reflecting his attempt to return the United States to the global platform of climate policy. Clinton's British Thermal Unit (BTU) Tax and Climate Change Action Plan were also announced within the first year of his presidency, calling for a tax on energy heat content and plans for energy efficiency and joint implementations, respectively.

The Climate Change Action Plan was announced on October 19, 1993. This plan aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2000.[20] Clinton described this goal as "ambitious but achievable," and called for 44 action steps to achieve this goal. Among these steps were voluntary participation by industry, especially those in the commercial and energy supply fields. Clinton allotted $1.9 billion to fund this plan from the federal budget and called for an additional $60 billion funding to come voluntarily businesses and industries.[20]

The British Thermal Tax proposed by Clinton in early 1993 called for a tax on producers of gasoline, oil, and other fuels based on fuel content in accordance to the British Thermal Unit (BTU). The British Thermal Unit is a measure of heat corresponding to the quantity of heat needed to raise the temperature of water by one degree Fahrenheit.[21] The tax also applied to electricity produced by hydro and nuclear power, but exempted renewable energy sources such as geothermal, solar, and wind. The Clinton Administration planned to collect up to $22.3 billion in revenue from the tax by 1997.[22] The tax was opposed by the energy-intensive industry, who feared that the price increase caused by the tax would make U.S. products undesirable on an international level, and thus was never fully implemented.[23]

In 1994, the U.S. called for a new limit on greenhouse gas emissions post-2000 in at the August 1994 INC-10. They also called for a focus on joint implementation, and for new developing countries to limit their emissions. Environmental groups, including the Climate Action Network (CAN), critiqued these efforts, questioning U.S. focus on limiting the emissions of other countries when it had not established its own.[24]

The U.S. government under Clinton succeeded in pushing its agenda for joint implementation in the 1995 Conference of the Parties (COP-1). This victory is noted in the Berlin Mandate of April 1995, which called for developed countries to lead the implementation of national mitigation policies.[25]

Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol on behalf of the United States in 1997, pledging the country to a non-binding 7% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.[26] He claimed that the agreement was "environmentally strong and economically sound," and expressed a desire for greater involvement in the treaty by developing nations.[27]

In his second term, Clinton announced his FY00 proposal, which allotted funding for a new set of environmental policies. Under this proposal, the President announced a new Clean Air Partnership Fund, new tax incentives and investments, and funding for environmental research of both natural and manmade changes to the climate.[28]

The Clean Air Partnership Fund was proposed to finance state and local government efforts for greenhouse gas emission reductions in cooperation with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Under this fund, $200 million was allotted to promote and finance innovation projects meant to reduce air pollution. It also supported the creation of partnerships between the local and federal governments, and private sector.[29]

The Climate Change Technology Initiative provided $4 billion in tax incentives over a five-year period. The tax credits applied to energy efficient homes and building equipment, implementation of solar energy systems, electric and hybrid vehicles, clean energy, and the power industry.[30] The Climate Change Technology Initiative also provided funding for additional research and development on clean technology, especially in the building, electricity, industry, and transportation sectors.[28]

G.W. Bush administration

In March 2001, the George W. Bush Administration announced that it would not implement the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty signed in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan that would require nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, claiming that ratifying the treaty would create economic setbacks in the U.S. and does not put enough pressure to limit emissions from developing nations.[31] In February 2002, President Bush announced his alternative to the Kyoto Protocol, by bringing forth a plan to reduce the intensity of greenhouse gasses by 18 percent over 10 years. The intensity of greenhouse gasses specifically is the ratio of greenhouse gas emissions and economic output, meaning that under this plan, emissions would still continue to grow, but at a slower pace. Bush stated that this plan would prevent the release of 500 million metric tons of greenhouse gases, which is about the equivalent of 70 million cars from the road. This target would achieve this goal by providing tax credits to businesses that use renewable energy sources.[32]

The Bush administration has been accused of implementing an industry-formulated disinformation campaign designed to actively mislead the American public on global warming and to forestall limits on "climate polluters", according to a report in Rolling Stone magazine that reviews hundreds of internal government documents and former government officials.[33] The book Hell and High Water asserts that there has been a disingenuous, concerted and effective campaign to convince Americans that the science is not proven, or that global warming is the result of natural cycles, and that there needs to be more research. The book claims that, to delay action, industry and government spokesmen suggest falsely that "technology breakthroughs" will eventually save us with hydrogen cars and other fixes. It calls on voters to demand immediate government action to curb emissions.[34] Papers presented at an International Scientific Congress on Climate Change, held in 2009 under the sponsorship of the University of Copenhagen in cooperation with nine other universities in the International Alliance of Research Universities (IARU), maintained that the climate change skepticism that is so prevalent in the USA[35] "was largely generated and kept alive by a small number of conservative think tanks, often with direct funding from industries having special interests in delaying or avoiding the regulation of greenhouse gas emissions".[36]

According to testimony taken by the U.S. House of Representatives, the Bush White House pressured American scientists to suppress discussion of global warming[37][38] "High-quality science" was "struggling to get out", as the Bush administration pressured scientists to tailor their writings on global warming to fit the Bush administration's skepticism, in some cases at the behest of an ex-oil industry lobbyist. "Nearly half of all respondents perceived or personally experienced pressure to eliminate the words 'climate change,' 'global warming' or other similar terms from a variety of communications." Similarly, according to the testimony of senior officers of the Government Accountability Project, the White House attempted to bury the report "National Assessment of the Potential Consequences of Climate Variability and Change", produced by U.S. scientists pursuant to U.S. law,[39] Some U.S. scientists resigned their jobs rather than give in to White House pressure to underreport global warming.[37] and removed key portions of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report given to the U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee about the dangers to human health of global warming.[40]

The Bush Administration worked to undermine state efforts to mitigate global warming. Mary Peters, the Transportation Secretary at that time, personally directed US efforts to urge governors and dozens of members of the House of Representatives to block California's first-in-the-nation limits on greenhouse gases from cars and trucks, according to e-mails obtained by Congress.[41]

Obama administration

New Energy for America is a plan to invest in renewable energy, reduce reliance on foreign oil, address the global climate crisis, and make coal a less competitive energy source. It was announced during Barack Obama's presidential campaign.

On November 17, 2008, President-elect Barack Obama proposed, in a talk recorded for YouTube, that the US should enter a cap and trade system to limit global warming.[42]

President Obama established a new office in the White House, the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy, and selected Carol Browner as Assistant to the President for Energy and Climate Change. Browner is a former administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and was a principal of The Albright Group LLC, a firm that provides strategic advice to companies.[43]

The American Clean Energy and Security Act, a cap and trade bill, was passed on June 26, 2009 in the House of Representatives, but was not passed by the Senate.

