Solo Man

Solo Man (Homo erectus soloensis) is a subspecies of H. erectus which lived along the Solo River in Java, Indonesia, about 117 to 108 thousand years ago in the Late Pleistocene. It is known from 14 skulls, two tibiae, and a piece of the pelvis excavated near the village Ngandong, possibly in addition to three skulls from Sambungmacan and a skull from Ngawi. The Ngandong site was first excavated from 1931 to 1933 under the direction of Willem Frederik Florus Oppenoorth, Carel ter Haar, and Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald, but further study was set back by the Great Depression, World War II, and the Indonesian War of Independence.

| Solo Man | |

|---|---|

| |

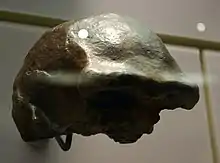

| Cast of Skull X at the Hall of Human Origins, Washington, D.C. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | H. e. soloensis |

| Trinomial name | |

| Homo erectus soloensis Oppenoorth, 1932 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Solo Men skulls are oval-shaped in top view, with heavy brows, inflated cheek bones, and a prominent occipital bun. Brain volume was quite large ranging from 1,013 to 1,251 cc (compared to 1,270 cc for present-day males and 1,130 for present-day females). One female may have been 158 cm (5 ft 2 in) in height and 51 kg (112 lb) in weight, and males were probably much bigger than females.

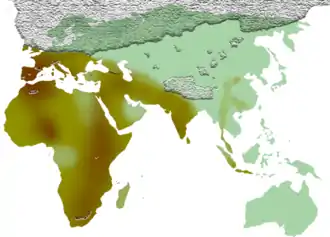

The Solo Men likely inhabited an open woodland environment along with elephants, tigers, gaur, tapirs, hippos, and more. For stone tools, they produced simple flakes and cores. They probably descended from H. e. erectus which had earlier inhabited Java. In accordance with historical race concepts, Indonesian H. erectus were originally classified as the direct ancestors of Aboriginal Australians. The Solo Men are now generally thought to have no living descendants because they far predate modern human immigration into the area roughly 55,000 years ago (though the Solo Men may have encountered the Denisovans, who in turn interbred with modern humans). The Ngandong specimens likely died during a volcanic eruption, and the species as a whole probably went extinct on Java with the takeover of tropical rainforest, beginning by 125,000 years ago. The skulls sustained wounds, but it is unclear if these injuries are the result of an assault, cannibalism, the volcanic eruption, or the fossilisation process.

Taxonomy

Research history

Despite what Charles Darwin had hypothesised in his 1871 Descent of Man, many late-19th century evolutionary naturalists postulated that Asia (instead of Africa) was the birthplace of humankind as it is midway between Europe and America, providing optimal dispersal routes throughout the world (Out of Asia theory). Among the latter was Ernst Haeckel who argued that the first human species (which he proactively named "Homo primigenius") evolved on the now-disproven hypothetical continent "Lemuria" in what is now Southeast Asia, from a genus he termed "Pithecanthropus" ("ape-man"). "Lemuria" had supposedly sunk below the Indian Ocean, so no fossils could be found to prove this. Nevertheless, Haeckel's model inspired Dutch scientist Eugène Dubois to join the Dutch East India Company and search for his "missing link" in Java. He found a skullcap and a femur (Java Man) at the Trinil site along the Solo River, which he named "P." erectus (using Haeckel's hypothetical genus name) in 1893, and unfruitfully attempted to convince the European scientific community that he had found an upright-walking ape-man dating to the late Pliocene or early Pleistocene, who dismissed his findings as some kind of malformed non-human ape.[1]

In order to find more remains of the Java Man, the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin tasked German zoologist Emil Selenka with continuing excavation of the site, which, following his death, was carried out by his wife and fellow zoologist Margarethe in 1907. Among the members was Dutch geologist Willem Frederik Florus Oppenoorth. The yearlong expedition was unfruitful, but sponsorship of the excavation along the Solo River was continued by the Geological Survey of Java. About two decades later, the Survey funded several expeditions in order to update maps of the island, including maps of Tertiary deposits, with Oppenoorth being made the head of the Java Mapping Program in 1930. Among these was a bed dating to the Pleistocene discovered by Dutch geologist Carel ter Haar in 1931, downriver from the Trinil site, near the village of Ngandong.[2]

