Shusha

Shusha (![]() (listen); Azerbaijani: Şuşa; Armenian: Շուշի, romanized: Shushi) is a city and the centre of the Shusha District of Azerbaijan. Situated at an altitude of 1,400–1,800 metres (4,600–5,900 ft) in the Karabakh mountains, Shusha was a mountain recreation resort in the Soviet era.

(listen); Azerbaijani: Şuşa; Armenian: Շուշի, romanized: Shushi) is a city and the centre of the Shusha District of Azerbaijan. Situated at an altitude of 1,400–1,800 metres (4,600–5,900 ft) in the Karabakh mountains, Shusha was a mountain recreation resort in the Soviet era.

Shusha

Şuşa Շուշի • Shushi | |

|---|---|

City | |

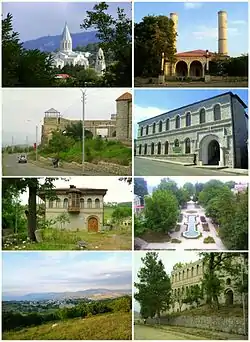

Landmarks of Shusha, from top left: Ghazanchetsots Cathedral • Yukhari Govhar Agha Mosque Shusha fortress • National Gallery History Museum • Central park Shusha skyline • House of Khurshidbanu Natavan | |

Shusha | |

| Coordinates: 39°45.5′N 46°44.9′E | |

| Country | |

| District | Shusha |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bayram Safarov |

| • Special representative | Aydin Karimov[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.5 km2 (2.1 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,800 m (5,900 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 1,400 m (4,600 ft) |

| Population (2015)[2] | |

| • Total | 4,064 |

| Demonym(s) | Shushaly |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| Area code(s) | +994 26 |

| ISO 3166 code | AZ-SUS |

| Vehicle registration | 58 AZ |

| Website | www |

According to some sources, the town of Shusha was founded in 1752 by Panah Ali Khan.[3][4][5] From the mid-18th century to 1822 Shusha was the capital of the Karabakh Khanate. The town became one of the cultural centers of the South Caucasus after the Russian conquest of the Caucasus region in the first half of the 19th century over Qajar Iran.[6] Over time, it became a city and a home to many Azerbaijani intellectuals, poets, writers and especially, musicians (e.g., the ashiks, mugham singers, kobuz players).[7][8]

Other sources suggest that Shusha served as a town and an ancient fortress in the Armenian principality of Varanda during the Middle Ages and through the 18th century.[9][10][11][12] It was one of the two main Armenian cities of the Transcaucasus and the center of a self-governing Armenian principality from medieval times through the 1750s.[13] It also had religious and strategic importance to the Armenians, housing the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral, the church of Kanach Zham, two other churches, a monastic convent, and serving (along with Lachin district to the west) as a land link to Armenia.

Throughout modern history, the city mainly fostered a mixed Armenian–Azerbaijani population. The first available demographic information about the city in 1823 suggest that the city had an Azerbaijani-majority,[14] however, the number of Armenian inhabitants of the city steadily grew over time until the destruction of Armenian quarter of the city in 1920 by Azerbaijani forces, which resulted in the death or expulsion of the Armenian part of the population. After the capture of Shusha in 1992 by Armenian forces during First Nagorno-Karabakh War, its population diminished dramatically again and became exclusively Armenian.

Between May 1992 and November 2020, Shusha was under the de facto control of the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh and administered as part of its Shushi Province. On 8 November 2020, Azerbaijani forces retook the city during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War following a three-day long battle.[15][16]

Etymology

Several historians believe Shusha derives from the New Persian Shīsha ("glass, vessel, bottle, flask").[17][18] According to the Oxford Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names, when Iranian ruler Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar approached the town with his army, he reportedly told to Ibrahim Khalil Khan:[17]

God is pouring stones on thy head. Sit ye not then in thy fortress of glass.

Panahabad ("City of Panah"), Shusha's previous name, was a tribute to Panah Ali Khan, the first ruler of the Karabakh Khanate.[17]

According to Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary the town's name comes from the nearby village Shushikent (called Shosh in Armenian), which literally means "Shusha village"[19] in the Azerbaijani language.[20] Conversely, the Armenian historian Leo considered it more likely that the village Shosh received its name from the fortress, which he considered the older settlement.[21]

According to Armenian sources, Shusha may be derived from the dialectal Armenian word shosh/shush (Armenian: շոշ/շուշ), meaning sprout or young tree, first applied either to the adjacent village Shosh or to Shusha itself. One folk etymology connects it to Russian шоссе, meaning street or highway, although this is unlikely because the names Shusha and Shosh long predate Russian presence in the region.[22] In the first written reference to the settlement in a 15th century Armenian manuscript, the name is rendered as Shushu.[23] Besides the common Armenian name Shushi, the town has historically been referred to in Armenian by various names, including Shoshi/Shushva Berd, Shoshi Sghnakh, Shoshvaghala, which all mean "Shosh/Shushi Fortress"; the settlement was also known simply as Kala/Ghala, meaning fortress. Other historical names include Shikakar Berd ("Red Rock Fortress"), Karaglkhi Sghnakh ("Fortress on a Rock"), or simply Kar ("Rock", compare with adjacent village Karintak, "Under the Rock").[24]

History

Foundation

.jpg.webp)

Shusha as a settlement is first mentioned as "Shushu village" in a 15th century illuminated Armenian Gospel kept on display at Yerevan's Matenadaran (archival number 8211), which is the earliest known artifact from the town. The Gospel was created in Shusha by the calligrapher Ter-Manuel in 1428.[25][26][27][28][23][29]

According to several sources, a settlement called Shusha served as an ancient fortress in the Armenian principality of Varanda, and had traditionally belonged to the Melik-Shahnazarian princely dynasty.[9][10][11][12] The town and fort of Shusha was mentioned as a linchpin of one of East Armenian military districts, called "syghnakhs", which played a key role in the Armenian commander Avan Yuzbashi's campaign against Ottoman forces in the 1720s and 1730s, during the Turkish invasion of the Southern Caucasus.[30]

Kehva Chelebi, an Armenian patriot who maintained correspondence between the meliks of Karabakh and the Russian authorities, in this report of 1725 mentions Shusha as a town and a fort:

… The nearest Armenian stronghold … was Shushi. Shushi is four days' distance from Shemakhi. Armed Armenians under the command of Avan Yuzbashi guard it. After meeting with the Armenian leaders, including the Patriarch, they returned to Derbent via Shemakhi. Rocky mountains surround the town of Shushi. The number of the armed Armenians has not been determined. There are rumors that the Armenians have defeated the Turks in a number of skirmishes in Karabagh …[9]

In his letter of 1769 to the Russian diplomat Count P. Panin, the Georgian king Erekle II documented that "there was an 'ancient' fortress which was conquered, through deceit, by one man from the Muslim Jevanshir tribe."[10] The same information about the 'ancient' fortress is confirmed by the Russian Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov in his letter to Prince Grigory Potemkin.[31][32] Suvorov writes that the Armenian prince Melik Shahnazar of Varanda surrendered his fortress Shushikala to "certain Panah", whom he calls "chief of an unimportant part of nomadic Muslims living near the Karabakh borders."[33] When discussing Karabakh and Shusha in the 18th century, the Russian diplomat and historian S. M. Bronevskiy wrote in his Historical Notes that Shusha fortress was a possession of the Melik-Shahnazarian clan which was given to Panah Ali Khan in return for aid against the other Armenian meliks of Karabakh.[34] Russian historian P. G. Butkov (1775–1857) writes that the "village Shushi" was given to Panah Ali Khan by the Melik-Shahnazarian prince after they entered into an alliance, and that Panah Ali Khan fortified the village.[35][36] Joseph Wolff, during his mission in the Middle East, visited "Shushee, in the province of Carabagh, in Armenia Major".[37]

