Dervish movement (Somali)

The Somali Dervish movement (Somali: Halgankii Daraawiishta) was a popular movement that developed in Somaliland between 1899 and 1920 that called for the expulsion of all foreign powers from the Somaliland region in the Horn of Africa.[2][3] It was led by the Salihiyya Sufi Muslim poet and militant leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, also known as Sayyid Mohamed, who called for the removal of British and Italian colonies in Somalia, the defeat of Ethiopian forces, the expulsion of Christianity and the establishment of a Muslim Somali state.[2][3] Hassan established a ruling council called the Khususi consisting of Islamic clan leaders and elders, added an adviser from the Ottoman Empire named Muhammad Ali and thus created a multi-clan Islamic movement in what led to the eventual creation of the state of Somalia.[3][2][4]

Somali Dervish movement Halgankii Daraawiishta | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1899–1920 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Taleh | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam with Sufism-orientation | ||||||||||

| Mullah, Sayid[1] | |||||||||||

• 1899-1920 | Mohammed Abdullah Hassan | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1899 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 9 February 1920 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

The Dervish movement attracted between 5,000 and 6,000 youth from different clans over 1899 and 1900, acquired firearms and then attacked the Ethiopian army in the Jigjiga region. The Ethiopians retreated and then gave the Dervishes their first military victory.[5][note 1] The Dervish movement then declared the colonial administration in British Somaliland as their enemy. To end the movement, the British sought out the competing Somali clans as coalition partners against the Dervish movement. The British provided these clans with firearms and supplies to fight against the Dervishes. Punitive attacks were launched against Dervish strongholds in 1904.[2][3] The Dervish movement suffered losses in the field, regrouped into smaller units and resorted to guerrilla warfare. Hasan and his loyalist Dervishes moved into the Italian-controlled Somaliland in 1905, where Hasan signed the Illig treaty and thereafter strengthened his movement.[2] In 1908, the Dervishes entered the British Somaliland again and began inflicting major losses to the British in the interior regions of the Horn of Africa. The British retreated to the coastal regions, leaving the chaotic interior regions in the hands of the Dervishes. The First World War shifted the attention of the British elsewhere, although upon its conclusion, in 1920 the British launched a massive combined arms offensive on the Taleh forts strongholds of the Dervish movement.[3][5] The offensive caused significant casualties among the Dervishes, although the Dervish leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan managed to escape. His death in 1921 due to either malaria or influenza ended the Dervish movement.[2][3][7]

The Dervish movement temporarily created a mobile Somali "proto-state" in early 20th-century with fluid boundaries and fluctuating population.[8] It was one of the bloodiest and longest militant movements in sub-Saharan Africa during the colonial era, one that overlapped with World War I. The battles between various sides over two decades killed nearly a third of Somaliland's population and ravaged the local economy.[7][9][10] Scholars variously interpret the emergence and demise of the militant Dervish movement in Somalia. Some consider the "Sufi Islamic" ideology as the driver, others consider economic crisis to the nomadic lifestyle triggered by the occupation and "colonial predation" ideology as the trigger for the Dervish movement, while post-modernists state that both religion and nationalism created the Dervish movement.[3]

History

Origins

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somalia |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somaliland |

|

|

|

According to Abdullah A. Mohamoud, traditional Somali society followed a decentralized structure and a nomadic lifestyle dependent on livestock and pastureland. It was also predominantly Muslim.[2][3] As the European colonial powers expanded their reach in the Horn of Africa, the region of Somalia came under the influence of the Ethiopians, the British and the Italians. With foreign rule came the centralization of the economy, which greatly upset the traditional lifestock and pastureland based livelihood of the Somalis. The foreign powers were also all Christians, which created additional suspicions amongst the Somali religious elite.[3] The Ethiopian troops had already proved to be a bane for the Somalis as they were the traditional raiders and plunderers of their grazing herds. The arrival of the colonial powers and the consequent partitioning of Africa greatly affected the Somalis, with Sufi poets such as Faarax Nuur writing poems expressing his opposition to foreign rule.[11] The Dervish movement can thus be seen as a reaction against the establishment of foreign control in Ethiopia.[3]

