Tazewell County, Virginia

Tazewell County is a county located in the southwestern portion of the U.S. state of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 45,078.[2] Its county seat is Tazewell.[3]

Tazewell County | |

|---|---|

Tazewell County Courthouse | |

Seal | |

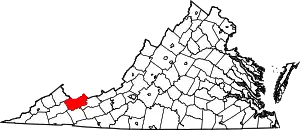

Location within the U.S. state of Virginia | |

Virginia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 37°08′N 81°34′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | December 20, 1799 |

| Named for | Henry Tazewell |

| Seat | Tazewell |

| Largest town | Richlands |

| Area | |

| • Total | 520 sq mi (1,300 km2) |

| • Land | 519 sq mi (1,340 km2) |

| • Water | 1.1 sq mi (3 km2) 0.2% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 45,078 |

| • Estimate (2018)[1] | 40,855 |

| • Density | 87/sq mi (33/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 9th |

| Website | tazewellcountyva |

Tazewell County is part of the Bluefield, WV-VA Micropolitan Statistical Area. Its economy was dependent on coal and iron of the Pocahontas Fields from the late 19th into the 20th century.

History

Tazewell County was long a hunting ground for various historic Native American tribes and their ancestral indigenous cultures. Although rare in the eastern United States, there are petroglyphs near the summit of Paintlick Mountain.[4] Among the tribes that occupied this area in historic times were the Lenape (Delaware), and the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee and members of the Iroquois Confederacy.

In the spring of 1771, Thomas and John Witten established the first permanent settlement in Tazewell County at Crab Orchard.[5]

As population increased in the area, Tazewell County was created on December 20, 1799. The land for the county was taken from portions of Wythe and Russell counties. It was named after Henry Tazewell, a United States Senator from Virginia, state legislator and judge. Delegate Littleton Waller Tazewell originally opposed the formation of the new county but when Simon Cotterel, who drew up the bill to form the county, changed the originally proposed name of the county to Tazewell's namesake, in honor of his father Henry who had died earlier that year, the bill passed.[6]

Jeffersonville was established the following year (1800) as the county seat. On February 29, 1892, Jeffersonville was renamed as Tazewell.

During the early settlement period, many Scots-Irish settled through the Appalachian backcountry, including here and in what is now West Virginia. They tended to be yeoman farmers, owning fewer slaves than the planters in the Tidewater or some Piedmont areas. They developed separate goals and political culture from eastern residents. During the American Civil War, West Virginia, which had many Union supporters, seceded from Virginia and the Confederacy, and was admitted to the Union as an independent state.

Post-Reconstruction era to present

Tazewell County has long been overwhelmingly white in population. In the post-Reconstruction and late 19th century period, when the state imposed Jim Crow, Tazewell County had an unusually high level of lynchings of blacks compared to the rest of Virginia. According to the Equal Justice Institute's report of lynchings in the South from 1877 to 1950, there were 10 lynchings in the county in this period, far exceeding the number in most other counties in the state, which had one or two. Most occurred during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, during the period of the coal boom and rapid social change in the region.[7] Danville County had the second-highest total in the state, with five lynchings in this period.[8][7] The last lynching in the state took place in Wytheville in 1926. In the early 20th century, Virginia had passed a new constitution disenfranchising most blacks.[7]

Construction of railroads in southwestern Virginia enabled the development of coal and iron resources in the Clinch Valley. The railroads and coal industry attracted new workers for industrial jobs, including blacks from other rural areas of the South and immigrants from Europe, which resulted in social tensions. Richlands had a boom economy in the early 1890s, and became a rougher place with young industrial workers and more saloons. Many whites resisted the entry of blacks into southwestern Virginia.