Azerbaijani and some Armenian 19th-century sources, including Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi, Mirza Adigozal bey, Abbasgulu Bakikhanov, Mirza Yusuf Nersesov and Raffi, attest to the foundation of the town Shusha in 1750–1752 (according to other sources, 1756–1757) by Panah-Ali khan Javanshir (r. 1748–1763), the founder and the first ruler of the Karabakh Khanate (1748–1822), which comprised both Lowland and Highland Karabakh.[38][39] The mid-18th century foundation is supported by Encyclopaedia of Islam,[3] Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary[4] and Great Soviet Encyclopedia.[5]

According to Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi (1773–1853), the author of the Persian-language text History of Karabakh,[40] one of the most significant chronicles on the history of Karabakh in 18th-19th centuries, the Karabakh nobility assembled to discuss the danger of invasion from Iran and told Panah Ali Khan, "We must build among the impassable mountains such an inviolable and inaccessible fort, so that no strong enemy could take it." Melik Shahnazar of Varanda, who was the first of the Armenian meliks (dukes) to accept the suzerainty of Panah Ali Khan and who would remain his loyal supporter, suggested a location for the new fortress. Thus, Panahabad-Shusha was founded.

According to Mirza Jamal Javanshir, before Panah Ali khan constructed the fortress there were no buildings there and it was used as cropland and pasture by the people of the nearby village of Shoshi.[40][41] Panah khan resettled to Shusha the population of Shahbulag and some nearby villages and built strong fortifications.[41]

Another account is presented by Raffi, an Armenian novelist and historian, in his work The Princedoms of Khamsa, who asserts that the place which Shusha was built on was desolate and uninhabited before Panah-Ali Khan's arrival. He states, "[Panah-Ali Khan and Melik-Shahnazar of Varanda] soon completed the construction (1762) [of the fortress] and moved the Armenian population of the nearby village of Shosh (Շոշ), called also Shoshi, or Shushi into the fortress.″[42]

The town was initially named Panahabad, after its founder.[43][44] During the rule of Ibrahim-Khalil khan (r. 1763–1806), the son of Panah Ali khan, the town received its present name from a nearby village called Shushikent (literally translating to "village of Shushi" from Azerbaijani) or Shosh.[39]

Conflict with the Qajars

Although Panah Ali khan has been in conflict with Nader Shah, the new ruler of Persia, Adil Shah, issued a firman (decree) recognizing Panah Ali as the Khan of Karabakh.[45] Less than a year after Shusha was founded, the Karabakh Khanate was attacked by Mohammad Hassan Khan Qajar, one of the major claimants to the Iranian throne. During the Safavid Empire Karabakh was for almost two centuries ruled by Ziyad-oglu family of the clan of Qajars (of Turkic origin),[46] and therefore, Muhammed Hassan khan considered Karabakh his hereditary estate.[41][44][47][48]

Muhammed Hassan khan besieged Shusha (Panahabad at that time) but soon had to retreat, because of the attack on his territory by his major opponent to the Iranian throne, Karim Khan Zand. His retreat was so hasty that he even left his cannons under the walls of Shusha fortress. Panah Ali khan counterattacked the retreating troops of Mohammad Hassan khan and even briefly took Ardabil across the Aras River.

In 1756 (or 1759), Shusha and the Karabakh Khanate underwent a new attack from Fath-Ali Khan Afshar, ruler of Urmia. With his 30,000 strong army, Fatali khan also managed to gain support from the meliks (feudal vassals) of Jraberd and Talish (Gulistan), however, melik Shahnazar of Varanda continued to support Panah Ali khan. Siege of Shusha lasted for six months and Fatali khan eventually had to retreat.

When Karīm Khan Zand took control of much of Iran, he forced Panāh Khan to come to Shiraz (Capital), where he died as a hostage.[49] Panah-Ali Khan's son Ibrahim-Khalil Khan was sent back to Karabakh as governor.[50] Under him Karabakh khanate became one of the strongest state formations and Shusha grew. According to travellers who visited Shusha at the end of 18th-early 19th centuries the town had about 2,000 houses and approximately 10,000 population.

In summer 1795, Shusha was subjected to a major attack by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, son of Mohammad Hassan khan who attacked Shusha in 1752. Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar's goal was to end with the feudal fragmentation and to restore the old Safavid State in Iran. By early 1795, he had already secured mainland Iran and was directly afterwards poised to bring the entire Caucasus region back within the Iranian domains.[51] For this purpose he also wanted to proclaim himself Shah (king) of Iran. However, according to the Safavid tradition, the shah had to take control over the whole of South Caucasus and Dagestan before his coronation. Therefore, Karabakh Khanate and its fortified capital Shusha, were the first and major obstacle to achieve these ends.

Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar besieged Shusha with the centre part of a 70,000-strong army, after having crossed the Aras River.[52] The right and left wings were sent to resubjugate Shirvan-Dagestan and Erivan respectively. Agha Mohammad Khan himself led the centre part of the main army, besieging Shusha between 8 July and 9 August 1795.[53] Ibrahim Khalil khan mobilized the population for a long-term defense. The number of militia in Shusha reached 15,000. Women fought together with men. The Armenian population of Karabakh also actively participated in this struggle against the Iranians and fought side by side with the Muslim population, jointly organizing ambushes in the mountains and forests.

The siege lasted for 33 days. Not being able to capture Shusha, Agha Mohammad Khan, for now, ceased the siege,[54] and advanced to Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi), which despite desperate resistance was occupied and exposed to unprecedented destruction. The Khan of Karabakh, Ibrahim Khan, eventually surrendered to Mohammad Khan after discussions, including the paying of regular tribute and to surrender hostages, though the Qajar forces were still denied entrance to Shusha.[54] Since the main objective was Georgia, Mohammad Khan was willing to have Karabakh secured by this agreement for now, for he and his army subsequently moved further.[54]

In 1797, Agha Mohammad Shah Qajar, having successfully re-subjugated Georgia and the wider Caucasus, and had by that time already managed to declare himself shah conform the same traditions Nader Shah had done as well in the nearby Mughan plain,[55] (nowadays shared between the Republic of Azerbaijan and Iran) decided to carry out a second attack on Karabakh.

Trying to avenge the previous humiliating defeat Qajar devastated the surrounding villages near Shusha. The population could not recover from the previous 1795 attack and also suffered from serious drought which lasted for three years. The artillery of the enemy also caused serious losses amongst the city defenders. Thus, in 1797 Agha Mohammad Shah succeeded in seizing Shusha and Ibrahim Khalil khan had to flee to Dagestan.

However, several days after the seizure of Shusha, Agha Mohammad Khan was killed in mysterious circumstances by his bodyguards in the town.[56] Ibrahim Khalil khan returned to Shusha and ordered that the shah's body be honourably buried until further instructions from the nephew and heir of Agha Mohammad Shah, Baba Khan, who soon assumed the title of Fath-Alī Shah.[57] Ibrahim khan, in order to maintain peaceful relations with Tehran and retain his position as the khan of Karabakh, gave his daughter Agha Begom, known as Aghabaji, as one of the wives of the new shah.[57]

Shusha within the Russian Empire

From the early 19th century, Russian ambitions in the Caucasus to increase its territories at the expense of neighbouring Qajar Iran and Ottoman Turkey began to rise. Following the annexation of Georgia in 1801, some of the khanates accepted Russian protectorate in the immediate years afterwards. In 1804, the Russian general Pavel Tsitsianov directly invaded Qajar Iran initiating the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813. Amidst the war, in 1805, an agreement was made between the Karabakh Khanate and the Russian Empire on the transfer of the Karabakh Khanate to Russia amidst the war, but was not fully realized, as both parties were still at war and the Russians were unable to consolidate any effective possession over Karabakh.

