Geography of New Zealand

New Zealand (Māori: Aotearoa) is an island country located in the south-western Pacific Ocean, near the centre of the water hemisphere. It consists of a large number of islands, estimated around 600, mainly remnants of a larger land mass now beneath the sea. The two main islands by size are the North Island (or Te Ika-a-Māui) and the South Island (or Te Waipounamu), separated by the Cook Strait. The third-largest is Stewart Island (or Rakiura), located 30 kilometres (19 miles) off the tip of the South Island across Foveaux Strait. Other islands are significantly smaller in area. The three largest islands stretch 1,500 kilometres (930 miles) across latitudes 34° to 47° south.[1] New Zealand is the sixth-largest island country in the world, with a land size of 267,710 km2 (103,360 sq mi).[2]

New Zealand in the South Pacific Ocean | |

| Continent | Zealandia |

|---|---|

| Region | Oceania |

| Coordinates | 42°S 174°E |

| Area | Ranked 75th |

| • Total | 267,710 km2 (103,360 sq mi) |

| • Land | 97.9% |

| • Water | 2.1% |

| Coastline | 15,134 km (9,404 mi) |

| Borders | 0 km |

| Highest point | Aoraki / Mount Cook 3,724 m (12,218 ft) |

| Lowest point | Taieri Plain −2 m |

| Longest river | Waikato River 425 km (264 mi) |

| Largest lake | Lake Taupo 3,487 km2 (1,346 sq mi) |

| Climate | Mostly temperate, with some areas being tundra and subantarctic |

| Terrain | Mostly mountainous or steep hills, volcanic peaks in the central North Island, and fiords in the far south west. |

| Natural Hazards | Flooding, earthquakes, volcanic activity, tsunamis |

| Exclusive economic zone | 4,083,744 km2 (1,576,742 sq mi) |

New Zealand's terrain ranges from the fiord-like sounds of the southwest to the sandy beaches of the far north. The South Island is dominated by the Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana while a volcanic plateau covers much of the central North Island. Temperatures rarely fall below 0 °C or rise above 30 °C and conditions vary from wet and cold on the South Island's west coast to dry and continental a short distance away across the mountains and near subtropical in the northern reaches of the North Island.

About two-thirds of the land is economically useful, the remainder being mountainous. The vast majority of New Zealand's population lives on the North and South Islands. The largest urban area is Auckland, in the north of the North Island.

The country is situated about 2,000 kilometres (1,200 miles) south-east of the Australian mainland across the Tasman Sea,[3] the closest foreign neighbour to its main islands being Norfolk Island (Australia) about 750 kilometres (470 miles) to the north west. Other island groups to the north are New Caledonia, Tonga and Fiji. It is the southernmost nation in Oceania. The relative proximity of New Zealand north of Antarctica has made the South Island a gateway for scientific expeditions to the continent.

Physical geography

Overview

New Zealand is located in the South Pacific Ocean at 41°S 174°E, near the centre of the water hemisphere.[4] It is a long and narrow country, extending 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) along its north-north-east axis with a maximum width of 400 kilometres (250 mi).[5] The land size of 267,710 km2 (103,360 sq mi) makes it the sixth-largest island country.[2] New Zealand consists of a large number of islands, estimated around 600.[6] The islands give it 15,134 km (9,404 mi) of coastline and extensive marine resources. New Zealand claims the 9th largest exclusive economic zone in the world, covering 4,083,744 km2 (1,576,742 sq mi), more than 15 times its land area.[7]

The South Island is the largest land mass of New Zealand, and is the 12th-largest island in the world. The island is divided along its length by the Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana. The east side of the island has the Canterbury Plains while the West Coast is famous for its rough coastlines, high rainfall, very high proportion of native bush, and glaciers.[8]

The North Island is the second-largest island, and the 14th-largest in the world. It is separated from the South Island by the Cook Strait, with the shortest distance being 23 kilometres (14 mi).[9][10] The North Island is less mountainous than the South Island,[8] although a series of narrow mountain ranges form a roughly north-east belt that rises up to 1,700 metres (5,600 ft). Much of the surviving forest is located in this belt, and in other mountain areas and rolling hills.[11] The North Island has many isolated volcanic peaks.

Besides the North and South Islands, the five largest inhabited islands are Stewart Island (30 kilometres (19 mi) due south of the South Island), Chatham Island (some 800 kilometres (500 mi) east of the South Island),[12] Great Barrier Island (in the Hauraki Gulf),[13] D'Urville Island (in the Marlborough Sounds)[14] and Waiheke Island (about 22 km (14 mi) from central Auckland).[15]

Extreme points

The phrase "From Cape Reinga to The Bluff" is frequently used within New Zealand to refer to the extent of the whole country.[16] Cape Reinga / Te Rerenga Wairua is the northwesternmost tip of the Aupouri Peninsula, at the northern end of the North Island. Bluff is Invercargill's port, located near the southern tip of the South Island, below the 46th parallel south. However, the extreme points of New Zealand are actually located in several outlying islands.[17]

The points that are farther north, south, east or west than any other location in New Zealand are as follows:[17]

- The northernmost point is in Nugent Island in the Kermadec Islands (29.231667°S 177.869167°W).