From 1931 to 1933, a total of 12 skull pieces (including well preserved skullcaps) as well as two right tibiae (of which one was essentially complete) were recovered under the direction of Oppenoorth, ter Haar, and German-Dutch geologist Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald. Midway through excavation, Oppenoorth retired from the Survey and returned to the Netherlands, replaced by Polish geologist Józef Zwierzycki as head of the Java Mapping Program. Due to the Great Depression, the Survey's focus shifted to economically relevant geology, namely petroleum deposits, and excavation of Ngandong ceased completely in 1933 when Zwierzycki took over. In 1934, ter Haar published important summaries of the Ngandong operations, before contracting tuberculosis whereupon he returned to the Netherlands and died two years later. Von Koenigswald, who was hired principally to study Javan mammals, was let go in 1934. After much lobbying by Zwierzycki in the Survey and receiving funding by the Carnegie Institution for Science, von Koenigswald returned to Java to study archaic humans in 1937, but was too preoccupied with the Sangiran site to continue research at Ngandong.[3]

In 1935, the Solo Men remains were transported to Batavia (today, Jakarta, Java, Indonesia) in the care of local university professor Willem Alphonse Mijsberg, with the hope he would take over study of the specimens. Before he had the opportunity, the fossils were moved to Bandung, West Java, in 1942 due to the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies.[3] Von Koenigswald was interned by the Japanese forces for 32 months. Upon his release as well as the commencement of the Indonesian War of Independence, Jewish-German anthropologist Franz Weidenreich (who had fled China before the Japanese invasion in 1941) made arrangements with the Rockefeller Foundation and The Viking Fund for von Koenigswald, his wife Luitgarde, and the Javan human remains (including the Solo Men) to come to New York. Von Koenigswald and Weidenreich studied the material at the American Museum of Natural History,[4] until Weidenreich's death in 1951[3] (leaving behind a monograph on Solo Man).[5] Von Koenigswald, in his 1956 book Meeting Prehistoric Men, included a 14-page account of the Ngandong project with several unpublished results. The Solo Men came to be stored at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. In 1967, von Koenigswald gave the material to Teuku Jacob for his doctoral research. Jacob also oversaw excavation of Ngandong from 1976 to 1978, and was able to recover two more skull specimens and a pelvic fragment. In 1978, von Koenigswald returned the material to Indonesia, and the Solo Men were moved to the Gadjah Mada University, Special Region of Yogyakarta (south-central Java).[3]

Age and taphonomy

The deposition of these fossils in the Solo terrace at the time of discovery was poorly documented, as Oppenoorth, ter Haar, and von Koenigswald were only onsite for 24 days out of the 27 months of operation (as they needed to oversee other Tertiary sites for the Survey), leaving their geological assistants (namely Samsi and Panudju) to oversee the dig, whose records are now lost. Furthermore, the Survey did not publish the site map for over 75 years. The taphonomy and geological age of the Solo Men have consequently been contentious matters. All 14 specimens were reported to have been found in the upper section of Layer II (out of six layers), which is a 46 cm (18 in) thick stratum with gravelly sand, and volcaniclastic hypersthene andesite. All specimens are thought to have been deposited at around the same time as each other. They were probably deposited in a now-dry arm of the Solo River, about 20 m (66 ft) above the modern river. The site is about 40 m (130 ft) above sea level.[3]

Volcaniclastic rock indicates deposition occurred during an volcanic eruption. Due to the sheer volume of fossils, humans and animals may have concentrated in great number in the valley upstream the site either due to the eruption or extreme drought. The ash would have poisoned the vegetation or at least impeded its growth, leading to starvation and death among herbivores and the Solo Men, accumulating a mass of carcasses decomposing over several months. A lack of carnivore damage could mean the carnivores could feed enough without having to resort to crunching through the bone. When the monsoon season came, lahars streaming from the volcano through the river channels swept the carcasses to the Ngandong site, where they were created a debris jam due to the narrowing of the channel there.[3][6]