On January 27, 2009, Secretary of State Clinton appointed Todd Stern as the department's Special Envoy for Climate Change.[44] Clinton said, "With the appointment today of a special envoy we are sending an unequivocal message that the United States will be energetic, focused, strategic and serious about addressing global climate change and the corollary issue of clean energy."[45] Stern, who had coordinated global warming policy in the late 1990s under the Bill Clinton administration, said that "The time for denial, delay and dispute is over.... We can only meet the climate challenge with a response that is genuinely global. We will need to engage in vigorous, dramatic diplomacy."[45]

In February 2009, Stern said that the US would take a lead role in the formulation of a new climate change treaty in Copenhagen in December 2009. He made no indication that the U.S. would ratify the Kyoto Protocol in the meantime.[46] US Embassy dispatches subsequently released by whistleblowing site WikiLeaks showed how the US 'used spying, threats and promises of aid' to gain support for the Copenhagen Accord, under which its emissions pledge is the lowest by any leading nation.[47][48]

President Obama said in September 2009 that if the international community would not act swiftly to deal with climate change that "we risk consigning future generations to an irreversible catastrophe...The security and stability of each nation and all peoples—our prosperity, our health, and our safety—are in jeopardy, and the time we have to reverse this tide is running out." [49]

The president said in 2010 that it was time for the United States "to aggressively accelerate" its transition from oil to alternative sources of energy and vowed to push for quick action on climate change legislation, seeking to harness the deepening anger over the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.[50]

The 2010 United States federal budget proposed to support clean energy development with a 10-year investment of US$15 billion per year, generated from the sale of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions credits. Under the proposed cap-and-trade program, all GHG emissions credits would be auctioned off, generating an estimated $78.7 billion in additional revenue in FY 2012, steadily increasing to $83 billion by FY 2019.[51]

New rules for power plants were proposed March 2012.[52][53]

In US and China's Sunnylands Summit on June 8, 2013, President Obama and Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping worked in accordance for the first time, formulating a landmark agreement to reduce both production and consumption of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). This agreement had the unofficial goal of decreasing roughly 90 gigatons of CO2 by 2050 and implementation was to be led by the institutions created under the Montreal Protocol, while progress was tracked using the reported emissions that were mandated under the Kyoto Protocol. The Obama administration viewed HFCs as a "serious climate mitigation concern." [54]

On March 31, 2015, the Obama administration formally submitted the US Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) for greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). According to the US submission, the United States committed to reducing emissions 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025, a reflection of the Obama administration's goal to convert the U.S. economy into one low-carbon reliance.[55][56]

In 2015, Obama also announced the Clean Power Plan, which is the final version of regulations originally proposed by the EPA the previous year, and which pertains to carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.[57]

In the same year, President Obama announced his aim for a 40-45% reduction below 2012 levels in methane emissions by 2025, recognizing the potency and prevalence of these emissions within the oil and gas industry. In March 2016, the President would later solidify this goal in an agreement with Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, stating that the two federal governments will jointly work together to reduce methane emissions in North America. The nations released a joint statement outlining general methods and strategies to reach such goals within their respective jurisdictions. In adherence to this goal, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) would take on the responsibility in regulating methane emissions, requiring information from big-time methane emitting industries. Emission information from these industries would be used in the promotion of research and development for methane reduction, formulating differentiated standards and cost-effective policies. The United States and Canada will jointly exchange any progress in research and development for optimal efficiency, while practicing transparency in regards to their respective progress with each other and the rest of North America, continuing to strengthen the bond with Mexico.[58]

On May 12, 2016, after three public hearing and a review of over 900,000 public comments, the administration took the next step to reduce methane emissions. The administration released an Information Collection Request (ICR), requiring all methane emitting operations to provide reports of their levels of emissions for EPA analysis so that policies could begin to be formulated and high emitting sources could be identified. New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) were implemented, building off previous requirements to reduce VOC emissions (byproduct of methane). The new standards set emission limits for methane; reductions were to be made through transition to newer and cleaner production equipment, fixed monitoring of leaks at operation sites using innovative techniques, and the capturing of emissions from hydraulic fracturing. More specifically, well sites, regardless of size or operation, were to be checked for leaks at least twice a year, while compressor stations were required to monitor every quarter. Owners and operators can make these observances one of two ways, either through optical gas imaging or through the use of a portable monitoring instrument; innovative strategies to monitor leaks must be approved. Once these checks are made, mandatory surveys must be submitted no later than a year after final results are gathered. Additionally, "green completion" requirements, regarding the process for seizing emissions from hydraulically fractured oil wells, were outlined for owners of oil wells.[59]

A September 2016 study from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory analyses a set of definite and proposed climate change policies for the United States and finds that these are just insufficient to meet the US intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) under the 2015/2016 Paris Agreement. Additional greenhouse gas reduction measures will probably be required to meet this international commitment.[60] These additional reduction measures will soon have to be decided on in order to start complying with the agreement's "below 2 degrees" goal, and countries may have to be more proactive than previously thought[61]

An October 2016 report compares US government spending on climate security and military security and finds the latter to be 28 × greater. The report estimates that public sector spending of $55 billion is needed to tackle climate change. The 2017 national budget contains $21 billion for such expenditures, leaving a shortfall of $34 billion that could be recouped by scrapping underperforming weapons programs. The report nominates the F-35 fighter and close-to-shore combat ship projects as possible targets.[62][63][64]

President's 21st century clean transportation plan

In June 2015, the Obama administration released the President's 21st Century Clean Transportation Plan with the goal of reducing carbon pollution by converting the nation's century old infrastructure into one based on clean energy. This plan intended to battle climate change by reducing emissions through a switch to more sustainable forms of transportation, resulting from a potential increase of innovation in both public transit and electric vehicle production in the United States. The President stated that the revitalization of the infrastructure would not only create jobs, but also allow for quicker deliveries of goods, and allow for a greater variety of transportation options that would facilitate travel for Americans. The President's multibillion-dollar proposal provided incentives to reduce reliance on international oil and fossil fuels.[65]

This plan fundamentally relied on an increase in investment into sustainable transportation, Previously, such investment into transportation was supported by the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST), an act passed in December 2015 by the Obama administration. FAST was formulated to reduce traffic and increase the quality of air by reducing emissions, yet this act proved to be slow in gathering infrastructure investments.[66] Thus, the President proposed a tax on oil, a gradual $10 per barrel, in order to subsidize this plan to improve infrastructure and further drive down the incentive to consume large quantities of oil, possibly furthering the urge to switch to more sustainable forms of transportation. Ultimately, this plan did not appeal to GOP leaders and as a result it was never enacted; the act was denied funding in the House of Representatives by U.S. Congressman Paul A. Gosar and his Republican coalition, enacting their fundamental "power of the purse."[67]

Climate action plan progress report

In June 2015, under Obama's Climate Action Plan Progress Report, the EPA announced that they were going to propose new standards for both medium and heavy-duty engines and vehicles, building off standards that were already enacted. These proposals were projected to decrease emissions by 270 million metric tons and save vehicle owners around $50 billion in fuel costs.[68]

