1948 Palestinian exodus from Lydda and Ramle

The 1948 Palestinian exodus from Lydda and Ramle, also known as the Lydda Death March,[1][2] was the expulsion of 50,000–70,000[3] Palestinian Arabs when Israeli troops captured the towns in July that year. The military action occurred within the context of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The two Arab towns, lying outside the area designated for a Jewish state in the UN Partition Plan of 1947, and inside the area set aside for an Arab state in Palestine,[4][5] subsequently were transformed into predominantly Jewish areas in the new State of Israel, known as Lod and Ramla.[6]

Refugees leaving Ramle | |

| Date | July 1948 |

|---|---|

| Location | Lydda, Ramle, and surrounding villages, then part of Mandatory Palestine, now part of Israel |

| Also known as | Lydda Death March[1][2] |

| Participants | Israel Defense Forces, Arab Legion, Arab residents of Lydda and Ramle |

| Outcome | 50,000–70,000 residents fled from, or were expelled by, the IDF |

The exodus, constituting 'the biggest expulsion of the war',[7] took place at the end of a truce period, when fighting resumed, prompting Israel to try to improve its control over the Jerusalem road and its coastal route which were under pressure from the Jordanian Arab Legion, Egyptian and Palestinian forces. From the Israeli perspective, the conquest of the towns, designed, according to Benny Morris, 'to induce civilian panic and flight,'[8] averted an Arab threat to Tel Aviv, thwarted an Arab Legion advance by clogging the roads with refugees, forcing the Arab Legion to assume a logistical burden that would undermine its military capacities, and helped demoralise nearby Arab cities.[9][10] On 10 July, Glubb Pasha ordered the defending Arab Legion troops to "make arrangements ... for a phony war".[11] The next day, Ramle surrendered immediately, but the conquest of Lydda took longer and led to an unknown number of deaths; the Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref, the only scholar who tried to draw up a balance sheet for the Palestinian losses, estimated 426 Palestinians died in Lydda on 12 July, of which 176 in the mosque and 800 overall in the fighting.[12] Israeli historian Benny Morris suggests up to 450 Palestinians and 9–10 Israeli soldiers died.[13]

Once the Israelis were in control of the towns, an expulsion order signed by Yitzhak Rabin was issued to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) stating, "1. The inhabitants of Lydda must be expelled quickly without attention to age....".[14] Ramle's residents were bussed out, while the people of Lydda were forced to walk miles during a summer heat wave to the Arab front lines, where the Arab Legion, Transjordan's British-led army, tried to provide shelter and supplies.[15] A number of the refugees died during the exodus from exhaustion and dehydration, with estimates ranging from a handful to a figure of 500.[16]

The events in Lydda and Ramle accounted for one-tenth of the overall Arab exodus from Palestine, known in the Arab world as al-Nakba ("the catastrophe"). Some scholars, including Ilan Pappé, have characterised what occurred at Lydda and Ramle as ethnic cleansing.[17] Many Jews who came to Israel between 1948 and 1951 settled in the refugees' empty homes, both because of a housing shortage and as a matter of policy to prevent former residents from reclaiming them.[18] Ari Shavit noted that the "events were crucial phase of the Zionist revolution, and they laid the foundation for the Jewish state."[19]

Background

1948 Palestine War

Palestine was under the rule of the British Mandate from 1917 to 1948. After 30 years of intercommunal conflict between Jewish and Arab Palestinians, on 29 November 1947, the United Nations voted to partition the territory into a Jewish and an Arab state, with Lydda and Ramle to form part of the latter.

The proposal was welcomed by Palestine's Jewish community but rejected by the Arab leaders and civil war broke out between the communities. British authority broke down as the civil war spread, taking care only of little more than the evacuation of their own forces, although they maintained an air and sea blockade. After the first 4.5 months of fights, the Jewish militias had defeated the Arab ones and conquered the main mixed cities of the country, triggering the 1948 exodus of Palestinian Arabs. During that period between 300,000 and 350,000 Arab Palestinians fled or were expelled from their lands.

The British Mandate expired on 14 May 1948, and the State of Israel declared its independence.[20] Transjordan, Egypt, Syria and Iraq intervened by sending expeditionary forces that entered former Mandatory Palestine and engaged Israeli forces. Six weeks of fighting followed, after which none of the belligerents had won the upper hand.

After four weeks of truce, during which Israeli forces reinforced whereas Arab ones suffered under the embargo, the fighting resumed. The Lydda and Ramle events took place during that period.

Strategic importance of Lydda and Ramle

Lydda (Arabic: Al-Ludd اَلْلُدّْ) dates back to at least 5600–5250 BCE. Ramle (ar-Ramlah الرملة), three kilometers away, was founded in the 8th century CE. Both towns were strategically important because they sat at the intersection of Palestine's main north–south and east–west roads. Palestine's main railway junction and its airport (now Ben Gurion International Airport) were in Lydda, and the main source of Jerusalem's water supply was 15 kilometers away.[21] Jewish and Arab fighters had been attacking each other on roads near the towns since hostilities broke out in December 1947. Israeli geographer Arnon Golan writes that Palestinian Arabs had blocked Jewish transport to Jerusalem at Ramle, causing Jewish transportation to shift to a southern route. Israel had launched several ground or air attacks on Ramle and Latrun in May 1948, and Israel's prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, developed what Benny Morris calls an obsession with the towns; he wrote in his diary that they had to be destroyed, and on 16 June referred to them during an Israeli cabinet meeting as the "two thorns".[22] Lydda's local Arab authority, officially subordinated to the Arab Higher Committee, assumed local civic and military powers. The records of Lydda's military command discuss military training, constructing obstacles and trenches, requisitioning vehicles and assembling armoured cars armed with machine-guns, and attempts at arms procurement. In April 1948, Lydda had become an arms supply center, and provided military training and security coordination for the neighboring villagers.[9]

Operation Dani

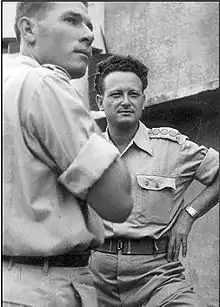

Israel subsequently launched Operation Danny to secure the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem road and neutralise any threat to Tel Aviv from the Arab Legion, which was stationed in Ramallah and Latrun, with a number of men in Lydda.[23] On 7 July the IDF appointed Yigal Allon to head the operation, and Yitzhak Rabin, who became Israel's prime minister in 1974, as his operations officer; both had served in the Palmach, an elite fighting force of the pre-Israel Jewish community in Palestine. The operation was carried out between 9 July 1948, the end of the first truce in the Arab-Israeli war, and 18 July, the start of the second truce, a period known in Israeli historiography as the Ten Days. Morris writes that the IDF assembled its largest force ever: the Yiftach brigade; the Eighth Armoured Brigade's 82nd and 89th Battalions; three battalions of Kiryati and Alexandroni infantry men; an estimated 6,000 men with around 30 artillery pieces.[24][25]

Lydda's defenses

In July 1948 Lydda and Ramle had a joint population of 50,000–70,000 Palestinian Arabs, 20,000 of them refugees from Jaffa and elsewhere.[26] Several Palestinian Arab towns had already fallen to Jewish or Israeli advances since April, but Lydda and Ramle had held out. There are differing views as to how well-defended the towns were. In January 1948, John Bagot Glubb, the British commander of Transjordan's Arab Legion, had toured Palestinian Arab towns, including Lydda and Ramle, urging them to prepare to defend themselves. The Legion had distributed barbed wire and as many weapons as could be spared.[27] Lydda had an outer line of defense and prepared positions, an antitank ditch and field artillery as well as a heavily fortified and armed line northeast of central Lydda.[9]

Israeli historians Alon Kadish and Avraham Sela write that the Arab National Committee—a local emergency Arab authority that answered to the Arab Higher Committee run by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem—had assumed civic and military control of Lydda, and had acquired arms, conducted training, constructed trenches, requisitioned vehicles, and organised medical services. By the time of the Israeli attack, they say the militia in Lydda numbered 1,000 men equipped with rifles, submachine guns, 15 machine guns, five heavy machine guns, 25 anti-tank launchers, six or seven light field-guns, two or three heavy ones, and armoured cars with machine guns. The IDF estimated that there was an Arab Legion force of around 200-300 men. Lydda contained several hundred Bedouin volunteers and a large-sized force of the Arab Legion. They argue that the deaths in Lydda occurred during a military battle for the town, not because of a massacre.[28]

