Raj of Sarawak

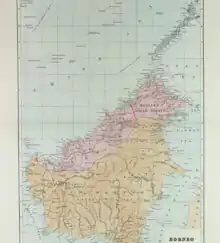

The Raj of Sarawak, also State of Sarawak, located in the northwestern part of the island of Borneo, was an independent state that later became a British protectorate. It was established as an independent state from a series of land concessions acquired by an Englishman, James Brooke, from the sultan of Brunei. Sarawak received recognition as an independent state from the United States in 1850, and from the United Kingdom in 1864.

Raj of Sarawak Kerajaan Sarawak | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1841–1941 1945–1946 | |||||||||||||||

Anthem: | |||||||||||||||

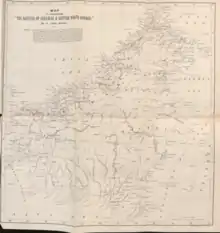

The Raj in the 1920s | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Independent state (until 1888) Protectorate of the United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kuching | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English, Iban, Melanau, Bidayuh, Sarawak Malay, Chinese etc. | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy,[3][4] Protectorate | ||||||||||||||

| White Rajah | |||||||||||||||

• 1841–1868 (first) | James Brooke | ||||||||||||||

• 1917–1946 (last) | Charles Vyner Brooke | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Council Negri | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 24 September 1841 | ||||||||||||||

• Protectorate | 14 June 1888 | ||||||||||||||

| 16 December 1941 | |||||||||||||||

| 10 June 1945 | |||||||||||||||

• Ceded to the Crown colony | 1 July 1946 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1945 | 124,450 km2 (48,050 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1841 | 8,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1848 | 150,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1893 | 300,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1933 | 475,000 | ||||||||||||||

• 1945 | 600,000 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Sarawak dollar | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

Following recognition, Brooke expanded the Raj's territory at the expense of Brunei. Several major rebellions occurred against his rule, causing him to be plagued by debt incurred in countering the rebellions, and the sluggish economic situation at the time. His nephew, Charles Brooke, succeeded James and normalised the situation by improving the economy, reducing government debts and establishing public infrastructure. In 1888, the Raj acquired protectorate status from the British Government which avoiding annexation.

To gear up economic growth, the second Rajah encouraged the migration of Chinese workers from China and Singapore to work in the agricultural fields. With proper economic planning and stability, Sarawak prospered and emerged as one of the world's major producers of black pepper, in addition to oil and the introduction of rubber plantations. He was succeeded by his son Charles Vyner Brooke but World War II and the arrival of Japanese forces ultimately brought an end to the Raj and the Protectorate administration, with the territory placed under a military administration on the Japanese capitulation in 1945, and ceded to Britain as its last acquisition as Crown Colony in 1946, against the Atlantic Charter. The area now forms the Malaysian state of Sarawak.

History

Foundation and early years

_by_Francis_Grant.jpg.webp)

The raj was founded by James Brooke, an English adventurer who arrived to the banks of Sarawak River and decided to berth his schooner there in 1839.[5] After serving in the First Anglo-Burmese War where he was severely wounded in battle,[6][7] Brooke returned to England in 1825 to recover from his injury. Despite his attempts to return into service, he was unable to return to his station in India before his temporary leave from the service expired.[8] Overstaying his furlough resulting in his position in the military being forfeited, but he was awarded a pension by the government for his service.[8][9][10] He continued on from India and went to China to improve his health.[11]

On his way to China in 1830, he saw the islands of the Asiatic Archipelago, still generally unknown to Europeans.[11] He returned to England and made an abortive trading journey to China in the Findlay before his father died in 1835.[12][13] Inspired by the adventure stories regarding the success of the East India Company (EIC) where his father had been serving especially from the efforts of Stamford Raffles to expanding the company influence in the Asiatic Archipelago,[14][15][16] he purchased a schooner named Royalist using the £30,000 left to him by his father.[6][7] He recruited a crew for the schooner, training in the Mediterranean Sea in late 1836,[8] before beginning their sail to the Far East on 27 October 1838.[12] By July 1839, he reached Singapore and came across some British sailors who had been shipwrecked and helped by Pengiran Raja Muda Hashim, the uncle of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II of Brunei.[8][17]

Brooke originally planned to sail to Marudu Bay in northwestern Borneo, but the British Governor-General in Singapore asked him to thank Raja Muda Hashim in southwestern Borneo.[8][18][19] The following month he sailed to the western coast of the island and on 14 August 1839, berthed his schooner on the banks of the Sarawak River and met Hashim to deliver the message.[18] The Raja told Brooke that his presence in the area was to control a rebellion against the Sultanate of Brunei caused by the oppressive policies of Pengiran Indera Mahkota, a kinsman of the Sultan.[17][20][21] Mahkota had earlier been dispatched by the Sultan to monopolise the antimony in the area; which as a result directly affecting the incomes of the local Malays there and growing frustration from the indigenous Land Dayak who had been forced to work in the mines for about 10 years.[22][23] It has also been alleged that the rebellion against Brunei was aided by the neighbouring Sultanate of Sambas and the government of the Dutch East Indies, who wanted to establish economic rights over the antimony.[24] Despite Hashim's efforts to stop the rebellion, it came to no avail thus leading him to seek direct help from Brooke.[19]

Responding to the request, a force of local natives that was raised and led by Brooke managed to temporarily stop the rebellion.[21] Brooke was granted a large quantity of antimony from the local mines and authority in the Sarawak River area as a reward.[19] After that, Brooke became embroiled in Hashim's campaign to restore order in the area.[25] Brooke returned to Singapore and spent another six months cruising along the coasts of the Celebes Islands before returning to Sarawak on 29 August 1840.[12][26]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Malaysia |

|

|

|

Establishment

Upon his returning to Sarawak, the rebellion against Brunei's rule was still in progress. He managed to completely suppress the rebellion and pardoned the rebels for joining his side, providing positions in some administrative authority while limiting their power.[29] Despite the initial refusal of Hashim to pardon them and wanting to execute all the rebels, Hashim was convinced by Brooke to forgive them as he had taken the major part in their suppression.[30] In exchange for Brooke's continuous support towards the Sultanate and rental payment of £500, he was awarded the Kuching area from the Sultanate of Brunei;[25][31] which later became Sarawak First Division.[32] Hashim, however, began to think twice about giving the territory to Brooke, a doubt fanned by Mahkota who had been deprived of his power in the area in favour of Brooke.[26] This led Hashim to constantly delay the recognition of concession and angered Brooke. Brooke, with Royalist fully armed, went ashore to Hashim's audience chamber and called on him to negotiate. With little choice, and putting the blame mainly on Mahkota, Hashim granted Sarawak to Brooke on 24 September 1841.[33] Brooke issued new laws for the territory banning slavery, headhunting and piracy;[34] and by July 1842, his appointment was confirmed by Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II.[26]

