Chula Vista, California

Chula Vista (/ˌtʃuːlə ˈvɪstə/; Spanish for '"beautiful view"')[11][12][lower-alpha 1] is the second-largest city in the San Diego metropolitan area, the seventh largest city in Southern California, the fifteenth largest city in the state of California, and the 75th-largest city in the United States. The population was 243,916 as of the 2010 census,[9] and the estimated population as of 2019 is 274,492.[10] Located about halfway—7.5 miles (12.1 km)—between the two downtowns of San Diego and Tijuana in the South Bay, the city is at the center of one of the richest culturally diverse zones in the United States. Chula Vista is so named because of its scenic location between the San Diego Bay and coastal mountain foothills.

Chula Vista, California | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Chula Vista | |

.jpg.webp) _(cropped).jpg.webp) .jpg.webp) Clockwise: Chula Vista City Hall; Otay Ranch; Saint Piux X Church | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nicknames: | |

| |

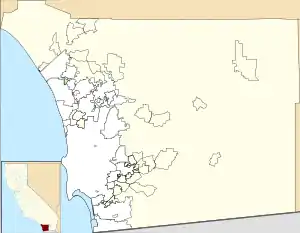

Chulavista Location within San Diego County  Chulavista Location within California  Chulavista Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 32°37′40″N 117°2′53″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Diego |

| Incorporated | November 28, 1911[3] |

| Named for | Spanish for "beautiful view" |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • City Council[4] | Mayor Mary Casillas Salas John McCann Jill Galvez Steve Padilla Mike Diaz |

| • City manager | Gary Halbert[5] |

| Area | |

| • City | 52.10 sq mi (134.93 km2) |

| • Land | 49.64 sq mi (128.56 km2) |

| • Water | 2.46 sq mi (6.36 km2) 4.73% |

| Elevation | 66 ft (20 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 243,916 |

| • Estimate (2019)[10] | 274,492 |

| • Rank | 2nd in San Diego County 15th in California 75th in the United States |

| • Density | 5,529.76/sq mi (2,135.05/km2) |

| • Metro | San Diego–Tijuana: 5,105,768 |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 91909–91915, 91921 |

| Area code(s) | 619 |

| FIPS code | 06-13392 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1660481, 2409461 |

| Website | www |

The area, along with San Diego, was inhabited by the Kumeyaay before contact from the Spanish, who later claimed the area. In 1821, Chula Vista became part of the newly declared Mexican Empire, which reformed as the First Mexican Republic two years later. California became part of the United States in 1848 as a result of the Mexican–American War and was admitted to the union as a state in 1850.

Founded in the early 19th century and incorporated in October 1911, fast population growth has recently been observed in the city. Located in the city is one of America's few year-round United States Olympic Training centers, while popular tourist destinations include Aquatica San Diego, North Island Credit Union Amphitheatre, the Chula Vista marina, and the Living Coast Discovery Center.[15]

History

Early history

Fossils of aquatic life, in the form of a belemnitida from the Jurassic, have been found within the modern borders of Chula Vista.[16] It is not until the Oligocene epoch that land life fossils have been found;[16][17] although Eocene epoch fossils have been found in nearby Bonita.[16] It is not until 10,000 years ago that human activity has been found within the modern borders of Chula Vista, primarily in Otay Valley of the San Dieguito people.[16] The oldest site of human settlement within the modern boundaries of Chula Vista, was named Otai by the Spanish in 1769, and had been occupied as far back as 7,980 years ago.[18] Another place where humans first settled within the modern boundaries of Chula Vista was at the Rolling Hills Site, which dates back to 7,000 years ago.[18]

In 3000 BCE, people speaking the Yuman (Quechan) language began moving into the region from the Lower Colorado River Valley and southwestern Arizona portions of the Sonoran desert. Later the Kumeyaay tribe came to populate the land, on which the city sits today, and lived in the area for hundreds of years.[19] The Kumeyaay built a village known as Chiap (or Chyap) which was located by mudflats at the southern end of South Bay.[20]

In 1542 CE, a fleet of three Spanish Empire ships commanded by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, sailed into San Diego Harbor. Early explorations by Spanish conquistadors, such as these, led to Spanish claims of the land. The village of Chiap (known to the Spanish as La Punta) became a center of a Kumeyaay revolt against the Spanish in 1775, which was later abandoned by 1776.[21] The historic land on which Chula Vista sits became part of the 1795 land grant known as Rancho del Rey or The King's Ranch. The land eventually was renamed Rancho de la Nación.[19]

After Mexico became independent from Spain, what is now Chula Vista became part of Alta California.[12] Beginning in 1829, the land that is now Chula Vista was divided among Rancho Janal, Rancho Otay, Rancho de la Nación and Rancho La Punta; these were owned by José María Estudillo, José's sister Maria, John (Don Juan) Forster, and Santiago E. Argüello respectively.[22]

During the Mexican–American War, California was claimed by the United States, regardless of the California independence movement that had briefly swept the state. Though California was now under the jurisdiction of the United States, land grants were allowed to continue in the form of private property.[19] In 1873, the United States Army built a telegraph line between San Diego and Fort Yuma which ran through Telegraph Canyon in Chula Vista;[22][23] its construction was under the command of Captain George F. Price of the 5th Cavalry Regiment out of Camp McDowell.[24] In the 1870s and 1880s mining was done on Rancho Janal.[25]

The San Diego Land and Town Company developed lands of the Rancho de la Nación for new settlement. The town began as a five thousand acre development, with the first house being erected in 1887; by 1889, ten houses had been completed.[26] Around this time, the lemon was introduced to the city, by a retired professor from the University of Wisconsin.[27] Chula Vista can be roughly translated from Spanish as "beautiful view";[19] the name was suggested by Sweetwater Dam designer James D. Schulyer.[28]

The 1888 completion of the dam allowed for irrigation of Chula Vista farming lands. Chula Vista eventually became the largest lemon-growing center in the world for a period of time.[19] As of February 2019, the oldest surviving buildings in Chula Vista originate from around this time, including the Barber house, and the Cordrey house.[29] Additionally, the Coronado Belt Line Railroad was built through Chula Vista, connecting Hotel Del Coronado with the National City, where Southern California Railroad terminated.[30] Another railroad built through Chula Vista, was the National City and Otay Railroad, which was routed down Third Avenue.[31] During the depression at the end of the century, industrial employment in Chula Vista was limited to the La Punta Salt Works and packing houses.[32]

20th century

The citizens of Chula Vista voted to incorporate on October 17, 1911. The State approved the city's incorporation in November.[19] One of its first city council members was a former Clevelandite Greg Rogers, who was also a leader of the Chula Vista Yacht Club.[33] The yacht club would the first on the West Coast to build race specific boats, which resulted in a uniquely designed sloop.[34] In 1915, a Carnegie Library was built on F Street.[35] In the 1910s, Chinese, Filipino, and Mexican farm laborers worked the fields within the city, with most commuting in from Downtown San Diego and Logan Heights.[36]

