Bartow, Florida

Bartow (/ˈbɑːrtoʊ/ BAR-toh) is the county seat of Polk County, Florida, United States. Founded in 1851 as Fort Blount, the city was renamed in honor of Francis S. Bartow, the first brigade commander of the Confederate Army to die in combat during the American Civil War. According to the 2010 Census, the city had a population of 17,298 and an estimated population of 20,147 in 2019.[9] It is part of the Lakeland−Winter Haven Metropolitan Statistical Area, which had an estimated population of 584,383 in 2009. As of 2020, the mayor of Bartow is Scott Sjoblom.

Bartow, Florida | |

|---|---|

| |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): City of Oaks and Azaleas | |

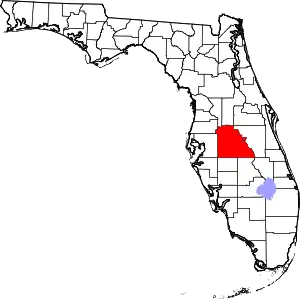

Location of Bartow in Polk County, Florida. | |

Bartow Location in Florida  Bartow Bartow (the United States)  Bartow Bartow (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 27°53′33″N 81°50′23″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Polk |

| First Settled | Pre-Columbian Era |

| Nearby Black Seminole settlement | Late 1810s |

| Resettled | 1851 |

| Incorporated | July 1, 1882 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Scott Sjoblom [1] |

| • City Commission | Members

|

| • City Manager | George A. Long[2] |

| • U.S. Congress | Scott Franklin (R)[3] |

| Area | |

| • City | 52.63 sq mi (136.31 km2) |

| • Land | 46.22 sq mi (119.70 km2) |

| • Water | 6.41 sq mi (16.61 km2) |

| Elevation | 121 ft (37 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • City | 17,298 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 20,147 |

| • Density | 435.92/sq mi (168.31/km2) |

| • Metro | 584,383 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 33830-33831 |

| Area code(s) | 863 |

| Slogan(s) | Our History Comes to Life[6] |

| FIPS code | 12-03675[7] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0278138[8] |

| Website | www |

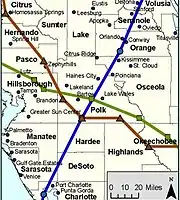

Located near the source of the Peace River, Bartow is approximately 39 miles (63 km) east of Tampa, Florida and 50 miles (80 km) southwest of the Greater Orlando area. The city is near the center of "Lightning Alley" and has frequent afternoon thunderstorms in the summer, but typically has sunny and mild winters. Government, mining, and agriculture are the major sectors of the area's economy. The primary roads in the Bartow area are U.S. Route 17, U.S. Route 98 and State Road 60, which provide access to locations throughout Central Florida.

The official city nickname is the "City of Oaks and Azaleas". Three districts within the city are on the National Register of Historical Places. Other historic landmarks include the Old Polk County Courthouse built in 1909 and Bartow High School, formerly Summerlin Institute, the oldest high school in the county. Summerlin Academy now uses the space and was named for the historic school. Although Bartow has been eclipsed in population, importance and name recognition by other cities in the county, particularly Lakeland and Winter Haven, the city has retained its small city heritage and its distinctive Southern culture. With the annexation of 18,000 acres (73 km2) of former phosphate mining land owned by the Clear Springs Land Company, Bartow's population is projected to increase to over 25,000 by 2025 and over 45,000 by 2030.

History

A Spanish map of the Florida peninsula drawn in 1527 shows a native settlement called Rio de la Paz near present-day Bartow.[10] Little is known about these Native Americans who made their home near present-day Bartow. It is likely that their population suffered high mortality from European diseases, such as smallpox and measles.[10][11] The remnants of these pre-Columbian peoples probably joined the Creek Indians who migrated from the north to become the Seminole Indian tribe.[10]

The first non-Indian settlement in the area was a colony of Black Seminole, free blacks and escaped slaves who established Minatti south of Lake Hancock in the late 1810s.[12] These "maroons", as they were commonly called, were slaves who escaped from Georgia and the Carolinas.[13] The Black Seminole of Minatti were allies of the Red Stick Creek in Talakchopko, a village that preceded present-day Fort Meade.[14] The Seminole leader Osceola had strong ties to Talakchopko. Many of the events leading up to the Second Seminole War were associated with Osceola and the Minatti war chief Harry.[14] By the end of the Second Seminole War in 1842, both Minatti and Talakchopko had been destroyed by US forces.[15]

The Armed Occupation Act of 1842 facilitated European-American settlement of the Florida peninsula in the 1840s, although the act prohibited settlement near the Peace River, as this was considered Seminole land.[10][16] Enforcement of that part of the act was not strictly enforced; however, and settlers eventually moved into the area.[10] As the settlement grew, the residents began to plant citrus trees and build one-room school houses and churches.[10] In 1851, Fort Blount was established by Redding Blount. Bartow developed east of this site.[17] At some point in the 1850s, Fort Blount was renamed as Peace Creek or Peas Creek, which was a translation of the Spanish Rio de la Paz of early maps.[17]

