History of Belarus

This article describes the history of Belarus. The Belarusian ethnos is traced at least as far in time as other East Slavs.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Belarus |

| Prehistory |

| Middle ages |

| Early Modern |

|

| Modern |

|

|

|

After an initial period of independent feudal consolidation, Belarusian lands were incorporated into the Kingdom of Lithuania, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Russian Empire and eventually the Soviet Union. Belarus became an independent country in 1991 after declaring itself free from the Soviet Union.

Early history

.png.webp)

The history of Belarus, or more precisely of the Belarusian ethnicity, begins with the migration and expansion of the Slavic peoples through Eastern Europe between the 6th and 8th centuries. East Slavs settled on the territory of present-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, assimilating local Baltic (Yotvingians, Dniepr Balts), Finno-Ugric (in Russia) and steppe nomads (in Ukraine) already living there, their early ethnic integrations contributed to the gradual differentiation of the three East Slavic nations. These East Slavs, pagan, animistic, agrarian people, had an economy which included trade in agricultural produce, game, furs, honey, beeswax and amber.

The modern Belarusian ethnos was probably formed on the basis of the three Slavic tribes — Kryvians, Drehovians, Radzimians as well as several Baltic tribes.

During the 9th and 10th centuries, Scandinavian Vikings established trade posts on the way from Scandinavia to the Byzantine Empire. The network of lakes and rivers crossing East Slav territory provided a lucrative trade route between the two civilizations. In the course of trade, they gradually took sovereignty over the tribes of East Slavs, at least to the point required by improvements in trade.

The Rus' rulers invaded the Byzantine Empire on few occasions, but eventually they allied against the Bulgars. The condition underlying this alliance was to open the country for Christianization and acculturation from the Byzantine Empire.

The common cultural bond of Eastern Orthodox Christianity and written Church Slavonic (a literary and liturgical Slavic language developed by 8th century missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius) fostered the emergence of a new geopolitical entity, Kievan Rus' — a loose-knit multi-ethnic network of principalities,[1] established along preexisting trade routes, with major centers in Novgorod (currently Russia), Polatsk (in Belarus) and Kyiv (currently in Ukraine) — which claimed a sometimes precarious preeminence among them.

First Belarusian states

Between the 9th and 12th centuries, the Principality of Polotsk (northern Belarus) emerged as the dominant center of power on the Belarusian territory, while the Principality of Turaŭ in the south had a lesser power.

Principality of Polotsk repeatedly asserted its sovereignty in relation to the other centers of Rus', becoming a political capital, the episcopal see of a bishopric and the controller of vassal territories among Balts in the west. The city's Cathedral of the Holy Wisdom (1044–66), though completely rebuilt over the years, remains a symbol of this independent-mindedness, rivaling churches of the same name in Novgorod and Kiev, referring to the original Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (and hence to claims of imperial prestige, authority and sovereignty). Cultural achievements of the Polatsk period include the work of the nun Euphrosyne of Polatsk (1120–1173), who built monasteries, transcribed books, promoted literacy and sponsored art (including local artisan Lazarus Bohsha's famous "Cross of Euphrosyne", a national symbol and treasure stolen during World War II), and the prolific, original Church Slavonic sermons and writings of Bishop Cyril of Turau (1130–1182).

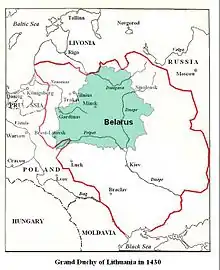

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

In the 13th century, the fragile unity of Kievan Rus' disintegrated due to nomadic incursions from Asia, which climaxed with the Mongol sacking of Kiev (1240), leaving a geopolitical vacuum in the region. The East Slavs splintered into a number of independent and competing principalities. Due to military conquest and dynastic marriages, the West Ruthenian (Belarusian) principalities were acquired by the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania, beginning with the rule of Lithuanian King Mindaugas (1240–1263). From the 13th to 15th century, principalities were annexed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, with its initial capital unknown, but which presumably could have been Voruta, later capital was moved to Kernavė then Trakai and finally to Vilnius. Since the 14th century, Vilnius had been the only official capital of the state.

The Lithuanians' smaller numbers in this medieval state gave the Ruthenians (present-day Belarusians and Ukrainians) an important role in the everyday cultural life of the state. Owing to the prevalence of East Slavs and the Eastern Orthodox faith among the population in eastern and southern regions of the state, the Ruthenian language was a widely used colloquial language.

An East Slavic variety (rus'ka mova, Old Belarusian or West Russian Chancellery language), gradually influenced by Polish, was the language of administration in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at least since Vytautas' reign until the late 17th century when it was eventually replaced by Polish language.[2]

This period of political breakdown and reorganization also saw the rise of written local vernaculars in place of the literary and liturgical Church Slavonic language, a further stage in the evolving differentiation between the Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian languages.