Against this view, Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi writes that just 125 Legionnaires from the Fifth Infantry Company were in Lydda—the Arab Legion numbered 6,000 in all—and that the rest of the town's defense consisted of civilian residents acting under the command of a retired Arab Legion sergeant.[29] According to Morris, a number of Arab Legion soldiers, including 200–300 Bedouin volunteers, had arrived in Lydda and Ramle in April, and a company-sized force had set itself up in the old British police stations in Lydda and on the Lydda-Ramle road, with armoured cars and other weapons. He writes that there were 150 Legionnaires in the town in June, though the Israelis believed there were up to 1,500. An Arab Legion officer was appointed military governor of both towns, signaling the desire of Abdullah I of Jordan to stake a claim in the parts of Palestine allotted by the UN to a Palestinian Arab state, but Glubb advised him that the Legion was overstretched and could not hold the towns. As a result, Abdullah ordered the Legion to assume a defensive position only, and most of the Legionnaires in Lydda withdrew during the night of 11–12 July.[30]

Kadish and Sela write that the National Committee stopped women and children from leaving, because their departure had acted elsewhere as a catalyst for the men to leave too. They say it was common for Palestinian Arabs to leave their homes under threat of Israeli invasion, in part because they feared atrocities, particularly rape, and in part because of a reluctance to live under Jewish rule. In Lydda's case, they argue, the fears were more particular: a few days before the city fell, a Jew found in Lydda's train station had been publicly executed and his body mutilated by residents, who, according to Kadish and Sela, now feared Jewish reprisals.[28]

Fall of the cities

Air attacks and surrender of Ramle

The Israeli air force began bombing the towns on the night of 9–10 July, intending to induce civilian flight, and it seemed to work in Ramle: at 11:30 hours on 10 July, Operation Dani headquarters (Dani HQ) told the IDF that there was a "general and serious flight from Ramla." That afternoon, Dani HQ told one of its brigades to facilitate the flight from Ramle of women, children, and the elderly, but to detain men of military age.[26] On the same day, the IDF took control of Lydda airport.[31] The Israeli air force dropped leaflets over both towns on 11 July telling residents to surrender.[32] Ramle's community leaders, along with three prominent Arab family representatives, agreed to surrender, after which the Israelis mortared the city and imposed a curfew. The New York Times reported at the time that the capture of the city was seen as the high point of Israel's brief existence.[33]

Two different images emerged of Ramle under occupation. Khalil Wazir, who later joined the PLO and became known as Abu Jihad, was evicted from the town with his family, who owned a grocer's store there, when he was 12 years old. He said there was fear of a massacre, as there had been at Deir Yassin, and that there were bodies scattered in the streets and between the houses, including the bodies of women and children.[34] Against this, the writer Arthur Koestler (1905–1983), working for The Times, visited Ramle a few hours after the invasion, and said people were hanging around in the streets as usual. A few hundred young men had been placed in a barbed wire cage, and were being taken in lorries to an internment camp. Women were bringing them food and water, he wrote, arguing with the Jewish guards and seemingly unafraid. He said the prevailing feeling seemed to be relief that the war was over.[35]

Moshe Dayan raid on Lydda

During the afternoon of 11 July, Israel's 89th (armoured) Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Moshe Dayan, moved into Lydda. Israeli historian Anita Shapira writes that the raid was carried out on Dayan's initiative without coordinating it with his commander. Using a column of jeeps led by a Marmon-Herrington Armoured Car with a cannon—taken from the Arab Legion the day before—he launched the attack in daylight,[37] driving through the town from east to west machine-gunning anything that moved, according to Morris, then along the Lydda-Ramle road firing at militia posts until they reached the train station in Ramle.[38] Kadish and Sela write that the troops faced heavy fire from the Arab Legion in the police stations in Lydda and on the Lydda-Ramle road and Dayan described "The town's [southern] entrance was awash with Arab combatants ... Hand grenades were thrown from all directions. There was a tremendous confusion."[28] A contemporaneous account from Gene Currivan for The New York Times also said the firing met with heavy resistance. Dayan's men advanced until the train station where the wounded were treated, and returned to Bet Shemen under continued enemy fire from the police stations. Six of his men were killed and 21 were wounded.[9][39]

Kenneth Bilby, a correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, was in the city at the time. He wrote: "[The Israeli jeep column] raced into Lydda with rifles, Stens, and sub-machine guns blazing. It coursed through the main streets, blasting at everything that moved ... the corpses of Arab men, women, and even children were strewn about the streets in the wake of this ruthlessly brilliant charge."[36] The raid lasted 47 minutes, leaving 100–150 Palestinian Arabs dead, according to Dayan's 89th Battalion. The Israeli side lost 6 dead and 21 wounded.[40] Kadish and Sela write that the high casualty rate was caused by confusion over who Dayan's troops were. The IDF were wearing keffiyehs and were led by an armoured car seized from the Arab Legion. Residents may have believed the Arab Legion had arrived, only to encounter Dayan's forces shooting at everything as they ran from their homes.[28]

Surrender and unexpected shooting in Lydda by Arab Legionnaires

Although no formal surrender was announced in Lydda, people gathered in the streets waving white flags. On the evening of 11 July, 300–400 Israeli soldiers entered the town. Not long afterwards, the Arab Legion forces on the Lydda–Ramle road withdrew, though a small number of Legionnaires remained in the Lydda police station. More Israeli troops arrived at dawn on 12 July. According to a contemporaneous IDF account: "Groups of old and young, women and children streamed down the streets in a great display of submissiveness, bearing white flags, and entered of their own free will the detention compounds we arranged in the mosque and church—Muslims and Christians separately." The buildings soon filled up, and women and children were released, leaving several thousand men inside, including 4,000 in one of the mosque compounds.[41]

The Israeli government set up a committee to handle the Palestinian Arab refugees and their abandoned property. The committee issued an explicit order that forbade "to destroy, burn or demolish Arab towns and villages, to expel the inhabitants of Arab villages, neighbourhoods and towns, or to uproot the Arab population from their place of residence" without having previously received, a specific and direct order from the Minister of Defense. Regulations ordered the sealing off of Arab areas to prevent looting and acts of revenge and stated that captured men were to be treated as POWs with the Red Cross notified. Palestinian Arabs who wished to remain were allowed to do so and the confiscation of their property was prohibited.[9]

The town dignitaries were assembled and after discussion, decided to surrender. Lydda's inhabitants were instructed to leave their weapons on the doorsteps to be collected by soldiers but did not do so. A curfew for that evening was announced over loudspeakers. A delegation of town dignitaries, including Lydda's mayor, left for the police station to prevail upon the Legionnaires there to also surrender. They refused and fired upon the party, killing the mayor and wounding several others. Despite this, the Israeli 3rd Battalion decided to accept the town's surrender. Israeli historian Yoav Gelber writes that the Legionnaires still in the police station were panicking, and had been sending frantic messages to their HQ in Ramallah: "Have you no God in your hearts? Don't you feel any compassion? Hasten aid!"[31] They were about to surrender, but were told by their HQ to wait to be rescued.[9][42]

On 12 July, at 11:30 hours, two or three Arab Legion armoured cars entered the city, led by Lt. Hamadallah al-Abdullah from the Jordanian 1st Brigade. The Arab Legion armoured cars opened fire on the Israeli soldiers combing the Old City, which created the impression that the Jordanians had staged a counterattack. The exchange of gunfire led residents and Arab fighters to believe the Legion had arrived in force, and those still armed started firing at the Israelis too. Local militia renewed hostilities and an Israeli patrol were set upon by a rioting mob in the market place. The Israeli military sustained many casualties, and viewing the renewed resistance as a surrender agreement violation, quickly quelled it, and many civilians died.[9][43] Kadish and Sela write that, according to the 3rd Battalion's commander, Moshe Kelman, the Israelis came under heavy fire from "thousands of weapons from every house, roof and window". Morris calls this "nonsense" and argues that only a few dozen townspeople took part in what turned out to be a brief firefight.[44]

Massacre in Lydda

Gelber describes what followed as probably the bloodiest massacre of the Arab–Israeli war. Shapira writes that the Israelis had no experience of governing civilians and panicked.[45] Kelman ordered troops to shoot at any clear target, including at anyone seen on the streets.[46] He said he had no choice; there was no chance of immediate reinforcements, and no way to determine the enemy's main thrust.[28] Israeli soldiers threw grenades into houses they suspected snipers were hiding in. Residents ran out of their homes in panic and were shot. Yeruham Cohen, an IDF intelligence officer, said around 250 died between 11:30 and 14:00 hours.[47]