The Climate Action Plan progress report also addressed air craft, transit, and maritime emissions. The EPA released an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, increasing transparency around the plans of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in tightening carbon pollution standards. Additionally, under the Next Generation Transportation System (NextGen), the Federal Aviation Administration has worked jointly with the aviation industry in formulating technology that supports a reduction in emissions and increase in fuel efficiency. With respect to maritime emissions, the Obama administration oversaw, in cooperation with the Maritime Administration, the increase of investments into more fuel-efficient ships, finalizing the creation of two ships that have been used in the Puerto-Rico to Jacksonville route. Similar investments were pumped into transit, which made it possible for buses and other forms of transit to switch to other forms of energy such as natural gas and electric.[68]

Model year 2012-2016 standards and model year 2017-2025 standards

In April 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Transportation's National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) formulated a national program that would finalize new standards for model year 2012 through 2016 passenger cars, light-duty trucks, and medium duty passenger vehicles. With these new standards, vehicles were required to meet an average emissions level of 250 grams of carbon dioxide per mile by model year 2016. This was the first time the EPA had taken measures to regulate vehicular GHG emissions under the Clean Air Act. Additionally, the administration established Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act.[69]

In August 2012, the administration expanded on these standards for model years 2017 through 2025 vehicles, issuing final rules and standards that were to result in a 163 gram emission per mile by model year 2025.[70]

Trump administration

During his campaign, Donald Trump made promises to roll back some of the Obama-era regulations enacted with the purpose of combating climate change. He has questioned if climate change is real and has indicated that he will focus his efforts on other causes as president. Trump has also expressed that efforts to curb fossil fuel industries hurt the United States' global competitiveness.[71] He pledged to roll back regulations placed on the oil and gas industry by the EPA under the Obama administration in order to boost the productivity of both industries.[72]

President Trump appointed Scott Pruitt to head the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). While serving as Attorney General of Oklahoma, Pruitt removed Oklahoma's environmental protection unit and sued the EPA a total of fourteen times, thirteen of which involved "industry players" as co-parties.[73] He was confirmed to head the EPA on February 17, 2017 with a 52–46 vote[74] and resigned on July 5, 2018 amid ethics controversies. He was replaced by Andrew Wheeler, who was formally confirmed on February 28, 2019 by a 52–47 vote.[75]

President Trump appointed Rex W. Tillerson, the former chairman and CEO of Exxon Mobil, as secretary of state. His nomination was confirmed on February 1, 2017 by a 56–43 vote.[76] He was fired on March 31, 2018 and replaced by Mike Pompeo.

An Environmental Impact Statement (EIP) published by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration acknowledges that, without a course correction, the planet is on track for global average temperature warming by approximately four degrees Celsius by the end of the century, compared with preindustrial levels. Such warming would be catastrophic for organized human life, according to scientists. The EIP supports the U.S. government's decision to maintain without increase fuel-efficiency standards for cars and other vehicles.[77]

An executive order was issued by President Trump on January 24, 2017 that removed barriers from the Keystone XL and Dakota Access Pipelines, making it easier for the companies sponsoring them to continue with production.[78] On March 28, 2017, President Trump signed an executive order aimed towards boosting the coal industry. The executive order rolls back on Obama-era climate regulations on the coal industry in order to grow the coal sector and create new American jobs. The White House has indicated that any climate change policies that they deem hinder the growth of American jobs will not be pursued. In addition, the executive order rolls back on six Obama-made orders aimed at reducing climate change and carbon dioxide emissions and calls for a review of the Clean Power Plan.[79]

In his budget proposal for 2018, President Trump proposed cutting the EPA's budget by 31% (reducing its current $8.2 billion to $5.7 billion). Had it passed, it would have been the lowest EPA budget in 40 years even adjusted for inflation,[80] but Congress did not approve it. Trump tried again unsuccessfully in his budget proposal for 2019 to cut EPA funding by 26%.[81][82] The EPA provides technical assistance to cities as they update their infrastructure to adapt to climate change, according to Joel Scheraga, the EPA senior advisor for climate change adaptation who has worked for the EPA for three decades. Scheraga said he was working with a reduced staff under the Trump administration.[83]

Environmental justice

The shift in direction of environmental policy in the United States under the Trump administration has led to a change in the environmental justice sector. On March 9, 2017, Mustafa Ali, a leader of the environmental justice sector in the EPA, resigned over proposed cuts to the environmental justice sector of the EPA. The preliminary budget proposals would cut the environmental justice office's budget by 1/4, causing a 20% reduction in its workforce. The environmental justice program is one of a dozen vulnerable to losing all governmental funding.[84]

The Biden Administration (2021 - present)

The environmental policy of Biden administration is characterized by strong measures for protecting climate and environment.[85]

State and local policy

Across the country, regional organizations, states, and cities are achieving real emissions reductions and gaining valuable policy experience as they take action on climate change. These actions include increasing renewable energy generation, selling agricultural carbon sequestration credits, and encouraging efficient energy use.[86] The U.S. Climate Change Science Program is a joint program of over twenty U.S. cabinet departments and federal agencies, all working together to investigate climate change. In June 2008, a report issued by the program stated that weather would become more extreme, due to climate change.[87][88]

As described in a 2007 brief by the PEW Center on Global Climate Change, "States and municipalities often function as "policy laboratories", developing initiatives that serve as models for federal action. This has been especially true with environmental regulation—most federal environmental laws have been based on state models. In addition, state actions can have a significant impact on emissions, because many individual states emit high levels of greenhouse gases. Texas, for example, emits more than France, while California's emissions exceed those of Brazil."[89]

City and state governments often act as liaisons to the business sector, working with stakeholders to meet standards and increase alignment with city and state goals.[90] This section will provide an overview of major statewide climate change policies as well as regional initiatives.

Arizona

On September 8, 2006, Arizona Governor Janet Napolitano signed an executive order calling on the state to create initiatives to cut greenhouse gas emissions to the 2000 level by the year 2020 and to 50 percent below the 2000 level by 2040.[91]

California

California (the world's sixth largest economy) has long been seen as the state-level pioneer in environmental issues related to global warming and has shown some leadership in the last four years. On July 22, 2002, Governor Gray Davis approved AB 1493, a bill directing the California Air Resources Board to develop standards to achieve the maximum feasible and cost-effective reduction of greenhouse gases from motor vehicles. Now the California Vehicle Global Warming law, it requires automakers to reduce emissions by 30% by 2016. Although it has been challenged in the courts by the automakers, support for the law is growing as other states have adopted similar legislation. On September 7, 2002 Governor Davis approved a bill requiring the California Climate Action Registry to adopt procedures and protocols for project reporting and carbon sequestration in forests. (SB 812. Approved by Governor Davis on September 7, 2002) California has convened an interagency task force, housed at the California Energy Commission, to develop these procedures and protocols. Staff are currently seeking input on a host of technical questions.

