Vietnamese folk religion

Vietnamese folk religion or Vietnamese indigenous religion (Vietnamese: tín ngưỡng dân gian Việt Nam), is the ethnic religion of the Vietnamese people. About 45.3% of the population[1] in Vietnam are associated with this religion, making it dominant in Vietnam.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Vietnam |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Literature |

| Sport |

|

Vietnamese folk religion is not an organized religious system, but a set of local worship traditions devoted to the thần, a term which can be translated as "spirits", "gods" or with the more exhaustive locution "generative powers". These gods can be nature deities or national, community or kinship tutelary deities or ancestral gods and the ancestral gods of a specific family. Ancestral gods are often deified heroic persons. Vietnamese mythology preserves narratives telling of the actions of many of the cosmic gods and cultural heroes.

The Vietnamese indigenous religion is sometimes identified as Confucianism since it carries values that were emphasized by Confucius. Đạo Mẫu is a distinct form of Vietnamese folk religion, giving prominence to some mother goddesses into its pantheon. The government of Vietnam also categorises Cao Đài as a form of Vietnamese indigenous religion, since it brings together the worship of the thần or local spirits with Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism, as well as elements of Catholicism, Spiritism and Theosophy.[2][3]

History

The Vietnamese folk religion was suppressed in different times and ways from 1945, the end of the dynastic period, to the 1980s. The destruction, neglect, or dilapidation of temples was particularly extensive in North Vietnam during the land reform (1953-1955), and in reunified Vietnam during the period of collectivisation (1975-1986).[4]

Debate and criticism of cultural destruction and loss began in the 1960s.[5] However, the period between 1975 and 1979 saw the most zealous anti-religion campaign and destruction of temples.[6] On the eve of the Đổi Mới reforms, from 1985 onwards, the state gradually returned to a policy of protection of the religious culture,[7] and the Vietnamese indigenous religion was soon promoted as the backbone of "a progressive culture, imbued with national identity".[8]

In the project of nation-building, the public discourse encourages the worship of ancient heroes of the Vietnamese identity, and gods and spirits with a long-standing presence in folk religion.[9] The relationship between the state and the local communities is flexible and dialogical in the process of religious renewal; both the state and the common people are mutual protagonists in the recent revival of Vietnamese folk religion.[10]

The concept of linh

In Vietnamese folk religion, linh (chữ Hán: 靈) has a meaning equivalent to holy and numen, that is the power of a deity to affect the world of the living.[11] Compound Sino-Vietnamese words containing the term linh indicate a large semantic field: linh-thiêng 靈聖 "sacred", linh-hiển 靈顯 "prodigious manifestation" (see xian ling), linh-ứng "responsive 靈應 (to prayers, etc.)" (see ganying), linh-nghiệm 靈驗 "efficacious", linh-hồn 靈魂 "spirit of a person", vong-linh "spirit of a dead person before 'going over'", hương-linh "spirit of a dead person that has 'gone over'".[11] These concepts derived from Chinese ling.[11] Thiêng 聖 is itself a variation of tinh, meaning "constitutive principle of a being", "essence of a thing", "daemon", "intelligence" or "perspicacity".[11]

Linh is the mediating bivalency, the "medium", between âm and dương, that is "disorder" and "order", with order (dương, yang in Chinese) preferred over disorder (âm, yin in Chinese).[12] As bivalency, linh is also metonymic of the inchoate order of creation.[13] More specifically, the linh power of an entity resides in mediation between the two levels of order and disorder which govern social transformation.[13] The mediating entity itself shifts of status and function between one level and another, and makes meaning in different contexts.[13]

This attribute is often associated with goddesses, animal motifs such as the snake—an amphibian animal—, the owl which takes night for day, the bat being half bird and half mammal, the rooster who crows at the crack between night and morning, but also rivers dividing landmasses, and other "liminal" entities.[13] There are âm gods such as Nguyễn Bá Linh, and dương gods such as Trần Hưng Đạo.[14] Linh is a "cultural logic of symbolic relations", that mediates polarity in a dialectic governing reproduction and change.[15]

