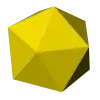

Regular icosahedron

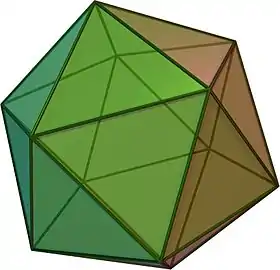

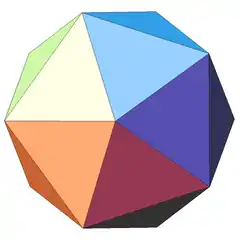

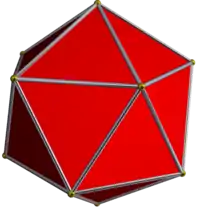

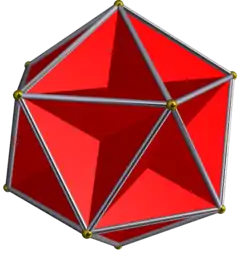

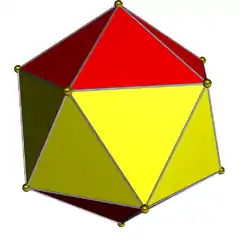

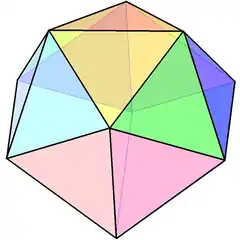

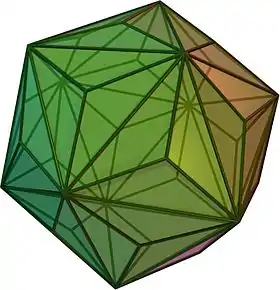

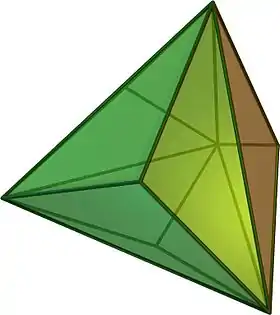

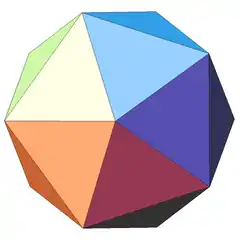

In geometry, a regular icosahedron (/ˌaɪkɒsəˈhiːdrən, -kə-, -koʊ-/ or /aɪˌkɒsəˈhiːdrən/[1]) is a convex polyhedron with 20 faces, 30 edges and 12 vertices. It is one of the five Platonic solids, and the one with the most faces.

| Regular icosahedron | |

|---|---|

(Click here for rotating model) | |

| Type | Platonic solid |

| Elements | F = 20, E = 30 V = 12 (χ = 2) |

| Faces by sides | 20{3} |

| Conway notation | I sT |

| Schläfli symbols | {3,5} |

| s{3,4} sr{3,3} or | |

| Face configuration | V5.5.5 |

| Wythoff symbol | 2 3 |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry | Ih, H3, [5,3], (*532) |

| Rotation group | I, [5,3]+, (532) |

| References | U22, C25, W4 |

| Properties | regular, convexdeltahedron |

| Dihedral angle | 138.189685° = arccos(−√5⁄3) |

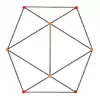

3.3.3.3.3 (Vertex figure) |

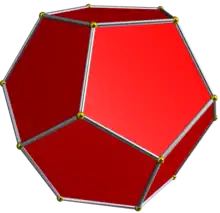

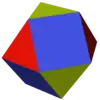

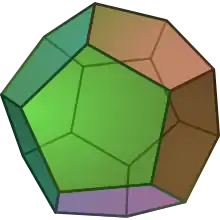

Regular dodecahedron (dual polyhedron) |

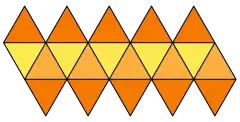

Net | |

It has five equilateral triangular faces meeting at each vertex. It is represented by its Schläfli symbol {3,5}, or sometimes by its vertex figure as 3.3.3.3.3 or 35. It is the dual of the dodecahedron, which is represented by {5,3}, having three pentagonal faces around each vertex.

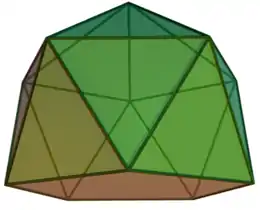

A regular icosahedron is a strictly convex deltahedron and a gyroelongated pentagonal bipyramid and a biaugmented pentagonal antiprism in any of six orientations.

The name comes from Greek εἴκοσι (eíkosi) 'twenty', and ἕδρα (hédra) 'seat'. The plural can be either "icosahedrons" or "icosahedra" (/-drə/).