In June 2005, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed an executive order[92] calling for the following reductions in state greenhouse gas emissions: 11 percent by 2010, 25 percent by 2020 and 80 percent by 2050. Measures to meet these targets include tighter automotive emissions standards, and requirements for renewable energy as a proportion of electricity production. The Union of Concerned Scientists has calculated that by 2020, drivers would save $26 billion per year if California's automotive standards were implemented nationally.[93]

On August 30, 2006, Schwarzenegger and the California Legislature reached an agreement on AB32, the Global Warming Solutions Act. The bill was signed into law on September 27, 2006, by Arnold Schwarzenegger, who declared, "We simply must do everything we can in our power to slow down global warming before it is too late... The science is clear. The global warming debate is over." The Act caps California's greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by 2020, and institutes a mandatory emissions reporting system to monitor compliance. This agreement represents the first enforceable statewide program in the U.S. to cap all GHG emissions from major industries that includes penalties for non-compliance. This requires the State Air Resources Board to establish a program for statewide greenhouse gas emissions reporting and to monitor and enforce compliance with this program. The legislation will also allow for market mechanisms to provide incentives to businesses to reduce emissions while safeguarding local communities,[94] and authorizes the state board to adopt market-based compliance mechanisms including cap-and-trade, and allows a one-year extension of the targets under extraordinary circumstances.[95] Thus far, flexible mechanisms in the form of project based offsets have been suggested for five main project types. A carbon project would create offsets by showing that it has reduced carbon dioxide and equivalent gases. The project types include: manure management, forestry, building energy, SF6, and landfill gas capture.

Additionally, on September 26 Governor Schwarzenegger signed SB 107, which requires California's three major biggest utilities – Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric – to produce at least 20% of their electricity using renewable sources by 2010. This shortens the time span originally enacted by Gov. Davis in September 2002 to increase utility renewable energy sales 1% annually to 20% by 2017.

Gov. Schwarzenegger also announced he would seek to work with Prime Minister Tony Blair of Great Britain, and various other international efforts to address global warming, independently of the federal government.[96]

Connecticut

The state of Connecticut passed a number of bills on global warming in the early to mid 1990s, including—in 1990—the first state global warming law to require specific actions for reducing CO2. Connecticut is one of the states that agreed, under the auspices of the New England Governors and Eastern Canadian Premiers (NEG/ECP), to a voluntary short-term goal of reducing regional greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2010 and by 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2020. The NEG/ECP long-term goal is to reduce emissions to a level that eliminates any dangerous threats to the climate—a goal scientists suggest will require reductions 75 to 85 percent below current levels.[97] These goals were announced in August 2001. The state has also acted to require additions in renewable electric generation by 2009.[98]

Maryland

Maryland began a partnership with the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) in 2015 to research impacts and solutions to climate change called the Maryland Climate Change Commission.[99]

New York

In August 2009, Governor David Paterson created the New York State Climate Action Council (NYSCAC) and tasked them with creating a direct action plan. In 2010, the NYSCAC released a 428-page Interim Report which outlined a plan to reduce emissions and highlighted the impact climate change will have in the future.[100] In 2010, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority also commissioned a report about statewide climate change impacts, later published in November 2011. After Hurricanes Sandy and Irene along with Tropical Storm Lee, the state updated vulnerability in regards to the condition of its critical infrastructure.

According to the 2015 New York State Energy Plan, renewable sources, which include wind, hydropower, solar, geothermal, and sustainable biomass, have the potential to meet 40 percent of the state's energy needs by 2030. As of 2018, sustainable energy use comprises 11 percent of all energy usage.[101] The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority offers incentives in the form of grants and loans to its residents to adopt renewable energy technologies and create renewable energy businesses.

Other state climate change mitigation laws have gone into effect. The net metering laws make it easier for both residents and businesses to use solar power by feeding unused energy back into electrical fields and receive credit from their power suppliers. Although one version was released in 1997, it was exclusively limited to residential systems using up to 10 kilowatts of power. However, on June 1, 2011, the laws were expanded to include farm and non-residential buildings.[102] The Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard set a statewide target for renewable energy and offered incentives to residents to use the new technologies.[101]

In June 2018, the state announced its first major update in over two decades to its Environmental Quality Review (EQR) regulations. The update involves streamlining the environmental review process and encouraging renewable energy. It also expanded the Type II actions, or "list of actions not subject to further review", including green infrastructure upgrades and retrofits. Furthermore, solar arrays are set to be installed in sites like brownfields, wastewater treatment facilities, and land zoned for industry. The regulations will take effect on January 1, 2019.[100]

New York State Energy Plan

In 2014, Governor Andrew Cuomo enforced the state's hallmark energy policy, Reforming the Energy Vision. This involves building a new network that will connect the central grid with clean, locally generated power. The method for this undertaking falls to the Energy Plan, a comprehensive plan to build a clean, resilient, affordable energy system for all New Yorkers. It will foster "economic prosperity and environmental stewardship" and cooperation between government and industry. Concrete goals thus far include a 40 percent reduction in greenhouse gas from 1990 levels, electricity sourced from 50 percent of renewable energy sources, and a 600 billion Btu increase in statewide energy efficiency.[103]

Regional initiatives

Clean Energy Standards

Clean Energy Standard (CES) policies are policies which favor lowering non-renewable energy emissions and increasing renewable energy use. They are helping to drive the transition to cleaner energy, by building upon existing energy portfolio standards, and could be applied broadly at the federal level and developed more acutely at the regional and state levels. CES policies have had success at the federal level, gaining bipartisan support during the Obama administration. Iowa was the first state to adopt CES policies, and now a majority of states have adopted CES policies.[104] Similar to CES policies, Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) are standards set in place to ensure a greater integration of renewable energies in state and regional energy portfolios. Both CES and RPS are helping increase the use of clean and renewable energies in the United States.

Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

In 2003, New York State proposed and attained commitments from nine Northeast states to form a cap and trade carbon dioxide emissions program for power generators, called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). This program launched on January 1, 2009 with the aim to reduce the carbon "budget" of each state's electricity generation sector to 10 percent below their 2009 allowances by 2018.[105] Ten Northeastern US states are involved in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative,[106] It is believed that the state-level program will apply pressure on the federal government to support Kyoto Protocol. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a cap and trade system for CO2 emissions from power plants in the member states. Emission permit auctioning began in September 2008, and the first three-year compliance period began on January 1, 2009.[107] Proceeds will be used to promote energy conservation and renewable energy.[108] The system affects fossil fuel power plants with 25 MW or greater generating capacity ("compliance entities").[107] Since 2005, the participating states have collectively seen an over 45% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by RGGI-affected power plants. This has resulted in cleaner air, better health, and economic growth.[109]

- Participating states: Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, Rhode Island

- Observer states and regions: Pennsylvania, District of Columbia, Quebec, New Brunswick, Ontario.[110]

Western Climate Initiative

Since February 2007, seven U.S. states and four Canadian provinces have joined together to create the Western Climate Initiative, a regional greenhouse gas emissions trading system.[111] The Initiative was created when the West Coast Global Warming Initiative (California, Oregon, and Washington) and the Southwest Climate Change Initiative (Arizona and New Mexico) joined efforts with Utah and Montana, along with British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec.[112]

The nonprofit organization WCI, Inc., was established in 2011 and supports implementation of state and regional greenhouse gas trading programs.[113]