The Russian Empire consolidated its power in the Karabakh Khanate following the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, when Iran was forced to recognize the belonging of the Karabakh Khanate,[58] along most of the other khanates they possessed in the Caucasus, to Russia, comprising present-day Dagestan and most of the Azerbaijan Republic, while officially ceding Georgia as well, thus irrevocably losing the greater part of its Caucasian territories.[59] Absolute consolidation of Russian power over Karabakh and the recently conquered parts of the Caucasus from Iran were confirmed with the outcome of the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828 and the ensuing Treaty of Turkmenchay of 1828.[60]

During the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828, the citadel at Shusha held out for several months and never fell. After this Shusha ceased to be a capital of a khanate, which was dissolved in 1822, and instead became an administrative capital of first the Karabakh province (1822–1840), following Persia's ceding to Russia, and then of the Shusha district (uyezd) of the Elisabethpol Governorate (1840–1923). Shusha grew and developed, with successive waves of migrants moving to the city, particularly Armenians, who formed a demographic majority in the surrounding highlands.[61][14][62]

Beginning from the 1830s the town was divided into two parts: Turkic-speaking Muslims lived in the eastern lower quarters, while Armenian Christians settled in the relatively new western upper quarters of the town. The Muslim part of the town was divided into seventeen quarters. Each quarter had its own mosque, Turkish bath, water-spring and also a quarter representative, who would be elected among the elders (aksakals), and who would function as a sort of head of the present-day municipality. The Armenian part of the town consisted of 12 quarters, five churches, town and district school and girls' seminary.

The population of the town primarily dealt with trade, horse-breeding, carpet-weaving and wine and vodka production. Shusha was also the biggest centre of silk production in the Caucasus. Most of the Muslim population of the town and of Karabakh, in general, was engaged in sheep and horse-breeding and therefore, had a semi-nomadic lifestyle, spending wintertime in lowland Karabakh in wintering pastures and spring and summer in summering pastures in Shusha and other mountainous parts.

In the 19th century, Shusha was one of the great cities of the Caucasus, larger and more prosperous than either Baku or Yerevan.[63] Standing in the middle of a net of caravan routes, it had ten caravanserais.[63] It was well known for its silk trade, its paved roads, brightly coloured carpets, big stone houses, and fine-bred horses.[63] In 1824, George Keppel, the Earl of Albemarle, passed through the city.[63] He found two thousand houses in the town, with three-quarters of the inhabitants Azerbaijanis and one-quarter Armenian.[64] He furthermore noted regarding the town;[63]

(...) The language is a dialect of the Turkish; but its inhabitants, with the exception of the Armenians, generally read and write Persian. The trade is carried on principally by the Armenians, between the towns of Sheki, Nakshevan, Khoi and Tabriz."

Early 20th century

The beginning of the 20th century marked the first Armenian-Tartar clashes throughout Azerbaijan. This new phenomenon had two reasons. First, it was the result of increased tensions between the local Muslim population and Armenians, whose numbers increased throughout the 19th century as a result of Russian resettlement policies. Second, by the beginning of the 20th-century peoples of the Caucasus, similar to other non-Russian peoples in the periphery of the Russian Empire began to seek cultural and territorial autonomy. That is why, at the beginning of the 20th century in Russia itself was a period of bourgeois and Bolshevik revolutions, in the peripheries these movements have acquired a character of the national liberation movement.

The initial clashes between ethnic Armenians and Azerbaijanis took place in Baku in February 1905. Soon, the conflict spilled over to other parts of the Caucasus, and on August 5, 1905, first conflict between the Armenian and Azerbaijani inhabitants of Shusha took place. As a result of the mutual pogroms and killings, hundreds of people died and more than 200 houses were burned.[65]

After World War I and subsequent collapse of the Russian Empire, Karabakh was claimed by Azerbaijan to be part of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, a decision hotly disputed by neighbouring Armenia and by Karabakh's Armenian population, which claimed Karabakh as part of the First Republic of Armenia. After the defeat of Ottoman Empire in the World War I, Armenian forces under Andranik Ozanian defeated Azerbaijani forces under Khosrov bey Sultanov in Abdallyar, and began heading down the Lachin corridor towards Shusha. Shortly before Andranik could arrive, British troops under General W. M. Thomson encouraged him to retreat, as Armenian military activity may have an adverse effect on the region's status to be decided at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.[66] Trusting Thomson, Andranik left, and the British troops occupied Karabakh. The British command provisionally affirmed Sultanov (appointed by the Azerbaijani government) as the governor-general of Karabakh and Zangezur, pending final decision by the Paris Peace Conference.[67][68]

To make the local Armenians surrender to the Azerbaijani rule Sultanov employed most severe measures against them such as terror, blockade and famine.[69][70][71]

The ethnic conflict began to erupt in the region. Оn 5 June 1919, 600 Armenian inhabitants of the villages surrounding Shusha were killed by Azerbaijani and Kurdish irregulars. Sultanov stated that those irregulars were not under his control.[70] In August 1919, the Karabakh National Council was forced to enter into a provisional treaty agreement with the Azerbaijani government, recognizing the authority of the Azerbaijan government until the issue of the mountainous part of Karabakh would be settled at the Paris Peace Conference. Despite signing the Agreement, the Azerbaijani government continuously violated the terms of the treaty, employing even more severe measures against the Armenian population.[72][73] Governor-General Sultanov accumulated troops in the region and on 19 February 1920 issued an ultimatum to the Armenians to accept unconditional unification with Azerbaijan, then massacred the population of several Armenian villages including Khankendi.[73] A minority of Karabagh National Council representatives gathered in Shusha to accept Sultanov's demands, while the rest met in nearby Shushikend to reject the ultimatum.[73] The strife culminated in an Armenian uprising,[74][75][76] which was suppressed by the Azerbaijani army. In late March 1920, the Armenian half of the police forces was reported by a British journalist to have murdered the Azerbaijani half during the latter's traditional Novruz Bayram holiday celebrations. The Armenian surprise attack was organised and coordinated by the forces of the Armenian Republic.[77][78] Azerbaijani outrage for this surprise attack ultimately led to the massacre of March 1920, in which between 500[79] to 20,000[80] of the Armenian population of Shusha was killed, and many forced to flee.

According to the description of an Azerbaijani communist Ojahkuli Musaev:

... the ruthless destruction of defenceless women, children, old women, old men, etc has begun. Armenians were exposed to mass slaughter. ... beautiful Armenian girls were raped, then shot. ... By the order of ... Khosrov-bek Sultanov; the pogroms proceeded for more than six days. Houses in the Armenian part have been partially demolished, plundered and reduced all to ashes, everyone led away women to submit to the wishes of executioner musavatists. During these historically artful forms of punishment, Khosrov-bek Sultanov, spoke about holy war (jihad) in his speeches to the Moslems, and called on them to finally finish the Armenians of the city of Shusha, not sparing women, children, etc.[81]

Nadezhda Mandelstam wrote about Shusha in the 1920s, "in this town, which formerly of course was healthy and with every amenity, the picture of catastrophe and massacres was terribly visual. ... They say after the massacres all the wells were full of dead bodies. ... We didn't see anyone in the streets on the mountain. Only in downtown—in the market-square, there were a lot of people, but there wasn't any Armenian among them; all were Muslims".[82]

Soviet era

In 1920, the Bolshevik 11th Red Army invaded Azerbaijan and then Armenia and put an end to the national de facto governments that existed in those two countries. Thereafter, the conflict for the control of Karabakh entered the diplomatic sphere. To attract Armenian public support, the Bolsheviks promised to resolve the issue of the disputed territories, including Karabakh, in favour of Armenia. However, on July 5, 1921, the Kavbiuro of the Communist Party adopted the following decision regarding the future status of Karabakh: "Proceeding from the necessity of national peace among Muslims and Armenians and of the economic ties between upper (mountainous) and lower Karabakh, of its permanent ties with Azerbaijan, mountainous Karabakh is to remain within AzSSR, receiving wide regional autonomy with the administrative centre in Shusha, which is to be included in the autonomous region." As a result, the Mountainous Karabakh Autonomous Region was established within the Azerbaijan SSR in 1923. Few years later, Stepanakert, named after the Armenian communist leader Stepan Shaumyan, became the new regional capital of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast and soon became its largest town.