Based on the site's height above the present-day river, Oppenoorth suggested the Solo Men dated to the Eemian interglacial, which at the time was roughly constrained to 150 to 100 thousand years ago from the Middle/Late Pleistocene transition.[2] Later biochronological studies (using the animal remains to constrain the age) within the next few years by (non-jointly) Oppenoorth, der Taar, and von Koenigswald agreed with a Late Pleistocene date.[7] The Solo Men were first radiometrically dated in 1988 and again 1989, using uranium–thorium dating, to 200 to 30 thousand years ago, a wide error range.[8] In 1996, the Solo Men were dated, using electron spin resonance dating (ESR) and uranium–thorium isotope-ratio mass spectrometry on the teeth, to 53.3 to 27 thousand years ago; this would have meant Solo Man outlasted its continental relative by at minimum 250,000 years, and was contemporaneous with modern humans in Southeast Asia,[7] who immigrated roughly 55 to 50 thousand years ago.[9] In 2008, gamma spectroscopy on three of the skulls showed that they experienced uranium leaching, and the Solo Men were re-dated to roughly 70 to 40 thousand years ago. This would still make it possible that Solo Man was contemporaneous with modern humans.[8] In 2011, argon–argon dating of pumice hornblende yielded a maximum age of 546±12 thousand years ago, and ESR and uranium–thorium dating of a mammal bone just downstream at the Jigar I site a minimum age of 143 to 77 thousand years ago. This extended interval would make it possible that the Solo Men were instead contemporaries with continental H. erectus, long before modern humans dispersed across the continent.[10] In 2020, the first comprehensive chronology of the Ngandong site was published, which found that: the Solo River was diverted through the site by 500,000 years ago; the Solo terrace was deposited over 316 to 31 thousand years ago; the Ngandong terrace 141 to 92 thousand years ago; and the H. erectus bone bed 117 to 108 thousand years ago. This would mean Solo Man was the last known H. erectus population, and did not interact with modern humans.[6]

Classification

The classification of Aboriginal Australians, due to the conspicuous robustness of the Aboriginal Australian skull compared to that of other modern day populations, has historically been a perplexing question to European science since Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (the founder of anthropology) introduced the topic in 1795 in his De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa ("On the Natural History of Mankind"). Following the conception of evolution by Charles Darwin, English anthropologist Thomas Henry Huxley made parallels between the Aboriginal Australian and European Neanderthal skulls, first in 1863. Later racial anthropologists continued to push for some ancestor–descendant relation until the discovery of Indonesian archaic humans.[11]

Preliminarily, Oppenoorth drew parallels between the Solo Man skull and that of the Rhodesian Men from Africa, Neanderthals, and modern day Aboriginal Australians.[2] At the time, humans were generally believed to have originated in Central Asia, championed primarily by American palaeontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn and his apprentice William Diller Matthew. They believed that Asia was the "mother of continents" and the rising of the Himalayas and Tibet and subsequent drying of the region forced human ancestors to become terrestrial and bipedal. They maintained that populations which retreated to the tropics–namely Dubois' Java Man and the "Negroid race"—substantially regressed. They also rejected Raymond Dart's South African Taung child (Australopithecus africanus) as a human ancestor, favouring the hoax Piltdown Man from Britain.[1] Oppenoorth at first believed the Ngandong material represented an Asian type of Neanderthal which was more closely allied with the Rhodesian Man (also considered a Neanderthal type), and decided to give a generic distinction as "Javanthropus soloensis". Dubois considered Solo Man to be more or less identical with the East Javan Wajak Man (now classified as a modern human), so Oppenoorth subsequently began using the name "Homo (Javanthropus) soloensis".[5] Oppenoorth hypothesised that the Java Man evolved in Indonesia and was the predecessor of modern day Aboriginal Australians, with Solo Man being a transitional fossil. He considered Rhodesian Man a member of this same group. As for the Chinese Peking Man (now H. e. pekinensis), he believed it dispersed west and gave rise to the Neanderthals.[2]

