List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

This article lists incidents that have been termed ethnic cleansing by some academic or legal experts. Not all experts agree on every case, particularly since there are a variety of definitions for the term ethnic cleansing. Where claims of ethnic cleansing originate from non-experts (e.g. journalists or politicians) this is noted.

Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern periods

- c. 146 BC: The Battle of Carthage was the main engagement of the Third Punic War between the Punic city of Carthage in what is now the country of Tunisia and the Roman Republic. It was a siege operation, starting sometime between 149 and 148 BC, and ending in the spring of 146 BC with the sack and complete destruction of the city of Carthage. In the spring of 146 BC, the Romans broke through the city wall, eventually after hours upon hours of house-to-house fighting, the Carthaginians surrendered. An estimated 50,000 surviving inhabitants were sold into slavery. The city was then leveled. The land surrounding Carthage was eventually declared ager publicus (public land), and it was shared between local farmers, and Roman and Italian ones.

- c. 350 AD: Ancient Chinese texts record that General Ran Min ordered the extermination of the Wu Hu, especially the Jie people, during the Wei–Jie war in the fourth century AD. People with racial characteristics such as high-bridged noses and bushy beards were killed; in total, 200,000 were reportedly massacred.[1]

- c. 1282 Sicilian Vespers (Italian: Vespri siciliani; Sicilian: Vespiri siciliani) is the name given to the successful rebellion on the island of Sicily that broke out on the Easter of 1282 against the rule of the French/Capetian king Charles I, who had ruled the Kingdom of Sicily since 1266. Within six weeks, three thousand French men and women were slain by the rebels, and the government of King Charles lost control of the island. It was the beginning of the War of the Sicilian Vespers.

Expulsions of Jews in Europe from 1100 to 1600

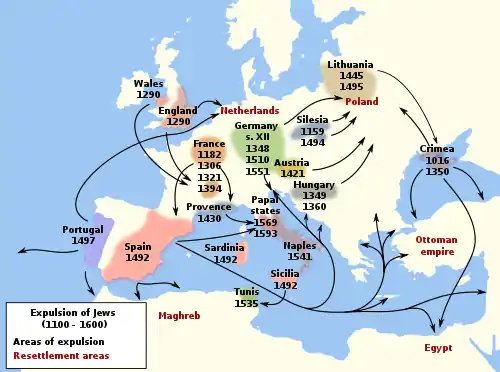

Expulsions of Jews in Europe from 1100 to 1600 - c. 1290 AD: Edward I of England expelled all Jews living in England in 1290. Hundreds of Jewish elders were executed.[2]

- c. 1250–1500 AD: From the 13th to the 16th centuries many European countries expelled the Jews from their territory on at least 15 occasions. Spain was preceded by England, France and some German states, among many others, and succeeded by at least five more expulsions.

- c. 1492–1614 AD: As a result of religious persecution, up to a quarter million Jews in Spain converted to Catholicism, those who refused (between 40,000 and 70,000) were expelled in 1492 following the Alhambra Decree. Many of the converts continued practising Judaism in secret, leading to the Inquisition. Shortly after the practice of Islam was outlawed and all of Spain's Muslims became nominally Christian.[3] The descendants of these converted Muslims were called Moriscos. After the 1571 suppression of the Morisco Revolt in the Alpujarras region, almost 80,000 Moriscos were relocated to other parts of Spain and some 270 villages and hamlets were repopulated with settlers brought from other regions. This was followed by a general Expulsion of the Moriscos between 1609–1614 which was nominally applied to the entire Spanish realm, but was carried out most thoroughly in the eastern region of Valencia. Although its overall success in terms of implementation is subject to academic debate and did not involve widespread violence, it is considered one of the first episodes of state-sponsored ethnic cleansing in the modern western world.

- 1556–1620: Plantations of Ireland. Land in Laois, Offaly, Munster and parts of Ulster was seized by the English crown and colonised with English settlers.[4] Ireland has been described as a "testing ground" for British colonialism, with the confiscation of land and expulsion of native Irish from their homelands being a rehearsal for the expulsion of the Native Americans by British settlers.[5]

- c. 1652 AD: After the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland and Act of Settlement in 1652, the whole post-war Cromwellian settlement of Ireland has been characterised by historians such as Mark Levene and Alan Axelrod as ethnic cleansing, in that it sought to remove Irish Catholics from the eastern part of the country, but others such as the historian Tim Pat Coogan have described the actions of Cromwell and his subordinates as genocide.[6]

- 1755–1764 AD: During the French and Indian War, the Nova Scotia colonial government, aided by New England troops, instituted a systematic removal of the French Catholic Acadian population of Nova Scotia – eventually removing thousands of settlers from the region and relocating them to areas in the Thirteen Colonies, Britain and France. Many eventually moved and settled in Louisiana and became known as Cajuns. Many scholars have described the subsequent death of over 50% of the deported Acadian population as an ethnic cleansing.[7]

19th century

- Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the first ruler of an independent Haiti, ordered the killing of the remaining white population of French creoles on Haiti by instigating the 1804 Haiti Massacre.[8]

- On 26 May 1830, president Andrew Jackson of the United States signed the Indian Removal Act which resulted in the Trail of Tears.[9][10][11][12]

- Michael Mann, basing his figures on those provided by Justin McCarthy, states that between 1821 and 1922, a large number of Muslims were expelled from Southeast Europe as Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia gained their independence from the Ottoman Empire. Mann describes these events as "murderous ethnic cleansing on a stupendous scale not previously seen in Europe". These countries sought to expand their territory against the Ottoman Empire, which culminated in the Balkan Wars of the early 20th century.[13] After each Russo-Turkish War, the Russians engaged in ethnic cleansing in the Caucasus.[14] After the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78) some 750,000 Ottoman Muslims disappeared from their native places.[15][16] Some 210,000–310,000 civilian Bulgarians were slaughtered[17][18] during the same war and the Bulgarian Horrors in 1876, and 100,000 fled.[19] In the previous Russo-Turkish Wars as a result of voluntary migration and ethnic cleansing an emigrant community of Bessarabian Bulgarians was formed. Some 200,000 Bulgarians had emigrated from the Ottoman Empire between 1768 and 1812,[20] until 1870 another 400,000 Bulgarians emigrated, mainly prompted by terror and ethnic cleansing in Thrace, while 200,000 were killed.[21] Partly as a result of ethnic cleansing some 250,000 Bulgarians immigrated to Bulgaria from the Ottoman Empire between 1878–1912.[22]

- In 2005, the historian Gary Clayton Anderson of the University of Oklahoma published The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1830–1875. This book repudiates traditional historians, such as Walter Prescott Webb and Rupert N. Richardson, who viewed the settlement of Texas by the displacement of the native populations as a healthful development. Anderson writes that at the time of the outbreak of the American Civil War, when the population of Texas was nearly 600,000, the still-new state was "a very violent place. ... Texans mostly blamed Indians for the violence – an unfair indictment, since a series of terrible droughts had virtually incapacitated the Plains Indians, making them incapable of extended warfare."[23] The Conquest of Texas was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

- The nomadic Roma people have been expelled from European countries several times.[24]

- Russian Empire was subject of several cases of ethnic and religious cleansing against minorities, specially Catholics (Polish and Lithuanians) Jews (Pale of Settlement) and Muslims.[25] The heaviest event was the Circassian genocide in 1872.

- From 1894–1896, in an effort to islamize the Ottoman Empire, Sultan Abdul Hamid II ordered the killing of ethnic Armenians (along with other Christian minorities) living in the Ottoman Empire, based on their religion. These killings later became known as the Hamidian massacres, named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II. It has been estimated that the total number of people killed ranges from 80,000 to 300,000.

- Beginning from about 1848, and extending into the 20th century, the residents of Silesia have been expelled by various governments as their homeland has come under the rule of different states.[26]

20th century

1900s–1910s

- The Herero and Namaqua genocide was a campaign of racial extermination and collective punishment that the German Empire undertook in German South West Africa (modern-day Namibia) against the Herero, Nama and San people. It is considered the first genocide of the 20th century.[27][28][29][30] It took place between 1904 and 1907 during the Herero Wars.