However, Kadish and Sela state that there is no direct first-hand evidence that a massacre took place, other than a few dubious Arab sources. They say that a reconstruction of the battle suggests a "better, albeit more complex, explanation of the Arab losses" which also "casts severe doubt on, if it does not completely refute, the argument for the massacre in the al-'Umari Mosque."[9] This view has been criticised. Quoting from Kadish and Sela's paper, John W. Pool concluded: "«... on the morning of 12 July 1948, 'The Palmach forces in (Lydda) came under heavy fire from 'thousands of weapons from every house, roof and window' sustaining heavy casualties.» These assertions seem to be the foundation for much of the argument advanced in the article. I think that the authors should have furnished much more information about their precise meaning, factual validity, and sources." He continues: "he (Benny Morris) does not say how many townspeople were involved in the fighting but his account certainly suggests a number of Arab gunmen very much smaller than several thousand" (noted by Kadish and Sela).[48] James Bowen is also critical. He places a cautionary note on the UCC web site: "... it is based on a book written by the same authors which was published in 2000 by the Israeli Ministry of Defence."[49]

Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref placed the death toll at 426, including 179 he said were later killed in one of the mosques, during a confusing incident that sources variously refer to as a massacre or a battle.[50] Thousands of male Muslim detainees had been taken to two of the mosques the day before. Christian detainees had been taken to the church or a nearby Greek Orthodox monastery, leaving the Muslims in fear of a massacre.[51] Morris writes that some of them tried to break out, thinking they were about to be killed, and in response the IDF threw grenades and fired anti-tank rockets into one of the mosque compounds. Kadish and Sela say it was a firefight that broke out between armed militiamen inside the mosque and Israeli soldiers outside and responding to attacks originating from the mosque, the Israelis fired an anti-tank shell into it, then stormed it, killing 30 militiamen inside.[9] In 2013, in testimony provided to Zochrot, Yerachmiel Kahanovich, a Palmach fighter present on the scene, stated he himself, amid the shelling of a mosque, had fired a PIAT anti-tank missile with enormous shock wave impact inside the mosque, and on examining it afterwards found the walls scattered with the remains of people. He also stated that anyone straying from the flight trail was shot dead.[52] According to Morris, dozens died, including unarmed men, women and children; an eyewitness published a memoir in 1998 saying he had removed 95 bodies from one of the mosques.[53]

When the shooting was over, bodies lay in the streets and houses in Lydda, and on the Lydda–Ramle road; Morris writes that there were hundreds. The Red Cross was due to visit the area, but the new Israeli military governor of Ramle issued an order to have the visit delayed. The visit was rescheduled for 14 July; Dani HQ ordered Israeli troops to remove the bodies by then, but the order seems not to have been carried out. Dr. Klaus Dreyer of the IDF Medical Corps complained on 15 July that there were still corpses lying in and around Lydda, which constituted a health hazard and a "moral and aesthetic issue." He asked that trucks and Arab residents be organized to deal with them.[54]

Exodus

Expulsion orders

Benny Morris writes that David Ben-Gurion and the IDF were largely left to their own devices to decide how Palestinian Arab residents were to be treated, without the involvement of the Cabinet and other ministers. As a result, their policy was haphazard and circumstantial, depending in part on the location, but also on the religion and ethnicity of the town. The Palestinian Arabs of Western and Lower Galilee, mainly Christian and Druze, were allowed to stay in place, but Lydda and Ramle, mainly Muslim, were almost completely emptied.[55] There was no official policy to expel the Palestinian population, he writes, but the idea of transfer was "in the air", and the leadership understood this.[56]

_cropped.jpg.webp)

As the shooting in Lydda continued, a meeting was held on 12 July at Operation Dani headquarters between Ben-Gurion, Yigael Yadin and Zvi Ayalon, generals in the IDF, and Yisrael Galili, formerly of the Haganah, the pre-IDF army. Also present were Yigal Allon, commanding officer of Operation Dani, and Yitzhak Rabin.[58] At one point Ben-Gurion, Allon, and Rabin left the room. Rabin has offered two accounts of what happened next. In a 1977 interview with Michael Bar-Zohar, Rabin said Allon asked what was to be done with the residents; in response, Ben-Gurion had waved his hand and said, "garesh otam"—"expel them."[59] In the manuscript of his memoirs in 1979, Rabin wrote that Ben-Gurion had not spoken, but had only waved his hand, and that Rabin had understood this to mean "drive them out."[58] The expulsion order for Lydda was issued at 13:30 hours on 12 July, signed by Rabin.[60]

In his memoirs Rabin wrote: "'Driving out' is a term with a harsh ring. Psychologically, this was one of the most difficult actions we undertook. The population of Lod did not leave willingly. There was no way of avoiding the use of force and warning shots in order to make the inhabitants march the 10 to 15 miles to the point where they met up with the legion." An Israeli censorship board removed this section from his manuscript, but Peretz Kidron, the Israeli journalist who translated the memoirs into English, passed the censored text to David Shipler of The New York Times, who published it on 23 October 1979.[58]

In an interview with The New York Times two days later, Yigal Allon took issue with Rabin's version of events. "With all my high esteem for Rabin during the war of independence, I was his commander and my knowledge of the facts is therefore more accurate," he told Shipler. "I did not ask the late Ben-Gurion for permission to expel the population of Lydda. I did not receive such permission and did not give such orders." He said the residents left in part because they were told to by the Arab Legion, so the latter could recapture Lydda at a later date, and in part because they were panic-stricken.[61] Yoav Gelber also takes issue with Rabin's account. He writes that Ben-Gurion was in the habit of expressing his orders clearly, whether verbally or in writing, and would not have issued an order by waving his hand; he adds that there is no record of any meetings before the invasion that indicate expulsion was discussed. He attributes the expulsions to Allon, who he says was known for his scorched earth policy. Wherever Allon was in charge of Israeli troops, Gelber writes, no Palestinians remained.[62] Whereas traditional historiography in Israel has insisted that Palestinian refugees left their lands under the orders of Arab leaders, some Israeli scholars have challenged this view in recent years.[63]

Shitrit/Shertok intervention

The Israeli cabinet reportedly knew nothing about the expulsion plan until Bechor Shitrit, Minister for Minority Affairs, appeared unannounced in Ramle on 12 July. He was shocked when he realized troops were organizing expulsions. He returned to Tel Aviv for a meeting with Foreign Minister Moshe Shertok, who met with Ben Gurion to agree on guidelines for the treatment of the residents, though Morris writes that Ben Gurion apparently failed to tell Shitrit or Shertok that he himself was the source of the expulsion orders. Gelber disagrees with Morris's analysis, arguing that Ben-Gurion's agreement with Shitrit and Shertok is evidence that expulsion was not his intention, rather than evidence of his duplicity, as Morris implies.[62] The men agreed the townspeople should be told that anyone who wanted to leave could do so, but that anyone who stayed was responsible for himself and would not be given food. Women, children, the old, and the sick were not to be forced to leave, and the monasteries and churches must not be damaged, though no mention was made of the mosques. Ben-Gurion passed the order to the IDF General Staff, who passed it to Dani HQ at 23:30 hours on 12 July, ten hours after the expulsion orders were issued; Morris writes that there was an ambiguity in the instruction that women, children and the sick were not to be forced to go: the word "lalechet" can mean either "go" or "walk". Satisfied that the order had been passed on, Shertok believed he had managed to avert the expulsions, not realizing that, even as he was discussing them in Tel Aviv, they had already begun.[64]

The departure

Thousands of Ramle residents began moving out of the town on foot, or in trucks and buses, between 10 and 12 July. The IDF used its own vehicles and confiscated Arab ones to move them.[65] Morris writes that, by 13 July, the wishes of the IDF and those of the residents in Lydda had dovetailed. Over the past three days, the townspeople had undergone aerial bombardment, ground invasion, had seen grenades thrown into their homes and hundreds of residents killed, had been living under a curfew, had been abandoned by the Arab Legion, and the able-bodied men had been rounded up. Morris writes they had concluded that living under Israeli rule was not sustainable.[66] Spiro Munayyer, an eyewitness, wrote that the important thing was to get out of the city.[29] A deal was reached with an IDF intelligence officer, Shmarya Guttman, normally an archeologist, that the residents would leave in exchange for the release of the prisoners; according to Guttman, he went to the mosque himself and told the men they were free to join their families.[67] Town criers and soldiers walked or drove around the town instructing residents where to gather for departure.[68]

Notwithstanding that an agreement may have been reached, Morris writes that the troops understood that what followed was an act of deportation, not a voluntary departure. While the residents were still in the town, IDF radio traffic had already started calling them "refugees" (plitim).[69] Operation Dani HQ told the IDF General Staff/Operations at noon on 13 July that "[the troops in Lydda] are busy expelling the inhabitants [oskim begeirush hatoshavim]," and told the HQs of Kiryati, 8th and Yiftah brigades at the same time that, "enemy resistance in Ramle and Lydda has ended. The eviction [pinui]" of the inhabitants... has begun."[70]