Thus, the ancient Java Man, Solo Man, and Rhodesian Man were commonly grouped together in the "Pithecanthropoid-Australoid" lineage. This was an extension of the multiregional origin of modern humans championed by Weidenreich and American racial anthropologist Carleton S. Coon, who believed that all modern races and ethnicities (which were all classified into separate species or subspecies until the mid-20th century) evolved independently from a local population of archaic human (all of which were subsumed as subspecies of H. erectus by the mid-20th century). The matter was revisited in the 1960s as Pleistocene modern humans were being recovered from Australia. By the 1980s, the recent African origin of modern humans theory overturned the Out of Asia theory as African species like A. africanus became widely accepted as human ancestors, and the multiregional model was reconfigured to say that local populations of archaic humans had intebred and contributed at least some ancestry to modern populations in respective regions. In regard to Aboriginal Australians, this has been supported by anatomical comparisons between Solo Man and the first modern humans in Australia, most notably the Willandra Lake humans.[11] However, the date of 117 to 108 thousand years ago for the Solo Men, predating modern human dispersal through Southeast Asia (and eventually into Australia), is at odds with this conclusion.[6] Due to the advanced characteristics of the Solo Men—including a larger brain size, an elevated cranial vault, reduced postorbital constriction, and a less developed brow ridge—the Solo Men have also been referred to as a unique species as "H. soloensis" (continuing as early as the turn of the 21st century), though this is not well supported considering how much they still resemble earlier H. erectus.[12]

The Solo Men are generally considered to have descended from the Sangiran/Trinil populations (H. e. erectus). The three skulls from Sambungmacan and the skull from Ngawi are anatomically quite similar to the Solo Men, and have variously been assigned to H. e. soloensis or to some intermediary morph between H. e. erectus and H. e. soloensis.[12]

Anatomy

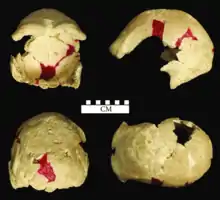

The specimens are:[5]

- Skull I, an almost complete skullcap probably belonging to an elderly female;

- Skull II, a frontal bone probably belonging to a 3 to 7 year old child;

- Skull III, a warped skullcap probably belonging to an elderly individual;

- Skull IV, a skullcap probably belonging to a middle-aged female;

- Skull V, a probable male skullcap—indicated by its great length of 221 mm (8.7 in);

- Skull VI, an almost complete skullcap probably belonging to an adult female;

- Skull VII, a right parietal bone fragment probably belonging to a young, possibly female, individual;

- Skull VII, both parietal bones (separated) possibly belonging to a young male;

- Skull IX, a skullcap missing the base probably belonging to an elderly individual (the small size is consistent with a female, but the heaviness is consistent with a male);

- Skull X, a shattered skullcap probably belonging to a robust elderly female;

- Skull XI, a nearly complete skullcap;

- Tibia A, a few fragments of the shaft, measuring 101 mm (4.0 in) in diamater at the mid-shaft, probably belonging to an adult male;

- Tibia B, a nearly complete right tibia measuring 365 mm (14.4 in) in length at 86 mm (3.4 in) in diameter at the mid-shaft, probably belonging to an adult female;

- Ngandong 15, a partial skullcap;[3]

- Ngandong 16, a left parietal fragment;[3] and

- Ngandong 17, a 4 cm × 6 cm (1.6 in × 2.4 in) left acetabulum (on the pelvis which forms part of the hip joint).[3]

The ages of these specimens were based on the closure of the cranial sutures, assuming they closed at a rate similar to modern humans (though they may have closed at earlier ages in H. erectus). The thickness of the skull ranges from double to triple what would be seen in modern humans. Male and female specimens were distinguished assuming males were more robust than females, though both males and females are exceptionally built compared to other Asian H. erectus. The adult skulls average 202 mm × 152 mm (8.0 in × 6.0 in) in length x breadth, and are proportionally similar to that of the Peking Man, but have a much larger circumference.[5] For comparison, the dimensions of a modern human skull averages 176 mm × 145 mm (6.9 in × 5.7 in) for men and 171 mm × 140 mm (6.7 in × 5.5 in) for women.[13]

The brain volumes of the six Ngandong specimens for which the metric is calculable range from 1,013 to 1,251 cc.[14] For comparison, present-day humans average 1,270 cc for males and 1,130 cc for females.[15] Chinese H. erectus (ranging 780 to 250 thousand years ago) average roughly 1,028 cc, and Javan H. erectus (excluding Ngandong) about 933 cc. Overall, Asian H. erectus are large-brained, roughly 1,000 cc.[16]

