Elections in New Zealand

New Zealand is a representative democracy.[1] Members of the unicameral New Zealand Parliament gain their seats through nationwide general elections, or in by-elections. General elections are usually held every three years; they may be held at an earlier date (a "snap" election) at the discretion of the prime minister (advising the governor-general), although it usually only happens in the event of a vote of no confidence or other exceptional circumstances. A by-election is held to fill a vacancy arising during a parliamentary term. The most recent general election took place on 17 October 2020.[2]

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of New Zealand |

| Constitution |

|

|

New Zealand has a multi-party system due to proportional representation. The introduction of the mixed-member proportional (MMP) voting system in 1993 was the most significant change to the electoral system in the 20th century.[1] The Electoral Commission is responsible for the administration of parliamentary elections.[3] The introduction of MMP has led to mostly minority or coalition governments, but the first party to win an outright majority since the introduction of MMP was the Labour Party, led by Jacinda Ardern, on the 17 October 2020.[4]

Local government politicians, including mayors, councillors and District Health Boards are voted in during the local elections, held every three years. These elections used both single transferable vote (STV) and first past the post (FPP) systems in 2007.[5]

Overview of elections

History

The first general and provincial elections in New Zealand took place in 1853, the year after the British Parliament passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. Women's suffrage was introduced in 1893, with New Zealand being the first modern country to do so.[6]

Initially, New Zealand used the first-past-the-post electoral system. The first election under the mixed-member proportional (MMP) system was held in 1996 following the 1993 electoral referendum.

Electoral roll

The electoral roll consists of a register of all enrolled voters, organised (primarily alphabetically by surname) within electorates. All persons who meet the requirements for voting must by law register on the electoral roll, even if they do not intend to vote. Although eligible voters must be enrolled, voting in New Zealand elections is not compulsory.[7]

To be eligible to enrol, a person must be 18 years or older, a New Zealand citizen or permanent resident and have lived in New Zealand for one or more years without leaving the country (with some exceptions).[8] People can provisionally enrol to vote once they turn 17, with them being automatically enrolled on their 18th birthday.

The Registrar of Births Deaths and Marriages automatically notifies a person's death to the Electoral Commission so they may be removed from the roll. Enrolment update drives are conducted prior to every local and general election in order to keep the roll up to date, identifying any voters who have failed to update their address or cannot be found.

The roll records the name, address and stated occupation of all voters, although individual electors can apply for "unpublished" status on the roll in special circumstances, such as when having their details printed in the electoral roll could threaten their personal safety. The roll is "public information" meaning it can be used for legitimate purposes such as selecting people for jury service but it can be abused especially by marketing companies who use the electoral roll to send registered voters unsolicited advertising mail. According to Elections New Zealand, "having the printed electoral rolls available for the public to view is a part of the open democratic process of New Zealand".[9] The Electoral Commission, in their report on the 2017 general election, recommended that roll sales be discontinued for anything other than electoral purposes.[10]

Electorates and lists

New Zealanders refer to electoral districts as "electorates", or more colloquially as "seats". Since the 2020 general election there are 72 electorates,[11] including seven Māori electorates reserved for people of Māori ethnicity or ancestry who choose to place themselves on a separate electoral roll.[12] All of New Zealand is covered by a general electorate and an overlapping Māori electorate. In terms of geography, electorates can have varying sizes as their boundaries are decided by the population living within the electorate.[11]

All electorates have roughly the same number of people in them; the Representation Commission periodically reviews and alters electorate boundaries to preserve this approximate balance. The number of people per electorate depends on the population of the South Island, which as the less populous of the country's two main islands has sixteen guaranteed electorates. Hence, the ideal number of people per electorate equals the population of the South Island divided by sixteen. From this, the Commission determines the number of North Island, Māori and list seats, which may fluctuate accordingly.[13] The number of electorates increased by one compared to the 2017 election to account for the North Island's higher population growth, creating Takanini; and the boundaries of 30 general electorates and five Māori electorates were adjusted.[14][15]

Supplementing the geographically-based electorate seats, the system currently allows for 49 at-large "list seats".[16] A nationwide "party vote" fills these seats from closed lists submitted by political parties; they serve to make a party's total share of seats in parliament reflect its share of the party vote. For example, if a party wins 20% of the party vote, but only ten electorate seats, it will win fourteen list-seats, so that it has a total of 24 seats: 20% of the 120 seats in parliament. (See Electoral system of New Zealand § MMP in New Zealand)