The march

Lydda's residents began moving out on the morning of 13 July. They were made to walk, perhaps because of their earlier resistance, or simply because there were no vehicles left. They walked six to seven kilometers to Beit Nabala, then 10–12 more to Barfiliya, along dusty roads in temperatures of 30–35°C, carrying their children and portable possessions in carts pulled by animals or on their backs.[72] According to Shmarya Guttman, an IDF soldier, warning shots were occasionally fired.[73] Some were stripped of their valuables en route by Israeli soldiers at checkpoints.[73] Another IDF soldier described how possessions and people were slowly abandoned as the refugees grew tired or collapsed: "To begin with [jettisoning] utensils and furniture, and in the end, bodies of men, women, and children, scattered along the way."[73]

Haj As'ad Hassouneh, described by Saleh Abd al-Jawad as "a survivor of the death march", shared his recollection in 1996: "The Jews came and they called among the people: "You must go." "Where shall we go?" "Go to Barfilia." ... the spot you were standing on determined what if any family or possession you could get; any to the west of you could not be retrieved. You had to immediately begin walking and it had to be to the east. ... The people were fatigued even before they began their journey or could attempt to reach any destination. No one knew where Barfilia was or its distance from Jordan. ... The people were also fasting due to Ramadan because they were people of serious belief. There was no water. People began to die of thirst. Some women died and their babies nursed from their dead bodies. Many of the elderly died on the way. ... Many buried their dead in the leaves of corn".[74]

After three days of walking, the refugees were picked up by the Arab Legion and driven to Ramallah.[75] Reports vary regarding how many died. Many were elderly people and young children who died from the heat and exhaustion.[58] Morris has written that it was a "handful and perhaps dozens."[76] Glubb wrote that "nobody will ever know how many children died."[73] Nimr al Khatib estimated that 335 died based on hearsay.[73] Walid Khalidi gives a figure of 350, citing Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref.[77] The expulsions clogged the roads eastward. Morris writes that IDF thinking was simple and cogent. They had just taken two major objectives and were out of steam. The Arab Legion had been expected to counter-attack, but the expulsions thwarted it: the roads were now cluttered, and the Legion was suddenly responsible for the welfare of an additional tens of thousands of people.[73]

Looting of refugees and the towns

The Sharett-Ben Gurion guidelines to the IDF had specified there was to be no robbery, but numerous sources spoke of widespread looting. The Economist wrote on 21 August that year: "The Arab refugees were systematically stripped of all their belongings before they were sent on their trek to the frontier. Household belongings, stores, clothing, all had to be left behind."[78] Aharon Cohen, director of Mapam's Arab Department, complained to Yigal Allon months after the deportations that troops had been told to remove jewellery and money from residents so that they would arrive at the Arab Legion without resources, thereby increasing the burden of looking after them. Allon replied that he knew of no such order, but conceded it as a possibility.[79]

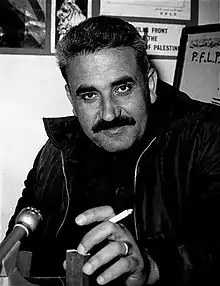

George Habash, who later founded the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, was born in Lydda to a Greek Orthodox family. He was in his second year at medical school in Beirut at the time, but returned to Lydda when he heard the Israelis had arrived in Jaffa, and was subsequently one of those expelled. Recalling the events of 1948 in 1990, he said that the Israelis took watches, jewellery, gold, and wallets from the refugees, and that he witnessed a neighbour of his shot and killed because he refused to be searched; he said the man's sister, who also saw what happened, died during the march from the shock, exposure and thirst.[80]

As the residents left, the sacking of the cities began. The Yiftah brigade commander, Lt. Col. Schmuel "Mula" Cohen, wrote of Lydda that, "the cruelty of the war here reached its zenith."[81] Bechor Sheetrit, the Minister for Minority Affairs, said the army removed 1,800 truckloads of property from Lydda alone. Dov Shafrir was appointed Israel's Custodian of Absentee Property, supposedly charged to protect and redistribute Palestinian property, but his staff were inexperienced and unable to control the situation.[82] The looting was so extensive that the 3rd Battalion had to be withdrawn from Lydda during the night of 13–14 July, and sent for a day to Ben Shemen for kinus heshbon nefesh, a conference to encourage soul-searching. Cohen forced them to hand over their loot, which was thrown onto a bonfire and destroyed, but the situation continued when they returned to town. Some were later prosecuted.[83]

There were also allegations that Israeli soldiers had raped Palestinian women. Ben-Gurion referred to them in his diary entry for 15 July 1948: "The bitter question has arisen regarding acts of robbery and rape [o'nes ("אונס")] in the conquered towns ..."[84] Israeli writer Amos Kenan, who served as a platoon commander of the 82d Regiment of the Israeli Army brigade that conquered Lydda told The Nation on 6 February 1989: "At night, those of us who couldn't restrain ourselves would go into the prison compounds to fuck Arab women. I want very much to assume, and perhaps even can, that those who couldn't restrain themselves did what they thought the Arabs would have done to them had they won the war."[85] Kenan said he heard of only one woman who complained. A court-martial was arranged, he said, but in court, the accused ran the back of his hand across his throat, and the woman decided not to proceed.[85] The allegations were given little consideration by the Israeli government. Agriculture Minister Aharon Zisling told the Cabinet on 21 July: "It has been said that there were cases of rape in Ramle. I could forgive acts of rape but I won't forgive other deeds, which appear to me much graver. When a town is entered and rings are forcibly removed from fingers and jewellery from necks—that is a very grave matter."[86]

Stuart Cohen writes that central control over the Jewish fighters was weak. Only Yigal Allon, commander of the IDF, made it standard practice to issue written orders to commanders, including that violations of the laws of war would be punished. Otherwise, trust was placed, and sometimes misplaced, in what Cohen calls intuitive troop decency. He adds that, despite the alleged war crimes, the majority of the IDF behaved with decency and civility.[87] Yitzhak Rabin wrote in his memoirs that some refused to take part in the evictions.[88]

Aftermath

In Ramallah, Amman, and elsewhere

Tens of thousands of Palestinians from Lydda and Ramle poured into Ramallah. For the most part, they had no money, property, food, or water, and represented a health risk, not only to themselves. The Ramallah city council asked King Abdullah to remove them.[89] Some of the refugees reached Amman, the Gaza Strip, Lebanon, and the Upper Galilee, and all over the area there were angry demonstrations against Abdullah and the Arab Legion for their failure to defend the cities. People spat at Glubb, the British commander of the Arab Legion, as he drove through the West Bank, and wives and parents of Arab Legion soldiers tried to break into King Abdullah's palace.[90] Alec Kirkbride, the British ambassador in Amman, described one protest in the city on 18 July:

A couple of thousand Palestinian men swept up the hill toward the main [palace] entrance ... screaming abuse and demanding that the lost towns should be reconquered at once ... The King appeared at the top of the main steps of the building; he was a short, dignified figure wearing white robes and headdress. He paused for a moment, surveying the seething mob before, [then walked] down the steps to push his way through the line of guardsmen into the thick of the demonstrators. He went up to a prominent individual, who was shouting at the top of his voice, and dealt him a violent blow to the side of the head with the flat of his hand. The recipient of the blow stopped yelling ... the King could be heard roaring: so, you want to fight the Jews, do you? Very well, there is a recruiting office for the army at the back of my house ... go there and enlist. The rest of you, get the hell down the hillside!" Most of the crowd got the hell down the hillside.[91]

Morris writes that, during a meeting in Amman on 12–13 July of the Political Committee of the Arab League, delegates—particularly from Syria and Iraq—accused Glubb of serving British, or even Jewish, interests, with his excuses about troop and ammunition shortages. Egyptian journalists said he had handed Lydda and Ramle to the Jews. Perie-Gordon, Britain's acting minister in Amman, told the Foreign Office there was a suspicion that Glubb, on behalf of the British government, had lost Lydda and Ramle deliberately to ensure that Transjordan accept a truce. King Abdullah indicated that he wanted Glubb to leave, without actually asking him to—particularly after Iraqi officers alleged that the entire Hashemite house was in the pay of the British—but London asked him to stay on. Britain's popularity with the Arabs reached an all-time low.[92] The United Nations Security Council called for a ceasefire to begin no later than 18 July, with sanctions to be levelled against transgressors. The Arabs were outraged: "No justice, no logic, no equity, no understanding, but blind submission to everything that is Zionist," Al-Hayat responded, though Morris writes that cooler heads in the Arab world were privately pleased that they were required not to fight, given Israel's obvious military superiority.[93]