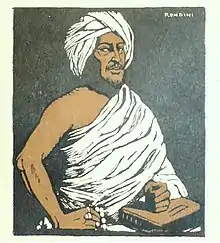

The Dervish movement was led by a Sufi poet and religious nationalist leader named Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, also known as Sayid Maxamad Cabdulle Xasan.[2] According to Said M. Mohamed, he was born in Sacmadeeqo sometime between 1856 and 1864 to a father who was a religious teacher.[2] He studied in Somali Islamic seminaries and later went on Hajj to Mecca where he met Shaykh Muhammad Salah of the Salihiya Islamic Tariqah, which states The Encyclopedia Britannica was a "militant, reformist, and puritanical Sufi order".[12][2] The preachings of Salah to Hasan had roots in Saudi Wahhabism, and it considered it a religious duty "to wage a holy war (jihad) against all other forms of Islam, the Western and Christian presence in the Muslim world, and a religious revival", state Richard Shultz and Andrea Dew.[7] When Hasan returned to the Horn of Africa, the Somali tradition states that he saw Somali children being converted to Christianity by missionaries in the British colony. Hasan began preaching against this religious conversion and the British presence. He earned the ire of the British colonial administration who termed him the 'mad mullah', and his Sufi teachings were also opposed by the rival Qadiriya Tariqah – another traditional Sufi group of the region, states Said M. Mohamed.[2][13] Another version of the early events link the illegal sale of a gun to Hasan by a corrupt Somali officer in 1899, who reported his gun as stolen rather than purchased by Hasan.[14] The British authorities demanded the gun's return, while Hasan replied that the British should leave the country, a sentiment he had previously claimed in 1897 when he declared himself "the leader of a sovereign nation".[14] Hasan continued to preach against the British introduction of Christianity to Somalia, stating that the "British infidels have destroyed our [Islamic] religion and made our children their children"..[14]

Hasan left the urban settlement and moved to preach in the countryside. His influence spread in the rural parts and many elders, as well as youth, became his followers. Hasan converted the influenced youth from different clans into a Muslim brotherhood,[12] rallying to protect Islam from the influence of the Christian missionaries.[15] These formed the Hasan's armed resistance group to confront the colonial powers, and came to be known as Dervishes or Daraawiish, states Said M. Mohamed.[2]

Movement

The Dervish movement temporarily created a Somali "proto-state", according to Markus Hoehne.[8] It was a mobile state with fluid boundaries and fluctuating population given the guerilla style militant approach of Dervishes and their practice of retreating to sparsely inhabited hinterland whenever the colonial forces with superior firearms overwhelmed them. At the head of this state was the Sufi leader Hasan with the power of final decision. Hasan surrounded himself with a group of commanders for the militant operations supported by the khusuusi or the Dervish council. Islamic judges settled disputes and enforced the Islamic law in this Dervish state. According to Robert Hess, two of Hasan's chief advisors were Sultan Nur – previously Habr Yunis chief, and Haji Sudi Shabeel also known as Ahmad Warsama from Adan Madoba Habr Je'lo who was fluent in English.[16][17]

The constituent clans of the Dervish during the formative years belonged to sections of the Ogaden, Dhulbahante, Habr Je'lo and Habr Yunis clans:

He acquired some notoriety by seditious preaching in Berbera in 1895, after which he returned to his tariga in Kob Faradod, in the Dolbahanta. Here he gradually acquired influence by stopping inter-tribal warfare, and eventually started a religious movement in which the Rer Ibrahim (Mukahil Ogaden), Ba Hawadle (Miyirwalal Ogaden) and the Ali Gheri (Dolbahanta) were the first to join. His emissaries also soon succeeded in winning over the Adan Madoba, notable amongst whom was Haji Sudi, his trusted lieutenant, and the Ahmed Farih and Rer Yusuf, all Habr Toljaala, and the Musa Ismail of the Eastern Habr Yunis, Habr Gerhajis, with Sultan Nur.[18]

Between 1900 and 1913, they operated from temporary local centers such as Aynabo and Illig in Somaliland.[8]

The Dervishes wore white turban and its army utilized horses for movement. They assassinated opposing clan leaders.[8] Dervish soldiers used the dhaanto and geeraar traditional dance-song to raise their esprit de corps and sometimes sang it on horseback.[19] Hasan commanded the Dervish movement soldiers in a martial manner, ensuring that they were religiously committed, powered up for warfare and men of character sworn with an oath of allegiance.[7] To ensure unity among his troops, instead of letting them identify themselves by their different tribes, he made them identify themselves uniformly as Dervish.[20] The movement obtained firearms from Sultan Boqor Osman Mahmud of Majerteen Sultanate, as well as the Ottoman Empire and Sudan. In addition, the Dervishes also obtained significant armaments' from the Adan Madoba section of the Habr Je'lo clan where, according to the contemporary source Official History of the Operations in Somaliland: "Of the former the Adan Madoba were not only responsible for supplying him Abdullah Hassan with arms, but also assisted him on all his raids."[21][14] The Dervish fought many battles starting in 1899 against the Ethiopian troops.[7] In 1904, the Dervishes were almost annihilated in Jidbaley. Hasan retreated into the Italian Somaliland and entered into a treaty with them, who accepted the control of Eyl port by the Dervishes. This port served as the Dervish headquarters between 1905 and 1909.[8] During this period, Hasan rebuilt the Dervish movement army, the Dervishes raided and plundered their neighboring clans, and in 1909 assassinated their archrival Sufi leader Uways al-Barawi and burnt his settlement, according to Mohamed Mukhtar.[22]