Dimensions

If the edge length of a regular icosahedron is a, the radius of a circumscribed sphere (one that touches the icosahedron at all vertices) is

and the radius of an inscribed sphere (tangent to each of the icosahedron's faces) is

while the midradius, which touches the middle of each edge, is

where ϕ is the golden ratio.

Area and volume

The surface area A and the volume V of a regular icosahedron of edge length a are:

The latter is F = 20 times the volume of a general tetrahedron with apex at the center of the inscribed sphere, where the volume of the tetrahedron is one third times the base area √3a2/4 times its height ri.

The volume filling factor of the circumscribed sphere is:

- , compared to 66.49% for a dodecahedron.

A sphere inscribed in an icosahedron will enclose 89.635% of its volume, compared to only 75.47% for a dodecahedron.

The midsphere of an icosahedron will have a volume 1.01664 times the volume of the icosahedron, which is by far the closest similarity in volume of any platonic solid with its midsphere. This arguably makes the icosahedron the "roundest" of the platonic solids.

Cartesian coordinates

The vertices of an icosahedron centered at the origin with an edge-length of 2 and a circumradius of are described by circular permutations of:[2]

- (0, ±1, ±ϕ)

where ϕ = 1 + √5/2 is the golden ratio.

Taking all permutations (not just cyclic ones) results in the Compound of two icosahedra.

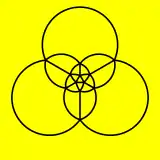

Note that these vertices form five sets of three concentric, mutually orthogonal golden rectangles, whose edges form Borromean rings.

If the original icosahedron has edge length 1, its dual dodecahedron has edge length √5 − 1/2 = 1/ϕ = ϕ − 1.

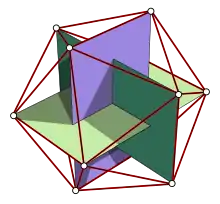

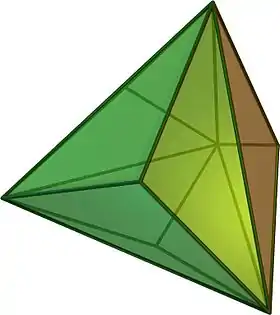

The 12 edges of a regular octahedron can be subdivided in the golden ratio so that the resulting vertices define a regular icosahedron. This is done by first placing vectors along the octahedron's edges such that each face is bounded by a cycle, then similarly subdividing each edge into the golden mean along the direction of its vector. The five octahedra defining any given icosahedron form a regular polyhedral compound, while the two icosahedra that can be defined in this way from any given octahedron form a uniform polyhedron compound.

Spherical coordinates

The locations of the vertices of a regular icosahedron can be described using spherical coordinates, for instance as latitude and longitude. If two vertices are taken to be at the north and south poles (latitude ±90°), then the other ten vertices are at latitude ±arctan(1/2) ≈ ±26.57°. These ten vertices are at evenly spaced longitudes (36° apart), alternating between north and south latitudes.

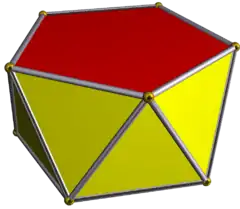

This scheme takes advantage of the fact that the regular icosahedron is a pentagonal gyroelongated bipyramid, with D5d dihedral symmetry—that is, it is formed of two congruent pentagonal pyramids joined by a pentagonal antiprism.

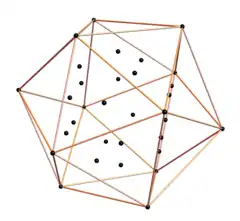

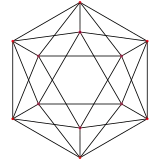

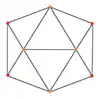

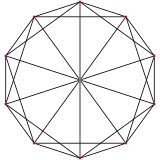

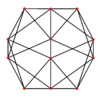

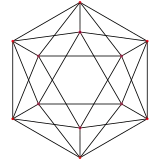

Orthogonal projections

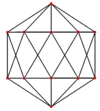

The icosahedron has three special orthogonal projections, centered on a face, an edge and a vertex:

| Centered by | Face | Edge | Vertex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coxeter plane | A2 | A3 | H3 |