- The southernmost point is Jacquemart Island in the Campbell Island group (52.619444°S 169.125833°E).

- The easternmost point is situated in a group of islands within the Chatham Islands called the Forty-Fours (43.963306°S 175.831410°W).

- The westernmost point is Cape Lovitt on Auckland Island (50.799838°S 165.870128°E).

Antipodes

New Zealand is largely antipodal to the Iberian Peninsula of Europe.[18] The northern half of the South Island corresponds to Galicia and northern Portugal.[18] Most of the North Island corresponds to central and southern Spain, from Valladolid (opposite the southern point of the North Island, Cape Palliser), through Madrid and Toledo to Cordoba (directly antipodal to Hamilton), Lorca (opposite East Cape), Málaga (Cape Colville), and Gibraltar. Parts of the Northland Peninsula oppose Morocco, with Whangārei nearly coincident with Tangiers. The antipodes of the Chatham Islands lie in France, just north of the city of Montpellier.[18] The Antipodes Islands were named for their supposed antipodal position to Britain; although they are the closest land to the true antipodes of Britain, their location 49°41′S 178°48′E is directly antipodal to a point a few kilometres to the east of Cherbourg on the north coast of France.[19]

In Europe the term "Antipodes" is often used to refer to New Zealand and Australia (and sometimes other South Pacific areas),[20] and "Antipodeans" to their inhabitants.

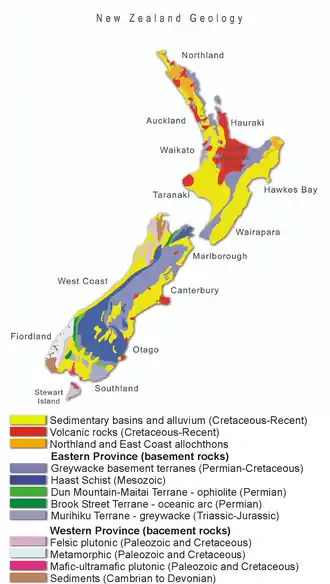

Geology

New Zealand is part of Zealandia, a microcontinent nearly half the size of Australia that gradually submerged after breaking away from the Gondwanan supercontinent.[21] Zealandia extends a significant distance east into the Pacific Ocean and south towards Antarctica. It also extends towards Australia in the north-west. This submerged continent is dotted with topographic highs that sometimes form islands. Some of these, such as the main islands (North and South), Stewart Island, New Caledonia, and the Chatham Islands, are settled. Other smaller islands are eco-sanctuaries with carefully controlled access.

The New Zealand land mass has been uplifted due to transpressional tectonics between the Indo-Australian Plate and Pacific plates (these two plates are grinding together with one riding up and over the other).[22] This is the cause of New Zealand's numerous earthquakes and volcanoes.

To the east of the North Island the Pacific Plate is forced under the Indo-Australian Plate. The North Island of New Zealand has widespread back-arc volcanism as a result of this subduction. There are many large volcanoes with relatively frequent eruptions. There are also several very large calderas, with the most obvious forming Lake Taupo. Taupo has a history of incredibly powerful eruptions, with the Oruanui eruption approx. 26,500 years ago ejecting 1,170 cubic kilometres (280 cubic miles) of material and causing the downward collapse of several hundred square kilometres to form the lake.[23] The last eruption occurred c. 180 CE and ejected at least 100 cubic kilometres of material, and has been correlated with red skies seen at the time in Rome and China.[24] The associated geothermal energy from this volcanic area is used in numerous hydrothermal power plants.[25] Some volcanic places are also famous tourist destinations, such as the Rotorua geysers.[26]

The subduction direction is reversed through the South Island, with the Indo-Australian Plate forced under the Pacific Plate. The transition between these two different styles of continental collision occurs through the top of the South Island. This area has significant uplift and many active faults; large earthquakes are frequent occurrences here. The most powerful in recent history, the M8.3 Wairarapa earthquake, occurred in 1855. This earthquake generated more than 6 metres (20 ft) of vertical uplift in places, and caused a localised tsunami. Fortunately casualties were low due to the sparse settlement of the region. In 2013, the area was rattled by the M6.5 Seddon earthquake, but this caused little damage and no injuries.[27] New Zealand's capital city, Wellington, is situated in the centre of this region.

