Cannabis indica

Cannabis indica is an annual plant in the family Cannabaceae.[1] It is a putative species of the genus Cannabis. Whether it and Cannabis sativa are truly separate species is a matter of debate. The Cannabis indica plant is cultivated for many purposes; for example, the plant fibers can be converted into cloth. Cannabis indica produces large amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).[2] The higher concentrations of THC provide euphoric effects making it popular for use both as a recreational and medicinal drug.

| Cannabis indica | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Purple Kush | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis |

| Species: | C. indica |

| Binomial name | |

| Cannabis indica | |

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

|

Taxonomy

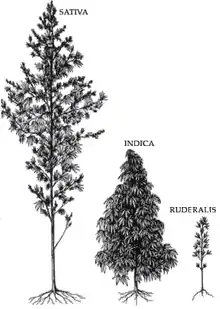

In 1785, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck published a description of a second species of Cannabis, which he named Cannabis indica. Lamarck based his description of the newly named species on plant specimens collected in India. Richard Evans Schultes described C. indica as relatively short, conical, and densely branched, whereas C. sativa was described as tall and laxly branched.[3] Loran C. Anderson described C. indica plants as having short, broad leaflets whereas those of C. sativa were characterized as relatively long and narrow.[4][5] Cannabis indica plants conforming to Schultes's and Anderson's descriptions originated from the Hindu Kush mountain range. Because of the often harsh and variable (extremely cold winters, and warm summers) climate of those parts, C. indica is well-suited for cultivation in temperate climates.[6] There was very little debate about the taxonomy of Cannabis until the 1970s, when botanists like Richard Evans Schultes began testifying in court on behalf of accused persons, who sought to avoid criminal charges of possession of Cannabis sativa by arguing that the plant material could instead be Cannabis indica.[7]

Cultivation

Broad-leafed Cannabis indica plants in the Indian Subcontinent are traditionally cultivated for the production of charas, a form of hashish. Pharmacologically, C. indica landraces tend to have higher THC content than C. sativa strains[8][9] Some users report more of a "stoned" feeling and less of a "high" from C. indica when compared to C. sativa. (The terms sativa and indica, used in this sense, are more appropriately termed "narrow-leaflet" drug type and "wide-leaflet" drug type Cannabis indica (or Cannabis sativa subsp. indica depending on the monotypic or polytipic point of view), respectively.[10]) The Cannabis indica high is often referred to as a "body buzz" and has beneficial properties such as pain relief in addition to being an effective treatment for insomnia and an anxiolytic, as opposed to sativa's more common reports of a cerebral, creative and energetic high, and even, albeit rarely, comprising hallucinations.[11] Differences in the terpenoid content of the essential oil may account for some of these differences in effect.[12][13] Common indica strains for recreational or medicinal use include Kush and Northern Lights.

A recent genetic analysis included both the narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug "biotypes" under C. indica, as well as southern and eastern Asian hemp (fiber/seed) landraces and wild Himalayan populations.[14]

Broad leaf of a C. indica plant

Broad leaf of a C. indica plant Cannabis

Cannabis.jpg.webp) Cannabis indica flowering

Cannabis indica flowering

Difference between C. indica and C. sativa

There are several key differences between Cannabis indica and Cannabis sativa. These include height and stature, internodal length, leaf size and structure, buds size and density, flowering time, odour, smoke and effects.[15] Indica plants tend to grow shorter and bushier than the sativa plants. Indica strains tend to have wide, short leaves with short wide blades, whereas sativa strains have long leaves with thin long blades. The buds of indica strains tend to be wide, dense and bulky, while sativa strains are likely to be long, sausage shaped flowers.[16]

On average, Cannabis indica has higher levels of THC compared to CBD, whereas Cannabis sativa has lower levels of THC to CBD.[9] However, huge variability exists within either species. A 2015 study shows the average THC content of the most popular herbal cannabis products in the Netherlands has decreased slightly since 2005.[17]

In the recent era of cannabis breeding higher-ratio CBD strains are being developed from Indica origins that may test out as 1:1 (CBD-THC balanced) or even as high as a 22:1 (CBD dominant). The medical interests in Cannabis are taking this further and we will see increasing cultivation trends for more strains developed with CBD-dominant ratios. In California, cities such as Coachella and Desert Hot Springs are re-zoning areas for cannabis cultivation. Even though Californians legalized recreational use of cannabis in late 2016, the LA Times, prior to the vote, reported an entrepreneurial focus on CBD-dominant medical hemp crops, "The demand for medical products was so high, this [380,000-square-foot (35,000 m2) cultivation expansion] was just to fill the need for that."[18] Low anxiety and hallucinogenic properties (psychoactive effects of THC reduced by CBD)[19] make these "high-CBD strains" very desirable for chronic treatment programs.

There are three chemotaxonomic types of Cannabis: one with high levels of THC, one which is more fibrous and has higher levels of CBD, and one that is an intermediate between the two.[9][20]

Cannabis strains with CBD:THC ratios above 5:2 are likely to be more relaxing and produce less anxiety than vice versa. This may be due to CBD's antagonistic effects at the cannabinoid receptors, compared to THC's partial agonist effect. CBD is also a 5-HT1A receptor (serotonin) agonist, which may also contribute to an anxiolytic-content effect.[21] The effects of sativa are well known for its cerebral high. Users can expect a more vivid and uplifting high, while indica is well known for its sedative effects which some prefer for night time use. Indica possesses a more calming, soothing, and numbing experience in which can be used to relax or relieve pain. Both types are used as medical cannabis.