| Graph |  |

|

|

| Projective symmetry |

[6] | [2] | [10] |

| Graph |  Face normal |

Edge normal |

Vertex normal |

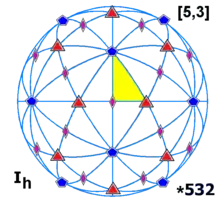

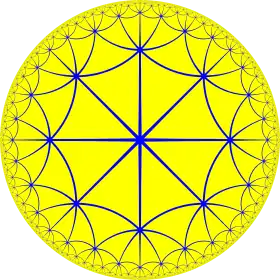

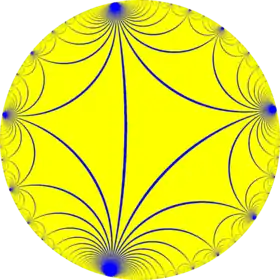

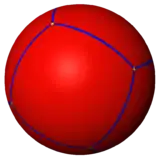

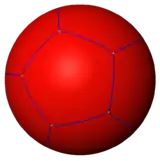

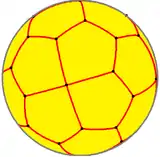

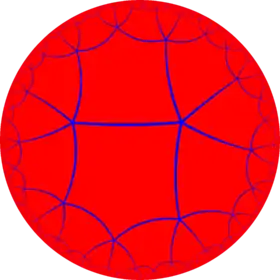

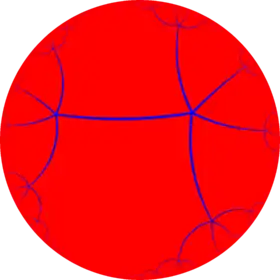

Spherical tiling

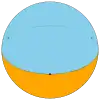

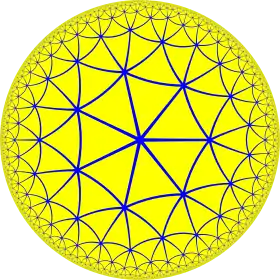

The icosahedron can also be represented as a spherical tiling, and projected onto the plane via a stereographic projection. This projection is conformal, preserving angles but not areas or lengths. Straight lines on the sphere are projected as circular arcs on the plane.

|

|

| Orthographic projection | Stereographic projection |

|---|

Other facts

- An icosahedron has 43,380 distinct nets.[3]

- To color the icosahedron, such that no two adjacent faces have the same color, requires at least 3 colors.[lower-alpha 1]

- A problem dating back to the ancient Greeks is to determine which of two shapes has larger volume, an icosahedron inscribed in a sphere, or a dodecahedron inscribed in the same sphere. The problem was solved by Hero, Pappus, and Fibonacci, among others.[4] Apollonius of Perga discovered the curious result that the ratio of volumes of these two shapes is the same as the ratio of their surface areas.[5] Both volumes have formulas involving the golden ratio, but taken to different powers.[6] As it turns out, the icosahedron occupies less of the sphere's volume (60.54%) than the dodecahedron (66.49%).[7]

Construction by a system of equiangular lines

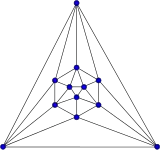

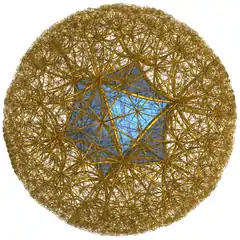

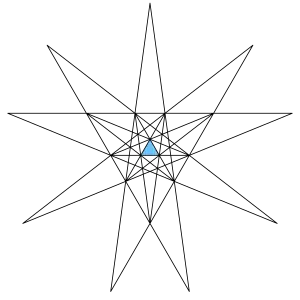

Icosahedron H3 Coxeter plane |

6-orthoplex D6 Coxeter plane |

| This construction can be geometrically seen as the 12 vertices of the 6-orthoplex projected to 3 dimensions. This represents a geometric folding of the D6 to H3 Coxeter groups: Seen by these 2D Coxeter plane orthogonal projections, the two overlapping central vertices define the third axis in this mapping. | |

The following construction of the icosahedron avoids tedious computations in the number field ℚ[√5] necessary in more elementary approaches.

The existence of the icosahedron amounts to the existence of six equiangular lines in ℝ3. Indeed, intersecting such a system of equiangular lines with a Euclidean sphere centered at their common intersection yields the twelve vertices of a regular icosahedron as can easily be checked. Conversely, supposing the existence of a regular icosahedron, lines defined by its six pairs of opposite vertices form an equiangular system.

In order to construct such an equiangular system, we start with this 6 × 6 square matrix:

A straightforward computation yields A2 = 5I (where I is the 6 × 6 identity matrix). This implies that A has eigenvalues –√5 and √5, both with multiplicity 3 since A is symmetric and of trace zero.

The matrix A + √5I induces thus a Euclidean structure on the quotient space ℝ6 / ker(A + √5I), which is isomorphic to ℝ3 since the kernel ker(A + √5I) of A + √5I has dimension 3. The image under the projection π : ℝ6 → ℝ6 / ker(A + √5I) of the six coordinate axes ℝv1, …, ℝv6 in ℝ6 forms thus a system of six equiangular lines in ℝ3 intersecting pairwise at a common acute angle of arccos 1⁄√5. Orthogonal projection of ±v1, …, ±v6 onto the √5-eigenspace of A yields thus the twelve vertices of the icosahedron.