In January 1916, Chula Vista was impacted by the Hatfield Flood, which was named after Charles Hatfield, when the Lower Otay Dam collapsed flooding the valley surrounding the Otay River;[37] up to fifty people died in the flood.[38] Later in 1916, the Hercules Powder Company opened a 30-acre bayfront site, now known as Gunpowder point, which produced substances used to make cordite, a gun propellant used extensively by the British Armed Forces during World War I.[12] In 1920, the San Diego Country Club opened in Chula Vista, with its clubhouse designed by Richard Requa who had previously worked on the California Pacific International Exposition.[39] In 1925, aviation began in Chula Vista, with the Tyce School of Aviation, operating the Chula Vista Airport.[40] In 1926, the salt works purchased Rancho Janal and grew barley and lima beans.[22]

Although the Great Depression affected Chula Vista significantly, agriculture still provided considerable income for the residents. In 1931, the lemon orchards produced $1 million in revenue and the celery fields contributed $600,000.[19] Japanese American farms played a significant roll in developing new crops outside of lemons, especially celery.[41] In the 1930s, led by Chris Mensalvas, Filipino and Mexican farm workers went on strike against the celery farms.[42] To the east, on land that use to be Rancho Janal, dairy farming and cattle farming was done on over 4,000 acres.[43] By the end of the 1930s, the city's population of over 4,000 residents were mostly Caucasians, with small populations of Japanese and Mexican Americans.[44] Prior to World War II, anti-Japanese sentiment had existed in Chula Vista, due to competition between Japanese farmers and White farmers, however an association was formed which decreased those sentiments.[45]

In November 1940, the city purchased the Chula Vista Airport for Rohr Aircraft.[46] The relocation of Rohr Aircraft Corporation to Chula Vista in early 1941, just months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, changed Chula Vista. The land never returned to being orchard groves again.[19] At the Rohr factory, the 11,000 employees worked on power units for the Consolidated B-24 Liberator.[47] In 1945, The Vogue Theater opened.[48]

Due to Executive Order 9066 the Japanese Americans who lived in Chula Vista were sent to Santa Anita Racetrack then the Poston War Relocation Center.[49] One of those Japanese Americans from Chula Vista was Joseph K. Sano, who was an air corps veteran of World War I, and a member of the American Legion;[50] during World War II, Sano served in the Military Intelligence Service Language School at the University of Michigan.[51] In 1944, the state of California attempted to seize land in Chula Vista owned by Kajiro Oyama, a legal Japanese resident who was then interned in Utah. Oyama was correctly charged with putting the property in his son Fred's name with the intent to evade the Alien Land Law because Fred was a native-born citizen. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court as Oyama v. California where the court found that Kajiro's equal protection rights had been violated.[52]

The population of post-World War II Chula Vista tripled from 5,000 residents in 1940 to more than 16,000 in 1950.[19] After the war, many of the factory workers and thousands of servicemen stayed in the area resulting in the huge growth in population. The last of the citrus groves and produce fields disappeared as Chula Vista became one of the largest communities in San Diego County.[19] In 1949, the city limits of Chula Vista expanded for the first time.[53] Due to the construction of the Montgomery Freeway the Arguello Adobe of Rancho La Punta was demolished.[54] In 1955, the Big Ski Drive-In opened;[55] until it closed in 1980, it was one of the largest drive-in theaters in the nation.[56] By the 1960s, Chula Vista continued its expansion with the annexation of part of Bonita.[57] That same decade, Filipinos and Mexicans began to move into Chula Vista in significant numbers;[58] these included Filipino navy veterans.[59] In 1963, Chula Vista became the second largest city in San Diego County.[60] From 1960 to 2013, the South Bay Power Plant, a 700 megawatt four boiler plant, occupied 115 acres (47 ha) of the Chula Vista waterfront.[61]

In 1985, Chula Vista made the largest annexation in California history, which included the neighborhoods of Castle Park and Otay.[62] In January 1986, Chula Vista annexed the unincorporated community of Montgomery, which had previously rejected annexation in 1979 and 1982. At the time of the annexation the community was virtually surrounded by its larger neighbor.[63] Later, San Diego gave way, allowing Chula Vista to annex the Otay River Valley, which was opposed by residents in Otay Mesa & Nestor.[64] Over the next few decades, Chula Vista continued to expand eastward. Plans called for a variety of housing developments such as the Eastlake, Rancho del Rey, and Otay Ranch, neighborhoods.[12] During this expansion a walrus fossil was found, of an extinct species of toothless Valenictus, after the species was named for the city.[65] The quick expansion east of Interstate 805 was not embraced by all of the cities residents, leading to advocacy that new housing developments be built with parks, schools, and emergency services.[62] In 1991, Chula Vista elected its first female mayor, Gayle McCandliss, who died from cancer a few weeks after being elected.[66] In 1995, the United States Olympic Committee opened an Olympic Training Center in Eastlake on donated land;[67] it is the USOC's first master-planned facility and is adjacent to Lower Otay Reservoir.[68] In the last decade of the century, a desalinization plant opened to process water from wells along the Sweetwater River;[69] it was expanded less than two decades later,[70] which included a pumping station built in Bonita.[71]

Camp Otay/Weber

During World War I and II The army maintained a base on what is now the corner of Main Street and Albany Avenue. It initially served as a border post during World War I, and was reestablished in December 1942. It was home to the 140th Infantry Regiment, 35th Infantry Division.[72] The regiment conducted war games against the Camp Lockett based 10th Cavalry, and were defeated.[73] The base was closed in February 1944, and the division went on to see combat in the European theater. All traces of the post have since been removed.[72]

21st century

In 2003, Chula Vista had 200,000 residents and was the second-largest city in San Diego County.[74] That year, Chula Vista was the seventh fastest growing city in the nation, growing at a rate of 5.5%, due to the communities of Eastlake and Otay Ranch.[75] Chula Vista is growing at a fast pace,[12] with major developments taking place in the Otay Valley near the U.S. Olympic Training Center and Otay Lake Reservoir. Thousands of new homes have been built in the Otay Ranch, Lomas Verdes, Rancho Del Rey, Eastlake and Otay Mesa areas.[76] In mid-2006, officials from Chula Vista and the San Diego Chargers met to potentially discuss building a new stadium that would serve as the home for the team;[77] yet in June 2009, the Chargers removed Chula Vista as a possible location for a new stadium.[78] The South Bay Expressway, a toll-road extension of State Route 125, opened on November 19, 2007.