General elections

| Parliament | Election |

|---|---|

| 30th[nb 2] | 1 September 1951 |

| 31st | 13 November 1954 |

| 32nd | 30 November 1957 |

| 33rd | 26 November 1960 |

| 34th | 30 November 1963 |

| 35th | 26 November 1966 |

| 36th | 29 November 1969 |

| 37th | 25 November 1972 |

| 38th | 29 November 1975 |

| 39th | 25 November 1978 |

| 40th | 28 November 1981 |

| 41st[nb 3] | 14 July 1984 |

| 42nd | 15 August 1987 |

| 43rd | 27 October 1990 |

| 44th | 6 November 1993 |

| 45th[nb 4] | 12 October 1996 |

| 46th | 27 November 1999 |

| 47th[nb 5] | 27 July 2002 |

| 48th | 17 September 2005 |

| 49th | 8 November 2008 |

| 50th | 26 November 2011 |

| 51st | 20 September 2014 |

| 52nd | 23 September 2017 |

| 53rd | 17 October 2020 |

| Key | |

| Election held on last Saturday of November | |

| Footnotes | |

| |

New Zealand general elections generally occur every three years. Unlike some other countries, New Zealand has no fixed election-date for general elections, but rather the prime minister determines the timing of general elections by advising the governor-general when to issue the writs for a general election. The Constitution Act 1986 requires new parliamentary elections every three years, unless a major crisis arises or the prime minister loses the ability to command a majority in parliament.[17] The 1910s, 1930s and 1940s saw three elections delayed due to World War I, the Great Depression and World War II, respectively: the 1919, 1935 and 1943 elections would otherwise have taken place in 1917, 1934 and 1941 (Parliaments passed Acts extending their terms). Also, governments have occasionally called early, or "snap" elections (for example, in 1951 in the midst of an industrial dispute involving striking waterfront workers).[18]

The term of Parliament and the timing of general elections is set out in the Constitution Act 1986 and the Electoral Act 1993. Under section 19 of the Constitution Act, Parliament must meet within six weeks of the return of the writs for a general election, while under section 17, the term of Parliament ends three years after the return of the writs, unless Parliament is dissolved earlier by the governor-general.[19] Section 125 of the Electoral Act requires that whenever Parliament expires or is dissolved, the governor-general must issue a writ of election within seven days. Section 139 of the Electoral Act provides further constraints.[19] The writ must be returned within 50 days of being issued, though the governor-general may appoint an earlier return date in the writ itself. Furthermore, polling day must be between 20 and 27 days after the close of nominations. Thus, New Zealand law requires elections at least once every three years and two months, though elections are often held after three years, traditionally in November.[19] The extra two months allow for some flexibility when returning to a fourth-quarter election after an early election, as happened in 2005 and 2008 after the 2002 snap election.

Early or "snap" elections have occurred at least three times in New Zealand's history: in 1951, 1984 and 2002. Early elections often provoke controversy, as they potentially give governing parties an advantage over opposition candidates. Note that of the three elections in which the government won an increased majority, two involved snap elections (1951 and 2002 – the other incumbent-boosting election took place in 1938). The 1984 snap election backfired on the government of the day: many believe that the Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, called it while drunk.[20][21] The 1996 election took place slightly early (on 12 October) to avoid holding a by-election after the resignation of Michael Laws.

The prime minister's power to determine the election date can give the government some subtle advantages. For example, if governing parties believe that a section of the population will either vote against them or not at all, they might hold the election in early spring, when the weather may well keep less-committed voters away from the polls. Party strategists take the timing of important rugby union matches into account, partly because a major match in the same weekend of the election will likely lower voting-levels, and partly because of a widespread belief that incumbent governments benefit from a surge of national pride when the All Blacks (the New Zealand national rugby team) win and suffer when they lose.

Tradition associates elections with November – give or take a few weeks. After disruptions to the 36-month cycle, prime ministers tend to strive to restore it to a November base. In 1950, the legal requirement to hold elections on a Saturday was introduced,[22] and this first applied to the 1951 election. Beginning with the 1957 election, a convention was formed to hold general elections on the last Saturday of November. This convention was upset by Robert Muldoon calling a snap election in 1984. It took until the 1999 election to get back towards the convention, only for Helen Clark to call an early election in 2002. By the 2011 election, the conventional "last Saturday of November" was achieved again.[23] However, the convention was broken again for the 2014 and 2017 elections, which both occurred on the second-to-last Saturday in September.