About a month after the secession of Florida in 1861, the state established Polk County from the eastern portion of Hillsborough County.[18] A few months later, the American Civil War began with the Battle of Fort Sumter. Because of the turmoil of secession and the war, the county had no official county seat for its first six years.[19] The state legislature had directed the voters of Polk County to choose a site for the county seat and mandated that the site be named "Reidsville."[19] During the war, the area's major contribution to the Confederacy was supplying food, particularly cattle and beef.[20] The Union army and navy had effective control of the west coast of Florida, and many cattlemen retreated inland and formed the "Cow Cavalry" as a defense against Union troops.[21][20] One of the wealthiest members of the Cow Cavalry was Jacob Summerlin.[20] After Summerlin purchased the Blount property in 1862, he donated a large parcel of land to build a county courthouse, two churches and a school.[19] Later that year, the town which had been known as Fort Blount, Peace Creek, Peas Creek, and briefly Reidsville, was permanently renamed Bartow in honor of Francis S. Bartow, the first Confederate brigade commander to die during the war.[19]

Bartow recovered slowly from the war.[22] The first Polk County Courthouse was built in 1867, which firmly established the city as county seat.[19] Although Florida formally rejoined the union in 1868, the Reconstruction era did not end in Florida until 1877.[23]

The 1880s and 90s were a period of growth for the city of Bartow; from 1880 to 1900, the city would grow from 386 residents to 1,983.[24][25] On July 1, 1882 the town was incorporated as a city.[26] In 1885, the Florida Southern Railroad, a north-south route from North Florida to Southwest Florida opened in Bartow.[27] A year later, the Bartow Branch of the South Florida Railroad, connecting Tampa and Orlando, was completed.[28] The railroads were catalysts for growth of the area; during the Spanish–American War, the Bartow rail yards became a crucial part of the supply line directed at US troops in Cuba.[22] In 1887, Summerlin Institute, the first brick schoolhouse south of Jacksonville, was built.[29]

By the turn of the century, Bartow had become the most populous city south of Tampa on the Florida peninsula – larger than Miami or West Palm Beach.[30]

As the city grew, a number of industries moved into the Bartow area. In the first few decades of the 1900s, thousands of acres of land around the city were purchased by the phosphate industry. Bartow would become the hub of the largest phosphate industry in the United States.[31]

Polk County was the leading citrus county in the United States for much of the 20th century and the city has several large groves. In 1941, the city built an airport northeast of town.[32] The airport was taken over by the federal government during World War II and was the training location for many Army Air Corps pilots during the war.[32] The airport was returned to the city in 1967 and renamed as Bartow Municipal Airport.[32]

For most of the 20th century, Bartow's growth was modest, especially in comparison to the rest of the county and state. While other cities in Polk County aggressively annexed adjacent land and allowed rapid growth, the government of Bartow generally took a more cautious approach.[33][34] Bartow's growth was also limited because most of the land surrounding the city was owned by phosphate mining companies, making residential growth impractical.[33][34] Although Bartow had been the largest city in Polk county in 1900, by the 1910 U.S. Census, Lakeland had surpassed it in population.[35] Bartow remained the second largest city in the county until sometime in the 1950s, when Winter Haven superseded it.[35]

In the late 1990s phosphate operations in the area moved southward, and much of the former phosphate land became available for sale.[33][36] In 1999, Connecticut financier Stanford Phelps purchased the former Clear Springs phosphate lands east and south of city limits; he announced plans for an 18,000-acre development, the largest project in Polk County history.[33][37] After nearly a decade of delays, the plan received final approval in 2009.[37] The Clear Springs Development includes plans for more than 11,000 new homes, 1,000,000 square feet (93,000 m2) of commercial space, three schools, and a golf course.[33] According to the Central Florida Regional Planning Council, Bartow's population is projected to grow to over 25,000 people by 2015.[38][39] When buildout of the Clear Springs Development is completed by 2030, the population of the city is projected to be over 45,000 residents.[38][39]

Geography and climate

Geography

Bartow is located slightly southwest of the geographical centers of both Polk County and peninsular Florida.[40] The city is approximately 39 miles (63 km) east of Tampa and 51 miles (82 km) southwest of Orlando.[41][42] The cities of Bartow, Lakeland, and Winter Haven form a roughly equilateral triangle pointed southward, with Bartow being the south point, Lakeland the west point, and Winter Haven the east point.[43][44] The city is located near the headwaters of the Peace River at Lake Hancock.[45] Bartow is located within the Central Florida Highlands area of the Atlantic coastal plain with a terrain consisting of flatland interspersed with gently rolling hills.[46]

According to the United States Census Bureau, in 2000 the city had a total area of 11.4 square miles (30 km2), of which 11.2 square miles (29 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) (1.23%) is water. As a result of the annexation of over 26,000 acres (110 km2) of undeveloped land, primarily the Clear Springs land, the area of the city has quadrupled to over 52 square miles (130 km2) with more annexation still pending.

Physiography and soils

Bartow is located on the South Central Florida Ridge, as classified by the USDA.[47] Most soils in the Bartow area are sandy; other soils have sandy surface layers and clay subsoils, and the eastern outskirts of town have a clay-rich floodplain through which the Peace River flows. Drainage outside of the floodplain ranges from good to excessive for the most part except for a poorly drained band which cuts across the northern part of town. Much of Bartow is built on the Fort Meade soil series, which is well drained, high in organic matter, and rich in phosphorus, an uncommon combination in Florida, much appreciated by area gardeners.[48][49]

