History of Nagorno-Karabakh

Nagorno-Karabakh is located in the southern part of the Lesser Caucasus range, at the eastern edge of the Armenian Highlands, encompassing the highland part of the wider geographical region known as Karabakh.[1] Under Russian and Soviet rule, the region came to be known as Nagorno-Karabakh, meaning "Mountainous Karabakh" in Russian. The name Karabakh itself (derived from Persian and Turkic, and meaning "Black Vineyard") was first encountered in Georgian and Persian sources from the 13th and 14th centuries to refer lowlands between Kura and Aras rivers and adjacent mountainous territory.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Artsakh |

|

| Antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

| Early Modern Age |

| Modern Age |

Following the collapse of Soviet Union, most of this area came under the control of the de facto Artsakh Republic, which had economic, political, and military support from Armenia but has been internationally recognized as the de jure part of Azerbaijan. As a result of the 2020 war, all surrounding territories and some areas within Nagorno-Karabakh were retrieved by Azerbaijan, yet the final status of the region is still a subject of negotiations between Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. This article encompasses the history of the region from the ancient to the modern period.

Ancient history

The region of Nagorno-Karabakh was occupied by the people known to modern archaeologists as the Kura-Araxes, and is located between the two rivers bearing those names. Little is known about the ancient history of the region, primarily because of the scarcity of historical sources. Jewelry has been found within the present confines of Nagorno-Karabakh inscribed with the cuneiform name of Adad-Nirari, King of Assyria (c. 800 BCE).

The first mention of the territory of modern Nagorno Karabakh is in the inscriptions of Sardur II, King of Urartu (763–734 BC), found in the village of Tsovk in Armenia, where the region is referred to as Urtekhini. There are no additional documents until the Roman epoch.

By the beginning of the Hellenistic period the population of Nagorno-Karabakh was neither Armenian nor even Indo-European and it was Armenized only in the aftermath of Armenian conquest.[2] Robert Hewsen does not exclude the possibility of the Armenian Orontid dynasty exercising control over Nagorno-Karabakh in the 4th century BC, however, it is disputed by many other scholars, who limit Orontid Armenia with Sevan lake.[3][4][5]

Similarly, Robert Hewsen in the earlier work[6] and Soviet historiography[7][8] date inclusion of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia to the 2nd century BC.

Legend of Aran

According to the local traditions held by many people in the area, the two river valleys in Nagorno-Karabakh were among the first to be settled by Noah's descendants.[9] According to a 5th-century CE Armenian tradition, a local chieftain named Aran (Առան) was appointed by the Parthian King Vologases I (Vagharsh I) to be the first governor of this province. Ancient Armenian authors, Movses Khorenatsi and Movses Kaghankatvatsi, name of it Aran the ancestor inhabitants of Artsakh and next province Utik, the descendant of Sisak (the ancestor and eponym next province Sisakan, differently Siunik),[10][11] and through it—the descendant of Haik, the ancestor and eponym of all Armenians.[12][13]

Artsakh as province of the Kingdom of Armenia

Strabo characterizes "Orchistenê" (Artsakh) as "the area of Armenia exposing the greatest number of horsemen".[14] It is unclear when Orchistenê became part of Armenia. Strabo, carefully listing all gains of Armenian kings since 189 BC, does not mention Orchistenê, which indirectly shows that it probably has been transferred to the Armenian empire from the Persian satrapy of "East Armenia". There are ruins of the city of Tigranakert near the modern city of Agdam. It is one of four cities with this name that were built in the beginning of 1 BC by the king of Armenia, Tigranes the Great. Recently Armenian archaeologists have conducted excavation at the site of this city. Fragments of a fortress, and also hundreds of artifacts similar to those found in excavations of ancient sites in Armenia proper, have been unearthed. The outlines of a citadel and a basilica dated to the 5th–6th centuries AD have been revealed. Excavation have shown that the city existed since the 1st century BC until the 13th or 14th century AD.[15]

Ancient inhabitants of Artsakh spoke a special dialect of the Armenian language; this is attested by the author of the Armenian grammar Stepanos Siunetsi who lived around AD 700.[16]

Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and Claudius Ptolemaeus all state that the border between Greater Armenia and Caucasian Albania is the river Cyrus (Kura).[17][18] Authoritative encyclopedias on antiquity also name Kura as the southern border of Albania.[19] Artsakh lies significantly to the south of this river. No contemporary evidence of its inclusion into Caucasus Albania or any other country exists until at least the end of the 4th century.[20]

Armenian historian Faustus of Byzantium wrote that during an epoch of the upheavals which followed the intrusion of the Persians into Armenia (about 370), Artsakh was among the provinces risen in revolt, whereas Utik has been seized by the Caucasus Albanians. Armenian military commander Mushegh Mamikonian defeated Artsakh in a massive battle, took many inhabitants of the region prisoner and hostage, and imposed a tribute on the rest. In 372 Mushegh defeated the Caucasus Albanians, took Utik from them, and restored the border along the Kura, "as was earlier".[21]

According to the "Geography" (Ashkharatsuyts) of 7th-century Armenian geographer Anania Shirakatsi, Artsakh was the 10th among the 15 provinces (nahangs) of Armenia, and consisted of 12 districts (gavars): Myus Haband (Second Haband, as opposed to Haband of Siunik), Vaykunik (Tsar), Berdadzor, Mets Arank, Mets Kvenk, Harjlank, Mukhank, Piank, Parsakank (Parzvank), Kusti, Parnes and Koght. However Anania predicts that even during his time Artsakh together with the neighboring regions "will tear away from Armenia". This is exactly what happened in 387 when Armenia was divided between the Roman Empire and Persia, when Artsakh, together with the Armenian provinces of Utik and Paytakaran, was attached to Caucasian Albania.

Mashtots and Aranshakhik periods

In 469 the kingdom of Albania was reformed into a Sassanid Persian marzpanate (frontier province). In the early 4th century Christianity spread in Artsakh. At the beginning of the 5th century, thanks to the creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots, an unprecedented rise of culture began in whole Armenia, in particular also in Artsakh, Mesrop Mashtots having founded one of the first Armenian schools at the Artsakh Amaras Monastery.

In the 5th century the eastern part of Armenia, including Artsakh, remained under Persian rule. In 451 the Armenians in response to the policy of compulsion of their Zoroastrian Persian overlords organized a powerful revolt known as the Vardan war. Artsakh took part in that war, its cavalry having particularly distinguished itself. After the suppression of the revolt by Persia, a considerable part of the Armenian forces took shelter in the impregnable fortresses and thick woods of Artsakh to continue further struggle against the foreign yoke.[22]

At the end of the 5th century, Artsakh and neighboring Utik united under the rule of the Aranshakhiks with Vachagan the Devout at the head (487–510s). Under the latter a considerable rise in culture and science is observed in Artsakh. According to the evidence of a contemporary, in those years in the land there were built as many churches and monasteries as there are days in a year. At the turn of the 7th century the Albanian marzpanate broke up into several small principalities. In the south, Artsakh and Utik created a separate Armenian principality, that of the Aranshakhiks. In the 7th century the Armenian Aranshakhiks were replaced by the Migranians or Mihranids, a dynasty of Persian origin which, becoming related with the Aranshakhiks, turned to Christianity and became rapidly Armenicized. In the second half of the 7th century in the initial period of the Arab dominion, political and cultural life in Artsakh did not cease. In the 7th and 8th centuries a distinctive Christian culture was shaped. The monasteries Amaras, Orek, Katarovank, Djrvshtik and others acquired a significance that transcended the local area and spread across the Armenian lands.

Armenian princedoms of Dizak and Khachen

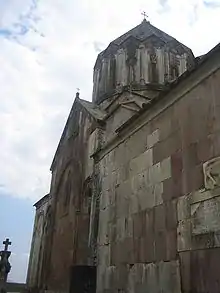

From the beginning of the 9th century, Armenian[23][24][25][26][27] princely houses of Khachen and Dizak were storing up strength. {The prince of Khachen, Sahl Smbatean} century became one of the most favorable periods for the land's flourishing. During this time, valuable architecture was constructed, such as the Church of Hovanes Mkrtich (John the Baptist) and its vestibule at the Gandzasar Monastery (1216–1260; the ancient residence of the Catholicos of Albania), the Dadi Monastery Cathedral Church (1214), and Gtchavank Cathedral Church (1241–1248). These churches are considered to be the masterpieces of the Armenian architecture.[28]

Turkic sovereignty

In the 11th century the Seljuk invasion swept over the Middle East, including Transcaucasia. Nomadic Oghuz Seljuk tribes that were brought with this invasion became dominant constituent in the ancestry of modern Azerbaijanis.[29] From the very beginning of their penetration in the region till the beginning of the 20th century these tribes used Mountainous Karabakh/Artsakh as their summer pastures, where they stayed for about four-five warmer months of year, and moreover, in fact owned the region.[30][31]

At the turn of 12th and 13th century Armenian dynasty of Zakarians took control over the Khachen, but its sovereignity was brief.[32]

In 30–40 years of the 13th century the Tatar and Mongols conquered Transcaucasia. The efforts of the Artsakh-Khachen prince Hasan-Jalal succeeded in partially saving the land from being destroyed. However, after his death in 1261, Khachen became subject to Tatars and Mongols. The situation became still more aggravating in the 14th century in the years of the subsequent Turkic federations the Qara Koyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu, having replaced the Tatars and Mongols.

