Valenzuela, Metro Manila

Valenzuela (/ˌvælənzjuˈɛlə/), officially the City of Valenzuela (Tagalog: Lungsod ng Valenzuela), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in Metropolitan Manila, Philippines. According to the 2015 census, it has a population of 620,422 people. [6]

Valenzuela | |

|---|---|

| City of Valenzuela | |

Clockwise from top-left: Hall of Justice; Pío Valenzuela Residence; People's Park; San Diego de Alcala Church; Valenzuela City Hall | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "Northern Gateway to Metropolitan Manila"; "The Vibrant City"; "The City of Discipline" | |

| Motto(s): "Tayo na, Valenzuela!"

"Valenzuela, May Disiplina" | |

| Anthem: Himig Valenzuela Valenzuela Hymn | |

Map of Metro Manila with Valenzuela highlighted | |

OpenStreetMap

| |

.svg.png.webp) Valenzuela Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 14°42′N 120°59′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | National Capital Region (NCR) |

| Province | none |

| District | 1st and 2nd districts |

| Founded | November 12, 1623[1][2] |

| Cityhood and HUC | December 30, 1998[3] |

| Founded by | Juan Taranco and Juan Monsód |

| Named for | Pío Valenzuela |

| Barangays | 33 (see Barangays) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Panlungsod |

| • Mayor | Rexlon T. Gatchalian |

| • Vice Mayor | Lorena C. Natividad-Borja |

| • Representative , 1st District | Weslie T. Gatchalian |

| • Representative , 2nd District | Eric M. Martinez |

| • Electorate | 378,013 voters (2019) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 47.02 km2 (18.15 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 119th of 145 cities |

| Elevation | 22 m (72 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 620,422 |

| • Rank | 13th of 145 cities |

| • Density | 13,000/km2 (34,000/sq mi) |

| • Households | 147,161 |

| Demonym(s) | Valenzuelaño Valenzuelano |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | 1st city income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 3.56% (2015)[7] |

| • Revenue | ₱2,879,637,025.94 (2016) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | 1440–1448, 1469, 0550, 0560 |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)02 |

| Climate type | tropical monsoon climate |

| Native languages | Tagalog |

| Website | www |

It is the 13th most populous city in the country and is located about 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) north of Manila, the nation's capital. Valenzuela is categorized under Republic Act Nos. 7160 and 8526 as a highly urbanized, first-class city based on income classification and number of population.[8][9][10] A landlocked chartered city located on the island of Luzon, it is bordered by the province of Bulacan, and cities of Caloocan, Malabon and Quezon City. Valenzuela shares border and access to Tenejeros-Tullahan River with Malabon. It has a total land area of 45.75 square kilometers, where its residents are composed of about 72% Tagalog people followed by 5% Bicolanos with a small percentage of foreign nationals.

Valenzuela was named after Pío Valenzuela, a physician and a member of the Katipunan, a secret society founded against the colonial government of Spain. The city, as a town, was originally called as Polo, initially formed in 1621 after separation from Meycauayan, Bulacan. The Battle of Malinta of the Philippine–American War was fought in Polo in 1899. In 1960, President Carlos P. Garcia ordered the split of Polo's southern barangays to form another town named as Valenzuela. The split was revoked by President Diosdado Macapagal in 1963 after political disagreements and the new merged town was named Valenzuela. The modern-day Valenzuela with its borders was chartered in 1998.

Owing to the cross-migration of people across the country and its location as the northernmost point of Metro Manila, Valenzuela has developed into a multicultural metropolis. A former agricultural rural area, Valenzuela has grown into a major economic and industrial center of the Philippines when a large number of industries relocated to the central parts of the city.[11]

Toponymy

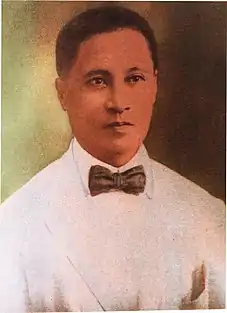

In Spanish, Valenzuela is a diminutive form of Valencia which means "little Valencia".[12] The name Valenzuela is also the surname of Pío Valenzuela y Alejandrino, a Tagalog physician and was one of the leaders of Katipunan. He was regarded as a member of the Katipunan triumvirate which started the Philippine Revolution against Spanish colonial authorities in 1896. He also served as the provisional chairman for the Katipunan.[13][14]

Before 1960, Valenzuela was formerly known as Polo.[15] The name Polo was derived from the Tagalog term pulô, which means "island" or "islet", although the area was not an island itself. The town of Polo was entirely surrounded by the rivers, thus, creating an impression of itself being an island.[16]

History

Spanish era

During the Spanish era, present-day Valenzuela, Obando and Novaliches (now in Quezon City) were parts of Bulacan. Areas now covered by Valenzuela included four haciendas (Malinta, Tala, Piedad, and Maysilo), small political settlements and a Spanish garrison.[17] These areas were known as Polo. The region was bounded by the Tullahan River on the south and streams of branching Río Grande de Pampanga on some areas.