Situation of the refugees

Morris writes that the situation of the 400,000 Palestinian Arabs who became refugees that summer—not only those from Lydda and Ramle—was dire, camping in public buildings, abandoned barracks, and under trees.[94] Count Folke Bernadotte, the United Nations mediator in Palestine, visited a refugee camp in Ramallah and said he had never seen a more ghastly sight.[95] Morris writes that the Arab governments did little for them, and most of the aid that did reach them came from the West through the Red Cross and Quakers. A new UN body was set up to get things moving, which in December 1949 became the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), which many of the refugees and their descendants, now standing at four million, still depend on.[94] Bernadotte's mediation efforts—which resulted in a proposal to split Palestine between Israel and Jordan, and to hand Lydda and Ramle to King Abdullah—ended on 17 September 1948, when he was assassinated by four Israeli gunmen from Lehi, an extremist Zionist faction.[96]

Lausanne Conference

The United Nations convened the Lausanne Conference of 1949 from April to September 1949 in part to resolve the refugee question. On 12 May 1949, the conference achieved its only success when the parties signed the Lausanne Protocol on the framework for a comprehensive peace, which included territories, refugees, and Jerusalem. Israel agreed in principle to allow the return of all of Palestinian refugees because the Israelis wanted United Nations membership, which required the settlement of the refugee problem. Once Israel was admitted to the UN, it retreated from the protocol it had signed, because it was completely satisfied with the status quo, and saw no need to make any concessions with regard to the refugees or on boundary questions. Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett had hoped for a comprehensive peace settlement at Lausanne, but he was no match for Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, who saw the armistice agreements that stopped the fighting with the Arab states as sufficient, and put a low priority on a permanent peace treaty.[97] On 3 August 1949, the Israeli delegation proposed the repatriation of 100,000 refugees, but not to their former homes, which had been destroyed or given to Jewish refugees from Europe; Israel would specify where the refugees would be relocated and the specific economic activities the refugees would be permitted to engage in. Also, the 100,000 would include 25,000 who had already returned illegally, so the actual total was only 75,000. The Americans felt it too low: they wanted to see 200,000-250,000 refugees taken back. The Arabs considered the Israeli offer was "less than token." When the '100,000 plan' was announced, the reaction of Israeli newspapers and political parties was uniformly negative. Soon after, the Israelis announced their offer had been withdrawn.[98]

Resettlement of the cities

On 14 July 1948 the IDF told Ben-Gurion that "not one Arab inhabitant" remained in Ramla or Lod, as they were now called. In fact, several hundred remained, including city workers who maintained essential city services like water service, and workers with expertise with the railroad train yards and the airport, the elderly, the ill and some Christians, and others who return to their homes over the following months. In October 1948 the Israeli military governor of Ramla-Lod reported that 960 Palestinians were living in Ramla, and 1,030 in Lod. Military rule in the towns ended in April 1949.[99]

Nearly 700,000 Jews immigrated to Israel between May 1948 and December 1951 from Europe, Asia and Africa, doubling the state's Jewish population; in 1950 Israel passed the Law of Return, offering Jews automatic citizenship.[100] The immigrants were assigned Palestinian homes—in part because of the inevitable housing shortage, but also as a matter of policy to make it harder for former residents to reclaim them—and could buy refugees' furniture from the Custodian for Absentees' Property.[101] Jewish families were occasionally placed in houses belonging to Palestinians who still lived in Israel, the so-called "present absentees," regarded as physically present but legally absent, with no legal standing to reclaim their property.[100] By March 1950 there were 8,600 Jews and 1,300 Palestinian Arabs living in Ramla, and 8,400 Jews and 1,000 Palestinians in Lod. Most of the Jews who settled in the towns were from Asia or North Africa.[102]

The Palestinian workers allowed to remain in the cities were confined to ghettos. The military administrator split the region into three zones—Ramla, Lod, and Rakevet, a neighbourhood in Lod established by the British for rail workers—and declared the Arab areas within them "closed," with each closed zone run by a committee of three to five members.[103] Many of the town's essential workers were Palestinians. The military administrators did satisfy some of their needs, such as building a school, supplying medical aid, allocating them 50 dunams for growing vegetables, and renovating the interior of the Dahmash mosque, but it appears the refugees felt like prisoners; Palestinian train workers, for example, were subject to a curfew from evening until morning, with periodic searches to make sure they had no guns.[104] One wrote an open letter in March 1949 to the Al Youm newspaper on behalf of 460 Muslim and Christian train workers: "Since the occupation, we continued to work and our salaries have still not been paid to this day. Then our work was taken from us and now we are unemployed. The curfew is still valid ... [W]e are not allowed to go to Lod or Ramla, as we are prisoners. No one is allowed to look for a job but with the mediation of the members of the Local Committee ... we are like slaves. I am asking you to cancel the restrictions and to let us live freely in the state of Israel.[105]

Artistic reception

The Palestinian artist Ismail Shammout (1930–2006) was 19 years old when he was expelled from Lydda. He created a series of oil paintings about the march, the best known of which is Where to ...? (1953), which enjoys iconic status among Palestinians. A life-size image of a man dressed in rags holds a walking stick in one hand, the wrist of a child in the other, a toddler on his shoulder, with a third child behind him, crying and alone. There is a withered tree behind him, and in the distance the skyline of an Arab town with a minaret. Gannit Ankori writes that the absent mother is the lost homeland, the children its orphans.[106]

By November 1948 the IDF had been accused of atrocities in a number of towns and villages, to the point where David Ben-Gurion had to appoint an investigator. Israeli poet Natan Alterman (1910–1970) wrote about the allegations in his poem Al Zot ("On This"), published in Davar on 19 November 1948, about a soldier on a jeep machine-gunning an Arab, referring to the events in Lydda, according to Morris. Two days later Ben-Gurion sought Alterman's permission for the Defence Ministry to distribute the poem throughout the IDF:[107]

Let us sing then also about "delicate incidents"

For which the true name, incidentally, is murder

Let songs be composed about conversations with sympathetic interlocutors

who with collusive chuckles make concessions and grant forgiveness.[108]

- Al Zot in Hebrew, www.education.gov.il, accessed 1 December 2010.

Four figures after the exodus

Yigal Allon, who led Operation Dani and may have ordered the expulsions, became Israel's deputy prime minister in 1967. He was a member of the war cabinet during the 1967 Arab Israeli Six-Day War, and the architect of the post-war Allon Plan, a proposal to end Israel's occupation of the West Bank. He died in 1980.[109]

Yitzhak Rabin, Allon's operations officer, who signed the Lydda expulsion order, became Chief of Staff of the IDF during the Six-Day War, and Israel's prime minister in 1974 and again in 1992. He was assassinated in 1995 by a right-wing Israeli radical opposed to making peace with the PLO.[57]

Khalil al-Wazir, the grocer's son expelled from Ramle, became one of the founders of Yasser Arafat's Fatah faction within the PLO, and specifically of its armed wing, Al-Assifa. He organised the PLO's guerrilla warfare and the Fatah youth movements that helped spark the First Intifada in 1987. He was assassinated by Israeli commandos in Tunis in 1988.[110]

George Habash, the medical student expelled from Lydda, went on to lead one of the best-known of the Palestinian militant groups, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. In September 1970 he masterminded the hijacking of four passenger jets bound for New York, an attack that put the Palestinian cause on the map. The PFLP was also behind the 1972 Lod Airport massacre, in which 27 people died, and the 1976 hijacking of an Air France flight to Entebbe, which famously led to the IDF's rescue of the hostages. Habash died of a heart attack in Amman in 2008.[111]

Historiography

Benny Morris argues that Israeli historians from the 1950s throughout the 1970s—who wrote what he calls the "Old History"—were "less than honest" about what had happened in Lydda and Ramle.[113] Anita Shapira calls them the Palmach generation: historians who had fought in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and who thereafter went to work for the IDF's history branch, where they censored material other scholars had no access to. For them, Shapira writes, the Holocaust and the Second World War—including the experience of Jewish weakness in the face of persecution—made the fight for land between the Arabs and Jews a matter of life and death, the 1948 war the "tragic and heroic climax of all that had preceded it," and Israeli victory an "act of historical justice."[112]

The IDF's official history of the 1948 war, Toldot Milhemet HaKomemiyut ("History of the War of Independence"), published in 1959, said that residents of Lydda had violated the terms of their surrender, and left because they were afraid of Israeli retribution. The head of the IDF history branch, Lt. Col Netanel Lorch, wrote in The Edge of the Sword (1961) that they had requested safe conduct from the IDF; American political scientist Ian Lustick writes that Lorch admitted in 1997 that he left his post because the censorship made it impossible to write good history.[114] Another employee of the history branch, Lt. Col. Elhannan Orren, wrote a detailed history of Operation Dani in 1976 that made no mention of expulsions.[113]