Local elections

Unlike general elections, elections for the city, district and regional councils of New Zealand have a fixed election date. Under section 10 of the Local Electoral Act 2001,[24] elections must be held on the "second Saturday in October in every third year" from the date the Act came into effect in 2001. The latest local body elections were held on 12 October 2019.

Nomination and deposit of political parties and candidates

A party that has more than 500 fee-paying members may register with the Electorate Commission. Registered parties may submit a party list on payment of a $1000 deposit. This deposit is refunded if the party reaches 0.5% of the party votes. Electorate candidates may be nominated by a registered party or by two voters in that electorate. The deposit for an electorate candidate is $300 which is refunded if they reach 5%.

Voting

Elections always take place on a Saturday, so as to minimise the effect of work or religious commitments that could inhibit people from voting. Voting (the casting of ballots) happens at various polling stations, generally established in schools, church halls, sports clubs, or other such public places. Polling booths are also set up in hospitals and rest homes for use by patients. The 2005 election made use of 6,094 such polling stations. Voters may vote at any voting station in the country.[25]

Advance voting is available in the two weeks before election day. A dominating feature of the 2017 General Election was the increased use of advance voting. 47% of the votes were taken in advance and grew from 24% in the 2014 election.[10] In earlier elections, voters were required to provide reasons to vote in advance. From 2011 and beyond, voters could use this service for any reason. The Northcote by-election in 2018 was the first parliamentary election where more people voted in advance than on election day.[26]

If voters cannot physically get to a polling place, they may authorise another person to collect their ballot for them. Overseas voters may vote by mail, fax, internet or in person at New Zealand embassies or high commissions. Disabled voters can choose to vote via a telephone dictation service.

Voters are encouraged to bring with them the EasyVote card sent to them before each election, which specifies the voter's name, address, and position on the electoral roll (e.g. Christchurch East 338/23 means the voter is listed in the Christchurch East electorate roll, on line 23 of page 338). However, this is not required, voters may simply state their name and address to the official.

The voting process uses printed voting ballots. After the voting paper is issued, the voter goes behind a cardboard screen, where they mark their paper using a supplied orange ink pen. The voter then folds their paper and places in their electorate's sealed ballot box. Voters who enrol after the rolls have been printed, voting outside their electorate, or on the unpublished roll casts a "special vote" which is separated for later counting.

According to a survey commissioned by the Electoral Commission, 71% of voters voted in less than 5 minutes and 92% in less than 10 minutes. 98% of voters are satisfied with the waiting time.[27]

New Zealand has a strictly enforced election silence; campaigning is prohibited on election day.[28] All election advertisements must be removed or covered by midnight on the night before the election. Opinion polling is also illegal on election day.[28]

Local elections are by mail. Referenda held in conjunction with elections are held at polling stations, between elections may be done by mail or at polling stations at the government's discretion.

Voting in the MMP system

Each voter gets a party vote, where they choose a political party, and an electorate vote, where they vote for a candidate in their electorate. The party vote determines the proportion of seats assigned to each party in Parliament. Each elected candidate gets a seat, and the remaining seats are filled by the party from its party list.[29]

For example:

A party wins 30% of the party vote. Therefore, it will get 30% of the 120 seats in Parliament (roughly 36 seats). The party won 20 electorates through the electorate vote. Therefore, 20 of the 36 seats will be taken by the MPs that won their electorate, and 16 seats will be left over for the party to fill from their list of politicians.[29]

Vote-counting and announcement

Polling places close at 7.00pm on election day and each polling place counts the votes cast there. The process of counting the votes by hand begins with advance and early votes from 9:00am.[30] From 7.00pm, results (at this stage provisional ones) go to a central office in Wellington, for announcement as they arrive. Starting from 2002, a dedicated official website, "www.electionresults.govt.nz" has provided "live" election result updates. The provisional results from polling places and advance votes will generally become available from 7:30pm, with advance vote results usually released by 8:30pm and all results by midnight.

All voting papers, counterfoils and electoral rolls are returned to the respective electorate's returning officer for a mandatory recount. A master roll is compiled from the booth rolls to ensure no voter has voted more than once. Special and overseas votes are also included at this stage. The final count is usually completed in two weeks, occasionally producing surprise upsets. In 1999 the provisional result indicated that neither the Greens nor New Zealand First would qualify for Parliament, but both parties qualified on the strength of special votes, and the major parties ended up with fewer list seats than expected. The final results of the election become official when confirmed by the Chief Electoral Officer.