Nomadic dominance in the Artsakh and the plains to the east of it continued in this period as well.[30] This vast area between the rivers of Kura and Araxes received Turkic name Karabakh (combination of "black" (Kara) in Turkic and "garden" (bakh) in Persian) with Artsakh corresponding to its mountainous part (Mountainous Karabakh/Nagorno-Karabakh in Soviet tradition). The name of Karabakh is first mentioned in the 14th century in the geographical work of Hamdallah Mustawi Nuzhat al-qulub and possibly derived from the name of some now extinct same-titled Turkic tribe.[33]

In the beginning of 16th century Karabakh was subjected to the Safavid Empire, which created there the same-titled administrative unit, comprising also some nearby territories and centered in the city of Ganja. In this period nomads of Karabakh coalesced in igirmi-dörd (literally, twenty-four in Azerbaijani) and otuz-iki (thirty-two) confederations that were among the key allies of Safavids in this part of empire. Christian Armenian denizens of Karabakh were subjected to the higher rates of taxes.[34]

The centuries-long subjection of the local Armenians to Muslim leaders, their relation with Turkic tribal elders and frequent cases of Turkic-Armenian-Iranian intermarriage resulted in Armenians adopting elements of Perso-Turkic Muslim culture, such as language, personal names, music, an increasingly humble position of women and, in some cases, even polygamy.[35]

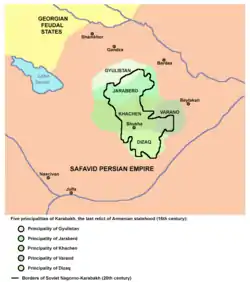

Armenian melikdoms

Princedom Khachen existed until 16th–17th century and has broken up into five small princedoms ("melikdoms"):

- Giulistan or Talish Melikdom included the territory from Ganja to the bed of the River Tartar.

- Dzraberd or Charaberd Melikdom was situated in the territory stretching from the River Tartar to the River Khachenaget.

- Khachen Melikdom existed in the territory from the River Khachenaget to the River Karkar.

- Varanda Melikdom included the territory from Karkar to the southern side of Big Kirs mountain.

- Dizak Melikdom stretched from the southern slope of Big Kirs mountain to the River Arax.

Those melikdoms were referred to as Khamsa, which means "five" in Arabic.[36] While subordinate to Safavid Persia's Karabakh beylerbeylik (ruled by Ziyad-oglu Qajars) the Armenian meliks were granted a wide degree of autonomy by Safavid Persia over Upper Karabakh, maintaining semi-quasi autonomous control over the region for four centuries,[37][38][39] while being under Persian domination. In the early 18th century, Persia's military genius and new ruler, Nadir shah took Karabakh out of control of Ganja khans in punishment for their support of the Safavids, and placed the region directly under his own control. At the same time, the Armenian meliks were granted supreme command over neighboring Armenian principalities and Muslim khans in Caucasus, in return for the meliks' victories over the invading Ottoman Turks in the 1720s.[40][41][42][43]

According to some historiographers of the 18th century, of those five meliks, only Melik-Hasan-Jalalyans – the rulers of Khachen – were local residents of Karabakh, while the other four had settled from neighboring provinces. Thus, Melik-Beglaryans of Gulistan were native Utis from the village of Nij in Shirvan; Melik-Israelyans of Jraberd were descendants of the melik of Siunik to south-east and hailed from the village of Magavuz in Zangezur; Melik Shahnazars of Varanda hailed from the region of Armenian Gegharkunik to the east and received the title of meliks from shah Abbas I in reward for their services; Melik-Avanyans of Dizak – were descendants of meliks of Lori, an Armenian princedom to north-west.[36][42][43] Modern western scholars Robert Hewsen and Cyril Toumanoff have demonstrated that all of these meliks were the descendants of the House of Khachen.[44]

Thanks to the meliks from the end of the 17th century in Artsakh there arouse and spread the idea of Armenian independence from Persia. Parallel with the armed struggle, Armenians in that period made diplomatic efforts, at first turning to Europe, then – to Russia. Such political and war leaders as Israel Ori, archimandrite Minas, the Catholicos of Gandsasar Yesai Jalalian, iuzbashis (the commanders of hundred; the capitans) Avan and Tarkhan become people leaders.

The absence of power and political instability in the 18th century in Persia created the threat to its integrity. Both Turkey and Russia expected to get its share from the possible breaking up of Persia, Turkey with this purpose striving for enlisting the support of the Dagestan mountaineers, Russia seeking its supporters among Armenians and Georgians.

In 1722, Peter the Great's Russo-Persian War (1722–23) began. At the very beginning the Russian forces succeeded in occupying Derbent and Baku. Armenians encouraged by the Russians, concluded the union with Georgians and collected an army in the Karabakh.[45] However their hopes were deceived. Instead of the promised help, Peter the Great advised the Armenians of Artsakh to leave their native places of residence and move to Derbent, Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran where the Russian power had recently been established in the war intending to consolidate its hold on the occupied. Khanates, attached to Caspia, Russia signed the treaty with Turkey, on July 12, 1724, giving the latter a free hand in the whole Transcaucasus (as far as Shamakha).

In the same year Ottoman troops invaded the land. Their main victim became the Artsakh Armenian population, who, headed by meliks, rose to struggle for its independence, never having received the promised support on Russian side. Yet, Peter the Great's march gave a new impulse to the struggle of the Armenians.

In the 1720s the in Karabakh formed host concentrated in three military camps or Skhnakhs (fortified place). The first of them, called the Great Skhnakh, was situated in the Mrav Mountains near the Tartar River. The second Pokr (Minor) Skhnakh was on the slope of the Kirs Mountain in the province of Varanda, and the third in the province of Kapan. Shkhnakhs, i.e. the Armenian host, possessed absolute power. That was a people army with the Council of military leaders, the Catholicos of Gandsasar also entering it and having a great influence. Proceed from the demands of wartime, meliks shared their power with iuzbashis, all of them having equal rights and obligations at the military councils. The Armenian host at the head of its leaders, Catholicos Yesai, iuzbashis Avan and Tarkhan resisted the Ottoman regular army for a considerably long time.

In 1733, the Armenians, now encouraged by another military genius, who happened to be Nadir Shah Of Persia, in one special appointed day massacred all Ottoman army that stood on the winter quartiers in Khamsa. After that former position of area has been restored.[46][47]

In gratitude for services rendered to it, Nadir Shah released the meliks of Khamsa from submission to khans of Ganja and appointed the governor above them Avan, melik of Dizak (the main organizer of plot 1733), having given it a title of khan. However, Avan-khan soon died[36]

Karabakh khanate

.jpg.webp)

In 1747, Turkic ruler Panah Ali Khan Javanshir from the Azeri Javanshir clan, by then already a successful naib and royal gérant de maison, found himself displeased with Nader Shah's attitude towards him during the latters later years of rule, and having gathered many of those deported from Karabakh in 1736, he returned to his homeland. Due to his reputation as a skillful warrior and his wealthy ancestor's legacy in Karabakh, Panah Ali proclaimed himself and was soon recognized throughout most of the region as a ruler (khan). The Shah sent troops to bring back the runaway however the order was never fulfilled: Nader Shah himself was killed in Khorasan in June of the same year. The new ruler of Persia, Adil Shah issued a firman (decree) recognizing Panah Ali as the Khan of Karabakh.[42]

Melik of Varanda Shahnazar II, who was at odds with other meliks, was the first to accept suzerainty of Panakh khan. Panakh khan founded the fortress of Shusha at a location, recommended by melik Shahnazar, and made it the capital of Karabakh khanate.

By this same time, the region and the whole wider Caucasus region was reasserted under firm Iranian suzerainty by Agha Mohammad Khan of the Qajar dynasty. However, he was assassinated some years afterwards, ever increasing the political unrest in the region.