Several Lithuanian monarchs — the last being Švitrigaila in 1432–36 — relied on the Eastern Orthodox Ruthenian majority, while most monarchs and magnates increasingly came to reflect the opinions of the Roman Catholics.

Construction of Orthodox churches in some parts of present-day Belarus had been initially prohibited, as was the case of Vitebsk in 1480. On the other hand, further unification of the, mostly Orthodox, Grand Duchy with mostly Catholic Poland led to liberalization and partial solving of the religious problem. In 1511, King and Grand Duke Sigismund I the Old granted the Orthodox clergy an autonomy enjoyed previously only by Catholic clergy. The privilege was enhanced in 1531, when the Orthodox church was no longer responsible to the Catholic bishop and instead the Metropolite was responsible only to the sobor of eight Orthodox bishops, the Grand Duke and the Patriarch of Constantinople. The privilege also extended the jurisdiction of the Orthodox hierarchy over all Orthodox people.[3]

In such circumstances, a vibrant Ruthenian culture flourished, mostly in major present-day Belarusian cities.[4] Despite the legal usage of the Old Ruthenian language (the predecessor of both modern Belarusian and Ukrainian languages) which was used as a chancellery language in the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the literature was mostly non-existent, outside of several chronicles. The first Belarusian book printed with the first printing press in the Cyrillic alphabet was published in Prague in 1517, by Francysk Skaryna, a leading representative of the renaissance Belarusian culture. Soon afterwards he founded a similar printing press in Polatsk and started an extensive undertaking of publishing the Bible and other religious works there. Apart from the Bible itself, before his death in 1551 he published 22 other books, thus laying the foundations for the evolution of the Ruthenian language into the modern Belarusian language.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Lublin Union of 1569 constituted the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as an influential player in European politics and the largest multinational state in Europe. While Ukraine and Podlaskie became subjects to the Polish Crown, present-day Belarus territory was still regarded as part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The new polity was dominated by densely populated Poland, which had 134 representatives in the Sejm as compared to 46 representatives from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. However the Grand Duchy of Lithuania retained much autonomy, and was governed by a separate code of laws called the Lithuanian Statutes, which codified both civil and property rights. Mogilyov was the largest urban centre of the territory of present-day Belarus, followed by Vitebsk, Polotsk, Pinsk, Slutsk, and Brest, whose population exceeded 10,000. In addition, Vilna (Vilnius), the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, also had a significant Ruthenian population.[5]

With time, the ethnic pattern did not evolve much. Throughout their existence as a separate culture, Ruthenians formed in most cases rural population, with the power held by local szlachta and boyars, often of Lithuanian, Polish or Russian descent. By this time, a significant Jewish presence had also formed in this region of German Jews fleeing persecution from the Northern and Baltic Crusaders. Since the Union of Horodlo of 1413, local nobility was assimilated into the traditional clan system by means of the formal procedure of adoption by the szlachta (Polish gentry). Eventually it formed a significant part of the szlachta. Initially mostly Ruthenian and Orthodox, with time most of them became polonized. This was especially true for major magnate families (Sapieha and Radziwiłł clans being the most notable), whose personal fortunes and properties often surpassed those of the royal families and were huge enough to be called a state within a state. Many of them founded their own cities and settled them with settlers from other parts of Europe. Indeed, there were Scots, Germans and Dutch people inhabiting major towns of the area, as well as several Italian artists who had been "imported" to the lands of modern Belarus by the magnates. Contrary to Poland, in the lands of the Grand Duchy, the peasants had little personal freedom in the Middle Ages. However, with time, the magnates and the gentry gradually limited the few liberties of the serfs, at the same time increasing their taxation, often in labour for the local gentry. This made many Ruthenians flee to the scarcely populated lands, Dzikie Pola (Wild Fields), the Polish name of the Zaporizhian Sich, where they formed a large part of the Cossacks. Others sought refuge in the lands of other magnates or in Russia.

Also, with time the religious conflicts started to arise. The gentry with time started to adopt Catholicism while the common people by large remained faithful to Eastern Orthodoxy. Initially the Warsaw Compact of 1573 codified the preexisting freedom of worship. However, the rule of an ultra-Catholic King Sigismund III Vasa was marked by numerous attempts to spread the Catholicism, mostly through his support for counterreformation and the Jesuits. Possibly to avoid such conflicts, in 1595 the Orthodox hierarchs of Kiev signed the Union of Brest, breaking their links with the Patriarch of Constantinople and placing themselves under the Pope. Although the union was generally supported by most local Orthodox bishops and the king himself, it was opposed by some prominent nobles and, more importantly, by the nascent Cossack movement. This led to a series of conflicts and rebellions against the local authorities. The first of such happened in 1595, when the Cossack insurgents under Severyn Nalivaiko took the towns of Slutsk and Mogilyov and executed Polish magistrates there. Other such clashes took place in Mogilyov (1606–10), Vitebsk (1623), and Polotsk (1623, 1633).[6] This left the population of the Grand Duchy divided between Greek Catholic and Greek Orthodox parts. At the same time, after the schism in the Orthodox Church (Raskol), some Old Believers migrated west, seeking refuge in the Rzeczpospolita, which allowed them to freely practice their faith.[7]