As a result of the Mexican Drug War, many Mexicans from Tijuana began to immigrate to Chula Vista.[79] Being in close proximity to Tijuana, however, has led to some drug war activity within Chula Vista.[80] Yet in 2009, Chula Vista—along with nine other second-tier metropolitan area cities such as Hialeah, Florida and California's own Santa Ana—was ranked as one of the most boring cities in America by Forbes magazine, citing the large population but rare mentions of the city in national media.[81]

In 2013, Forbes called Chula Vista the second fastest growing city in the nation, its having recovered from the slowdown during the Great Recession, which saw the city lead the nation in having the highest mortgage default rate.[82] In 2014, a survey conducted at the request of the city found that the majority of San Diegans surveyed had a negative perception of the city.[83] By 2015, there were over 31,000 Filipino Americans living in Chula Vista;[84] they make up the majority of the 48,840 Asian Americans who live in Chula Vista.[12][85] In 2017, Chula Vista purchased the Olympic Training Center and renamed it to Elite Athlete Training Center; the United States Olympic Committee plans to continue to use the facility and pay rent to the city.[86] That same year, a post office in the Eastlake neighborhood was renamed Jonathan "J.D." De Guzman Post Office Building, in honor of a city resident who died while a San Diego Police Department officer in 2016;[87] having immigrated from the Philippines in 2000,[88] De Guzman was active in his community in Chula Vista, and went on to serve as a police officer for 16 years until his death.[89]

The number of reported calls to the Chula Vista Police about issues regarding homeless individuals have increased from 2004 to 2014, with Chula Vista having the largest population of homeless individuals in the South Bay.[90] In 2016, it was estimated that there were about 500 homeless individuals in Chula Vista.[91] Due to the increase in homeless population, Chula Vista, and other neighboring cities began to pass ordinances on recreational vehicles, and other large vehicles, resulting in the number of homeless individuals within the city.[92] By 2018, the number of homeless individuals in Chula Vista was down to 367.[93]

In 2018, a proposal was made to develop Rohr Park into something similar to Griffith Park in Los Angeles.[94] A development plan is to develop the bayfront.

Geography

Owning up to its Spanish name origins - beautiful view - Chula Vista is located in the South Bay region of San Diego County, between the foothills of the Jamul and San Ysidro Mountains (including Lower Otay Reservoir) and San Diego Bay on its east and west extremes, and the Sweetwater River and Otay River at its north and south extremes.[95] The geography of Chula Vista is impacted by the La Nacion and Rose Canyon Fault zones;[96] it has moved rocks from Pleistocene and younger eras.[97] Yet, as late as 13,000 years ago, soils in the Rancho del Rey area have been unaffected by fault activity.[98]

Chula Vista is the second largest city, by area, within San Diego County.[99] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city covers an area of 52.1 square miles (135 km2), 49.6 square miles (128 km2) of it land, and 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2) or 4.73% of it water.

Ecological preserves

Chula Vista has within its city limits the Sweetwater Marsh unit of the San Diego Bay NWR.[100] It also maintains several city maintained open space areas.[101]

West Chula Vista

The original Chula Vista encompasses the area west of Hilltop Drive and north of L Street.[12] The community of Montgomery was annexed by the city, after several failed attempts, in 1986;[63] The community consists of most of the area south of L Street, west of Hilltop Drive and north of San Diego's city limit.[12] Unlike East Chula Vista, West Chula Vista does not have Mello-Roos, which has been suggested to have led to those not living in West Chula Vista to develop a separate civic identity.[102]

East Chula Vista

Beginning in the late 1980s the planned communities of Eastlake, Otay Ranch, Millenia, and Rancho del Rey began to develop in the annexed areas east of Interstate 805 and California State Route 125. These communities expanded upon the eastern annexations of the 1970s, including the area around Southwestern College.[12] In 1986, Eastlake began to be built.[22] In 1989, Rancho del Rey was established.[103] In 1999, Otay Ranch began to be built on 23,000 acres.[104]

In the years around 2008 thousands of Tijuana's elite bought houses in and moved to Eastern Chula Vista escaping violence, kidnapping and other crime taking place during that period in the Mexican metropolis only a few miles away. The Los Angeles Times wrote, “So many upper-class Mexican families live in…Eastlake…and Bonita…that…the area is becoming a gilded colony of Mexicans, where speaking English is optional and people can breathe easy cruising around in their Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs."[105] In late 2018, a new Rapid bus route was created, taking passengers from the Otay Mesa Port of Entry, through Eastern Chula Vista, and then into Downtown San Diego.[106]

Climate

Like the rest of lowland San Diego County, Chula Vista has a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSh/BSk), with Mediterranean characteristics, though the winter rainfall is too low and erratic to qualify as an actual Mediterranean climate.[107]

| Climate data for Chula Vista, California (1981−2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 68.5 (20.3) |

68.1 (20.1) |

68.1 (20.1) |

69.4 (20.8) |

70.1 (21.2) |

72.0 (22.2) |

75.9 (24.4) |

77.8 (25.4) |

78.0 (25.6) |

75.7 (24.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

67.4 (19.7) |

71.9 (22.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 45.8 (7.7) |

47.5 (8.6) |

50.3 (10.2) |

53.0 (11.7) |

57.5 (14.2) |

60.6 (15.9) |

64.5 (18.1) |

65.6 (18.7) |

63.2 (17.3) |

57.9 (14.4) |

50.2 (10.1) |

45.3 (7.4) |

55.1 (12.8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.87 (47) |

2.30 (58) |

1.70 (43) |

0.66 (17) |

0.09 (2.3) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.14 (3.6) |

0.49 (12) |

0.98 (25) |

1.31 (33) |

9.64 (245) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.0 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 32.4 |

| Source: NOAA[108] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1920 | 1,718 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,869 | 125.2% | |

| 1940 | 5,138 | 32.8% | |

| 1950 | 15,927 | 210.0% | |

| 1960 | 42,034 | 163.9% | |

| 1970 | 67,901 | 61.5% | |

| 1980 | 83,927 | 23.6% | |

| 1990 | 135,163 | 61.0% | |

| 2000 | 173,556 | 28.4% | |

| 2010 | 243,916 | 40.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 274,492 | [10] | 12.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[109] | |||

| Year | Population (pop.) | Change in pop. (raw) | Change in pop. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 243,916[9] | +70,360 | +40.5% |

| 2000 | 173,556[110] | +38,393 | +28.4% |

| 1990 | 135,163[111] | +51,236 | +61.0% |

| 1980 | 83,927[112] | +16,026 | +23.6% |

| 1970 | 67,901[112] | +25,867 | +61.5% |

| 1960 | 42,034[12] | +26,107 | +163.9% |

| 1950 | 15,927[113] | +10,789 | +209.9% |

| 1940 | 5,138[12] | +1, 269 | +32.7% |

| 1930 | 3,869[12] | +2,151 | +125.2% |

| 1920 | 1,718[12] | +1,068 | +164.3% |

| 1910 | 650[12] | - | - |

2010

The 2010 United States Census[114] reported that Chula Vista had a population of 243,916. The population density was 4,682.2 people per square mile (1,807.8/km2). The racial makeup of Chula Vista was 130,991 (53.7%) White, 11,219 (4.6%) African American, 1,880 (0.8%) Native American, 35,042 (14.4%) Asian, 1,351 (0.6%) Pacific Islander, 49,171 (20.2%) from other races, and 14,262 (5.8%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 142,066 persons (58.2%).