- During the Balkan Wars ethnic cleansings were carried out in Kosovo, Macedonia, Sanjak and Thrace, at first directed against the Muslim population, but later extended towards Christians, involving villages burnt and people massacred.[31] The Bulgarians, Serbs and Greeks burned villages and massacred civilians of Turks, although Turkish majority areas in Bulgarian-occupied areas have still remained almost unchanged.[32][33] The Turks usually massacred the male population of Bulgarians and Greeks they reoccupied, but not the Greeks during the Second Balkan War, the women and children were also raped in each massacre and frequently slaughtered.[34] During the Second Balkan War, an ethnic cleansing campaign carried out by the Ottoman Army and Turkish Bashi-bazouks exterminated the whole Bulgarian population of Ottoman Adrianople Vilayet (estimated 300,000 before the war) by either killing (60,000) or displacement.[35] Bulgarian Macedonians under Greek occupation were subjected to persecution, involving expulsion towards north of the Bulgarian border. The Bulgarians had expelled 100,000 Greeks from Macedonia and West Thrace before the territories have ultimately been returned to Greece.[36]Massacres of Albanians in the Balkan Wars killed 25,000 of them. 18,000 Bulgarian civilians were killed in Macedonia, whereas in Greek Macedonia a quarter of the previous Muslim and Bulgarian population remained. In addition to the dead, the aftermath counts 890,000 people who permanently left their homes, of which 400,000 fled to Turkey, 170,000 to Greece, 150,000[37] or 280,000 to Bulgaria.[38] The population size of Bulgarians in Macedonia was mostly reduced by forceful assimilation campaigns through terror, following the ban of the use of the Bulgarian language and declarations named "Declare yourself a Serb or die.", signers were required to renounce their Bulgarian identity on paper in Serbia and Greece.[33][34]

- The Pontian genocide was an ethnic cleansing carried out by the Turks against the Greek Orthodox population of the Pontus mountains. Approximately 353,000 ethnic Greeks were killed via mass deportation and many forced to leave their homes.

- The Bolshevik regime killed or deported an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Don Cossacks during the Russian Civil War, in 1919–1920.[39] Geoffrey Hosking stated "It could be argued that the Red policy towards the Don Cossacks amounted to ethnic cleansing. It was short-lived, however, and soon abandoned because it did not fit with normal Leninist theory and practice".[40]

- The Armenian Genocide took place both during and after World War I and it was implemented in two phases: the wholesale killing of the able-bodied male population through massacre and forced labor, and the deportation of women, children, the elderly and infirm on death marches to the Syrian Desert.[41][42] The total number of people killed as a result of the genocide is most commonly reported to be 1.5 million,[43][44][45] however, estimates range from 800,000 to 1,800,000.[46][47][48][49]

- In the course of several Armenian-Azerbaijani conflicts (1905–07, 1918–20), hundreds of thousands of Armenians and Azerbaijanis were resettled by force and/or many of them were killed and injured.[50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

1920s–1930s

- The Iraqi army launches a campaign against Assyrian villages in northern Iraq with the help of Kurdish and Arab tribes. The number of deaths ranged from 600–3,000. Around one third of the Assyrians later sought refuge in Syria.[60]

- During 1920–21, The Greek army in the Yalova-Gemlik Peninsula burned dozens of Turkish/Muslim villages with large scale violence and ethnic cleansing[61]

- The Population exchange between Greece and Turkey has been described as ethnic cleansing[62] In 1928 there were 1,104,216 Ottoman refugees in Greece.[63] 400,000 Muslims left Greece. The Greek genocide refers to 450,000–750,000 victims.

Greek refugees from Smyrna, 1922

- Second Sino-Japanese War, in which the Imperial Japanese Army invaded China in the 1930s. Millions of Chinese were killed, civilians and military personnel alike. The Three Alls Policy that was used by the Imperial Japanese Army resulted in the deaths of many of these Chinese. The Three Alls Policy was Kill all, Burn all, Seize all.

- Pacification of Libya, Italian authorities committed ethnic cleansing in the Cyrenaica region of Libya by forcibly removing and relocating 100,000 people of the Cyrenaican indigenous population from their valuable land property that was slated to be given to Italian settlers.[64]

- The Chinese Kuomintang Generals Ma Qi and Ma Bufang launched campaigns of expulsion in Qinghai and Tibet against ethnic Tibetans. The actions of these Generals have been called Genocidal by some authors.[65]

- However, that was not the last Labrang saw of General Ma. Ma Qi launched a war against the Tibetan Ngoloks, which author Dinesh Lal calls "genocidal", in 1928, inflicting a defeat upon them and seizing the Labrang Buddhist monastery. The Muslim forces looted and ravaged the monastery again.[66]

- Authors Uradyn Erden Bulag called the events that follow genocidal and David Goodman called them ethnic cleansing: The Republic of China government supported Ma Bufang when he launched seven extermination expeditions into Golog, eliminating thousands of Tibetans.[67] Some Tibetans counted the number of times he attacked them, remembering the seventh attack which made life impossible.[68] Ma was highly anti-communist, and he and his army wiped out many Tibetans in the northeast and eastern Qinghai, and also destroyed Tibetan Buddhist Temples.[69][70][71]

- The Holodomor (1932–1933) is considered by many historians as a genocidal famine perpetrated on the orders of Josef Stalin that involved widespread ethnic cleansing of ethnic Ukrainians in Soviet Ukraine. Food and grain were forcibly seized from villages, internal borders between Soviet Ukraine and the Russian SSR were sealed to prevent population movement; movement was also restricted between villages and urban centers. Stalin's destruction of ethnic Ukrainians also extended to a wide-scale purge of Ukrainian intelligentsia, political elite and Party officials before and after the famine. A ban on the Ukrainian language[72][73] and widespread Russification was also instilled.[73] An estimated 2.5 to 8 million Ukrainians were exterminated in the famine. After liquidation, Stalin repopulated the territory with ethnic Russians.[74]

- The Mexican Repatriation from 1929–1936 in which mass deportations of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans occurred due to nativist fears caused by the Great Depression in the United States. An estimated sixty percent of the 400,000 to 2 million deported were birthright U.S. citizens.[75][76] Because the forced movement was partially based on race, and frequently ignored citizenship, the process arguably meets modern definitions of ethnic cleansing.[77]

1940s

- The Generalplan Ost by Nazi Germany, the massacre of almost all East European Jews, most Gypsies, millions of Russian prisoners of war, very large number of Polish civilians, unknown but huge number of Russians, Byelorussians and Ukrainians in the German-occupied territories. It also resulted in millions of death in German extermination camps and the forced relocation of many civilians as to resettle German citizens into Eastern Europe [78] [79]

- The World War II casualties of the Soviet Union

- The Population transfers in the Soviet Union

- The Expulsion of Poles by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union following the defeat of Poland in the September Campaign

- The deportation of Romanians from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina (1940–1941, 1944–1951), by the USSR to Siberia and Central Asia.

- The Deportation of the Crimean Tatars on 18 May 1944 to the Uzbek SSR and other parts of the Soviet Union.

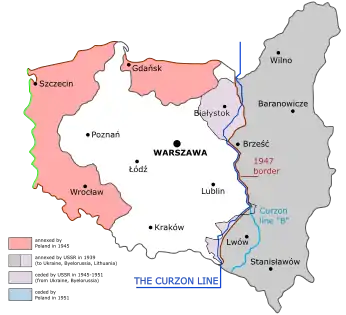

- The expulsion of 14 million ethnic Germans from the Former eastern territories of Germany after World War II. This policy was decided at the Potsdam Conference by the victorious powers.[80][81][82]

- The Nazi German government's persecutions and expulsions of Jews in Germany, Austria and other Nazi-controlled areas prior to the initiation of mass genocide. The estimated number of those who died in the process is approximately 6 million Jews.[83]

- At least 330,000 Serbs, 30,000 Jews and 30,000 Roma, and 12,000 Croats and Bosniaks were killed during the NDH (see Jasenovac concentration camp) (today Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina).[84][85] The same number of Serbs were forced out of the NDH, from May 1941 to May 1945. The Croatian Fascist regime managed to kill more than 45 000 Serbs, 12 000 or more Jews and approximately 16,000 Roma at the Jasenovac Concentration Camp.[86][87]

- Chetnik atrocities against Bosniaks and Croats in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1941–1945 have been characterised as organised ethnic cleansing. It is estimated that around 32,000 Croats (20,000 from Croatia, and 12,000 from Bosnia) and 33,000 Bosniaks were killed.[88][89]

- At least 40,000 Hungarian civilians were killed by Serbians in Vojvodina in an act of revenge (the so-called "Cold Days"), in 1944.[90]

Massacres of Poles in Volhynia in 1943. Most Poles of Volhynia (now in Ukraine) had either been murdered or had fled the area.

- During World War II, in Kosovo & Metohija, approximately 10,000 Serbs were killed by Nazi German soldiers and Albanian collaborators,[91][92] and about 80[91] to 100,000[91][93] or more[92] were ethnically cleansed.[93] After World War II, the new communist authorities of Yugoslavia banned Serbians and Montenegrins expelled during the war from returning to their abandoned estates.[94]

- During the four years of wartime occupation from 1941–1944, the Axis (German, Hungarian and NDH) forces committed numerous war crimes against the civilian population of Serbs, Roma and Jews in the former Yugoslavia: about 50,000 people in Vojvodina (north Serbia) (see Occupation of Vojvodina, 1941–1944) were murdered and about 280,000 were arrested, raped or tortured.[95] The total number of people killed under Hungarian occupation in Bačka was 19,573, in Banat 7,513 (under German occupation) and in Syrmia 28,199 (under Croatian occupation).[96]

- During the Axis occupation of Albania (1943–1944), the Albanian collaborationist organization Balli Kombëtar with Nazi German support mounted a major offensive in southern Albania (Northern Epirus) with devastating results: over 200 Greek populated towns and villages were burned down or destroyed, 2,000 ethnic Greeks were killed, 5,000 imprisoned and 2,000 forced to concentration camps. Moreover, 30,000 people had to flee to nearby Greece during and after this period.[97][98]

- Towards the end of World War II, nearly 14,000–25,000 ethnic Albanian Muslims were expelled from the coastal region of Epirus in northwestern Greece, an area known among Albanians as Chameria.