.svg.png.webp)

.JPG.webp)

To prevent any further dispute with Brunei, Brooke hoped to reform the administration of the Sultanate and establish a pro-British government through Hashim and his brother Pengiran Badruddin. By October 1843, Brooke returned the two brothers to Brunei, bringing along Admiral Edward Belcher of the Royal Navy in HMS Samarang and the EIC Phlegethon.[35] The vessels anchored at the Sultan's audience chamber, requesting Pengiran Yusof's position as Bendahara to be replaced by Hashim and asking the Sultan to pledge to suppress piracy in his dominions, as well ceding the island of Labuan to the British (although the British government had not asked for this).[35] The status of Brooke as a Rajah and consul for the British at the time also remained controversial in the United Kingdom as he was not recognised by the British government to represent the British subjects.[36][37] Indirectly, Brooke had become involved in an internal dynastic dispute of Brunei.[38] From 1844, Brooke actively assisted the suppression of piracy on the coasts of western and northern Borneo together with Admiral Henry Keppel in HMS Dido along with Phlegethon;[39] where during the course of piracy suppression they encountered Mahkota, the former administrator of Kuching area who had formed an alliance with a Sea Dayak pirate chief on the Skrang River in Sarawak and captured him in the same year.[40][41]

In August 1845, Admiral Thomas Cochrane arrived at Brunei with a squadron of from six to eight ships to release two Lascar seamen who were believed to be hidden there.[38][42] Badruddin accused Yusof of being involved in the slave trade due to his close relations with a notable pirate leader Sharif Usman in Marudu Bay and the Sultanate of Sulu.[38] Denying the allegation, Yusof refused to attend a meeting with Cochrane, and escaped after being threatened with force by Cochrane before regaining his own force in the Brunei capital. Cochrane then sailed away to Marudu Bay in pursuit of Usman, while Yusof was defeated by Badruddin.[38][42] Hashim managed to establish a rightful position in Brunei Town to become the next Sultan after successfully defeating the piratical forces led by Yusof who fled to Kimanis in northern Borneo where he was executed.[43][44] Yusof was the favourite noble to the Sultan and with Hashim's victory, this upset the chances of the son of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II to become the next leader.[44][45] Mahkota, who had returned to Brunei in 1845 after his capture in Sarawak in 1844 became the Sultan's adviser in the absence of Yusof who had been executed. He prevailed on the Sultan to order the execution of Hashim,[42] whose presence had become unwelcome to the royal family, especially due to his close ties with Brooke that were favourable to English policy.[46] Beside that, an adventurer named Haji Saman, who was connected to the late Yusof, played upon the Sultan's fear of Hashim taking over his throne.[47]

By the order of the Sultan, Hashim and his brother Badruddin together with their family were assassinated in 1846.[42][46][48] One of Badruddin's slaves, Japar, survived the attack and intercepted HMS Hazard, which brought him to Sarawak to inform Brooke. Enraged by the news, Brooke organised an expedition to avenge Hashim's death with the aid of Cochrane from the Royal Navy with Phlegethon.[47] On 6 July 1846, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II complained through a letter about the discourtesy of HMS Hazard and invited Cochrane to ascend the capital with two boats. Phlegethon and other vessels then moved up to the river on 8 July where they were fired on from every position with slight damage.[47] Mahkota and the Sultan retreated upriver while most of the population fled upon their arrival at Brunei's capital, leaving the brother of the Sultan's son, Pengiran Muhammad, who was badly wounded and Pengiran Mumin, an opponent of the Sultan's son who despised the decision of his royal family to be involved in conflict with the British.[42][47] The British destroyed the town forts and invited the population to return with no harm to be done to them while the Sultan remained hiding in the jungle. Another expedition was sent to the interior but also failed to find the Sultan. Brooke remained in Brunei with Admiral Rodney Mundy and HMS Iris along with Phlegethon and HMS Hazard while the main expedition continued their mission to suppress piracy in northern Borneo.[47]

Upon finding that Haji Saman was living in Kimanis and that he was involved in the plotting that caused Hashim's death, Brooke departed there and destroyed his house although Saman still managed to escape.[47] Brooke returned again to Brunei and finally managed to induce the Sultan to return to the capital where the Sultan finally regretted the killings of Hashim, his brother and their family members by writing a letter of apology to Queen Victoria.[49] Through his confession, the Sultan recognised Brooke's authority over Sarawak and mining rights throughout the territory without requiring him to pay any tribute as well granting the island of Labuan to the British.[49] Brooke departed Brunei and left Mumin in charge together with Mundy to keep the Sultan in line until the British government made a final decision to acquire the island. Following the ratification agreement of the transfer of Labuan to the British, the Sultan also finally agreed to allow British forces to suppress all piracy along the coast of Borneo.[49]

Later years

.svg.png.webp)

The following year, 1847, Brooke asked the Sultan of Brunei to sign another treaty to prevent the Sultanate from engaging in any concession treaty with other foreign powers especially after the visit of USS Constitution in 1845.[49] American policy at the time however made no intention to establish any solid presence in Asia and the Pacific.[50] By 1850, the United States recognised the status of Brooke's raj as an independent state.[51] Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II died in 1852 and he was succeeded by Mumin, which already proved a success in Brooke's efforts to establish a pro-British government in Brunei.[52] The new Sultan then ceded Saribas and Skrang districts, which later became the Second Division, to Brooke in 1853 due to conflict with pirates.[32][53]

Three major rebellions led by Rentap (1853),[54] Liu Shan Bang (1857)[55][56] and Syarif Masahor (1860)[57] shook the Rajah's administration which, together with the stagnant economic conditions at the time, caused Brooke to be plagued by debt.[58] He was driven into planning to cede Sarawak to the British to settle his debt; while the idea was supported by some of Britain's members of parliament (MPs) and businessmen, it was rejected by Prime Minister Lord Derby who feared that the introduction of a British taxation system would shock the population more than exercising their own system under the Rajahs.[59] There were also concerns about its financial viability and probable drain on the exchequer.[60] Brooke then thought to sell his kingdom to Belgium, France, Russia or to Brunei again or also to other European powers rather than to the neighbouring Dutch who were ready to retake Sarawak.[59] Brooke's intention had already been decried by neighbouring British governors such as Labuan Governor Hennessy who, while respecting the Rajah, considered Sarawak a mere vassal state of Brunei.[61]