Candidates and parties have 3 working days after the release of the official results to apply for a judicial recount, either of individual electorates or of all electorates (a nationwide recount). A judicial recount takes place under the auspices of a District Court judge; a nationwide recount must take place under the auspices of the Chief District Court Judge.[31] At the 2011 election, recounts were requested in the Waitakere and Christchurch Central electorates, after the top two candidates in each were separated by less than 50 votes.

Referenda by mail are scanned into a computer system, but not counted until the close of polling. When the poll closes at 7.00pm, the scanned ballots are counted and the results announced soon after.

Results

General elections

The following table lists all previous general elections held in New Zealand (note that elections for Māori seats initially took place at different times from elections for general seats). The table displays the dates of the elections, the officially recorded voter turnout, and the number of seats in Parliament at the time.[32] On the right the table shows the number of seats won by the four most dominant parties in New Zealand's history (the Liberal Party and the Reform Party, which later merged to form the National Party, and the Labour Party), as well as the number won by other candidates (either independents or members of smaller political parties).

Bold indicates that the party was able to form a government.

| Term | Election | Date(s) | Official turnout | Total seats | Liberal | Reform | Labour | Others | Indep. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United | |||||||||

| National | |||||||||

| First past the post (FPP) | |||||||||

| 1st | 1853 election | 4 July – 1 October | No record | 37 | - | - | - | - | 37 |

| 2nd | 1855 election | 28 October – 28 December | No record | 37 | - | - | - | - | 37 |

| 3rd | 1860–1861 election | 12 December – 28 March | No record | 53 | - | - | - | - | 53 |

| 4th | 1866 election | 12 February – 6 April | No record | 70 | - | - | - | - | 70 |

| 5th | 1871 election | 14 January – 23 February | No record | 78 | - | - | - | - | 78 |

| 6th | 1875–1876 election | 30 December – 28 March | No record | 88 | - | - | - | - | 88 |

| 7th | 1879 election | 28 August – 15 September | 66.5% | 88 | - | - | - | - | 88 |

| 8th | 1881 election | 9 December | 66.5% | 95 | - | - | - | - | 95 |

| 9th | 1884 election | 22 June | 60.6% | 95 | - | - | - | - | 95 |

| 10th | 1887 election | 26 September | 67.1% | 95 | - | - | - | - | 95 |

| 11th | 1890 election | 5 December | 80.4% | 74 | 40 | - | - | 25 | 9 |

| 12th | 1893 election | 28 November | 75.3% | 74 | 51 | - | - | 13 | 10 |

| 13th | 1896 election | 4 December | 76.1% | 74 | 39 | - | - | 26 | 9 |

| 14th | 1899 election | 6 December | 77.6% | 74 | 49 | - | - | 19 | 6 |

| 15th | 1902 election | 25 November | 76.7% | 80 | 47 | - | - | 19 | 14 |

| 16th | 1905 election | 6 December | 83.3% | 80 | 58 | - | - | 18 | 4 |

| Two-round system period | |||||||||

| 17th | 1908 election | 17 November, 24 November, 1 December | 79.8% | 80 | 50 | - | 1 | 26 | 3 |

| 18th | 1911 election | 7 December, 14 December | 83.5% | 80 | 33[note 1] | 37 | 4 | - | 6 |

| Return to FPP | |||||||||

| 19th | 1914 election | 10 December | 84.7% | 80 | 33 | 41 | 5 | - | 1 |

| 20th | 1919 election | 17 December | 80.5% | 80 | 21 | 47 | 8 | - | 4 |

| 21st | 1922 election | 7 December | 88.7% | 80 | 22 | 37 | 17 | - | 4 |

| 22nd | 1925 election | 4 November | 90.9% | 80 | 11 | 55 | 12 | - | 2 |

| 23rd | 1928 election | 14 November | 88.1% | 80 | 27 | 27 | 19 | 1 | 6 |

| 24th | 1931 election | 2 December | 83.3% | 80 | 19[note 2] | 28[note 2] | 24 | 1 | 8 |

| 25th | 1935 election | 27 November | 90.8% | 80 | 7[note 2] | 9[note 2] | 53 | 4 | 7 |