Like Peking Man, there was a slight sagittal keel running across the midline of the skull. Compared to other Asian H. erectus, the forehead is proportionally low and also has a low angle of inclination. The brow ridge does not form a continuous bar like in Peking Man, but rather curves downwards at the midpoint, forming a nasal bridge. Like Peking Man, the frontal sinuses are confined to between the eyes rather than extending into the brow region. It is nonetheless quite thick, especially at the lateral ends (nearest the edge of the face). Compared to Neanderthals and modern humans, the area the temporal muscle would have covered is rather flat, but the squamous part of the temporal bone is triangular like that of Peking Man, and the infratemporal crest is quite sharp. The brow ridges merge into markedly thickened cheek bones. The skull is phenozygous, in that the skullcap is proportionally narrow compared to the cheekbones, so that the latter are still visible when looking down at the skull in top-view.[5]

The back of the skull is characterised by an undulating (almost wavy) contour in side-view. There is a sharp, thick occipital torus which marks a clear separation between the occipital and nuchal planes. The occipital torus projects the most at part corresponding to the external occipital protuberance in modern humans. The base of the temporal bone is consistent with Java Man and Peking Man rather than Neanderthals and modern humans. Unlike Neanderthals and modern humans, there is a defined bony pyramid structure near the root of the pterygoid bone. The mastoid part of the temporal bone at the base of the skull notably juts out. The occipital condyles (which connect the skull to the spine) are proportionally small compared to the foramen magnum (where the spinal cord passes into the skull). Large, irregular bony projections lie directly behind the occipital condyles.[5]

Tibia A is much more robust than tibia B, and is overall consistent with Neanderthal tibiae.[5] Like other H. erectus, the tibiae are thick and heavy. Based on the reconstructed length of 380 mm (15 in), tibia B may have belonged to a 158 cm (5 ft 2 in) tall, 51 kg (112 lb) individual. Tibia A is assumed to have belonged to a larger individual. Asian H. erectus, for which height estimates are taken (a rather small sample size), typically range from 150–160 cm (4 ft 11 in–5 ft 3 in), with Indonesian H. erectus in tropical environments typically scoring on the higher end, and continental specimens in colder latitudes on the lower end. The single pelvic fragment from Ngandong has not been formally described yet.[14]

Culture

Palaeohabitat

At species level, the Ngandong Fauna is overall similar to the older Kedung Brubus Fauna roughly 800 to 700 thousand years ago, a time of mass immigration of large mammal species to Java, including Asian elephants and Stegodon. Other Ngandong fauna include the tiger, Malayan tapir, the hippo Hexaprotodon, Rusa deer, water buffalo, gaur, pigs, and crab-eating macaque. These are consistent with an open woodland environment. The driest conditions probably corresponded to the glacial maximum roughly 135,000 years ago, exposing the Sunda shelf and connecting the major Indonesian islands to the continent. By 125,000 years ago, the climate became much wetter, making Java an island, and allowing for the expansion of tropical rainforests. This caused the succession of the Ngandong Fauna by the Punung Fauna, though more typical Punung Fauna—namely modern humans, orangutans, and gibbons—probably could not penetrate the island until it was reconnected to the continent by 80,000 years ago.[17]

H. e. soloensis was the last population of a long occupation history of the island of Java, beginning 1.51 to 0.93 million years ago at the Sangiran site, continuing 540 to 430 at the Trinil site, and finally 117 to 108 thousand years ago at Ngandong. If the date is correct for the Solo Men, then they would represent a terminal population of H. erectus which sheltered in the last open-habitat refuges of East Asia before the rainforest takeover. Before the immigration of modern humans, Late Pleistocene Southeast Asia was also home to H. floresiensis endemic to the island of Flores, Indonesia, and H. luzonensis endemic to the island of Luzon, the Philippines. Genetic analysis of present-day Southeast Asian populations indicates the widespread dispersal of the Denisovans (a species currently only recognisable by their genetic signature) across Southeast Asia, whereupon they interbred with immigrating modern humans 45.7 and 29.8 thousand years ago. About 1% of the Denisovan genome derives from an even more archaic species, pre-dating the Denisovan/Neanderthal/modern human split, possibly a late-surviving H. erectus population.[6]