The decision favoring Azerbaijan was due to Stalin, who knew that by including the disputed and by then majority Armenian-populated region within the boundaries of Azerbaijan, it would ensure Moscow's position as power broker.[83][84]

The town remained half-ruined until the 1960s when the town began to gradually revive due to its recreational potential. In 1977 the Shusha State Historical and Architectural Reserve was established and the town became one of the major resort-towns in the former USSR.

The Armenian quarter continued to lie in ruins until the beginning of the 1960s. In 1961, Baku's communist leadership finally passed a decision to clear away much of the ruins, even though many old buildings still could have been renovated. Three Armenian and one Russian church were demolished and the Armenian part of the town was built up with plain buildings typical of the Khrushchev era.

1988–1994 Nagorno-Karabakh War

With the start of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1988 Shusha became the most important Azerbaijani stronghold in Karabakh, from where Azerbaijani forces constantly shelled the capital Stepanakert. On May 9, 1992, the town was captured by Armenian forces and the Azerbaijani population fled.[85] The city was looted and burnt by Armenians. According to Azerbaijani sources, 193 Azerbaijani civilians were massacred.[86] As of 2002, ten years later after the city's capture by the Armenian forces, some 80% of the town was in ruins.[87]

After the end of the war, the town was repopulated by Armenians, mostly refugees from Azerbaijan and other parts of Karabakh, as well as members of the Armenian diaspora. While the population of the town is barely half of the pre-war number, and the demographic of the town has changed from mostly Azerbaijani to completely Armenian, a slow recovery can be seen. The Goris-Stepanakert Highway passes through the town and is a transit and tourist destination for many. There are some hotels in the city, and reconstruction work continues, in particular, the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral recently finished going through the restoration process.

After the war, a T-72 tank commanded by the Karabakhi Armenian Gagik Avsharian was placed as a memorial. The tank had been hit during the town's capture, killing the driver and gun operator, but Avsharian jumped free from the hatch. The tank was restored and its number, 442, repainted in white on the side.[88]

2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

.jpg.webp)

During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Armenia accused the Azerbaijani army of shelling civilian areas and the city's Ghazanchetsots Cathedral. Three journalists were wounded while they were inside the cathedral to film the destruction of a previous shelling on the same day.[89] Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence has denied the shelling of the cathedral by stating that "destruction of the church in Shusha has nothing to do with the activities of the Army of Azerbaijan"[90] The House of Culture was also badly damaged in the fighting.[91]

On November 8, 2020, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev announced that the Azerbaijani army took control of the city of Shusha.[92] The next day, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence released a video from the city, confirming full Azerbaijani control.[15] On the same day, Artsakh authorities confirmed that they had lost control of Shusha.[93] A ceasefire signed two days later reaffirmed Azerbaijan's gains, resulting in the city staying under its control. The Armenian government and the Armenian Apostolic Church subsequently claimed that Azerbaijani soldiers had vandalised Armenian churches and cultural landmarks, including Ghazanchetsots Cathedral[94][95] and Kanach Zham,[96] while the Azerbaijani officials stated that the Mamayi Mosque and a nearby fountain was vandalised by the Armenians forces.[97]

Culture

%252C_Shusha%252C_1915.jpg.webp)

Shusha contains both Armenian and Azerbaijani cultural monuments, while the surrounding territories also include many ancient Armenian villages.[98]

The city is one of the leading centres of the Azerbaijani culture,[99] and was declared the cultural capital of Azerbaijani culture on January 2021.[100] It is often associated with the musical traditions of Azerbaijani people. Shusha is home to one of the leading schools of mugham, traditional Azerbaijani genre of vocal and instrumental arts. Shusha is particularly renowned for this art.[101]

Shusha is also a historical Armenian religious and cultural center.[102][103] The Armenian population of the town historically had four main churches, each named after the place of origin of the Armenian inhabitants: Ghazanchetsots (after Qazançı; officially named Holy Savior Cathedral), Aguletsos Holy Mother of God Church (after Agulis), Meghretsots Holy Mother of God Church (after Meghri), and Gharabakhtsots (after the region of Karabakh; the church is better known as Kanach Zham).[104] Shusha was also home to a monastery complex called Kusanats Vank ("Virgins' Monastery") or Anapat Kusanats ("Virgins' Hermitage")․[104] In 1989, Ghazanchetsots Cathedral was made the seat of the newly reestablished Diocese of Artsakh of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[105]

Shusha is also well known for sileh rugs, floor coverings from the South Caucasus. Those from the Caucasus may have been woven in the vicinity of Shusha. A similar Eastern Anatolian type usually shows a different range of colours.[106]

In November 2020, the organizers of the Turkvision Song Contest stated that they were exploring the possibility of holding the contest's 2021 version in Shusha,[107] and in January 2021, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Culture started preparatory activities on the Khari Bulbul Festival and Days of the Poetry of Vagif.[108]

Museums

During the Soviet period, Shusha was home to museums such as the Shusha Museum of History, the house museum of Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, the house museum of the Azerbaijani singer Bulbul, and the Shusha Carpet Museum.[109] The Azerbaijan State Museum of History of Karabakh was founded in Shusha in 1991 shortly before the outbreak of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War.

While the city was under Armenian control, a number of museums were operated there: the State Museum of Fine Arts, G. A. Gabrielyants State Geological Museum, the Shushi History Museum, the Shushi Carpet Museum and the Shushi Art Gallery.[110]

The Shushi History Museum is located in a 19th-century mansion, in the centre of the historical quarter, and had a collection of artefacts related to Shusha from ancient to modern times.[110] The collection of the museum contains many ethnographic materials, including the goods of local masters. The museum contains household articles, photographs, and reproductions illustrating life of 19th-century inhabitants of Shusha. There are also sections dedicated to the 1920 Shusha Massacre and the capture of Shusha by Armenian forces in 1992. The G. A. Gabrielyants State Geological Museum was opened in Shusha in 2014, named after and created by Armenian geologist Grigori Gabrielyants. It contains 480 samples of ore and fossil from 47 countries of the world.[110]

Except for the rugs kept at the Shushi Carpet Museum, which were removed, the collections of the museums in Shusha were left behind and remained in the city after the capture of Shusha by Azerbaijani forces in 2020.[110]