The Census reported that 242,180 people (99.3% of the population) lived in households, 656 (0.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 1,080 (0.4%) were institutionalized.

There were 75,515 households, out of which 36,064 (47.8%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 42,153 (55.8%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 12,562 (16.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 4,693 (6.2%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 3,720 (4.9%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 502 (0.7%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 12,581 households (16.7%) were made up of individuals, and 4,997 (6.6%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.21. There were 59,408 families (78.7% of all households); the average family size was 3.60.

The population was spread out, with 68,126 people (27.9%) under the age of 18, 24,681 people (10.1%) aged 18 to 24, 70,401 people (28.9%) aged 25 to 44, 56,269 people (23.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 24,439 people (10.0%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.2 males.

There were 79,416 housing units at an average density of 1,524.5 per square mile (588.6/km2), of which 43,855 (58.1%) were owner-occupied, and 31,660 (41.9%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.4%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.5%. 143,330 people (58.8% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 98,850 people (40.5%) lived in rental housing units.

Late 20th century

In 2000, the city's population was 173,556. The racial make up of the city during the 2000 census was 55.1% White, 22.1% Other, 11% Asian, 5.8% of two or more races, 4.6% African American, 0.8% Native American, and 0.6% Pacific Islander. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 49.6%. Of these individuals, 28.7% were under the age of 18.[110][115]

In 1990, the city's population was 135,163. The racial make up of the city during the 1990 census was 67.7% White, 18.1% Other, 8.2% Asian, 4.5% African American, 0.6% Pacific Islander, and 0.6% Native American. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 37.2%. Of these individuals, 26% were under the age of 18.[111]

In 1980, the city's population was 83,927.[112] The racial make up of the city during the 1980 census was 83.1% White, 7.9% "Race, n.e.c.", 6.1% Asian and Pacific Islander, 2.1% African American, and 0.7% Native American. Persons of "Spanish Origin" made up 46.6% of the population.[116]

Economy

Chula Vista maintains a business atmosphere that encourages growth and development.[117] In the city, the small business sector amounts for the majority of Chula Vista's business populous.[117] This small business community is attributed to the city's growth and serves as a stable base for its economic engine.[117]

Tourism

Tourism serves as an economic engine for Chula Vista. The city has numerous dining, shopping, and cinema experiences.[118] As with many California cities, Chula Vista features many golf courses.[119] Some of the city's notable attractions included the Chula Vista Nature Center, Otay Valley Regional Park, North Island Credit Union Amphitheatre, OnStage Playhouse, the Chula Vista Marina, Aquatica San Diego, and the U.S. Olympic Training Center.[120] The Nature Center is home to interactive exhibits describing geologic and historic aspects of the Sweetwater Marsh and San Diego Bay. The center has exhibits on sharks, rays, waterbirds, birds of prey, insects, and flora.[120] Otay Valley Regional Park is located partially within Chula Vista, where it covers the area of a natural river valley.

The marina at Chula Vista is located in South Bay including multiple marinas and being home to the Chula Vista Yacht Club. Sports fishing and whale watching charters operate the regional bay area. The Olympic Training Center assists current and future Olympic athletes in archery, rowing, kayaking, soccer (association football), softball, field hockey, tennis, track and field, and cycling.[120]

Chula Vista Center is the city's main shopping mall, opened in 1962.

Top employers

According to the city's 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[121] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sweetwater Union High School District | 4,133 |

| 2 | Chula Vista Elementary School District | 3,680 |

| 3 | Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center | 2,287 |

| 4 | Rohr Inc./Goodrich Aerospace | 1,928 |

| 5 | Southwestern College | 1,743 |

| 6 | Walmart | 1,323 |

| 7 | City of Chula Vista | 1,208 |

| 8 | Scripps Mercy Hospital Chula Vista | 1,073 |

| 9 | Aquatica | 698 |

| 10 | Costco | 674 |

Culture

Chula Vista is home to OnStage Playhouse, the only live theater in South Bay, San Diego.

Other points of interest and events include the Chula Vista Nature Center,[122] the J Street Harbor,[123] and the Third Avenue Village.[124] Downtown Chula Vista hosts a number of cultural events, including the famous Lemon Festival, Starlight Parade, and Chula Vista Rose Festival. North Island Credit Union Amphitheater is a performing arts theatre that was the areas first major concert music facility.[125] OnStage Playhouse produces community theatre productions.[120][126]

Sports

Chula Vista is the site of the Chula Vista Elite Athlete Training Center, formerly the Olympic Training Center.[127] The U.S. national rugby team practices at the OTC. Chula Vista is also home to Chula Vista FC which gained national attention with its 2015 Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup run.[128]

In 2009 Parkview Little League won the 2009 Little League World Series, earning the nickname "The Blue Bombers".

In 2013 Eastlake Little League won the American Championship at the 2013 Little League World Series.

Government

Municipal government

The City of Chula Vista is a California charter city operating under the council–manager government form. The council is composed of four members elected from geographic districts and led by a mayor who is elected by the entire city. The city council serves as the legislative body of the city, and it appoints a city manager to serve as chief administrator.[129] Presently the city council is led by Mayor Mary Casillas Salas. It has four other members: John McCann (District 1),[lower-alpha 2] Jill Galvez (District 2),[lower-alpha 3] Stephen Padilla (District 3),[lower-alpha 4] and Mike Diaz (District 4).[lower-alpha 5][4] Each city council member is elected from a single-member district. Elections follow a two-round system. The first round of the election is called the primary election. The top-two candidates in the primary election advance to a runoff election, called the general election. Write-in candidates are only allowed to contest the primary election and are not allowed in the general election. Council members are elected to four-year terms, with a two-term limit.[130] City council seats are all officially non-partisan by state law, although most members identify a party preference. The most recent general election was held in November 2018 for districts 1 and 2. The next elections for these seats will be held in 2022. General elections for districts 3 and 4 were last held in November 2016. The next election for these seats will be in 2020.