A second straightforward construction of the icosahedron uses representation theory of the alternating group A5 acting by direct isometries on the icosahedron.

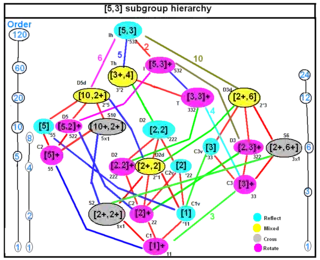

Symmetry

The rotational symmetry group of the regular icosahedron is isomorphic to the alternating group on five letters. This non-abelian simple group is the only non-trivial normal subgroup of the symmetric group on five letters. Since the Galois group of the general quintic equation is isomorphic to the symmetric group on five letters, and this normal subgroup is simple and non-abelian, the general quintic equation does not have a solution in radicals. The proof of the Abel–Ruffini theorem uses this simple fact, and Felix Klein wrote a book that made use of the theory of icosahedral symmetries to derive an analytical solution to the general quintic equation, (Klein 1884). See icosahedral symmetry: related geometries for further history, and related symmetries on seven and eleven letters.

The full symmetry group of the icosahedron (including reflections) is known as the full icosahedral group, and is isomorphic to the product of the rotational symmetry group and the group C2 of size two, which is generated by the reflection through the center of the icosahedron.

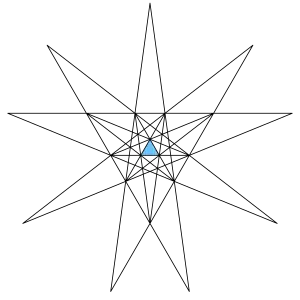

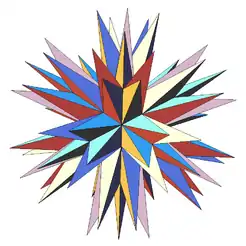

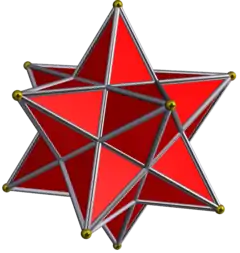

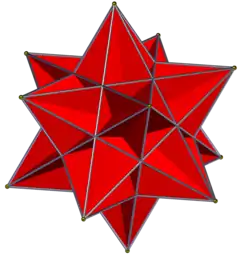

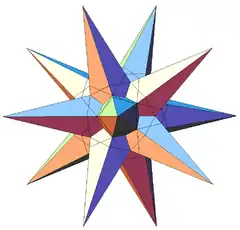

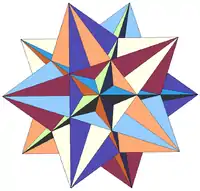

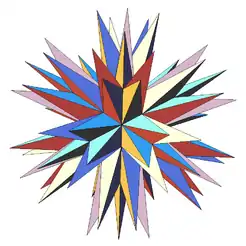

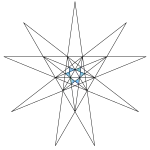

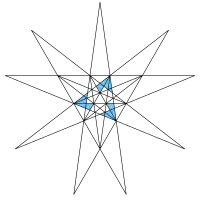

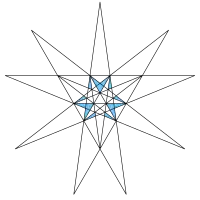

Stellations

The icosahedron has a large number of stellations. According to specific rules defined in the book The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra, 59 stellations were identified for the regular icosahedron. The first form is the icosahedron itself. One is a regular Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron. Three are regular compound polyhedra.[8]

The faces of the icosahedron extended outwards as planes intersect, defining regions in space as shown by this stellation diagram of the intersections in a single plane. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

Facetings

The small stellated dodecahedron, great dodecahedron, and great icosahedron are three facetings of the regular icosahedron. They share the same vertex arrangement. They all have 30 edges. The regular icosahedron and great dodecahedron share the same edge arrangement but differ in faces (triangles vs pentagons), as do the small stellated dodecahedron and great icosahedron (pentagrams vs triangles).

| Convex | Regular stars | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| icosahedron | great dodecahedron | small stellated dodecahedron | great icosahedron |

|

|

|

|

Geometric relations

There are distortions of the icosahedron that, while no longer regular, are nevertheless vertex-uniform. These are invariant under the same rotations as the tetrahedron, and are somewhat analogous to the snub cube and snub dodecahedron, including some forms which are chiral and some with Th-symmetry, i.e. have different planes of symmetry from the tetrahedron.