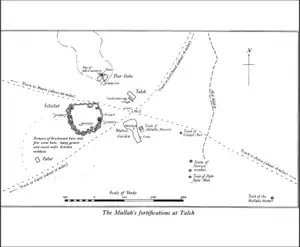

In 1913, after the British withdrawal to the coast, the Dervishes created a walled town with fourteen fortresses in Taleh by importing masons from Yemen. This served as their headquarters.[23][24] The main fortress, Silsilat, included conical tower granaries that opened only at the top, wells with sulfurous water, cattle watering stations, a guard tower, walled garden, and tombs. It became the residence of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, his wives and family.[23] The Taleh structures also included the Hed Kaldig (literally, "place of blood"), where those whom Hasan disliked were executed with or without torture and their bodies left to the hyenas.[23] According to Muktar, Hasan's execution orders also targeted dozens of his former friends and allies.[22] The town of Taleh was mostly destroyed after a RAF aerial bombardment in early February 1920, though Hasan had already left his compound by then.[23][25]

The Dervish movement aimed to remove the British and Italian influence from the region and restore the "Islamic system of government with Islamic education as its foundation", according to Mohamed-Rahis Hasan and Salada Robleh.[26]

Banadir Resistance

In southern Somalia, there was another resistance, the Bimal or Banadir Resistance. This was a large resistance lead by the Bimal clan spanning 3 decades of war. The Bimal being the main element, eventually neighboring adjacent tribes also joined the Bimal their struggle against the Italians. The Italians feared that the Banadir Resistance would join hands with the Somali Dervish Movement in the north. The Sayyid and leader of the Dervishes even sent an extensive letter to the Bimal.

Risala lil-Bimal

His letter to the Bimal was documented as the most extended exposition of his mind as a Muslim thinker and religious figure. The letter is till this day still preserved. It is said that the Bimal thanks to their size being numerically powerful, traditionally and religiously devoted fierce warriors and having possession of much resources have intrigued Mahamed Abdulle Hassan. But not only that the Bimal themselves mounted a extensive and major resistance against the Italians, especially in the first decade of the 19th century. The Italians carried many expeditions against the powerful Bimal to try and pacify them. Because of this the Bimal had all the reasons to join the Dervish struggle and by doing so to win their support over the Sayyid wrote a detailed theological statement to put forward to the Bimal tribe who dominated the strategic Banaadir port of Merca and its surroundings.[27]

One of the Italian`s greatest fears was the spread of 'Dervishism' ( had come to mean revolt) in the south and the strong Bimaal tribe of Benadir whom already were at war with the Italians, while not following the religious message or adhering to the views of Muhammad Abdullah Hassan, understood greatly his goal and political tactics. The dervishes in this case were engaged in supplying arms to the Bimaal.[28] The Italians wanted to bring in an end to the Bimaal revolt and at all cost prevent a Bimal-Dervish alliance, which lead them to use the forces of Obbia and the Mijertein as prevention.[28]

Wars against the British Empire, Italy and Ethiopia

In August 1898, the Dervish army occupied Burao, an important centre of British Somaliland, giving Muhammad Abdullah Hassan control over the city's watering places. Hassan also succeeded in making peace between the local clans and initiated a large assembly, where the population was urged to join the war against the British. His forces were supplied with the simple uniforms consisting of "a white cotton outer garment (worn by most Somali men of the time anyway), a white turban, a tasbih (or rosary), and a rifle."[29]

In March 1900, Hassan along with his dervish forces attacked an Ethiopian outpost near Jijiga. Capt. Malcolm McNeill who commanded the Somali Field Force against Hassan reported that the Dervish were completely defeated, and that they have suffered a heavy loss amounting to 2,800 killed, according to the Ethiopians.[30] Similar raids by the dervish would continue despite the losses across the Somali peninsula until 1920. McNeill notes that by June 1900, Hassan made his position even stronger than before his March 1900 defeat and had “practically dominated the whole of the southern portion of our Protectorate”.[30]