The Meliks did not wish to reconcile to the new position. They desperately hoped for the aid of the Russians and had entered into a correspondence to Catherine II of Russia and its favorite Grigori Potyomkin. Potyomkin already gave orders, that "at an opportunity its (Ibrahim-khans of Shusha) area which is made of people Armenian to give in board national and thus to renew in Asia the Christian state".[48] But khan Ibrahim-Khalil (the son of Panakh-khan) learned about it. In 1785 he arrested the Dzraberd, Gulistan and Dizak meliks, and plundered Gandzasar monastery, and the Catholicos was planted in prison and poisoned. As a result of this the Khamsa melikdoms finally broke down.[36][49]

Ibrahim Khalil Khan, the son of Panah Ali Khan made the Karabakh khanate a semi-independent princedom, which only nominally recognized Persian rule.[42]

In 1797, Karabakh suffered the invasion of armies of Persian shah Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, who had just recently dealt with his Georgian subjects in the Tiflis. Shusha was besieged, but Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar was killed in the tent by own servants. In 1805 Ibrahim-khan signed the Kurekchay Treaty with Imperial Russia, represented by the Russian commander-in-chief in the war against Pavel Tsitsianov, according to which Karabakh khanate became the protectorate of Russia and the latter undertook to maintain Ibrahim-Khalil khan and his descendants as the ruling dynasty of Karabakh. However the following year Ibrahim-Khalil was killed by the Russian commandant of Shusha, who suspected that khan was trying to flee to Persia. Russia appointed Ibrahim-Khalil's son Mekhti-Gulu his successor.

In 1813, the Karabakh khanate, Georgia, and Dagestan passed to Imperial Russia by the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, before the rest of Transcaucasia was incorporated into the Empire in 1828 by the Treaty of Turkmenchay), following the two subsequent Russo-Persian Wars of the 19th century. In 1822, Mekhti-khan escaped to Persia. In 1826, in Karabakh the Persian armies with which was and Mekhti-khan have intruded; but they could not grasp Shusha which was protected desperately with Russian and Armenians, and have been expelled by Russian general Madatoff (himself Armenian from Karabakh by origin). The Karabakh khanate was dissolved, and the area became part of the Caspian oblast, and then Elizavetpol governorate within the Russian Empire.

Russian rule

The Russian Empire consolidated its power over the Karabakh Khanate following the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813 and Treaty of Turkmenchay of 1828, when following two Russo-Persian wars, Persia recognized Karabakh Khanate which dissolved in 1806, along with many other khanates, as part of Russia.

The Karabakh khanate dissolved in 1822. A survey prepared by the Russian imperial authorities in 1823, a year after and several years before the 1828 Armenian migration from Persia to the newly established Armenian Province, shows that all Armenians of Karabakh compactly resided in its highland portion, i.e. on the territory of the five traditional Armenian principalities, and constituted an absolute demographic majority on those lands. The survey's more than 260 pages recorded that the district of Khachen had twelve Armenian villages and no Tatar (Muslim) villages; Jalapert (Jraberd) had eight Armenian villages and no Tatar villages; Dizak had fourteen Armenian villages and one Tatar village; Gulistan had two Armenian and five Tatar villages; and Varanda had twenty-three Armenian villages and one Tatar village.[50][51] Only 222 Armenians migrated to lands that were part of the Karabakh province, in 1840.[52]

During the 19th century, Shusha becomes one of the most significant cities of Transcaucasia. By 1900 Susha was the fifth on size city of Transcaucasia; there was a theatre, printing houses, etc.; manufacture of carpets and trade were especially developed, since being there for a long time. According to first Russian-held census of 1823 conducted by Russian officials Yermolov and Mogilevsky, in Shusha were 1,111 (72.5%) Azerbaijani families and 421 (27.5%) Armenian families. Census of 1897 shows 25.656 inhabitants, from them of 56,5% of Armenians and 43,2% Azerbaijanis [53]

During the first Russian revolution in 1905, bloody armed clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis took place in the fields.

October Revolution, 1917

The establishment of the Russian Provisional Government happened after the Russian Revolution of 1917. Grand Duke Nicholas with the Special Transcaucasian Committee (особый Закавказский Комитет (ОЗАКОМ), osobyy Zakavkazskiy Komitet (OZAKOM)) committee established the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. Karabakh became part of the Transcaucasian Federation.

Following the October Revolution, a government of the local Soviet, led by ethnic Armenian Stepan Shaumyan, was established in Baku: the so-called National Council of Baku (November 1917 – July 31, 1918).

The Armenians under the Russian control devised a national congress in October 1917. The convention in Tiflis was concluded in September 1917 with delegates from the former Romanov realm. The Muslim National Councils (MNC) passed a law to organize the defense and devised a local control and administrative structure of the Transcaucasia. The Council also selected a 15-member permanent executive committee, known as the Azerbaijani National Council.

1918-1921 Armenian-Azerbaijani dispute

Independent states, May 1918

In May 1918 this soon dissolved into separate Democratic Republic of Armenia, Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, and Georgian Democratic Republic states.

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan claimed Mountainous Karabakh and had a strong reasoning for it.

Armenia regarded Mountainous Karabakh as its natural frontier, that constituted the easternmost part of Armenian Plateau and sharply contrasted with the Azerbaijani steppes to the east, so without Karabakh the physical unity of Armenia would be destroyed. Armenia also appealed to the historical ties of Karabakh to Armenia with former even being the last stronghold of Armenian statehood and the cradle of Armenian national movement during the Modern Era. Armenians constituted a majority in the mountainous parts of Karabakh. Strategically Armenia considered Karabakh as a barrier between Azerbaijan and Turkey.[54]

Similarly, Azerbaijan appealed to the history, as despite having some degree of autonomy, Mountainous Karabakh was part of Muslim khanates of Ganja and Karabakh. Plus, demographically Azeri constituted a majority in 7 of 8 uyezds of Elisabethpol guberniia and even in the heart of Mountainous Karabakh Muslims (Azeris and Kurds) formed a considerable minority. Thus, carving out the pockets of Christian concentration and addition of them to Armenia was regarded by Azerbaijan as injust, illogical and deterious to the welfare of all concerned. Azerbaijan did not regard the steppes and mountains of Karabakh as something separate, as tens of thousands of Azeri nomads circulated between them and in the case of separation of Highland and Lowland Karabakh, nomads would face certain ruin. These nomads, though never considered in census, regarded Karabakh as their homeland.[55] Strategically Mountainous Karabakh was important for Azerbaijan as well, since control of any other power over it would leave Azerbaijan very vulnerable. Economically Karabakh was tied to Azerbaijan with almost every major road going eastward to Baku, not westward to Yerevan.[56]

Ethnic and religious tension, March 1918

In March 1918, ethnic and religious tension grew and the Armenian-Azeri conflict in Baku began. Musavat and Ittihad parties were accused of Pan-Turkism by Bolsheviks and their allies. Armenian and Muslim militia engaged in armed confrontation, with the formally neutral Bolsheviks tacitly supporting the Armenian side. As a result, between 3,000 and 12,000 Azerbaijani's and other muslims were killed in what is known as the March Days.[57][58][59] Muslims were expelled from Baku, or went underground. At the same time the Baku Commune was involved in heavy fighting with the advancing Ottoman Caucasian Army of Islam in and around Ganja. Major battles occurred in Yevlakh and Agdash, where the Turks routed and defeated Dashnak and Russian Bolshevik forces.

In these circumstances the government of Azerbaijan declared the incorporation of Karabakh into the newly established Azerbaijan Democratic Republic of Baku and Yelizavetpol Gubernias. However, the Nagorno-Karabakh and Zangezur rejected to recognize the jurisdiction of the Azerbaijani Republic. Here the two Armenian national uyezd (district) councils took the power into their hands, organised and headed the struggle against Azerbaijan.

Armenian "People's Government", July 1918

On July 22, 1918, the First Congress of the Armenians of Karabakh was convened, which proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh an independent administrative-political unit, elected the National Council as well as the People's government. Peoples Government of Karabakh had five administrators in the following areas:

- Foreign and internal affairs – Yeghishe Ishkhanian)

- Military affairs – Harutiun Toumanian)

- Communications – Martiros Aivazian

- Finances – Movses Ter-Astvatsatrian

- Agronomy and justice – Arshavir Kamalyan

Prime-minister of the government was Yeghishe Ishkhanian, the secretary – Melikset Yesayan. The government published the newspaper "Westnik Karabakha".[60]

In September, at the 2nd Congress of the Armenians of Karabakh the People's Government was renamed into the Armenian National Council of Karabakh. In essence, its structure remained the same:

- Justice Department – Commissar Arso Hovhannisian, Levon Vardapetian

- Military Department – Harutiun Tumian (Tumanian)

- Department of Education – Rouben Shahnazarian

- Refugees Department – Moushegh Zakharian

- Control Department – Anoush Ter-Mikaelian

- Department of Foreign Affairs – Ashot Melik-Hovsepian.[61][62]

On July 24, the Declaration of the People's government of Karabakh was adopted which set forth the objectives of the newly established state power.[63]

Armistice of Mudros, October 1918

On October 31, 1918, the Ottoman Empire admitted its defeat in World War I, and its troops retreated from Transcaucasia. British forces replaced them in December and took the area under its control.