The icosahedron is unique among the Platonic solids in possessing a dihedral angle not less than 120°. Its dihedral angle is approximately 138.19°. Thus, just as hexagons have angles not less than 120° and cannot be used as the faces of a convex regular polyhedron because such a construction would not meet the requirement that at least three faces meet at a vertex and leave a positive defect for folding in three dimensions, icosahedra cannot be used as the cells of a convex regular polychoron because, similarly, at least three cells must meet at an edge and leave a positive defect for folding in four dimensions (in general for a convex polytope in n dimensions, at least three facets must meet at a peak and leave a positive defect for folding in n-space). However, when combined with suitable cells having smaller dihedral angles, icosahedra can be used as cells in semi-regular polychora (for example the snub 24-cell), just as hexagons can be used as faces in semi-regular polyhedra (for example the truncated icosahedron). Finally, non-convex polytopes do not carry the same strict requirements as convex polytopes, and icosahedra are indeed the cells of the icosahedral 120-cell, one of the ten non-convex regular polychora.

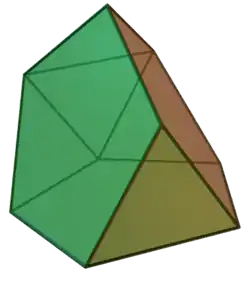

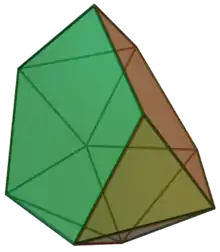

An icosahedron can also be called a gyroelongated pentagonal bipyramid. It can be decomposed into a gyroelongated pentagonal pyramid and a pentagonal pyramid or into a pentagonal antiprism and two equal pentagonal pyramids.

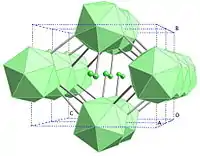

Relation to the 6-cube and rhombic triacontahedron

It can be projected to 3D from the 6D 6-demicube using the same basis vectors that form the hull of the Rhombic triacontahedron from the 6-cube. Shown here including the inner 20 vertices which are not connected by the 30 outer hull edges of 6D norm length √2. The inner vertices form a dodecahedron.

The 3D projection basis vectors [u,v,w] used are:

- u = (1, φ, 0, -1, φ, 0)

- v = (φ, 0, 1, φ, 0, -1)

- w = (0, 1, φ, 0, -1, φ)

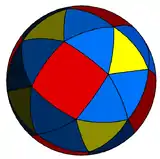

Uniform colorings and subsymmetries

There are 3 uniform colorings of the icosahedron. These colorings can be represented as 11213, 11212, 11111, naming the 5 triangular faces around each vertex by their color.

The icosahedron can be considered a snub tetrahedron, as snubification of a regular tetrahedron gives a regular icosahedron having chiral tetrahedral symmetry. It can also be constructed as an alternated truncated octahedron, having pyritohedral symmetry. The pyritohedral symmetry version is sometimes called a pseudoicosahedron, and is dual to the pyritohedron.

| Regular | Uniform | 2-uniform | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Regular icosahedron |

Snub octahedron |

Snub tetratetrahedron |

Snub square bipyramid |

Pentagonal Gyroelongated bipyramid |

Triangular gyrobianticupola |

Snub triangular antiprism[9] |

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Face coloring |

(11111) | (11212) | (11213) | (11212) | (11122) (22222) |

(12332) (23333) |

(11213) (11212) |

| Coxeter diagram |

|||||||

| Schläfli symbol |

{3,5} | s{3,4} | sr{3,3} | sdt{2,4} | () || {n} || r{n} || () | ss{2,6} | |

| Conway | I | HtO | sT | HtdP4 | k5A5 | sY3 = HtA3 | |

| Symmetry | Ih [5,3] (*532) |

Th [3+,4] (3*2) |

T [3,3]+ (332) |

D2h [2,2] (*222) |

D5d [2+,10] (2*5) |

D3d [2+,6] (2*3) |

D3 [3,2]+ (322) |

| Symmetry order |

60 | 24 | 12 | 8 | 20 | 12 | 6 |

Uses and natural forms

Biology

Many viruses, e.g. herpes virus, have icosahedral shells.[10] Viral structures are built of repeated identical protein subunits known as capsomeres, and the icosahedron is the easiest shape to assemble using these subunits. A regular polyhedron is used because it can be built from a single basic unit protein used over and over again; this saves space in the viral genome.

Various bacterial organelles with an icosahedral shape were also found.[11] The icosahedral shell encapsulating enzymes and labile intermediates are built of different types of proteins with BMC domains.