- During the Partition of India 6 million Muslims fled ethnic violence taking place in India to settle in what became Pakistan (and by 1971, Bangladesh) and 5 million Hindus and Sikhs fled from what became Pakistan and Bangladesh, to settle in India. The events which occurred during this time period have been described as ethnic cleansing by Ishtiaq Ahmed[99][100] and by Barbara and Thomas R. Metcalf.[101]

- In 1947, the Jammu Massacre took place. The event has been described as ethnic cleansing of Muslims in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir.[102][103][104] The ethnic cleansing took place at the orders of Maharaja Hari Singh. Hari Singh's army and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) were the perpetrators of ethnic cleansing. Around 70,000[102] to 300,000 Muslims were killed in the ethnic cleansing. The motive of ethnic cleansing was to change demographic of the Jammu region which was a Muslim majority area. As a result, Muslims were reduced to minority in the area with many either killed or fled to Pakistan administered Kashmir.[102][104]

- After the Republic of Indonesia achieved independence from the Netherlands in 1949, around 300,000 people, predominantly Indos, or people of mixed Indonesian and Dutch ancestry, fled or were expelled.[105]

- In the aftermath of the 1949 Durban Riots (an inter-racial conflict between Zulus and Asians in South Africa), hundreds of Indians fled Cato Manor.[106]

- In Ethiopia the Harari Muslims peacefully protested against religious oppression, however the state responded violently. Hundreds were arrested and the entire town of Harar was put under house arrest.[107] The government also took control of many assets and estates belonging to the people.[108] These events broke the Harari control of the city of Harar and 10,000 Hararis left the city.[109]

- Mario Roatta's war on the ethnic Slovene civil population in the Province of Ljubljana during Fascist Italy's occupation of Yugoslavia in accord with the 1920s speech by Benito Mussolini's speech:

When dealing with such a race as Slavic – inferior and barbarian – we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy.... We should not be afraid of new victims.... The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps.... I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians....

- Foibe massacres against Italians

- In 1948, approximately 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled[113] during the Palestine war. The event became known as the Palestinian exodus or the "Nakba" (catastrophe). Simultaneously, 850,000 Jews were expelled from the Arab world.[114]

1950s

- On 5 and 6 September 1955 the Istanbul Pogrom or "Septembrianá"/"Σεπτεμβριανά", secretly backed by the Turkish government, was launched against the Greek population of Istanbul. The mob also attacked some Jewish and Armenian residents of the city. The event contributed greatly to the gradual extinction of the Greek minority in the city and throughout the entire country, which numbered 100,000 in 1924 after the Turko-Greek population exchange treaty. By 2006 there were only 2,500 Greeks living in Istanbul.[115]

1960s

- On 5 July 1960, five days after the Congo gained independence from Belgium, the Force Publique garrison near Léopoldville mutinied against its white officers and attacked numerous European targets. This caused fear amongst the approximately 100,000 whites still resident in the Congo and led to their mass exodus from the country.[116]

- Ne Win's rise to power in 1962 and his relentless persecution of "resident aliens" (immigrant groups not recognised as citizens of the Union of Burma) led to an exodus of some 300,000 Burmese Indians. They migrated to escape racial discrimination and wholesale nationalisation of private enterprises a few years later in 1964.[117][118]

- As the FLN fought for the independence of Algeria from France, it expelled the pied-noir population of European descent and Jews; most fled to France, where they had citizenship. In just a few months in 1962, 900,000 of these European descendants and native Jewish people left the country.[119]

- Zanzibar expelled Arabs and Indians from the nation in 1964.[120][121]

- In 1966, there was unrest in the northern part of Nigeria that led to the death of about 80,000 people. Those killed were originally from the South Eastern region of the country and this act was seen as an attack on the Igbo people. This led C. Odumegwu Ojukwu, the military governor of the Eastern region, to declare that region a Sovereign state, Biafra. The Nigerian Civil War began on 6 July 1967, but ended in 1970 with the help of the United Kingdom and China. Although there is relative peace in Nigeria, today, there is still some religious unrest in the North being caused by the Boko Haram group.

- The expulsion of the Chagossians from the Chagos Archipelago by the United Kingdom, at the request of the United States in order to establish a military base, started in 1968 and concluded in 1973.[122][123]

1970s

- Shortly after Muammar Gaddafi gained power in Libya, the Libyan government forcibly expelled some 150,000 Italians living in the country on 7 October 1970, in retaliation for Italy's 1911 colonization of the country. The expulsion is known in Libya as the "Day of Vengeance".[124]

- During the Bangladesh War of Independence of 1971, the military of Pakistan carried out genocide killing between 300,000 and 3 million people and around 10 million Bengalis, mainly Hindus, fled the country. Additionally, many died in the poorly and hastily setup refugee camps in India. Furthermore, many intellectuals and other religious minorities were targeted by death squads and razakars. Thousands of temples were desecrated and thousands of women were raped.[125]

- Idi Amin's regime forced the expulsion in 1972 of Uganda's entire ethnic Asian population, mostly of Indian descent.[126]

- There was an ethnic cleansing of the Greek population of the areas under Turkish military occupation in Cyprus in 1974–76 during and after the Turkish Invasion of Cyprus. This has been the subject of litigation in the European Court of Human Rights in cases including Loizidou v. Turkey and the European Court of Justice in cases like Apostolides v Orams.[127][128][129]

- Following the U.S. withdrawal from South Vietnam in 1973 and the communist victory two years later, the Kingdom of Laos's coalition government was overthrown by the communists. The Hmong people, who had actively supported the anti-communist government, became targets of retaliation and persecution. The government of Laos has been accused of committing genocide against the Hmong,[130][131] with up to 100,000 killed.[132]

- The Communist Khmer Rouge government in Cambodia disproportionately targeted ethnic minority groups, including ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese and Thais. In the late 1960s, an estimated 425,000 ethnic Chinese lived in Cambodia; by 1984, as a result of Khmer Rouge genocide and emigration, only about 61,400 Chinese remained in the country. The small Thai minority along the border was almost completely exterminated, only a few thousand managing to reach safety in Thailand. The Cham Muslims suffered serious purges with as much as 80% of their population exterminated. The Khmer's racial supremacist ideology was responsible to this ethnic purge. A Khmer Rouge order stated that henceforth "The Cham nation no longer exists on Kampuchean soil belonging to the Khmers" (U.N. Doc. A.34/569 at 9).[133][134]

- Subsequent waves of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya fled Burma and many refugees inundated neighbouring Bangladesh including 250,000 in 1978 as a result of the King Dragon operation in Arakan.[135][136]

- The Sino-Vietnamese War resulted in the discrimination and consequent migration of Vietnam's ethnic Chinese. Many of these people fled as "boat people".[137] In 1978–79, some 250,000 ethnic Chinese left Vietnam by boat as refugees (many officially encouraged and assisted) or were expelled across the land border with China.[138][139]

1980s

- In 1983, in Sri Lanka, there were anti-Tamil riots targeting Tamil businessmen in Colombo.

- In the aftermath of Indira Gandhi's assassination in 1984, the ruling party Indian National Congress supporters formed large mobs and killed around 3000 Sikhs around Delhi in what is known as the 1984 anti-Sikh riots during the next four days. The mobs acting with the support of ruling party leaders used the Election voting list to identify Sikhs and kill them.

- In the 1987 and 1988 Al-Anfal Campaign, the Iraqi government under Saddam Hussein and headed by Ali Hassan al-Majid launched Al-Anfal against Kurdish civilians in Northern Iraq. The Iraqi government Massacred 100,000 to 182,000 non-combatant civilians including women and children, and destroyed about 4,000 villages (out of 4,655) in Iraqi Kurdistan. Between April 1987 and August 1988, 250 towns and villages were exposed to chemical weapons, 1,754 schools were destroyed, along with 270 hospitals, 2,450 mosques, 27 churches; and around 90% of all Kurdish villages in the targeted areas were wiped out.

- Between 16–17 March 1988, the Iraqi government under Saddam Hussein carried out a poison gas attack in the Kurdish town of Halabja in Iraqi Kurdistan. Between 3,200 and 5,000 civilians died instantly, and between 7,000 and 10,000 civilians were injured, and thousands more would die in the following years from complications, diseases, and birth defects caused by the attack.