The British mission

The government of Azerbaijan for this once tried to capture Nagorno-Karabakh with the help of the British. The new borders of Transcaucasia could not be defined without the agreement of Great Britain. Stating that the fate of the disputable territories must be solved at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, the British command in reality did everything for incorporating Nagorno-Karabakh into Azerbaijan long before the final resolution of the problem. Establishing a full control over the export of the Baku oil, the British sought the final secession of Transcaucasia from Russia; Azerbaijan, as it was supposed, was to play a role of an advanced post of the West in the South Caucasus to create barriers to the sovietization of the region.

On this account the policy of the allied powers in the relation with Transcaucasia had a pro-Azerbaijani trend. The solution of the Karabakhian problem was dragged out rather calculating on the development of the military-political situation that would be favourable for Azerbaijan, therefore the change of the ethnic structure of Nagorno-Karabakh.

On January 15, 1919, the Azerbaijani government with "the knowledge of the British command" appointed Khosrov bey Sultanov governor-general of Nagorno-Karabakh, simultaneously laying an ultimatum to the Karabakhian National Council to recognize the power of Azerbaijan. On February 19, 1919, the 4th Congress of the Armenian population of Karabakh was convened in Shushi, which decisively rejected this ultimatum of Azerbaijan and expressed protest in connection with the appointment of Sultanov governor-general. The resolution adopted by the congress says, "Insisting on the principle of the self-determination of a people, the Armenian population of Karabakh respects the right of the neighbouring Turkish people for self-determination and together with this decisively protests against the attempts of the Azerbaijani government to eliminate this principle in the relation of Nagorno-Karabakh, which never will admit the power of Azerbaijan over it".[64]

In the connection with the appointment of Sultanov the British mission came out with an official notification, which stated, that "by the British command's consent Dr. Khosrov Bek Sultanov is appointed provisional governor of Zangezur, Shusha, Jivanshir and Jebrail useds [sic]. The British Mission finds it necessary to confirm that belonging of the mentioned districts to one or another unit must be solved at a Peace Conference".[65]

The National Council of Karabakh gave the following answer:

The National Council of the Armenians of Karabakh with its full complement, in common with the commanders of all the districts of Karabakh, having discussed the fact of appointing general-governor of the government of Azerbaijan, came to the conclusion that the Armenian Karabakh cannot accept such a fact, as the Armenian people of Karabakh considers the dependence on the government of Azerbaijan, in whatever form it might be, unacceptable due to those violence and violations of rights, which the Armenian people was systematically subjected to by the Azerbaijani government until recently wherever it connected its position with this government. The Armenian Karabakh showed the whole world that it in fact did not recognize and does not recognize within its borders the power of the Azerbaijani government as it had been decided recently by the Congress of the Armenians of Karabakh. Proceeding from the fact that the British command recognizes the Armenian Karabakh such a territory that is not subordinated to any state before the solution of the Peace Conference, therefore and in particular to Azerbaijan, the National Council considers the appointment of the British general-governor the only acceptable form for the government of the Armenian Karabakh, and it asks the mission to solicit the Supreme English Command".[66]

However in spite of the Karabakhi people's protests the British commandment continued to assist and support the Azerbaijani Government in realizing the policy of incorporation of Armenian Karabakh into Azerbaijan. The British troops' commander in Baku Colonel Schatelwort (Digby Shuttleworth ?) stated to the Karabakhian people:

I warn, that any excesses against Azerbaijan and its general-governor are performance against England. We are so strong, that we can force you to obey".[67]

Shusha, April 1919

Unable to force Nagorno-Karabakh to it knees by threats or by the help of the armed forces Schatelwort personally arrived at Shusha late in April 1919 to compel the National Council of Karabakh to recognize the power of Azerbaijan. On April 23, in Shusha the Fifth Congress was convened which rejected the Schatelwort's demands. The congress has declared, that

"Azerbaijan always acted as the helper and the accomplice in the atrocities which are carried out by Turkey concerning Armenians in general and Karabakhs of Armenians in particular ".

It has accused Azerbaijan of robbery, murders and hunting for Armenians on roads, and that it "aspires to destroy Armenians as the unique cultural element, gravitating not to the East, and to the Europe ". Therefore resolution declared, that any program having any attitude to Azerbaijan is unacceptable for Armenian.[68]

Having received a refusal from the Fifth Congress, Sultanov decided to subordinate Nagorno-Karabakh by means of the armed forces. Almost the whole army of Azerbaijan was concentrated at the Nagorno-Karabakh borders. In the beginning of June Sultanov has tried to borrow the Armenian quarters of Shusha, attacked positions of Armenians and has organized pogroms the Armenian villages. So, nomads under leadership of Sultanov's brother completely massacred village Gayballu. 580 Armenians in total were lost...[69][70] The English troops withdrew from Nagorno-Karabakh to give the Azerbaijani troops a free hand.

On those days there was concluded the agreement to convene the Sixth Congress of the Karbaghi Armenians, at which the representatives of the English Mission and Azerbaijani government were to take part. The main objective of the Congress was the discussion of the interrelations of Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan before the convention of the Peace Conference in Paris. However the representatives of the English mission and the government of Azerbaijan arrived at the Congress, after it had finished its work and the negotiations did not take place. To find out whether Nagorno-Karabgh would be able to defend its independence in case of war, at the Congress the Commission was established which came to the conclusion, that the Karabakhians would not be able to do so. In such circumstances the Congress, being under the threat of the armed assault form Azerbaijan, was compelled to start negotiations.

Final solution to peace conference, August 1919

Eager to win time and to concentrate the forces available, the Congress of the Armenians of Karabakh convened on August 13, 1919, concluded the agreement on August 22 according to which Nagorno-Karabgh considered itself to be fully within the borders of the Azerbaijani Republic till the final solution of the problem at Peace Conference in Paris. However the Azerbaijan armies are there in structure of a peacetime. Azerbaijan cannot enter into area of an army without the permission of National Council. Disarmament of the population stops before peace conference.[71]

In February, Azerbaijan has started to focus around Karabakh military parts and irregular groups. The Karabakh Armenians declared, that Sultanov "has organized large gangs of Tatars, Kurds, prepares grandiose massacre of Armenians (…) On roads kill travellers, rape women's, the cattle steal up. Proclaimed the economic blockade of Karabakh. Sultanov is declared demands entry of garrison in heart of Armenian Karabakh: Varanda, Dzraberd, break these the agreement of VII Congress".[72]

1920–1921

On February 19, 1920, Sultanov turned to the National Council of the Karabakhi Armenians with the demand "urgently to solve the question of the final incorporation of Karabakh into Azerbaijan".[73]

From February 23 until March 4, 1920, the Eighth Congress of Karabakhi Armenians was held and it rejected the demand of Sultanov. The Congress has accused Sultanov of numerous infringements of the peace agreement, entry of armies in Karabakh without the permission of National Council and the organization of murders of Armenians, in particular the massacre accomplished on February 22 in Khankendy, Askeran and on road Shusha-Evlakh.[74]

However, in all these events, the aspirations and wishes of Azerbaijani population of Karabakh were continuously violated by Armenian inhabitants "who had no right to represent in its Congress the will of the entire population of the region"[73]

In accordance with the decision of the Congress the diplomatic and the military representatives of the allied states of the Entente, three Transcaucasian republics and the provisional governor-general were informed that "the repetition of the events will compel the Armenians of Nagorno- Karabakh to turn to the appropriate means for defense."[75][76][77][78]

Nagorno-Karabakh war 1920

In March–April 1920 there was a short war between Azerbaijan and Armenia for Nagorno-Karabakh. It began on March 22 (on Nowruz) when Armenian forces broke the armistice and unexpectedly attacked Askeran and Khankendi. The Armenians assumed that the Azerbaijanians would be celebrating Nowruz and would therefore not be prepared for defense, but an attempted attack on the Azerbaijan garrison in Shusha failed because of poor coordination. In response Azerbaijan forces armies burnt the Armenian part of Shusha and massacred the population. "The most beautiful Armenian city has been destroyed, crushed to its foundations; we have seen corpses of women and children in wells" – recollects Soviet communist leader Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze.[79]

The Armenian sources name different figures of victims among Armenians, from 500 person at R. Hovannisian[80] up to 35 thousand; ordinarily name figure in 20–30 thousand; number of the burnt houses estimate from (R. Hovannisian) 2 thousand up to 7 thousand (ordinarily named figure).[81] According to Greater Soviet Encyclopedia, during military events 20% of the population of the Nagorno-Karabakh were lost, (that at absolute calculation gives up to 30 thousand persons); mainly Armenians (which 94% of the population of area in general ade)[82][83] Pogrom in Shusha was kept in historical memory of the Karabakh Armenians as largest of the accidents gone through by them.