According to the city's most recent Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the city's various funds had $322.9 million in Revenues, $287.5 million in expenditures, $1.232 billion in total assets, $258.6 million in total liabilities, and $181.0 million in cash and investments.[131]

As of 2018 the city's police and fire departments are understaffed, and ambulance services are contracted out to American Medical Response.[132]

Politics

Following 2011 redistricting by the California Citizens Redistricting Commission, the city's federal representation was split between the 51st and 53rd congressional districts.[133] In the California State Senate, the city remained entirely in the 40th Senate district. However, in the California State Assembly, it was split between the 79th and 80th Assembly districts.[134]

At the state and federal levels, Chula Vista is represented entirely by Democrats. In the State Senate, Chula Vista is represented by Democrat Ben Hueso.[135] In the Assembly, it is represented by (vacant) (79th district) and Democrat Lorena Gonzalez (80th district).[136] In the United States Senate, it is represented by Dianne Feinstein and Kamala Harris, and in the United States House of Representatives, it is represented by Democrat Juan Vargas (51st district) and Democrat Sara Jacobs (53rd district).[137]

As of January 2013, out of the city's total population, 114,125 are registered to vote, up from 103,985 in 2009; the three largest registered parties in the city are the Democratic Party with 47,986, Republican Party with 31,633, and Decline to State with 29,692.[138] In a survey conducted by The Bay Area Center for Voting Research in 2004, it found that Chula Vista had a 50.59% conservative vote compared to a 49.41% liberal vote.[139]

Education

The Sweetwater Union High School District, headquartered in Chula Vista, serves as the primary secondary school district.[140] The Chula Vista Elementary School District, the largest K-6 district in the State of California, with 44 campuses, serves publicly educated kindergarten through sixth grade students.[141]

Chula Vista is home to one of the four private colleges in San Diego County and is host to Southwestern College, a community college founded in 1961 that serves approximately 19,000 students annually.

The city has been trying since 1986 to get a university located in the city.[142] In 2012, the city acquired a 375-acre (152 ha) parcel of land in the Otay Lakes area intended for the development of a University Park and Research Center, and chose a master developer for the project;[143] who later backed out of the project.[144] State Assemblymember Shirley Weber has proposed that the state open a satellite or extension campus of the California State University system at the site, with the hope that it will grow into a full university.[145]

Media

Chula Vista is served by The Star-News and The San Diego Union-Tribune.

Transportation

Major freeways and highways

Chula Vista is served by multiple Interstates and California State Routes. Interstate 5 begins to the south of the city and runs through its western edge. Interstate 5 connects Chula Vista to North County and beyond to Greater Los Angeles and Northern California. Interstate 805 serves as a bypass to Interstate 5, linking to the latter interstate in Sorrento Valley. Interstate 905 runs from the Otay Mesa Port of Entry and is one of three auxiliary three-digit Interstates to meet an international border. State Route 54 and State Route 125 serve as highways to East County cities via northern and northeastern corridors.

Notable people

Sister cities

Chula Vista has three sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:[146]

| City | Province/State/Prefecture | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Cebu City | ||

| Irapuato | ||

| Odawara |

Notes

- The Spanish translation for Chula Vista can be translated several ways. Chula can be translated as "cute",[13] or "pretty".[14]

- District 1 contains: Bonita Long Canyon, Eastlake, Rancho Del Rey, and Rolling Hills Ranch.

- District 2 contains: Northwest Chula Vista (Bayfront, Central, and Hilltop) and Terra Nova.

- District 3 contains: Greg Rogers, Otay Ranch, Rancho Del Rey, Sunbow.

- District 4 contains: Southwest Chula Vista (Castlepark, Harborside, and Otay.

References

- "Heritage Museum". Public Library Chula Vista. City of Chula Vista. 2012. Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

"Happening Sunday, August 12th". Third Avenue Village. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

San Diego Magazine 2011, p. 134, Carpenter 1992, p. 31 - Bianca Bruno (October 6, 2010). "Growing up in "Chula-juana"". The Vista. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

Anne-Marie O'Connor (September 11, 2002). "Cross-Border Lifestyle Requires Patience". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

Tom Greeley (April 15, 1985). "S.D. County's Cities Defy The Negatives, Accent The Positives". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 27, 2011. - "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "Mayor and Council". City of Chula Vista. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- "City Manager's Home Page". City of Chula Vista. Archived from the original on November 20, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Chula Vista". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- Karen Kucher (March 8, 2011). "The faces of San Diego's changing demographics". U-T San Diego. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- "Chula Vista (city), California". Quick Facts. United States Census Bureau. April 22, 2015. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

Population, 2010 243,916

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "About Chula Vista". City of Chula Vista. 2012. Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

Chula Vista means "beautiful view" and there is more to see and do here than you can imagine!

"Grow Lemons for Pleasure and Profit". Rural Californian. Rural Californian. 1893. p. 490.The San Diego Land and Town Company own 5,000 acres of beautiful mesa land adjoining the thriving town of National City, and named it Chula Vista (most exquisitely beautiful view) with a gentle rising slope from the Bay of San Diego to the east.

Bowler, Edward; Bowler, Barbara (October 2002). Cruising Guide to San Diego Bay. Paradise Cay Publications. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-939837-55-7. - "Chula Vista in Perspective, Chapter 3" (PDF). Chula Vista General Plan. City of Chula Vista. December 13, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- Roseman, Frank M.; Watry Jr., Peter J. (April 21, 2008). Chula Vista. Arcadia Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4396-2011-3.

Hadleigh, Boze (November 1, 2007). Mexico's Most Wanted™: The Top 10 Book of Chicano Culture, Latin Lovers, and Hispanic Pride. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-59797-149-2. - Leland Fetzer (2005). San Diego County Place Names, A to Z. Sunbelt Publications, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-932653-73-4.

Darlow, Alfred; Brook, Harry Ellington (1903). The Rand-McNally Guide to California Via the Overland Route. Rand, McNally. p. 152. - Lister, Priscilla (October 13, 2014). "Bayfront walk in Chula vista has wildlife, public art". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

"Living Coast Discovery Center". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Department of the Interior. March 6, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2014. - "Prehistoric South Bay". SunnyCV. South Bay Historical Society. 2014. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- Harper, Hilliard (June 28, 1987). "Finding Fossils in San Diego Area Easy as Kicking Rocks". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- Schoenherr, Steve; Orgovan, Harry, eds. (December 2017). "First People". South Bay Historical Society Bulletin (17). Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "Brief History of Chula Vista". City of Chula Vista. City of Cula Vista. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- Schulte, Author Richard (June 2, 2019). "Exhibit shows Kumeyaay history in the South Bay". Cool San Diego Sights!. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Carrico, Richard. "Kumeyaay History". www.kumeyaay.com. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Schoenherr, Steven (October 29, 2004). "Otay Valley". San Diego Local History. University of San Diego. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Schoenherr, Steven (February 4, 2015). "SBHS News . . ". SunnyCV.com. South Bay Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Hamersly 1883, pp. 136–140, Price 1883, p. 445

- Coast 2 Coast Environmental, Inc. (November 5, 2010). Phase I Environmental Site Assessment (PDF) (Report). County of San Diego. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

Schoenherr, Steven (October 29, 2004). "Otay Valley". Schoenherr Home Page. South Bay Historical Society. Retrieved March 4, 2020. - Nancy Ray (May 26, 1986). "Chula Vista, County's 2nd Largest City, Has Problem With Image". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Walter, Susan (November 26, 2011). "South Bay's juicy history". Star News. Chula Vista, California. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

The Great Southwest 1889, p. 4 - Davis et al. 2012.