The subduction of the Indo-Australian Plate drives rapid uplift in the centre of the South Island (approx. 10 millimetres (0.39 in) per year). This uplift forms the Southern Alps. These roughly divide the island, with a narrow wet strip to the west and wide and dry plains to the east. The resulting orographic rainfall enables the hydroelectric generation of most of the country's electricity.[28] A significant amount of the movement between the two plates is accommodated by lateral sliding of the Indo-Australian Plate north relative to the Pacific Plate. The plate boundary forms the nearly 800 kilometres (500 mi) long Alpine Fault. This fault has an estimated rupture reoccurrence interval of ~330 years, and last ruptured in 1717 along 400 kilometres (250 mi) of its length. It passes directly under many settlements on the West Coast of the South Island and shaking from a rupture would likely affect many cities and towns throughout the country.

The rapid uplift and high erosion rates within the Southern Alps combine to expose high grade greenschist to amphibolite facies rocks, including the gemstone pounamu (jade). Geologists visiting the West Coast can easily access high-grade metamorphic rocks and mylonites associated with the Alpine Fault, and in certain places can stand astride the fault trace of an active plate boundary.[29]

To the south of New Zealand the Indo-Australian Plate is subducting under the Pacific Plate, and this is beginning to result in back-arc volcanism. The youngest (geologically speaking) volcanism in the South Island occurred in this region, forming the Solander Islands (<2 million years old).[30] This region is dominated by the rugged and relatively untouched Fiordland, an area of flooded glacially carved valleys with little human settlement.[31]

Mountains, volcanoes and glaciers

The South Island is much more mountainous than the North, but shows fewer manifestations of recent volcanic activity. There are 18 peaks of more than 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) in the Southern Alps, which stretch for 500 kilometres (310 mi) down the South Island.[32] The closest mountains surpassing it in elevation are found not in Australia, but in New Guinea and Antarctica. As well as the towering peaks, the Southern Alps include huge glaciers such as Franz Josef and Fox.[33] The country's highest mountain is Aoraki / Mount Cook; its height since 2014 is listed as 3,724 metres (12,218 feet) (down from 3,764 m (12,349 ft) before December 1991, due to a rockslide and subsequent erosion).[34] The second highest peak is Mount Tasman, with a height of 3,497 metres (11,473 ft).[35]

The North Island Volcanic Plateau covers much of central North Island with volcanoes, lava plateaus, and crater lakes. The three highest volcanoes are Mount Ruapehu (2,797 metres (9,177 ft)), Mount Taranaki (2,518 metres (8,261 ft)) and Mount Ngauruhoe (2,287 metres (7,503 ft)). Ruapehu's major eruptions have historically been about 50 years apart,[36] in 1895, 1945 and 1995–1996. The 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera, located near Rotorua, was New Zealand's largest and deadliest eruption in the last 200 years, killing over 100 people.[37] Another long chain of mountains runs through the North Island, from Wellington to East Cape. The ranges include Tararua and Kaimanawa.[38]

The lower mountain slopes are covered in native forest. Above this are shrubs, and then tussock grasses. Alpine tundra consists of cushion plants and herbfields; many of these plants have white and yellow flowers.[39]

Caves

New Zealand's cave systems have three main origins, the chemical weathering of limestone by water (karst), lava caves and erosion by waves (sea caves). Therefore, the distribution of limestone, marble (metamorphosed limestone) and volcanoes defines the location of caves in inland New Zealand.[40] The main regions of karst topography are the Waitomo District[41] and Takaka Hill in the Tasman district. Other notable locations are on the West Coast (Punakaiki), the Hawkes Bay and Fiordland.[42]

Lava caves (lava tubes) usually form in pāhoehoe lava flows, which are less viscus and typical formed from basalt. When an eruption occurs the outer layer of the lava flow hardens, while the interior remain liquid. The liquid lava flows out as it is insulated by the hardened crust above. These caves are found where there are relatively recent basaltic volcanoes in New Zealand, such as the Auckland Volcanic Field particularly on Rangitoto, Mount Eden and Matukutururu.[43]

The distribution of sea caves is more sporadic, with their location and orientation being controlled by weakness in the underlying rock. As cave systems take many thousands of years to develop they can now be isolated from the water that formed them, whether through change in sea level or groundwater flow.[44] If as a cave grows it breaks through to the surface somewhere else it becomes a natural arch, like those near Karamea (Oparara Arches).[45]

Rivers and lakes

The proportion of New Zealand's area (excluding estuaries) covered by rivers, lakes and ponds, based on figures from the New Zealand Land Cover Database, is (357526 + 81936) / (26821559 – 92499–26033 – 19216) = 1.6%.[46] If estuarine open water, mangroves, and herbaceous saline vegetation are included, the figure is 2.2%.[46]