- The forced assimilation campaign during 1984–1985 directed against ethnic Turks by the Bulgarian State resulted in the mass emigration of some 360,000 Bulgarian Turks to Turkey in 1989 has been characterized as ethnic cleansing.[140][141][142]

- The Nagorno Karabakh conflict has resulted in the displacement of populations from both sides. Among the displaced are 700,000 Azerbaijanis and several Kurds from ethnic Armenian-controlled territories including Armenia and areas of Nagorno-Karabakh,[143] more than 353,000 Armenians were forced to flee from territories controlled by Azerbaijan plus some 80,000 had to flee Armenian border territories.[144]

- Since April 1989, some 70,000 black Mauritanians – members of the Fula, Toucouleur, Wolof, Soninke and Bambara ethnic groups – have been expelled from Mauritania by the Mauritanian government.[145]

- In 1989, after bloody pogroms against the Meskhetian Turks by Uzbeks in Central Asia's Ferghana Valley, nearly 90,000 Meskhetian Turks left Uzbekistan.[146][147]

1990s

The cemetery at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial and Cemetery to Genocide Victims

Bhutanese refugees in Nepal

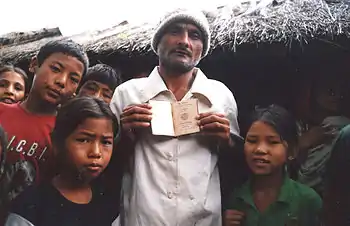

- In 1990, inter-ethnic tensions escalated in Bhutan, resulting in the flight of many Lhotshampa, or ethnic Nepalis, from Bhutan to Nepal, many of whom were expelled by the Bhutanese military. By 1996, over 100,000 Bhutanese refugees were living in refugee camps in Nepal. Many have since been resettled in Western nations.[148] One reason for this expulsion was the desire of the Bhutanese government to remove a largely Hindu population and preserve its Buddhist culture and identity.[149]

- In 1991, as part of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, during Operation Ring, Soviet troops and the predominantly Azerbaijani soldiers in the AzSSR OMON and army forcibly uprooted Armenians living in the 24 villages strewn across Shahumyan to leave their homes and settle elsewhere in Nagorno-Karabakh or in the neighboring Armenian SSR.[150] Human rights organizations documented a wide number of human rights violations and abuses committed by Soviet and Azerbaijani forces and many of them properly characterised them as ethnic cleansing. These violations and abuses included forced deportations of civilians, unlawful killings, torture, kidnapping harassment, rape and the wanton seizure or destruction of property.[151][152][153][154][155][156] Despite fierce protests, no measures were taken either to prevent the human rights abuses or to punish the perpetrators.[154] Approximately 17,000 Armenians living in twenty-three of Shahumyan's villages were deported out of the region.[157]

- In 1991, following a crackdown on Rohingya Muslims in Burma, 250,000 refugees took shelter in the Cox's Bazar district of neighboring Bangladesh.[158]

- After the Gulf War in 1991, Kuwait conducted a campaign of expulsion against the Palestinians living in the country, who before the war had numbered 400,000. Some 200,000 who had fled during the Iraqi occupation were banned from returning, while the remaining 200,000 were pressured into leaving by the authorities, who conducted a campaign of terror, violence, and economic pressure to get them to leave.[159] The Palestinians expelled from Kuwait moved to Jordan, where they had citizenship.[160] The policy which partly led to this exodus was a response to the alignment of PLO leader Yasser Arafat with Saddam Hussein.

- As a result of the 1991–1992 South Ossetia War, about 100,000 ethnic Ossetians fled South Ossetia and Georgia proper, most across the border into North Ossetia. A further 23,000 ethnic Georgians fled South Ossetia and settled in other parts of Georgia.[161]

- According to Helsinki Watch, the campaign of ethnic-cleansing was orchestrated by the Ossetian militants, during the events of the Ossetian–Ingush conflict, which resulted in the expulsion of approximately 60,000 Ingush inhabitants from Prigorodny District.[162]

Ethnic cleansing of a Croatian home

- The widespread ethnic cleansing accompanying the Croatian War of Independence that was committed by Serb-led Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and rebel militia in the occupied areas of Croatia (self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina) (1991–1995). Large numbers of Croats and non-Serbs were removed, either by murder, deportation or by being forced to flee. According to the ICTY indictment against Slobodan Milošević, there was an expulsion of around 170,000 to 250,000 Croats and other non-Serbs from their home, [163] [164] in addition to an estimated 10,000 Croats that were also killed.[165] Also, around 10,000 Croats left Vojvodina in 1992 due to persecution by Serb nationalists.[166] Milan Martić,[167] Milan Babić[168] and Vojislav Šešelj[169][170] were convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for persecution on racial, ethnic or religious ground, deportation and/or forcible displacement as a crime against humanity.

- In February 1992, hundreds of ethnic Azeris[171] and Meskhetian Turks[172] are massacred as Armenian troops capture the city of Khojaly in Nagorno-Karabakh.[173]

- Widespread ethnic cleansing accompanied the War in Bosnia (1992–1995). Large numbers of Croats and Bosniaks were forced to flee their homes by the Army of the Republika Srpska, large numbers of Serbs and Bosniaks by the Croatian Defence Council and Serbs and Croats by the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[174] Beginning in 1991, political upheavals in the Balkans displaced about 2,700,000 people by mid-1992, of which over 700,000 sought asylum in other parts of Europe.[175][176] In September 1994, UNHCR representatives estimated around 80,000 non-Serbs out of 837,000 who initially lived on the Serb-controlled territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina before the war remained there; an estimated removal of 90% of the Bosniak and Croat inhabitants of Serb-coveted territory, almost all of whom were deliberately forced out of their homes.[177] It also includes ethnic cleansing of non-Croats in the breakaway state the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia[178] The ICTY convicted several officials for persecution, forced transfer and/or deportation, including Momčilo Krajišnik,[179] Radoslav Brđanin,[180] Stojan Župljanin, Mićo Stanišić,[181] Biljana Plavšić,[182] Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić.[183]

An elderly Serb refugee in a tractor trailer leaving her home during Operation Storm

An elderly Serb refugee in a tractor trailer leaving her home during Operation Storm - Exodus of between 100,000 and 200,000 Krajina Serbs during and after the Croatian Army's Operation Storm.[184][185][186] Some investigators and academics describe this event as ethnic cleansing.[187][188][189][190] Historian Marko Attila Hoare disagrees that the operation was an act of ethnic cleansing, and points out that the Krajina Serb leadership evacuated the civilian population as a response to the Croatian offensive; whatever their intentions, the Croatians never had the chance to organise their removal.[191] [192] The ICTY indicted Croatian generals Ante Gotovina, Ivan Čermak and Mladen Markač for war crimes for their roles in the operation, charging them with participating in a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) aimed at the permanent removal of Serbs from the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) held part of Croatia. Gotovina and Markač were convicted and Čermak was acquitted in April 2011.[193] In November 2012, the ICTY Appeals Chamber acquitted Gotovina and Markač, reversing its earlier judgement by a 3–2 decision.[194] The Appeals Chamber ruled that there was insufficient evidence to conclude the existence of a joint criminal enterprise to remove Serb civilians by force and further stated that while the Croatian Army and Special Police committed crimes after the artillery assault, the state and military leadership could not be held responsible for their planning and creation.[195]

Kosovo Albanian refugees in 1999

- At least 700,000 Kosovo Albanians were deported from Kosovo between 1998 and 1999 during the Kosovo War.[196] The ICTY convicted several officials for persecution, forced displacement and/or deportation, including Nikola Šainović, Dragoljub Ojdanić and Nebojša Pavković.[197]

- In the aftermath of Kosovo War between 200,000 and 250,000 Serbs and other non-Albanians fled Kosovo.[198][199][200]

- The forced displacement and ethnic-cleansing of more than 250,000 people, mostly Georgians but some others too, from Abkhazia during the conflict and after in 1993 and 1998.[201]

- The mass expulsion of southern Lhotshampas (Bhutanese of Nepalese origin) by the northern Druk majority in Bhutan in 1990.[202] The number of refugees is approximately 103,000.[203]

- In October 1990, the militant Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), forcibly expelled the entire Muslim population (approx 65,000) from the Northern Province of Sri Lanka. The Muslims were given 48 hours to vacate the premises of their homes while their properties were subsequently looted by LTTE. Those who refused to leave were killed. This act of ethnic cleansing was carried out so the LTTE could facilitate their goal of creating a mono-ethnic Tamil state in Northern Sri Lanka.[204]

- In Jammu and Kashmir, a separatist insurgency has targeted the Hindu Kashmiri Pandit minority and 400,000 have been displaced, and 1,200 have been killed since 1991. Islamic terrorists infiltrated the region in 1989 and began an ethnic cleansing campaign to convert Kashmir to a Muslim state. Since that time, over 400,000 Kashmiri Hindus have either been murdered or forced from their homes.[205] This has been condemned and labeled as ethnic cleansing in a 2006 resolution passed by the United States Congress.[206] Also in 2009 the Oregon Legislative Assembly introduced a resolution to recognize 14 September 2007, as Martyrs Day to acknowledge the ethnic cleansing and the campaigns of terror inflicted on the non-Muslim minorities of Jammu and Kashmir by militants seeking to establish an independent Kashmir, and also to recognize the region as Indian territory rather than as a disputed territory – the resolution failed to pass.[207]