- "Historic Homes". About Chula Vista. City of Chula Vista. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

Frank M. Roseman; Peter J. Watry (2010). Chula Vista. Arcadia Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7385-8016-6.

Schoenherr, Steve (July 29, 2012). "Jewish History in Chula Vista" (PDF). Jewish American Society for Historical Preservation. Retrieved February 28, 2019. - Davis et al. 2012, p. 17.

- Schoenherr, Steve (August 2017). "Middle Broadway". South Bay Historical Society Bulletin (16). Retrieved February 28, 2019.

"Railroads of the South Bay". South Bay Historical Society Bulletin (4). July 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

William Ellsworth Smythe (1907). History of San Diego, 1542–1907: An Account of the Rise and Progress of the Pioneer Settlement on the Pacific Coast of the United States ... History Company. p. 439. - Davis et al. 2012, p. 18.

- Sampite-Montecalvo, Allison (April 12, 2017). "Greg Rogers historic home in Chula Vista up for sale". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

Roseman & Watry 2008, p. 38 - Davis et al. 2012, p. 23, Jones 2001, p. 92

- Davis et al. 2012, p. 23.

- Guevarra 2012, pp. 45–46

- Tjoa, May (March 27, 2016). "Exhibit at Chula Vista Heritage Museum Marks Centennial of Historic Flooding". KNSD. San Diego. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- Perry, Tony (May 25, 2015). "With San Diego again drought-ridden, 1915 'Rainmaker' saga is revisited". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- Davis et al. 2012, p. 25

"Chula Vista, California Golf Course". Southerby's International Realty. Sotheby's International Realty Affiliates LLC. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

McGrew 1922, p. 32 - Davis et al. 2012, p. 27

Schoenherr, Steve (November 24, 2014). "Gunpower Point History". Sunnycv.com. South Bay Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2018. - Davis et al. 2012, pp. 28–29, Scharf 1978, Gustafsson 2011, Niiya 1993, p. 40

- Guevarra 2012, p. 92, Patacsil, Guevarra & Tuyay 2010, p. 22

- Davis et al. 2012, p. 28, Moyer 1969, p. 10

- Davis et al. 2012, p. 29.

- Saito 2009, p. 46

- Dean, Ada; Golden, Donna; Roseman, Frank; Watry, Peter. "Rohr Aircraft Corporation". City of Chula Vista Heritage Museum. City of Chula Vista. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Davis et al. 2012, p. 42, Showley 1999, p. 252

- Luzzaro, Susan (December 6, 2015). "Vogue Theater for sale — not to be destroyed". San Diego Reader. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

Roseman & Watry 2008, p. 90 - Davis et al. 2012, p. 43

Rowe, Peter (May 19, 2012). "WWII: Internments for San Diego's Japanese-Americans". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

Moss, James E.; Schlenker, Gerald (Winter 1972). "The Internmetn of the Japanese of San Diego County During the Second World War". The Journal of San Diego History. 18 (1). Retrieved May 2, 2018. - "From the Archives April 8, 1942: San Diegans leave for internment camps". San Diego Union-Tribune. April 8, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- Sano, Joseph K. (2012). "Joseph K. Sano papers: 1923-1951 (bulk 1941-1951)". Bentley Historical Library. University of Michigan. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

"Oakland University to share survivors' stories of racial discrimination during World War II". Oakland University. November 1, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2018. - Soto, Onell R. (September 21, 2008). "Equal-rights gains have local roots". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

Five Views. State of California--the Resources Agency, Department of Parks and Recreation, Office of Historic Preservation. 1988. pp. 194–195.

Niiya 1993, p. 280 - Davis et al. 2012, pp. 45-46.

- Blocker, John. "San Diego's Lost Landscape: La Punta" (PDF). Otay Valley Regional Park. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

Schoenherr, Steve (December 12, 2014). "La Punta". Sunnycv. South Bay Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

Taylor 2016, p. 37 - Davis et al. 2012, p. 46

Sherman, Pat (June 27, 2010). "Driven to preserve drive-in memories". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved May 3, 2018. - Sanford, Jay Allen (August 1, 2008). "Drive-In Theaters in San Diego: Complete Illustrated History 1947 thru 2008 (45 new pics added 7-4-09!)". San Diego Reader. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

THE BIG SKY Drive-In opened in June 1955 at 2245 Main Street in Chula Vista. With 21 acres of space, its car capacity of 2000 made it one of the four largest ozones in the U.S. (Los Aitos in Long Beach held 2100 while the 41 Twin in Franklin, Wisconsin, and the Twin Open Air in Oak Lawn, Illinois, were the same size as the Big Sky.)

Sanford, Jay Allen (July 6, 2006). "Field of Screens". San Diego Reader. p. 5. Retrieved May 3, 2018. - Schoenherr & Oswell 2009, p. 109

"Annexations in the Valley". Sweetwater Valley Civic Association. 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

Valdez, Jonah (March 1, 2017). "Our little hills, forever near". San Diego Reader. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

Coleman, Eugene Victor (1973). The Urbanization of the Sweetwater Valley, San Diego County (PDF) (Masters Thesis). San Diego State University. Retrieved March 1, 2019. - Guevarra 2012, pp. 47

- Zhao & Park 2013, p. 1042

- Historic Resources Assessment of 2711, 2725, and 2729 Granger Avenue, National City, San Diego County, California (PDF). BRG Consulting, Inc. (Report). County of San Diego. August 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- Katherine Poythress (January 30, 2013). "Imploding a bayfront fixture: If weather conditions cooperate, the now-defunct South Bay Power Plant in Chula Vista will be demolished on Saturday morning". San Diego Union. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- "Chula Vista celebrates its first 100 years". San Diego Union-Tribune. October 12, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- Keith A. Owens (January 3, 1986). "Montgomery Merging With City : Chula Vista Annexation Is Cause to Celebrate". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Ray, Nancy (September 8, 1986). "Planners' Advice Ignored : S.D.-Chula Vista Land Giveaway Is Questioned". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Dykens, Margaret; Gillette, Lynett; Melli, Jim; Gohier, Francois. "Walrus". San Diego Natural History Museum. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

Berta 2017, p. 230 - Mallgren, Laura (June 2, 2000). "Park to be re-named in honor of late mayor". The Star-News. Chula Vista. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

Reza, H.G. (January 19, 1991). "Chula Vista Mayor Dies; Held Office for One Month : Illness: Yearlong battle with cancer ends in death for 36-year-old Gayle McCandliss". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 3, 2018. - Patrice Milkovich (August 8, 2004). "Chula Vista – where the world's best train". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- "Chula Vista". Olympic Training Centers/Sites & Tours. United States Olympic Committee. 2013. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- "Data Series 233". U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Department of the Interior. March 8, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Lake, Heather (October 2, 2015). "Sweetwater desalination plant undergoes expansion". KSWB. San Diego. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Pentney, Sandra; DeGiovine, Michael M. (November 20, 2015). "A Historical Survey Report for Bonita Pump Station Project, San Diego, California" (PDF). City of San Diego. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Los Angeles District, Corps of Engineers. "Camp Otay". California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. Archived from the original on February 6, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