The mountainous areas of the North Island are cut by many rivers, many of which are swift and unnavigable. The east of the South Island is marked by wide, braided rivers such as the Wairau, Waimakariri and Rangitātā; formed from glaciers, they fan out into many strands on gravel plains. The Waikato, flowing through the North Island, is the New Zealand's longest river, with a length of 425 kilometres (264 mi).[47] New Zealand's rivers feature hundreds of waterfalls; the most visited set of waterfalls are the Huka Falls that drain Lake Taupo.[48]

Lake Taupo, located near the centre of the North Island, is the largest lake by surface area in the country. It lies in a caldera created by the Oruanui eruption, the largest eruption in the world in the past 70,000 years. There are 3,820 lakes with a surface area larger than one hectare.[49] Many lakes have been used as reservoirs for hydroelectric projects.[28]

Climate

The main geographic factors that influence New Zealand's climate are the temperate latitude, with prevailing westerly winds; the oceanic environment; and the mountains, especially the Southern Alps. The climate is mostly temperate with mean temperatures ranging from 8 °C (46 °F) in the South Island to 16 °C (61 °F) in the North Island.[50] January and February are the warmest months, July the coldest. New Zealand does not have a large temperature range, apart from central Otago, but the weather can change rapidly and unexpectedly. Near subtropical conditions are experienced in Northland.[51]

Most settled, lowland areas of the country have between 600 and 1,600 mm of rainfall, with the most rain along the west coast of the South Island and the least on the east coast of the South Island and interior basins, predominantly on the Canterbury Plains and the Central Otago Basin (about 350 mm (14 in) PA). Christchurch is the driest city, receiving about 640 mm (25 in) of rain PA, while Hamilton is the wettest, receiving more than twice that amount at 1,325 mm (52.2 in) PA, followed closely by Auckland. The wettest area by far is the rugged Fiordland region, in the south-west of the South Island, which has between 5,000 and 8,000 mm (200 and 310 in) of rain PA, with up to 15,000 mm in isolated valleys, amongst the highest recorded rainfalls in the world.[52]

The UV index can be very high and extreme in the hottest times of the year in the north of the North Island. This is partly due to the country's relatively little air pollution compared to many other countries and the high sunshine hours. New Zealand has very high sunshine hours with most areas receiving over 2000 hours per year. The sunniest areas are Nelson/Marlborough and the Bay of Plenty with 2,400 hours per year.[53]

The table below lists climate normals for the warmest and coldest months in New Zealand's six largest cities. North Island cities are generally warmest in February. South Island cities are warmest in January.

| Location | Jan/Feb (°C) | Jan/Feb (°F) | July (°C) | July (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auckland | 23/16 | 74/60 | 14/7 | 58/45 |

| Wellington | 20/13 | 68/56 | 11/6 | 52/42 |

| Christchurch | 22/12 | 72/53 | 10/0 | 51/33 |

| Hamilton | 24/13 | 75/56 | 14/4 | 57/39 |

| Tauranga | 24/15 | 75/59 | 14/6 | 58/42 |

| Dunedin | 19/11 | 66/53 | 10/3 | 50/37 |

Human geography

Political geography

New Zealand has no land borders.[55] However, the Ross Dependency, its claim in Antarctica, notionally borders the Australian Antarctic Territory to the west and unclaimed territory to the east. Most other countries do not recognise territorial claims in Antarctica.[56]

New Zealand proper is subdivided into sixteen regions: seven in the South Island and nine in the North.[57] They have a geographical link with regional boundaries being based largely on drainage basins.[58] Among the regions, eleven are administered by regional authorities (top tier of local government), while five are unitary authorities that combine the functions of regional authorities and those of territorial authorities (second tier). Regional authorities are primarily responsible for environmental resource management, land management, regional transport, and biosecurity and pest management. Territorial authorities administer local roading and reserves, waste management, building consents, the land use and subdivision aspects of resource management, and other local matters.[58]

The Chatham Islands is not a region, although its council operates as a region under the Resource Management Act. There are a number of outlying islands that are not included within regional boundaries. The Kermadecs and the Subantarctic Islands are inhabited only by a small number of Department of Conservation staff.[59]

Population geography

The South Island contains a little under one-quarter of the population. Over three-quarters of New Zealand's population live in the North Island, with one-third of the total population living in the Auckland Region.[60] Auckland is also the fastest growing region, accounting for 51 percent of New Zealand's total population growth (in the two decades up to 2016).[61] The majority of the indigenous Māori people live in the North Island (87 percent), although a little under a quarter (24 percent) live in Auckland. New Zealand is a predominantly urban country, with 84.1 percent of the population living in an urban area. About 65.4 percent of the population live in the 20 main urban areas (population of 30,000 or more) and 44.2 percent live in the four largest cities of Auckland, Christchurch, Wellington, and Hamilton.[60] New Zealand's population density of around 18 inhabitants per square kilometre[60] is among the lowest in the world.[62]