Judging by the sheer number of specimens deposited at Ngandong, all at the same time, there may have been a sizeable population of H. e soloensis before the volcanic eruption, but this is difficult to approximate with certainty. The Ngandong site was some distance away from the northern coast of the island, but it is unclear where the southern shoreline and the mouth of the Solo River would have been.[3]

Technology

In 1938, von Koenigswald returned to the Ngandong site along with archaeologists Helmut de Terra, Hallam L. Movius, and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin to collect lithic cores and flakes (i.e., stone tools). Because of wearing done by the river, it is difficult to confidently identify some of these rocks as actual tools. They are small and simple, usually smaller than 5 cm (2 in) and made most commonly of chalcedony (but also chert and jasper) washed up by the river. A few volcanic rocks and wood fragments seem to have been modified into heavy duty chopping tools. Like many other Southeast Asian sites predating modern humans, the Ngandong site lacks sophisticated choppers, hand axes, or any other kind of complex chopping tool characteristic of the Acheulean industry of Western Eurasian and African sites. In 1944, Movius suggested this was due to a great technological divide between western and eastern H. erectus caused by a major difference in habitat (open area vs. tropical rainforest), as the chopping tools are generally interpreted as evidence of big game hunting, which he believed was only possible when humans spread out onto open plains.[18]

Though a strict "Movius Line" is not well supported anymore with the discovery of some hand axe technology in Middle Pleistocene East Asia, handaxes are still conspicuously rare and crude in East Asia compared to western contemporaries. This has been variously explain as: the Acheulean was invented in Africa after human dispersal through East Asia (but this would require that the two populations remained separated for nearly 2 million years); East Asia had poorer quality raw materials, namely quartz and quartzite (but some Chinese localities produced handaxes from these materials, and East Asia is not completely void of higher quality minerals); East Asian H. erectus used biodegradable bamboo instead of stone for chopping tools (but this is difficult to test); or East Asia had a lower population density, leaving few tools behind in general (though demography is difficult to approximate in the fossil record).[19]

Cannibalism

In 1951, Weidenreich and von Koenigswald made note of major injuries in Skulls IV and VI, which they believed were caused by, respectively, a cutting instrument and a blunt instrument. They bear of evidence of inflammation and healing, so they probably survived the altercation. Weidenreich and von Koenigswald also noted that only the skullcaps were found, lacking even the teeth, which is highly unusual. So, they interpreted at the least Skulls IV and VI as victims of an "unsuccessful assault", and the other skulls where the base was broken out "the result of more successful attempts to slay the victims." They were unsure if this was done by a neighboring H. e. soloensis tribe, or "by more advanced human beings who would have given evidence of their 'superior' culture by slaying their more primitive fellowsman." The latter scenario had already been proposed for the Peking Man (which has similarly conspicuous pathology) by French palaeontologist Marcellin Boule. Weidenreich and von Koenigswald, nonetheless, conceded that some of the injuries could have been related to the volcanic eruption instead. Von Koenigswald suggested that only skullcaps exist because the Solo Men were modifying skulls into skull cups, but Weidenreich was skeptical of this as the jagged rims of especially Skulls I, V, and X are not well suited for this purpose.[5]

Cannibalism and ritual headhunting have also been proposed for the Trinil, Sangiran, and Modjokerto sites (all in Java) based on the conspicuous lack of any remains other than the skullcap. This has been reinforced by the historic practice of headhunting and cannibalism in some modern Indonesian, Australian, and Polynesian groups. In 1972, Jacob alternatively suggested that because the base of the skull is weaker than the skullcap, and since the remains had been transported through river with large stone and boulders, this was a purely natural phenomenon. As for the lack of the rest of the skeleton, if tiger predation was a factor, tigers usually only leave the head since it has the least amount of meat on it. Further, the Ngandong material, especially Skulls I and IX, were damaged during excavation, cleaning, and preparation.[20]

Notes

- Hsiao-Pei, Y. (2014). "Evolutionary Asiacentrism, Peking Man, and the Origins of Sinocentric Ethno-Nationalism". Journal of the History of Biology. 47: 585–625. doi:10.1007/s10739-014-9381-4.

- Oppenoorth, W. F. F. (1932). "Solo Man—A New Fossil Skull". Scientific American. 147 (3): 154–155. JSTOR 24966028.