When Manila became an archdiocese in 1595, regular friars who had already established permanent churches in Catanghalan, Bulacan (now Meycauayan) decided that the sitio of Polo be separated from the town and have its own church to cater its increasing spiritual needs. Through successive efforts of Franciscan friar Juan Taranco and Don Juan Monsód, sitio Polo was successfully separated from Catanghalan on November 7, 1621, at the feast day of the town's new patron, St. Didacus of Alcalá, known locally as San Diego de Alcalá.[18] The first cabeza de barangay of Polo was Monsód, while Taranco run the parish on a small tavern, which would become the present-day San Diego de Alcalá church.[19] The separation was then confirmed by Governor-General Alonso Fajardo de Entenza in a proclamation letter on November 12, 1623. Later, the date of November 12 is adopted as the foundation day of the city.[1][2]

The construction of a parochial church dedicated to St. Didacus of Alcalá started in 1627, under the supervision of Fr. José Valencia and Juan Tibay. The first church structure was completed in 1632. But its bell was looted during the Chinese uprising of 1635. At that time, Chinese merchants resided specifically in Barrio Pariancillo, which was located at the back of the church. In 1852, the church was repaired and remodeled under the direction of Fr. Vicente. The church was later re-dedicated to another patron, to thenuestra señora de la Inmaculada Concepción. A convent was also built followed by a common house (casa tribunal) that had a rectangular prison cell and a school house made of stone.[20] On June 3, 1865, a strong earthquake destroyed the belfry of the San Diego de Alcalá Church, followed by an epidemic that killed thousands of people.[21]

A new pueblo was carved out of the northwestern area of Polo on May 14, 1753, by the orders of the Governor-General Francisco Jose de Obando y Solis, Marquis of Brindisi. The new town was named Obando in honor of the governor general, and was incorporated to Bulacan.[20]

In 1762-1764 British occupation of Manila and surrounding suburbs the colonial government led by Simón de Anda y Salazar fled to Bacolor, Pampanga through Polo. The British followed Anda, and at one point stayed in sitio Mabolo while waiting for orders from the British civil Governor Dawsonne Drake. They explored the nearby communities of Malanday, Wakas, Dalandanan, Pasolo, Rincon and Malinta. The terrified local population fled and sought refuge in the forests of Viente Reales, where many of them died of malaria.[22] The British then proceed to Malolos, Bulacan where they were ambushed by the stationed Spanish soldiers. After the chase, the local population of Polo returned to their homes on May 12, 1763, after days of reconstruction. The day May 12 was commemorated as the feast of St. Roch, locally known as San Roque, as another patron saint and as a memorial to those who died in the Seven Years' War.[22]

In 1854, General Manuel Pavía y Lacy, Marquis de Novaliches, was named Governor-General of the Philippine Islands. He arrived in Manila with the task of establishing a penal colony where prisoners would be granted lands they would develop in exchange for their release. The colony was given the name Hacienda Tala since the once heavily forested area became identical to one where a star (“tala”) had fallen after clearing. This hacienda grew into a larger community that eventually merged with the haciendas of Malinta and Piedad in forming the independent town of Novaliches on January 26, 1856.[23] A new road from Polo to Novaliches opened and traversed the barrios of Mabolo, Pasolo, Rincon, Malinta, Masisan, Paso de Blas, Canumay and Bagbaguin.