- The Jakarta riots of May 1998 targeted many Chinese Indonesians. Suffering from looting and arson many Chinese Indonesians fled from Indonesia.[208][209]

- There have been serious outbreaks of inter-ethnic violence on the island of Kalimantan since 1997, involving the indigenous Dayak peoples and immigrants from the island of Madura. In 2001 in the Central Kalimantan town of Sampit, at least 500 Madurese were killed and up to 100,000 Madurese were forced to flee. Some Madurese bodies were decapitated in a ritual reminiscent of the headhunting tradition of the Dayaks of old.[210]

21st century

2000s

- In 2003, Sinafasi Makelo, a representative of Mbuti Pygmies, told the UN's Indigenous People's Forum that during the Congo Civil War, his people were hunted down and eaten as though they were game animals. Both sides of the war regarded them as "subhuman" and some say their flesh can confer magical powers. Makelo asked the UN Security Council to recognise cannibalism as a crime against humanity and an act of genocide.[211][212]

- From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Indonesian paramilitaries organized and armed by Indonesian military and police killed or expelled large numbers of civilians in East Timor.[213][214][215][216][217][218][219] After the East Timorese people voted for independence in a 1999 referendum, Indonesian paramilitaries retaliated, murdering some supporters of independence and levelling most towns. More than 200,000 people either fled or were forcibly taken to Indonesia before East Timor achieved full independence.[220]

- Since the mid-1990s the central government of Botswana has been trying to move Bushmen out of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. As of October 2005, the government has resumed its policy of forcing all Bushmen off their lands in the Game Reserve, using armed police and threats of violence or death.[221] Many of the involuntarily displaced Bushmen live in squalid resettlement camps and some have resorted to prostitution and alcoholism, while about 250 others remain or have surreptitiously returned to the Kalahari to resume their independent lifestyle.[222] "How can we continue to have Stone Age creatures in an age of computers?" asked Botswana's president Festus Mogae.[223][224]

- Since 2003, Sudan has been accused of carrying out a campaign against several black ethnic groups in Darfur, in response to a rebellion by Africans alleging mistreatment. Sudanese irregular militia known as the Janjaweed and Sudanese military and police forces have killed an estimated 450,000, expelled around two million, and burned 800 villages.[225][226][227][228] A 14 July 2007 article notes that in the past two months up to 75,000 Arabs from Chad and Niger crossed the border into Darfur. Most have been relocated by the Sudanese government to former villages of displaced non-Arab people. Some 450,000 have been killed and 2.5 million have now been forced to flee to refugee camps in Chad after their homes and villages were destroyed.[229] Sudan refuses to allow their return, or to allow United Nations peacekeepers into Darfur.

- At least one additional thousand Serbs fled their homes during the 2004 unrest in Kosovo and numerous religious and cultural object were burned down.[230][231]

- During the Iraq Civil War and consequent Iraqi insurgency (2011–present), entire neighborhoods in Baghdad are being ethnically cleansed by Shia and Sunni militias.[232][233] Some areas are being evacuated by every member of a particular group due to lack of security, moving into new areas because of fear of reprisal killings. As of 21 June 2007, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 2.2 million Iraqis had been displaced to neighboring countries, and 2 million were displaced internally, with nearly 100,000 Iraqis fleeing to Syria and Jordan each month.[234][235][236]

- Assyrian exodus from Iraq from 2003 until present is often described as ethnic cleansing. Although Iraqi Christians represent less than 5% of the total Iraqi population, they make up 40% of the refugees now living in nearby countries, according to UNHCR.[237][238] In the 16th century, Christians constituted half of Iraq's population."UNHCR | Iraq". Archived from the original on 29 November 2008.</ref> In 1987, the last Iraqi census counted 1.4 million Christians.[239] Following the 2003 invasion and the resultant growth of militant Islamism, Christians' total numbers slumped to about 500,000, of whom 250,000 live in Baghdad.[240] Furthermore, the Mandaean and Yazidi communities are at the risk of elimination due to the ongoing atrocities by Islamic extremists.[241][242] A 25 May 2007 article notes that in the past 7 months only 69 people from Iraq have been granted refugee status in the United States.[243]

- In October 2006, Niger announced that it would deport Arabs living in the Diffa region of eastern Niger to Chad.[244] This population numbered about 150,000.[245] Nigerien government forces forcibly rounded up Arabs in preparation for deportation, during which two girls died, reportedly after fleeing government forces, and three women suffered miscarriages. Niger's government eventually suspended the plan.[246][247]

- In 1950, the Karen had become the largest of 20 minority groups participating in an insurgency against the military dictatorship in Burma. The conflict continues as of 2008. In 2004, the BBC, citing aid agencies, estimates that up to 200,000 Karen have been driven from their homes during decades of war, with 120,000 more refugees from Burma, mostly Karen, living in refugee camps on the Thai side of the border. Many accuse the military government of Burma of ethnic cleansing.[248] As a result of the ongoing war in minority group areas more than two million people have fled Burma to Thailand.[249]

- Civil unrest in Kenya erupted in December 2007.[250] By 28 January 2008, the death toll from the violence was at around 800.[251] The United Nations estimated that as many as 600,000 people have been displaced.[252][253] A government spokesman claimed that Odinga's supporters were "engaging in ethnic cleansing".[254]

- The 2008 attacks on North Indians in Maharashtra began on 3 February 2008. Incidences of violence against North Indians and their property were reported in Mumbai, Pune, Aurangabad, Beed, Nashik, Amravati, Jalna and Latur. Nearly 25,000 North Indian workers fled Pune,[255][256] and another 15,000 fled Nashik in the wake of the attacks.[257][258]

- South Africa Ethnic Cleansing erupted on 11 May 2008 within three weeks 80 000 were displaced the death toll was 62, with 670 injured in the violence when South Africans ejected non-nationals in a nationwide ethnic cleansing/xenophobic outburst. The most affected foreigners have been Somalis, Ethiopians, Indians, Pakistanis, Zimbabweans and Mozambiqueans. Local South Africans have also been caught up in the violence. Refugee camps a mistake Arvin Gupta, a senior UNHCR protection officer, said the UNHCR did not agree with the City of Cape Town that those displaced by the violence should be held at camps across the city.[259] During the 2010 FIFA world cup, rumors were reported that xenophobic attacks will be commenced after the final. A few incidents occurred where foreign individuals were targeted, but the South African police claims that these attacks can not be classified as xenophobic attacks but rather as regular criminal activity in the townships. Elements of the South African Army were sent into the affected townships to assist the police in keeping order and preventing continued attacks.

- In August 2008, the 2008 South Ossetia war broke out when Georgia launched a military offensive against South Ossetian separatists, leading to military intervention by Russia, during which Georgian forces were expelled from the separatist territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. During the fighting, 15,000[260] ethnic Georgians living in South Ossetia were forced to flee to Georgia proper, and Ossetian militia burned their villages to prevent their return.

2010s

- Strategic demographic and cultural cleansing by the Sinhala Buddhist majority of the Muslim and Tamil minorities in Sri Lanka.[261]

Refugees of the fighting in the Central African Republic, 19 January 2014

- The killing of hundreds of ethnic Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan during the 2010 South Kyrgyzstan riots resulting in the flight of thousands of Uzbek refugees to Uzbekistan have been called ethnic cleansing by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and international media.[262][263]

- The black Libyan tribe of Tawergha town de-populated by Anti-Gaddafi forces following the Battle of Tawergha in 2011.

- Members of the Azusa 13 gang, associated with the Mexican Mafia, were accused of attempting a racial cleansing of African Americans in Azusa, California.[264]

- 2012 Rakhine State riots. An estimated 90,000 people have been displaced in the recent sectarian violence between Rohingya Muslims and Buddhists in Burma's western Rakhine State.[135][265]

- Approximately 400,000 people have been displaced in the 2012 Assam ethnic violence between indigenous Bodos and Bengali-speaking Muslims in Assam, India.[266]

- Sources inside the Syriac Orthodox Church have reported that an ongoing ethnic cleansing of Syrian Christians is being carried out by anti-government rebels.[267][268]

- Central African Republic conflict (2012–present).[269] More than 1 million have been internally displaced.

- 2013 Burma anti-Muslim riots[270]

- South Sudanese conflict (2013–present). More than 700,000 have been internally displaced. Part of Ethnic violence in South Sudan.