Powering the Plains Initiative

The Powering the Plains Initiative (PPI) began in 2002 and aims to expand alternative energy technologies and improve climate-friendly agricultural practices.[114] Its most significant accomplishment was a 50-year energy transition roadmap for the upper Midwest, released in June 2007.[115]

- Participating states: Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota, South Dakota, Canadian Province of Manitoba

Litigation by states

Several lawsuits have been filed over global warming. In 2007 the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency that the Clean Air Act gives the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to regulate greenhouse gases, such as tailpipe emissions. A similar approach was taken by California Attorney General Bill Lockyer who filed a lawsuit California v. General Motors Corp. to force car manufacturers to reduce vehicles' emissions of carbon dioxide. A third case, Comer v. Murphy Oil, was filed by Gerald Maples, a trial attorney in Mississippi, in an effort to force fossil fuel and chemical companies to pay for damages caused by global warming.[116]

In June 2011, the United States Supreme Court overturned 8–0 a U.S. appeals court ruling against five big power utility companies, brought by U.S. states, New York City, and land trusts, attempting to force cuts in United States greenhouse gas emissions regarding global warming. The decision gives deference to reasonable interpretations of the United States Clean Air Act by the Environmental Protection Agency.[117][118][119]

Position of political parties and other political organizations

(Discontinuity resulted from survey changing in 2015 from reciting "global warming" to "climate change".)

In the 2016 presidential campaigns, the two major parties established different positions on the issue of global warming and climate change policy. The Democratic Party seeks to develop policies which curb negative effects from climate change.[121] The Republican Party, whose leading members have frequently denied the existence of global warming,[122] continues to meet its party goals of expanding the energy industries [123] and curbing the efforts of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[124] Other parties, including the Green Party, the Libertarian Party, and the Constitution Party possess various views of climate change and mostly maintain their parties' own long-standing positions to influence their party members.

Democratic Party

In its 2016 platform, the Democratic Party views climate change as "an urgent threat and a defining challenge of our time." Democrats are dedicated to "curbing the effects of climate change, protecting America's natural resources, and ensuring the quality of our air, water, and land for current and future generations."[121]

With respect to the climate change, the Democratic Party believes that "carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gasses should be priced to reflect their negative externalities, and to accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy and help meet our climate goals."[125] Democrats are also committed to "implementing, and extending smart pollution and efficiency standards, including the Clean Power Plan, fuel economy standards for automobiles and heavy-duty vehicles, building codes and appliance standards."[125]

Democrats emphasize the importance of environmental justice. The party calls attention to the environmental racism as the climate change has disproportionately impacted low-income and minority communities, tribal nations and Alaska Native villages. The party believes "clean air and clean water are basic rights of all Americans."[125]

Republican Party

The Republican Party has varied views on climate change. The most recent 2016 Republican Platform denies the existence of climate change and dismisses scientists’ efforts of easing global warming.

In 2014, President Barack Obama proposed a series of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations, known as the Clean Power Plan that would reduce carbon pollution from coal-fired power plants. The Republican Party has viewed these efforts as a "war on coal" and has significantly opposed them. Instead, it advocates building the Keystone XL pipeline, outlawing a carbon tax, and stopping all fracking regulations.

Donald Trump, the 45th President of the United States, has said that "climate change is a hoax invented by and for Chinese."[126] During his political campaign, he blamed China for doing little helping the environment on the earth, but he seemed to ignore many projects organized by China to slow global warming. While Trump's words might be counted as his campaign strategy to attract voters, it brought concerns from the left about environmental justice.

From 2008 to 2017, the Republican Party went from "debating how to combat human-caused climate change to arguing that it does not exist," according to The New York Times.[127] In 2011 "more than half of the Republicans in the House and three-quarters of Republican senators" said "that the threat of global warming, as a man-made and highly threatening phenomenon, is at best an exaggeration and at worst an utter 'hoax'", according to Judith Warner writing The New York Times Magazine.[128] In 2014, more than 55% of congressional Republicans were climate change deniers, according to NBC News.[129][130] According to PolitiFact in May 2014, "...relatively few Republican members of Congress...accept the prevailing scientific conclusion that global warming is both real and man-made...eight out of 278, or about 3 percent."[122][131] A 2017 study by the Center for American Progress Action Fund of climate change denial in the United States Congress found 180 members who deny the science behind climate change; all were Republicans.[132][133]

In 2019, some Republican legislators broke with the party to advocate taking action on climate change, with market-based solutions rather than government regulations,[134] and groups of younger Republicans began lobbying efforts in favor of a climate policy response.[135]

The GOP does champion some energy initiatives following: opening up public lands and the ocean for further oil exploration; fast tracking permits for oil and gas wells; and hydraulic fracturing. It also supports dropping "restrictions to allow responsible development of nuclear energy."[121]

Green Party

The Green Party of the United States advocates for reductions of greenhouse gas emissions and increased government regulation.

In 2010 Platform on Climate Change, the Green Party leaders released their proposal to solve and integrate the problem and policy of climate change with six parts. First, Greens (the members of the Green Party) want a stronger international climate treaty to decrease greenhouse gases at least 40% by 2020 and 95% by 2050. Second, Greens advocate economic policies to create a safer atmosphere. The economic policies include setting carbon taxes on fossil fuels, removing subsidies for fossil fuels, nuclear power, biomass and waste incineration, and biofuels, and preventing corrupt actions from the rise of carbon prices. Third, countries with few contributions should pay for adaption to climate change. Fourth, Greens champion more efficient but low-cost public transportation system and less energy demand economy. Fifth, the government should train more workers to operate and develop the new, green energy economy. Last, Greens think necessary to transform commercial plants where have uncontrolled animal feeding operations and overuse of fossil fuel to health farms with organic practices.[136]

Libertarian Party

In its 2016 platform, the Libertarian Party states that "competitive free markets and property rights stimulate the technological innovations and behavioral changes required to protect our environment and ecosystems."[137] The Libertarians believe the government has no rights or responsibilities to regulate and control the environmental issues. The environment and natural resources belong to the individuals and private corporations.

Constitution Party

The Constitution Party, in the 2014 Platform, states that "it is our responsibility to be prudent, productive, and efficient stewards of God's natural resources."[138] On the issue of global warming, it says that "globalists are using the global warming threat to gain more control via worldwide sustainable development."[139] According to the party, eminent domain is unlawful because "under no circumstances may the federal government take private property, by means of rules and regulations which preclude or substantially reduce the productive use of the property, even with just compensation."[138]

In regards to energy, the party calls attention to "the continuing need of the United States for a sufficient supply of energy for national security and for the immediate adoption of a policy of free market solutions to achieve energy independence for the United States," and calls for the "repeal of federal environmental protections."[140] The party also advocates the abolition of the Department of Energy.