Schoenherr, Steve (March 28, 2015). "Military Bases in the South Bay". SunnyCV. South Bay Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2015. - Bevil, Alexander D. (February 28, 2014). "Cuyamaca Racho State Park Historic Background Study & Historic Inventory" (PDF). Department of Parks and Recreation. State of California. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

24 May 2015

- "Spotlight" (PDF). Office of the City Manager. City of Chula Vista. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Weisberg, Lori (July 10, 2003). "Chula Vista No. 7 in the nation in galloping growth". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- "Horses Stampede Through Chula Vista Streets". KGTV. March 24, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Donohue, Andrew (May 8, 2006). "Chula Vista Looking to Chargers". Voice of San Diego. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

"Chula Vista shows Chargers execs potential stadium site". ESPN. Associated Press. July 27, 2006. Retrieved May 3, 2018. - "Chula Vista Out As Possible Chargers Stadium Site". 10News.com. Internet Broadcasting Systems, Inc. June 24, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- Taylor 2016, p. 67

Weisberg, Lori; Berestein, Leslie (May 14, 2009). "County not go-to spot for Latinos in region". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved May 3, 2018.The newcomers tend to gravitate toward North County, he said, and the transplants near the border in the Chula Vista area.

Marosi, Richard (June 7, 2008). "U.S. a haven for Tijuana elite". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 3, 2018.So many upper-class Mexican families live in the Eastlake neighborhood and Bonita, an unincorporated community adjacent to Chula Vista, that residents say the area is becoming a gilded colony of Mexicans, where speaking English is optional and people can breathe easy cruising around in their Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs.

"Wealthy Mexicans Flee Tijuana for U.S. to Escape Kidnappings". Fox News. Associated Press. January 9, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2018. - Moore, Solomon (December 8, 2009). "How U.S. Became Stage for Mexican Drug Feud". New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

Epstein, David; ProPublica (February 2016). "How DEA Agents Took Down Mexico's Most Vicious Drug Cartel". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

"Drug smuggling tunnels with rail systems discovered under US border with Mexico". The Daily Telegraph. United Kingdom. Associated Press. April 5, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

Marosi, Richard (August 14, 2009). "17 charged in string of brutal kidnappings and slayings in San Diego suburbs". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 11, 2020. - Zumbrun, Joshua. "America's Most Boring Cities". Forbes. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- Luzzaro, Susan (September 30, 2013). "Chula Vista from boom to bust to boom". San Diego Reader. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

Kotkin, Joel (June 18, 2013). "America's Fastest-Growing Cities Since The Recession". Forbes. New York City. Retrieved March 7, 2017. - Bruno, Bianca (June 2, 2014). "Don't Call Us 'Chulajuana': Chula Vistans' 3 Big Frustrations". Voice of San Diego. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

"Survey shows mix of awareness and perceptions about Chula Vista". News. City of Chula Vista. April 18, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2017. - Cana, Eliza (December 3, 2015). "Chula Vista Scholar to the Philippines". The Sun. Southwestern College. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

Chula Vista has quietly become the Philippines 2.0. With nearly 31,244 Pinoy living in the city, according to the American Community Survey in the Census.

- Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Los Angeles; Union of Pan Asian Communities; M. Jamie Watson; Sam Chen; SunDried Penguin (2015). A Community of Contrasts (PDF) (Report). Union of Pan Asian Communities. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- Stimson, Brie; Galindo, Ramon (February 25, 2017). "Chula Vista Training Center Celebrates Ownership Change". KNSD. San Diego. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

Alvarez, Elizabeth (January 24, 2017). "Athletic Training Center in Chula Vista expands under new ownership". KUSI. San Diego. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017. - "Chula Vista Post Office Dedicated To Fallen SDPD Officer". KPBS. San Diego. City News Service. March 6, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- Rie, Takumi (August 2, 2016). "Fil-Am cop killed in line of duty honored by community". GMA News. Philippines. KBK. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- "Gunned-Down San Diego Officer Was a 16-Yr Vet; 2nd Suspect Arrested". Fox News. New York City. July 29, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

Peterson, Karla (July 30, 2016). "Slain San Diego police officer remembered as the kind 'every chief would want to have'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2017. - Sampite-Montecalvo, Alison (November 14, 2016). "Homelessness count up in Chula Vista". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Luzzaro, Susan. "Chula Vista addresses homeless crisis". San Diego Reader. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Halverstadt, Lisa (May 2, 2017). "Chula Vista Sees Homelessness Drop Following Measure Targeting Large Vehicles". Voice of San Diego. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Plante, Dan (September 25, 2018). "Chula Vista has homeless shelter crisis; State of California to send millions of dollars". KUSI. San Diego. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- Solis, Gustavo (August 15, 2018). "Chula Vista aims to build South Bay version of Central Park". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- "City of Chula Vista Drainage Basins" (PDF). Geographic Information System. City of Chula Vista. June 20, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

Roca & Lipski 1999, p. 51 - Department of Conservation (2010). "Fault Activity Map of California (2010)" (Map). Fault Activity Map of California. State of California. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

Arnold Ross; Robert J. Dowlen (1973). Studies on the Geology and Geologic Hazards of the Greater San Diego Area, California: A Guidebook Prepared for the May 1973 Field Trip of the San Diego Association of Geologists and the Association of Engineering Geologists. San Diego Geological Soc. pp. 77–81. - Artim, Ernst R.; Pinckney, Charles J. (March 1973). "La Nacion Fault System, San Diego, California". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 84 (3): 1075–1080. Bibcode:1973GSAB...84.1075A. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1973)84<1075:LNFSSD>2.0.CO;2.

Artim, E. R.; Streiff, D. (1981). Trenching the Rose Canyon Fault Zone San Diego, California (PDF) (Report). United States Geographical Survey. - Roquemore 1997, pp. 31–32

- Bailey, Torrey (May 3, 2017). "Neighborhood Watch: Chula Vista". San Diego City Beat. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "Sweetwater Marsh". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. United States Department of the Interior. July 9, 2010. Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- "Open Space". Public Works Operations. City of Chula Vista. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Luzzaro, Susan (September 19, 2012). "Chula Vista West Side's No-Mello Divide". San Diego Reader. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Rancho Del Rey". Open Space. City of Chula Vista. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Reed, Candice (November 25, 2006). "Otay Ranch's victory Lap". San Diego Daily Transcript. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Marosi, Richard (June 7, 2008). "U.S. a haven for Tijuana elite". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- "New Rapid Transit Connects South Bay to Downtown, Free Week of Rides". KNSD. San Diego. August 28, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- "Mediterranean Climate". County Television Network. County of San Diego. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Chula Vista (city), California". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. July 8, 2009. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- "Detailed Tables". 1990 Census of Population and Housing. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- "Number of Inhabitants, California" (PDF). 1980 Census of Population. U.S. Bureau of the Census. March 1982. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- Katz & Lang 2004, p. 106

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Chula Vista city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000". Census 2000. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- "General Social and Economic Characteristics" (PDF). 1980 Census of Population. U.S. Bureau of the Census. July 1983. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- "City of Chula Vista: Small Business". City of Chula Vista. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- "Shopping in Chula Vista". City of Chula Vista. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- "Golf Courses in Chula Vista". City of Chula Vista. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- "Chula Vista Attractions". City of Chula Vista. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- "City of Chula Vista, California Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ended June 30, 2019". Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- "Nature Center". Community Services. City of Chula Vista. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- "Chula Vista Launch Ramp". SD Boating.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- "Third Avenue Village". Third Avenue Village Association. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- Lothspeich, Dustin (November 2, 2018). "Mattress Firm Amphitheatre Gets New Name". KNSD. San Diego. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- "OnStage Playhouse Launches Community Conversation About Gun Violence". Broadway World. May 7, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

"Meet Teri Brown of OnStage Playhouse in Chula Vista". SD Voyager. Voyage Group of Magazines. January 25, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2019. - "Chula Vista Olympic Training Ctr". United States Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on January 31, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- "Chula Vista FC Aiming to Continue Upstart Beginning to 2015 USOC". ussoccer.com. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- "Functions and Duties". City of Chula Vista. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "Elections". City of Chula Vista. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- City of Chula Vista CAFR Archived May 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved August 7, 2009

- Solis, Gustavo (May 9, 2019). "Chula Vista firefighters may stop responding to low-priority 911 calls". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- Ken Stone; Hoa Quách; Steven Bartholow (July 29, 2011). "State GOP Chairman Slams Remap Plan as Favoring Democrats". LaMesa-MountHelix Patch. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- "SWDB Web GIS". Statewide Database, Berkeley Law School. University of California, Berkeley. 2011. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- "Senators". California State Senate.

- "Members". California State Assembly.

- "California's 53rd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- "Report of Registration - State Reporting Districts" (PDF). Registrar of Voters. County of San Diego. January 14, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- Jason Alderman; Gitanjali Gurudatt Borkar; Amanda Garrett; Lindsay Hogan; Janet Kim; Winston Le; Veronica Louie; Alissa Marque; Phil Reiff; Colin Christopher Richard; Peter Thai; Tania Wang; Craig Wickersham. "The Most Conservative and Liberal Cities in the United States" (PDF). The Bay Area Center for Voting Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- "Sweetwater Union High School District". SUHSD. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- "Community" (PDF). 2011 Membership & Resource Guide. Chula Vista Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

Located between the City of San Diego and United States/Mexico International Border, the Chula Vista Elementary School District is the largest K-6 district in the state

- Srikrishnan, Maya (October 27, 2015). "Chula Vista Is a College Town in Search of a College". Voice of San Diego. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

South Bay residents longed for a four-year school of their own at least as far back as 1986.

- Harvey, Katherine P. (December 17, 2012). "Chula Vista picks developer for university master plan". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- Moreno, Robert (November 7, 2015). "HomeFed backs out of university development". The Star News. Chula Vista. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- Bowler, Matthew (August 4, 2014). "Assemblywoman Shirley Weber Wants To Make Chula Vista University A Reality". KPBS. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- "SCI: Sister City Directory". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

Further reading

- Berta, Annalisa (2017). The Rise of Marine Mammals: 50 Million Years of Evolution. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421423265.

- Carpenter, Allan (1992). Facts about the cities. H.W. Wilson. ISBN 9780824208004.

- Davis, Shannon; Stringer-Bowsher, Sarah; Krintz, Jennifer; Ghabhláin, Sinéad Ní (November 2012). Historical Resources Survey, Chula Vista, California (Report). ASM Affiliates, Inc. City of Chula Vista.

- Guevarra, Rudy P., Jr (2012). Becoming Mexipino: Multiethnic Identities and Communities in San Diego. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813553269.

- Gustafsson, Jeri Gulbransen (2011). Golden, Donna (ed.). "They made Chula Vista History!: Saburo Muraoka". Altrusa Club of Chula Vista Inc. Foundation. City of Chula Vista.

- Hamersly, Lewis Randolph (1883). Records of Living Officers of the United States Army. Hamersly.

- Jones, Gregory O. (2001). The American Sailboat. MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 9780760310021.

- Katz, Bruce; Lang, Robert E., eds. (2004). Redefining Urban and Suburban America: Evidence from Census 2000. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0815748588.

- McGrew, Clarence Alan (1922). City of San Diego and San Diego County: The Birthplace of California. American Historical Society.

- Moyer, Cecil C. (1969). Historic Ranchos of San Diego. Union-Tribune Publishing Company. ISBN 9780913938089.

- Niiya, Brian (1993). Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present. VNR AG. ISBN 9780816026807.

- Patacsil, Judy; Guevarra, Rudy, Jr; Tuyay, Felix (2010). Filipinos in San Diego. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738580012.

- Price, George Frederic (1883). Across the Continent with the Fifth Cavalry. D. Van Nostrand.

- Roca, Ana; Lipski, John M., eds. (1999). Spanish in the United States: Linguistic Contact and Diversity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110165722.

- Roquemore, Glenn, ed. (1997). The Seismic Risk in the San Diego Region: Special Focus on the Rose Canyon Fault Systems: Workshop Proceedings. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9780788142628.

- Roseman, Frank M.; Watry, Peter J. (2008). Chula Vista. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738556161.

- Saito, Leland T. (2009). The Politics of Exclusion: The Failure of Race-neutral Policies in Urban America. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804759298.

- Schoenherr, Steven; Oswell, Mary E. (2009). Bonita. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738570006.

- Schoenherr, Steve (March 11, 2010). "Chula Vista Centennial History Bibliography". University of San Diego. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- Showley, Roger M. (1999). San Diego: Perfecting Paradise. Heritage Media Corporation. ISBN 9781886483248.

- Taylor, Kimball (2016). The Coyote's Bicycle: The Untold Story of 7,000 Bicycles and the Rise of a Borderland Empire. Tin House Books. ISBN 9781941040218.

- Scharf, Thomas L. (1978). "Before the War: The Japanese In San Diego". San Diego Historical Society Quarterly. 24 (4).

- Zhao, Xiaojian; Park, Edward J. W., eds. (2013). Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842401.

- "Agenda", San Diego Magazine, 63 (5–8), 2011, ISSN 0036-4045, retrieved March 29, 2013

- The Great Southwest: A Monthly Journal of Horticulture. 1889.