Linh has also been described as the ability to set up spatial and temporal boundaries, represent and identify metaphors, setting apart and linking together differences.[16] The boundary is crossed by practices such as sacrifice and inspiration (shamanism).[16] Spiritual mediumship makes the individual the center of actualising possibilities, acts and events indicative of the will of the gods.[16] The association of linh with liminality implies the possibility of constructing various kinds of social times and history.[17] In this way, the etho-political (ethnic) dimension is nurtured, regenerated by re-enactment, and constructed at first place, imagined and motivated in the process of forging a model of reality.[17]

Confucianism and Taoism

_(4356115370).jpg.webp)

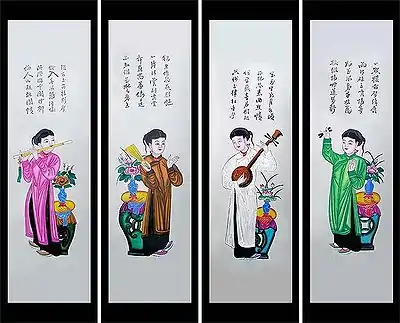

The Vietnamese folk religion fosters Confucian values, and it is for this reason often identified as "Confucianism". Temples of Literature (Văn Miếu) are temples devoted to the worship of Confucius that in imperial times also functioned as academies.

Taoism is believed to have been introduced into Vietnam during the first Chinese domination of Vietnam. In its pure form it is rarely practiced in Vietnam, but can still be seen in places with Chinese communities such as Saigon, where there is a community of Cantonese/Vietnamese Taoist priest residing in the Khánh Vân Nam Viện Pagoda. Elements of its doctrines have also been absorbed into the Vietnamese folk religion.[18] Taoist influence is also recognisable in the Caodaist and Đạo Mẫu[19] religions.

According to Professor Liam Keelley during the Tang dynasty native spirits were subsumed into Daoism and the Daoist view of these spirits completely replaced the original native tales.[20] Buddhism and Daoist replaced native narratives surrounding Mount Yên Tử 安子山.[21]

Indigenious religious movements

Caodaism

The Cao Đài faith (Vietnamese: Đạo Cao Đài "Way of the Highest Power") is an organised monotheistic Vietnamese folk religion formally established in the city of Tây Ninh in southern Vietnam in 1926.[22][2]The full name of the religion is Đại Đạo Tam Kỳ Phổ Độ ("Great Way [of the] Third Time [of] Redemption").[22] Followers also call their religion Đạo Trời ("Way of God"). Cao Đài has common roots and similarities with the Tiên Thiên Đạo doctrines.[23]

Cao Đài (Vietnamese: [kāːw ɗâːj] (![]() listen), literally the "Highest Lord" or "Highest Power")[22] is the highest deity, the same as the Jade Emperor, who created the universe.[24] He is worshipped in the main temple, but Caodaists also worship the Mother Goddess, also known as the Queen Mother of the West (Diêu Trì Kim Mẫu, Tây Vương Mẫu). The symbol of the faith is the Left Eye of God, representing the dương (masculine, ordaining, positive and expansive) activity of the male creator, which is balanced by the yin (âm) activity of the feminine, nurturing and restorative mother of humanity.[2][22]

listen), literally the "Highest Lord" or "Highest Power")[22] is the highest deity, the same as the Jade Emperor, who created the universe.[24] He is worshipped in the main temple, but Caodaists also worship the Mother Goddess, also known as the Queen Mother of the West (Diêu Trì Kim Mẫu, Tây Vương Mẫu). The symbol of the faith is the Left Eye of God, representing the dương (masculine, ordaining, positive and expansive) activity of the male creator, which is balanced by the yin (âm) activity of the feminine, nurturing and restorative mother of humanity.[2][22]

Đạo Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương

Đạo Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương ("Way of the Strange Fragrance from the Precious Mountain") is a religious tradition with Buddhist,Taoist,Confusianism,Zen,Yiguandao elements, originally practiced by the mystic Đoàn Minh Huyên (1807–1856) and continued by Huỳnh Phú Sổ, founder of the Hòa Hảo sect. The name itself refers to the Thất Sơn range on the Vietnamese-Cambodian border, where Huyên claimed to be a living Buddha,Vietnamese folk religion,Zen,Yiguandao.