In 1869, Filipino physician and patriot Pío Valenzuela was born in Polo. He would be later known as one of the key leaders of the Katipunan, which he joined in 1892 at the age of 23. His admission to the society led to the more recruits from Polo, including Ulpiano Fernández, Gregorio Flamenco, Crispiniano Agustines, and Faustino Duque. When Valenzuela was the chief editor, Fernández held a special role in the Katipunan as a printer of the Ang Kalayaan, the organization's official newspaper.[24]

The now-defunct Manila-Dagupan Railway opened in 1892 and traversed the barrios of Marulas, Caruhatan, Malinta, Dalandanan and Malanday, with the station being in Dalandanan.[25]

A constituted branch of the Katipunan was established in Polo on February 1, 1896.[26] The town joined other revolutionaries when the Philippine Revolution broke out on August 1896, while Valenzuela availed the amnesty offered by Spanish authorities few weeks later.[27] One of the notable battles in Polo occurred in sitios Bitik and Pasong Balite in Pugad Baboy, where the locals won under the command of General Tiburcio de León y Gregorio.[28] During the revolution, the Spanish massacred many residents, most of them in Malinta. Suspected revolutionaries were hanged and tortured to death. Many were forced to admit guilt or shout innocent names; others were shot without trial.[29]

American era

The Americans imposed a military government when they acquire the Philippine islands from Spain as part of the peace treaty of the Spanish–American War. They appointed Pío Valenzuela as the first municipal president of (presidente municipal) on September 6, 1899, to suppress aggressive leadership in the area. He resigned in February 1901 to become the head of the military division and an election was held. Later that year, the government proclaimed Rufino Valenzuela, a relative of Pío as the second president and first elected municipal president of the town.[30]

When the Philippine–American War broke out in early 1899, the Americans were directed to capture Emilio Aguinaldo who was escaping to Malolos, Bulacan. Polo was one of the towns where Aguinaldo retreated, thus it received heavy casualties on the first stages of the war.[31] On February 22, 1899, General Antonio Luna camped at Polo after an unsuccessful engagement with the American forces in Caloocan.[31][32][33] A bloody battle on March 26, 1899, happened near the barrio chapel of Malinta. The Filipino forces had to retreat with arrival of American reinforcements after being were initially successful in defending Malinta and killing Col. Harry Egbert.

In 1910, a stone arch was built at the boundary of Polo, Bulacan and Malabon, Rizal along Calle Real. In 1928, McArthur Highway opened and became the new gateway. The once-agricultural town slowly shifted to industrial. Businesses soon put up factories, the most famous of which is the Japanese venture Balintawak Beer Brewery that opened in 1938.

Japanese occupation

The entrance of the Japanese in Polo during the Second World War was met with almost no resistance. However, there were too many murders committed. The place became a center of Makapili and spies who troubled the peaceful civilians. It was found that the Balintawak Beer Brewery became front for manufacturing ammunition for the Japanese forces. The sudden appearance of the Japanese added terror to the place. The old church of San Diego de Alcalá became a torture house during WWII.

The reign of terror climaxed on December 10, 1944. It was a day of mourning for the people of Polo and Obando when the Japanese massacred more than a hundred males in both towns. About 1:00 AM on this day up to the setting of the sun cries could be heard from the municipal building when males were tortured to death. Mayor Feliciano Ponciano met the same fate when he died on a cruel death together with other municipal officials.[34]

When liberation came, the town was partly burned by the approaching the military forces of combined Filipino and American regiments who used flamethrowers. They bombed and shelled big houses in the town not exempting even the more than 300 years old church of San Diego.[34]

The historical old bridge connecting northern and southern areas of the town was destroyed by the Japanese, thus separating Polo in two parts. The northern part was at once liberated by joint Filipino and American troops while the southern part, which includes the municipal center poblacion was still under the Japanese banner. The Japanese abandoned the town on February 11, 1945, when the combined troops were able to cross the river and took the town.

In 1947, the Balintawak Beer Brewery was acquired by San Miguel Beer. The Spanish church was never rebuilt and only the belfry and the entrance arch remained. A new church was built perpendicular to the ruins of the old one.

Modern history

On July 21, 1960, President Carlos P. Garcia signed Executive Order No. 401 which divided Polo into two: Polo and Valenzuela. Polo comprised the northern barangays of Wawang Pulo, Poblacion, Palasan, Arkong Bato, Pariancillo Villa, Balangkas, Mabolo, Coloong, Malanday, Bisig, Tagalag, Rincon, Pasolo, Punturin, Bignay, Viente Reales, and Dalandanan. Valenzuela, on the other hand, comprised the southern barangays of Karuhatan, Marulas, Malinta, Ugong, Mapulang Lupa, Canumay, Maysan, Parada, Paso de Blas, Bagbaguin and Torres Bugallón (now Gen. T. de Leon). A provisional town hall was built in front of today’s SM Valenzuela, until a permanent town hall was built near the intersection of MacArthur Highway and the old Polo-Novaliches Road.