From 1569, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth suffered a series of Tatar invasions, the goal of which was to loot, pillage and capture slaves into jasyr. The borderland area to the south-east was in a state of semi-permanent warfare until the 18th century. Some researchers estimate that altogether more than 3 million people, predominantly Ukrainians but also Russians, Belarusians and Poles, were captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate.

Despite the abovementioned conflicts, the literary tradition of Belarus evolved. Until the 17th century, the Ruthenian language, the predecessor of modern Belarusian, was used in Grand Duchy as a chancery language, that is the language used for official documents. Afterwards, it was replaced with the Polish language, commonly spoken by the upper classes of Belarusian society. Both Polish and Ruthenian cultures gained a major cultural centre with the foundation of the Academy of Vilna. At the same time the Belarusian lands entered a path of economic growth, with the formation of numerous towns that served as centres of trade on the east–west routes.

However, both economic and cultural growth came to an end in mid-17th century with a series of violent wars against Tsardom of Russia, Sweden, Brandenburg and Transylvania, as well as internal conflicts, known collectively as The Deluge. The misfortunes were started in 1648 by Bohdan Chmielnicki, who started a large-scale Cossack uprising in Ukraine. Although the Cossacks were defeated in 1651 in the battle of Beresteczko, Khmelnytsky sought help from Russian tsar, and by the Treaty of Pereyaslav Russia dominated and partially occupied the eastern lands of the Commonwealth since 1655. The Swedes invaded and occupied the rest in the same year. The wars had shown internal problems of the state, with some people of the Grand Duchy supporting Russia[8] while others (most notably Janusz Radziwiłł) supporting the Swedes. Although the Swedes were finally driven back in 1657 and the Russians were defeated in 1662, most of the country was ruined. It is estimated that the Commonwealth lost a third of its population, with some regions of Belarus losing as much as 50%. This broke the power of the once-powerful Commonwealth and the country gradually became vulnerable to foreign influence.

Subsequent wars in the area (Great Northern War and the War of Polish succession) damaged its economy even further. In addition, Russian armies raided the Commonwealth under the pretext of the returning of fugitive peasants.[7] By mid-18th century their presence in the lands of modern Belarus became almost permanent.

The last attempt to save the Commonwealth's independence was a Polish–Belarusian–Lithuanian national uprising of 1794 led by Tadeusz Kościuszko, however it was eventually quenched.

Eventually by 1795 Poland was partitioned by its neighbors. Thus a new period in Belarusian history started, with all its lands annexed by the Russian Empire, in a continuing endeavor of Russian tsars of "gathering the Rus lands" started after the liberation from the Tatar yoke by Grand Duke Ivan III of Russia.

Russian Empire

.jpg.webp)

Under Russian administration, the territory of Belarus was divided into the guberniyas of Minsk, Vitebsk, Mogilyov, and Hrodno. Belarusians were active in the guerrilla movement against Napoleon's occupation.[9]. With Napoleon's defeat, Belarus again became a part of Imperial Russia and its guberniyas constituted part of the Northwestern Krai. The anti-Russian uprisings of the gentry[10] in 1830 and 1863 were subdued by government forces.

Although under Nicholas I and Alexander III the national cultures were repressed due to the policies of de-Polonization[11] and Russification,[10] which included the return to Orthodoxy, the 19th century signifies the rise of the modern Belarusian nation and self-confidence. A number of authors started publishing in the Belarusian language, including Jan Czeczot, Władysław Syrokomla and Konstanty Kalinowski.

In a Russification drive in the 1840s, Nicholas I forbade the use of the term Belarusia and renamed the region the "North-Western Territory". He also prohibited the use of Belarusian language in public schools, campaigned against Belarusian publications and tried to pressure those who had converted to Catholicism under the Poles to reconvert to the Orthodox faith. In 1863, economic and cultural pressure exploded into a revolt, led by Kalinowski. After the failed revolt, the Russian government reintroduced the use of Cyrillic to Belarusian in 1864 and banned the use of the Latin alphabet.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Belarusian economy, like that of the entire Europe, was experiencing significant growth due to the spread of the Industrial Revolution to Eastern Europe,[12] particularly after the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. Peasants sought a better lot in foreign industrial centres, with some 1.5 million people leaving Belarus in the half-century preceding the Russian Revolution of 1917.