During a cholera epidemic in 1849, which killed over a million people, Huyên was reputed to have supernatural abilities to cure the sick and the insane. His followers wore amulets bearing the Chinese characters for Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương, a phrase that became identified, retrospectively, with the religion practiced by Huyên, and the millenarian movement associated with the latter. The faith has roughly 15,000 adherents mostly concentrated in the provinces of An Giang, Đồng Tháp, Bà Rịa-Vũng Tàu, Long An, Sóc Trăng, Vĩnh Long, Tiền Giang and Bến Tre.

Đạo Mẫu

Đạo Mẫu ("Way of the Mother") refers to the worship of the Mẫu (the Mother Goddess) and the various mother goddesses, constituting a central feature of Vietnamese folk religion.[25] The worship of female goddesses by the Vietnamese dates back to prehistory.[25] It is possible that the concept of a Mother Goddess came to encompass the different spirits of nature as one only spirit manifesting itself in a variety of forms.[25] Along history, various human heroines, emerged as protectors or healers, were deified as other manifestations of the Mother Goddess.[25]

As a distinct movement with its own priesthood (made of shamans capable of merging the material and the spiritual world), temples, and rituals, Đạo Mẫu was revived since the 1970s in North Vietnam and then in the newly unified country.[26] In the pantheon of Đạo Mẫu the Jade Emperor (Ngọc Hoàng) is viewed as the supreme, originating god,[27] but he is regarded as abstract and rarely worshipped.[28] The supreme goddess is Thánh Mẫu Liễu Hạnh.[29] The pantheon of the religion includes many other gods, both male and female.[30]

Đạo Tứ Ân Hiếu Nghĩa

Đạo Tứ Ân Hiếu Nghĩa or just Đạo Hiếu Nghĩa is an organised Vietnamese folk religion founded in the late 1800s. It has roughly 80,000 followers scattered throughout southern Vietnam, but especially concentrated in Tri Tôn District.[31]

Minh Đạo

The Minh Đạo or Đạo Minh is a group of five religions that have Tiên Thiên Đạo roots in common with, yet pre-date and have influenced, Caodaism.[32] Minh Đạo means the "Way of Light". They are part of the broad milieu of Chinese-Vietnamese religious sectarianism.[33] After the 17th century, when the Ming dynasty saw its power decline, a large number of Minh sects started to emerge in Cochinchina, especially around Saigon.[33]

The Chinese authorities took little interest in these sects, since, at least until the early 20th century, they limited their activities to their temples.[33] They were autonomous structures, focusing on worship, philanthropy and literature.[33] Yet they had embryonic Vietnamese nationalistic elements, which evolved along the development of their political activity in the early 20th century.[33]

Five Minh Đạo movements appeared in southern Vietnam in the 19th and 20th centuries: Minh Sư Đạo ("Way of the Enlightened Master"), Minh Lý Đạo ("Way of the Enlightened Reason"), Minh Đường Đạo ("Way of the Temple of Light"), Minh Thiện Đạo ("Way of the Foreseeable Kindness") and Minh Tân Đạo ("Way of the New Light").[33]

The founder of Minh Lý Đạo was Âu Kiệt Lâm (1896–1941), an intellectual of half Chinese and half Vietnamese blood, and a shaman, capable of transcending the cultural barriers of the two peoples.[34] The primary deities of the pantheon of the sects are the Jade Emperor (Ngọc Hoàng Thượng Đế) and the Queen Mother of the West (Tây Vương Mẫu).[34]

Symbolic, liturgical and theological features of the Minh Đạo sects were shared with the Caodaist religion.[35] From 1975 onwards, the activities and temples of some of the Minh Đạo religions have been absorbed into sects of Caodaism, while others, especially Minh Đường Đạo and Minh Lý Đạo, have remained distinct.[36]