The division soon proved to be detrimental to economic growth in each town, so Bulacan Second district Representative to the Fifth Congress Rogaciano Mercado and Senator Francisco Soc Rodrigo filed a bill which sought the reunification of the two towns. On September 11, 1963, President Diosdado Macapagal signed Executive Order No. 46 which reunified Valenzuela and Polo, adapting Valenzuela as the name of the resulting town.[35]

In 1967, mayor Ignacio Santiago, Sr. bought lots in Karuhatan in which the new municipal hall would be built. Misinterpretation of property surveys and tax appropriation issues sparked the debate on which barangay should the municipal hall be belonged to: Karuhatan, Malinta, or Maysan. To resolve the issue, Santiago ordered the creation of a new barangay which was called Poblacion II, a reference to the old Poblacion barangay.[36]

On November 7, 1975, jurisdiction over Valenzuela was moved from the province of Bulacan to Metro Manila. Metro Manila was then headed by First Lady Imelda Marcos as its governor. Due to this, Valenzuela is the only area in the modern National Capital Region that was not part of either Spanish colonial-era Manila or Rizal province.[37]

In 1968, the North Diversion Road (now North Luzon Expressway) was opened. In the same year, MacArthur Highway was extended through Valenzuela. Both highways connect Manila to northern provinces of the Philippines.[38]

Rail transport to the city ceased in 1988 with the closure of the Philippine National Railway's North Line.

The passage of the Local Government Code in 1991 provided local governments autonomy which has allowed them develop into self-reliant communities. On February 14, 1998, President Fidel V. Ramos signed Republic Act No. 8526, which converted the municipality of Valenzuela into a highly urbanized chartered city. The law also ordered the division of the newly created city into two legislative districts.[8] When the law was ratified on December 30, 1998, Valenzuela became the 12th city to be admitted in Metro Manila and the 83rd in the Philippines.[39][40]

In 2002, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo proclaimed July 11 every year as Valenzuela Day, which was an official holiday in the city that commemorates the birth date of Pío Valenzuela.[18] However, in 2008, the date of the city's charter day was transferred to February 14. Today, Valenzuela City celebrates Valenzuela Day and Valenzuela Foundation Day on February 14 and November. 12 respectively[2][41]

On May 13, 2015, a fire broke out in Kentex Manufacturing factory in barangay Ugong, killing 74 people in the incident. In 2016, the Ombudsman ordered the dismissal of mayor Rex Gatchalian and other city officials due to grave misconduct and negligence of duty during the incident.[42] This is dubbed as the third worst fire incident in the country.[43]

On March 15, 2020, the city and the entire metropolitan Manila was placed under community quarantine for one month due to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

Geography

Valenzuela is located at 14°40′58″N 120°58′1″E and is about 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) north of country's capital, Manila. Manila Bay, the country's top port for trade and industry is located about 16.3 kilometres (10.1 mi) west of the city. Valenzuela is bordered in the north by the town of Obando and the city of Meycauayan in Bulacan, the city of Navotas in the west, Malabon in the south, and Quezon City and northern portion of Caloocan in the east.

The highest elevation point is 38 metres (125 ft) above sea level. Having a surface gradient of 0.55% and a gentle slope, hilly landscape is located in the industrial section of the city in Canumay. The average elevation point is 2 metres (6.6 ft) above sea level.[44]

Apart from the political borders set by the law, Valenzuela and Malabon is also separated by the 15-kilometer Tenejeros-Tullahan River or simply Tullahan River.[45] The river obtained its name from tulya or clam due to the abundance of such shellfish in the area.[46] Tullahan is a part of the Marilao-Meycauayan-Obando river system of central Luzon.[47] It is now considered biologically dead and one of the dirtiest river system in the world.[47][48] Tullahan riverbanks used to be lined with mangrove trees and rich with freshwater fish and crabs. Children used to play in the river before it was polluted by developing industries near it.[47]

In an effort to save the river, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Metropolitan Manila Development Authority and the local governments of Valenzuela and Malabon signed partnerships with private and non-government organizations to dredge the area.[45][48][49]