New Zealand's peoples have been defined by their immigrant origin, the ongoing process of adaptation to a new land, being changed and changing those who came before. This process has led to a distinct distribution of culture across New Zealand. Here language and religion are used as markers for the far richer concept of culture. These metrics unfortunately exclude the political rural-urban divide[63] and also the full effects of the Christchurch earthquakes on New Zealand's cultural distribution.[64][65]

New Zealand's most widely spoken language is English (89.8 percent), however, language, dialect and accent varies spatially both within and between ethnic groups. The Māori language (3.5 percent)[55] is spoken more commonly in areas with large Māori populations (Gisborne, Bay of Plenty and Northland).[66] There are many sub dialects of Māori, the most pronounced division being between the northern and southern tribes.[67] While migration (typically from north to south) was constant throughout the 16–18th centuries, the south maintained a distinct culture largely due to lack of cultivation possible at that latitude. English is spoken with regional accents relating to the origin of immigrants; for example Scottish and English 19th century immigration in Southland and Canterbury respectively.[68][69] This has also occurred with more recent immigration, with a wide variety of accents being common in larger cities where immigrant groups have preferentially settled. These immigrant groups change location with time and accents fade over generations.[70][71]

A wide variety of other languages make up the remaining approximately 6 percent of New Zealanders—with Samoan, Hindi, French and various Chinese dialects being the most common.[55] These minority foreign languages are concentrated in the main cities, particularly Auckland where recent immigration groups have settled.[72]

Agricultural geography

A relatively small proportion of New Zealand's land is arable (1.76 percent), and permanent crops cover 0.27 percent of the land. 7,210 square kilometres (2,780 sq mi) of the land is irrigated.[55] As the world's largest exporter of sheep, New Zealand's agricultural industry focuses primarily on pastoral farming, particularly dairy and beef, as well as lambs. Dairy, specifically, is their top export.[73] In addition to pastoral farming, fisherman harvest mussels, oysters and salmon, and horticulture farmers grow kiwifruit, as well as peaches, nectarines, etc.[74] New Zealand's distance from world markets and spatial variation in rainfall, elevation and soil quality have defined the geography of its agriculture industry.

As of 2007, almost 55 percent of New Zealand's total land area was being used for farming, which is standard compared to most developed countries. Three-fourths of it was pastoral land using for raising sheep, beef, deer, etc. The amount of farmland has decreased since 2002.[75]

New Zealand's isolated location has simultaneously lead to fewer pests and an agriculture industry with a greater susceptibility to introduced diseases and pests.[76] A major concern for New Zealand farmers is the rapidly growing wild rabbit population. Wild rabbits have been an agricultural since their introduction to the country in the 1930s. They cause significant damage to farm lands: eating the grass, crops, and causing soil degradation. Many farmers are worried about their livelihoods and the effects that the rabbits will have on food supply and trade, as their numbers are quickly growing out of control. An illegal rabbit-killing virus called the rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) was released in 1997 by a group of vigilante farmers, and was very effective initially.[77] After twenty years, however, the rabbits became immune to it. A new strain of the virus was released in March 2018, a Korean form of the strain called the K5 virus, or RHDV1-K5. This virus was introduced with the goal of exterminating 40 percent of the rabbit population. The new virus works much faster than the last one, expected to kill rabbits within two to four days of exposure. The virus has become a subject of debate among animal rights activists, due to the inhumane manner in which it kills the rabbits. However, farmers unanimously seem to be very grateful for the release of the virus.[78]

Almost half of New Zealand's climate change emissions are generated by greenhouse gases, mainly methane and nitrous oxide, which come from farming and agriculture. Organisms that grow inside of grazing animals' stomachs turn New Zealand's grass into methane. The increase of carbon dioxide in the air helps the plants to grow faster, but the long-term effects of climate change threaten farmers with the likelihood of more frequent and severe floods and droughts.[79] Growers of kiwifruit, a major export in the horticulture industry of New Zealand, have experienced difficulties as a result of climate change. In the 2010s, warm winters did not provide the adequate cool temperatures needed for the flowering of kiwifruit, and this resulted in a reduction of the yield sizes. Droughts have also decreased apple production by causing sunburns and a lack of water available for irrigation. In contrast, the dairy industry has not been affected, and has actually adjusted well to the effects of climate change.[80]

Natural hazards

Flooding is the most regular natural hazard.[81] New Zealand is swept by weather systems that bring heavy rain; settlements are usually close to hill-country areas which experience much higher rainfall than the lowlands due to the orographic effect. Mountain streams which feed the major rivers rise rapidly and frequently break their banks covering farms with water and silt.[82] Close monitoring, weather forecasting, stopbanks, dams, and reafforestation programmes in hill country have ameliorated the worst effects.[83]