As a result of rout, Shusha has come to the pithiest situation. Its population was reduced up to 9.000, and by the end of 20th and up to 5.000 person[79] (and so never and has not risen above 17.000 in 1989).[84] Nadezhda Mandelstam so describes Shusha 20th years: " everywhere the same: two houses without a roof, without windows, without doors. (...)Speak, that after slaughter all wells have been hammered by corpses. If who has escaped, ran from this city of death. On all mountainous streets we did not see and have not met any person. Only below – on a market square – pottered about small group to people, but among them there was no Armenian, only muslims ".[85]

The course of the war was as follows. On April 3, Azerbaijanians have borrowed Askeran (grasped on March 22 by the Armenian insurgents). On April 7, being based on Shusha, the Azerbaijan army has led approach to the south. At the same time there was an approach in the north, on Giulistan. By April 12, the Azerbaijan approach has been stopped in Giulistan – under Chaikend, in the Varanda – under Keshishkend and Sigankh. In Khachen to Armenians in general it was possible to beat off successfully from the Azerbaijanians come from Agdam, and Azerbaijanians have only destroyed some villages in a valley of river Khachen, to northeast from Askeran. Against Azerbaijan all armed manned population of Karabakh (30.000) operated; Armenia officially denied the participation in operations, that mismatched the validity.[86] However, the Armenian armies on Zangezur front, under command of the general Dro (Drastamat Kanayan) crushed the Azerbaijan barriers and broke in Karabakh. The strategic situation had sharply changed, and Armenians have started to prepare for storm of Shusha.[87]

Armenian declaration, April 1920

In April 1920, the Ninth Congress of the Karabakhi Armenians was held which proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh an essential part of Armenia. The concluding document reads:

- "To consider the agreement, which was concluded with the government of Azerbaijan on behalf of the Seventh Congress of Karabakh, violated by the latter, in view of the organized attack of the Azerbaijani troops on the civilian Armenian population in Shusha and villages.

- To proclaim the joining of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia as an essential part of Armenia".[75]

But, with the direct intervention of Russian troops, Azerbaijan regained control of the area.

Soviet era, 1921–1991

On July 4, 1921, the Plenum of the Caucasian Bureau of the Central Committee of Russian Communist Party decided that Karabakh would be integrated to Armenia. However, on the next day, July 5, 1921, Stalin intervened and thus it was decided that Karabakh be retained in Soviet Azerbaijan – this decision was taken without local deliberation or plebiscite.[88][89][90][91] As a result, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) was established within the Azerbaijan SSR in 1923. Most of the decisions on the transfer of the territories, and the establishment of new autonomous entities, were made under pressure from Joseph Stalin, who is still blamed by Armenians for this decision made against their national interests

"The Soviet Union created the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region within Azerbaijan in 1924 when over 94 percent of the region's population was Armenian. (The term Nagorno-Karabakh originates from the Russian for "mountainous Karabakh.") As the Azerbaijani population grew, the Karabakh Armenians chafed under the discriminatory rule, and by 1960 hostilities had begun between the two populations of the region."

For 65 years of the NKAO's existence, the Karabakh Armenians felt they were the object of various restrictions on the part of Azerbaijan. The essence of Armenian discontent lay in the fact that the Azerbaijani authorities deliberately severed the ties between the oblast and Armenia and pursued a policy of cultural de-Armenization in the region, of planned Azeri settlement, squeezing the Armenian population out of the NKAO and neglecting its economic needs.[92] The census of 1979 showed that the general number of inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region was counted as 162,200 persons, from them 123,100 Armenians (75.9%) and 37,300 Azerbaijanians (22.9%)[93] Armenians marked this fact, comparing with it with data of 1923 (94% of Armenians). In addition to that they marked, that " to 1980 in Nagorno-Karabakh 85 Armenian villages (30%) have been liquidated and none at all Azerbaijanian "[94] Also, Armenians accused the government of Azerbaijan "to the purposeful policy of discrimination and replacement". They believed that Baku's plan was to supersede absolutely all Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh.

Azerbaijani residents of the NKAO, meanwhile, were complaining about discrimination by the Armenian majority of the autonomous oblast and their economic marginalization.[95] De Waal in his Black Garden points out that NKAO economically was worse off than Armenia SSR. However, he adds that economically Azerbaijan SSR overall was poorest in South Caucasus; nevertheless, NKAO's economic indicators were better than overall Azerbaijan, which might be a motivation for Karabakh Armenians to join Armenia SSR.[96] With the beginning of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the question of Nagorno-Karabakh re-emerged. On February 20, 1988, the Oblast Soviet of the NKAO weighed up the results of an unofficial referendum on the reattachment of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, held in the form of a petition signed by 80,000 people. On the basis of that referendum, the session of the Oblast Soviet of Nagorno-Karabakh adopted the appeals to the Supreme Soviets of the USSR, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, asking them to authorize the secession of Karabakh from Azerbaijan and its attachment to Armenia.[92]

It has caused indignation among the neighboring Azerbaijan population, which began to gather crowds to go and "put things in order" in Nagorno-Karabakh. On February 24, 1988, a direct confrontation between Armenians and gone "to put things in order" the Azerbaijanians, occurred near Askeran (border of Nagorno-Karabakh, on the road Stepanakert – Agdam) degenerated into a skirmish. During the clashes, which left about 50 Armenians wounded, a local policeman, in accordance with information from International Historical-enlightenment Human rights Society – Memorial[97] he was an Azeri, shot dead two Azerbaijanis – Bakhtiyar Guliyev, 16, and Ali Hajiyev, 23. On February 27, 1988, while speaking on Central TV, the USSR Deputy Prosecutor General A. Katusev mentioned the nationality of those killed. Within hours, a pogrom against Armenian residents began in the city of Sumgait, 25 km north of Baku, where many Azerbaijani refugees resided. The pogrom lasted for three days. The exact figures for the dead are disputed. The official investigation reported 32 deaths – 6 Azerbaijanis and 26 Armenians,[98] while the US Library of Congress places the number of Armenian victims at over 100.[99]

A similar attack on Azerbaijanis occurred in the Armenian towns of Spitak,[99] Gugark, during the Gugark pogrom[100] and others. Azerbaijani sources put the number of Azerbaijanis killed in clashes in Armenia at 216 in total, including 57 women, 5 infants and 18 children of different ages.[92] KGB of Armenia, however, approves, that it has tracked the destiny of all those from the Azerbaijan list-of-dead and the majority of them – earlier died, living in other regions USSR, from the earthquake of 1988 in Spitak etc.; the figure of Armenian KGB – 25 killed – originally was not challenged and in Azerbaijan.[101][102]

Large numbers of refugees left Armenia and Azerbaijan as pogroms began against the minority populations of the respective countries. In the fall of 1989, intensified inter-ethnic conflict in and around Nagorno-Karabakh led Moscow to grant Azerbaijani authorities greater leeway in controlling that region. The Soviet policy backfired, however, when a joint session of the Armenian Supreme Soviet and the National Council, the legislative body of Nagorno-Karabakh, proclaimed the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia. In mid-January 1990, Azerbaijani protesters in Baku went on a rampage against remaining Armenians. Moscow intervened only after there were almost no Armenian population left in Baku, sending army troops, who violently suppressed the Azerbaijan Popular Front (APF) and installed Mutalibov as president. The troops reportedly killed 122 Azerbaijanis in what is known as Black January in quelling the uprising, and Gorbachev denounced the APF for striving to establish an Islamic Republic.

In a December 1991 referendum, that was taking place along with similar referendums all around the USSR, and boycotted by most of the local Azerbaijanis, the yet majority population of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh approved the creation of an independent state. However, the Constitution of the USSR was the instrument in accordance to which only the 15 Soviet Republics could vote for independence and Nagorno-Karabakh was not one of the Soviet Republics. A Soviet proposal for enhanced autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan satisfied neither side and subsequently led to the eruption of war between Armenia-backed Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan.