Climate

Bartow, like most of Florida, is located in the humid subtropical zone, as designated by the (Köppen climate classification: Cfa).[50] The climate of Bartow and other inland cities is slightly different than those cities on the coasts of Florida. Typically, the ocean or gulf tends to moderate the climate of cities on the coast. As Bartow is further from the coast than almost any other city in Florida, it tends to have higher daytime temperatures during the summer and cooler temperatures at night during the winter. Regardless, the climate pattern prevalent throughout central Florida is evident in Bartow: hot, humid summers with frequent afternoon thunderstorms and relatively drier and mild winters.[51] On average, a tropical system brings hurricane-force winds to the Polk County area less than once every ten years, although the 2004 hurricane season in which three hurricanes hit within 44 days was a case study in the law of averages.[52] Until 2004, the most recent storm to bring hurricane-force winds to the Bartow area had been Hurricane Donna in 1960.[53] While Florida's vulnerability to hurricanes is well known, hurricanes are not the most common severe weather threat seen in the Polk County area. The area is in the center of "lightning alley", the most concentrated lightning strike area in the United States.[54] Lightning is not the only threat from central Florida thunderstorms. The more severe storms bring the threat of tornadoes, although Florida tornadoes very rarely reach the size of those elsewhere in the United States. Even hail is not out of the question; one storm in March 1996 caused a one-foot accumulation of hail in areas of Bartow.[55]

Freezes are an occasional occurrence in the Bartow area and can be a problem if temperatures remain below freezing for a sustained period of time. On average, the area can expect freezing temperatures every other winter. Snow is a rare phenomenon in the area, perhaps a few times every century.[56]

| Climate data for Bartow, Florida | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

99 (37) |

98 (37) |

96 (36) |

93 (34) |

90 (32) |

103 (39) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

75 (24) |

80 (27) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

85 (29) |

80 (27) |

75 (24) |

83.5 (28.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 51 (11) |

53 (12) |

57 (14) |

61 (16) |

67 (19) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

74 (23) |

73 (23) |

66 (19) |

60 (16) |

53 (12) |

63.3 (17.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

36 (2) |

47 (8) |

56 (13) |

60 (16) |

61 (16) |

55 (13) |

41 (5) |

25 (−4) |

18 (−8) |

18 (−8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.51 (64) |

2.82 (72) |

3.11 (79) |

2.53 (64) |

3.81 (97) |

6.78 (172) |

8.56 (217) |

6.52 (166) |

6.68 (170) |

2.71 (69) |

2.18 (55) |

2.37 (60) |

50.58 (1,285) |

| Source 1: The Weather Channel[57] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration[58] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 386 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,386 | 259.1% | |

| 1900 | 1,983 | 43.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,662 | 34.2% | |

| 1920 | 4,101 | 54.1% | |

| 1930 | 5,269 | 28.5% | |

| 1940 | 6,158 | 16.9% | |

| 1950 | 8,694 | 41.2% | |

| 1960 | 12,849 | 47.8% | |

| 1970 | 12,891 | 0.3% | |

| 1980 | 14,780 | 14.7% | |

| 1990 | 14,716 | −0.4% | |

| 2000 | 15,340 | 4.2% | |

| 2010 | 17,298 | 12.8% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 20,147 | [5] | 16.5% |

| Population 1890-2000.[59] | |||

As of the 2010 census, there were 17,298 people; 6,254 households; and 4,218 families residing in the city.[60] The population density was 377.1 inhabitants per square mile of land (976.7/km2).[61] There were 7,130 housing units[60] at an average density of 155.4 per square mile of land(402.5/km2).[61] Of those who identified themselves with one race, the population was 67.6% White, 23.7% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.1% Asian (0.6% Indian, 0.1% Filipino), 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, and 4.7% from other races; 2.03% were from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 14.7% of the population, including 9.5% of the population who identified as Mexican.[60]

There were 6,254 households, of which 67.4% were families (one or more other people related to the householder by birth, marriage, or adoption), 27.4% consisted of individuals, 35.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.2% were heterosexual married couples living together, 18.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 3.12. Among housing units, 87.7% were occupied and 1.4% were for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use; 63.5% of occupied housing units were owner-occupied and 36.5% were occupied by renters.[60]

The median age was 36.2 years; 25.8% under the age of 18, 9.3% from 18 to 24, 26.0% from 25 to 44, 24.1% from 45 to 64, and 14.8% who were 65 years of age or older. For every 100 males there were 112.6 females. For every 100 males age 18 and over, there were 120.1 females.[60]

According to the American Community Survey (2009-2013), the median income for a household in the city was 44,297, and the median income for a family was 56,009. Among full-time, year-round workers, males had a median income of $39,540 versus $32,076 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,994. About 17.2% of families and 22.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.9% of those under age 18 and 13.3% of those age 65 or over.[60]

The estimated population on April 1, 2014 was 17,637.[62]

Religion

The first two churches built in town, the First Baptist and the First Methodist churches, were constructed on land given by the city founder Jacob Summerlin in 1867. Jacob Summerlin was known as the "King of the Crackers" and owned much of the land located around Bartow.[63] These churches, although not housed in the original buildings, are still extant today. In 1919, more than 8,000 people came to Bartow to hear former baseball star and traveling evangelist Billy Sunday preach, which was twice as much as the population of Bartow and more than the population of the county's largest city Lakeland at the time.[64] As of 2010, there are more than 70 churches within the Bartow area.[65]

Like most of the Bible Belt, Bartow has a high number of people affiliated with evangelical Protestant denominations with over 62% of churchgoers belonging to evangelical denominations.[66][67] According to data published by the Glenmary Research Center in 2000, the denomination which has the largest number of adherents in Bartow is the Southern Baptist Convention with 27%, followed by the Roman Catholic church with 19%.[66] Pentecostal/Charismatic churches are also prominent making up 17% of Bartow's church attendance.[66] The Pentecostal experience known as the Lakeland revival, which attracted controversy for its claims of supernatural healing, was started up the road at the Carpenter's Home Church in Lakeland.[68][69] Other churches which have a presence in Bartow include the United Methodist Church at 9%, and the Episcopal and Lutheran churches with 2% apiece. While there are no synagogues in town for Jewish Bartownians, Temple Emanuel is a conservative synagogue only 12 miles (19 km) away in Lakeland.[70] There are two Muslim mosques and a Hindu temple in the county.[71]