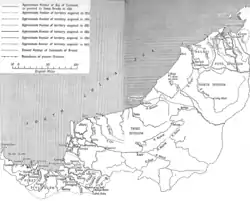

Prior to the ongoing piracy suppression, a major battle with the Illanuns of Moro pirates from the southern Philippines occurred in mid-November 1862.[62] In 1864, the United Kingdom appointed a Consul to Sarawak and recognised the raj,[51][63] while the Netherlands refused recognition.[64] Brooke then expanded his raj into territory of Brunei.[65] In 1861, he acquired the vast Rajang River basin, which subsequently became the Third Division.[32][53] The expansion continued after his death in 1868; when he was succeeded by his nephew, Charles Brooke.[66][67]

Under Charles' administration, Sarawak's economy grew rapidly, especially later on with the discovery of oil, introduction of rubber, and the construction of public infrastructure as his main priorities to stabilise the economic situation and reduce government debts.[68][69][70] He encouraged the migration of Chinese to boost the economy, especially in agricultural sectors;[71][72] where most of them settled around Kuching (mainly Hokkien and Teochew), Sibu (mainly Fuzhou) and Sri Aman (mainly Teochew).[73][74] Charles was trusted and respected for his fairness and strict order, although he was not so popular among the local Malays as his uncle, while being a close friend to the Dayaks.[75] Sarawak prospered under his rule and he did not seek protection from any European powers although requests for protection from the British in 1869 and 1879 were rejected.[75] Charles continued to seek protection from the British, securing Protectorate status from them on 14 June 1888.[76][75] He ruled Sarawak until his death in 1917 and was succeeded by his son, Charles Vyner Brooke.[77]

World War II and decline

Following World War I, the Empire of Japan began to expand their range in Asia and the Pacific.[78] Vyner became aware of the growing threats and began to institute reforms.[79] Under the protectorate treaty, Britain was responsible for Sarawak's defence[80] but it could do little, most of its forces having been deployed to the war in Europe against Nazi Germany and the Kingdom of Italy. The defence of Sarawak depended on a single Indian infantry regiment, the 2/15 Punjab Regiment, together with the local forces of Sarawak and Brunei.[80] As Sarawak had a significant number of oil refineries in Miri and Lutong, the British feared that these supplies would fall to the Japanese and thus instructed the infantry to carry out a scorched earth policy.[80][81]

On 16 December 1941, a Japanese navy detachment on Japanese destroyer Sagiri arrived at Miri from Cam Ranh Bay of French Indochina.[81][82] The Japanese then launched an air attack on Kuching on 19 December, bombing parts of the town airfield while machine-gunning people in the town streets.[83] The attack created panic and drove residents to the rural areas.[84] The Dutch submarine HNLMS K XVI managed to bring down the Japanese from Miri but, with the arrival of the Japanese destroyer Shirakumo together with other ships, the Japanese secured the town on 24 December.[85] From 7 January 1942, Japanese troops in Sarawak crossed the border of Dutch Borneo and proceeded to neighbouring North Borneo. The 2/15 Punjab Regiment were forced to withdraw to Dutch Borneo and later surrendered on 9 March after most of the Allies had surrendered in Java.[83] A steamship of Sarawak, the SS Vyner Brooke, was sunk while evacuating nurses and wounded servicemen in the aftermath of the fall of Singapore. Most of its surviving crew were massacred on Bangka Island.[86]

.JPG.webp)

Lacking air protection, Sarawak, together with rest of the island, fell to the Japanese and Vyner took sanctuary in Australia.[87] Many of the British and Australian soldiers captured after the fall of Malaya and Singapore were brought to Borneo and held as prisoners of war (POWs) in Batu Lintang camp in Sarawak and Sandakan camp in neighbouring North Borneo. The Japanese military authorities placed the southern part of Borneo under the navy, while its army were responsible for management of the north.[88] As part of the Allied Campaign to retake their possessions in the East, Allied forces were then sent to Borneo in the Borneo Campaign and liberated the island. The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) played a significant role in the mission. The Allies' Z Special Unit provided intelligence gathering which facilitated the AIF landings. Most of the major towns of Sarawak were bombed during this period.[84] The war ended on 15 August 1945 following the Japanese surrender and the administration of Sarawak was undertaken by the British Military Administration (BMA) from September. Vyner returned to administer Sarawak but decided to cede it to the British government as a Crown Colony on 1 July 1946 due to lack of resources to finance reconstruction.[89][90][91]

Government

_01.jpg.webp)

Prior to the establishment of the Sarawak Administrative Service under the second Rajah, there had been no formal civil administration.[92] The civil service recruited Europeans, mainly British officers, to run district outstations where the residents became exposed to and trained in many British and European methods and culture, while retaining the customs of the indigenous people. After the acquisition of more territory, Sarawak was divided into five divisions, each headed by a Resident.[93] The Rajahs also encouraged the establishment of schools, healthcare services and transport.[94]

The government worked to restore peace where piracy and tribal feuds had grown rampant and its success depended ultimately on the co-operation of the native village headmen, while the Native Officers acted as a bridge.[95] The Sarawak Rangers was established in 1862 as a para-military force of the raj.[96] It was superseded by the Sarawak Constabulary in 1932 as a police force,[97] with 900 members mainly comprising Dayaks and Malays.[98]

As a British protectorate, all powers of governance were conducted under the purview of the British government although constitutionally remaining an independent state ruled by the Rajahs.[76] According to an agreement signed on 14 June 1888,[76] it was stipulated:

I. The State of Sarawak shall continue to be governed and administered by the said Rajah and his successors as an independent State under the protection of Great Britain; but such protection shall confer no right on Her Majesty's Government to interfere with the internal administration of the State further than is herein provided.

II. In case any question should hereafter arise respecting the rights of succession to the present or any future Ruler of Sarawak, such question shall be referred to Her Majesty's Government for decision.

III. The relations between the State of Sarawak and all foreign States, including the States of Brunei and North Borneo, shall be conducted by Her Majesty's Government, or in accordance with its directions; and if any difference should arise between the Government of Sarawak and that of any other State, the Government of Sarawak agrees to abide by the decision of Her Majesty's Government, and to take all steps necessary to give effect thereto.

IV. Her Majesty's Government shall have the right to establish British Consular officers in any part of the State of Sarawak, who shall receive exequaturs in the name of the Government of Sarawak. They shall enjoy whatever privileges are usually granted to the Consular officers, and shall be entitled to hoist the British flag over their residences and public offices.

V. British subjects, commerce, and shipping shall enjoy the same right, privileges, and advantages as the subjects, commerce, and shipping of the most favoured nation, as well as any other rights, privileges, and advantages which may be enjoyed by the subjects, commerce and shipping of the State of Sarawak.

VI. No cession or other alienation of any part of the territory of the State of Sarawak shall be made by the Rajah or his successors to any foreign State, or the subjects or the citizens thereof, without the consent of Her Majesty's Government; but this restriction shall not apply to ordinary grants or leases of lands or houses to private individuals for purposes of residence, agriculture, commerce, or other business.

