Coleville, Saskatchewan

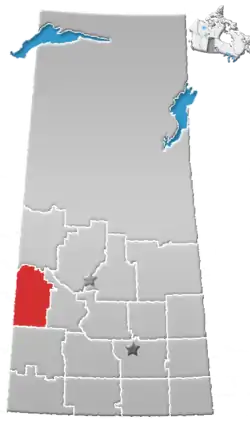

Coleville (2016 population: 305) is a village in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan within the Rural Municipality of Oakdale No. 320 and Census Division No. 13. The village's main economic factors are oil and farming, namesake of the Coleville oilfields. The village is named for Malcolm Cole who became the community's first postmaster in 1908.

Coleville | |

|---|---|

| Village of Coleville | |

Coleville  Coleville | |

| Coordinates: 51°42′38″N 109°15′25″W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Region | Western |

| Census division | 13 |

| Rural Municipality | Oakdale No. 320 |

| Post office Founded | 1907 |

| Incorporated (Village) | 1953-07-01 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal |

| • Governing body | Coleville Village Council |

| • Mayor | Harold Lea |

| • Administrator | Gillain Lund |

| • MLA | Ken Francis |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.87 km2 (0.72 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 305 |

| • Density | 162.8/km2 (422/sq mi) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (CST) |

| Highways | |

| Website | Village of Coleville |

| [1][2][3][4] | |

History

- Early settlers

In 1905, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway Company surveyed the area in preparation for a railway line, and the prospect of rail service attracted settlers to the area. The first settlers arrived in 1906, most of whom had shipped their effects to Battleford, the site of the Dominion Lands office in the area. With the nearest source of wood being on the banks of the South Saskatchewan River, approximately 110 kilometres (68 mi) away, most of the first homes constructed in the area were sod houses, either frame structures covered with sods, or else built entirely out of sods. These structures generally collapsed after a few years, however one sod house built by English immigrant James Addison, between 1909 and 1911, has been occupied continuously from its construction to the present.

The site for the Hamlet of Coleville was purchased from Charles Farris, and built on his purchased homestead NE 6-32-23-W3. In 1913, Charles Cole submitted names to the railway, and Coleville was chosen for the station and townsite.

Coleville incorporated as a village on July 1, 1953.[5]

- Railway

The grade was built for the Biggar–Loverna line of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in 1912, and steel was laid in 1913. The construction of the rail site in Coleville began in 1913 with the construction of the railway station and coal box. Jack Binks, section foreman, was the station's first occupant, and George Barrett was the first station agent. After the construction of the station, a water well was required for the steam engines. In 1914 a two-pen, four-car stock yard and hog chute were built, and an 18 metre (60 foot) well was dug by hand. A pump house was built, and the Coleville water tower, which is still in use today, was erected. The first pumpman was Mike Crown. The Bigger–Loverna line became part of the Canadian National Railway in 1923. The section toolhouse was built in 1926, and in 1953 a two-car loading platform was built, and an electric pump was installed in the pumphouse.

The station was closed in 1979, and the tracks were torn up in 1998.

- Elevators

Soon after the arrival of the railroad in 1913, a grain elevator was built by the Scottish Co-op. Bill Donald was its first agent. This original elevator was replaced in 1940 by a new elevator with a storage capacity of 45,000 imperial bushels (1,600 m3). The Alberta Pacific elevator was built in 1917, with Joe Barrows as its first agent. The elevator had a capacity of 23,000 imperial bushels (840 m3). It was bought out by Federal Grain in 1943.

The Saskatchewan Wheat Pool was formed in 1924, and built an elevator in Coleville in 1925, now called Pool A. Alf Beal was the first operator. Pool A had a storage capacity of 30,000 imperial bushels (1,100 m3). In the late 1970s Pool A was sold and torn down. The Scottish Co-op elevator was purchased in 1948 by the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool and became Pool B. The Federal Grain elevator was acquired by the Pool in 1972, and became Pool C. Pool C was torn down in 1998.

- Coleville Post Office

One of the first settlers was Malcolm Cole, who came with his father in 1906, and set up a post office and general store on his homestead shortly thereafter, in the summer of 1907. He named the post office Coleville, derived from his own last name, and the suffix -ville. His brother, Charles Cole, who arrived in 1907, was the postmaster from 1908 until 1917. Around 1914 the post office was moved from the Cole homestead to the townsite of Coleville. When John Brent turned the post office over to H. L. Dumouchel, the post office was moved to the Dumouchel store.

Before railway service to the area, mail was carried in from Battleford. After the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was built, the mail was carried from Scott by R. A. Cummings of Kerrobert.

Cork obliterators (used to cancel stamps) in the second half of the 20th century are comparatively rare; however, cork obliterators created by H.L. Dumouchel (acting postmaster from 1928 until 1950) were still in use until they were lost in a post office remodelling sometime after 1951.

- Coleville Rural Telephone Co.

The Coleville Rural Telephone Co. came into being on Friday, January 28, 1916, following a meeting of a group of ratepayers in Dumouchel's Drug Store. Shortly thereafter a charter was granted by the Department of Telephones and the company was started by issuing a debenture. On February 5, 1917, a tender of $11,298.40 by Heise, O'Bready and Small of Elstow was accepted for the construction of the system. The switchboard was located in the store of A. G. Bridger, who was also publisher of the district news sheet. Bridger resigned in 1919, and George Manning became secretary-treasurer and operator. His salary was $40 a month plus long distance commissions. In 1921 this increased to $60 a month. The linesman was Ed Hogarth, who was paid 50¢ an hour plus 10¢ for mileage.