New Zealand experiences around 14,000 earthquakes a year,[84] some in excess of magnitude 7 (M7). Since the 2010, several large (M7, M6.3, M6.4, M6.2) and shallow (all <7 km) earthquakes have occurred immediately beneath Christchurch.[85] These have resulted in 185 deaths, widespread destruction of buildings and significant liquefaction.[86] These earthquakes are releasing distributed stress in the Pacific plate from the ongoing collision with the Indo-Australian plate to the west and north of the city. Volcanic activity is most common on the central North Island Volcanic Plateau. Tsunamis affecting New Zealand are associated with the Pacific Ring of Fire.[87]

Droughts are not regular and occur mainly in Otago and the Canterbury Plains and less frequently over much of the North Island between January and April. Forest fires were rare in New Zealand before the arrival of humans.[88] Fire bans exist in some areas in summer.[89]

Environment and ecology

New Zealand's geographic isolation for 80 million years[90] and island biogeography has influenced evolution of the country's species of animals, fungi and plants. Physical isolation has not caused biological isolation, and this has resulted in a dynamic evolutionary ecology with examples of very distinctive plants and animals as well as populations of widespread species.[91][92] Evergreens such as the giant kauri and southern beech dominate the forests. It also has a diverse range of birds, several of which are flightless such as the kiwi (a national icon), the kakapo, the takahē and the weka,[93] and several species of penguins.[94] Around 30 bird species are currently listed as endangered or critically endangered.[95] Conservationists recognised that threatened bird populations could be saved on offshore islands, where, once predators were exterminated, bird life flourished again.[96]

Many bird species, including the giant moa, became extinct after the arrival of Polynesians, who brought dogs and rats, and Europeans, who introduced additional dog and rat species, as well as cats, pigs, ferrets, and weasels.[97] Native flora and fauna continue to be hard-hit by invasive species. New Zealand conservationists have pioneered several methods to help threatened wildlife recover, including island sanctuaries, pest control, wildlife translocation, fostering, and ecological restoration of islands and other selected areas.[98]

Massive deforestation occurred after humans arrived,[99] with around half the forest cover lost to fire after Polynesian settlement.[100] Much of the remaining forest fell after European settlement, being logged or cleared to make room for pastoral farming, leaving forest occupying only 23 percent of the land.[101] New Zealand had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.12/10, ranking it 55th globally out of 172 countries.[102]

Pollution, particularly water pollution, is one of New Zealand's most significant environmental issues. Fresh water quality is under pressure from agriculture, hydropower, urban development, pest invasions and climate change,[103] although much of the country's household and industrial waste is now increasingly filtered and sometimes recycled.

Protected areas

Some areas of land, the sea, rivers or lakes are protected by law, so their special plants, animals, landforms and other features are safe from harm. New Zealand has three World Heritage Sites,[104] 13 national parks, 34 marine reserves, and thousands of scenic, historic, recreation and other reserves.[105] The Department of Conservation is responsible for managing 8.5 million hectares of public land (approximately 30 percent of New Zealand's total land area).[106]

Environmental agreements

New Zealand is party to several multilateral environmental agreements.[107] The major agreements are listed below.

Popular culture

New Zealand's varied landscape has appeared in television shows, such as Xena: Warrior Princess. An increasing number of feature films have also been filmed there, including the Lord of the Rings trilogy.[108]

New Zealand is often mistakenly omitted from world maps due to the country's geographic isolation and its positioning on the extreme bottom-right in many map projections.[109][110][111]

References

- Walrond, Carl (8 February 2005). "Natural environment – Geography and geology". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Island Countries of the World". WorldAtlas.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Cox, C. Barry; Moore, Peter D.; Ladle, Richard (2016). Biogeography: An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach. John Wiley & Sons. p. 238. ISBN 9781118968581.

- Hobbs, Joseph J. (2008). World Regional Geography. Cengage Learning. p. 9. ISBN 978-0495389507. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- McKenzie, D. W. (1987). Heinemann New Zealand atlas. Heinemann Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7900-0187-6.

- McSaveney, Eileen (24 September 2007). "Nearshore islands". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- Ministry for the Environment. 2005. Offshore Options: Managing Environmental Effects in New Zealand's Exclusive Economic Zone. Introduction Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- McSaveney, Eileen. "Landscapes – overview". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- McLintock, A. H., ed. (1966). "Cook Strait – The Sea Floor". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Cook Strait, New Zealand". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2018.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Walrond, Carl (February 2005). "Natural environment – The bush and its plants". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Richards, Rhys (12 September 2012). "Chatham Islands". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

They are to the east of New Zealand – 862 kilometres from Christchurch but only 772 kilometres from Napier.

- "Hauraki Gulf islands". Auckland City Council. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- Hindmarsh (2006). "Discovering D'Urville". Heritage New Zealand. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- "Distance tables". Auckland Coastguard. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- Bennett, Joe (2005). A Land of Two-Halves. Simon and Schuster. p. 59. ISBN 9780743263573.