Demographics

| Year | Armenians | Azerbaijanis | Others | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1823[14] | |||||||

| 1830[61] | |||||||

| 1851[111] | |||||||

| 1886[112] | |||||||

| 1897[113] | |||||||

| 1904[114] | |||||||

| 1916[115] | |||||||

| March 1920: Massacre and expulsion of Armenian population by Azerbaijan | |||||||

| 1926[112] | |||||||

| 1939[116] | |||||||

| 1959[117] | |||||||

| 1970[118] | |||||||

| 1979[119] | |||||||

| September 1988: Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: Expulsion of Armenian population[120] | |||||||

| 1989[121] | |||||||

| May 1992: Capture by Armenian forces. Expulsion of Azerbaijani population | |||||||

| 2005[123] | |||||||

| 2009[124] | |||||||

| 2015[2] | |||||||

According to first Russian-held census of 1823 conducted by Russian officials Yermolov and Mogilevsky, in Shusha were 1,111 (72.5%) Muslim families and 421 (27.5%) Armenian families.[14] Seven years later, according to 1830 data, the number of Muslim families in Shusha decreased to 963 (55.8%) and the number of Armenian families increased to 762 (44.2%).[61][125]

George Keppel, the Earl of Albemarle, who wrote on his way back to England from India arrived in Karabakh from Persia in 1824, wrote that “Sheesha contains two thousand houses: three parts of the inhabitants are Tartars, and the remainder Armenians”.[126]

A survey prepared by the Russian imperial authorities in 1823 shows that all Armenians of Karabakh compactly resided in its highland portion, i.e. on the territory of the five traditional Armenian principalities, and constituted an absolute demographic majority on those lands. The survey's more than 260 pages recorded that the five districts had 57 Armenian villages and seven Tatar villages.[62][127]

The 19th century also brought some alterations to the ethnic demographics of the region. Following the invasions from Iran (Persia), Russo-Persian wars and subjection of Karabakh khanate to Russia, many Muslim families emigrated to Iran while many Armenians moved to Shusha.[61]

In 1851, the population of Shusha was 15,194 people,[111] in 1886 – 30,000,[128] in 1910 – 39,413[129] and in 1916 – 43,869, of which 23,396 (53%) were Armenians, and 19,121 (44%) were Tatars (Azerbaijanis).[115]

By the end of the 1880s, the percentage of Muslim population living in the Shusha district (part of earlier Karabakh province) decreased even further and constituted only 41.5%, while the percentage of the Armenian population living in the same district increased to 58.2% in 1886.

By the second half of the 19th century, Shusha had become the largest town in the Karabakh region. However, after the pogrom against the Armenian population in 1920 and the burning of the town, Shusha was reduced to a small provincial town of some 10,000 people. Armenians did not begin to return until after World War II. It was not until the 1960s that the Armenian quarter began to be rebuilt.

According to the last population census in 1989, the town of Shusha had a population of 17,000 and Shusha district had a population of 23,000. 91.7% of the population of Shusha district and 98% of Shusha town were Azerbaijani.[122]

Following the capture of Shusha by the Armenian forces in 1992, the Azerbaijani population of the town, consisting of 15,000 people,[130] was killed and expulsed.[86] Before the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, the population consisted of over 4,000 Armenians,[2] mainly refugees from Baku,[131][132] and other parts of Karabakh and Azerbaijan.[133][134] As a result of the first war, no Azerbaijanis live in Shusha today, although Azerbaijani authorities plan to repopulate it with Azerbaijani displaced persons who fled Shusha during the first war.[122][135][136] Shusha's Armenian population fled shortly before the city was captured by Azerbaijani forces during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War.[137]

Economy and tourism

While the town was under Armenian control, there were efforts to revive the city's economy by the Shushi Revival Fund,[138] the ArmeniaFund, and by the government of Artsakh. Investment in tourism led to the opening of the Shoushi Hotel, the Avan Shushi Plaza Hotel and the Shushi Grand Hotel. A tourist information office was also opened,[139] the first in the Republic of Artsakh. The two remaining Armenian churches (Ghazanchetsots and Kanach Zham) were renovated, and schools, museums and the Naregatsi Arts Institute have opened.

Notable natives

- Ibrahim Khalil Khan (1732-1806), Azerbaijani khan of the Karabakh Khanate.

- Gasim bey Zakir (1784–1857), Azerbaijani poet.

- Jafargulu agha Javanshir (1787–1867), Azerbaijani poet and major general of the Imperial Russian Army.

- Abbasqoli Mo'tamad-dawla Javanshir (1804-1862), Azerbaijani statesman and first minister of justice of Iran.

- Karbalayi Safikhan Karabakhi (1820–1879), Azerbaijani architect and one of the representatives of Karabakh architecture schools.

- Ivan Davidovich Lazarev (1820–1879), Armenian lieutenant-general of the Imperial Russian Army.

- Usta Gambar Karabakhi (1830–1905), Azerbaijani ornamentalist painter.

- Khurshidbanu Natavan (1832–1897), one of the best lyrical poets of Azerbaijan.

- Sadigjan (1846–1902), Azerbaijani musician.

- Muratsan (1854–1908), Armenian writer and novelist.

- Karim bey Mehmandarov (1854-1929), Azerbaijani physician, founder of the Russian-Azerbaijani Shusha girls school.

- Amanullah Mirza Qajar (1857–1937), prince of Iran's Qajar dynasty. Major general in the Russian Empire and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, later military figure and politician in Iran.

- Leo (1860–1932), Armenian historian.

- Stepan Aghajanian (1863–1940), Armenian painter.

- Hambardzum Arakelian (1865–1918), Armenian journalist and public activist.

- Alexander Atabekian (1868–1933), prominent Armenian anarchist.

- Ahmet Ağaoğlu (1869–1939), Azerbaijani politician and journalist.

- Abdurrahim bey Hagverdiyev (1870–1933), Azerbaijani playwright, stage director, politician and public figure.

- Feyzullah Mirza Qajar (1872–1920), prince of Iran's Qajar dynasty. Major general in the Russian Empire and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, later military figure and politician in Iran.

- Suleyman Sani Akhundov (1875–1939), Azerbaijani playwright and journalist.

- Vartan Sarkisov (1875–1955), Soviet-Armenian architect.

- Freidun Aghalyan (1876–1944), Armenian architect.

- Tuman Tumanian (1879–1906), Armenian liberation movement leader.

- Zulfugar Hajibeyov (1884–1950), Soviet-Azerbaijani composer.

- Ahmed Agdamski (1884–1954), Soviet-Azerbaijani opera singer.

- Arsen Terteryan (1882–1953), Soviet-Armenian scientist.

- Artashes Babalian (1886–1959), a politician of the First Republic of Armenia.

- Sahak Ter-Gabrielyan (1886–1937), Soviet-Armenian statesman.

- Hayk Gyulikekhvyan (1886–1951), Armenian literary critic.

- Ashot Hovhannisyan (1887–1972), Soviet-Armenian statesman and historian.

- Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli (1887–1943), Soviet-Azerbaijani and writer.

- Nariman bey Narimanbeyov (1889–1937), Azerbaijani lawyer and statesman.

- Mikael Arutchian (1897–1961), Soviet-Armenian painter.

- Bulbul (1897–1961), Soviet-Azerbaijani opera tenor and folk music performer, father of Polad Bülbüloğlu, Azerbaijani singer, actor and diplomat.

- Ivan Tevosian (1902–1958), Soviet-Armenian statesman.

- Khan Shushinski (1901–1979), was an Azerbaijani khananda folk singer.

- Süreyya Ağaoğlu (1903–1989), Turkish Azerbaijani origin writer, jurist, and the first female lawyer in Turkish history.

- Ivan Knunyants (1906–1990), Soviet-Armenian chemist.

- Latif Karimov (1906–1991), Azerbaijani carpet designer known for his contributions to a variety of artistic fields, as well as for a number of books classifying and describing various designs of Azerbaijani rugs.

- Gevork Kotiantz (1909–1996), Soviet-Armenian painter.