| 26th | 1938 election | 15 October | 92.9% | 80 | 25 | 53 | - | 2 | |

| 27th | 1943 election | 25 September | 82.8% | 80 | 34 | 45 | - | 1 | |

| 28th | 1946 election | 27 November | 93.5% | 80 | 38 | 42 | - | - | |

| 29th | 1949 election | 30 November | 93.5% | 80 | 46 | 34 | - | - | |

| 30th | 1951 election | 1 September | 89.1% | 80 | 50 | 30 | - | - | |

| 31st | 1954 election | 13 November | 91.4% | 80 | 45 | 35 | - | - | |

| 32nd | 1957 election | 30 November | 92.9% | 80 | 39 | 41 | - | - | |

| 33rd | 1960 election | 26 November | 89.8% | 80 | 46 | 34 | - | - | |

| 34th | 1963 election | 30 November | 89.6% | 80 | 45 | 35 | - | - | |

| 35th | 1966 election | 26 November | 86.0% | 80 | 44 | 35 | 1 | - | |

| 36th | 1969 election | 29 November | 88.9% | 84 | 45 | 39 | - | - | |

| 37th | 1972 election | 25 November | 89.1% | 87 | 32 | 55 | - | - | |

| 38th | 1975 election | 29 November | 82.5% | 87 | 55 | 32 | - | - | |

| 39th | 1978 election | 25 November | 69.2%[note 3] | 92 | 51 | 40 | 1 | - | |

| 40th | 1981 election | 28 November | 91.4% | 92 | 47 | 43 | 2 | - | |

| 41st | 1984 election | 14 July | 93.7% | 95 | 37 | 56 | 2 | - | |

| 42nd | 1987 election | 15 August | 89.1% | 97 | 40 | 57 | - | - | |

| 43rd | 1990 election | 27 October | 85.2% | 97 | 67 | 29 | 1 | - | |

| 44th | 1993 election | 6 November | 85.2% | 99 | 50 | 45 | 4 | - | |

| MMP era | |||||||||

| 45th | 1996 election | 12 October | 88.3% | 120 | 44 | 37 | 39 | - | |

| 46th | 1999 election | 27 November | 84.1% | 120 | 39 | 49 | 32 | - | |

| 47th | 2002 election | 27 July | 77.0% | 120 | 27 | 52 | 41 | - | |

| 48th | 2005 election | 17 September | 80.9% | 121 | 48 | 50 | 23 | - | |

| 49th | 2008 election | 8 November | 78.69%[33] | 122 | 58 | 43 | 21 | - | |

| 50th | 2011 election | 26 November | 74.21% | 121 | 59 | 34 | 28 | - | |

| 51st | 2014 election | 20 September | 77.9% | 121 | 60 | 32 | 29 | - | |

| 52nd | 2017 election | 23 September | 79.8% | 120 | 56 | 46 | 18 | - | |

| 53rd | 2020 election | 17 October | 82.5% | 120 | 33 | 65 | 22 | - | |

- The Liberal Party lost their majority in the 1911 election; however, due to the lack of a majority, they were able to stay in power until a vote of no confidence resulted in the formation of the Reform Government in 1912.

- The United Party (a regrouping of the Liberals) and the Reform Party contested the 1931 and 1935 elections as a coalition, but did not formally merge as the National Party until 1936.

- Due to major problems with the enrolment process, commentators generally consider that the 1978 election had a significantly higher turnout than official figures indicate.[32]

By-elections

Local elections

Referendums

Ten referendums have been held so far. Seven were government-led, and three were indicative citizen "initiatives".

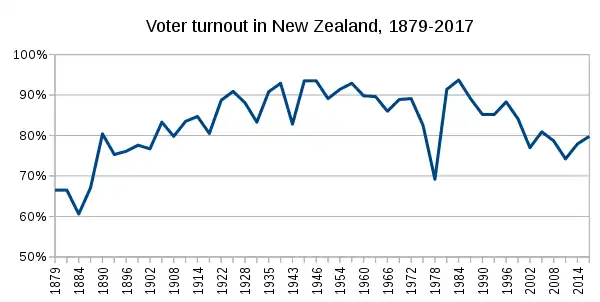

Voter turnout

As shown in the table above, voter turnout has generally declined in New Zealand general elections since the mid-20th century. Concerns about declining democratic engagement and participation have been raised by the Electoral Commission, and by commentators such as Sir Geoffrey Palmer and Andrew Butler, leading some to support the introduction of compulsory voting, as exists in Australia. A system of compulsory voting looks unlikely to manifest in the near future with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern arguing that it is an ineffective way to foster citizen engagement.[34]

In its report after the 2014 election, the Electoral Commission issued the following statement:

Turnout has been in decline in most developed democracies over the last 30 years, but New Zealand's decline has been particularly steep and persistent. At the 2011 election, turnout as a percentage of those eligible to enrol dropped to 69.57 per cent, the lowest recorded at a New Zealand Parliamentary election since the adoption of universal suffrage in 1893. The 2014 result, 72.14 per cent, is the second lowest. This small increase, while welcome, is no cause for comfort. New Zealand has a serious problem with declining voter participation.