- "The Extreme Points of New Zealand". 29 March 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Antipodes Map – Tunnel to the other side of the world". www.antipodesmap.com. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Antipodes Islands". Twelve Mile Circle. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- Goldie, Matthew Boyd (2010). The Idea of the Antipodes: Place, People, and Voices. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 9781135272180.

- Wallis, G. P.; Trewick, S. A. (2009). "New Zealand phylogeography: evolution on a small continent". Molecular Ecology. 18 (17): 3548–3580. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04294.x. PMID 19674312.

- Lewis, Keith; Nodder, Scott; Carter, Lionel (March 2009). "Sea floor geology – Active plate boundaries". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- "The Power of Taupo". www.nzgeo.com. New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Wilson, C. J. N.; Ambraseys, N. N.; Bradley, J.; Walker, G. P. L. (1980). "A new date for the Taupo eruption, New Zealand". Nature. 288 (5788): 252–253. Bibcode:1980Natur.288..252W. doi:10.1038/288252a0. S2CID 4309536.

- Matthew Hall (2004) Existing and Potential Geothermal Resource for Electricity Generation. Ministry for Economic Development.

- "Rotorua Geothermal Sites – Geothermal Sites in Rotorua New Zealand". New Zealand on the Web. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "M 6.5 Cook Strait Sun, Jul 21 2013". GeoNet. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

A magnitude 6.5 earthquake occurred 20 km east of Seddon, New Zealand on Sun Jul 21 2013 5:09 PM

- About 58 percent of New Zealand's electricity was hydroelectric in 2002. Veronika Meduna. 'Wind and solar power Archived 19 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine', Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 September 2007.

- COOPER, A. F. (1 October 1972). "Progressive Metamorphism of Metabasic Rocks from the Haast Schist Group of Southern New Zealand". Journal of Petrology. 13 (3): 457–492. Bibcode:1972JPet...13..457C. doi:10.1093/petrology/13.3.457.

- Harrington, H. J.; Wood, B. L. (1958). "Quaternary andesitic volcanism at the Solander Islands". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 1 (3): 419–431. doi:10.1080/00288306.1958.10422772. ISSN 0028-8306.

- Grant, David (May 2015). "Southland region – Geology and landforms". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Kisch, Conrad (2009). Destination. New Zealand. Gyldendal Uddannelse. p. 11. ISBN 9788702075847.

- McSaveney, Eileen (24 September 2007). "Glaciers and glaciation". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zelaand. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Aoraki/Mt Cook shrinks by 30m". Stuff.co.nz. 16 January 2014.

- Dennis, Andy (2 February 2017). "Mountains – South Island mountains". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- New Zealand Department of Conservation. "Crater Lake". Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- "Eruption of Mt Tarawera". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Dennis, Andy (2 February 2017). "Mountains". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- Dennis, Andy (2 February 2017). "Mountains – Alpine plants and animals". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- Williams, Paul (18 May 2017). New Zealand Landscape: Behind the Scene. Elsevier. ISBN 9780128125656.

- "Things to see and do in Waitomo Caves, New Zealand". www.newzealand.com. Tourism New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Te Anau Glowworm Caves: Explore Te Anau's unique glowworm caves". Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "The lava caves hidden beneath suburban Auckland". New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- Wilson, Kerry-Jayne (2013). West Coast Walking: A Naturalist's Guide. Canterbury University Press. p. 137. ISBN 9781927145425.

- Williams, Paul (2007). "Limestone country - Other karst features". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Historical environmental reporting". Ministry for the Environment of New Zealand. 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Young, David (24 September 2007). "Rivers". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Phillips, Jock (24 September 2007). "Waterfalls". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "List of lakes of New Zealand". TheGrid. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- From NIWA Science climate overview.

- Mullan, Brett; Tait, Andrew; Thompson, Craig (12 September 2006). "Climate". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- "Mean monthly rainfall". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original (XLS) on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- "Mean monthly sunshine hours". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original (XLS) on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Climate data and activities". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. 28 February 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- New Zealand. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2015. pp. 537–542. ISBN 9780160925535.

- "Who owns Antarctica?". Australian Department of the Environment and Energy. 8 September 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "New Zealand – A regional profile". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- OECD Territorial Reviews OECD Territorial Reviews: The Metropolitan Region of Rotterdam-The Hague, Netherlands. OECD Publishing. 2016. p. 169. ISBN 9789264249387.

- "NZ Outlying Islands Regional Information & Travel Information". www.tourism.net.nz. New Zealand Tourism Guide. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Population estimate tables - NZ.Stat". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- "Population Growth in 2016". Greater Auckland. 30 October 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Population density – Country Comparison". www.indexmundi.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Election shows rural-urban divide shrinking, not growing". Stuff. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "10,600 people leave Christchurch". Stuff. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Pickles, Katie (15 March 2016). Christchurch Ruptures. Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 9780908321308.