Increased climate variability, that is associated with global warming, has brought with it periods of heavy rainfall and high tides which in turn results in stagnant water which can stay in the area for up to 4 weeks due to insufficient drainage and improper solid waste disposal. People are often stranded inside their homes and are exposed to water-borne diseases such as dengue and leptospirosis. Better early warning systems are needed to manage the risk associated with increased rainfall.[50]

Climate

| Valenzuela | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Due to its location in Metro Manila, rainfall and climate in Valenzuela is almost similar to the country's capital Manila. The location of Valenzuela in the western side of the Philippines made Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAG-ASA) to classify its weather scheme as Type I. Wind coming from the Pacific Ocean is generally blocked by the Sierra Madre mountain range, several kilometers east of the city.[51]

Its proximity to the equator tends to make its temperature to rise and fall into very small range: from as low as 20 °C (68 °F) to as high as 35 °C (95 °F), although humidity makes these warm to hot temperatures feel much hotter. The Köppen climate system classifies Valenzuela climate as a borderline tropical monsoon (Am) and tropical savanna (Aw) due to its location and precipitation characteristics. This means that the city has two pronounced seasons: dry and wet seasons.

Humidity levels are usually high in the morning especially during June–November which makes it feel warmer. Lowest humidity levels are recorded in the evening during wet season. Discomfort from heat and humidity is extreme during May and June, otherwise it is higher compared to other places in the country. Average sunlight is maximum at 254.25 hours during April and minimum at 113 hours during July, August and September.[52]

| Climate data for Valenzuela, Philippines | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.4 (90.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

31.4 (88.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23 (73) |

22.2 (72.0) |

23.3 (73.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18 (0.7) |

10 (0.4) |

13 (0.5) |

30 (1.2) |

159 (6.3) |

318 (12.5) |

477 (18.8) |

503 (19.8) |

369 (14.5) |

194 (7.6) |

140 (5.5) |

65 (2.6) |

2,296 (90.4) |

| Source: en.climate-data.org[53] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

The vegetation in Valenzuela was originally covered with grasslands suitable for agriculture. Because of rapid development of industries and economy, land use converts grass covers into cemented roads. However, the government put into efforts of preserving vegetation such as constructing community vegetable gardens and techno-demo farms all over the city. In 2003, these gardens numbered up to two functioning farms.[54]

Flora and fauna in Valenzuela includes the common plants and animals found in Luzon, such as domesticated mammals. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau declared a two-hectare mangrove/swampy area in Villa Encarnacion, barangay Malanday as an ecotourism site.[55] Every year, about 100 species of migratory birds such as black-crowned night herons (Nycticorax nycticorax) and other native birds such as moorhen (Gallinula sp.), swamphen (Porphyrio sp.) and Philippine duck (Anas luzonica) flock the area. Wooden view decks are built to facilitate spectators, enthusiasts and visitors while having bird watching and counting activities.[56] As of 2020 the said ecotourism site is no longer the Villa Encarnacion today, The area has been changed and Many Individuals built a house on the side of the main road. The Forest Look like that the wildlife go into are now gone and will become another subdivision, This will be one of Dulalia Subdivision on barangay Malanday.

In 2007, ordinary fishing ponds in Tagalag and Coloong were transformed into fishing spots which attracts anglers every year for a prize catch. Fish tournaments are held every year to increase tourism and livelihood in the area.[57]

In 2008, the Supreme Court of the Philippines mandated Regional Trial Court branch 171 as an environmental court handling all environment cases in Valenzuela.[58]

Thomas Hodge-Smith noted in 1939 that Valenzuela is rich of black tektites occurring in spheroidal and cylindrical shapes and are free of bubbles.[59]

Government and politics

Like other cities in the Philippines, Valenzuela is governed by a mayor and a vice mayor who are elected to three-year terms. The mayor is the executive head who leads the city's departments in the execution of city ordinances and delivery of public services. The vice mayor heads a legislative council that is composed of 14 members: six councilors from each of the city's two districts, and two ex officio offices held by the Association of Barangay Chairmen President as the barangay sector representative and the Sangguniang Kabataan Federation President as youth sector representative. The council is in charge of creating the city's policies in the form of ordinances and resolutions.[8]

The city is geographically part of, but not politically related to, the third district of Metro Manila.