In 1904, Ernst Haeckel described a number of species of Radiolaria, including Circogonia icosahedra, whose skeleton is shaped like a regular icosahedron. A copy of Haeckel's illustration for this radiolarian appears in the article on regular polyhedra.

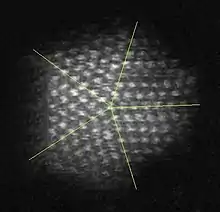

Chemistry

The closo-carboranes are chemical compounds with shape very close to icosahedron. Icosahedral twinning also occurs in crystals, especially nanoparticles.

Many borides and allotropes of boron contain boron B12 icosahedron as a basic structure unit.

Toys and games

_with_faces_inscribed_with_Greek_letters_MET_10.130.1158_001.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Icosahedral dice with twenty sides have been used since ancient times.[12]

In several roleplaying games, such as Dungeons & Dragons, the twenty-sided die (d20 for short) is commonly used in determining success or failure of an action. This die is in the form of a regular icosahedron. It may be numbered from "0" to "9" twice (in which form it usually serves as a ten-sided die, or d10), but most modern versions are labeled from "1" to "20".

An icosahedron is the three-dimensional game board for Icosagame, formerly known as the Ico Crystal Game.

An icosahedron is used in the board game Scattergories to choose a letter of the alphabet. Six letters are omitted (Q, U, V, X, Y, and Z).

In the Nintendo 64 game Kirby 64: The Crystal Shards, the boss Miracle Matter is a regular icosahedron.

Inside a Magic 8-Ball, various answers to yes–no questions are inscribed on a regular icosahedron.

Others

R. Buckminster Fuller and Japanese cartographer Shoji Sadao[13] designed a world map in the form of an unfolded icosahedron, called the Fuller projection, whose maximum distortion is only 2%. The American electronic music duo ODESZA use a regular icosahedron as their logo.

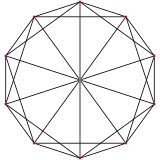

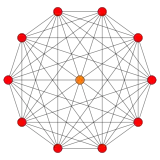

Icosahedral graph

| Regular icosahedron graph | |

|---|---|

3-fold symmetry | |

| Vertices | 12 |

| Edges | 30 |

| Radius | 3 |

| Diameter | 3 |

| Girth | 3 |

| Automorphisms | 120 (A5 × Z2) |

| Chromatic number | 4 |

| Properties | Hamiltonian, regular, symmetric, distance-regular, distance-transitive, 3-vertex-connected, planar graph |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

The skeleton of the icosahedron (the vertices and edges) forms a graph. It is one of 5 Platonic graphs, each a skeleton of its Platonic solid.

The high degree of symmetry of the polygon is replicated in the properties of this graph, which is distance-transitive and symmetric. The automorphism group has order 120. The vertices can be colored with 4 colors, the edges with 5 colors, and the diameter is 3.[14]

The icosahedral graph is Hamiltonian: there is a cycle containing all the vertices. It is also a planar graph.

|

Diminished regular icosahedra

There are 4 related Johnson solids, including pentagonal faces with a subset of the 12 vertices. The similar dissected regular icosahedron has 2 adjacent vertices diminished, leaving two trapezoidal faces, and a bifastigium has 2 opposite sets of vertices removed and 4 trapezoidal faces. The pentagonal antiprism is formed by removing two opposite vertices.

| Form | J2 | Bifastigium | J63 | J62 | Dissected icosahedron |

s{2,10} | J11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertices | 6 of 12 | 8 of 12 | 9 of 12 | 10 of 12 | 11 of 12 | ||

| Symmetry | C5v, [5], (*55) order 10 |

D2h, [2,2], *222 order 8 |

C3v, [3], (*33) order 6 |

C2v, [2], (*22) order 4 |

D5d, [2+,10], (2*5) order 20 |

C5v, [5], (*55) order 10 | |

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|

| |

Related polyhedra and polytopes

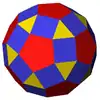

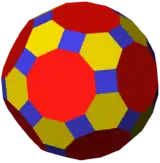

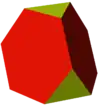

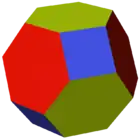

The icosahedron can be transformed by a truncation sequence into its dual, the dodecahedron:

| Family of uniform icosahedral polyhedra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [5,3], (*532) | [5,3]+, (532) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {5,3} | t{5,3} | r{5,3} | t{3,5} | {3,5} | rr{5,3} | tr{5,3} | sr{5,3} |