Nebraska Farmers Union

In September 2019, the Nebraska Farmers Union called for "more government action on climate change." The organization wants better agricultural research that develops tools for increasing carbon sequestration in soils, and increased participation by government at state and national levels.[141]

Climate and environmental justice

The Environmental Protection Agency defines Environmental justice as: "The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies." [142]

Many studies have shown that those people who are least responsible for causing the problem of climate change are also the most likely to suffer from its impacts. Poor and disempowered groups often do not have the resources to prepare for, cope with or recover from early climate disasters such as droughts, floods, heat waves, hurricanes, etc.[143] This occurs not only within the United States but also between rich nations, who predominantly create the problem of climate change by dumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, and poor nations who have to deal more heavily with the consequences.[143]

With the rapid acceleration of climate change in recent years, many grassroots movements have emerged to combat its impact. Spokespeople within these groups argue that universal access to a clean and healthy environment and access to critical natural resources are basic human rights.[144]

Assessing the impact of climate justice movements on domestic and international government policies can be difficult as these movements tend to operate and participate outside the political arena. Global policy-making has not yet recognized the overarching principles (climate equity, inclusive participation, and human rights) of the movement. Instead, most of those key principles are beginning to emerge in the activity on non-governmental organizations.[145]

State and regional policies

States and local governments are often tasked with defense against climate change affecting areas and peoples under state and local jurisdiction.

Mayors National Climate Action Agenda

The Mayors National Climate Action Agenda was founded by Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti, former Houston mayor Annise Parker, and former Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter in 2014.[146] The MNCAA aims to bring climate change policy into the hands of local government and to make federal climate change policies more accountable.[147][148]

As a part of MNCAA, 75 mayors from across the United States, known as the "Climate Mayors", wrote to President Trump on March 28, 2017 in opposition to proposed rollbacks of several major climate change departments and initiatives. They maintain that the federal government should continue to build up climate change policies, stating "we are also standing up for our constituents and all Americans harmed by climate change, including those most vulnerable among us: coastal residents confronting erosion and sea level rise; young and old alike suffering from worsening air pollution and at risk during heatwaves; mountain residents engulfed by wildfires; farmers struggling at harvest time due to drought; and communities across our nation challenged by extreme weather."[149][150] Climate Mayors currently has over 400 cities involved in the network.[151] Their current key initiative is the Electric Vehicle Request for Information (EV RFI).[152] They have also produced responses to the announcement of the plan for the United States to withdraw from the Paris Agreement[153] and opposition to the proposed repeal of the Clean Power Plan.[154]

United States Climate Alliance

The United States Climate Alliance is a group of states committed to meeting the Paris Agreement emissions targets despite President Trump's announced withdrawal from the agreement. Currently, there are 22 states that are members of this network.[155] This network is a bipartisan network of governors across the United States and is governed by three core principles: "States are continuing to lead on climate change", "State-level climate action is benefiting our economies and strengthening our communities", "States are showing the nation and the world that ambitious climate action is achievable."[156] Their current initiatives include green banks, grid modernizations, solar soft costs, short-lived climate pollutants, natural and working lands, climate resilience, international cooperation, clean transportation, and improving data and tools.[157]

California

The California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (commonly known as AB 32) mandates a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by the year 2020.[158] The Environmental Defense Fund and the Air Resources Board recruited staffers with environmental justice expertise as well as community leaders in order to appease environmental justice groups and ensure the safe passage of the bill.[159]

The environmental justice groups who worked on AB 32 strongly opposed cap and trade programs being made mandatory.[159] A cap and trade plan was put in place, and a 2016 study by a group of California academics found that carbon offsets under the plan were not used to benefit people in California who lived near power plants, who are mostly less well off than people who live far from them.[160]

See also

- Carbon pricing

- Citizens' Climate Lobby

- Climate change in the United States

- Greenhouse gas emissions by the United States

- List of climate change initiatives#North America

- Midwestern Greenhouse Gas Accord

- Politics of the United States

- Public opinion on climate change

- Regulation of greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act

- Scientific consensus on climate change

- The Climate Registry

- The Republican War on Science – a 2005 book by Chris Mooney

- U.S. Climate Change Science Program

- United States Wind Energy Policy

- Western Climate Initiative

References

- Friedlingstein et al. 2019, Table 7.

- EPA, OAR, OAP, CCD, US. "Climate Change: Basic Information". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-12.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Federal Action on Climate". Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. 2017-10-21. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- Cory, Jared; Lerner, Michael; Osgood, Iain (2020). "Supply Chain Linkages and the Extended Carbon Coalition". American Journal of Political Science. doi:10.1111/ajps.12525. ISSN 1540-5907.

- Kluger, Jeffrey (April 1, 2001). "A Climate of Despair". Time. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- "United Nations Treaty Collection". treaties.un.org. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall (October 2003). "An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- http://www.nwf.org/globalwarming/senateVoteJune05.cfm Archived 2008-09-07 at the Wayback Machine, National Wildlife Federation

- "Summary of The Lieberman-McCain Climate Stewardship Act of 2003 - Center for Climate and Energy Solutions". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- Pelosi creates global warming committee, Associated Press, 1/18/07.

- "Senators sound alarm on climate", The Washington Times, January 31, 2007

- "Climate Change Bills of the 110th Congress". Environmental Defense Fund. May 29, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- "Sanders, Boxer Propose Climate Change Bills". Sen. Bernie Sanders. Retrieved 2015-10-10.

- Broder, John (June 26, 2009). "House Passes Bill to Address Threat of Climate Change". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- Greg G. Hitt; Stephan Power, "House Passes Climate Bill", June 27, 2009; The Wall Street Journal

- Timothy Gardner, "Republicans launch bill to axe EPA carbon rules", Reuters March 3, 2011

- Court Backs E.P.A. Over Emissions Limits Intended to Reduce Global Warming June 26, 2012

- ""This is how science works" on global warming, court rules - Doubtful News". Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- Berke, Richard L. "CLINTON DECLARES NEW U.S. POLICIES FOR ENVIRONMENT". Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- Deangelis, T. (1994). "Clinton's climate change action plan". Environmental Health Perspectives. 102 (5): 448–449. doi:10.1289/ehp.94102448. PMC 1567135. PMID 8593846.

- "British Thermal Units (Btu) - Energy Explained, Your Guide To Understanding Energy - Energy Information Administration". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Greenhouse, Steven. "CLINTON'S ECONOMIC PLAN: The Energy Plan; Fuels Tax: Spreading The Burden". Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Rosenbaum, David E. "CLINTON BACKS OFF PLAN FOR NEW TAX ON HEAT IN FUELS". Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-20. Retrieved 2019-07-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/cop1/07a01.pdf

- "Kyoto Protocol - Targets for the first commitment period | UNFCCC". unfccc.int. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- "AllPolitics - Clinton Hails Global Warming Pact - Dec. 11, 1997". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- "PRESIDENT CLINTON'S CLIMATE CHANGE INITIATIVES". clintonwhitehouse2.archives.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- "02/01/99: PRESIDENT CLINTON'S FISCAL YEAR 2000 EPA BUDGET". archive.epa.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- "Climate Change Technology Initiative". clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Alex Kirby, US blow to Kyoto hopes, 2001-03-28, BBC News.