20th century

BNR and LBSSR

_Map_1918.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

On 21 February 1918, Minsk was captured by German troops. World War I was the short period when Belarusian culture started to flourish. German administration allowed schools with Belarusian language, previously banned in Russia; a number of Belarusian schools were created until 1919 when they were banned again by the Polish military administration. At the end of World War I, when Belarus was still occupied by Germans, according to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the short-lived People's Republic of Belarus was pronounced on 25 March 1918, as part of the German Mitteleuropa plan.

In December 1918, Mitteleuropa was obsolete as the German Empire withdrew from the Ober-Ost territory, and for the next few years in the newly created power vacuum the territories of Belarus would witness the struggle of various national and foreign factions. On 3 December 1918 the Germans withdrew from Minsk. On 10 December 1918 Soviet troops occupied Minsk. The Rada (Council) of the People's Republic of Belarus went into exile, first to Kaunas, then to Berlin and finally to Prague. On 2 January 1919, the Soviet Socialist Republic of Byelorussia was declared. On 17 February 1919 it was disbanded. Part of it was included into Russian SFSR, and part was joined to the Lithuanian SSR to form the LBSSR, Lithuanian–Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, informally known as Litbel, whose capital was Vilnius. While Belarus National Republic faced off with Litbel, foreign powers were preparing to reclaim what they saw as their territories: Polish forces were moving from the West, and Russians from the East. When Vilnius was captured by Polish forces on 17 April 1919, the capital of the Soviet puppet state Litbel was moved to Minsk. On 17 July 1919 Lenin dissolved Litbel because of the pressure of Polish forces advancing from the West. Polish troops captured Minsk on 8 August 1919.

Republic of Central Lithuania

The Republic of Central Lithuania was a short-lived political entity, which was the last attempt to restore Lithuania in the historical confederacy state (it was also supposed to create Lithuania Upper and Lithuania Lower). The republic was created in 1920 following the staged rebellion of soldiers of the 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division of the Polish Army under Lucjan Żeligowski. Centered on the historical capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilna (Lithuanian: Vilnius, Polish: Wilno), for 18 months the entity served as a buffer state between Poland, upon which it depended, and Lithuania, which claimed the area.[13] After a variety of delays, a disputed election took place on 8 January 1922, and the territory was annexed to Poland. Żeligowski later in his memoir which was published in London in 1943 condemned the annexation of Republic by Poland, as well as the policy of closing Belarusian schools and general disregard of Marshal Józef Piłsudski's confederation plans by Polish ally.[14]

Belarusian Soviet Republic and West Belarus

Some time in 1918 or 1919, Sergiusz Piasecki returned to Belarus, joining Belarusian anti-Soviet units, the "Green Oak" (in Polish, Zielony Dąb), led by Ataman Wiaczesław Adamowicz (pseudonym: J. Dziergacz). When on 8 August 1919, the Polish Army captured Minsk, Adamowicz decided to work with them. Thus Belarusian units were created, and Piasecki was transferred to a Warsaw school of infantry cadets. In the summer of 1920, during the Polish–Soviet War, Piasecki fought in the Battle of Radzymin.

The frontiers between Poland, which had established an independent government after World War I, and the former Russian Empire were not recognized by the League of Nations. Poland's Józef Piłsudski, who envisioned the formation of an Intermarium federation as a Central and East European bloc that would be a bulwark against Germany to the west and Russia to the east, carried out a Kiev Offensive into Ukraine in 1920. This met with a Red Army counter-offensive that drove into Polish territory almost to Warsaw, Minsk itself was re-captured by the Soviet Red Army on 11 July 1920 and a new Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic was declared on 31 July 1920. Piłsudski, however, halted the Soviet advance at the Battle of Warsaw and resumed his eastward offensive. Finally the Treaty of Riga, ending the Polish–Soviet War, divided Belarus between Poland and Soviet Russia. Over the next two years, the People's Republic of Belarus prepared a national uprising, ceasing the preparations only when the League of Nations recognized the Soviet Union's western borders on 15 March 1923. The Soviets terrorised Western Belarus, the most radical case being Soviet raid on Stołpce. Poland created Border Protection Corps in 1924.