The British administration started to coordinate with the Italians and Ethiopians , and by 1901 a joint Anglo-Ethiopian force began to coordinate plans to eradicate the jihadists or limit their reach farther west to the Ogaden or borderland of northern Kenya. Lack of supplies and access to fresh drinking water in the large expanse of flat land made this a challenging feat for the British and their allies. In contrast, Hassan and his dervishes adapted harsh conditions of the land by eating carcasses of beasts and drinking water from the dead bellies of animals.[30] Despite possessing superior weapons, including Maxim machine guns, until 1905, the Anglo-Ethiopian forces were still struggling to gain hold on the dervish movement.

Britain launched at least two major offensives aimed at either killing or capturing Hassan between 1913 and 1920. Though they almost succeeded, Hassan proved elusive. Finally, the British Cabinet approved of air operations against the Dervish movement. It is said that the challenge of the Dervishes presented the British with a suitable environment to trial its new doctrine of warfare, which stressed "the use of aircraft as the primary arm, usually supplemented by ground forces, according to particular requirements."[31]

In the Somaliland campaign of 1920, 12 Airco DH.9A aircraft were used to support the British forces. Within a month, the British had occupied the capital of the Dervish State and Hassan had retreated to the west.[31]

Modern legacy

The Dervish legacy in Somalia and Somaliland has been influential. It was the "most important revivalist Islamic movements" in Somalia, state Hasan and Robleh.[32] The movement and particularly its leader has been controversial in Somalia. Some cherish it as the founder of modern Somali nationalism, while some others view it as an ambitious Muslim brotherhood militancy that destroyed Somalia's opportunity to move towards modernization and progress in favor of a puritanical Islamic state embedded with Islamic education – ideas enshrined in the contemporary constitution of Somalia.[32] Yet others such as Aidid consider the Dervish legacy was one of cruelty and violence against those Somalis who disagreed with or refused to submit to Hasan. These Somalis were "declared Kufr" and Dervish soldiers were ordered by Hasan to "kill them, their children and women and snatch all their property", according to Shultz and Dew.[7][33] Another legacy that came out of the prolonged struggle and violence between the colonial powers and the Dervish movement, according to Abdullah A. Mohamoud, was the arming of the Somali clans followed by decades of destructive clan-driven militarism, violent turmoil, and high human costs well after the demise of the Dervish movement.[3][34]

Hasan and his Dervish movement have inspired a nationalistic following in contemporary Somalia.[35][36] The military government of Somalia led by Mohamed Siad Barre, for example, erected statues visible between Makka Al Mukarama and Shabelle Roads in the heart of Mogadishu. These were for three major Somali History icons: Mohammed Abdullah Hassan of the Dervish movement, Stone Thrower and Hawo Tako. The castles and fortresses built by the Dervishes were included in a list of Somalia's national treasures. The Dervish period spawned many war poets and peace poets involved in a struggle known as the Literary war which had a profound effect on Somali poetry and Literature, with Mohammed Abdullah Hassan featuring as the most prominent poet of that Age.[37] Many of these poems continue to be taught in Somali schools and have been recited by several Presidents of Somalia in speeches as well as in poetry competitions. In Somali Studies, the Dervish period is an important chapter in Somalia's history and its brief period of European hegemony, the latter of which inspired the resistance movement. Due to their goal of creating a unified Somali State or Greater Somalia transcending regional and clan divisions, many scholars regard the Dervishes as the ideological architects of Somalia[38] and Muhammad Abdullah Hassan himself as the "Father of the Nation".[39]

See also

Notes

- The term Dervish, states Abdullah A. Mohamoud citing Beachey, has origins in the Turkish dervi or Persian darvesh. It means "ardent fighters for Islam" with an austere lifestyle.[6]

References

- ʻAbdi ʻAbdulqadir Sheik-ʻAbdi (1993). Divine madness: Moḥammed ʻAbdulle Ḥassan (1856-1920). Zed Books. p. 67. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong; Mr. Steven J. Niven (2012). Dictionary of African Biography. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. pp. 60–61, 70–72 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 27.

- Abdi Ismail Samatar (1989). The State and Rural Transformation in Northern Somalia, 1884-1986. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-299-11994-2.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. p. 71 with footnote 81. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Richard H. Shultz; Andrea J. Dew (2009). Insurgents, Terrorists, and Militias: The Warriors of Contemporary Combat. Columbia University Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-231-12983-1.