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | |||||||

|

|

|

|

| |||

| V5.5.5 | V3.10.10 | V3.5.3.5 | V5.6.6 | V3.3.3.3.3 | V3.4.5.4 | V4.6.10 | V3.3.3.3.5 |

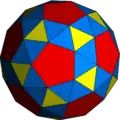

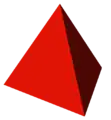

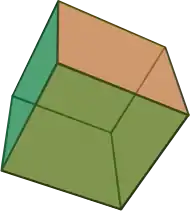

As a snub tetrahedron, and alternation of a truncated octahedron it also exists in the tetrahedral and octahedral symmetry families:

| Family of uniform tetrahedral polyhedra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [3,3], (*332) | [3,3]+, (332) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| {3,3} | t{3,3} | r{3,3} | t{3,3} | {3,3} | rr{3,3} | tr{3,3} | sr{3,3} |

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | |||||||

|

|

|

| ||||

| V3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3 | V3.4.3.4 | V4.6.6 | V3.3.3.3.3 |

| Uniform octahedral polyhedra | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry: [4,3], (*432) | [4,3]+ (432) |

[1+,4,3] = [3,3] (*332) |

[3+,4] (3*2) | |||||||

| {4,3} | t{4,3} | r{4,3} r{31,1} |

t{3,4} t{31,1} |

{3,4} {31,1} |

rr{4,3} s2{3,4} |

tr{4,3} | sr{4,3} | h{4,3} {3,3} |

h2{4,3} t{3,3} |

s{3,4} s{31,1} |

= |

= |

= |

||||||||

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | ||||||||||

| V43 | V3.82 | V(3.4)2 | V4.62 | V34 | V3.43 | V4.6.8 | V34.4 | V33 | V3.62 | V35 |

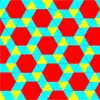

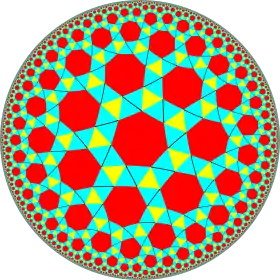

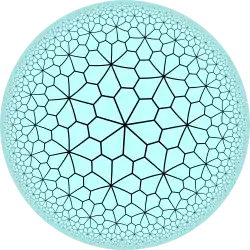

This polyhedron is topologically related as a part of sequence of regular polyhedra with Schläfli symbols {3,n}, continuing into the hyperbolic plane.

| *n32 symmetry mutation of regular tilings: {3,n} | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical | Euclid. | Compact hyper. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3.3 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 3∞ | 312i | 39i | 36i | 33i |

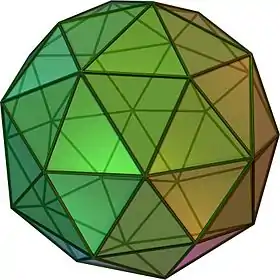

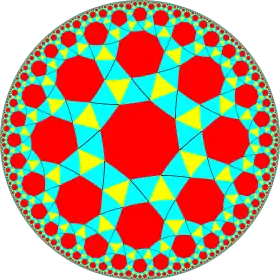

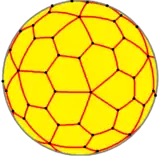

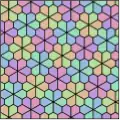

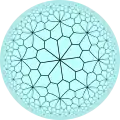

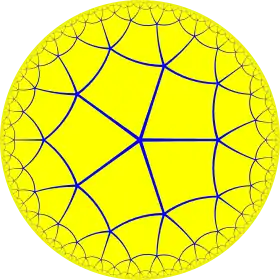

The regular icosahedron, seen as a snub tetrahedron, is a member of a sequence of snubbed polyhedra and tilings with vertex figure (3.3.3.3.n) and Coxeter–Dynkin diagram ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . These figures and their duals have (n32) rotational symmetry, being in the Euclidean plane for n = 6, and hyperbolic plane for any higher n. The series can be considered to begin with n = 2, with one set of faces degenerated into digons.

. These figures and their duals have (n32) rotational symmetry, being in the Euclidean plane for n = 6, and hyperbolic plane for any higher n. The series can be considered to begin with n = 2, with one set of faces degenerated into digons.

| n32 symmetry mutations of snub tilings: 3.3.3.3.n | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry n32 |

Spherical | Euclidean | Compact hyperbolic | Paracomp. | ||||

| 232 | 332 | 432 | 532 | 632 | 732 | 832 | ∞32 | |

| Snub figures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Config. | 3.3.3.3.2 | 3.3.3.3.3 | 3.3.3.3.4 | 3.3.3.3.5 | 3.3.3.3.6 | 3.3.3.3.7 | 3.3.3.3.8 | 3.3.3.3.∞ |

| Gyro figures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Config. | V3.3.3.3.2 | V3.3.3.3.3 | V3.3.3.3.4 | V3.3.3.3.5 | V3.3.3.3.6 | V3.3.3.3.7 | V3.3.3.3.8 | V3.3.3.3.∞ |