- Shamsi Badalbeyli (1911–1987), Soviet-Azerbaijani actor and theatre director.

- Nelson Stepanyan (1913–1944), Soviet-Armenian pilot and Lieutenant–Colonel of the Red Army.

- Barat Shakinskaya (1914–1999), Soviet-Azerbaijani actress.

- Gurgen Boryan (1915–1971), Soviet-Armenian poet and playwright.

- Soltan Hajibeyov (1919–1974), Soviet-Azerbaijani composer.

- Seyran Ohanyan (born 1962), Armenian politician and military commander.

References

Notes

- "Айдын Керимов назначен спецпредставителем Президента Азербайджана в Шушинском районе - Распоряжение". Trend News Agency (in Russian). 27 January 2021. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Table 1.6 NKR urban and rural settlements grouping according to de jure population number" (PDF). stat-nkr.am. Population Census 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2020.

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume 4, Parts 69–78, Brill, 1954, p. 573.

- Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (1890–1907). Shusha. St Petersburg. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia (1969–1978). Shusha. Moscow. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine pp 728 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- "Azerbaijan" (2007) In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 3, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-44296 Archived 2006-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Suny, Ronald (1996). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. DIANE Publishing. p. 108. ISBN 0788128132.

- Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626–1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, page 133, Kekhva Chelebi's Report to the Collegium of [Russian] Foreign Affairs (17 December 1725)

- Цагарели А. А. Грамота и гругие исторические документы XVIII столетия, относяшиеся к Грузии, Том 1. СПб 1891, ц. 434–435. This book is available online from Google Books.

- Армяно-русские отношения в XVIII веке. Т. IV. С. 212, as cited in О. Р. Айрапетов, Мирослав Йованович, М. А. Колеров, Брюс Меннинг, Пол Чейсти. Русский Сборник Исследования По Истории России. p. 13. Citation: «Совет мелика Адама, мелика Овсепа и мелика Есаи был един, но среди них раскольничал мелик Шахназар, который был мужем хитрым, маловерным и негодным к добрым делам, коварным и предающим братьев. В Карабах приходит некое племя Джваншир, словно бездомные скитальцы на земле, чинящее разбой и кочующее в шатрах, главарю которых имя было Панах-хан. Коварный во злых делах мелик Шахназар призвал его себе в помощь, по собственной воле подчинился ему и передал свою крепость». "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Կռունկ Հայոց աշխարհին. 1863. № 8, էջ 622 (Krunk Hayots Ashkharhi. 1863. № 8. С. 622), as cited in О. Р. Айрапетов, Мирослав Йованович, М. А. Колеров, Брюс Меннинг, Пол Чейсти. Русский Сборник Исследования По Истории России. p. 14. Citation: «Шахназар, мелик Варанды, страшась союза между Меликом Чараберда Адамом и Меликом Гюлистана Овсепом, сам подружился с Панах-ханом, отдал ему свое поселение Шушинскую крепость, а также свою дочь в жены». "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Crossroads and Conflict: Security and Foreign Policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia, By Gary K. Bertsch, Scott A. Jones, Cassady B. Craft, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0-415-92274-7, p. 297

- "Description of the Karabakh province prepared in 1823 according to the order of the governor in Georgia Yermolov by state advisor Mogilevsky and colonel Yermolov 2nd" ("Opisaniye Karabakhskoy provincii sostavlennoye v 1823 g po rasporyazheniyu glavnoupravlyayushego v Gruzii Yermolova deystvitelnim statskim sovetnikom Mogilevskim i polkovnikom Yermolovim 2-m" in Russian), Tbilisi, 1866.

- "Azerbaijan, Armenia and Russia sign peace deal over Nagorno-Karabakh". edition.cnn.com. CNN. 10 November 2020.

- "Президент Арцаха прокомментировал мир с Азербайджаном". www.mk.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- Everett-Heath 2018.

- Chkeidze 2001, pp. 486-490.

- Şuşakənd (PDF). Baku: Encyclopedia of Azerbaijani toponyms. 2007. p. 304. ISBN 978-9952-34-156-0.

- "Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary".

- Mkrtchyan, Shahen (1980). "City of Shushi (Շուշի քաղաքը)". Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի պատմա-ճարտարապետական հուշարձանները (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan publishing house. p. 146.

- Dalalyan, Tork. "Շուշի տեղանունը, ծագումն ու ստուգաբանությունը [լեզվաբան-բանագետ Տորք Դալալյանն է պարզաբանում]". 9 November 2020. vnews.am. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Khachikyan L. S., (1955), Memorial records in Armenian manuscripts of 15 c., Part I (1401–1450) Archived 2014-12-13 at the Wayback Machine, Publish. of Academy of Sciences of ArmSSR, p. 384. (in Armenian)

- "Shushi". Dictionary of toponymy of Armenia and adjacent territories (in Armenian). 4. Yerevan: YSU Publishing House. 1986. p. 161.

- Boris Baratov. A Journey to Karabakh. Moscow, 1998, pp. 32–33

- Hravard Hakobian. Miniatures of Artsakh and Utik 13th–14th centuries. p. 25, Yerevan, 1989

- Епископ Макар Бархутарянц, История Албании, том 1, Вагаршапат, 1902, с. 384 (на арм. яз); Bishop Makar Barkhudariants. History of Aghvank. Volume 1, Vagharshapat, 1902, p. 384

- Ulubabyan B. A. (1972), The Principality of Lower Khachen from the 14th to the 15th centuries. Archived 2013-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, Historico-philological journal of Academy of Sciences of ArmSSR № 11. pp. 95–108, p. 105. (in Armenian)

- Barkhudarian, Bishop Makar (1895). "City of Shushi (Շուշի քաղաք)". Artsakh (PDF) (in Armenian). Baku: Aror publishing house. p. 137.

- Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, Armenian Military Activities in Karabakh and Ghapan, pages 402-413

- А. В. Суворов и русско-армянские отношения в 1770-1780-х годах. Ереван. Айастан. 1981

- Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, page 134, 269.

- Alexander Suvorov's text says: "Мелик Шах-Назар может собрать войска близ 1000 человек; сей предатель своего отечества призвал Панахана, бывшего прежде начальником не знатной части кочующих магометан близ границ карабагских, отдал ему в руки свой крепкий замок Шушикала и учинился ему с его сигнагом покорным."А. В. Суворов и русско-армянские отношения в 1770-1780-х годах. Ереван. Айастан. 1981, letter to G. Potemkin of 15 February 1780. Web reference is here: http://www.vostlit.info/Texts/Dokumenty/Kavkaz/XVIII/1760-1780/Suvorov_arm/text.phtml?id=3016 Archived 2009-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- S.M.Bronesvskiy. Historical Notes... Archived 2009-02-12 at the Wayback Machine St. Petersburg. 1996. Исторические выписки о сношениях России с Персиею, Грузиею и вообще с горскими народами, в Кавказе обитающими, со времён Ивана Васильевича доныне». СПб. 1996, секция "Карабаг". Bronesvskiy writes: "Мелик Шахназор призвал к себе на помощь владетеля кочующаго чавонширскаго народа Фона хана и здал ему крепость Шуши."