Arab historians published accounts, including Aref al-Aref's Al Nakba, 1947–1952 (1956–1960), Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib's Min Athar al-Nakba (1951), and several papers by Walid Khalidi, but Morris writes that they suffered from a lack of archival material; Arab governments have been reluctant to open their archives, and the Israeli archives were at that point still closed.[115] The first person in Israel to acknowledge the Lydda and Ramle expulsions, writes Morris, was Yitzhak Rabin in his 1979 memoirs, though that part of his manuscript was removed by government censors.[113] The 30-year rule of Israel's Archives Law, passed in 1955, meant that hundreds of thousands of government documents were released throughout the 1980s, and a group calling itself the "New Historians" emerged, most of them born around 1948. They interpreted the history of the war, not in terms of European politics, the Holocaust, and Jewish history, but solely within the context of the Middle East. Shapira writes that they focused on the 700,000 Palestinian Arabs who were uprooted by the war, not on the 6,000 Jews who died during it, and assessed the behavior of the Jewish state as they would that of any other.[116] Between 1987 and 1993, four of these historians in particular—Morris himself, Simha Flapan, Ilan Pappé, and Avi Shlaim—three of them Oxbridge-trained, published a series of books that changed the historiography of the Palestinian exodus. According to Lustick, although it was known in academic circles that the Palestinians had left because of expulsions and intimidation, it was largely unknown to Israeli Jews until Morris's The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949 appeared in 1987.[117]

Their work is not without its critics, most notably Israeli historian Efraim Karsh, who writes that there was more voluntary Palestinian flight than Morris and the others concede. He acknowledges that there were expulsions, particularly in Lydda, though he argues—as does Morris—that they resulted from decisions made in the heat of battle, and account for a small percentage of the overall exodus.[118] Karsh argues that the New Historians have turned the story of the birth of Israel upside down, making victims of the Arab aggressors, though he acknowledges that the New History is now widely accepted.[119] Ari Shavit devotes a chapter of his book My Promised Land (2013) to the expulsion, and calls the events "our black box, . . In it lies the dark secret of Zionism."[120] The positions of Karsh and Morris, though they disagree, contrast in turn with those of Ilan Pappé and Walid Khalidi, who argue not only that there were widespread expulsions, but also that they were not the result of ad hoc decisions. Rather, they argue, the expulsions were part of a deliberate strategy, known as Plan Dalet and conceived before Israel's declaration of independence, to transfer the Arab population and seize their land—in Pappé's words, to ethnically cleanse the country.[121]

Lod and Ramla today

As of 2013 around 69,000 people were living in Ramla, which became briefly known around the world in 1962, when former SS officer Adolf Eichmann was hanged in Ramla prison in May that year.[122] The population in Lod as of 2010 was officially around 45,000 Jews and 20,000 Arabs; its main industry is its airport, renamed Ben Gurion International Airport in 1973.[123] Beth Israel immigrants from Ethiopia were housed there in the 1990s, increasing the ethnic tension in the city which, together with the economic deprivation, make the town "the most likely place to explode," according to Arnon Golan, Israeli's foremost expert on ethnically-mixed cities.[124] In 2010 a three-meter-high wall was built to separate the Jewish and Arab neighbourhoods.[123]

The Arab community has complained that, when Arabs became a majority in Lod's Ramat Eshkol suburb, the local school was closed rather than turned into an Arab-sector school, and in September 2008 it was re-opened as a yeshiva, a Jewish religious school. The local council acknowledges that it wants Lod to become a more Jewish city. In addition to the Arabs officially registered, a fifth of the overall population are Bedouin, who arrived in Lod in the 1980s when they were moved off land in the Negev, according to Nathan Jeffay.They live in dwellings deemed illegal by Israeli authorities on agricultural land, unregistered and with no municipal services.[125]

The refugees are occasionally able to visit their former homes. Zochrot, an Israeli group that researches former Palestinian towns, visited Lod in 2003 and 2005, erecting signs in Hebrew and Arabic depicting its history, including a sign on the wall of the former Arab ghetto. The visits are met with a mixture of interest and hostility.[126] Father Oudeh Rantisi, a former mayor of Ramallah who was expelled from Lydda in 1948, visited his family's former home for the first time in 1967:

As the bus drew up in front of the house, I saw a young boy playing in the yard. I got off the bus and went over to him. "How long have you lived in this house?" I asked. "I was born here," he replied. "Me too," I said ...[127]

Notes

- Chamberlin, P.T. (2012). The Global Offensive: The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post-Cold War Order. Oxford Studies in International History. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-997711-6. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

On a visit home in 1948, Habash was caught in the Jewish attack on Lydda and, along with his family, forced to leave the city in the mass expulsion that came to be known as the Lydda Death March.

- Holmes, Richard; Strachan, Hew; Bellamy, Chris; Bicheno, Hugh, eds. (2001), The Oxford companion to military history, Oxford University Press, p. 64, ISBN 9780198662099,

On 12 July, the Arab inhabitants of the Lydda-Ramle area, amounting to some 70,000, were expelled in what became known as the Lydda Death March.

- Expulsion of the Palestinians—Lydda and Ramleh in 1948, by Donald Neff

- Roza El-Eini,Mandated Landscape: British Imperial Rule in Palestine, 1929–1948, Routledge 2006 p.436

- The Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press 2004, p. 425.

- For population figures, see Morris 2004, p. 425, 434. He writes that, in July 1948 before the invasion, Lydda and Ramle had a population of 50,000–70,000, 20,000 of whom were refugees from Jaffa and the surrounding area (p. 425). All were expelled, except for a few elderly or sick people, some Christians, and some who were retained to work; others managed to sneak back in, so that by mid-October 1948 there were around 2,000 Palestinians living in both towns (p. 434).

- For the name change, see Yacobi 2009, p. 29. Yacobi writes that Lod was Lydda's biblical name.

- Palestinians called Lydda al-Ludd. Lydda was the Latin form of its name, which it was widely known by. See Sharon 1983, p. 798.

- Ramle can also be written as Ramleh; it known as Ramla by the Israelis, and should not be confused with Ramallah, the administrative center of the Palestinian National Authority.

- Benny Morris, The Palestine Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press 2004 p.4.

- Benny Morris, The Palestine Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press 2004 p.425.

- Kadish, Alon; Sela, Avraham (2005). "Myths and historiography of the 1948 Palestine War revisited: the case of Lydda".

- Rabin, Yitzhak; The Rabin Memoirs. University of California Press, 1996 p.383: 'Allon and I held a consultation. I agreed that it was essential to drive the inhabitants out. We took them on foot toward the Ben Horon road, assuming that the Arab Legion would be obliged to look after them, thereby shouldering logistic difficulties which would burden its fighting capacity, making things easier for us.'

- 1948: A History of the First Arab–Israeli War, by Benny Morris

- Henry Laurens, La Question de Palestine, vol.3, Fayard 2007 p.145.

- The death toll in Lydda:

- Morris 2004, p. 426: 11 July—Six dead and 21 wounded on the Israeli side, and "dozens of Arabs (perhaps as many as 200)".

- Morris 2004, p. 452, footnote 68: Third Battalion intelligence puts the figure at 40 Palestinians dead, but perhaps referring only to the numbers they had killed themselves.

- Morris 2004, p. 428: 12 July—Israeli troops were ordered to shoot at anyone seen on the streets: during that incident, 3–4 Israelis were killed and around a dozen wounded. On the Arab side, 250 dead and many wounded, according to the IDF.

- Morris, Benny (1987). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949. Cambridge Middle East Library. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0521338899.

- Morris 2004, pp. 432–434.

- Also see Gilbert 2008, pp. 218–219.

-

For the number of refugees who died during the march:

- Morris 1989, pp. 204–211: "Quite a few refugees died – from exhaustion, dehydration and disease."

- Morris 2003, p. 177: "a handful, and perhaps dozens, died of dehydration and exhaustion."

- Morris 2004, p. 433: "Quite a few refugees died on the road east," attributing a figure of 335 dead to Muhammad Nimr al Khatib, who Morris writes was working from hearsay.

- Henry Laurens, La Question de Palestine, vol.3, Fayard 2007 p.145 states that Aref al-Aref set the figure at 500, among an estimated 1300 who died either in fighting in Lydda or on the march that ensued."Le nombre total dee morts se monte à 1 300:800 lors des combats de la ville, le reste dans l'exode.".

- Khalidi 1998 Archived 23 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 80–98: 350 dead, citing an estimate from Aref al-Aref.

- Nur Masalha 2003, p. 47 writes that 350 died.

- For the use of the term "ethnic cleansing," see, for example, Pappé 2006.