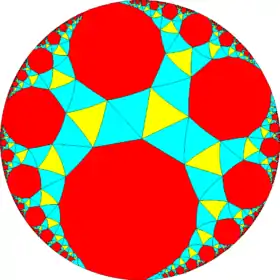

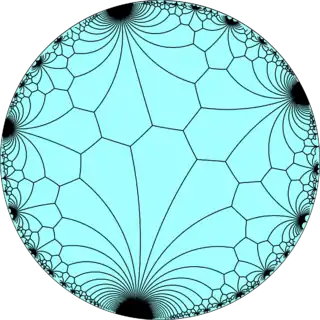

| Spherical | Hyperbolic tilings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

{2,5} |

{3,5} |

{4,5} |

{5,5} |

{6,5} |

{7,5} |

{8,5} |

... |  {∞,5} |

The icosahedron can tessellate hyperbolic space in the order-3 icosahedral honeycomb, with 3 icosahedra around each edge, 12 icosahedra around each vertex, with Schläfli symbol {3,5,3}. It is one of four regular tessellations in the hyperbolic 3-space.

It is shown here as an edge framework in a Poincaré disk model, with one icosahedron visible in the center. |

See also

- Great icosahedron

- Geodesic grids use an iteratively bisected icosahedron to generate grids on a sphere

- Icosahedral twins

- Infinite skew polyhedron

- Jessen's icosahedron

- Regular polyhedron

- Truncated icosahedron

Notes

- This is true for all convex polyhedra with triangular faces except for the tetrahedron, by applying Brooks' theorem to the dual graph of the polyhedron.

References

- Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Icosahedral group". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Regular Icosahedron". MathWorld.

- Herz-Fischler, Roger (2013), A Mathematical History of the Golden Number, Courier Dover Publications, pp. 138–140, ISBN 9780486152325.

- Simmons, George F. (2007), Calculus Gems: Brief Lives and Memorable Mathematics, Mathematical Association of America, p. 50, ISBN 9780883855614.

- Sutton, Daud (2002), Platonic & Archimedean Solids, Wooden Books, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, p. 55, ISBN 9780802713865.

- Numerical values for the volumes of the inscribed Platonic solids may be found in Buker, W. E.; Eggleton, R. B. (1969), "The Platonic Solids (Solution to problem E2053)", American Mathematical Monthly, 76 (2): 192, doi:10.2307/2317282, JSTOR 2317282.

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald; Du Val, P.; Flather, H.T.; Petrie, J.F. (1999), The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra (3rd ed.), Tarquin, ISBN 978-1-899618-32-3, MR 0676126 (1st Edn University of Toronto (1938))

- Snub Anti-Prisms

- C. Michael Hogan. 2010. Virus. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. eds. S. Draggan and C. Cleveland

- Bobik, T.A. (2007), "Bacterial Microcompartments", Microbe, Am. Soc. Microbiol., 2: 25–31, archived from the original on 2013-07-29

- Cromwell, Peter R. "Polyhedra" (1997) Page 327.

- "Fuller and Sadao: Partners in Design". September 19, 2006. Archived from the original on August 16, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Icosahedral Graph". MathWorld.

- Klein, Felix (1888), Lectures on the ikosahedron and the solution of equations of the fifth degree, ISBN 978-0-486-49528-6, Dover edition, translated from Klein, Felix (1884). Vorlesungen über das Ikosaeder und die Auflösung der Gleichungen vom fünften Grade. Teubner.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Icosahedron. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Icosahedron. |

| Look up icosahedron in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Klitzing, Richard. "3D convex uniform polyhedra x3o5o – ike".

- Hartley, Michael. "Dr Mike's Math Games for Kids".

- K.J.M. MacLean, A Geometric Analysis of the Five Platonic Solids and Other Semi-Regular Polyhedra

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra

- Tulane.edu A discussion of viral structure and the icosahedron

- Origami Polyhedra – Models made with Modular Origami

- Video of icosahedral mirror sculpture

- Principle of virus architecture

| Notable stellations of the icosahedron | |||||||||

| Regular | Uniform duals | Regular compounds | Regular star | Others | |||||

| (Convex) icosahedron | Small triambic icosahedron | Medial triambic icosahedron | Great triambic icosahedron | Compound of five octahedra | Compound of five tetrahedra | Compound of ten tetrahedra | Great icosahedron | Excavated dodecahedron | Final stellation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| The stellation process on the icosahedron creates a number of related polyhedra and compounds with icosahedral symmetry. | |||||||||