Economy

The economy of Bartow is driven by four sectors: government, mining, agriculture, and tourism. While Bartow's population is less than 20,000, it is shaped by its proximity to several large centers of population. Within a 100-mile (160 km) radius of the center of town, there are close to 8 million people.[31][72]

The dominant force in the economy of Bartow is city, county and state government.[72] As a small city which is the seat of a county with over half a million people, Bartow has an unusually large number of government jobs. In addition to city and county offices, there are also a number of regional, state, and federal offices located within Bartow city limits. Nine of the seventeen largest employers in Bartow are government entities.[73] The largest by far is the Polk County School Board with over 12,000 employees. Other county entities which employ many people in the Bartow area include the county commission, the sheriff's department, the clerk of court, the tax collector, and the property appraiser.[73] The Florida Department of Transportation District One office is located in Bartow and is responsible for southwest Florida's transportation needs.[74]

There are several large businesses with headquarters elsewhere which were founded in Bartow. The large international law firm of Holland & Knight was founded in Bartow in 1929.[75] What eventually become the large Burdines and Sons department store chain was founded in Bartow in 1896 as Payne and Burdines.[76] A couple years after opening his store, William M. Burdines opened a store in Miami and relocated his operations there.[76]

Phosphate mining has been a major player in Bartow's economy since the discovery of phosphate rock in 1881.[31] Polk County is part of the Bone Valley which is the richest source of phosphate rock in the world;[31] 75% of the United States's supply and 25% of the world's supply come from the Bone Valley.[31] The largest employer in the phosphate industry is Mosaic which employs over 3,000 people in the area.[73]

In terms of area, Polk County has 600,000 acres (2,400 km2) dedicated to agriculture.[31] According to the US Census of Agriculture, Polk County is the top citrus production county in Florida.[77] Polk County is also ranked second in the state in production of honey and fourth in number of heads of cattle.[77] Since 1997 the new bumper crop in the area is blueberry.[78] From 2000−07 the area has more than doubled its production of blueberries and accounts for more than 35% of the state's production of the fruit.[77] While spring is usually a "dead" time for every other blueberry growing area in North and South America, Polk County blueberries peak from March to May.

Although there are no major tourist attractions in the immediate Bartow area, the city is located less than 50 miles (80 km) from both the Walt Disney World Resort and Busch Gardens Tampa Bay.[41][79] The city is also less than 20 miles (32 km) from Legoland Florida in Winter Haven and Bok Tower Gardens in Lake Wales.[80][81] As a city with many historical sites dating back over 100 years, Bartow is also a point of interest for those interested in historical sites and monuments.[82]

Culture

Annual festivals and other events

There are several annual events in the Bartow area which have a long tradition. Many of these are large events which draw people from other communities to the city such as the Cricket Club Halloween Parade and Carnival held each year since 1942 or the annual Fourth of July Celebration held at Mosaic Park.[83][84] The Bloomin' Arts Festival is an art show held in early March by the Bartow Art Guild.[85] Every February brings the Annual L.B. Brown Festival at the L.B. Brown House on L.B. Brown Avenue (formally Second Avenue).[86] Bartow's discarded natural Christmas trees are piled around a telephone pole for the annual New Year's Eve bonfire, a unique tradition spanning more than seven decades which has sometimes been covered by national media.[87]

The Polk County Arts Alliance based in Bartow is designated the official Art Agency by the county commission and is in charge of furthering the performing arts in the county.[88] The Bartow Performing Arts Series sponsors five performances every year. The Imperial Symphony Orchestra is an ensemble of ninety volunteer musicians throughout the county who perform a dozen or so events every year including a concert "under the stars."[89] The city also has a volunteer band, the Bartow Community Band, which performs several shows a year.[90] On the third Friday of every month, Main Street is blocked off for Friday Fest at 6 p.m. for a night of live music and entertainment, informally known as "Tow Jam" by natives.[91]

Historic buildings and landmarks

The city's Historic Architecture Review Board is responsible for the preservation, enhancement and promotion of historic buildings, landmarks and districts within the city.[92] Three districts in the city, the Bartow Downtown Commercial District, the Northeast Bartow Residential District, and the South Bartow Residential District have been designated as historic districts.[93] New construction within these districts is regulated by the board and they have the power to veto construction which might alter the character of the neighborhood.[92]

While the towering oaks and ever-present azalea bushes which spawned the city's nickname give many of the historic landmarks of the city a distinctive Southern "look and feel", many styles of architecture are represented in Bartow's historic buildings. The South Bartow and Northeast Bartow historic districts are characterized by masonry vernacular and various revival styles, while downtown is dominated by frame vernacular and classical revival styles.[93] Other buildings on the National Register of Historic Places with distinctive architectural styles include the Thompson and Company Cigar Factory built in a Mission Revival Style and the L.B. Brown House built with distinctive Victorian ornamentation.[94] The L.B. Brown House is notable as perhaps the only house still standing in Florida built by a freedman.[94][95] The Old Polk County Courthouse, Bartow's most recognizable symbol seen on its city seal, was built in 1909 in a neoclassical style.[93]

Florida Senator Spessard L. Holland was born in Bartow. His home is located on South Broadway 2 blocks north of Bartow High School. Senator Holland was a founding member of the Holland and Knight Law Firm. The firm's original office was located on South Central Avenue across the street from the Bartow Post Office.