- Bush unveils voluntary plan to reduce global warming, CNN.com, 2002-02-14.

- Dickinson, Tim (June 8, 2007). "The Secret Campaign of President Bush's Administration To Deny Global Warming". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- Hamilton, Tyler (January 1, 2007). "Fresh alarm over global warming". The Toronto Star. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- Riley Dunlap, "Why climate-change skepticism is so prevalent in the USA: the success of conservative think tanks in promoting skepticism via the media", Climate Change: Global Risks, Challenges and Decisions, Institute of Physics (IOP) Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 6 (2009) 532010 doi:10.1088/1755-1307/6/3/532010

- William Freudenburg, "The effects of journalistic imbalance on scientific imbalance: special interests, scientific consensus and global climate disruption", Climate Change: Global Risks, Challenges and Decisions, IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 6 (2009) 532011 doi:10.1088/1755-1307/6/3/532011

- Zabarenko, Deborah (30 January 2007). "Scientists charge White House pressure on warming". Washington Post. Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Written testimony of Dr. Grifo before the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform of the U.S. House of Representatives on January 30, 2007, archived at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- written testimony of Rick Piltz before the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform of the U.S. House of Representatives on January 30, 2007, archived at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-31. Retrieved 2007-01-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) last visited Jan 30, 07

- Hebert, H. Josef (23 October 2007). "White House edits CDC climate testimony". USA Today. usatoday.com: Gannett. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "How the White House Worked to Scuttle California's Climate Law", San Francisco Chronicle, September 25, 2007 http://www.commondreams.org/archive/2007/09/25/4099/

- "YouTube – A New Chapter on Climate Change". It.youtube.com. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "We're sorry, that page can't be found". Archived from the original on 2016-11-11. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- Whitesides, John (January 26, 2009). "Clinton climate change envoy vows 'dramatic diplomacy'". Reuters. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- Rosenthal, Elisabeth (February 28, 2009). "Obama's Backing Raises Hopes for Climate Pact". The New York Times.

- Carrington, Damian (December 3, 2010). "WikiLeaks cables reveal how US manipulated climate accord". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- "Who's on Board with the Copenhagen Accord". Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- Phelps, Jordyn. "President Obama Says Global Warming is Putting Our Safety in Jeopardy". ABC News. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- Cooper, Helene (June 2, 2010). "Obama Says He'll Push for Clean Energy Bill". The New York Times.

- "President's Budget Draws Clean Energy Funds from Climate Measure". Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- Barringer, Felicity; Gillis, Justin (March 27, 2012). "New Limit Pending on Greenhouse Gas Emissions". The New York Times.

- "New Rules for New Power Plants". The New York Times. March 28, 2012.

- "United States and China Agree to Work Together on Phase Down of HFCs". whitehouse.gov. 2013-06-08. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- "FACT SHEET: U.S. Reports its 2025 Emissions Target to the UNFCCC". whitehouse.gov. 2015-03-31. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/United%20States%20of%20America/1/U.S.%20Cover%20Note%20INDC%20and%20Accompanying%20Information.pdf

- Malloy, Allie (2 August 2015). "Obama unveils major climate change proposal". CNN. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "U.S.-Canada Joint Statement on Climate, Energy, and Arctic Leadership". whitehouse.gov. 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/nsps-overview-fs.pdf

- Greenblatt, Jeffery B; Wei, Max (26 September 2016). "Assessment of the climate commitments and additional mitigation policies of the United States". Nature Climate Change. 6 (12): 1090–1093. doi:10.1038/nclimate3125. ISSN 1758-6798.

- Kanitkar, Tejal; Jayaraman, T (2016). "The Paris Agreement: Deepening the Climate Crisis". Economic & Political Weekly. 51: 4.

- Pennington, Kenneth (8 October 2016). "We have money to fight climate change. It's just that we're spending it on defense". The Guardian. London, UK. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- Pemberton, Miriam; Doctor, Nathan; Powell, Ellen (5 October 2016). "Report: Combat Vs. Climate". Institute for Policy Studies (IPS). Washington DC, USA. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- Pemberton, Miriam; Doctor, Nathan; Powell, Ellen (5 October 2016). Report: Combat Vs. Climate: The Military and Climate Security Budgets Compared (PDF). Washington DC, USA: Institute for Policy Studies (IPS). Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- "FACT SHEET: President Obama's 21st Century Clean Transportation System". whitehouse.gov. 2016-02-04. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- Puentes, Joseph Kane and Robert (8 February 2016). "Don't dismiss Obama's clean transportation plan". Brookings. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- "House Passes Five Gosar Amendments that Defund Obama's Climate Agenda, Protect Vital Water and Energy Resources". About Me | Congressman Paul Gosar. 2016-05-26. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/cap_progress_report_final_w_cover.pdf

- https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P100AKHW.PDF?Dockey=P100AKHW.PDF

- https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P100EZ7C.PDF?Dockey=P100EZ7C.PDF

- "Trump says 'nobody really knows' if climate change is real". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- "U.S. will change course on climate policy, Trump official says". Reuters. 2017-01-30. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- "Trump's EPA Pick Imperils Science—And Earth". Time. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- "Scott Pruitt Confirmed To Lead Environmental Protection Agency". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- King, Ledyard (28 February 2019). "Andrew Wheeler, who's been leading Trump deregulatory charge, confirmed by Senate as EPA chief". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- Harris, Gardiner (2017-02-01). "Rex Tillerson Is Confirmed as Secretary of State Amid Record Opposition". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- Washington Post, 28 Sept. 2018, "Trump Administration Sees a 7-Degree Rise in Global Temperatures by 2100"

- "Trump clears way for controversial oil pipelines". Reuters. 2017-01-25. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- Merica, Dan. "Trump dramatically changes US approach to climate change". CNN. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- Thrush, Glenn; Davenport, Coral (2017-03-15). "Donald Trump Budget Slashes Funds for E.P.A. and State Department". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- King, Ledyard (13 February 2018). "EPA budget would be slashed by a fourth in President Trump's budget and Democrats are upset". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "EPA's Budget and Spending". US EPA. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- Grace, Stephanie. "Weather Warrior". Brown Alumni Magazine. September/October 2018: 50.

- "EPA environmental justice leader resigns, amid White House plans to dismantle program". Washington Post. March 9, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- Rosane, Olivia (28 January 2021). "Biden Signs Sweeping Executive Orders on Climate and Science". Ecowatch. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Engel, Kirsten and Barak Orbach (2008). "Micro-Motives for State and Local Climate Change Initiatives". Harvard Law & Policy Review. 2: 119–137. SSRN 1014749.

- Schmid, Randolph E. (June 19, 2008). "Extreme weather to increase with climate change". Associated Press via Yahoo! News.

- "U.S. experts: Forecast is more extreme weather". NBC News. June 19, 2008.