Economy

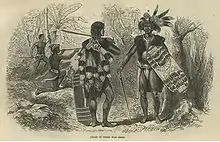

Upon acquisition of his first territories in the First Division, Brooke came into possession of a large quantity of antimony from mines around the area.[99] At the time of his arrival, a land tenure system known as the Native Customary Rights (NCR) had been practised by the indigenous communities.[100][101][102] Brooke's first priority was to abolish headhunting among the indigenous communities of the interior. The kingdom's authorities conducted repeated raids on Sea Dayak villages and, facing a major rebellion, ultimately forced them to practice horticulture and abandon headhunting.[103][104] Land Dayaks had also been involved in headhunting but more readily abandoned the practice[105] and became loyal followers of Brooke.[27][28] Most Malay coastal villages were also raided as part of the kingdom's policy to combat piracy and slavery.[103] Despite success in these endeavours, stagnant economic conditions persisted and the kingdom amassed huge debts.[58]

Brooke promoted Chinese immigration, convinced that they would inject vigour into the economy and prove an encouragement to indigenous communities to participate.[106] Initially, most of the immigrants were miners originating from Sambas in neighbouring Dutch Borneo. These later formed a Kongsi system in Bau.[107] The second Rajah continued this policy, particularly targeting the agricultural sector.[71][72] Conflicts ensued between the government and the Chinese in 1857, believed to have arisen, inter alia, in relation to the Second Opium War.[108][109]

Borneo Company Limited was formed in 1856. It was involved in a wide range of businesses in Sarawak, including trade, banking, agriculture, mineral exploration and development.[110] The second Rajah worked to stabilise the economy and reduce government debt. The economy grew significantly under his reign, with total exports reaching $386,439 and imports $414,756 in 1863.[75]

In 1869, by which time total trade had reached $3,262,500,[75] the second Rajah invited Chinese black pepper and gambier growers from Singapore to cultivate their crops in Sarawak.[111][112] As a result, by the early 20th century, Sarawak became one of the world's major producers of pepper.[113] The kingdom was a relative latecomer to the natural rubber boom due to the reluctance of the second Rajah to give over indigenous farmland to European companies.[114] Only five large rubber estates were established during his reign.[107] Oil reserves were discovered in his final years.[115] From the 1930s, through the work of the Chinese businesses in the kingdom, it became a significant raw material supplier, with Singapore a major trading partner.[98][116]

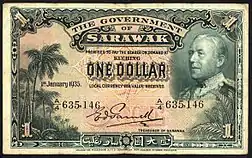

Currency

A Sarawak dollar was first issued in 1858 and remained at par with the Straits dollar. Different notes were issued by the Sarawak Government Treasury, the earliest notes using English, Jawi and Chinese characters. From the 1880s, the notes' background featured the Rajah's portrait and coat of arms.[117]

Society

Demography

In 1841, Sarawak had an indigenous population of about 8,000.[65] The Dayaks were the largest indigenous group in the interior: comprising Iban, Bidayuh and other interior tribes such as the Kayan, Kelabit, Kenyah, Lun Bawang and Penan, while coastal areas were dominated by the Sarawak local Malays, Melanau, Bruneian and Kedayan.[98] The government of Sarawak welcomed the migration of Chinese workers to boost the economy.[71][72] Following various immigration schemes initiated by the Rajahs, the population increased to 150,000 in 1848,[118] 300,000 in 1893,[119] 475,000 in 1933,[98] and 600,000 in 1945.[65]

Water transport

It was during the reign of the Second Rajah that public infrastructure began to be given attention.[120] The river systems in Sarawak are not inter-connected. As a result, coastal ships were used by the Brooke government to carry merchandise from one river system to another. The Brooke government also established a trade route from Kuching to Singapore, using its own ships such as The Royalist, Julia, and The Swift. Among the early cargoes were antimony and gold. The Borneo Company Limited bought another steamer, which they named the Sir James Brooke, to carry antimony, coal, and sago. The ships were the link between Sarawak and Singapore. Charles Brooke encouraged the Sarawak Chamber of Commerce to set up its own shipping lane to Singapore, offering to sell The Royalist to it. In 1875, the "Singapore and Sarawak Steamship Company" was formed and, shortly thereafter, bought The Royalist and the steamer The Rajah Brooke. There were complaints that the company provided irregular services to its customers and, in 1908, the Brooke government transferred another two small steamships, the Adeh and Kaka, to the company in expectation of improvement. In 1919, Chinese interests bought the company's shares, liquidated it and formed a new company named the "Sarawak Steamship Company". The company established shipping lanes linking the Rajang, Limbang, and Baram river systems. The Sibu-Singapore shipping lane was started by the company but soon abandoned, being unprofitable. The establishment of the shipping lanes by Sarawak Steamship Company allowed the indigenous people to participate in wider markets, thus narrowing the income gap between urban and rural areas in Sarawak.[121] The company suffered heavy losses in the trade depression of the 1920s and was acquired by the Singapore-based "Straits Steamship Company". The company established branches at Sibu and Bintulu and installed agents at other small river ports.[121]

Land transport

Land transport in Sarawak was poorly developed owing to the swampy environment around rivers downstream, while dense jungles presented significant challenges to road construction inland. Most of the roads were constructed in coastal areas. Borneo Company Limited and Sarawak Oilfields also constructed a small number of short roads to serve their own economic interests. Meanwhile, in the interior, raised batang paths were made by the natives using logs to connect villages and their environs, easing access to farms and collection of forest produce. At the same time, rivers remained the most important means of transportation to coastal towns. In the first 70 years of Brooke rule, bridle paths were constructed to connect administrative posts to the surrounding districts. After the 1930s, the policy was changed to providing access from villages to navigable rivers. Road construction during the Brooke era was, however, uncoordinated. Most of the roads located near the towns were short, with the exception of the economically important Miri-Lutong road built by Sarawak Oilfields, the Jambusan road to Tegora via the Dahan estate, and Penrissen road built by the Brooke government. Together with the road developments, bullock carts were introduced together with porters, and hand carts in the mid-19th century, followed by rickshaws at the end of the 19th century, and bicycles in the early 20th century. Public motor services appeared in 1912 together with private taxis.[123] In 1915, a short railway connecting Kuching to Tenth Mile was opened to the public. Subsequent construction of a road running parallel to the railway led to substantial losses, however, and its operations were limited to transportation of rocks from Seventh Mile to Kuching.[123][124][125]