- Материалы для новой истории Кавказа с 1722 по 1803 год П. Г. Буткова. СПб. 1869, ПРИЛОЖЕНИЕ М. к стр. 236 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Also see Walker Christopher "The Armenian Presence in Mountainous Karabakh" in "Transcaucasian Boundaries" (SOAS/GRC Geopolitics) edited by John Wright, Richard Schofield, Suzanne Goldenberg, 1995 p. 93 "South of Khachen lay the small territory of Varanda, originally part of its southern neighbour, Dizak, and only given a separate identity in the early sixteenth century. The ruling family, confirmed in that capacity by Shah Abbas I, was that of the Melik Shahnazarians. In the territory of Varanda lies the modern town of Shushi (or Shusha)"

- Travels and Adventures of the Rev. Joseph Wolff, D.D., LL.D.: Late Missionary to the Jews and Muhammadans in Persia, Bokhara, Cashmeer, Etc., Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 226, also in the first publication -

- "Azerbaijan - History, People, & Facts". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Hewsen, Robert H., Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 155.

- Bournoutian George A. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-E Qarabagh. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1994, p. 72. The original text by Mirza Jamal Javanshir calls the village "Shoshi."

- (in Russian) Mirza Jamal Javanshir Karabagi. The History of Karabakh Archived 2007-01-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- Raffi. The Princedoms of Khamsa Archived 2009-11-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Great Soviet Encyclopedia, "Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast", 3rd edition, Moscow, 1970". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- "АББАС-КУЛИ-АГА БАКИХАНОВ->ГЮЛИСТАН-И ИРАМ->ПЕРИОД V". vostlit.info. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007.

- Mirza Adigozel-bek, Karabakh-name (1845), Baku, 1950, p. 54

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Qajar Dynasty, Online Academic Edition, 2007.

- "МИРЗА АДИГЕЗАЛЬ-БЕК->КАРАБАГ-НАМЕ->ГЛАВЫ 1-6". www.vostlit.info. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010.

- Encyclopedia Iranica. C. Edmund Bosworth. Ganja. Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Bournoutian, George. "EBRAHÈM KHALÈL KHAN JAVANSHER". Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- Tapper, Richard (1997). Frontier Nomads of Iran: A Political and Social History of the Shahsevan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-521-47340-3.

- Mikaberidze 2011, p. 409.

- Donald Rayfield. Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia Archived 2015-07-06 at the Wayback Machine Reaktion Books, 15 feb. 2013 ISBN 1780230702 p 255

- Fisher et al. 1991, p. 128.

- Fisher et al. 1991, p. 126.

- Michael Axworthy. Iran: Empire of the Mind: A History from Zoroaster to the Present Day Archived 2015-06-10 at the Wayback Machine Penguin UK, 6 nov. 2008 ISBN 0141903414

- Fisher et al. 1991, p. 329.

- "EBRĀHĪM ḴALĪL KHAN JAVĀNŠĪR – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Encyclopædia Iranica. 15 December 1997. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Yunus, Arif. Karabakh: past and present Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Turan Information Agency, 2005. page 29

- Allen F. Chew. "An Atlas of Russian History: Eleven Centuries of Changing Borders". Yale University Press, 1967. pp 74.

- Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine pp 729-730 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014. ISBN 978-1598849486

- The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. 1833.

- Bournoutian, George A. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-E Qarabagh. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1994, page 18

- Waal, Thomas de (2013). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War, 10th Year Anniversary Edition, Revised and Updated Archived 2015-11-23 at the Wayback Machine NYU Press. ISBN 978-0814760321 p 201

- Waal, Thomas de (2013). "Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War, 10th Year Anniversary Edition, Revised and Updated" Archived 2015-11-23 at the Wayback Machine NYU Press. ISBN 978-0814760321 p 201

- Mkrtchyan, Shahen. Historical-Architectural Monuments of Nagorno Karabagh. Yerevan, 1989, p. 341.

- Hovannisian, Richard (1971). The Republic of Armenia: Volume 1, The First Years, 1918–1919. Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-520-01805-2.

- Tim Potier. Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal. ISBN 90-411-1477-7

- Tadeusz Swietochowski. Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. ISBN 0-231-07068-3

- Mutafyan Claude (1994) "Karabagh in the twentieth century." In Chorbajyan Levon, Donabedian Patrick and Mutafian Claude (eds.) The Caucasian Knot: The History and geo-politics of Nagorno-Karabakh. London: Zed Books, pp. 109–170.

- Michael P. Croissant. The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict: Causes and Implications. ISBN 0-275-96241-5 p. 16

- Walker J. Christopher (ed.) (1991) Armenia and Karabakh: The Struggle for Unity. London: Minority Rights Group.

- "The Nagorno-Karabagh Crisis: A Blueprint for Resolution" (PDF). Public International Law & Policy Group and the New England School of Law. June 2000. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2004. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

In August 1919, the Karabagh National Council entered into a provisional treaty agreement with the Azerbaijani government. Despite signing the Agreement, the Azerbaijani government continuously violated the terms of the treaty.

- Mutafian, Claude (1994). "Karabagh in the Twentieth Century". In Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian, Patrick; Mutafian, Claude (eds.). The Caucasian Knot: the History and Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabakh. London: Zed Books. pp. 124–126. ISBN 1856492885.

In November the Karabagh Armenians rejected proposals for further submission presented by an Azerbaijani governmental delegation which demonstrated the weakness of the August accords... Sultanov took control of the Karkar Valley while massacring the Armenian population of several villages on 22 February, including Khankend (present-day Stepanakert).

- Tim Potier. Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal

- Benjamin Lieberman. Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. ISBN 1-56663-646-9

- "Chronology: Accord Nagorny Karabakh". c-r.org. 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Richard G. Hovannisian. The Republic of Armenia, Vol. III: From London to Sèvres, February–August 1920

- Archived 2016-03-07 at the Wayback Machine Audrey L. Altstadt. Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity Under Russian Rule. Hoover Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8179-9182-4, ISBN 978-0-8179-9182-1, p. 103

- Thomas de Waal. Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9

- "The Nagorno-Karabagh Crisis: A Blueprint for Resolution" (PDF). Public International Law & Policy Group and the New England Center for International Law & Policy. June 2000. p. 3.

In August 1919, the Karabagh National Council entered into a provisional treaty agreement with the Azerbaijani government. Despite signing the Agreement, the Azerbaijani government continuously violated the terms of the treaty. This culminated in March 1920 with the Azerbaijanis' massacre of Armenians in Karabagh's former capital, Shushi, in which it is estimated that more than 20,000 Armenians were killed.

- (in Russian) Институт Истории АН Армении, Главное архивное управление при СМ Республики Армения, Кафедра истории армянского народла Ереванского Государственного Университета. Нагорный Карабах в 1918-1923 гг. Сборник документов и материалов. Ереван, 1992. Документ №443: из письма члена компартии Азербайджана Оджахкули Мусаева правительству РСФСР. стр. 638-639 (Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of Armenia, the Main archival department at Ministerial council of Republic Armenia, Faculty of history of Armenian people of the Yerevan State University. Nagorny Karabakh per 1918–1923. Collection of documents and materials. Yerevan, 1992. The document №443: from the letter of a member of the communist party of Azerbaijan Ojahkuli Musaev to the government of RSFSR. рр. 638–639)

- (in Russian) Н. Я. Мандельштам. Книга третья. Париж, YMCA-Ргess, 1987, с.162–164.

- "Nagorno-Karabakh Searching for a Solution, US Institute for Peace report". Archived from the original on 10 January 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- "Groups: Azerbaijanian, Centre for Russian Studies". nupi.no. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Шуша - цитадель Карабаха: почему она важна для азербайджанцев и армян" [Shusha is the citadel of Karabakh: why is it important for Azerbaijanis and Armenians]. BBC Russian Service (in Russian). 7 November 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Rafiqoğlu, Aqşin (6 May 2010). "Şuşanın işğalı ilə bağlı beynəlxalq təşkilatlara bəyanat ünvanlanıb" [A statement was made to international organizations on the occupation of Shusha] (in Azerbaijani). ANS Press. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- de Waal, Thomas (10 May 2002). "Shusha Armenians Recall Their Bittersweet Victory". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- de Waal, Thomas (2003, 2013). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace And War. (10th Year Anniversary edition, revised and updated) New York University Press, pp. 196-197

- "Война в Карабахе: Азербайджан и Армения заявляют о новых боях и обстрелах - Новости на русском языке". BBC News Русская служба (in Russian). Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- @cavidaga (8 October 2020). "AzMOD on Ghazanchetsots" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Troianovski, Anton (18 October 2020). "At Front Lines of a Brutal War: Death and Despair in Nagorno-Karabakh". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020.