The profits generated by the coal boom resulted in the development of mansions and the elaborate Richlands Hotel, said to rival the best hotels of New York City. But it was forced to close after the boom cycle ended. It was used for other purposes.[9]

Samuel Garner was lynched in the town of Bluefield (then known as Graham) on September 16, 1889.[10]

On February 1, 1893, five black railroad workers were lynched in Richlands.[7] Four of the men had allegedly been drinking the night before with two white store owners, in the presence of a "disreputable white woman", and were accused of later robbing and beating the whites.[11] The black men were arrested the next day, and the sheriff turned them over to a mob of nearly 80 whites who had quickly formed. The mob conducted a mass hanging of the four that day, before any trial could take place. Prominent townsmen were leaders, including "James Hurt, a magistrate and member of the ... town council, and James Crabtree, a prominent businessman..."[11] A fifth black railroad worker was shot and killed on the street that day by a white man. Residents posted signs on roads leading into Tazewell County, warning blacks to stay away. Local communities tended to target such young, itinerant workers whose behavior they felt was outside their norms.[11]

John Peters was lynched in the town of Tazewell on April 22, 1900.[10]

Tazewell is pronounced with a short "a", to rhyme with "razz" rather than "raze".

Representation in other media

Paramount's 1994 film Lassie was filmed here. It was based on stories of Albert Payson Terhune.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 520 square miles (1,300 km2), of which 519 square miles (1,340 km2) is land and 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2) (0.2%) is water.[12]

Since it contains portions of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians and the Cumberland Plateau, Tazewell County has very distinct geologic areas within the county. One of the most unusual areas is Burke's Garden, a bowl-shaped valley formed by the erosion of a doubly plunging anticline. Tazewell County includes the headwaters of four watersheds, which are the Upper Clinch, Middle New, North Fork Holston, and Tug.[13] It also has the headwaters of the Bluestone River, which flows into West Virginia, where a portion is protected as a Wild and Scenic River.

Adjacent counties

- McDowell County, West Virginia, (North and West)

- Mercer County, West Virginia, (Northeast)

- Buchanan County, (Northwest)

- Russell County, (West)

- Smyth County, (South)

- Bland County, (East)

National protected area

- Jefferson National Forest (part)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 2,127 | — | |

| 1810 | 3,007 | 41.4% | |

| 1820 | 3,916 | 30.2% | |

| 1830 | 5,749 | 46.8% | |

| 1840 | 6,290 | 9.4% | |

| 1850 | 9,942 | 58.1% | |

| 1860 | 9,920 | −0.2% | |

| 1870 | 10,791 | 8.8% | |

| 1880 | 12,861 | 19.2% | |

| 1890 | 19,899 | 54.7% | |

| 1900 | 23,384 | 17.5% | |

| 1910 | 24,946 | 6.7% | |

| 1920 | 27,840 | 11.6% | |

| 1930 | 32,477 | 16.7% | |

| 1940 | 41,607 | 28.1% | |

| 1950 | 47,512 | 14.2% | |

| 1960 | 44,791 | −5.7% | |

| 1970 | 39,816 | −11.1% | |

| 1980 | 50,511 | 26.9% | |

| 1990 | 45,960 | −9.0% | |

| 2000 | 44,598 | −3.0% | |

| 2010 | 45,078 | 1.1% | |

| 2018 (est.) | 40,855 | [1] | −9.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] 1790-1960[15] 1900-1990[16] 1990-2000[17] 2010-2018[1] | |||

As of the census[18] of 2000, there were 44,598 people, 18,277 households and 13,232 families residing in the county. The population density was 86 people per square mile (33/km2). There were 20,390 housing units at an average density of 39 per square mile (15/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 96.16% White, 2.29% Black or African American, 0.17% Native American, 0.61% Asian, 0.16% from other races, and 0.62% from two or more races. 0.51% of the population Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 18,277 households, out of which 28.70% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.20% were married couples living together, 10.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.60% were non-families. 25.20% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 2.85.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 21.40% under the age of 18, 8.40% from 18 to 24, 27.20% from 25 to 44, 27.50% from 45 to 64, and 15.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.00 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.70 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $27,304, and the median income for a family was $33,732. Males had a median income of $28,780 versus $19,648 for females. The per capita income for the county was $15,282. About 11.70% of families and 15.30% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.30% of those under age 18 and 13.90% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Colleges

- Bluefield College, Bluefield

- Southwest Virginia Community College, borders Russell County, near Richlands

Public high schools

All public schools in Tazewell County are operated by Tazewell County Public Schools system.