Electricity and communication

In 1894, while plans for electric street lightning were being drawn up in Penang and Kuala Lumpur on the Malay peninsula, Rajah Charles Brooke refused to adopt this new technology because of his dislike of "new-fangled things". The sparse population of Sarawak also presented a logistical challenge to install power stations and connecting cables.[126] However, wired telephones were installed around Kuching in 1898 for keeping up to date communications with the outstations. Otherwise, messages from the northernmost areas of the state such as Limbang and Baram could take up to a month to reach Kuching. Besides, telephones were cheap to install and required little power. By 1908, the Mukah-Oya region was connected to telephone lines, followed by Miri in 1913, and Sibu in 1914.[127] The first wireless telegraphy station was erected in Kuching in 1917, followed by Sibu and Miri immediately thereafter.[128] It was not until 1914 that the first electrical power stations were installed in Miri by Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company and Bau by the Borneo Company Limited. The oil production boom in Miri and gold mining in Bau gave rise to the need of more efficient lightning and motor systems. Cinematography also began the same year in Miri.[129] In 1920, J.R Barnes, the manager of the Sarawak Government Wireless Telegraphs and Telephones Department, proposed an electrical lightning scheme for Kuching using a coal-fired system. In January 1923, a power station covering an area of 6,700 square feet (620 m2) was completed at Khoo Hun Yeang Street, Kuching, and started operation in June 1923, supplying Kuching with direct current (DC) system.[130] Today the road where the power station was once located is now known as the "Power Street".[131][132] Sibu's first power station was installed in 1927, followed by Mukah in 1929.[133] From 1922 to 1932, the electrical supply in Kuching was managed by the Electrical Department, under the jurisdiction of Public Works Department. This department was then privatised as the Sarawak Electricity Supply Company (SESCo).[134] From the 1930s, a telegraph line connected the country with Singapore.[135] Wireless telegraph stations were located in all major towns in Sarawak.[98] Postal service was also available throughout the administration.[136]

Health

In 1915, Dr Ledingham Christie, surgeon to the Borneo Company Limited, conducted a study regarding latent dysentery and parasitism amongst the Malay population staying near the Sarawak River. Those who had latent dysentery or parasites may no show any symptoms, but their built-up may be pale and thin. The Malays at that time usually dump their sewage into the river, while taking bath or drink from the same spot; in anticipation that water currents will bring the waste away. Among the 100 stool samples tested, whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) and roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides) were most commonly found.[137] Cholera was endemic in Sarawak, however very little is documented about the disease. The earliest cholera outbreak in Sarawak was in 1873 but it was not known how many have died. In the same year, Captain Giles Helyer, the commander of the boat "Heartsease" died of cholera. Meanwhile, the two children of Rajah James Brooke also died on board the ship "S.S. Hydaspes", possibly due to cholera. In 1888, an outbreak occurred amongst a number of Malays in Simanggang District. In 1902, another cholera pandemic occurred with 1,500 deaths. It was an expeditionary force organised by the Brookes to punish the Dayaks living in the rural areas of the Simanggang District. This was because the Dayaks were killing and attacking friendly neighbours. The epidemic caused the break-up of the expeditionary force without achieving any of its military objectives. There were also outbreaks in 1910 and 1911. Nevertheless, no outbreaks were reported from 1911 to 1941.[138]

The first doctor was appointed shortly after James Brooke was proclaimed the Rajah.[139] Kuching Hospital services existed in the 1800s but no records were available. The earliest record of the Kuching hospital (now Sarawak General Hospital) was available in 1910 where it was admitting 920 patients that year.[140] In 1925, a leprosy settlement was constructed in Kuching. Rajah Charles Brooke Memorial Hospital was also constructed to treat leprosy patients.[141] In 1931, a facility to treat mental illness was constructed beside the Kuching Hospital.[141] In Sibu, the construction of Lau King Howe Hospital (now Lau King Howe Hospital Memorial Museum) was completed in 1936.[142] In 1935, there were six doctors serving the needs of the senior government servants. State Health Office (known as Medical Headquarters) was located at the Kuching Pavilion building from 1909 to 1947. There was only one assistant dental officer before the Japanese occupation. Charles Vyner Brooke had been persuading doctors from the Straits Settlements to serve in Sarawak but the response had been cold.[139] The medical service continued under the Japanese occupation. There are few records regarding the development of dentistry in the 1900s. Several accounts from the elderly people stated that there were traditional healers and roadside tooth-pullers performing palliative treatments at that time. The first government dentist was appointed in July 1925 at Kuching General Hospital. In 1932, "Sarawak Government Registration of Dentist Ordinance" was introduced. A total of 15 dentists were registered before the Japanese occupation.[143]

Science

In 1854, Alfred Russel Wallace arrived in Kuching as a guest of James Brooke. In 1855, he wrote a paper entitled "On the law which has regulated the introduction of new species", also known as the "Sarawak Law", which anticipated aspects of Darwin's theory of evolution.[144] It is said, albeit without any evidence, that Charles Brooke approved the construction of Sarawak State Museum in 1888, the oldest museum in Borneo, with endorsement from Wallace. [145] Charles Hose, who served under Brooke as an administrator in the Baram region, was an avid photographer, naturalist, ethnologist, and author. He is credited with the discovery of various mammal and bird species endemic to Borneo: some of his specimens are now housed in London's Natural History Museum (catalogue). His ethnological collections are in, amongst others, the British Museum.[146]

Media

The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (since 1820), the Sarawak Gazette (since 1870),[147] and the Sarawak Museum Journal (since 1911) hold a significant amount of information on Sarawak before and during the Rajahs administration.

See also

References

Citations

- Barley 2013, p. 101.

- Straumann 2014, p. 63.

- Storey 2012, p. 7.

- Great Britain. War Office 1942, p. 123.

- Pybus 1996, p. 9.

- Foggo 1853, p. 7.

- Hazis 2012, p. 66.

- Storey 2012, p. 6.

- Boyle 1868, p. 204.

- Fraser 2013, p. 133.

- anon 1846, p. 357.

- Boyle 1868, p. 205.

- anon 1836, p. 207.

- Reece 2004, p. 7.

- Runciman 2010, p. 45.

- Knapman 2016, p. 156.

- Eliot, Bickersteth & Ballard 1996, p. 555.

- Hilton & Tate 1966, p. 79.

- Ring, Watson & Schellinger 2012, p. 160.

- Miller 1970, p. 48.

- Leake 1989, p. 27.

- Chang 1995, p. 15.

- Walker 2002, p. 26.

- Walker 2002, p. 29.

- Webster 1998, p. 130.

- Saunders 2013, p. 74.

- anon 1862, p. 110.

- Morrison 1993, p. 11.

- Barbara Watson & Leonard Y. 2016, p. 134.

- anon 1879, p. 633.

- Wesseling 2015, p. 208.

- Lea 2001, p. 17.

- MacGregor 1896, p. 43.

- Baynes 1902, p. 307.

- Saunders 2013, p. 75.

- Knapman 2016, p. 197.

- Irwin 1955, p. 127.

- Saunders 2013, p. 76.

- Belcher & Adams 1848, p. 146.

- Bickersteth & Hinton 1996, p. 306.

- Talib 1999, p. 5.

- Gott 2011, p. 374.

- Miller 1970, p. 95.

- Royal Asiatic Society 1960, p. 292.

- Mills 1966, p. 258.

- Miller 1970, p. 94.

- Saunders 2013, p. 77.

- Sidhu 2016, p. 154.

- Saunders 2013, p. 78.

- Saunders 2013, p. 79.

- Great Britain. Colonial Office 1962, p. 300.

- Saunders 2013, p. 80.

- Wright 1988, p. 95.

- Cramb 2007, p. 116.

- Chang 1995, p. 45–47.

- Chin 1996, p. 23.

- Reece 2004, p. 35.

- Press 2017, p. 23.

- Press 2017, p. 24.

- Bowring 1859, p. 342.

- Wright 1988, p. 94.

- McDougall 1882.

- Madden, Fieldhouse & Darwin 1985, p. 556.

- Baring-Gould & Bampfylde 1909, p. 128.

- Purcell 1965, p. 58.

- Pybus 1996, p. 51.

- Sidhu 2016, p. 83.

- la Boda 1994, p. 498.

- Rowthorn, Cohen & Williams 2008, p. 25.

- Welman 2017, p. 176.

- Ledesma, Lewis & Savage 2003, p. 401.

- Cramb 2007, p. 124.

- Yong 1994, p. 35.

- Cotterell 2011, p. 135.

- Wright 1988, p. 85.

- Great Britain. Foreign Office 1888, p. 239.

- Olson & Shadle 1996, p. 200.

- Ooi 1999, p. 1.

- Shepley 2015, p. 46.

- Kratoska 2013, p. 136.

- Rottman 2002, p. 206.

- Williams 1999, p. 6.

- Tarling 2001, p. 91.

- Tan 2011.

- Jackson 2006, p. 440.

- Pateman 2017, p. 42.

- Bayly & Harper 2005, p. 217.

- Ooi 2013, p. 15.

- Yust 1947, p. 382.

- Lockard 2009, p. 102.

- Sarawak State Government 2014.

- Talib 1993, p. 6.

- Hock 2011.

- Aspalter 2017, p. 112.

- Talib 1999, p. 47.

- Tarling 2003, p. 319.

- Ellinwood Jr. & Enloe 1978, p. 201.

- Epstein 2016, p. 102.

- Brooke (3) 1853, p. 159.

- Cooke 2006, p. 46.

- Eguavoen & Laube 2010, p. 216.

- Uncle DI 2017.

- Tajuddin 2012, p. 35.

- Eliot, Bickersteth & Ballard 1996, p. 297.

- Ling 2013, p. 290.

- Brooke (1) 1853, p. 101.

- Bissonnette, Bernard & de Koninck 2011, p. 59.

- Baker 2008, p. 160.

- Ringgit 2015.

- Yeong Jia 2007.

- Bulbeck et al. 1998, p. 68.

- Cramb 2007, p. 128.

- Lockard 2009, p. 101.

- Ishikawa 2010, p. 72.

- Crisswell 1978, p. 216.

- Shiraishi 2009, p. 34.

- Cuhaj 2014, p. 1058.

- Whitaker 1848, p. 476.

- Appleton 1894, p. 396.

- Jackson 2007.

- Kaur 2016, p. 77–80.

- Ah Chon 1948, p. 48.

- Kaur 2016, p. 80–83.

- Durand & Curtis 2014, p. 175.

- Sarawak Government Railway 2015.

- Tate 1999, p. 9–10.

- Tate 1999, p. 15–17.

- Tate 1999, p. 20–21.

- Tate 1999, p. 30–31.

- Tate 1999, p. 30, 45, 48.

- Bakar 2011.

- Gazette 1922.

- Tate 1999, p. 61.

- Tate 1999, p. 49, 70.

- Kaplan & Roberts 1955, p. 115.

- Forrester-Wood 1959, p. 575.

- Ledingham Christie 1915, p. 89.

- Yadav 1990, p. 195-196.

- Sarawak Health 2012, p. 2.

- Sarawak Health 2012, p. 345.

- Sarawak Health 2012, p. 5.

- Sarawak Health 2012, p. 351.

- Sarawak Health 2012, p. 203.

- Rogers 2013.

- Tawie 2017.

- Lai 2016, p. 13.

- Sarawak Gazette 1870.

Sources

- anon (1836). Obituary – Thomas Brooke, Esg in The Gentleman's Magazine, Or Monthly Intelligencer. 41. William Pickering.

- anon (1846). Mr Brooke of Borneo in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. 59. William Blackwood.

- Belcher, Edward; Adams, Arthur (1848). Narrative of the Voyage of the H.M.S. Samarang, During the Years 1843–46: Employed Surveying the Islands of the Eastern Archipelago, Accompanied by a Brief Vocabulary of the Principal Languages ... Reeve, Benham, and Reeve.

- Whitaker, Joseph (1848). An Almanack for the Year of Our Lord ... J. Whitaker.

- Brooke (1), James (1853). The Private Letters of Sir James Brooke, K.C.B., Rajah of Sarawak, Narrating the Events of His Life, from 1838 to the Present Time. 1. R. Bentley.

- Brooke (3), James (1853). The Private Letters of Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak: Narrating the Events of His Life from 1838 to the Present Time. 3. R. Bentley.

- Foggo, George (1853). Adventures of Sir J. Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak. Effingham Wilson.

- Bowring, John (1859). A Visit to the Philippine Islands. Smith, Elder & Co.

- anon (1862). Mr. St. John's Borneo in The North British Review. 36–37. Leonard Scott [American Edition].

- Boyle, Frederick (1868). The Career and Character of Rajah Brooke in Temple Bar. 24. Richard Bentley.

- Sarawak Gazette (1870). "Sarawak Gazette". [Govt. Printer]. ISSN 0036-4762. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - anon (1879). St.John's Life of Sir James Brooke in Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. XLVIII.

- McDougall, Harriette (1882). "Sketches of Our Life at Sarawak (Illanun Pirates)". Project Canterbury, Anglican History.

- Great Britain. Foreign Office (1888). British and Foreign State Papers. H.M. Stationery Office.

- Appleton (1894). Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events. D. Appleton & Company [Data published in 1893].

- MacGregor, John (1896). Through the Buffer State: A Record of Recent Travels Through Borneo, Siam and Cambodia. F.V.White, London.