Nagorno-Karabakh War, 1991

The struggle over Nagorno-Karabakh escalated after both Armenia and Azerbaijan attained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. In the post-Soviet power vacuum, military action between Azerbaijan and Armenia was heavily influenced by the Russian military. Extensive Russian military support was exposed by the Head of the Standing Commission of the Russian Duma, General Lev Rokhlin, who was subsequently allegedly killed by his wife in unknown circumstances. He had claimed that munitions (worth one billion US dollars) had been illegally transferred to Armenia between 1992 and 1996.[103] According to Armenian news agency Noyan Tapan, Rokhlin openly lobbied for the interests of Azerbaijan.[104] According to The Washington Times, Western intelligence sources said that the weapons played a crucial role in Armenia's seizure of large areas of Azerbaijan. Other Western sources dispute that assessment, because Russia continued to provide military support to Azerbaijan, as well, throughout the military conflict.[105] Russian Minister of Defense Igor Rodionov in his letter to Aman Tuleyev, Minister of cooperation with CIS countries, said that a Defense Ministry commission had determined that a large quantity of Russian weapons, including 84 T-72 tanks and 50 armored personnel carriers, were illegally transferred to Armenia between 1994 and 96, after the ceasefire, for free and without authorization by the Russian government.[106] The Washington Times article suggested that Russia's military support for Armenia was aimed to force "pro-Western Azerbaijan and its strategic oil reserves into Russia's orbit".[107] Armenia has officially denied any such weapons delivery.[103]

Both sides used mercenaries. Mercenaries from Russia and other CIS countries fought on the Armenian side,[108] and some of them were killed or captured by the Azerbaijan army.[109] According to The Wall Street Journal, Azerbaijani President Heydər Əliyev recruited thousands of mujahedeen fighters from Afghanistan (and mercenaries from Iran and elsewhere) and brought in even more Turkish officers to organize his army.[110] The Washington Post discovered that Azerbaijan hired more than 1,000 guerrilla fighters from Afghanistan's radical prime minister, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Meanwhile, Turkey and Iran supplied trainers, and the republic also was aided by 200 Russian officers who taught basic tactics to Azerbaijani soldiers in the northwest city of Barda.[111] Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev, generally considered a notorious terrorist,[112] personally engaged Armenian forces in NKR. According to EurasiaNet, unidentified sources have stated that Arab guerrilla Ibn al-Khattab joined Basayev in Azerbaijan between 1992 and 1993, although that is dismissed by the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense.[113] In addition, officers from the Russian 4th Army participated in combat missions for Azerbaijan on a mercenary basis.[114]

According to Human Rights Watch, "from the beginning of the Karabakh conflict, Armenia provided aid, weapons, and volunteers which were taken from Russia. In February 1992, 161 ethnic Azerbaijani civilians were murdered by ethnic Armenian armed forces in what is known as the Khojaly Massacre. Armenian involvement in Karabakh escalated after a December 1993 Azerbaijani offensive. The Republic of Armenia began sending conscripts and regular Army and Interior Ministry troops to fight in Karabakh. In January 1994, several active-duty Armenian Army soldiers were captured near the village of Chaply, Azerbaijan. To bolster the ranks of its army, the Armenian government resorted to press-gang raids to enlist recruits. Draft raids intensified in early spring, after Decree no. 129 was issued, instituting a three-month call-up for men up to age 45. Military police would seal off public areas, such as squares, and round up anyone who looked to be draft age".[115]

By the end of 1993, the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh had caused thousands of casualties and created hundreds of thousands of refugees on both sides. In a national address in November 1993, Əliyev stated that 16,000 Azerbaijani troops had died and 22,000 had been injured in nearly six years of fighting. The UN estimated that just under 1 million Azerbaijani[116] refugees and internally displaced person were in Azerbaijan at the end of 1993. Mediation was attempted by officials from Russia, Kazakhstan, and Iran, among other countries, and by organizations, including the UN and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, which began sponsoring peace talks in mid-1992. All negotiations met with little success, and several cease-fires broke down. In mid-1993, Əliyev launched efforts to negotiate a solution directly with the Karabakh Armenians, a step which Elchibey had refused to take. Əliyev's efforts achieved several relatively long cease-fires in Nagorno-Karabakh, but outside the region Armenians occupied large sections of southwestern Azerbaijan near the Iranian border during offensives in August and October 1993. Iran and Turkey warned the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to cease the offensive operations that threatened to spill over into foreign territory. The Armenians responded by claiming that they were driving back Azerbaijani forces to protect Nagorno-Karabakh from shelling.

In 1993, the UN Security Council called for Armenian forces to cease their attacks on and occupation of a number of Azerbaijani regions. In September 1993, Turkey strengthened its forces along its border with Armenia and issued a warning to Armenia to withdraw its troops from Azerbaijan immediately and unconditionally. At the same time, Iran was conducting military maneuvers near the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic in a move widely regarded as a warning to Armenia.[117] Iran proposed creation of a twenty-kilometer security zone along the Iranian-Azerbaijani border, where Azerbaijanis would be protected by Iranian firepower. Iran also contributed to the upkeep of camps in southwestern Azerbaijan to house and feed up to 200,000 Azerbaijanis fleeing the fighting.

Fighting continued into early 1994, with Azerbaijani forces reportedly winning some engagements and regaining some territory lost in previous months. In January 1994, Əliyev pledged that in the coming year occupied territory would be liberated and Azerbaijani refugees would return to their homes. At that point, Armenian forces held an estimated 14 percent of the area recognized as Azerbaijan, with Nagorno-Karabakh proper comprising 5 percent.[118]

However, during the first three months of 1994 the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army started a new offensive campaign and captured some areas thus creating a wider safety and buffer zone around Nagorno-Karabakh. By May 1994 the Armenians were in control of 20% of the territory of Azerbaijan. At that stage the Government of Azerbaijan for the first time during the conflict recognised Nagorno-Karabakh as a third party of the war and started direct negotiations with the Karabakhi authorities. As a result an unofficial cease-fire was reached on May 12, 1994, through Russian negotiation, and continues today.

As a result of the war for Nagorno-Karabakh safety and independence, Azerbaijanis were driven out of Nagorno-Karabakh and territories adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh. Those are still under control of the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenian military. With the support of Soviet/Russian military forces, Azerbaijanis forced out tens of thousand Armenians from Shahumyan region. Armenians remain in control of the Soviet-era autonomous region, and a strip of land called the Lachin corridor linking it with the Republic of Armenia; as well as the so-called 'security zone'—strips of territory along the region's borders that had been used by Azerbaijani artillery during the war. The Shahumyan region remains under the control of Azerbaijan.

Timeline

- The exact date of the establishment of the Province of Artsakh is not known, but it's believed to be sometime before 189 BC.

- The Hasan-Jalalyan dynasty branches out sometime in the 16th century.

- The Russian Empire occupies the lands, but they're formally annexed only in 1813 by the Treaty of Gulistan.

- Shemakha Governorate was renamed to Baku Governorate in 1859.

- The Transcaucasian Democratic Federal Republic was a multi-national entity established by Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian leaders.

- Treaty of Batum

- Armistice of Mudros

- Seventh Assembly of Mountainous Karabakh

- British withdrawal.

- Eighth Assembly of Mountainous Karabakh

- General Dro (Drastamat Kanayan) takes parts of Mountainous Karabakh on behalf of the Republic of Armenia.

- Ninth Assembly of Mountainous Karabakh

- Azerbaijan is invaded by the Red Army.

-

.svg.png.webp) Azerbaijan SSR's revolutionary committee declares Mountainous Karabakh to be transferred to

Azerbaijan SSR's revolutionary committee declares Mountainous Karabakh to be transferred to .svg.png.webp) Armenian SSR.

Armenian SSR. - Kavbiuro decides to leave Mountainous-Karabakh within

.svg.png.webp) Azerbaijan SSR.

Azerbaijan SSR. - Declared, and then implemented in November of 1924.

- Operation Ring

- The Armenians of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast declare their independence.

- Azerbaijan abolishes the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast.

- Bishkek Protocol ceasefire.

- 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement.

References

- Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies: JSAS., Volume 8. University of Michigan, 1997, p 54.

- Robert H. Hewsen, "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians", in Thomas J. Samuelian, ed., Classical Armenian Culture: Influences and Creativity. Pennsylvania: Scholars Press, 1982. "What do we know of the native population of these regions — Arc'ax and Utik — prior to the Armenian conquest? Unfortunately, not very much. Greek, Roman, and Armenian authors together provide us with the names of several peoples living there, however — Utians, in Otene, Mycians, Caspians, Gargarians, Sakasenians, Gelians, Sodians, Lupenians, Balas[ak]anians, Parsians and Parrasians — and these names are sufficient to tell us that, whatever their origin, they were certainly not Armenian. Moreover, although certain Iranian peoples must have settled here during the long period of Persian and Median rule, most of the natives were not even Indo-Europeans."