City officials

The incumbent mayor and vice mayor of the city are Rexlon T. Gatchalian and Lorena C. Natividad-Borja, respectively.

| Designation | First district | Second district |

|---|---|---|

| Representatives | Weslie T. Gatchalian (NPC) | Eric M. Martinez (PDP–Laban) |

| Mayor | Rexlon T. Gatchalian (NPC) | |

| Vice Mayor | Lorena C. Natividad-Borja (NPC) | |

| Councilors | Walter Magnum D. dela Cruz (NPC) | Chiqui Marie N. Carreon (NPC) |

| Ramon L. Encarnacion (NPC) | Kimberly Ann D. Galang-Tiangco (NPC) | |

| Ricardo Ricarr C. Enriquez (NPC) | Niña Sheila B. Lopez (NPC) | |

| Rovin Andrew M. Feliciano (PDP–Laban) | Louie P. Nolasco (NPC) | |

| Joseph William D. Lee (NPC) | Crissha Charee M. Pineda-Soledad (NPC) | |

| Jennifer P. Pingree-Esplana (NPC) | Kristian Rome T. Sy (NPC) | |

| ABC President | Bienvenido Bartolome (Bisig) | |

| SK President | Exequiel Serrano (Coloong) | |

Administrative division

Valenzuela is composed of 33 barangays, the smallest administrative unit in the city. A barangay is equivalent to an American village and a British ward. The barangay is headed by the barangay captain or punong barangay and his 7-manned local council or mga kagawad duly elected by the residents. Youth sector of the barangay is represented by the youth council called the Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) headed by the SK chairperson and his 7-manned assembly, also known as mga SK kagawad. There are 33 punong barangays and 231 kagawads in Valenzuela; SK officials are also of the same number. The barangays also serve as census areas of the city.

In the national level, Valenzuela is divided into two congressional districts: the first legislative district which contains 24 barangays in the northern half of the city, while the second legislative district contains the remaining 9 barangays of the southern portion of the city. Unlike barangays, legislative districts has no political leader, but are represented by congressional representatives in the House of Representatives of the Philippines.

| Barangay | District | Area (ha) | Population

(2015)[60] |

Density

(per ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkong Bato | 1st | 34.40 | 10,004 | 290.814 |

| Bagbaguin | 2nd | 159.10 | 13,770 | 86.55 |

| Balangkas | 1st | 73.30 | 11,892 | 162.24 |

| Bignay | 1st | 268.80 | 27,059 | 100.67 |

| Bisig | 1st | 45.60 | 1,333 | 45.6 |

| Canumay East | 1st | 217.30 | 28,213 | 57.35 |

| Canumay West | 1st | 141.30 | 22,215 | 157.22 |

| Coloong | 1st | 223.80 | 11,154 | 49.84 |

| Dalandanan | 1st | 93.90 | 18,733 | 199.50 |

| Gen. T. de Leon | 2nd | 366.90 | 89,441 | 243.77 |

| Isla | 1st | 39.60 | 4,793 | 121.04 |

| Karuhatan | 2nd | 190.60 | 40,996 | 215.09 |

| Lawang Bato | 1st | 287.50 | 19,301 | 67.13 |

| Lingunan | 1st | 115.90 | 21,217 | 183.06 |

| Mabolo | 1st | 115.00 | 1,217 | 10.58 |

| Malanday | 1st | 295.60 | 17,948 | 60.72 |

| Malinta | 1st | 174.10 | 48,397 | 277.98 |

| Mapulang Lupa | 2nd | 140.80 | 27,354 | 194.28 |

| Marulas | 2nd | 224.70 | 53,978 | 240.22 |

| Maysan | 2nd | 253.30 | 24,293 | 95.91 |

| Palasan | 1st | 15.60 | 6,089 | 390.32 |

| Parada | 2nd | 34.40 | 14,894 | 432.97 |

| Pariancillo Villa | 1st | 5.00 | 1,634 | 326.80 |

| Paso de Blas | 2nd | 155.00 | 13,350 | 86.13 |

| Pasolo | 1st | 79.50 | 6,395 | 80.44 |

| Poblacion | 1st | 3.40 | 372 | 109.41 |

| Polo | 1st | 5.20 | 1,103 | 212.12 |

| Punturin | 1st | 162.20 | 20,930 | 129.04 |

| Rincon | 1st | 24.40 | 6,603 | 270.61 |

| Tagalag | 1st | 101.00 | 3,209 | 31.77 |

| Ugong | 2nd | 307.20 | 41,821 | 136.14 |

| Veinte Reales | 1st | 192.90 | 22,949 | 118.97 |

| Wawang Pulo | 1st | 27.80 | 3,516 | 126.47 |

| Valenzuela | 4,575.10 | 620,422 | 135.61 |

Court system and police

The Supreme Court of the Philippines recognizes five regional trial courts and two metropolitan trial courts within Valenzuela that have an over-all jurisdiction in the populace of the city.