- Baynes, Thomas Spencer (1902). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: Latest Edition. A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and General Literature. Werner.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine; Bampfylde, Charles Agar (1909). A History of Sarawak Under Its Two White Rajahs, 1839–1908. H. Sotheran & Company.

- Gazette, Sarawak (1922). "The Singapore free press and merchatile advertiser". The Singapore free press and merchatile advertiser. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Great Britain. War Office (1942). Strategic survey of British North Borneo, Brunei and Sarawak: British Empire Section. May 8, 1942. Intelligence Division.

- Yust, Walter (1947). Ten eventful years: a record of events of the years preceding, including and following World War II, 1937 through 1946. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Ah Chon, Ho (1948). Kuching in pictures (1841-1946). Sarawak state library (Pustaka Negeri Sarawak).

- Irwin, Graham (1955). Nineteenth-century Borneo; a Study in Diplomatic Rivalry. M. Nijhoff.

- Kaplan, Irving; Roberts, Chester F. (1955). Area Handbook on British Borneo. University of Chicago for the Human Relations Area Files.

- Forrester-Wood, W. R. (1959). The Stamps and Postal History of Sarawak. Sarawak Specialists Society.

- Royal Asiatic Society (1960). Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 33. Royal Asiatic Society.

- Great Britain. Colonial Office (1962). Sarawak. H.M. Stationery Office.

- Purcell (1965). South East Asia Since 1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-06007-3.

- Mills, Lennox Algernon (1966). British Malaya, 1824–1867. Oxford University Press.

- Hilton, P. B.; Tate, Donna J. (1966). The modern world. Oxford University Press.

- Miller, Harry (1970). Pirates of the Far East. Hale. ISBN 9780709114291.

- Crisswell, Colin N. (1978). Rajah Charles Brooke: monarch of all he surveyed. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-580392-1.

- Ellinwood Jr., DeWitt C.; Enloe, Cynthia H. (1978). Ethnicity and the Military in Asia. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-2290-9.

- Madden, A. F.; Fieldhouse, David Kenneth; Darwin, John (1985). Select Documents on the Constitutional History of the British Empire and Commonwealth: "The Empire of the Bretaignes," 1175–1688. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-23897-0.

- Wright, Leigh R. (1988). The Origins of British Borneo. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-213-6.

- Leake, David (1989). Brunei: the modern Southeast-Asian Islamic sultanate. McFarland.

hashim.

- Morrison, Alastair (1993). Fair Land Sarawak: Some Recollections of an Expatriate Official. SEAP Publications. ISBN 978-0-87727-712-5.

- Talib, Naimah S. (1993). The Development of the Sarawak Administrative Service from Its Inception (1840s) to 1963 (PDF). University of Hull.

- Yong, Paul (1994). A dream of freedom: the early Sarawak Chinese. Pelanduk Publications. ISBN 978-967-978-377-3.

- la Boda, Sharon (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- Chang, Pat Foh (1995). The Land of Freedom Fighters. Ministry of Social Development, Sarawak.

- Pybus, Cassandra (1996). White Rajah: A Dynastic Intrigue. Univ. of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-2857-5.

- Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29366-5.

- Bickersteth, Jane; Hinton, Amanda (1996). Malaysia & Singapore Handbook. Footprint Handbooks. ISBN 978-0-8442-4909-4.

- Eliot, Joshua; Bickersteth, Jane; Ballard, Sebastian (1996). Indonesia, Malaysia & Singapore Handbook. Trade & Trade & Travel Publications ; New York, NY.

- Chin, Ung Ho (1996). Chinese Politics in Sarawak: A Study of the Sarawak United People's Party. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-983-56-0007-4.

- Webster, Anthony (1998). Gentleman Capitalists: British Imperialism in Southeast Asia 1770–1890. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-171-8.

- Bulbeck, David; Reid, Anthony; Cheng, Tan Lay; Yiqi, Wu (1998). Southeast Asian Exports Since the 14th Century: Cloves, Pepper, Coffee, and Sugar. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-3055-67-4.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (1999). Rising Sun over Borneo: The Japanese Occupation of Sarawak, 1941–1945. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-27300-3.

- Williams, Mary H. (1999). Special Studies, Chronology, 1941–1945. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-001876-3.

- Tate, Muzaffar (1999). The power behind the state (A history of Sarawak Electricity Supply Corporation (SESCO) and of Electricity Supply in Sarawak). Sarawak Electricity Supply Corp. ISBN 983-99360-1-8.

- Talib, Naimah S. (1999). Administrators and Their Service: The Sarawak Administrative Service Under the Brooke Rajahs and British Colonial Rule. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-983-56-0031-9.

- Lea; et al. (2001). A Political Chronology of South East Asia and Oceania. Europa Publications. ISBN 978-1-135-35659-0.

- Tarling, Nicholas (2001). A Sudden Rampage: The Japanese Occupation of Southeast Asia, 1941–1945. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-584-8.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

- Walker, John Henry (2002). Power and Prowess: The Origins of Brooke Kingship in Sarawak. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-711-5.

- Ledesma, Charles de; Lewis, Mark; Savage, Pauline (2003). Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-094-7.

- Tarling, Nicholas (2003). Imperialism in Southeast Asia. Routledge. ISBN 1-134-57081-3.

- Reece, Bob (2004). The White Rajahs of Sarawak: A Borneo Dynasty. Archipelago Press. ISBN 978-981-4155-11-3.

- Bayly, Christopher Alan; Harper, Timothy Norman (2005). Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941–1945. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01748-1.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-3760-0.

- Cooke, Fadzilah Majid (2006). State, Communities and Forests in Contemporary Borneo. ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-920942-52-6.

- Jackson, Caroline (2007). "Enlivening Brooke legacy". The Star. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017.

- Yeong Jia, Joshua Chia (2007). "The Borneo Company Limited". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 12 October 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- Cramb, Rob A. (2007). Land and Longhouse: Agrarian Transformation in the Uplands of Sarawak. NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-7694-010-2.

- Rowthorn, Chris (2008). Borneo. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-105-8.

- Baker, Jim (2008). Crossroads (2nd Edn): A Popular History of Malaysia and Singapore. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. ISBN 978-981-4435-48-2.

- Lockard, Craig (2009). Southeast Asia in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972196-2.

- Shiraishi, Takashi (2009). Across the Causeway: A Multi-dimensional Study of Malaysia-Singapore Relations. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-230-783-5.

- Eguavoen, Irit; Laube, Wolfram (2010). Negotiating Local Governance: Natural Resources Management at the Interface of Communities and the State. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-10673-5.

- Ishikawa, Noboru (2010). Between Frontiers: Nation and Identity in a Southeast Asian Borderland. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-476-0.

- Runciman, Steven (2010). The White Rajah: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12899-5.

- Cotterell, Arthur (2011). Western Power in Asia: Its Slow Rise and Swift Fall, 1415 – 1999. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-16999-5.