Minh Đường Trung Tân

The Minh Đường Trung Tân ("School of Teaching Goodness") emerged in the 1990s in the Vĩnh Bảo District, a rural area of the city of Hải Phòng. A local carpenter known simply as "Master Thu" claimed to have been visited at night by the spirit of 16th-century sage Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm, who ordered him to build a shrine in his honor. Thu owned some land, where he built and inaugurated in 1996 a shrine to Khiêm. By 2016, it had attracted more than 10,000 visitors, and Thu had organized around the channeled messages of Khiêm a new religious movement with thousands of followers.[37]

Features

Deities

A rough typological identification of Vietnamese gods categorises them into four categories:[38]

- Heavenly gods (thiên thần) and nature gods (nhiên thần) of grottoes, rocks and trees, rivers and oceans, rain and lightning, generative or regenerative powers of the cosmos or a locality, with geo-physical or anthropomorphic representations (sometimes using iconographic styles of Buddhist derivation).

- Tutelary gods or deified ancestors or progenitors (nhân thần), originally either consecrated by villagers or installed by the Vietnamese or Chinese rulers. They include heroes, founding patriarchs, able men and founders of arts and crafts. This category can include impure spirits (dâm thần).

- Various hierarchical or court-like pantheons inherited from the Taoist patterns, headed by the Heavenly Emperors, the immortals (tiên), the holy sages (thánh), including the local "divine ensembles" (chư vị). They are mostly Vietnamese formations, but often with sinicised motifs.

- Deities of Cham, Khmer, and other Southeast Asian ethnic origin, such as Po Yan Inu Nagar (Thiên Y A Na), Ca Ong the whale god, and the rocks Neak Ta (Ong Ta).

Some of the most popular gods are: Kinh Dương Vương and his son Lạc Long Quân—who, with his wife Âu Cơ, gave rise to the Vietnamese race—, The Four Immortals (Tản Viên Sơn Thánh, Thánh Gióng, Chử Đồng Tử, and Liễu Hạnh), the Four Palaces' goddesses (Mẫu Thượng Thiên, Mẫu Thượng Ngàn, Mẫu Thoải, and Mẫu Địa Phủ), Trần Hưng Đạo, Sơn Tinh and Thủy Tinh, Bà Chúa Kho, Bà Chúa Xứ, Thần Nông, Bà Đen, Quán Thế Âm, the bà mụ, and others. The Vietnamese mythology is the body of holy narrative telling the actions of many of these gods.

Forms of worship and practices

The linh of the gods, as it is appropriated for social construction, is also appropriated in self-cultivation.[17] It provides a locus for dialectical relations, between the individual and his or her social others, and between the self and the spirits, to intersect and overlap.[39] This is especially true of the experiences provided through shamanic practices such as lên đồng.[17]

Within the field of self-cultivation, action of self-empowering is expressed in a cluster of Vietnamese terms: tu "to correct", "to improve", as in tu thân "self-perfecting with meditation", tu hiền "to cultivate gentleness/wisdom", or tu sứa "to correct", "to repair"; the word chữa "to repair", "to correct", as in sứa chữa "correction", "repair", or chữa trị "to cure an illness"; the word cứu "to rescue", as in cứu chữa "to cure", "to heal", in cứu rỗi "to save souls", and cứu nước "to save the country".[39]

The practice of self-cultivation knits together the individual and the social in an orientation of discourse and action.[39] The individual project gives rise to a matrix of potentials, with which the individual deals with personal crises by constructing new meanings, seen as modalities of perfectibility.[40]

Places of worship

Vietnamese temples are generically called miếu (meaning "temple") in Vietnamese language. In the northern regions, the miếu are temples hosting the "main worship" of a deity and usually located at secluded places,[41] while đình, đền, điện, đài or tịnh are temples for "emissary" or "secondary worship" located nearer or within habitation places.[41] In southern regions the two categories tend to blur.[41] Nhà thờ họ are family shrines of northern and middle Vietnam, equivalent to the Chinese ancestral shrines.

Another categorisation proposed by observing the vernacular usage is that miếu are temples enshrining nature gods (earth gods, water gods, fire gods), or family chapels (gia miếu); đình are shrines of tutelary deities of a place; and đền are shrines of deified heroes, kings, and other virtuous historical persons.[41] Actually, other terms, often of local usage, exist.[41] For example, in middle Vietnam one of the terms used is cảnh, and in Quảng Nam Province and Quảng Ngãi Province a native term is khom.