The Valenzuela City Police Station (VCPS) is one of the four city police stations in the Northern Police District under the jurisdiction of the Nation Capital Region Police office.[61] Today, there are more than 500 police officers working for the VCPS, which puts the police-residents ratio in the city at 1:16,000.[62]

In 2007, the Valenzuela City Peace and Order Council, of which the VCPS is a member, was hailed 2nd placer for the Best Peace and Order Council award that was conferred by the Department of Interior and Local Government, the NCRPO, and the Manila Peace and Order Council.[62] In 2012, the VCPS was cited by the NCRPO for having the best Women and Children Protection Desk in the metro.[62]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 8,183 | — |

| 1918 | 9,323 | +0.87% |

| 1939 | 13,468 | +1.77% |

| 1948 | 16,740 | +2.45% |

| 1960 | 41,473 | +7.85% |

| 1970 | 98,456 | +9.02% |

| 1975 | 150,605 | +8.90% |

| 1980 | 212,363 | +7.11% |

| 1990 | 340,227 | +4.83% |

| 1995 | 437,165 | +4.81% |

| 2000 | 485,433 | +2.27% |

| 2007 | 568,928 | +2.21% |

| 2010 | 575,356 | +0.41% |

| 2015 | 620,422 | +1.45% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority [6] [63] [64][65] | ||

The demonym of Valenzuela is Valenzuelano for males and Valenzuelana for females; it is sometimes spelled as Valenzuelaño.

Based on the 2015 census, Valenzuela City has a total population of 620,422, the 7th most populous in the NCR and 13th in the Philippines. This is an increase of 7.8 percent from 575,356 people in 2010, at an annual growth rate of a 1.45%.[60][66]

The five most populous barangays are: Gen. T. de Leon (89,441), Marulas (53,978), Malinta (48,397), Ugong (41,821) and Karuhatan (40,996).[60]

Valenzuela City household population in 2010, on the other hand, is at 574,840.[67] Almost half, 50.2 per cent, are males. Females comprise 49.8 per cent of the population, with a total number of 286, 548. The city has a sex ratio of 101 males for every 100 females, the second highest ratio in the region, after Navotas, which has a sex ratio of 102 males per 100 females.[66] Seven out of ten Valenzuela City residents, 66.7 per cent, belong to the working-age group, or those aged 15 to 64. The remaining 33.3 are aged 0 to below 15 and 65 and above, which are classified as the dependent age group.[67]

City population is expected to reach the 700,000-mark by mid-2022.[68]

Culture

"Himig Valenzuela"

"Himig Valenzuela",[69] or "Valenzuela Hymn", is the official song of the city.[70] It is sung during flag ceremonies of private and public schools as well as government institutions along with the Philippine national anthem, "Lupang Hinirang". The hymn was composed by Edwin Ortega which has the primary objective to promote unity, progress and patriotism among the city's citizens.[71]

City ordinance number 18 mandated all citizens of Valenzuela to sing the hymn in all meetings and public occasions.[71]

Before its adoption in 2008, Valenzuela has its official hymn during its time as municipality, from being part of Bulacan to Metro Manila, called "Bayang Valenzuela", composed by Igmidio M. Reyes and its lyrics by Dr. Eusebio S. Vibar. It is now abandoned its use as official hymn of this city. There is a video by Valenzuela City Cultural and Tourism Development Office, which is found on Facebook.[72]

Feasts and holidays

In 2007, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo signed Republic Act number 9428 which sets February 14 every year as a special non-working holiday to commemorate cityhood of Valenzuela in 1998.[73] On the same hand, November 12 each year is declared by the city government as the city's foundation day, looking back the establishment of then-Polo in 1623. There are misunderstandings before regarding the date of the actual foundation of the town, however, this date was decided by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines to be the town's creation, since Spanish colonizers adopted a town's patron saint feast day as its date of creation.[1][2]

Each barangay in Valenzuela have their own feast. Most of them launch celebrations during May and April to honor patron saints and bounty harvest. Every April 26, a santacruzan is performed along with Santa Cruz Festival in Barangay Isla. A santacruzan is a novena procession commemorating St. