Yuanmou Man

Yuanmou Man (simplified Chinese: 元谋人; traditional Chinese: 元謀人; pinyin: Yuánmóu Rén), Homo erectus yuanmouensis, refers to a member of the genus Homo whose remnants, two incisors, were discovered near Danawu Village in Yuanmou County in southwestern province of Yunnan, China. Later, stone artifacts, pieces of animal bone showing signs of human work and ash from campfires were also dug up from the site. The fossils are on display at the National Museum of China, Beijing.

| Yuanmou Man | |

|---|---|

_-_cropped.png.webp) | |

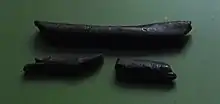

| Casts of the teeth of Yuanmou Man | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †H. e. yuanmouensis |

| Trinomial name | |

| Homo erectus yuanmouensis Hu et al., 1973 | |

Taxonomy

Discovery

On May 1, 1965, geologist Qian Fang recovered two archaic human upper first incisors (V1519) from fossiliferous deposits of the Yuanmou Basin near Shangnabang village, Yuanmou County, Yunnan Province, China.[1][2] When they were formally described in 1973, they were determined to have belonged to a young male.[1] Qian's field team was funded by the Chinese Academy of Geosciences. The Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology funded further excavation of the site, and reported 16 stone tools, of which six were found in situ and 10 nearby.[2]

The Yuanmou Basin sits just to the southeast of the Tibetan Plateau, and is the lowest basin on the central Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau at an elevation of 1,050–1,150 m (3,440–3,770 ft). The Yuanmou Formation is divided into four members and 28 layers. The human teeth were discovered in the silty clay and sandy conglomerates of Member 4 (the uppermost member) near the bottom of layer 25.[2][3]

In December 1984, a field team dispatched by the Beijing Natural History Museum to survey the Guojiabao site, just 250 m (820 ft) away from the original Yuanmou Man teeth, unearthed a left human tibial shaft in a layer just overlying Member 4. The tibia was described in 1991, and was determined to belong to a young female H. e. yuanmouensis.[4][2]

Age

The Yuanmou Formation has been identified as a fossil-bearing site since the 1920s, and palaeontological work on the area suggest a Lower Pleistocene age. Because the formation is faulted (several rock masses have been displaced), biostratigraphy (dating an area based on animal remains) of the human-bearing layer is impossible.[3]

In 1976, Li Pu and colleagues palaeomagnetically dated the incisors to the Gilsa geomagnetic polarity event roughly 1.7 million years ago. In 1977, with a much larger sample size, Cheng Guoliang and colleagues instead placed the area during the Olduvai subchron, and dated it to 1.64–1.63 million years ago. In 1979, Li Renwei and Lin Daxing measured the alloisoleucine/isoleucine protein ratio in animal bones and produced a date of 0.8 million years ago for the Yuanmou Man. In 1983, Liu Dongsheng and Ding Menglin — using palaeomagnetism, biostratigraphy, and lithostratigraphy — reported a date of 0.6–0.5 million years ago during the Middle Pleistocene, despite the animal remains pointing to an older date.[3] In 1988, Q. Z. Liang agreed with Cheng on dating it to the Olduvai subchron. In 1991, Qian and Guo Xing Zhou came to the same conclusion as Liang. In 1998, R. Grün and colleagues, using electron spin resonance dating on 14 horse and rhino teeth, calculated an interval of 1.6–1.1 million years ago.[5] In 2002, Masayuki Hyodo and colleagues, using palaeomagnetism, reported a date of 0.7 million years ago near the Matuyama–Brunhes geomagnetic boundary during the Middle Pleistocene.[6] Later that year, the boundary was re-dated to 0.79–0.78 million years ago. In 2003, Ri Xiang Zhu and colleagues made note of the inconsistency among previous palaeomagnetic studies,[7] and in 2008 palaeomagnetically dated it to roughly 1.7 million years ago. They believed Middle Pleistocene dates were probably caused by too small a sample size. The tibia was probably found somewhere in layers 25–28, and by Zhu's calculations would date to 1.7–1.4 million years ago.[8]

The date of 1.7 million years ago is widely cited.[2] This makes the Yuanmou Man the earliest fossil evidence of humans in China, and is roughly contemporaneous with the oldest humans in Southeast Asia. It was part of a major expansion of H. erectus across Asia, the species extending from 40°N in Xiaochangliang to 7°S in Java, and inhabiting temperate grassland to tropical woodland. The Yuanmou Man is only slightly younger than the Dmanisi hominins from the Caucasus, 1.77–1.75 million years old, who are the oldest evidence of human emigration out of Africa. These dates could therefore mean that humans spread rather rapidly across the Old World, over a period of less than 70,000 years. Yuanmou Man could also indicate humans dispersed from south to north across China, but there are too few other well-constrained early Chinese sites to test this hypothesis.[8]

Classification

The teeth were formally described in 1973 by Chinese palaeoanthropologist Hu Chengzhi, who identified it as a new species of Homo erectus, distinct from and much more archaic than the Middle Pleistocene Peking Man, H. ("Sinanthropus") e. pekinensis, from Beijing. He named it H. ("S.") e. yuanmouensis, and believed it represents an early stage in the evolution of Chinese H. erectus.[1][2] In 1985, Chinese palaeoanthropologist Wu Rukang said that few authors in the field recognise H. e. yuanmouensis as valid, with most favouring there having been only one subspecies of H. erectus which inhabited China.[3]

Anatomy

For the teeth, only the left and right first incisors are preserved for the Yuanmou Man. The left incisor measures 11.4 mm (0.45 in) in breadth and 8.1 mm (0.32 in) in width, and the right incisor 11.5 mm (0.45 in) and 8.6 mm (0.34 in).[8] The incisors are overall robust. They notably flare out in breadth from bottom to top. The labial (lip) side is mostly flat with the exception of some grooves and depressions, and the base is somewhat convex like that of the Peking Man. The lingual (tongue) side caves in like that of the Peking Man, but has a defined ridge running down the middle like H. (e?) ergaster and H. habilis. The cross section at the neck of the tooth (at the gum line) is nearly elliptical.[2][8]

The tibia is gracile and laterally (on the sides) flattened. The anterior (front) aspect is round and obtuse, and has a weak S-curve. The interosseous crest (which separates the muscles on the back of the leg from those of the front of the leg) is shallow. On the posterior (back) aspect, there is a ridge running down the middle, developed attachment for the flexor digitorum longus muscle (which flexes the toes), and a defined soleal line. Like other H. erectus, the tibia is quite thick, constricting the medullary cavity where the bone marrow is stored.[2]

Technology

.png.webp)

In 1973, three retouched tools were found within 20 m (66 ft) of the incisors, two of them in a layer 50 cm (20 in) in elevation below the incisors, and an additional one about 1 m (3 ft 3 in) above the incisors. Three similar tools were recovered at the surface of the Shangnabang site. Within 15 km (9.3 mi), cores, flakes, choppers, pointed tools, and scrapers were found,[3] totaling 16 tools. They were made of quartz and quartzite probably gathered from the nearby river, and most were modified with direct hammering (using a hammerstone to flake off pieces), but a few were modifed with the bipolar technique (smashing the core with the hammerstone, creating several flakes).[2]

References

- Chengzhi, H. (1973). "Ape-man teeth from Yuanmou, Yunnan". Acta Geoscientia Sinica. 1: 71–75.

- Xueping, J. (2014). "Yuanmou". In Smith, C. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_710. ISBN 978-1-4419-0465-2.

- Olsen, J. W.; Miller-Antonio, S. (1992). "The Palaeolithic in Southern China". Asian Perspectives}. 31 (1): 135–138. JSTOR 42929173.

- Zhou, G.; Wang, B.; Zhai, H. (1991). "New material of Yuanmou Man". Kaogu Yu Wenwu. 1: 56–61.

- Grün, R.; Huang, P. H.; et al. (1998). "ESR and U-series analyses of teeth from the palaeoanthropological site of Hexian, Anhui Province, China". Journal of Human Evolution. 34 (6): 555–564. doi:10.1006/jhev.1997.0211.

- Hyodo, M.; Nakaya, H.; Urabe, A.; Saegusa, H.; Xue, S. H.; Yin, J.; Ji, X. (2002). "Paleomagnetic dates of hominid remain from Yuanmou, China, and other Asian sites". Journal of Human Evolution. 43 (1): 27–41. doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0555.

- Zhu, R. X.; et al. (2003). "Magnetostratigraphic dating of early humans in China". Earth-Science Reviews. 61 (3–4): 341–359. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00132-0.

- Zhu, R. X.; et al. (2008). "Early evidence of the genus Homo in East Asia". Journal of Human Evolution. 55 (6): 1075–1085. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.08.005.