- Susan M. Sherwin-White, Amalie Kuhrt. From Samarkhand to Sardis: A New Approach to the Seleucid Empire, p. 16. "There are many problems over the boundaries of Seleucid Armenia, which have not be studied, but could be illuminated by the accounts of the expansion of the Armenian Kingdom beyond the limits of Armenia after Antiochus III's defeat by the Romans in 189. The frontiers on the south and south-west are roughly, the Seleucid satrapies of Seleucid Cappadocia, Mesopotamia and Syria, and of Commagene; in the north, Iberia in the Lower Caucasus, north of the river Araxes and Lake Sevan, and western Media Atropatene — roughly equivalent to modern Azerbaijan; in the north-west, separating Armenia from the Black Sea, were independent tribes"

- George A. Bournoutian. A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present), p. 33. "After the death of Alexander, the Armenians maintained this stance towards the governors imposed by the Seleucids. The Yervandunis gained control of the Arax Valley, reached Lake Sevan, and constructed a new capital at Yervandashat."

- Elisabeth Bauer-Manndorff. Armenia: Past and Present, p. 54. "Armenia Major, under the rule of the Ervantids consisted of the central area east of the upper Euphrates, around Lake Van and the Araxes as far as Lake Sevan."

- Robert H. Hewsen, "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians", in Thomas J. Samuelian, ed., Classical Armenian Culture: Influences and Creativity. Pennsylvania: Scholars Press, 1982. "From Strabo we learn that under King Artashes (188-ca. 161 B. C.), the Armenians expanded in all directions at the expense of their neighbors. Specifically we are told that at this time they acquired Caspiane and 'Phaunitis', the second of which can only be a copyist's error for Saunitis, i. e. the principality of Siwnik '.Thus, it was only under Artashes, in the second century B. C., that the Armenians conquered Siwnik' and Caspiane and, obviously, the lands of Arc'ax and Utik', which lay between them. These lands, we are told, were taken from the Medes. Mnac'akanyan's notion that these lands were already Armenian and were re-conquered by the Armenians at this time thus rests on no evidence at all and indeed contradicts what little we do know of Armenian expansion to the east."

- Trever, Kamilla (1959). Очерки по истории и культуре Кавказской Албании IV в. до н. э.- VII в. н. э. [Essays on the History and Culture of Caucasian Albania, IV BC-VII AD.].

- Новосельцев, А. П. "К вопросу о политической границе Армении и Кавказской Албании в античный период" [On the Political Border of Armenia and Caucasian Albania in Antique Period]. Кавказ и Византия [Caucasus and Byzantium] (1): 10–18.

- Thomas J. Samuelian. "Armenian Origins: An Overview of Ancient and Modern Sources and Theories" (PDF).

- Movses Khorenatsi. "History of Armenia". I.12, II.8.

- Movses Kaghankatvatsi, "History of Aluank". I.4.

- Movses Khorenatsi, "History of Armenia," I.12

- Movses Kaghankatvatsi, "History of Aluank". I.15.

- Strabo, "Geography", 11.14.4

- Кавказ Мемо.Ру :: kavkaz-uzel.ru :: Армения, Нагорный Карабах | На территории Нагорного Карабаха обнаружены руины древнего армянского города

- Историко-политические аспекты карабахского конфликта

- Claudius Ptolemaeus. Geography, 5, 12

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 6, 39

- Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Volume I. Stuttgart 1894". p. 1303

- Nagorno Karabakh: History

- Faustus of Byzantium, IV, 50; V,12

- Elishe. History, 276–277

- "Armenia". Encyclopædia Britannica. "A few native Armenian rulers survived for a time in the Kiurikian kingdom of Lori, the Siuniqian kingdom of Baghq or Kapan, and the principates of Khachen (Artzakh) and Sasun."

- Abū-Dulaf Misʻar Ibn Muhalhil's Travels in Iran (circa A.D. 950) / Ed. and trans. by V. Minorsky. — Cairo University Press, 1955. — p. 74:"Khajin (Armenian Khachen) was an Armenian principality immediately south of Barda'a."

- Howorth, Henry Hoyle (1876). History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 14

- "Russian scholar V. Shnirelman: Khachen was a medieval Armenian feudal principality in the territory of modern Karabakh, which played a significant role in the political history of Armenia and the region in the 10th–16th centuries". В.А. Шнирельман, Албанский миф, 2006, Библиотека «Вeхи»

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica by Robert MacHenry, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc, Robert MacHenry, (1993) p. 761

- А. Л. Якобсон, Из истории армянского средневекового зодчества (Гандзасарский монастырь)

- "Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Olcott, M.; Malashenko, M. (1998). Традиционное землепользование кочевников исторического Карабаха и современный армяно-азербайджанский этнотерриториальный конфликт (Анатолий Ямсков) [The Traditional Land-use of the Nomads of Historical Karabakh and the Modern Armenian-Azerbaijani Ethno-territorial Conflict (by Anatoly N. Yamskov)]. Фактор этноконфессиональной самобытности в постсоветском обществе [The Factor of Ethno-confessional Identity in the Post-Soviet Society]. Московский Центр Карнеги (The Moscow Center of Carnegie). pp. 179–180. ISBN 0-87003-140-6.

This seasonal coexistence in the mountains of historical Karabakh with a sedentary Armenian population and a nomadic Turkic one, as well as some Kurdish, completely assimilated by Azerbaijanis in the 19th–20th centuries, arose a long time ago, simultaneously with the great movement of nomadic pastoralists into the plains of Azerbaijan.

Указанная ситуация сезонного сосуществования в горах исторического Карабаха оседлого армянского и кочевого тюркского населения, а также частично и курдского, полностью ассимилированного азербайджанцами в XIX—XX вв., возникла очень давно, одновременно с массовым проникновением кочевых скотоводов на равнины Азербайджана.

- Yamskov, A. N. (June 22, 2014). "Ethnic Conflict in the Transcausasus: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh". Theory and Society (published October 1991). 20 (No. 5, Special Issue on Ethnic Conflict in the Soviet Union): 650 – via JSTOR.

The Azeri conception of Karabakh as an inseparable part of Azerbaijan is based on other considerations than the oblast's ethnic composition. The Armenians have resided in Karabakh for a long time, and they represented an absolute majority of its population at the time that the autonomous oblast was formed. However, for centuries the entire high mountain zone of this region belonged to the nomadic Turkic herdsmen, from whom the Khans of Karabakh were descended. Traditionally, these direct ancestors of the Azeris of the Agdamskii raion (and of the other raions between the mountains of Karabakh and the Kura and Araks Rivers) lived in Karabakh for the four or five warm months of the year, and spent the winter in the Mil'sko-Karabakh plains. The descendants of this nomadic herding population therefore claim a historic right to Karabakh and consider it as much their native land as that of the settled agricultural population that lived there year-round.

- Еремян, С. Т. (1961). "Армения накануне монгольского завоевания" [Armenia on the Eve of the Mongol Conquest]. Атлас Армянской ССР [The Atlas of Armenian SSR]. Yerevan. pp. 102–106.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1943). Tadhkirt Al-muluk. p. 174.

- Ghereghlou, Kioumars. "Cashing in on land and privelege for the welfare of the shah: monetisation of tiyul in ealy Safavid Iran and Eastern Anatolia". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. 68 (1): 110.

- Stepan Lisitsian. Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh; p. 44

- Raffi. Melikdoms of Khamsa

- Britannica:"In mountainous Karabakh a group of five Armenian maliks (princes) succeeded in conserving their autonomy and maintained a short period of independence (1722–30) during the struggle between Persia and Turkey at the beginning of the 18th century; despite the heroic resistance of the Armenian leader David Beg, the Turks occupied the region but were driven out by the Persians under the general Nādr Qolī Beg (from 1736–47, Nādir Shah) in 1735."

- Encyclopaedia of Islam. — Leiden: BRILL, 1986. — vol. 1. — p. 639-640:"The wars between the Ottomans and the Safawids were still to be fought on Armenian soil, and part of the Armenians of Adharbaydjan were later deported as a military security measure to Isfahan and elsewhere. Semi-autonomous seigniories survived, with varying fortunes, in the mountains of Karabagh, to the north of Adharbaydjan, but came to an end in the 18th century."

- Cornell, Svante E. The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict, Uppsala: Department of East European Studies, April 1999, pp. 3–4 Archived 2013-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- C. J. Walker, Armenia: Survival of a Nation, London 1990, p. 40.

- (in Russian) Abbas-gulu Aga Bakikhanov. Golestan-i Iram.

- (in Russian) Mirza Adigezal bey. Karabakh-name, p. 48

- (in Russian) Mirza Jamal Javanshir Karabagi. The History of Karabakh.