- Huffman, O. F.; de Vos, J.; Berkhout, A. W.; Aziz, F. (2010). "Provenience reassessment of the 1931-1933 Ngandong Homo erectus (Java), confirmation of the bone-bed origin reported by the discoverers". Paleoanthropology. doi:10.4207/PA.2010.ART34.

- Tobias, P. V. (1976). "The life and times of Ralph von Koenigswald: Palaeontologist extraordinary". Journal of Human Evolution. 5 (5): 406–410. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(76)90082-8.

- Weidenreich, F.; von Koenigswald, G. H. R. (1951). "Morphology of Solo man". Anthropological papers of the AMNH. 43: 228–249.

- Rizal, Y.; Westaway, K. E.; Zaim, Y.; van den Bergh; et al. (2020). "Last appearance of Homo erectus at Ngandong, Java, 117,000–108,000 years ago". Nature. 577 (7790): 381–385. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1863-2. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 31853068.

- Swisher, III, C. C.; Rink, W. J.; Antón, S. C.; et al. (1996). "Latest Homo erectus of Java: Potential Contemporaneity with Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia". Science. 274 (5294): 1870–1874. JSTOR 2891688.

- Yokoyama, Y.; Falguères, C.; Sémah, F.; Jacob, T. (2008). "Gamma-ray spectrometric dating of late Homo erectus skulls from Ngandong and Sambungmacan, Central Java, Indonesia". Journal of Human Evolution. 55 (2): 274–277. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.01.006.

- O'Connell, J. F.; Allen, J.; Williams, M. A. J.; et al. (2018). "When did Homo sapiens first reach Southeast Asia and Sahul?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (34): 8482–8490. doi:10.1073/pnas.1808385115.

- Indriati, E.; Swisher III, C. C.; Lepre, C.; et al. (2011). "The Age of the 20 Meter Solo River Terrace, Java, Indonesia and the Survival of Homo erectus in Asia". PLoS One. 6 (6): e21562. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021562. PMC 3126814. PMID 21738710.

- Curnoe, D. (2011). "A 150-Year Conundrum: Cranial Robusticity and Its Bearing on the Origin of Aboriginal Australians". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. doi:10.4061/2011/632484.

- Kaifu, Y.; Aziz, F.; et al. (2008). "Cranial morphology of Javanese Homo erectus: New evidence for continuous evolution, specialization, and terminal extinction". Journal of Human Evolution. 55 (4): 551–580. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.05.002.

- Li, H.; Ruan, J.; Xie, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, W. (2007). "Title: Investigation of the critical geometric characteristics of living human skulls utilising medical image analysis techniques". International Journal of Vehicle Safety. 2 (4): 345–367. doi:10.1504/IJVS.2007.016747.

- Antón, S. C. (2003). "Natural history of Homo erectus†". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 122 (37): 136–152. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10399.

- Allen, J. S.; Damasio, H.; Grabowski, T. J. (2002). "Normal neuroanatomical variation in the human brain: an MRI-volumetric study". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 118 (4): 341–358. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10092. PMID 12124914. S2CID 21705705.

- Antón, S. C.; Taboada, H. G.; et al. (2016). "Morphological variation in Homo erectus and the origins of developmental plasticity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 371 (1698): 20150236. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0236. PMC 4920293. PMID 27298467.

- Van den Bergh, G. D.; de Vos, J.; Sondaar, P. Y. (2001). "The Late Quaternary palaeogeography of mammal evolution in the Indonesian Archipelago". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 171 (3–4): 387–392. doi:10.1016/s0031-0182(01)00255-3.

- Bartstra, G.-J.; Soegondho, S.; van der Wijk, A. (1988). "Ngandong man: age and artifacts". Journal of Human Evolution. 17 (3): 325–337. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(88)90074-7.

- Lycett, S. J.; Bae, C. J. (2010). "The Movius Line controversy: the state of the debate". World Archaeology. 42 (4): 526–531. JSTOR 20799447.

- Jacob, T. (1972). "The Problem of Head-Hunting and Brain-Eating among Pleistocene Men in Indonesia". Archaeology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania. 7 (2): 81–91. JSTOR 40386169.

External links

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).