- On whether what occurred in Lydda and Ramle constituted ethnic cleansing:

- Morris 2008, p. 408: "although an atmosphere of what would later be called ethnic cleansing prevailed during critical months, transfer never became a general or declared Zionist policy. Thus, by war's end, even though much of the country had been 'cleansed' of Arabs, other parts of the country—notably central Galilee—were left with substantial Muslim Arab populations, and towns in the heart of the Jewish coastal strip, Haifa and Jaffa, were left with an Arab minority."

- Spangler 2015, p. 156: "During the Nakba, the 1947 [sic] displacement of Palestinians, Rabin had been second in command over Operation Dani, the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian towns of towns of Lydda and Ramle."

- Schwartzwald 2012, p. 63: "The facts do not bear out this contention [of ethnic cleansing]. To be sure, some refugees were forced to flee: fifty thousand were expelled from the strategically located towns of Lydda and Ramle ... But these were the exceptions, not the rule, and ethnic cleansing had nothing to do with it."

- Golani and Manna 2011, p. 107: "The expulsion of some 50,000 Palestinians from their homes ... was one of the most visible atrocities stemming from Israel's policy of ethnic cleansing."

- That it was one-tenth of the overall exodus, see Morris 1986, p. 82.

- That most of the immigrants to Lydda and Ramle were from Asia and North Africa, see Golan 2003.

- That refugees were settled in the empty homes to stop them from being reclaimed, see Morris 2008, p. 308, and Yacobi 2009, p. 45.

- Ari Shavit, Lydda, 1948; A city, a massacre, and the Middle East today, 21 October 2013, The New Yorker: "Lydda is the black box of Zionism. The truth is that Zionism could not bear the Arab city of Lydda. From the very beginning, there was a substantial contradiction between Zionism and Lydda. If Zionism was to exist, Lydda could not exist. If Lydda was to exist, Zionism could not exist. In retrospect, it's all too clear. When Siegfried Lehmann arrived in the Lydda Valley, in 1927, he should have seen that if a Jewish state was to exist in Palestine an Arab Lydda could not exist at its center. He should have known that Lydda was an obstacle blocking the road to a Jewish state, and that one day Zionism would have to remove it. But Dr. Lehmann did not see, and Zionism chose not to know. For decades, Jews succeeded in hiding from themselves the contradiction between their national movement and Lydda...When one opens the black box, one understands that, whereas the massacre at the mosque could have been triggered by a misunderstanding brought about by a tragic chain of accidental events, the conquest of Lydda and the expulsion of Lydda's population were no accident. Those events were a crucial phase of the Zionist revolution, and they laid the foundation for the Jewish state. Lydda is an integral and essential part of the story. And, when I try to be honest about it, I see that the choice is stark: either reject Zionism because of Lydda or accept Zionism along with Lydda."

- Morris 2008, p. 37ff.

- For Lydda's age, see Schwartz 1991, p. 39.

- According to Christian legend, Lydda was the birth place and burial ground of Saint George (ca. 270–303 CE), the patron saint of England; see Sharon 1983, p. 799. Sharon (p. 798) writes that the town may date back to King Thutmos III of Egypt. Also see Gordon 1907, p. 3.

- For Ramle, see Golan 2003.

- For Golan's article about Ramle being a focal point, see Golan 2003.

- For the siege of Jerusalem, see Gelber 2006, p. 145.

- See Schmidt, 12 June 1948 for the temporary lifting of the siege.

- For the attacks on Ramle and Lydda, see Morris 2004, p. 424.

- For Ben-Gurion and the two thorns, see Morris 2004, pp. 424–425, and Segev 2000 Archived 13 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Segev writes that, just after Ben-Gurion's "two thorns" statement to the cabinet, six lines have been erased from the transcript. Segev interprets this to mean that expulsions were discussed.

- For the primary source, see Ben-Gurion 1982, "16 June 1948," p. 525.

- Morris 2004, pp. 423–424.

- Kimche, Jon; Kimche, David (1960). A Clash of Destinies. The Arab-Jewish War and the Founding of the State of Israel. Frederick A. Praeger. p. 225. LCCN 60-6996. OCLC 1348948. (number of men)

- For the launching of Operation Dani and the forces assembled, see Morris 2008, p. 286.

- For the hiring of Allon and Rabin, see Shipler, The New York Times, 23 October 1979.

- For the period known as the Ten Days, see Morris 2008, p. 273ff.

- Morris 2004, p. 425.

- Morris 2003, p. 118.

- Kadish and Sela 2005.

- Khalidi, Walid (1998). "The Fall of Lydda" (PDF). Journal of Palestine Studies. 27 (4): 81. doi:10.1525/jps.1998.27.4.00p0007d. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Morris 2008, pp. 286, 289.

- That the IDF ignored that the Legion was "on a defensive footing," see Gelber 2006, p. 158.

- Gelber 2006, p. 159.

- Morris 1986, p. 86: The leaflets said: "You have no chance of receiving help. We intend to conquer the towns. We have no intention of harming persons or property. [But] whoever attempts to oppose us—will die. He who prefers to live must surrender.

- Formal surrender discussed in a telephone message from Dani HQ, 12 July 1948, 10:30 am, cited in Morris 2004, p. 427.

- For the New York Times account of the surrender, see Currivan, The New York Times, 12 July 1948.

- Dimbleby and McCullin 1980, pp. 88–89. He said: "The whole village went to the church. ... I remember the archbishop standing in front of the church. He was holding a white flag. ... Afterwards we came out and the picture will never be erased from my mind. There were bodies scattered on the road and between the houses and the side streets. No one, not even women or children, had been spared if they were out in the street. ..."

- Koestler 1949, pp. 270–271. He wrote: "The Arabs were hanging about in the streets much as usual, except for a few hundred youths of military age who have been put into a barbed wire cage and were taken off in lorries to an internment camp. Their veiled mothers and wives were carrying food and water to the cage, arguing with the Jewish sentries and pulling their sleeves, obviously quite unafraid. ... Groups of Arabs came marching down the main street with their arms above their heads, grinning broadly, without any guards, to give themselves up. The one prevailing feeling among all seemed to be that as far as Ramleh was concerned the war was over, and thank God for it."

- Bilby 1950, p. 43.

- Shapira 2007, p. 225.

- Morris 2004, p. 426.

- Currivan, The New York Times, 12 July 1948.

- The casualty figures vary widely. The figure from Dayan is cited in Kadish and Sela 2005.

- There were dozens dead and wounded, "perhaps as many as 200," according to Morris 2004, p. 426 and p. 452, footnote 68, citing Kadish, Sela, and Golan 2000, p. 36.

- "[A]bout 40 dead and a large number of wounded," according to Third Battalion intelligence, though it is not clear whether they meant 40 killed by the Third Battalion alone; see Morris 2004, p. 452, footnote 68.

- Six died and 21 were wounded on the Israeli side, according to Morris 2004, p. 426, again citing Kadish, Sela, and Golan 2000, p. 36.

- For the IDF quote, see Morris 2004, p. 427.

- For the 4,000 in the Great Mosque, see Kadish and Sela 2005.

- Gelber 2004, p. 23.

- Arnon Golan (October 2003). "Lydda and Ramle: From Palestinian-Arab to Israeli Towns, 1948-67". Middle Eastern Studies. 39 (4): 121–139. doi:10.1080/00263200412331301817.

- Kadish and Sela 2005.

- Gelber 2006, p. 162.

- Shapira 2007, p. 227.

- Khalidi, Walid (1998). "The Fall of Lydda" (PDF). Journal of Palestine Studies. 27 (4): 81. doi:10.1525/jps.1998.27.4.00p0007d. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012. calls it "an orgy of indiscriminate killing."

- Kadish and Sela 2005 call it "an intense battle where the demarcation between civilians, irregular combatants and regular army units hardly existed."

- Morris 2004, p. 427.

- Morris 1986, p. 87.

- Poole, John W.; Kadish, Alon; Sela, Avraham; Guclu, Yucel (1 January 2006). "Communications". Middle East Journal. 60 (3): 620–622. JSTOR 4330311.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Morris 2004, p. 428, 453, footnote 81. For more casualty figures, see Kadish and Sela 2005.

- page=93–4.

- Noam Sheizaf, 'Despite efforts to erase it, the Nakba's memory is more present than ever in Israel,' +972 magazine 15 May 2013.

- For a discussion about which mosque this happened in, and for the 95 bodies, see Kadish and Sela 2005, particularly footnote 40.

- Morris 2004, p. 428: "dozens" were shot and killed

- Morris 2004, p. 453, footnote 81, cites Kadish, Sela and Golan's The Conquest, who say it was a battle that took place in the mosque, not a massacre. He adds that Kadish et al. acknowledge that women, children, and unarmed older men were among the dead.

- An eyewitness, Fayeq Abu Mana, 20 years old at the time, told an Israeli group in 2003 that he had been involved in removing the bodies; see Zochrot 2003.

- Morris 2004, p. 434.