- Tan, Gabriel (2011). "Under the Nippon flag". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017.

- Bissonnette, Jean-Francois; Bernard, Stephane; de Koninck, Rodolphe (2011). Borneo Transformed: Agricultural Expansion on the Southeast Asian Frontier. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-544-6.

- Bakar, Lamah (2011). "The story behind the state's streets and roads". The Star (Malaysia). Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Hock, Lim Kian (2011). "A look at the civil administration of Sarawak". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017.

- Gott, Richard (2011). Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt. Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-84467-892-1.

- Tajuddin, Azlan (2012). Malaysia in the World Economy (1824–2011): Capitalism, Ethnic Divisions, and "Managed" Democracy. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-7196-7.

- Hazis, Faisal S. (2012). Domination and Contestation: Muslim Bumiputera Politics in Sarawak. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4311-58-8.

- Storey, Nicholas (2012). Great British Adventurers. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84468-130-3.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1.

- Rogers, Alan (2013). "Wallace and the Sarawak Law". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Ling, Alex (2013). Golden Dreams of Borneo. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4797-9168-2.

- Fraser, George MacDonald (2013). Flashman's Lady. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-63386-1.

- Saunders, Graham (2013). A History of Brunei. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-87394-2.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2013). Post-war Borneo, 1945–50: Nationalism, Empire and State-Building. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-05803-7.

- Barley, Nigel (2013). White Rajah: A Biography of Sir James Brooke. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-349-13985-2.

- Kratoska, Paul H. (2013). Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-12506-5.

- Durand, Frédéric; Curtis, Richard (2014). Maps of Malaysia and Borneo: Discovery, Statehood and Progress. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 978-967-10617-3-2.

- Cuhaj, George S. (2014). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues, 1368–1960. F+W Media, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4402-4267-0.

- Straumann, Lukas (2014). Money Logging: On the Trail of the Asian Timber Mafia. Schwabe AG. ISBN 978-3-905252-69-9.

- Sarawak State Government (2014). "Sarawak as a British Crown Colony (1946 â€" 1963)". Government of Sarawak. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017.

- Ringgit, Danielle Sendou (2015). "The Bau Rebellion: What sparked it all?". The Borneo Post Seeds. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017.

- Wesseling, H. L. (2015). The European Colonial Empires: 1815–1919. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-89507-7.

- Shepley, Nick (2015). Red Sun at War Part II: Allied Defeat in the Far East. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-78166-302-8.

- Sarawak Government Railway (2015). "Sarawak Government Railway". Malayan Railways.

- Kaur, A. (2016). Economic Change in East Malaysia: Sabah and Sarawak since 1850. Springer. ISBN 978-023-037-709-7.

- Barbara Watson, Andaya; Leonard Y., Andaya (2016). A History of Malaysia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-60515-3.

- Lai, Fanny (2016). Visual Celebrations of Borneo's Wildlife. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-146-291-907-9.

- Knapman, Gareth (2016). Race and British Colonialism in Southeast Asia, 1770–1870: John Crawfurd and the Politics of Equality. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-315-45216-6.

- Sidhu, Jatwan S. (2016). Historical Dictionary of Brunei Darussalam. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-6459-5.

- Epstein, M. (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1933. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-27062-6.

- Pateman, Colin (2017). B-24 Bridge Busters: RAF Liberators Over Burma. Fonthill Media. GGKEY:ZSXA7694KY6.

- Aspalter, Christian (2017). Health Care Systems in Developing Countries in Asia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-12313-2.

- Welman, Frans (2017). Borneo Trilogy Sarawak: Volume 1. Booksmango. ISBN 978-616-245-082-2.

- Press, Steven (2017). Rogue Empires: Contracts and Conmen in Europe's Scramble for Africa. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97185-1.

- Uncle DI (2017). "Nibbling at land rights of indigenous peoples". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017.

- Tawie, Sulok (2017). "Sarawak Museum to close until 2020 for restoration". Malay Mail Online. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Sarawak Health (2012). Heritage in Health: The Story of Medical and Health Care Services in Sarawak. Sarawak State Health Department, Kuching. ISBN 978-967-10800-1-6.

- Ledingham Christie, W (17 July 1915). "Further investigations into latent dysentery and intestinal parasitism in Sarawak, Borneo". British Medical Journal. 2 (2846): 89–90. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2846.89. PMC 2302560. PMID 20767729.

- Yadav, H (3 September 1990). "Cholera in Sarawak: A historical perspective (1873-1989)" (PDF). Medical Journal Malaysia. 45 (3): 194–201. PMID 2152080.

Further reading

- Keppel, Henry; Brooke, James; WalterKeating, Kelly (1847). "The expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the suppression of piracy : with extracts from the journal of James Brooke, Esq., of Sarawak". University of California Libraries. London : Chapman and Hall. p. 347.

- Low, Hugh (1848). "Sarawak; its inhabitants and productions: being notes during a residence in that country with His Excellency Mr. Brooke". Robarts Library, University of Toronto Libraries. London, Richard Bentley. p. 466.

- Jacob, Gertrude Le Grand (1876). "The Raja of Sarawak : An account of Sir James Brooke, K.C.B., LL.D., given chiefly through letters and journals". University of Michigan Library. London : Macmillan and co. p. 413.

- St. John, Spencer (1879). "The Life of Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak: From His Personal Papers and Correspondence". University of California Libraries. W. Blackwood. p. 433.

- Treacher, W. H (1891). "British Borneo: sketches of Brunai, Sarawak, Labuan, and North Borneo". University of California Libraries. Singapore, Govt. print. dept. p. 190.

- Roth, Henry Ling; Low, Hugh Brooke (1896). "The natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo; based chiefly on the mss. of the late H. B. Low, Sarawak government service". University of Michigan Library. London, Truslove & Hanson. p. 503.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine; Bampfylde, Charles Agar (1909). "A history of Sarawak under its two white Rajahs, 1839–1908". Robarts Library, University of Toronto Libraries. London, Richard Bentley. p. 466.

- Runciman, Steven (1960). "The White Rajahs". Cambridge University Press. University of Allahabad, Digital Library of India. p. 340.

- "Sarawak: A Kingdom in the Jungle". The New York Times. 1986. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017.

- "Chronology of Sarawak throughout the Brooke Era to Malaysia Day". The Borneo Post. 2011. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017.

- "Sarawak: A Most Unusual Territory". The London Gazette. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017.

- "The Brooke Era (1841 â€" 1941)". Sarawak State Government. 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017.

- Yap, Joanna (2016). "Tracing influence of Brunei and Sambas in formation of S'wak". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raj of Sarawak. |

- The Brooke Trust – More information on heritage of the Brooke dynasty

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)