There are several other notable buildings in Bartow which are not on the National Register of Historic Places. The Wonder House at 1075 Mann Road features natural air-conditioning (using rainwater), secluded outdoor bathtubs, and numerous mirrors that let occupants see who is at the door from other parts of the home.[96] The current owners of the Wonder House are restoring it and plan to open a museum. The Thomas Lee Wilson House, also known as the Stanford Inn, at 555 East Stanford Street was the "Sultenfuss Funeral Parlor" in the movie My Girl.[97] The house at 935 South Oak Avenue known as "Windsweep" was the residence used in the movie China Moon.[98]

Sports and recreation

Many of the recreational opportunities in the area are outdoor activities designed to take advantage of the warm subtropical climate. There are eighteen parks in the City of Bartow Department of Parks and Recreation.[99] Mary Holland Park, named after the wife of former Florida governor Spessard Holland, is a 119-acre (0.48 km2) park with three lakes, a playground, an overnight camping area, and a skateboard park.[99] The Bartow Civic Center is a 31-acre (130,000 m2) complex with meeting rooms, concert facilities and a public pool.[99] Bartow Park is a 95-acre (380,000 m2) complex with softball, baseball and soccer fields and a track for remote control cars.[99] The Bartow Golf Course is a par 72, 6,300 yard course designed by renowned golf course architect Donald Ross, with a restaurant and an area for barbecuing.[99]

The Tour de Tow is an annual cycling tour held in September.[100] The Fort Fraser Trail is a 7.7 miles (12.4 km) path leading from Bartow to South Lakeland.[101] The path follows a converted CSX railroad line and is popular with area cyclists, joggers, and in-line skaters.[101] Plans have been made to build a replica of the historic Fort Fraser along the path, as well as adding historical markers.[101] Five picnic areas and six rest shelters are available along the path.[102]

Polk County has over 550 lakes.[103] Most of these lakes were formerly strip mines; they are closed to the public, only 88 of the lakes are open to the public via boat ramp access.[103] The area has a national reputation for largemouth bass fishing and there are tournaments held weekly almost year-round.[104][105] Some of the lakes on the east side of Bartow offer anglers the opportunity to catch 50 largemouth bass a day.[106]

Government and politics

Municipal government

The City of Bartow has a commission-manager form of government. The city commission consists of five commissioners, each elected for a three-year term.[107] The mayor is a member of the city commission elected annually by the commissioners, although traditionally the position is rotated.[107] As of 2021, the mayor of Bartow is Scott Sjoblom. Other commissioners are James F. Clements, Steve Githens, Leo Longworth, and William “Billy” Simpson.[1][108] The city executive powers rest with the city manager, as contracted by the city commission. In 2010, the city's budget was $74.2 million.[109]

Electricity, waste disposal and water are municipal services provided by the city of Bartow to residents in city limits and nearby areas. Bartow is part of the Southwest Florida Water Management District and in times of drought, the city strictly enforces the restrictions set forth by the district.[110] Although it is a private entity outside of the city limits of Bartow, the Bartow Executive Airport is governed and administrated by the city commission which convenes as the Bartow Airport Authority. As of 2016, the Bartow Police Department has five sergeants, twenty officers, three K-9 officers, two school resource officers, two public safety aides, and one parking enforcement specialist, while the Bartow Fire Department has 18 full-time firemen.[111][112] The city of Bartow also operates the Bartow Public library, which was founded in 1897 and has reciprocal borrowing agreements with other public libraries in Polk County.[113]

Federal and state representation

Bartow, as well as the rest of Polk County, is part of the so-called I-4 corridor. The I-4 corridor is seen by political analysts as the most politically competitive part of the state.[114] Polk is considered the most conservative county in the corridor.[115] Even though the majority of the residents of Bartow are members of the Democratic Party, outnumbering the Republican Party in party affiliation (53.3% to 31.7%), voters tend to support Republicans in most state and federal elections.[116] In 2008 Republican presidential candidate John McCain's lead over Democrat Barack Obama (53.6% to 46.5) in the city was larger than that of both the county and state.[117]

All of Bartow's local representation in the state and federal legislatures are members of the Republican Party. Bartow is represented in the state Florida House of Representatives by Ben Albritton.[118] In the Florida Senate, Bartow is represented by Denise Grimsley.[119] In the United States House of Representatives, Bartow is located in Florida's 15th congressional district, and represented by Congressman Dennis A. Ross.

The Florida Department of Citrus has its headquarters in the Bob Crawford Agricultural Center in Bartow.[120]

Education

The schools in Bartow are operated by the Polk County School Board, although several of them predate the establishment of the school board, and were autonomous at one time. Bartow High School, formerly Summerlin Institute, is the oldest high school in the county and one of the oldest high schools in the state of Florida.[29] In 1923 Union Academy, became the first African-American high school in Polk County. Court-ordered integration began in Bartow during the fall of 1969, and the former black high school Union Academy became a middle school.[29] In 1971, Summerlin Institute officially became Bartow High School, a name it had been known as informally at least since the early 1900s. There are currently seven elementary schools and two middle schools which are feeder schools of Bartow High School.[109] Located at the campus of Bartow High School is the International Baccalaureate School of Polk County which offers an academically challenging environment and the Summerlin Academy which offers a military-oriented education.[29]