- Markus V. Hoehne (2016). John M Mackenzie (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe069. ISBN 978-11184-406-43.

- Michel Ben Arrous; Lazare Ki-Zerbo (2009). African Studies in Geography from Below. African Books. p. 166. ISBN 978-2-86978-231-0.

- Robert L. Hess (1964). "The 'Mad Mullah' and Northern Somalia". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 5 (3): 415–433. doi:10.1017/S0021853700005107. JSTOR 179976.

- Abdullah A. Mohamoud (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. pp. 70 with footnote 79. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- Sayyid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan, Encyclopedia Britannica

- David Motadel (2014). Islam and the European Empires. Oxford University Press. pp. 17–18 with footnotes 49–50, 165–166. ISBN 978-0-19-966831-1.

- Raphael Chijioke Njoku (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-313-37857-7.

- Benjamin Hopkins (2014). David Motadel (ed.). Islam and the European Empires. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-19-966831-1., Quote: "Men of religious learning and authority were well-positioned in these societies [Somaliland, Sudan, Northwest Frontier of British India] to straddle the disparate and often conflicting interests of local peoples. The protection of Islam became their rallying cry, providing a coherent narrative of and justification for resistance against the forces of colonialism, as well as a unifying force which superseded particularist tribal identities."

- Robert L. Hess (1968). Norman Robert Bennett (ed.). Leadership in Eastern Africa: Six Political Biographies. Boston University Press. p. 103.

- R. W. Beachey (1990). The warrior mullah: the Horn aflame, 1892-1920. Bellew. pp. 37–44. ISBN 978-0-947792-43-5.

- Official History of the Operations in Somaliland, 1901-04. H. M. Stationery office. p. 49.

- Johnson, John William (1996). Heelloy: Modern Poetry and Songs of the Somali. Indiana University Press. p. 31. ISBN 1874209812.

- Saadia Touval (1963). Somali nationalism: international politics and the drive for unity in the Horn of Africa. Harvard University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780674818255.

- Official History of the Operations in Somaliland, 1901-04. H. M. Stationery office. p. 41.

- Mohamed Haji Mukhtar (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- W. A. MacFadyen (1931), Taleh, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 125–128

- Robert L. Hess (1968). Norman Robert Bennett (ed.). Leadership in Eastern Africa: Six Political Biographies. Boston University Press. pp. 90–97.

- Michael Napier (2018). The Royal Air Force: A Centenary of Operations. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-4728-2539-1.

- Hasan, Mohamed-Rashid S., and Salada M. Robleh (2004), "Islamic revival and education in Somalia", Educational Strategies Among Muslims in the Context of Globalization: Some National Case Studies, Volume 3, BRILL Academic, page 147

- Samatar, Said S. (1992). In the Shadow of Conquest: Islam in Colonial Northeast Africa. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-70-7.

- Hess, Robert L. (1964-01-01). "The 'Mad Mullah' and Northern Somalia". The Journal of African History. 5 (3): 415–433, page 422. doi:10.1017/s0021853700005107. JSTOR 179976.

- Martin, B. G. (2003-02-13). Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521534512.

- Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313378577.

- Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313378577.

- Hasan, Mohamed-Rashid S., and Salada M. Robleh (2004), "Islamic revival and education in Somalia", Educational Strategies Among Muslims in the Context of Globalization: Some National Case Studies, Volume 3, BRILL Academic, pages 143, 146-148, 150-152

- Kimberly A. Huisman (2011). Kimberly A. Huisman; Mazie Hough; et al. (eds.). Somalis in Maine: Crossing Cultural Currents. North Atlantic Books. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-55643-926-1.

- Rebecca Richards (2016). Understanding Statebuilding: Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland. Routledge. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-317-00466-0.

- Lotje de Vries; Pierre Englebert; Mareike Schomerus (2018). Secessionism in African Politics: Aspiration, Grievance, Performance, Disenchantment. Springer International. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-3-319-90206-7.

- Said S. Samatar (1982). Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism: The Case of Sayid Mahammad 'Abdille Hasan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–24, 72–73. ISBN 978-0-521-23833-5.

- SOMALIA: A Nation's Literary Death Tops Its Political Demise by Said S Samatar

- Pg 393 – Literatures in African Languages: Theoretical Issues and Sample Surveys By B. W. Andrzejewski, S. Pilaszewicz, W. Tyloch

- Pg 187 – The Soviet Union in the Horn of Africa: the diplomacy of intervention and Disengagement By Robert G. Patman