Professional sports teams

- Bluefield Blue Jays, minor league baseball team based in Bluefield

Communities

Census-designated places

- Claypool Hill

- Gratton

- Raven (partially in Russell County)

- Springville

Other unincorporated communities

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 83.1% 16,731 | 15.9% 3,205 | 1.0% 198 |

| 2016 | 81.7% 15,168 | 15.6% 2,895 | 2.7% 503 |

| 2012 | 78.1% 13,843 | 20.7% 3,661 | 1.3% 228 |

| 2008 | 65.7% 11,201 | 32.8% 5,596 | 1.6% 264 |

| 2004 | 57.4% 10,039 | 41.1% 7,184 | 1.5% 257 |

| 2000 | 53.0% 8,655 | 44.2% 7,227 | 2.8% 462 |

| 1996 | 39.7% 6,131 | 48.6% 7,500 | 11.7% 1,809 |

| 1992 | 37.4% 6,375 | 50.3% 8,586 | 12.3% 2,095 |

| 1988 | 46.4% 7,165 | 52.4% 8,098 | 1.2% 190 |

| 1984 | 53.9% 9,645 | 44.8% 8,014 | 1.3% 237 |

| 1980 | 48.7% 7,021 | 48.6% 7,003 | 2.8% 401 |

| 1976 | 41.4% 5,565 | 56.3% 7,565 | 2.3% 309 |

| 1972 | 67.8% 7,233 | 29.8% 3,181 | 2.4% 253 |

| 1968 | 39.1% 4,434 | 41.8% 4,734 | 19.1% 2,170 |

| 1964 | 34.3% 3,231 | 64.6% 6,081 | 1.1% 105 |

| 1960 | 41.4% 3,139 | 58.3% 4,416 | 0.3% 19 |

| 1956 | 52.6% 3,960 | 46.4% 3,495 | 1.1% 80 |

| 1952 | 55.8% 3,232 | 43.7% 2,527 | 0.5% 30 |

| 1948 | 48.4% 2,278 | 48.0% 2,258 | 3.6% 170 |

| 1944 | 44.3% 2,271 | 55.2% 2,832 | 0.5% 25 |

| 1940 | 43.1% 2,356 | 56.8% 3,108 | 0.2% 8 |

| 1936 | 39.7% 1,981 | 59.9% 2,992 | 0.4% 22 |

| 1932 | 42.1% 2,005 | 57.0% 2,713 | 0.9% 44 |

| 1928 | 60.8% 3,072 | 39.2% 1,979 | |

| 1924 | 48.0% 2,631 | 46.9% 2,568 | 5.1% 278 |

| 1920 | 57.5% 2,408 | 42.3% 1,770 | 0.2% 9 |

| 1916 | 58.5% 1,591 | 40.7% 1,108 | 0.8% 21 |

| 1912 | 23.8% 586 | 39.8% 979 | 36.4% 897 |

See also

References

- "County Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2018". Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- GMallery, Garrick (2007). Picture-Writing of the American Indians V1. Kessinger Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 0-548-10043-8.

- Pendleton, William (1920). History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia. W. C. Hill Printing Company. p. 232.

- Pendleton, William (1920). History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia. W. C. Hill Printing Company. p. 396.

- Sterling Giles, "Shameful chapter in Virginia history: Lynchings", News-Leader, 16 May 2016; accessed 15 March 2018

- Lynching in America, 2nd edition, Supplement by County, p. 7

- Louise Leslie, Tazewell County, The Overmountain Press, 1995, pp. 149-150

- Tuskegee Institute, "Killing Grounds Lynchings Re:", Washington Post, 24 July 2005; accessed 15 March 2018

- William Fitzhugh Brundage, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930, University of Illinois Press, 1993, p. 146

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- Virginia.gov Archived 2009-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

Further reading

- Smith, J. Douglas, Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia, University of North Carolina Press, 2002

- Englund, K.J. and R.E. Thomas. (1991). Coal resources of Tazewell County, Virginia [U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1913]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

External links

- Community Foundation of the Virginias, Inc.

- Official Tazewell County website

- Tazewell County Historical Society, Tazewell, VA

- Bluefield College, Bluefield, VA

- Southwest Virginia Community College, Richlands, VA

- Historic Crab Orchard Museum & Pioneer Park, Tazewell, VA