Phủ ("palace") refers to a templar complex of multiple buildings, while one single building is a đền.[25] In English, in order to avoid confusion with Vietnamese Buddhist temples, đền and other words for of the Vietnamese folk religion's temples are commonly translated as "shrine".

See also

References

- Vietnamese folk religion#cite note-FOOTNOTEPew Research Center2012-1

- Hoskins 2015.

- Hoskins (a) 2012.

- Roszko 2012, p. 28.

- Roszko 2012, pp. 28-30.

- Roszko 2012, p. 30.

- Roszko 2012, p. 31.

- Roszko 2012, p. 33.

- Roszko 2012, p. 35.

- Roszko 2012, pp. 35-36.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 9.

- Đõ̂ 2003, pp. 10-11.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 11.

- Đõ̂ 2003, pp. 12-13.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 13.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 14.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 15.

- Bryan S. Turner; Oscar Salemink (25 September 2014). Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia. Routledge. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-1-317-63646-5.

- Vu 2006, p. 30.

- "The Daoist Appropriation/Subordination of Bấch Hấc Spirits – Le Minh Khai's SEAsian History Blog". Leminhkhai.wordpress.com. 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- "Elephant Mountain and the Erasure of Việt Indigeneity – Le Minh Khai's SEAsian History Blog". Leminhkhai.wordpress.com. 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2016-10-15.

- Hoskins (b) 2012, p. 3.

- Goossaert & Palmer 2011, pp. 100-102.

- Oliver 1976.

- Vu 2006, p. 27.

- Vu 2006, pp. 28-30.

- Vu 2006, p. 31.

- Vu 2006, p. 33.

- Vu 2006, p. 32.

- Vu 2006, pp. 33-34.

- ĐÔI NÉT VỀ ĐẠO TỨ ÂN HIẾU NGHĨA. gov.vn

- Jammes 2010, p. 357.

- Jammes 2010, p. 358.

- Jammes 2010, p. 359.

- Jammes 2010, p. 360.

- Jammes 2010, pp. 364-365.

- Hoang 2017, pp. 59-85.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 3.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 16.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 18.

- Đõ̂ 2003, p. 21.

Sources

- Roszko, Edyta (2012), "From Spiritual Homes to National Shrines: Religious Traditions and Nation-Building in Vietnam" (PDF), East Asia, 29: 25–41, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.467.6835, doi:10.1007/s12140-011-9156-x, S2CID 52084986

- Hoskins (b), Janet Alison (2012), "God's Chosen People": Race, Religion and Anti-Colonial Struggle in French Indochina, Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore

- Hoskins (a), Janet Alison (2012), What Are Vietnam's Indigenous Religions? (PDF), Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

- Hoskins, Janet Alison (2015), The Divine Eye and the Diaspora: Vietnamese Syncretism Becomes Transpacific Caodaism, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-824-85140-8

- Jammes, Jerémy (2010), "Divination and Politics in Southern Vietnam: Roots of Caodaism" (PDF), Social Compass, 57 (3): 357–371, doi:10.1177/0037768610375520, S2CID 144754326

- Pew Research Center (2012), Pew Forum: The Global Religious Landscape 2010 - Indigenous religions, retrieved March 18, 2015

- Đõ̂, Thiện (2003), Vietnamese Supernaturalism: Views from the southern region, Psychology Press, ISBN 9780415307994

- Vu, Tu Anh T (2006), "Worshipping the Mother Goddess. The Dao Mao movement in Northern Vietnam" (PDF), Explorations in Southeast Asian Studies, 6 (1): 27–44

- Goossaert, Vincent; Palmer, David A. (2011), The Religious Question in Modern China, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226304168

- Oliver, Victor L. (1976), Caodai Spiritism: A Study of Religion in Vietnamese Society, BRILL, ISBN 9789004045477

- Hoang, Chung Van (2017), New Religions and State's Response to Religious Diversification in Contemporary Vietnam: Tensions from the Reinvention of the Sacred, Springer, ISBN 9783319584997