- Toumanoff, Cyril. "Manuel de généalogie et de chronologie pour l'histoire de la Caucasie Chrétienne (Arménie-Géorgie-Albanie)." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. London: University of London, Vol. 41, № 2)

- Yesai Hasan Jalalyan. History

- Artsakh from Ancient Time Archived 2006-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Raffi, VII-VIII

- ЦГВИА, ф.52, оп. 2, д. 32, л.1, об. Подлинник

- Artsakh's Principalities Archived 2006-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- "Description of the Karabakh province prepared in 1823 according to the order of the governor in Georgia Yermolov by state advisor Mogilevsky and colonel Yermolov 2nd" ("Opisaniye Karabakhskoy provincii sostavlennoye v 1823 g po rasporyazheniyu glavnoupravlyayushego v Gruzii Yermolova deystvitelnim statskim sovetnikom Mogilevskim i polkovnikom Yermolovim 2-m" in Russian), Tbilisi, 1866.

- Bournoutian, George A. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-E Qarabagh. Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda Publishers, 1994, page 18

- Исмаил-заде, Деляра Ибрагим-кызы. Население городов Закавказского края в XIX – первой половине ХХ века. М., «Наука», 1991

- "Shusha". Brokhaus and Efron Ecyclopaedia, 1899.

- Richard G. Hovannisian. The Republic of Armenia, Volume I: 1918-1919. — London: University of California Press, 1971, pp. 80-81

- Yamskov, A. N. "Ethnic Conflict in the Transcausasus: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh," Special Issue on Ethnic Conflict in the Soviet Union for the Theory and Society 20 (October 1991), pp. 649-650.

- Richard G. Hovannisian. The Republic of Armenia, Volume I: 1918-1919. — London: University of California Press, 1971, pp. 81-82

- Firuz Kazemzadeh, Ph. D. The Struggle For Transcaucasia: 1917–1921. ISBN 0-8305-0076-6

- (in Russian) Michael Smith. Azerbaijan and Russia: Society and State: Traumatic Loss and Azerbaijani National Memory Archived 2011-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "Playing the 'Communal Card': Communal Violence and Human Rights". Human Rights Watch.

- глоссарий Н

- In Alphabetic Order A

- In Alphabetic Order P

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p. 13, Document №8.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p.79, Document №49.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p. 62, Document №38.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p. 73 Document №46.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p.137 Document №84.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, pp.162–164 Document №105.

- "Кавказское слово", 17.06.1919

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, рр. 259, 273, Documents №№172, 180

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, pp.323–326 Document №214.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p.256 Document №376.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p.257 Document №378.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, p.257 Document №380.

- Artsakh in 1918–1920

- "Nagorno-Karabakh Crisis", Public International Law & Policy Group and the New England Center for International Law & Policy

- Tim Potier. Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal ISBN 90-411-1477-7

- Cornell, Svante E. "The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict, Uppsala": Department of East European Studies, April 1999 Archived 2013-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Бюллетень МИД НКР Archived 2005-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Richard G. Hovannisian. The Republic of Armenia, Vol. III: From London to Sèvres, February–August 1920

- Shusha – Encyclopedia, History, Geography and Biography Archived 2007-10-10 at Archive.today

- Большая Советская Энциклопедия. изд.1. т.41 М., 1939, стр. 191, ст. "Нагорно-Карабахская Автономная Область"

- De Waal, Thomas. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, 2003. p. 130. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- Brorers, Laurence (June 2011). "Return, Restitution and Rights: Addressing Legacies of Forced Displacement in the Nagorno Karabakh Conflict". Analyticon. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

Prior to the conflict Azerbaijanis had formed a local majority (98%) in only one major town in NK, Shusha, where they formed a population of 17,000 in 1989.

- Н.Я.Мандельштам. Книга третья. Paris, YMCA-Press, 1987, p. 162-164.

- Нагорный Карабах в 1918–1923 гг.: сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992, Document №297.

- Zare Melik-Shakhnazarov. "Notes of the Karabakh soldier".

- Charlotte Mathilde Louise Hille (2010). State Building and Conflict Resolution in the Caucasus. BRILL. p. 168. ISBN 978-90-04-17901-1.

- "Contested Borders in the Caucasus : Chapter I (2/4)". Poli.vub.ac.be. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- Service, Robert. Stalin: A Biography. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006 p. 204 ISBN 0-674-02258-0

- Тарасов, Станислав. "Станислав Тарасов: Как Сталин "сдал" Карабах Азербайджану".

- Alexei Zverev. "Contested borders in the Caucasus"

- starovoitova.ru/rus/texts/06/books/nas_samoopr

- ПОЛИТИКА: Нагорный Карабах готов к диалогу

- De Waal, Thomas. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, 2003. p. 141. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- De Waal, Thomas. Black garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, 2003. p. 139. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- http://www.memo.ru/hr/hotpoints/karabah/getashen/chapter1.htm

- The conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh region dealt with by the OSCE Minsk Conference Archived 2006-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- United States Library of Congress Country Report on Azerbaijan, "The Issue of Nagorno-Karabakh"

- Trud. 10 points at Politburo scale. February 1, 2001 (in Russian)

- Погромы в Армении: суждения, домыслы и факты. "Экспресс-Хроника", 16.04.1991 г

- Исход азербайджанцев из Армении: миф и реальность. Константин Воеводский

- NISAT. Rokhlin Details Arms Supplied to Armenia Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.noev-kovcheg.ru/article.asp?n=45&a=12%5B%5D

- de Waal, Tom (July 14, 2005). "Chapter 13. June 1992 – September 1993 he was the escalation of the conflict". BBC Russian (in Russian). Archived from the original on March 5, 2006. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- "Defense ministry confirms illegal arms transfer to Armenia". NISAT. Archived 2006-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Armenia armed by Russia for battles with Azerbaijan". The Washington Times April 10, 1997.

- "In Armenian unit, Russian is spoken". The Boston Globe. March 16, 1992.

- General Assembly

- "The Forgotten War". The Wall Street Journal. March 3, 1994.

- "Azerbaijan Throws Raw Recruits Into Battle". The Washington Post. April 21, 1994.

- "Biography: Shamil Basayev". Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism. September 10, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- EurasiaNet Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Chechen fighter's death reveals conflicted feelings in Azerbaijan. May 14, 2002

- Alexey Zverev. Contested borders in the Caucasus.

- Human Rights Watch World Report 1995

- "Permanent mission of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the United Nations – UNICEF Statistics" Archived 2006-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Maria Salinas. FMO Country Guide: Azerbaijan. ReliefWeb (PDF).

- "Conflict Mythology and Azerbaijan". Groong.

- 1912-, Chahin, M. (2001). The kingdom of Armenia : a history (2nd, rev. ed.). Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. p. 107. ISBN 0700714529. OCLC 46908690.

This shows that Urartu was very much in existence [...] down to 594 BC, [...]. It is possible that the last king of Urartu's reigh ended at about the same time or a little earlier. [...] in 590 BC, the Medes marched westwards [towards western Anatolia and Lydia].

CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Levon., Chorbajian (1994). The Caucasian knot : the history & geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh. Donabédian, Patrick., Mutafian, Claude. London: Atlantic Highlands, NJ. p. 53. ISBN 1856492877. OCLC 31970952.

Certain authors estimate that when King Artashes (189–160 BC) brought about the unification of the Kingdom of Great Armenia, Caucasian tribes, probably Albanians, living in Artsakh and Utik were brought in by force. This thesis is said to be based on Strabo, but, in reality, when he describes the conquests Artashes carried out at the expense of the Medes and Iberians – and not the Albanians – he says nothing of Artsakh and Utik, since these provinces were certainly already a part of Armenia.

- 1912-, Chahin, M. (2001). The kingdom of Armenia : a history (2nd, rev. ed.). Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. p. 212. ISBN 0700714529. OCLC 46908690.

The Armenian king, Parthia's ally since the year 53 BC, appeared to submit.

CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Suny (1994), p. 14.

- Theodore Mommsen. The Provinces of the Roman Empire. Chapter IX, p. 68

- Hewsen, Robert H. "The Meliks of Eastern Armenia: A Preliminary Study." Revue des Études Arméniennes. NS: IX, 1972, pp. 255-329.

- Thomas., De Waal (2013). Black garden : Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war (10th-year anniversary ed., rev. and updated ed.). New York: New York University Press. pp. 329–335. ISBN 9780814770825. OCLC 843880838.

- "F-16s Reveal Turkey's Drive to Expand Its Role in the Southern Caucasus". Stratfor. October 8, 2020. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

The presence of the Turkish fighter aircraft ... demonstrate[s] direct military involvement by Turkey that goes far beyond already-established support, such as its provision of Syrian fighters and military equipment to Azerbaijani forces.