Of particular concern has been the youth vote (referring to the group of voters aged 18–29), which has had significantly lower turnout than other age brackets. A graph published on the Electoral Commission's website demonstrates the lower turnout in younger age groups.[35] Those from poorer and less educated demographics also fail to vote at disproportionately high rates.[36]

Orange Guy

Orange Guy is the mascot used in electoral related advertising by the Electoral Commission.[37] He is an amorphous orange blob who usually takes on a human form, but can transform into any object as the situation warrants. His face is a smiley, and his chest sports the logo of the Electoral Commission. Since 2017 he has been voiced by stand-up comedian David Correos.[38] In the 2020 general election campaign, he was joined by a dog, Pup, who is also orange and resembes a cross between a Jack Russel Terrier and a Dachshund.[38]

Both the Electoral Commission logo and Orange Guy icon are trademarked to the Electoral Commission.

See also

References

- Palmer, Matthew (20 June 2012). "Constitution – Representative democracy and Parliament". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "2020 General Election". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "About the Electoral Commission". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Kiwi PM Jacinda Ardfern vows unity as she wins historic majority". The Australian. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "2007 Local Elections". Elections New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- "Votes for Women". www.elections.org.nz. Electoral Commission New Zealand. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Enrol to vote". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Archived 6 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Elections New Zealand, Enrolling – FAQ. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Elections New Zealand, Viewing the printed electoral rolls. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- "Electoral Commission Report on the 2017 General Election". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "What are electorates?". New Zealand Parliament. 17 April 2020.

- "Origins of the Māori seats". New Zealand Parliament. 31 May 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- "Number of electorates and electoral populations: 2018 Census". www.stats.govt.nz. Statistics New Zealand. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- Small, Zane (4 August 2020). "NZ Election 2020 electorate changes: Adjusted boundaries, new names". Newshub. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Boundary Review 2019/20". Elections.nz. Electoral Commission. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Electoral Commission. "Electoral Commission: Candidate And Party Lists Released". www.scoop.co.nz. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ""Term of Parliament," Section 17 of the Constitution Act 1986". Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- Bryce, Edwards (1 July 2016). "Elections and campaigns - Elections". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Parliament and the General Election" (PDF). parliament.nz. Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. August 2014. p. 4.

- "REHABILITATED: TOM SCOTT :: Salient". Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- "Sips causing political slips". Television New Zealand. 28 March 2001. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- "Key dates in New Zealand electoral reform". Elections New Zealand. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- James, Colin (14 June 2011). "John Key, modest constitutional innovator". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "Local Electoral Act 2001 No 35 (as at 24 January 2009), Public Act". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- "Electoral Commission". elections.org.nz. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Early voting in Northcote reaches new high". Radio New Zealand. 21 June 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Voter and non-voter satisfaction survey 2008". New Zealand Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Election Day Rules for Candidates, Parties and Third Parties". New Zealand Electoral Commission. 17 September 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "MMP Voting System". Electoral Commission New Zealand. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Electoral Act 1993, 174C – Preliminary count of early votes". Government of New Zealand Parliamentary Council Office. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- Sections 190 and 191, Electoral Act 1993

- "General elections 1853–2005 – dates & turnout". Elections New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- "Voter turnout not high despite record enrolment". NZPA. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- McCulloch, Craig. "Former PMs support compulsory voting in NZ". radionz.co.nz. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Voter Turnout Statistics". Electoral Commission. 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "Non-voters in 2008 and 2011 general elections". archivestats.org.nz. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "New Zealand's Famous 'Orange Guy' Gets a Makeover". Saatchi & Saatchi Asia Pacific. 23 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "How much for that doggy? Electoral Commission reveals the price of Pup and their 2020 brand makeover". TVNZ. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

Further reading

- McRobie, Alan (1989). New Zealand electoral atlas. Wellington: GP Books. ISBN 9780477013840.

- Gibbons, Matthew (2003). An annotated bibliography of New Zealand election programmes since 1905 (PDF). Hamilton, N.Z.: Dept. of Political Science and Public Policy at the University of Waikato. ISBN 9780473097714.

External links

- Electoral Commission website

- Official election results website

- New Zealand Election Study – analysis of elections by the University of Auckland

- Adam Carr's Election Archive