- "Learning from State Action on Climate Change" (PDF). ClimateKnowledge.org. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- McGarvey, Todd; Morsch, Amy (September 2016). "Local Climate Action: Cities Tackle Emissions of Commercial Buildings" (PDF). Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=politicsNews&storyID=2006-09-11T184027Z_01_N11341321_RTRUKOC_0_US-ENVIRONMENT-EMISSIONS-ARIZONA.xml&WTmodLoc=NewsHome-C3-politicsNews-3 Archived 2007-09-06 at the Wayback Machine Reuters

- http://www.governor.ca.gov/state/govsite/gov_htmldisplay.jsp?BV_SessionID=@@@@0438416297.1118767980@@@@&BV_EngineID=cccdaddelkfifflcfngcfkmdffidfnf.0&sCatTitle=&sFilePath=/govsite/spotlight/060105_update.html

- http://www.climatechoices.org/CA_Policies_Fact_Sheet.pdf Archived February 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Global Warming Bill Clears California Assembly" (Press release). Environmental Defense Fund. August 31, 2006. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- http://gov.ca.gov/index.php?/press-release/4111/ Archived 2006-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- "Blair, Schwarzenegger announce global warming research pact". Associated Press. July 31, 2006.

- "Executive Summary of Connecticut Climate Change Action Plan". Archived from the original on December 10, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- "Executive Summary CCCAP 2005" (PDF). Accessed 2011-05-03. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2009.

- "U.S. Cities and States | Center for Climate and Energy Solutions". www.c2es.org. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- "Overview of New York's Climate Change Preparations - Georgetown Climate Center". georgetownclimatecenter.org. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- "Department of Environmental Conservation". New York State Government. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- "Net Metering/Remote Net Metering and Interconnection - NYSERDA". www.nyserda.ny.gov. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- "New York State Energy Plan". energyplan.ny.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- "Clean Energy Standards: State and Federal Policy Options and Implications | Center for Climate and Energy Solutions". www.c2es.org. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- Memorandum of Understanding Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine – Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

- "Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) CO2 Budget Trading Program - Home". Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- "Overview of RGGI CO2 Budget Trading Program" (PDF). Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, Inc. Oct 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-01. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- "RGGI States Announce Preliminary Release of Auction Application Materials" (PDF). Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, Inc. July 11, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- "The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) - NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation". dec.ny.gov. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) – Participating States Archived 2008-08-20 at the Wayback Machine, Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, Inc.

- WCI Design Documents

- "History". www.westernclimateinitiative.org. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- "Multi-State Climate Initiatives | Center for Climate and Energy Solutions". www.c2es.org. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Commission, California Energy. "Climate Change Portal - Home Page". climatechange.ca.gov. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Carlarne, Cinnamon Piñon (2010-01-01). Climate Change Law and Policy: EU and US Approaches. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199553419.

- Pidot, Justin R. (2006). "Global Warming in the Courts – An Overview of Current Litigation and Common Legal Issues" (PDF). Georgetown University Law Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- "Supreme Court rejects Global Warming lawsuit". Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- "Supreme Court backs EPA over state govts on climate change". CBS News.

- "Supreme court rejects global warming lawsuit". Reuters. June 20, 2011.

- "As Economic Concerns Recede, Environmental Protection Rises on the Public's Policy Agenda / Partisan gap on dealing with climate change gets even wider". PewResearch.org. Pew Research Center. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021.

- "How Do Republicans and Democrats Differ on Climate & Environment Policies? - Planet Experts". Planet Experts. August 5, 2016. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- McCarthy, Tom (November 17, 2014). "Meet the Republicans in Congress who don't believe climate change is real". The Guardian. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

It’s much easier to list Republicans in Congress who think climate change is real than it is to list Republicans who don’t, because there are so few members of the former group. Earlier this year, Politifact went looking for congressional Republicans who had not expressed scepticism about climate change and came up with a list of eight (out of 278).

- Smith, Lindsey J. (September 2, 2016). "Even the basics of climate change are still being debated in the 2016 election: Republican and Democratic platforms lay out very different plans for the environment". The Verge. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- Dudley, Susan E. (Aug 2, 2016). "Republican Platform: Free The EPA". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-09-06.

- "Democrats.org". Democrats.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-20. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- Wong, Edward (November 18, 2016). "Trump Has Called Climate Change a Chinese Hoax. Beijing Says It Is Anything But". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- Davenport, Coral; Lipton, Eric (June 3, 2017). "How G.O.P. Leaders Came to View Climate Change as Fake Science". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

The Republican Party’s fast journey from debating how to combat human-caused climate change to arguing that it does not exist is a story of big political money, Democratic hubris in the Obama years and a partisan chasm that grew over nine years like a crack in the Antarctic shelf, favoring extreme positions and uncompromising rhetoric over cooperation and conciliation.

- Warner, Judith (February 27, 2011). "Fact-Free Science". The New York Times Magazine. pp. 11–12. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

It would be easier to believe in this great moment of scientific reawakening, of course, if more than half of the Republicans in the House and three-quarters of Republican senators did not now say that the threat of global warming, as a man-made and highly threatening phenomenon, is at best an exaggeration and at worst an utter "hoax," as James Inhofe of Oklahoma, the ranking Republican on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, once put it. These grim numbers, compiled by the Center for American Progress, describe a troubling new reality: the rise of the Tea Party and its anti-intellectual, anti-establishment, anti-elite worldview has brought both a mainstreaming and a radicalization of antiscientific thought.

- Matthews, Chris (May 12, 2014). "Hardball With Chris Matthews for May 12, 2014". Hardball With Chris Matthews. MSNBC. NBC News.

According to a survey by the Center for American Progress' Action Fund, more than 55 percent of congressional Republicans are climate change deniers. And it gets worse from there. They found that 77 percent of Republicans on the House Science Committee say they don't believe it in either. And that number balloons to an astounding 90 percent for all the party's leadership in Congress.

- "EARTH TALK: Still in denial about climate change". The Charleston Gazette. Charleston, West Virginia. December 22, 2014. p. 10.

...a recent survey by the non-profit Center for American Progress found that some 58 percent of Republicans in the U.S. Congress still "refuse to accept climate change. Meanwhile, still others acknowledge the existence of global warming but cling to the scientifically debunked notion that the cause is natural forces, not greenhouse gas pollution by humans.

- Kliegman, Julie (May 18, 2014). "Jerry Brown says 'virtually no Republican' in Washington accepts climate change science". PolitiFact. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- "RELEASE: CAP Action Releases 2017 Anti-Science Climate Denier Caucus". Center for American Progress Action Fund. April 28, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- Moser, Claire; Koronowski, Ryan (April 28, 2017). "The Climate Denier Caucus in Trump's Washington". ThinkProgress. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- Campo-Flores, Arian (June 12, 2019). "Some Republican Lawmakers Break With Party on Climate Change". WSJ. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- Sobczyk, Nick (July 26, 2019). "POLITICS: Young conservatives press GOP for climate reset". E&E News. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- "Green Party of the United States - National Committee Voting - Proposal Details". gp.org. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- "2016 Platform | Libertarian Party". Libertarian Party. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- "Platform Preamble". Constitution Party. 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- "Constitution Party on Energy & Oil". www.ontheissues.org. Retrieved 2017-04-24.