Post-Brexit United Kingdom relations with the European Union

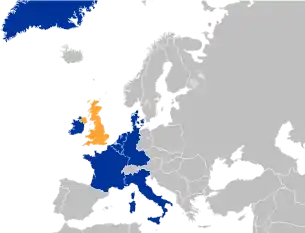

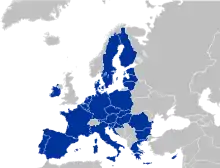

As of January 2021, the United Kingdom's post-Brexit relationship with the European Union and its members is governed by the Brexit withdrawal agreement and (provisionally, pending ratification) the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement. The latter was negotiated in 2020, and has been applied provisionally since 1 January 2021, but has not entered into force. The draft EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement needs the agreement of the European Parliament and Council of the European Union and the British Parliament. The latter gave its approval on 30 December 2020.

.svg.png.webp) | |

EU |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| European Union Delegation, London | United Kingdom Mission, Brussels |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador João Vale de Almeida | Ambassador Tim Barrow |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| UK membership of the European Union (1973-2020) |

|---|

|

|

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

|

|---|

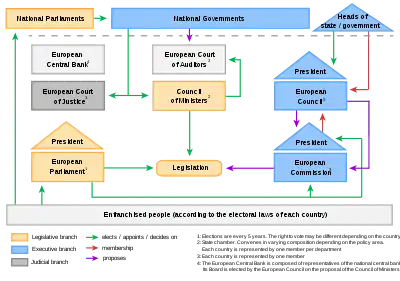

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

|

Following the UK's secession from the EU on 31 January 2020,[lower-alpha 1] the UK continued to conform to EU regulations and to participate in the EU Customs Union during a "Brexit transition period" that ended on 31 December 2020.

History

The Brexit transition period began on 1 February 2020, and ended on 31 December 2020. This allowed for a period of time to negotiate a bilateral trade agreement between the UK and the EU.

Trade

The UK has decided to withdraw from the single market, the customs union. Furthermore for all international agreements the EU entered into, the EU participation does not include the UK since 1 January 2021.[1]

Those definitive changes could create difficulties which might be under-estimated, according to Michel Barnier:[1]

- re-introduction of customs formalities, as was the case before UK membership, for every product imported and exported to and from the EU and the UK

- end of financial passporting rights for the UK services sector

- end of Community preference to all goods, trade and people from the UK in EU member states

- UK product certification will no longer be recognized within the EU

- imposition of non-tariff barriers to trade, such as the possibility of lengthy delays at the border, import quotas and immigration restrictions resulting from the loss of EU citizenship for UK workers

Post-Brexit negotiations have tried to create an ambitious pact between the UK and the EU to avoid disruption as much as possible, according to Michel Barnier.[1]

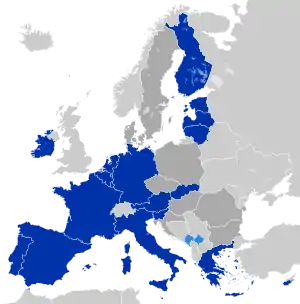

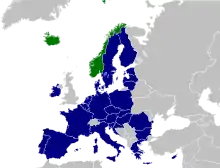

UK membership of the European Economic Area

The UK could have sought to continue to be a member of the European Economic Area, perhaps as a member of EFTA. In January 2017, Theresa May, the British Prime Minister, announced a 12-point plan of negotiating objectives and said that the UK government would not seek continued membership in the single market.[2][3]

WTO option

The no-deal WTO option would involve the United Kingdom ending the transition period without any trade agreement and relying on the most favoured nation trading rules set by the World Trade Organization.[4] The Confederation of British Industry said such a plan would be a "sledgehammer for our economy",[5][6][7] and the National Farmer's Union was also highly critical.[8] Positive forecasting for the effects of a WTO Brexit for the UK cite other countries' existing WTO trade with the EU and the benefits of repossessing full fishing rights for a maritime island nation.[9][10][11]

People

Immigration

The EEA Agreement and the agreement with Switzerland cover free movement of goods, and free movement of people.[12][13] Many supporters of Brexit want to restrict freedom of movement;[14] the Prime Minister ruled out any continuation of free movement in January 2017.[3]

Northern Ireland

One aspect of the final withdrawal agreement is the anomalous status of Northern Ireland.[15] The Northern Ireland Protocol that is part of the agreement provides (inter alia)

- Northern Ireland remains legally in the UK Customs Territory, and can be part of any future UK trade deals, as long as it is consistent with the Protocol. This results in a de jure customs border on the island of Ireland, between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.[16][17]

- Great Britain is no longer in a customs union with the European Union. Northern Ireland is also no longer legally in the EU Customs Union, but remains an entry point into it, creating a de facto customs border down the Irish Sea.[18][16][17]

- Level Playing Field provisions applying to Great Britain have been moved to the non-binding Political Declaration, although they are still present for Northern Ireland within the protocol.