It is expected that the rapid growth of the Clear Springs development will necessitate the building of at least two elementary schools and a middle school within the next twenty years.[121] As part of this development, a new Polk State College campus called The PSC Advanced Technology Center at Clear Springs is projected to open by 2012. This 20 acres (81,000 m2) campus will be located near the intersection of State Road 60 and 80 Foot Road.[122]

While there are currently no colleges or universities in Bartow, there are several within a 20 mi (32 km) radius of Bartow. The nearest university, University of South Florida Polytechnic is located 6 mi (9.7 km) northwest of city limits in Lakeland on a joint campus with Polk State College.Florida Southern College and Southeastern University are also located in Lakeland.[123] Warner University is located to the east in Lake Wales.[81]

Media

Bartow is part of the Tampa/St. Pete television market, the 13th largest in the country.[124] There are two AM radio stations within the city: WQXM (1460 AM) and WWBF (1130 AM). These stations are part of the local Lakeland/Winter Haven radio market, which is the 94th largest in the country.[125] In addition to the stations in the local market, people in the area have the choice of both Tampa Bay and Orlando area radio stations and as of the 2010 market sweeps several of the most listened to stations in the market are in the Tampa Bay area.

The Polk County Democrat is the only newspaper published within Bartow. It is a semi-weekly paper which began publication in 1931.[126] The dominant daily newspaper is The Ledger out of Lakeland, although the Tampa Tribune, the News Chief out of Winter Haven, Florida and the Orlando Sentinel have some circulation in town.[127]

Transportation

The street grid of Bartow is a typical four quadrant grid with Main Street as the east-west axis and Broadway Avenue as the north-south axis. Broadway is co-signed with U.S. Route 98 in the northern commercial district and leads southward into the center of town before heading into one of the older residential sections of town. Main Street is the old State Road 60 leading into the historic heart of downtown Bartow.[128]

The primary numbered routes going through Bartow are State Road 60 and U.S. Route 17 and U.S. Route 98.[128] State Road 60 is a major state highway leading to both the Gulf and Atlantic coasts and is the major east-west route through town. Originally traveling along Main Street, State Road 60 now follows Van Fleet Drive bypassing the downtown area, and is commonly known as "the 60 Bypass" by locals.[128][129] Heading east on State Road 60 leads to Lake Wales and on to Vero Beach, while westbound leads to Mulberry and eventually Tampa. U.S. 17 is the main north-south route on the east side of town. It is a four lane divided highway leading north to Winter Haven and south to Fort Meade.[128] U.S. 98 is cosigned with U.S. 17 until its intersection with SR 60. Briefly cosigned with State Road 60 until its intersection with Broadway Avenue. US 98 then turns northward onto Broadway Avenue heading towards Lakeland.[128] State Road 570, known as the Polk Parkway, is a toll road located (10 km) north of city limits on U.S. 98. The Polk Parkway provides direct freeway access to Tampa and Orlando via Interstate 4.[130]

The explosive growth expected in the area in the next few decades has created a need for a reexamination of the area's transportation infrastructure. The Central Polk Parkway is a proposed limited access highway that would connect the Polk Parkway with U.S. 17 and State Road 60.[131] The Northern Bartow Connector, which was expected to be completed by 2015 but was shelved as of 2016, is a partial loop around the north part of town connecting U.S. 98 with State Road 60 east of town.[132] However, the portion connecting U.S. 98 and U.S. 17 was completed in 2013.[133]

For aviation needs, Bartow Executive Airport is available. The airport has a VFR control tower, three 5,000 ft runways - including two parallel runways, a restaurant with views of the airfield, and includes an industrial park and warehouse storage.[134] Both Tampa International Airport (TPA) and Orlando International Airport (MCO) are within 60 miles (97 km) driving distance from the center of Bartow.[41][42]

Bartow has its own bus system, the Bartow Shuttle, which runs from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday. The Citrus Connection has buses that serve the Bartow downtown area from Lakeland, and Winter Haven Area Transit serves Bartow from Winter Haven and Fort Meade.[135][136]

Library

The Bartow Public Library is a member of the Polk County Library Cooperative.[137] The library is located at 2150 S. Broadway Ave. Bartow, FL 33830.[138] The library first started May 19, 1897 above Polk County National Bank. After obtaining a Carnegie Grant the public library was opened on February 8, 1915. It moved to the current location in 1998.[137]

Notable people

The city's Chamber of Commerce claims that few cities since Jamestown have produced as many prominent citizens per capita as Bartow, but this is not documented. As it is the county seat, many government officials and politicians have been associated with Bartow since its founding. Perhaps the most notable is Spessard Holland, former Florida governor and U.S. Senator, who governed the state during World War Two and introduced the 24th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which prohibited use of the poll tax in federal elections. Holland had opposed previous civil rights legislation.[139] Spessard L. Holland Elementary, named in his honor, opened in 2009. His predecessor in the U.S. Senate, Charles O. Andrews, also attended school in Bartow.[140] Others who were raised and schooled in Bartow include former Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice Stephen Grimes,[141] former Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris, who had a key role during the 2000 U.S. Presidential election,[142] and former U.S. congressman Adam Putnam.[143]

The most notable military officer from Bartow is four-star general James Van Fleet, who was the commanding officer of the United Nations forces during the Korean War. Other generals associated with the City of Bartow include Albert H. Blanding, who served during World War One, and Confederate General Evander M. Law, who lived for his last forty years in Bartow.[144][145]