- In 2017 a new wave of government sanctioned ethnic cleansing[271] against Rohingya Muslims amounting to genocide[272] with thousands killed and many villages burned to the ground with their inhabitants executed has been reported in Myanmar.[273][274][272][275][276] Even children were reportedly beheaded or burned alive by the Myanmar military and buddhist vigilantes.[277][278][279]

- The ongoing Turkish occupation of northern Syria has seen ethnic cleansing of Kurds, Christians, Yazidis, and other minorities, especially in the Afrin District, where 150,000–300,000 Kurds were displaced. The Turkish state has been resettling Afrin with Arab Syrian refugees.[280][281]

References

- 《晉書·卷一百七》("Jìnshū Juǎn Yī Bǎi Qī") Jin Shu Original text 閔躬率趙人誅諸胡羯,無貴賤男女少長皆斬之,死者二十余萬,屍諸城外,悉為野犬豺狼所食。屯據四方者,所在承閔書誅之,于時高鼻多須至有濫死者半。(Mǐn gōng lǜ zhào rén zhū zhū hú jié, wú guìjiàn nánnǚ shǎo cháng jiē zhǎn zhī, sǐzhě èrshí yú wàn, shī zhūchéng wài, xī wéi yě quǎn cháiláng suǒ shí. Tún jù sìfāng zhě, suǒzài chéng mǐn shū zhū zhī, yú shí gāo bí duō xū zhì yǒu làn sǐzhě bàn.)

- Richards, Eric (2004). Britannia's children: emigration from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland since 1600. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 1-85285-441-3.

- A brief History of Ethnic Cleansing, by Andrew Bell-Fialkoff, p. 4

- Rogers, Joe (30 April 2018). From an Irish Market Town. Publishamerica Incorporated. ISBN 9781456043087 – via Google Books.

- Fasua, Tope (1 February 2011). Crushed!: Navigating Africa'S Tortuous Quest for Development – Myths and Realities. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781467891233 – via Google Books.

-

- Albert Breton (Editor, 1995). Nationalism and Rationality. Cambridge University Press 1995. Page 248. "Oliver Cromwell offered Irish Catholics a choice between genocide and forced mass population transfer"

- Ukrainian Quarterly. Ukrainian Society of America 1944. "Therefore, we are entitled to accuse the England of Oliver Cromwell of the genocide of the Irish civilian population.."

- David Norbrook (2000).Writing the English Republic: Poetry, Rhetoric and Politics, 1627–1660. Cambridge University Press. 2000. In interpreting Andrew Marvell's contemporarily expressed views on Cromwell Norbrook says; "He (Cromwell) laid the foundation for a ruthless programme of resettling the Irish Catholics which amounted to large scale ethnic cleansing.."

- Frances Stewart Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine (2000). War and Underdevelopment: Economic and Social Consequences of Conflict v. 1 (Queen Elizabeth House Series in Development Studies), Oxford University Press. 2000. p. 51 "Faced with the prospect of an Irish alliance with Charles II, Cromwell carried out a series of massacres to subdue the Irish. Then, once Cromwell had returned to England, the English Commissary, General Henry Ireton, adopted a deliberate policy of crop burning and starvation, which was responsible for the majority of an estimated 600,000 deaths out of a total Irish population of 1,400,000."

- Alan Axelrod (2002). Profiles in Leadership, Prentice-Hall. 2002. Page 122. "As a leader Cromwell was entirely unyielding. He was willing to act on his beliefs, even if this meant killing the king and perpetrating, against the Irish, something very nearly approaching genocide"

- Tim Pat Coogan (2002). The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace. ISBN 978-0-312-29418-2. p 6. "The massacres by Catholics of Protestants, which occurred in the religious wars of the 1640s, were magnified for propagandist purposes to justify Cromwell's subsequent genocide."

- Peter Berresford Ellis (2002). Eyewitness to Irish History, John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-26633-4. p. 108 "It was to be the justification for Cromwell's genocidal campaign and settlement."

- John Morrill (2003). Rewriting Cromwell – A Case of Deafening Silences, Canadian Journal of History. Dec 2003. "Of course, this has never been the Irish view of Cromwell.

Most Irish remember him as the man responsible for the mass slaughter of civilians at Drogheda and Wexford and as the agent of the greatest episode of ethnic cleansing ever attempted in Western Europe as, within a decade, the percentage of land possessed by Catholics born in Ireland dropped from sixty to twenty. In a decade, the ownership of two-fifths of the land mass was transferred from several thousand Irish Catholic landowners to British Protestants. The gap between Irish and the English views of the seventeenth-century conquest remains unbridgeable and is governed by G. K. Chesterton's mirthless epigram of 1917, that "it was a tragic necessity that the Irish should remember it; but it was far more tragic that the English forgot it." - James M Lutz Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Brenda J Lutz, (2004). Global Terrorism, Routledge: London, p.193: "The draconian laws applied by Oliver Cromwell in Ireland were an early version of ethnic cleansing. The Catholic Irish were to be expelled to the northwestern areas of the island. Relocation rather than extermination was the goal."

- Mark Levene (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: Volume 2. ISBN 978-1-84511-057-4 Page 55, 56 & 57. A sample quote describes the Cromwellian campaign and settlement as "a conscious attempt to reduce a distinct ethnic population".

- Mark Levene (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State, I.B. Tauris: London:

[The Act of Settlement of Ireland], and the parliamentary legislation which succeeded it the following year, is the nearest thing on paper in the English, and more broadly British, domestic record, to a programme of state-sanctioned and systematic ethnic cleansing of another people. The fact that it did not include 'total' genocide in its remit, or that it failed to put into practice the vast majority of its proposed expulsions, ultimately, however, says less about the lethal determination of its makers and more about the political, structural and financial weakness of the early modern English state.

- MACLEOD, KATIE. "The Unsaid of the Grand Dérangement: An Analysis of Outsider and Regional Interpretations of Acadian History". University of Victoria. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018.

- Girard, Philippe R. (2011). The Slaves Who Defeated Napoleon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence 1801–1804. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. pp. 319–322. ISBN 978-0-8173-1732-4.

- Robert E. Greenwood (2007). Outsourcing Culture: How American Culture has Changed From "We the People" Into a One World Government. Outskirts Press. p. 97.

- Rajiv Molhotra (2009). "American Exceptionalism and the Myth of the American Frontiers". In Rajani Kannepalli Kanth (ed.). The Challenge of Eurocentrism. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 180, 184, 189, 199.

- Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon (2008). Congress and the Emergence of Sectionalism. Ohio University Press. pp. 15, 141, 254.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Ben Kiernan (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. pp. 328, 330.

- Michael Mann, The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing, pp. 112–4, Cambridge, 2005 "... figures are derive[d] from McCarthy (1995: I 91, 162–4, 339), who is often viewed as a scholar on the Turkish side of the debate. Yet even if we reduce his figures by 50 percent, they would still horrify. He estimates that between 1812 and 1922 somewhere around 5½ million Muslims were driven out of Europe and 5 million more were killed or died of either disease or starvation while fleeing. ... In the final Balkan Wars of 1912–13 he estimates that 62 percent of all Muslims (27 percent dead, 35 percent refugees) disappeared from the lands conquered by Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria. This was murderous ethnic cleansing on a stupendous scale not previously seen in Europe, ..."

- Mihcael, Radu. Dangerous Neighborhood: Contemporary Issues in Turkey's Foreign Relations, p. 78

- Howard, Douglas Arthur (2001), The history of Turkey, p. 67

- Crampton, RJ (1997), A Concise History of Bulgaria, Cambridge University Press, p. 426, ISBN 0-521-56719-X.

- Crowe, D. (30 April 2016). A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia. Springer. ISBN 9781349606719 – via Google Books.

- Statistika (54 ed.). Indiana University. 2002. p. 35.

- Greene, Francis Vinton (1879). Report on the Russian Army and its Campaigns in Turkey in 1877–1878. D Appleton & Co. p. 204.

- Halil İnalcık; Suraiya Faroqhi; Donald Quataert (28 April 1997). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 650. ISBN 9780521574556.

- Statistika. 54. Indiana University. 2002.

- International Labour Office (1926). Refugees and Labour Conditions in Bulgaria. California University.

- The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land, 1830–1875. University of Oklahoma Press. 2005. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8061-3698-1. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Donald Kenrick, Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) Archived 24 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine pages xx–xxiv, Scarecrow, Lanham, 2007

- Lohr, Eric (2003). Nationalizing the Russian Empire. Harvard: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674010413.

- Kamusella, Tomasz. The Dynamics of the Policies of Ethnic Cleansing in Silesia in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Web open access Archived 24 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Steinmetz, George (Winter 2005). "The First Genocide of the 20th Century and its Postcolonial Afterlives: Germany and the Namibian Ovaherero". Journal of the International Institute. 12 (2).

- Dr Jürgen Zimmerer and Prof. Benyamin Neuberger. "HERERO AND NAMA GENOCIDE". The Combat Genocide Association.

- "Herero Revolt 1904–1907". South African History Online. March 2011.

- Staff Reporter (March 1998). "Herero genocide – the facts and the criticisms". Mail & Guardian – Africa's Best Read.

- Emran Qureshi, Michael A. Sells. The New Crusades: Constructing the Muslim Enemy, p. 180

- Downes. Targeting Civilians in War. Cornell University Press.