Manushak Titanyan, an architect in Nagorno-Karabakh, has already lost one of her buildings to the violence: the House of Culture in the hilltop town of Shusha, its roof gone, a piece of it stuck in a tree across the street, the plush red seats coated in dust, the stage curtain tangled amid the rubble.

- "Azerbaijani leader: Forces seize key Nagorno-Karabakh city". Associated Press. 8 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Нагорный Карабах заявил о потере контроля над городом Шуши". RBK (in Russian). 9 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Узел, Кавказский. "Армянская церковь заявила об осквернении собора в Шуши". Кавказский Узел. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- "Армянская церковь обвинила азербайджанцев в осквернении собора в Шуши". РБК (in Russian). Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Maranci, Christina. "Armenians displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh fear their medieval churches will be destroyed". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Mosque and fountain in Mamay district of Shusha were vandalized by Armenians - PHOTO". Milli.az (in Azerbaijani). 25 January 2021. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Crossroads and Conflict: Security and Foreign Policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia, by Gary K. Bertsch - 2000 - 316 pages, p. 297

- Mattew O'Brien. Uzeir Hajibeyov and His Role in the Development of Musical Life in Azerbaijan. – Routledge, 2004. – С. 211. – ISBN 0-415-30219-6, 9780415302197

- Aliyev, Jeyhun (5 January 2021). "Azerbaijan declares city of Shusha 'cultural capital'". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, "Azerbaijan": Cultural life, Online Academic Edition, 2007.

- Looking toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History, by Ronald Grigor Suny - 1993 - 289 pages, p. 195

- A Typographical Gazetteer, by Henry Cotton - 2008 - p. 206

- Barkhudaryan, Makar (1895). Artsakh (in Armenian). Baku: "Aror" Publishing House. pp. 137–138.

- "Diocese of Artsakh of the Armenian Apostolic Church". Gandzasar.com. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, "sileh rug", Online Academic Edition, 2007.

- Nazimgizi, Shafiga (18 November 2020). "Shusha may host Turkvision Song Contest". Report Information Agency. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Azerbaijan launches preparation for Khari Bulbul festival, Days of Vagif's Poetry in Shusha (PHOTO)". International News.az. 21 January 2021. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ""Шуша" в Большой Советской Энциклопедии". Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Petrosyan, Sara (25 January 2021). "Shushi's Museums: Most Collections Now in Azerbaijani Hands". hetq.am. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- (in Russian) Caucasian Calendar (Кавказский Календарь), 1853, p. 128

- "население нагорно-карабахской республики". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011.

- (in Russian) г. Шуша Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Демоскоп Weekly

- "Шуша". Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: In 86 Volumes (82 Volumes and 4 Additional Volumes). St. Petersburg. 1890–1907.

- (in Russian) Caucasian Calendar (Кавказский Календарь), 1917, p. 190

- "Шушинский район 1939". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- "Шушинский район 1959". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- "Шушинский район 1970". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- "Шушинский район 1979". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- de Waal, Thomas (2013). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. NYU Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780814785782.

- "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". www.demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- Amirbayov, Elchin. "Shusha's Pivotal Role in a Nagorno-Karabagh Settlement" in Dr. Brenda Shaffer (ed.), Policy Brief Number 6, Cambridge, MA: Caspian Studies Program, Harvard University, December 2001, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- De facto and De Jure Population by Administrative Territorial Distribution and Sex Archived 2011-03-02 at the Wayback Machine Census in NKR, 2005. THE NATIONAL STATISTICAL SERVICE OF NAGORNO-KARABAKH REPUBLIC

- "Statistical yearbook of NKR 2003–2009" (PDF). stat-nkr.am. National Statistical Service of Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. p. 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- "Review of Russian possessions in Transcaucasus" ("Obozreniye Rossiyskih vladeniy za Kavkazom"), vol. III, St.-Petersburg, 1836, p. 308

- George Thomas Keppel; earl of Albemarle. Personal Narrative of a Journey from India to England. ISBN 1-4021-9149-9.

- "Description of the Karabakh province prepared in 1823 according to the order of the governor in Georgia Yermolov by state advisor Mogilevsky and colonel Yermolov 2nd," as quoted above

- (in Russian) Caucasian Calendar (Кавказский Календарь), 1886, p. 319

- "Review of the Yelizavetpol goubernia as of 1910" ("Obzor Yelizavetpolskoy goubernii za 1910 g." in Russian) Tbilisi, 1912 p. 141

- "Шуша - цитадель Карабаха: почему она важна для азербайджанцев и армян" [Shusha is the citadel of Karabakh: why is it important for Azerbaijanis and Armenians]. BBC Russian Service (in Russian). 7 November 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Fatullayev, Eynulla (19 January 2012). "Карабахский дневник" азербайджанского журналиста. Novoye Vremya (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

Как ни странно, но Шушу в основном заселили бакинские армяне, и в целом город сохранил свой традиционно интеллигентный состав населения. Всюду в Шуше я встречал тепло и ностальгию бакинцев по старому Баку.

- Antanesian, Vahe (8 May 2014). "Շուշի [Shushi]". Asbarez (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

Շուշիում ներկայումս բնակւում է 3000 մարդ, որոնք հիմնականում փախստականներ են Բաքուից:

- "Armenian Karabakh Official Says Mosques Being Repaired". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

Town residents, many of them former Armenian refugees from Baku and other parts of Azerbaijan...

- Beglarian, Ashot (15 June 2007). "Karabakh: A Tale of Two Cities". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

Now Baku’s Armenians are scattered all over the world, with many in Shusha. Saryan noted that Shusha is also home to Armenians who lost their homes in Mardakert and Hadrut...

- Bardsley, Daniel (21 July 2009). "Shusha breathes new life after years of strife". The National. Abu Dhabi. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

Now, the only residents of Shusha are 4,000 Armenians; all of the Azeris fled during the fighting.

- "Azerbaijani residents to return to Shusha in Karabakh by next summer?". JAMnews. Baku. 21 December 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- Berberian, Viken (21 December 2020). "Armenia's Tragedy in Shushi". The New York Review. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 December 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Holding, APA Information Agency, APA. "Gyöngyös city of Hungary fraternize with Azerbaijan's occupied town of Shusha - PHOTOSESSION". apa.az. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

Sources

- Chkeidze, Thea (2001). "GEORGIA v. LINGUISTIC CONTACTS WITH IRANIAN LANGUAGES". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 5. pp. 486–490.

- Everett-Heath, John (2018). "Shusha". The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0191866326.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G.; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200954.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Shusha. |

- Shusha at GEOnet Names Server

- Shusha: from A to Z

- Shusha – the town of the dead. Photo-report.

- Shusha by Travel-images.com

- Shoushi Foundation

- Shushi portal Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Armenian Guidebook Chapter on Shushi

- Armeniapedia entry on Shushi

- "The Twentieth Spring" – A photo essay on Shushi 20 years after it was taken over by Armenian forces (randbild | 2011)

- Historical neighborhoods of Shusha

.svg.png.webp)