- The UK needs to follow in respect of Northern Ireland EU regulations with regards to trade in goods, and also implement future changes of those regulations

- The Court of Justice has jurisdiction with regards to non-compliance of the UK with parts of the protocol as well as with the application of the trade in goods-regulation. Regarding the application of these rules courts can (and sometimes must) in regards to Northern Ireland make preliminary reference to the CJEU.

- EU tariffs (which ones are dependent on a UK–EU trade agreement), collected by the UK on behalf of the EU, would be levied on the goods going from Great Britain to Northern Ireland that would be "at risk" of then being transported into and sold in the Republic of Ireland; if they ultimately are not, then firms in Northern Ireland could claim rebates on goods where the UK had lower tariffs than the EU. A joint EU–UK committee will decide which goods are deemed "at risk".[18][17]

- A unilateral exit mechanism by which Northern Ireland can leave the protocol: the Northern Ireland Assembly will vote every four years on whether to continue with these arrangements, for which a simple majority is required. If the Assembly is suspended at the time, arrangements will be made so that the MLAs can vote. If the Assembly expresses cross-community support in one of these periodic votes, then the protocol will apply for the next eight years instead of the usual four. If the Assembly votes against continuing with these arrangements, then there will be a two-year period for the UK and EU to agree to new arrangements, with recommendations made by a joint UK–EU committee.[18][17] Rather than being a fallback position like the backstop was intended to be, this new protocol will be the initial position of Northern Ireland for at least the first four years after the transition period ends in December 2020.[15]

According to Michel Barnier, this might raise issues for Northern Irish companies which need the UK to deliver clarity on this topic.[1]

A joint EU–UK committee, headed by Michael Gove,[19] Minister for the Cabinet Office, and Maroš Šefčovič, a Vice-President of the European Commission,[1] oversees the operation of the arrangement.

See also

References

- "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission.

- Wilkinson, Michael (17 January 2017). "Theresa May confirms Britain will leave Single Market as she sets out 12-point Brexit plan". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 January 2017. (pay wall)

- "The government's negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM speech". gov.uk. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- LeaveHQ. "What's wrong with the WTO Option?". leavehq.com.

- O'Carroll, Lisa; Boffey, Daniel (13 March 2019). "UK will cut most tariffs to zero in event of no-deal Brexit". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- Glaze, Ben; Bloom, Dan; Owen, Cathy (13 March 2019). "Car prices to rise by £1,500 as no-deal tariffs are revealed". walesonline. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "No-deal tariff regime would be 'sledgehammer' to UK economy, CBI warns". Aol.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "This is why farmers are suddenly very worried about a no-deal Brexit". The Independent. 13 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- "Battle lines being drawn over fishing rights". February 27, 2020 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Britain, Briefings For. "The benefits of a WTO deal". Briefings For Britain.

- Davis, Charlotte (January 25, 2019). "'No problem with WTO!' Brexiteer MASTERFULLY dismantles no deal Brexit scare stories". Express.co.uk.

- "Free Movement of Capital", EFTA.int Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "Free Movement of Persons", EFTA.int Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Grose, Thomas. "Anger at Immigration Fuels the UK's Brexit Movement", U.S. News & World Report, Washington, D.C., 16 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Lisa O'Carroll (17 October 2019). "How is Boris Johnson's Brexit deal different from Theresa May's?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "Brexit: EU and UK reach deal but DUP refuses support". BBC News. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Parker, George; Brunsden, Jim (11 October 2019). "How Boris Johnson moved to break the Brexit deadlock". Financial Times. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "Brexit: What is in Boris Johnson's new deal with the EU?". BBC News. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "Prime Minister confirms ministerial leads for UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement Joint Committee". GOV.UK. 1 March 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.