Numerous men who became professional athletes were born, lived in or associated with the city of Bartow. Some were born in Polk General Hospital, a public hospital in Bartow which closed in 1995, but most were generally associated with other cities in Polk County.[146] Born in Bartow and raised elsewhere in the county were NFL linebacker Ray Lewis,[147] NBA guard Tracy McGrady,[148] and motocross star James "Bubba" Stewart.[149] Other athletes who were raised and educated in Bartow include former NFL defensive back Ken Riley, former NFL defensive back Marcus Floyd, former Cleveland Indians outfielder Frank Baker, former college wide receiver Lance Leggett,[150] and former NASCAR driver Rick Wilson.[151][152]

Other notable people from Bartow include Lake Eola Park founder Jacob Summerlin, January 2010 Playboy (magazine) Playmate Jaime Faith Edmondson,[153] centenarian Charlie Smith,[154] lynching victim Fred Rochelle, and Ossian Sweet, a physician who challenged the color line in Detroit and was acquitted of murder charges.[155]

See also

References

- "City Officials - Mayor and Commissioners". City of Bartow. 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- "City of Bartow City Officers". City of Bartow. Archived from the original on August 11, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "Florida's 15th Congressional District & Map". govtrack.us. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Home Page, City of Bartow". City of Bartow. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Polk County History". Polk County Historical Association. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Ancient Native". HOTOA. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- "Over the Branch" (PDF). Polk County Historical Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- Rivers, L. "Interaction Between Blacks and Indians". University of South Florida. Archived from the original on March 8, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Interview with Cantor Brown, PhD". University of South Florida. Archived from the original on September 2, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- Brown, C & Jackson, D. "Free Blacks, Red Stick Creeks, and International Intrigue in Spanish Southwest Florida". University of South Florida. Archived from the original on March 9, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Armed Settlement Act Text". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "A look back in time". Mainstreet Bartow. Archived from the original on December 26, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Sheriffs of Polk County". Polk County Sheriff's Office. Archived from the original on January 25, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- "Polk County Courthouse". Florida 10th Judicial Circuit. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- "Cow Hunters and Cattle Barons". State Library and Archive of Florida. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Florida's Role in the Civil War: "Supplier of the Confederacy"". University of South Florida. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Polk County Historical Association Quarterly 6-2003" (PDF). Polk County Historical Association. June 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Timeline of Florida History". State Library and Archives of Florida. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "1900 Census Data" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "1880 Census Data" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- Sawyer, Martha F. (February 17, 1982). "Blount family first settled Bartow". Lakeland Ledger. pp. 6C. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- "Florida Southern's Narrow Gauge Years 1879–1896". taplines.net. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Florida Southern's Narrow Gauge Years 1879–1896". taplines.net. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "History of Bartow High School". Bartow High School. Archived from the original on October 17, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- "Us Census" (PDF). US Census. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- "Polk's Profile". Polk County Government. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "Airport History". Bartow Municipal Airport. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "18,000-Acre Development Near Bartow Awaits Approval". The Ledger. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- "Map of Phosphate Mining Areas" (PDF). Florida Department of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- "1970 Census Data" (PDF). US Census Bureau. pp. 19–21. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "Florida's Phosphate Deposits". Florida Department of State. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- "Clear Springs Construction a step closer". The Ledger. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "Clear Springs Plan moving forward". Polk county Democrat. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "18,000 Acre Development near Bartow Awaits Approval". The Ledger. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "PolkVision/Our Region". PolkVision. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Distance from Bartow to Tampa". indo.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Distance from Bartow to Orlando". indo.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Publication 04-39-087" (PDF). University of Florida. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Map of Bartow, Lakeland, Winter Haven showing 'triangle'". google.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Peace River Watershed". Florida Dept. of Environmental Protection. Archived from the original on October 15, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Florida's Geological History". University of Florida. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- "MLRAs in FL". USDA. Archived from the original on October 8, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "Fort Meade Series". National Cooperative Soil Survey. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "Web Soil Surbey". USDA. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna. November 6, 2008. Archived from the original on September 6, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1134". USGS. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Gray, W. & Klotzbach, P. "Forecast Of Atlantic Hurricane Activity For Oct. 2004". Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- "2004 Hurricane Season Taught Polk to Stay Vigilant". The Ledger. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- NASA (2007). "Staying Safe in Lightning Alley". NASA. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- "Florida hazardous weather by day" (PDF). NOAA. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- "Snow, Sleet Pelt Frigid Polk". The Ledger. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- "Monthly Averages for Bartow, FL". The Weather Channel Interactive, Inc. 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- "Climatography of the United States No. 81 (1971–2000)" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. February 2002. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- "Census Of Population And Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- "U.S. Census website". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- "Florida: 2010 — Population and Housing Unit Counts (CPH-2-11)" (PDF). census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. September 2012. p. 70 (36 Florida). Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- "Florida Population Estimates for Counties and Municipalities April 1, 2014" (PDF). Florida LegislativeOffice of Economic and Demographic Research. October 2014. p. 9. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- "First Methodist Church History". First Methodist Church. March 2003. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "Billy Sunday" (PDF). Polk County Historical Association. March 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Our Community Churches". Bartow Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on September 12, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- Harpool, A. "Religion in Polk". The Association of Religious Data Archives. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Delineating the Two Florida's" (PDF). University of Florida. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- Rhee, Alice (May 29, 2008). "Revivalist Claims Hundreds of Healings". MSNBC. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- "Faith-Healing 'Outpouring' Overflows Venue". TheLedger.com. April 25, 2008. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- "Temple Emanuel History" (PDF). Temple Emanuel. October 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Ledger Religion in Polk". Lakeland. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Economy of Bartow". Bartow Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "Major Employers". Bartow Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "FDOT District One". Florida Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on August 26, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "Biography of Stephen Grimes". Holland & Knight. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "History of Burdines" (PDF). Polk County Historical Association. June 1996. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Polk County Ag Statistics". Polk County Farm Bureau. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- Townsend, B. "Clear Springs Sees Gold In Blueberries". Tampa Bay Online. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "Distance from Bartow to Lake Buena Vista, FL". indo.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Distance from Bartow to Winter Haven". indo.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Distance from Bartow to Lake Wales". indo.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Florida's History Through Its Places, Bartow". Florida Department of State. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- "Bartow Halloween Parade is Oct. 30". The Ledger. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "Bartow Plans July 4 Bash". The Ledger. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "South Polk: Bloomin' Arts Show Winners Announced". The Ledger. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- "L.B. Brown events". Neighborhood Improvement Corporation of Bartow, Inc. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- "Bartow's Traditional Tree Burning Tonight". The Ledger. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- "Polk Arts Alliance Home Page". Polk Arts Alliance. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "Imperial Symphony Orchestra". The Ledger. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "The Civic Center". City of Bartow. Archived from the original on November 7, 2006. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "Bartow's Friday Fest 'Tow Jam". The Ledger. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "Historic Architecture Review Board". City of Bartow. Archived from the original on November 7, 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- "Polk County Historic Districts". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- "Historic L.B. Brown House". lbbrown.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "L.B. Brown House". lbbrown.com. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "The Wonder House". The Ledger. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "The Stanford Inn". The Stanford Inn. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "Florida Movies". The Ledger. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Bartow Area Parks & Recreation Facilities". Bartow Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Cycling". Bartow Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "Grand Opening for Fort Fraser Trail Coming Up". The Ledger. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- "Ft. Fraser Trail". Bartow Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- "Polk County Lake Facts". The Ledger. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- "Florida Largemouth Bass - "Battle With The Best"". American Chronicles. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- "Upcoming Tournaments". The Ledger. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- "Mining Clear Springs Lunkers". Bassmaster Magazine/espn.go.com. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- "Bartow City Government". Bartow Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Mayor and City Commission". City of Bartow, FL. City of Bartow, FL. November 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- "Guide to Polk, Bartow". The Ledger. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- "Florida Water Management Districts". State of Florida. Archived from the original on September 20, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- "Bartow Police Department". City of Bartow. Archived from the original on November 7, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Bartow Fire Department". City of Bartow. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- "Bartow Library". City of Bartow. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "As I-4 Corridor goes so goes Florida". The Washington Times. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Candidates scramble to claim I-4 corridor". The Ledger. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Voter Registration Statistics, Bartow Precincts 502-509". Polk County Supervisor of Elections. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "2008 Presidential Election Results, BartowPrecincts (502-509)". Polk County Supervisor of Elections. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Polk County District Map" (PDF). Florida State House. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "District 21 Map". Florida State Senate. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Contact" (Archive). Florida Department of Citrus. Retrieved on September 13, 2015. "Physical Address Bob Crawford Agricultural Center 605 E. Main Street Bartow, FL 33830"