Subscribers paid an annual rental, which covered switching fees and operator costs. Landowners paid a tax levy on phone lines running through their property, which covered repairing and building lines. The levy was based on the quarters of land through which telephone lines ran. There were two rates. A quarter of land which had a line passing through it paid a 'straight' rate, and a quarter of land in which someone lived and had a phone paid a higher 'take-off' rate. Since the 'straight' rate levy was charged regardless of whether the owner had phone service, land owners without phones could be paying as much or more as land owners with phone service. In spite of attempts to reform this system, it remained in place until the government took over the service. In addition to the annual rental and line levy, there was a special levy to pay back the debenture.

Financing for the company was always difficult, as the large rural population meant the construction and maintenance of many miles of poles and wire for each rural subscriber. In the early years, subscribers who could not pay rentals had their phone removed at their expense; however, by the time of the depression in the 1930s, this was no longer practical or desirable. Instead, subscribers were able to pay off their debt by assisting in the erection of new lines and the maintenance of old ones. Because of the difficulties associated with providing rural telephone service, it was resolved by the Rural Telephone Company as early as 1930 that they ask the provincial government to take over telephone operation for the entire province. While the government did finally take over telephone service, this did not occur until the late 1970s.

Early on, use of the phones and the company's equipment was strictly regulated. There was a three-minute time limit for conversations. Those who did not have a phone were asked to pay 75¢ for using their neighbour's. Farmers and housewives faced fines or prosecution for the use of telephone poles as hitching posts, or incorporating them into their barbed wire fences or clotheslines.

In 1935 George Manning died, and his wife carried on in his capacity until October 1, 1937, when Pat O'Bready, along with his wife Irene, took over as operator, linesman, and troubleman. They were paid $800 per year plus commissions, though this salary was on paper only. In 1940 the company began to emerge from the depression and gain solid financial footing, and in February 1942 the debenture debt was retired.

In 1950, a wind storm on April 15 damaged or destroyed nearly the entire telephone system, which took six months to repair.

In March 1954, Saskatchewan Government Telephones bought the Coleville Telephone plant for $2,301 while the Rural Company remained agent for the town. A new switchboard was installed, and private lines were made available. In 1956 black wall or desk cradle phones arrived, and the old box-crank phones were reclaimed. On July 1, 1957, Pat O'Bready resigned as linesman and operator, although he retained the post of troubleman. Six months later the Rural Company resigned as agent for the Government Telephones.

By the 1960s, 24-hour service was being provided. Previously official hours had been from 8 a.m. until 9 or 10 p.m. (depending on season) on weekdays and Saturday, and from 10 a.m. until 2 p.m. on Sundays, although there was always someone available for emergencies. In 1965 the automatic dial system was completed, and calls were no longer routed through the operator. In 1967 the Coleville Rural Teleqhone Co. Ltd. was sold to the Kindersley Rural Telephone Co. Ltd. for $1, and Coleville was allowed one member to sit on the Kindersley board. In 1977 the government took over the Kindersley Rural Telephone Co.

Demographics

In the 2016 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the Village of Coleville recorded a population of 305 living in 137 of its 163 total private dwellings, a -2% change from its 2011 population of 311. With a land area of 1.87 km2 (0.72 sq mi), it had a population density of 163.1/km2 (422.4/sq mi) in 2016.[8]

In the 2011 Census of Population, the Village of Coleville recorded a population of 311, a 25.4% change from its 2006 population of 248. With a land area of 1.27 km2 (0.49 sq mi), it had a population density of 244.9/km2 (634.2/sq mi) in 2011.[9]

Attractions

Amenities in the community include a library, a skating rink and a two-sheet curling rink. At nearby Laing's Park, also referred to as the three-mile park in reference to its distance from village, are several ball diamonds and a nine-hole golf course. The golf course once featured a pumpjack hazard.

Education

Coleville is located within the Sun West School Division. Children attend the Rossville School located within the community for kindergarten through grade 7. For grades 8–12, students are bused to Kindersley Composite School, located approximately twenty minutes away in Kindersley.

The Warwick School was a one-room schoolhouse for the area that was closed in 1940. It was moved to Main Street in Coleville in 1946 where it served as the RM's office. When the RM moved to a new building in the 1980s, it continued to serve the community, first as the local Scout and Brownie hall, and now as a playschool.

Notable people

Jeni Mayer, author of such children's books as The Mystery of the Turtle Lake Monster and Suspicion Island, was born and raised in Coleville. Canadian artist, Jean A. Humphrey lived in Coleville for over 50 years.

References

- National Archives, Archivia Net, Post Offices and Postmasters, archived from the original on 2006-10-06

- Government of Saskatchewan, MRD Home, Municipal Directory System, archived from the original on November 21, 2008

- Canadian Textiles Institute. (2005), CTI Determine your provincial constituency, archived from the original on 2007-09-11

- Commissioner of Canada Elections, Chief Electoral Officer of Canada (2005), Elections Canada On-line, archived from the original on 2007-04-21

- "Urban Municipality Incorporations". Saskatchewan Ministry of Government Relations. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "Saskatchewan Census Population" (PDF). Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Saskatchewan Census Population". Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Saskatchewan)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses (Saskatchewan)". Statistics Canada. June 3, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2020.