- Lieberman, Benjamin (16 December 2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 75, 61. ISBN 9781442230385.

- Mozjes, Paul. Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. p. 34, 35

- Stark, Laura (30 May 2016). Ethnologia Europaea vol. 46:1. ISBN 9788763544870.

- Richard J. Evans. The Third Reich at War: 1939–1945, p. 146

- Ther, Philip. The Dark Side of Nation-States: Ethnic Cleansing in Modern Europe, p. 61

- Knight, Robert. Ethnicity, Nationalism and the European Cold War, p. 96

- Kort, Michael (2001). The Soviet Colossus: History and Aftermath, p. 133. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-0396-9.

- Hosking, Geoffrey A. (2006). Rulers and Victims: The Russians in the Soviet Union. Harvard University Press. p. footnote 29. ISBN 0-674-02178-9. The footnote ends with a reference: Holquist, Peter (1997). "Conduct Merciless, Mass Terror Decossackization on the Don, 1919". Cahiers du Monde Russe : Russie, Empire Russe, Union Soviétique, États Indépendants. 38 (38): 127–162. doi:10.3406/cmr.1997.2486.

- "Armenia: The Survival of A Nation" by Christopher J. Walker, Croom Helm (Publisher) London 1980, pp. 200–203

- The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916: Documents Presented to Viscount Grey of Falloden by Viscount Bryce, James Bryce and Arnold Toynbee, Uncensored Edition. Ara Sarafian (ed.) Princeton, New Jersey: Gomidas Institute, 2000. ISBN 0-9535191-5-5, pp. 635–649

- "Tsitsernakaberd Memorial Complex". Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Kifner, John (7 December 2007). "Armenian Genocide of 1915: An Overview".The New York Times.

- "German MPs recognise Armenian 'genocide' amid Turkish fury". BBC News. 2 June 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- Auron, Yair (2000). The banality of indifference: Zionism & the Armenian genocide. Transaction. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7658-0881-3.

- Göçek, Fatma Müge (2015). Denial of violence : Ottoman past, Turkish present and collective violence against the Armenians, 1789–2009. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 019933420X.

- Forsythe, David P. (11 August 2009). Encyclopedia of human rights (Google Books). Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

- Chalk, Frank Robert; Jonassohn, Kurt (10 September 1990). The history and sociology of genocide: analyses and case studies. Institut montréalais des études sur le génocide. Yale University Press. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-0-300-04446-1.

- ""Черный сад": Глава 5. Ереван. Тайны Востока". BBC Russian. 8 July 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- De Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- Lowell W. Barrington (2006). After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial & Postcommunist States. USA: University of Michigan Press. pp. In late 1988, the entire Azerbaijani population (including Muslim Kurds) – some 167, 000 people – was kicked out of the Armenian SSR. In the process, dozens of people died due to isolated Armenian attacks and adverse conditions. This population transfer was partially in response to Armenians being forced out of Azerbaijan, but it was also the last phase of the gradual homogenization of the republic under Soviet rule. The population transfer was the latest, and not so "gentle", episode of ethnic cleansing that increased Armenia's homogenization from 90 percent to 98 percent. Nationalists, in collaboration with the Armenian state authorities, were responsible for this exodus. ISBN 0-472-06898-9.

- De Waal, Thomas. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8147-1945-7, p. 40

- Cornell, Svante E. Small nations and great powers: a study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus. London: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0-7007-1162-7. p. 82

- Remnick, David. "Hate Runs High in Soviet Union's Most Explosive Ethnic Feud." The Washington Post. 6 September 1989.

- Hosking, Geoffrey A. The First Socialist Society: A History of the Soviet Union from Within, 2nd ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993, p. 475.

- Kenez, Peter. A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 272.

- Azerbaijan: The status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and other minorities, report, 1993, INS Resource Informacion Center, p.10

- "Azerbaijan – history – geography".

- Makiya, K (1998) [1989], Republic of fear:the politics of modern Iraq, University of California Press, pp. 168–172, ISBN 978-0-520-21439-2

- url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6DF4dNEjenIC&pg=PA113&dq=Most+Christian+irregulars+involved+in+the+ethnic+cleansing+of+the+Gemlik%E2%80%93Yalova%E2%80%93+%CC%87Izmit+region&hl=nl&sa=X&ei=WXPtUf-kGsTStAb3-YBg&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Most%20Christian%20irregulars%20involved%20in%20the%20ethnic%20cleansing%20of%20the%20Gemlik%E2%80%93Yalova%E2%80%93%20%CC%87Izmit%20region&f=falsequote=Most Christian irregulars involved in the ethnic cleansing of the Gemlik–Yalova– ̇İzmit region

- Sassounian, Harut (28 June 2009). "Turkish Prime Minister Admits Ethnic Cleansing". Huffington Post.

- Geniki Statistiki Ypiresia tis Ellados (Statistical Annual of Greece), Statistia apotelesmata tis apografis sou plithysmou tis Ellados tis 15–16 Maiou 1928, pg.41. Athens: National Printing Office, 1930. Quoted in Kontogiorgi, Elisabeth (2006-08-17). Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia: The Forced Settlement of Refugees 1922–1930. Oxford University Press. pp. 96, footnote 56. ISBN 978-0-19-927896-1.

- Anthony L. Cardoza. Benito Mussolini: the first fascist. Pearson Longman, 2006 Pp. 109.

- Lahtinen, Anja (December 2010). "GOVERNANCE MATTERS – CHINA'S DEVELOPING WESTERN REGION WITH A FOCUS ON QINGHAI PROVINCE" (PDF). HELDA – Digital Repository of the University of Helsinki.

- Paul Kocot Nietupski (1999). Labrang: a Tibetan Buddhist monastery at the crossroads of four civilizations. Snow Lion Publications. p. 90. ISBN 1-55939-090-5. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 273. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Chung-kuo fu li hui, Zhongguo fu li hui (1961). China reconstructs, Volume 10. China Welfare Institute. p. 16. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- David S. G. Goodman (2004). China's campaign to "Open up the West": national, provincial, and local perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 0-521-61349-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Shail Mayaram (2009). The other global city. Taylor & Francis US. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-415-99194-0. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Shail Mayaram (2009). The other global city. Taylor & Francis US. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-415-99194-0. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Anna Alekseyenko, Taras Byk, Markiyan Datsyshyn, Volodymyr Hrytsutenko, Lubomyr Mysiv, Oleksandr Voroshylo. "Holodomor – Ukrainian Genocide in the Early 1930s" (PDF). un.mfa.gov.ua.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ilie, Alexandra. "Holodomor, the Ukrainian Holocaust?" (PDF). Social Science Open Access Repository.

- Melnyczuk Morgan, Lesa (2010). "'Remember the peasantry': A study of genocide, famine, and the Stalinist – Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine, 1932–33, as it was remembered by post-war immigrants in Western Australia who experienced it". University of Notre Dame Australia.

- Hoffman, Abraham (1 January 1974). Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation Pressures, 1929–1939. VNR AG. ISBN 9780816503667.

- Balderrama, Francisco E.; Rodriguez, Raymond (1 January 2006). Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s. UNM Press. ISBN 9780826339737.

- Johnson, Kevin (Fall 2005). "The Forgotten Repatriation of Persons of Mexican Ancestry and Lessons for the War on Terror". 26 (1). Davis, California: Pace Law Review.

- General Plan Ost. Retrieved on 2020-10-28.

- Codename, Operation General Plan Ost. Retrieved on 2020-10-28.

- Cambridge Journals Online – Central European History – Abstract – National Mythologies and Ethnic Cleansing: The Expulsion of Czechoslovak Germans in 1945. Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Cambridge Journals Online – The Review of Politics – Abstract – The Expulsion of the Germans from Hungary: A Study in Postwar Diplomacy. Journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Diasporas and Ethnic Migrants: Germany, Israel, and Post-Soviet Successor ... – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Naimark., Norman M. (2001). Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00994-3.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum about Jasenovac and Independent State of Croatia Archived 16 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Genocide and Resistance in Hitler's Bosnia: The Partisans and the Chetniks, 1941–1943 pp20

- www.utilis.biz, Utilis d.o.o., Zagreb. "JUSP Jasenovac – LIST OF INDIVIDUAL VICTIMS OF JASENOVAC CONCENTRATION CAMP". www.jusp-jasenovac.hr.

- JUSP Jasenovac – ENGLISH. Jusp-jasenovac.hr. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Geiger 2012, p. 86.

- Žerjavić 1995, pp. 556–557.

- Account Suspended. Hungarianhistory.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Serge Krizman, Maps of Yugoslavia at War, Washington 1943.

- ISBN 86-17-09287-4: Kosta Nikolić, Nikola Žutić, Momčilo Pavlović, Zorica Špadijer: Историја за трећи разред гимназије природно-математичког смера и четврти разред гимназије општег и друштвено-језичког смера, Belgrade, 2002, p. 182.