The Polish part of Belarus was subject to Polonization policies (especially in the 1930s), while the Soviet Belarus was one of the original republics which formed the USSR. For several years, the national culture and language enjoyed a significant boost of revival in the Soviet Belarus. A Polish Autonomous District was also formed. This was however soon ended during the Great Purge, when almost all prominent Belarusian national intelligentsia were executed, many of them buried in Kurapaty. Thousands were deported to Asia. As the result of Polish operation of the NKVD tens of thousands people of many nationalities were killed. Belarusian orthography was Russified in 1933 and use of Belarusian language was discouraged as exhibiting anti-soviet attitude.[15]

In West Belarus, up to 30,000 families of Polish veterans (osadniks) were settled in the lands formerly belonging to the Russian tsar family and Russian aristocracy.[16] Belarusian representation in Polish parliament was reduced as a result of the 1930 elections. Since the early 1930s, the Polish government introduced a set of policies designed to Polonize all minorities (Belarusians, Ukrainians, Jews, etc.). The usage of Belarusian language was discouraged and the Belarusian schools were facing severe financial problems. In spring of 1939, there already was neither single Belarusian official organisation in Poland nor a single exclusively Belarusian school (with only 44 schools teaching Belarusian language left).[17]

Belarus in World War II

When the Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, 1939, following the terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact's secret protocol, Western Byelorussia, which was part of Poland, is included in the BSSR. Similarly to the times of German occupation during World War I, Belarusian language and Soviet culture enjoyed relative prosperity in this short period. Already in October 1940, over 75% of schools used the Belarusian language, also in the regions where no Belarus people lived, e.g. around Łomża, what was Ruthenization.[18] Western Belarus was sovietised, tens of thousands were imprisoned, deported, murdered. The victims were mostly Polish and Jewish.[19][20]

After twenty months of Soviet rule, Nazi Germany and its Axis allies invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. Soviet authorities immediately evacuated about 20% of the population of Belarus, killed thousands of prisoners and destroyed all the food supplies.[21] The country suffered particularly heavily during the fighting and the German occupation. Minsk was captured by the Germans on 28 June 1941. Following bloody encirclement battles, all of the present-day Belarus territory was occupied by the Germans by the end of August 1941.

During World War II, the Nazis attempted to establish a puppet Belarusian government, Belarusian Central Rada, with the symbolics similar to BNR. In reality, however, the Germans imposed a brutal racist regime, burning down some 9,000 Belarusian villages, deporting some 380,000 people for slave labour, and killing hundreds of thousands of civilians more. Local police took part in many of those crimes. Almost the whole, previously very numerous, Jewish populations of Belarus that did not evacuate were killed. One of the first uprisings of a Jewish ghetto against the Nazis occurred in 1942 in Belarus, in the small town of Lakhva.

Since the early days of the occupation, a powerful and increasingly well-coordinated Belarusian resistance movement emerged. Hiding in the woods and swamps, the partisans inflicted heavy damage to German supply lines and communications, disrupting railway tracks, bridges, telegraph wires, attacking supply depots, fuel dumps and transports and ambushing German soldiers. Not all anti-German partisans were pro-Soviet.[22] In the largest partisan sabotage action of the entire Second World War, the so-called Asipovichy diversion of 30 July 1943 four German trains with supplies and Tiger tanks were destroyed. To fight partisan activity, the Germans had to withdraw considerable forces behind their front line. On 22 June 1944 the huge Soviet offensive Operation Bagration was launched, Minsk was re-captured on 3 July 1944, and all of Belarus was regained by the end of August. Hundred thousand of Poles were expelled after 1944. As part of the Nazis' effort to combat the enormous Belarusian resistance during World War II, special units of local collaborationists were trained by the SS's Otto Skorzeny to infiltrate the Soviet rear. In 1944 thirty Belarusians (known as Čorny Kot (Black Cat) and personally led by Michał Vituška) were airdropped by the Luftwaffe behind the lines of the Red Army, which had already liberated Belarus during Operation Bagration. They experienced some initial success due to disorganization in the rear of the Red Army, and some other German-trained Belarusian nationalist units also slipped through the Białowieża Forest in 1945. The NKVD, however, had already infiltrated these units. Vituška himself was hunted down, captured and executed, although he continued to live on in Belarusian nationalist hagiography.[23]

In total, Belarus lost a quarter of its pre-war population in World War II including practically all its intellectual elite. About 9 200 villages and 1.2 million houses were destroyed. The major towns of Minsk and Vitsebsk lost over 80% of their buildings and city infrastructure. For the defence against the Germans, and the tenacity during the German occupation, the capital Minsk was awarded the title Hero City after the war. The fortress of Brest was awarded the title Hero-Fortress.