- Morris 2004, p. 415.

- Shavit 2004.

- For his having signed the order, see Morris 2004, p. 429.

- Shipler, The New York Times, 23 October 1979.

- Morris 1986, p. 90, footnote 31.

- Morris 2004, p. 429.

- The orders for Lydda were from Dani HQ to Yiftah Brigade HQ and 8th Brigade HQ, and to Kiryati Brigade at around the same time.

- "1. The inhabitants of Lydda must be expelled quickly without attention to age. They should be directed towards Beit Nabala. Yiftah [Brigade HQ] must determined the method and inform Dani HQ and 8th Brigade HQ.

- "2. Implement immediately (Prior 1999, p. 205).

- The IDF archives holds two nearly identical copies of the expulsion order. According to Morris 2004, p. 454, footnote 89, Yigal Allon denied in 1979 that there had been such an order, or an expulsion, saying that the order to evacuate the civilian population of Lydda and Ramle came from the Arab Legion.

- A telegram from Kiryati Brigade HQ to Zvi Aurback, its officer in charge of Ramle, read:

- 1. In light of the deployment of 42nd Battalion out of Ramle – you must take [over responsibility] for the defence of the town, the transfer of prisoners [to PoW camps] and the emptying of the town of its inhabitants.

- 2. You must continue the sorting out of the inhabitants, and send the army-age males to a prisoner of war camp. The old, women and children will be transported by vehicle to al Qubab and will be moved across the lines – [and] from there continue on foot.." (Kiryati HQ to Aurbach, Tel Aviv District HQ (Mishmar) etc., 14:50 hours, 13 July 1948, Haganah Archive, Tel Aviv), cited in Morris 2004, p. 429.

- Shipler, The New York Times, 25 October 1979.

- Shapira 2007, p. 232: Allon gave a lecture on the war in 1950, during which Anita Shapira writes that he was uncharacteristically frank. He said he blamed the Palestinian departure on three factors. First, they fled because they were projecting: the Arabs imagined that the Jews would do to them what they would do to the Jews if positions were reversed. Second, Arab and British leaders encouraged people to leave their towns so as not to be taken hostage, so they could return to fight another day. Third, there were some cases of expulsion, though these were not the norm. In Lydda and Ramle, the Arab Legion continued to attack Israeli outposts in the hope of reconnecting with their troops in Lydda, he said. When the expulsions started, the attacks died down. To leave the towns' hostile populations in place would be to risk their use by the Legion to coordinate further attacks. Allon said he had no regrets: "War is war." Allon described it elsewhere as a "provoked exodus," rather than an expulsion; see Kadish and Sela 2005.

- Also see Morris 2004, p. 454, footnote 89.

- Gelber 2006, pp. 162–163.

- Avi Shlaim. "The War of the Israeli Historians".

The conventional Zionist account of the 1948 War goes roughly as follows. The conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine came to a head following the passage, on 29 November 1947, of the United Nations partition resolution which called for the establishment of two states, one Jewish and one Arab. . . . [H]undreds of thousands of Palestinians fled to the neighbouring Arab states, mainly in response to orders from their leaders and despite Jewish pleas to stay and demonstrate that peaceful co-existence was possible. . . . For many years the standard Zionist account of the causes, character, and course of the Arab-Israeli conflict remained largely unchallenged outside the Arab world. The fortieth anniversary of the establishment of the State of Israel, however, was accompanied by the publication of four books by Israeli scholars who challenged the traditional historiography of the birth of the State of Israel and the first Arab-Israeli war. . .

- Morris 2004, p. 430.

- Also see Morris 1986, p. 92.

- Gelber 2006, pp. 161–162, also says the residents were already on their way out when this order was given.

- Morris 2004, p. 429.

- That the Ramle residents were supplied buses by the Kiryati brigade, see Morris 1988.

- Morris 2004, p. 431.

- Morris 1986, pp. 93–4. Morris finds Guttman's account subjective and impressionistic (p. 94, footnote 39). Guttman later wrote about Lydda under the pseudonym "Avi-Yiftah".

- Morris 2004, p. 432.

- Morris 2004, p. 455, footnote 96.

- Morris 2004, p. 432: At 18:15 hours that day, Dani HQ asked Yiftah Brigade: "Has the removal of the population [hotza'at ha'ochlosiah] of Lydda been completed?"

- Glubb 1957, plate 8, between pp. 159 and 161. The caption says: "Arab refugee women and children from Lydda and Ramle, resting after their arrival in the Arab area."

- Morris 1986, pp. 93–4; see p. 97 for the temperature.

- Morris 2004, pp. 433–4.

- Saleh Abd al-Jawad (2007). "Zionist Massacres: the Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem in the 1948 War". In Eyal Benvenisti; Chaim Gans; Sari Hanafi (eds.). Israel and the Palestinian Refugees. Springer. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-3540681601.

- Morris 2008, p. 291.

- Morris 2003, p. 177.

- Khalidi, page=80–98.

- Pappé 2006, p. 168.

- Morris 1986, p. 97.

- Brandabur 1990 Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Habash said: "The Israelis were rounding everyone up and searching us. People were driven from every quarter and subjected to complete and rough body searches. You can't imagine the savagery with which people were treated. Everything was taken—watches, jewellery, wedding rings, wallets, gold. One young neighbor of ours, a man in his late twenties, not more, Amin Hanhan, had secreted some money in his shirt to care for his family on the journey. The soldier who searched him demanded that he surrender the money and he resisted. He was shot dead in front of us. One of his sisters, a young married woman, also a neighbor of our family, was present: she saw her brother shot dead before her eyes. She was so shocked that, as we made our way toward Birzeit, she died of shock, exposure, and lack of water on the way."

- Morris 1986, p. 88.

- Segev 1986, pp. 69–71

- Morris 2004, p. 454, footnote 86.

- Ben-Gurion, Volume 2, p. 589.

- Kenan 1989; courtesy link Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- Morris 1986, p. 105.

- See also Segev 1986, pp. 71–72.

- For a discussion of Ben-Gurion's concern, see Tal 2004, p. 311.

- Cohen 2008, p. 139.

- Shipler, The New York Times, 23 October 1979. Rabin wrote: "Great suffering was inflicted upon the men taking part in the eviction action. Soldiers of the Yiftach brigade included youth movement graduates, who had been inculcated with values such as international fraternity and humaneness. The eviction action went beyond the concepts they were used to. There were some fellows who refused to take part in the expulsion action. Prolonged propaganda activities were required after the action, to remove the bitterness of these youth movement groups, and explain why we were obliged to undertake such harsh and cruel action."

- IDF Intelligence Service/Arab Department, 21 July 1948, cited in Morris 2008, p. 291.

- Morris 2008, pp. 290–291.

- Kirkbride 1976, p. 48, cited in Morris 2008, p. 291.

- Morris 2008, pp. 291–292.

- For Perie-Gordon, see Abu Nowar 2002, p. 208.

- Morris 2008, p. 295.

- Morris 2008, p. 309ff.

- Sayigh 2007, p. 84.

- "Bernadotte Murder Stuns Whole World", Ottawa Citizen, 18 September 1948.

- Pappe, Ilan (1992). The Making of the Arab–Israeli Conflict 1947–1951. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-819-9.Chapter 9: The Lausanne Conference.

- Palumbo, Michael (1987). The Palestinian Catastrophe. Quartet Books. pp. 184–189. ISBN 0 7043 0099 0.

- For "not one inhabitant," and the hundreds remaining, see Morris 2004, p. 434.

- For the numbers in October 1948, see Morris 2004, p. 455, footnote 110.

- For military rule ending, see Yacobi 2009, p. 39.

- Yacobi 2009, p. 42.

- Morris 2008, p. 308, for a general discussion of the issue.

- Yacobi 2009, p. 45, for specific mention of this in relation to Lydda.

- For the figures, and that most were from Asia and North Africa, see Golan 2003.

- Also see Yacobi 2009, p. 39.

- Yacobi 2009, p. 33.

- Yacobi 2009, p. 34.

- Yacobi 2009, pp. 35–36.

- Ankori 2006, pp. 48–50.

- For the image on Shammout's website: "Where to ..?", shammout.com. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- For the atrocities in general, see Morris 2004, p. 486ff; for reference to the poem and Ben-Gurion writing to Alterman, see p. 489.

- Morris writes that the poem is about Lydda in Morris 2004, pp. 426, 489 (on p. 489 he writes it was "apparently" about Lydda), and Morris 2008, p. 473, footnote 85.

- Cohen 2008, p. 140

- Jewish Agency for Israel."Allon, Yigal (1918–1980)". Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- As'ad Abu Khalil 2005, p. 529ff.

- Andrews and Kifner, The New York Times, January 27, 2008.