- Annexe I Archived 1 March 2003 at the Wayback Machine, by the Serbian Information Centre-London to a report of the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

- Orthodox Diocese of Raska and Prizren. Kosovo.net. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Enciklopedija Novog Sada, Sveska 5, Novi Sad, 1996 (page 196).

- Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996 (pages 42, 43).

- Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: Volume II: Albania in Occupation and War, 1939–45. Owen Pearson. I.B. Tauris, 2006. ISBN 1-84511-104-4.

- .Pyrrhus J. Ruches. Albania's captives Argonaut, 1965, p. 172 "The entire carnage, arson and imprisonment suffered by the hands of Balli Kombetar...schools burned".

- Partition India :: Twentieth century regional history :: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (March 2002). "The 1947 Partition of India: A Paradigm for Pathological Politics in India and Pakistan". Asian Ethnicity. 3 (1): 9–28. doi:10.1080/14631360120095847. S2CID 145811519. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Barbara D. Metcalf; Thomas R. Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of India (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0521682251.

The outcome, akin to what today is called 'ethnic cleansing', produced an Indian Punjab 60 per cent Hindu and 35 per cent Sikh, while the Pakistan Punjab became almost wholly Muslim.

- "A tale of two ethnic cleansing". Times of India. 18 January 2015.

- A.G. Noorani (13 September 2018). "Why Jammu erupts?". Frontline.

- "The killing fields of Jammu: How Muslims became minority in the region". Scroll.in. 10 July 2016.

- "WHKMLA : History of Indonesia, 1945–1949". www.zum.de.

- "Current Africa race riots like 1949 anti-Indian riots: minister", TheIndianStar.com

- Ibrahim, Abadir (8 December 2016). The Role of Civil Society in Africa's Quest for Democratization. Springer. p. 134. ISBN 9783319183831. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Muehlenbeck, Phil (2012). Religion and the Cold War: A Global Perspective. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780826518521. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Wehib, Ahmed (October 2015). History of Harar and Harari (PDF). Harari people regional state, culture, heritage and tourism bureau. p. 141. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Pirjevec, Jože (2008). "The Strategy of the Occupiers" (PDF). Resistance, Suffering, Hope: The Slovene Partisan Movement 1941–1945. p. 27. ISBN 978-961-6681-02-5.

- Verginella, Marta (2011). "Antislavizmo, rassizmo di frontiera?". Aut aut (in Italian). ISBN 978-88-6576-106-9.

- Santarelli, Enzo (1979). Scritti politici: di Benito Mussolini; Introduzione e cura di Enzo Santarelli (in Italian). p. 196.

- Pappe, Ilan (2012). "The State of Denial: The Nakba in the Israeli Zionist Landscape". In Loewenstein, Antony; Moor, Ahmed (eds.). After Zionism: One State for Israel and Palestine. London: Saqi Books. p. 23.

- "Jewish Refugees from Arab Countries". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "From "Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity" series of Human Rights Watch" Archived 7 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine Human Rights Watch, 2 July 2006.

- Trueman, Chris N. (26 May 2015). "The United Nations and the Congo". The History Learning Site. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Smith, Martin (1991). Burma – Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London, New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 43–44, 98, 56–57, 176. ISBN 0-86232-868-3.

- "Asians v. Asians". TIME. 17 July 1964.

- Laurenson, John (1 August 2006). "Pied-noirs breathe life back into Algerian tourism". Marketplace.org. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Independence for Zanzibar". Empire's Children. Channel 4. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008.

- Heartman, Adam (26 September 2006). "A Homemade Genocide". Who's Fault Is It?. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- Monaghan, Paul (23 April 2016). "Britain's shame: the ethnic cleansing of the Chagos Islands". Politicsfirst.org.uk. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Taylor, Ollie (15 July 2017). "The ethnic cleansing of the Chagos Islands". Medium.com. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- BBC NEWS | Africa | Libya cuts ties to mark Italy era. Bbc.co.uk (2005-10-27). Retrieved on 2013-07-18.

- "Bangladesh: The Demolition Of Ramana Kali Temple In March 1971". Asian Tribune. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- "1972: Asians given 90 days to leave Uganda". BBC News. 7 August 1972.

- Oeter, Stefan (2014). "Recognition and Non-Recognition with Regard to Seccesion". In Walter, Christian; von Ungern-Sternberg, Antje; Abushov, Kavus (eds.). Self-determination and Secession in International Law. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-870237-5.

The Turkish army engaged in an exercise of 'ethnic cleansing' and expulsed more or less all Greek Cypriots from the North with brute force.

- Ó Cathaoir, Brendan (20 July 2004). "Invasion 30 years ago still scars Cyprus". Irish Times.

The occupied area was ethnically cleansed of its Greek Cypriot population: about 142,000 people – 23 per cent of the island's population – were driven from their homes and became refugees in their own country.

- "'Ethnic cleansing', Cypriot style". The New York Times. 5 September 1992. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. "WGIP: Side event on the Hmong Lao, at the United Nations". Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- Jane Hamilton-Merritt, Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942–1992 (Indiana University Press, 1999), pp337-460

- Forced Back and Forgotten (Lawyers' Committee for Human Rights, 1989), p8.

- "Cambodia – Population". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- Cambodia – the Chinese. Library of Congress Country Studies.

- "Ethnic Cleansing in Myanmar". The New York Times. 12 July 2012.

- Peter Ford (12 June 2012). "Why deadly race riots could rattle Myanmar's fledgling reforms". The Christian Science Monitor.

- Vietnam – Hoa. Library of Congress Country Studies.

- Butterfield, Fox, "Hanoi Regime Reported Resolved to Oust Nearly All Ethnic Chinese", The New York Times, 12 July 1979.

- Kamm, Henry, "Vietnam Goes on Trial in Geneva Over its Refugees", The New York Times, 22 July 1979.

- Kamusella, Tomasz. 2018. Ethnic Cleansing During the Cold War: The Forgotten 1989 Expulsion of Turks from Communist Bulgaria (Ser: Routledge Studies in Modern European History). London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138480520.

- "Bulgaria MPs Move to Declare Revival Process as Ethnic Cleansing – Novinite.com – Sofia News Agency".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Парламентът осъжда възродителния процес

- "Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives" (PDF). Conciliation Resources. August 2011.

- De Waal, Black Garden, p. 285

- "Fair elections haunted by racial imbalance". IRIN. 5 March 2007.

- "Focus on Mesketian Turks". IRIN. 9 June 2005.

- Meskhetian Turk Communities around the World Archived 14 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld – Chronology for Lhotshampas in Bhutan".

- "Refugees warn of Bhutan's new tide of ethnic expulsions". The Guardian . 20 April 2008

- Gokhman, M. "Карабахская война", [The Karabakh War] Russkaya Misl. 29 November 1991.

- "Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh – Operation Ring". sumgait.info.

- Human Rights Watch. Bloodshed in the Caucasus. Escalation of the armed conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. 1992 p. 9

- Заключение Комитета ВС РСФСР по правам человека Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Москва. Дом Советов РСФСР Краснопресненская наб., д.2

- Доклад Правозащитного центра общества "Мемориал" НАРУШЕНИЯ ПРАВ ЧЕЛОВЕКА В ХОДЕ ПРОВЕДЕНИЯ ОПЕРАЦИЙ ВНУТРЕННИМИ ВОЙСКАМИ МВД СССР, СОВЕТСКОЙ АРМИЕЙ И МВД АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНА В РЯДЕ РАЙОНОВ АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНСКОЙ РЕСПУБЛИКИ В ПЕРИОД С КОНЦА АПРЕЛЯ ПО НАЧАЛО ИЮНЯ 1991 ГОДА

- Report by Professor Richard Wilson "On the Visit to the Armenian-Azerbaijani Border, May 25–29, 1991" Presented to the First International Sakharov Conference on Physics, Lebedev Institute, Moscow on 31 May 1991.

- Армянский Вестник № 18–19 (32–33) 1991-11 Archived 4 July 2013 at Archive.today

- Melkonian. My Brother's Road, p. 186.

- Burmese exiles in desperate conditions, BBC News

- Steven J. Rosen (2012). "Kuwait Expels Thousands of Palestinians". Middle East Quarterly.

From March to September 1991, about 200,000 Palestinians were expelled from the emirate in a systematic campaign of terror, violence, and economic pressure while another 200,000 who fled during the Iraqi occupation were denied return.

- Le Troquer, Yann; Al-Oudat, Rozenn Hommery (1999). "From Kuwait to Jordan: The Palestinians' Third Exodus". Journal of Palestine Studies. 28 (3): 37–51. doi:10.2307/2538306. JSTOR 2538306.

- Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, RUSSIA. THE INGUSH-OSSETIAN CONFLICT IN THE PRIGORODNYI REGION, May 1996.

- Russia: The Ingush-Ossetian Conflict in the Prigorodnyi Region (Paperback) by Human Rights Watch Helsinki Human Rights Watch (April 1996) ISBN 1-56432-165-7

- "Milosevic: Important New Charges on Croatia". Human Rights Watch. 21 October 2001. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.