BSSR from 1945 to 1990

After the end of War in 1945, Belarus became one of the founding members of the United Nations Organisation. Joining Belarus was the Soviet Union itself and another republic Ukraine. In exchange for Belarus and Ukraine joining the UN, the United States had the right to seek two more votes, a right that has never been exercised.[24]

.jpg.webp)

More than 200,000 ethnic Poles left or were expelled to Poland in late 1940s and late 1950s, some killed by the NKVD or deported to Siberia. [25] Armia Krajowa and post-AK resistance was the strongest in the Hrodna, Vaŭkavysk, Lida and Ščučyn regions.[26]

The Belarusian economy was completely devastated by the events of the war. Most of the industry, including whole production plants were removed either to Russia or Germany. Industrial production of Belarus in 1945 amounted for less than 20% of its pre-war size. Most of the factories evacuated to Russia, with several spectacular exceptions, were not returned to Belarus after 1945. During the immediate postwar period, the Soviet Union first rebuilt and then expanded the BSSR's economy, with control always exerted exclusively from Moscow. During this time, Belarus became a major center of manufacturing in the western region of the USSR. Huge industrial objects like the BelAZ, MAZ, and the Minsk Tractor Plant were built in the country. The increase in jobs resulted in a huge immigrant population of Russians in Belarus. Russian became the official language of administration and the peasant class, which traditionally was the base for Belarusian nation, ceased to exist.[15]

On 26 April 1986, the Chernobyl disaster occurred at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine situated close to the border with Belarus. It is regarded as the worst nuclear accident in the history of nuclear power. It produced a plume of radioactive debris that drifted over parts of the western Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and Scandinavia. Large areas of Belarus, Ukraine and Russia were contaminated, resulting in the evacuation and resettlement of roughly 200,000 people. About 60% of the radioactive fallout landed in Belarus. The effects of the Chernobyl accident in Belarus were dramatic: about 50,000 km2 (or about a quarter of the territory of Belarus) formerly populated by 2.2 million people (or a fifth of the Belarusian population) now require permanent radioactive monitoring (after receiving doses over 37 kBq/m2 of caesium-137). 135,000 persons were permanently resettled and many more were resettled temporarily. After 10 years since the accident, the occurrences of thyroid cancer among children increased fifteenfold (the sharp rise started in about four years after the accident).[27]

Republic of Belarus

Pre-Alexander Lukashenko period

On 27 July 1990, Belarus declared its national sovereignty, a key step toward independence from the Soviet Union. Around that time, Stanislau Shushkevich became the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus, the top leadership position in Belarus.

On 25 August 1991, after the failure of the August coup in Moscow, Belarus declared full independence from the USSR by granting the declaration of state sovereignty a constitutional status that it did not have before.[28] On 8 December 1991, Shushkevich met with Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine, in Belavezhskaya Pushcha, to formally declare the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

Alexander Lukashenko period

In 1994, the first presidential elections were held and Alexander Lukashenko was elected president of Belarus. The 1996 referendum resulted in the amendment of the constitution that took key powers off the parliament. In 1999 opposition leaders Yury Zacharanka and Viktar Hanchar disappeared and were presumably killed. In 2001, Lukashenko was re-elected* as president in elections described as undemocratic by Western observers. At the same time, the west began criticizing him as authoritarian. In 2006, Lukashenko was once again re-elected* in presidential elections again criticized as flawed by most European Union countries.

In 2010, Lukashenko was re-elected once again in presidential elections which were again described as falsified by most EU countries and organizations such as the OSCE. A peaceful protest against the electoral flaws turned into a riot when demonstrators tried to storm a government building. The police used batons to quell the riot. Seven presidential candidates and hundreds of rioters were arrested by KGB.[29]

See also

- History of the Jews in Belarus

- History of Lithuania

- History of Poland

- History of Russia

- History of Ukraine

- List of Famous People of Belarus

- List of Belarusian rulers

- Polish Autonomous Districts: Dzierzynszczyzna, Marchlewszczyzna

References

- John Channon & Robert Hudson, Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia (Penguin, 1995), p.16.

- Björn Wiemer. "Dialect and language contacts on the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the 15th century until 1939". Aspects of Multilingualism in European Language History. Edited by Kurt Braunmüller and Gisell Ferraresi. John Benjamins Publishing. 2003. pp. 110–111.

- (in Russian) Литовско–русское государство (Litovsko–russkoye gosydarstvo) in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary

- (in Russian) "Братства" (Bratstva) in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary

- (in Russian) Внутриполитические результаты Люблинской унии (Vnutripolitičeskie rezul'tati Lyublinskoy unii), Belarus.by portal

- (in Russian) Церковная уния 1596 г. (Tserkovnaya uniya 1596 g.) in "belarus.by portal"

- (in Polish) Jerzy Czajewski, Zbiegostwo ludności Rosji w granice Rzeczypospolitej (Russian population exodus into the Rzeczpospolita), Promemoria journal, October 2004 nr. (5/15), ISSN 1509-9091, Table of Contents online Archived 12 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Russian) Белорусская Советская Социалистическая Республика (Belorusskaya Sovyetskaya Socialističeskaya Respublika), article in "Большая Советская Энциклопедия" (Great Soviet Encyclopedia). Last accessed in December 2005

- S., John. "History of Belarus was formed probably on the basis of the three Slavic tribes". John Learn. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Żytko, Anatol (1999) Russian policy towards the Belarussian gentry in 1861–1914, Minsk, p. 551.