- "Māori language speakers". The Social Report 2016 – Te pūrongo oranga tangata. socialreport.msd.govt.nz (Report). Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "Warning minority dialects could be lost". Radio New Zealand. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "What is the Southland accent? – The Insider's Guide to UC | Tūpono". The Insider's Guide to UC | Tūpono. 9 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Wall, Arnold (1966). "The Southland Dialect". In McLintock, A. H. (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Tan Lincoln, Tan (8 July 2017). "When does Asian come to mean Kiwi?". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Ng, K. Emma (10 July 2017). Old Asian, New Asian. Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 9780947518516.

- Bell, Allan; Harlow, Ray; Starks, Donna (2005). Languages of New Zealand. Victoria University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-86473-490-7.

- "Working in Dairy Farming | Guide for Migrants | New Zealand Now". www.newzealandnow.govt.nz. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Not just sheep! All about farming in New Zealand". www.newzealand.com. Tourism New Zealand. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Measuring New Zealand's Progress Using a Sustainable Development Approach: 2008". archive.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Goldson, SL; Bourdôt, GW; Brockerhoff, EG; Byrom, AE; Clout, MN; McGlone, MS; Nelson, WA; Popay, AJ; Suckling, DM; Templeton, MD (2015). "New Zealand pest management: current and future challenges". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 45 (1): 31–58. doi:10.1080/03036758.2014.1000343. ISSN 0303-6758. S2CID 84250306.

- "Hopes nationwide release of K5 rabbit virus will kill more than 40% of the population". Stuff. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Why NZ is releasing a rabbit-killing virus". BBC News. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Stowell, Laurel. "Farmers react to climate change". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Kenny, Gavin (September 2001). "Climate Change: Likely Impacts on New Zealand Agriculture" (PDF). Ministry for the Environment.

- McSaveney, Eileen (1 August 2017). "Floods – New Zealand's number one hazard". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Causes of flooding". Environment Canterbury. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- McSaveney, Eileen (1 August 2017). "Floods – New Zealand's number one hazard". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Radio NZ news Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine report on 2007 Gisborne earthquake

- Nicholls, Paul. "Christchurch Quake Map – Earthquakes since September 4 2010". www.christchurchquakemap.co.nz. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Christchurch earthquake kills 185: 22 February 2011". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Volcanoes – Pacific Ring of Fire". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- Dennys Guild; Murray Dudfield (2009). A history of fire in the forest and rural landscape in New Zealand Part 1, pre-Maori and pre-European influences (PDF). New Zealand Institute of Forestry. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Fire management". www.doc.govt.nz. New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Cooper, R.; Millener, P. (1993). "The New Zealand biota: Historical background and new research". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 8 (12): 429–33. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(93)90004-9. PMID 21236222.

- Trewick SA, Morgan-Richards M. 2014. New Zealand Wild Life. Penguin, New Zealand. ISBN 9780143568896

- Lindsey, Terence; Morris, Rod (2000). Collins Field Guide to New Zealand Wildlife. HarperCollins (New Zealand) Limited. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-86950-300-0.

- Wilson, Kerry-Jayne (24 September 2007). "Land birds – overview". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Penguins". www.doc.govt.nz. New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "New Zealand's threatened birds". www.doc.govt.nz. New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Offshore islands". www.doc.govt.nz. New Zealand Department of Conservation. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Holdaway, Richard (24 September 2007). "Extinctions – New Zealand extinctions since human arrival". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Jones, Carl (2002). "Reptiles and Amphibians". In Perrow, Martin; Davy, Anthony (eds.). Handbook of ecological restoration: Principles of Restoration. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-521-79128-1.

- Swarbrick, Nancy (24 September 2007). "Logging native forests'". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- McGlone, M.S. (1989). "The Polynesian settlement of New Zealand in relation to environmental and biotic changes" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 12(S): 115–129. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2014.

- Taylor, R. and Smith, I. (1997). The state of New Zealand’s environment 1997. Ministry for the Environment, Wellington.

- Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723.

- Gluckman, Sir Peter (12 April 2017). "New Zealand's Fresh Waters" (PDF). Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor.

- "New Zealand". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Molloy, Les (September 2015). "Protected areas". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "New Zealand – Country Profile". Convention on Biological Diversity. UN. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Multilateral environmental agreements". www.mfe.govt.nz. Ministry for the Environment. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "This Dreamy Destination Continues to Inspire Fantasy Writers". National Geographic. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "The country that keeps getting left off maps". BBC News. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Morris, Hugh (13 November 2017). "New Zealand keeps getting left off world maps – and Kiwis aren't happy". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Frost, Natasha (2 May 2018). "Why Is New Zealand So Often Left Off World Maps?". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geography of New Zealand. |

- Statistics New Zealand

- New Zealand profile at World Atlas

- Natural Environment – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- New Zealand's Geological History – 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/.