During the 1970s, Cannabis indica strains from Afghanistan and Northern Pakistan particularly from the Hindu Kush mountain range were brought to the United States, where the first hybrids with Cannabis sativa plants from equatorial areas were developed, widely spreading marijuana cultivation throughout the States.[22]

Plants with elevated levels of propyl cannabinoids, including tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV), have been found in populations of Cannabis indica from India, Nepal, Thailand, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, as well as southern and western Africa. THCV levels up to 53.7% of total cannabinoids have been reported[9][23]

The name indica originally referred to the geographical area in which the plant was grown.[24] Whether C. sativa and C. indica are separate species is still a matter of debate.[25] However, investigation into chemotaxonomic differences support a two-species hypothesis.[9]

Genome

In 2011, a team of Canadian researchers led by Andrew Sud announced that they had sequenced a draft genome of the Purple Kush variety of C. indica.[26]

See also

References

- Cervantes, Jorge (2002). Indoor Marijuana Horticulture. p. 256. ISBN 9781878823298.

- "Marijuana Concentrates" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Agency. December 2014.

- Richard Evans Schultes; William M. Klein; Timothy Plowman & Tom E. Lockwood (1974). "Cannabis: an example of taxonomic neglect" (PDF). Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets. 23: 337–367.

- Loran C. Anderson (1980). "Leaf variation among Cannabis species from a controlled garden". Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets. 28 (1): 61–69.

- Dr. Loran C. Anderson - FSU Biological Science Faculty Emeritus

- "How to Grow Marijuana in Sub-tropical and Temperate Climates". MSNL Blog. 2017-05-09. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- Bosse, Jocelyn (2020). "Before the High Court: the legal systematics of Cannabis". Griffith Law Review: 1–28. doi:10.1080/10383441.2020.1804671.

- Fischedick, Justin Thomas; Hazekamp, Arno; Erkelens, Tjalling; Choi, Young Hae; Verpoorte, Rob (December 2010). "Metabolic fingerprinting of Cannabis sativa L., cannabinoids and terpenoids for chemotaxonomic and drug standardization purposes". Phytochemistry. 71 (17–18): 2058–2073. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.001. PMID 21040939.

- Karl W. Hillig; Paul G. Mahlberg (2004). "A chemotaxonomic analysis of cannabinoid variation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 91 (6): 966–975. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.6.966. PMID 21653452.

- "Sativa vs Indica." AMSTERDAM – THE CHANNELS. Web. 05 Dec. 2010. <http://www.channels.nl/knowledge/25700.html Archived 2014-11-16 at the Wayback Machine>.

- "Difference Marijuana Cannabis Sativa and Indica, Sativa or Indica Marijuana Seed Strains". Amsterdam Marijuana Seeds Seed Bank. Archived from the original on 2012-05-12. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- McPartland, J. M.; Russo, E. B. (2001). "Cannabis and Cannabis extracts: greater than the sum of their parts?". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 1 (3/4): 103–132. doi:10.1300/J175v01n03_08.

- Karl W. Hillig (2004). "A chemotaxonomic analysis of terpenoid variation in Cannabis". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 32 (10): 875–891. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2004.04.004.

- Karl W. Hillig (2005). "Genetic evidence for speciation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae)". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 52 (2): 161–180. doi:10.1007/s10722-003-4452-y. S2CID 24866870.

- "Indica vs Sativa – Differences". Freedom Seeds. Archived from the original on 2014-09-09. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- Ed, Rosenthal (2010). Marijuana Grower's Handbook (Ask ed.). Oakland, California: Quick American Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-932551-46-7.

- Niesink RJ, Rigter S, Koeter MW, Brunt TM (2015). "Potency trends of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and cannabinol in cannabis in the Netherlands: 2005-15". Addiction. 110 (12): 1941–50. doi:10.1111/add.13082. PMID 26234170.

- "This California desert town is experiencing a marijuana boom".

- Russo, EB (2011). "Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects". Br. J. Pharmacol. 163 (7): 1344–64. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x. PMC 3165946. PMID 21749363.

- Fischedick, Justin Thomas; Hazekamp, Arno; Erkelens, Tjalling; Choi, Young Hae; Verpoorte, Rob (December 2010). "Metabolic fingerprinting of Cannabis indica L., cannabinoids and terpenoids for chemotaxonomic and drug standardization purposes". Phytochemistry. 71 (17–18): 2058–2073. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.001. PMID 21040939.

- J.E. Joy; S. J. Watson Jr.; J.A. Benson Jr (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing The Science Base. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-0-585-05800-9.

- Tom Flowers, Marijuana flower forcing, Quick American Archives, 1997, p.48

- Turner, C.E.; Hadley, K.W.; Fetterman, P. (1973). "Constituents of Cannabis Sativa L., VI: Propyl Homologues in Samples of Known Geographical Origin". J. Pharm. Sci. 62 (10): 1739–1741. doi:10.1002/jps.2600621045. PMID 4752132.

- Nakamura, George (1973). "The forensic identification of marijuana: some questions and answers". Journal of Police Science and Administration: 102–112.

- Russo, EB (August 2007). "History of cannabis and its preparations in saga, science, and sobriquet". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 4 (8): 1614–48. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790144. PMID 17712811. S2CID 42480090.

- Van Bakel, H.; Stout, J. M.; Cote, A. G.; Tallon, C. M.; Sharpe, A. G.; Hughes, T. R.; Page, J. E. (2011). "The draft genome and transcriptome of Cannabis sativa". Genome Biol. 12 (10): R102. doi:10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-r102. PMC 3359589. PMID 22014239.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Cannabis indica. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cannabis indica. |