- (in Russian) Воссоединение униатов и исторические судьбы Белорусского народа (Vossoyedineniye uniatov i istoričeskiye sud'bi Belorusskogo naroda), Pravoslavie portal

- (in Russian) История строительства дорог 1850–1900 гг. Archived 4 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Byelorussian Railways

- Rauch, Georg von (1974). "The Early Stages of Independence". In Gerald Onn (ed.). The Baltic States: Years of Independence – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, 1917–40. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 100–102. ISBN 0-903983-00-1.

- Żeligowski, Lucjan (1943). Zapomniane prawdy (PDF) (in Polish). F. Mildner & Sons.

- Janowicz, Sokrat (1999). Forming of the Belarussian nation. RYTM. pp. 247–248.

- (in Polish) Stobniak-Smogorzewska, Janina (2003) Kresowe osadnictwo wojskowe 1920–1945 (Military colonization of Kresy 1920–1945), Warsaw, RYTM, ISBN 83-7399-006-2

- (in Polish) Ogonowski, Jerzy (2000) Uprawnienia językowe mniejszości narodowych w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 1918–1939 (The Language Rights of National Minorities in the Second Republic of Poland, 1918–1939, Polish with an English summary), Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, Warsaw, pp. 164–165

- Ruchniewicz, Stosunki..., p254

- Jan T. Gross, Revolution from Abroad

- Franziska Exeler, "What Did You Do during the War?" Kritika: Explorations in Russian & Eurasian History (Fall 2016) 17#4 pp 805-835 examines behaviour World War II in Belarus under the Germans, using oral history, letters of complaint, memoirs and secret police and party reports.

- (in Polish) Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (1999) Białoruś, Trio, Warsaw, p. 136. ISBN 83-85660-82-8

- Strużyńska, Anti-Soviet conspiracy..., pp859–860.

- Alexander Perry Biddiscombe (2006). The SS Hunter Battalions: The Hidden History of the Nazi Resistance Movement 1944-45. Tempus. p. 66/67. ISBN 0752439383.

- "United Nations". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

Voting procedures and the veto power of permanent members of the Security Council were finalized at the Yalta Conference in 1945 when Roosevelt and Stalin agreed that the veto would not prevent discussions by the Security Council. Roosevelt agreed to General Assembly membership for Ukraine and Byelorussia while reserving the right, which was never exercised, to seek two more votes for the United States.

- Andrew Savchenko, Belarus: A Perpetual Borderland, page 135, BRILL, 2009, ISBN 9789004174481

- Strangers at Home: Memorialisation of the Armia Krajowa in Belarus, Iryna Kashtalian, Imre Kertész Kolleg’s Cultures of History Forum

- Последствия аварии на Чернобыльской АЭС. expo2000.bsu.by

- Belarus And The Independence Day That Wasn't - by Tom Balmforth, Radio Free Europe, 25 August 2011

- "'Hundreds of protesters arrested' in Belarus". BBC. 20 December 2010.

Further reading

- Baranova, Olga. "Nationalism, anti-Bolshevism or the will to survive? Collaboration in Belarus under the Nazi occupation of 1941–1944." European Review of History—Revue européenne d'histoire 15.2 (2008): 113–128.

- Bekus, Nelly. Struggle over Identity: The Official and the Alternative “Belarussianness” (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2010);

- Bemporad, Elissa. Becoming Soviet Jews: The Bolshevik Experiment in Minsk (Indiana UP, 2013).

- Bennett, Brian M. The last dictatorship in Europe: Belarus under Lukashenko (Columbia University Press, 2011)

- Defense Technical Information Center. Democratization and Instability in Ukraine, Georgia, and Belarus (2014) online

- Defense Technical Information Center. The Role of Small States in the Post-Cold War Era: The Case of Belarus (2012) online

- Fedor, Helen, Belarus and Moldova: country studies (Library of Congress. Federal Research Division, 1995) online, with brief history pp 18–25.

- Epstein, Barbara. The Minsk Ghetto 1941-1943: Jewish Resistance and Soviet Internationalism (U of California Press, 2008).

- Guthier, Steven L. "The Belorussians: National identification and assimilation, 1897–1970: Part 1, 1897–1939." Soviet Studies 29.1 (1977): 37–61.

- Horak, Stephan M. "Belorussia: Modernization, Human Rights, Nationalism." Canadian Slavonic Papers 16.3 (1974): 403–423.