- "First Phase of Clear Springs To Include 10,000 Homes, Town Center Shopping Area". The Polk County Democrat. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "Polk state college advanced technology center at clear springs". Polk State College. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- "Distance from Bartow to Lakeland". indo.com. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- "Top Nielsen Markets". TV By the Numbers. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Arbitron Markets". Arbitron. Archived from the original on October 16, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Polk County Democrat". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "The Ledger Publishers, 1996–Present". Cornell University. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- "Map of Bartow, FL". google maps. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- "Assessment, Accountability & Evaluation" (PDF). Polk County. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Polk Parkway". Florida's Turnpike Authority. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "Proposed Central Polk Parkway Plans Being Sharpened". The Ledger. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- "County OKs Road for Bartow Connector Route". The Ledger. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- "Editorial: Finish the Bartow Northern Connector First". ocala.com. Ocala StarBanner. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "Airport diagram". Bartow Municipal Airport. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- "Buses, Trains, Airports Give Residents Myriad Transportation Choices". The Ledger. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Transit Today". Polk Transit Authority. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- http://www.cityofbartow.net/index.aspx?page=318

- https://pclc.ent.sirsi.net/client/en_US/bartow

- "A Guide to the Spessard L. Holland Papers". University of Florida. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- "ANDREWS, Charles Oscar". congress.gov. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- "Justice Stephen H. Grimes". Florida Supreme Court. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Women in Congress:Katherine Harris". house.gov. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- "Congressman Adam H. Putnam". Congressional Website of Adam Putnam. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Evander Law". History Channel. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "The Great Floridians 2000 Program". myflorida's history website. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2010.

- "Eight Hospitals Took Care Of Residents". The Ledger/bluetoad.com. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "Ray Lewis NFL Bio". NFL. Archived from the original on October 12, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- "Tracy McGrady, basketball-reference.com". basketball-reference.com. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- "James Stewart Bio". Motorcycle USA. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "Lance Leggett bio". hurricanessports.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2010.

- "Polk's Former Pros Have No Regrets". The Ledger. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "Where is ... Rick Wilson?". NASCAR.com. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "Jaime Faith Edmondson From The Amazing Race in Playboy". daemonstv.com. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- "Gerontology: Secret of Long Life". Time Magazine. July 14, 1967. Archived from the original on October 15, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- "Sweet, Ossian (1895-1960)". blackpast.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2010.