- Korosteleva, Elena A., Lawson Colin W. and Marsh, Rosalind J., eds. Contemporary Belarus (Routledge 2003)

- Loftus, John J., 'The Belarus Secret'(Knopf, 1982)

- Lubachko, Ivan S. Belorussia: Under Soviet Rule, 1917--1957 (U Press of Kentucky, 2015).

- Marples, David R. "Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia Under Soviet Occupation: The Development of Socialist Farming, 1939-1941." Canadian Slavonic Papers' 27.2 (1985): 158- 177. online

- Marples, David. 'Our Glorious Past': Lukashenka's Belarus and the Great Patriotic War (Columbia University Press, 2014)

- Minahan, James (1998). Miniature Empires: A Historical Dictionary of the Newly Independent States. Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-30610-9.

- Olson, James Stuart; Pappas, Lee Brigance; Pappas, Nicholas C. J. (1994). Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27497-5.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2001). The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924739-0.

- Rudling, Pers Anders. The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906–1931 (University of Pittsburgh Press; 2014) 436 pages

- Ryder, Andrew (1998). Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, Volume 4. Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-058-1.

- Silitski, Vitali and Jan Zaprudnik (2010). The A to Z of Belarus. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461731740.

- Skinner, Barbara. (2012) The Western Front of the Eastern Church: Uniate and Orthodox Conflict in Eighteenth-Century Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia

- Smilovitsky, Leonid. "Righteous Gentiles, the Partisans, and Jewish Survival in Belorussia, 1941–1944." Holocaust and Genocide Studies 11.3 (1997): 301-329.

- Snyder, Timothy. (2004) The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999 excerpt and text search

- Strategic Studies Institute. Political Trends in the New Eastern Europe - Ukraine and Belarus (2007) online

- Strużyńska, Nina. Anti-Soviet conspiracy and partisan struggle of the Green Oak Party in Belarus, in Non Provincial Europe, London 1999, ISBN 83-86759-92-5

- Szporluk, Roman (2000). Russia, Ukraine, and the Breakup of the Soviet Union. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 0-8179-9542-0.

- Szporluk, Roman. "West Ukraine and West Belorussia: Historical tradition, social communication, and linguistic assimilation." Soviet Studies 31.1 (1979): 76-98. online

- Szporluk, Roman. "The press in Belorussia, 1955–65." Europe‐Asia Studies 18.4 (1967): 482-493.

- Treadgold, Donald; Ellison, Herbert J. (1999). Twentieth Century Russia. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3672-4.

- Urban, Michael E. An Algebra of Soviet Power: Elite Circulation in the Belorussian Republic 1966-86 (Cambridge UP, 1989).

- Vakar, Nicholas Platonovich. Belorussia: the making of a nation: a case study (Harvard UP, 1956).

- Vakar, Nicholas Platonovich. A bibliographical guide to Belorussia (Harvard UP, 1956).

- Vauchez, André; Dobson, Richard Barrie; Lapidge, Michael (2001). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Routledge. ISBN 1-57958-282-6.

- Wexler, Paul. "Belorussification, Russification and Polonization Trends in the Belorussian Language 1890-1982." in Kreindler, ed., Sociolinguistic Perspectives (1985): 37-56.

- Zaprudnik, Jan. Historical dictionary of Belarus (Scarecrow Pr, 1998)

- Zaprudnik. Jan. Belarus: At A Crossroads In History (Westview Press, 1993) online free to borrow}

In Polish

- (in Polish) Piotr Eberhardt, Problematyka narodowościowa Białorusi w XX wieku ("Nationality issue of Belarus in the 20th century"), Lublin, 1996, ISBN 83-85854-16-9

- (in Polish) Ryszard Radzik, Kim są Białorusini? (Who are the Belarusians?), Toruń 2003, ISBN 83-7322-672-9

- (in Polish) Małgorzata Ruchniewicz, Stosunki narodowościowe w latach 1939–1948 na obszarze tzw. Zachodniej Białorusi in Przemiany narodowościowe na kresach wschodnich II Rzeczypospolitej 1931–1948 (Nationality relations in 1939–1948 on the territory of so-called Western Belarus), Toruń, 2004, ISBN 83-7322-861-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Belarus. |

- Belarus National Republic — the Belarusian Government in exile

- Stary Hetman — forums and library (in Belarusian and Russian) on Belarusian history

- Belarus, by CIA World Factbook, 2000

- Belarus, by United States Department of State

- Belarusian diaspora

- History of Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- Miensk Voivodeship Officials of 16th-18th centuries

- Belarus 1994 Presidential Election

- Belarus history on the Official Website of the Republic of Belarus

- Belarusian Historical Review. Independent Academic Journal dedicated to history of Belarus (Belarusian and English versions)

- History of Belarus in five minutes. YouTube

_-_42.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)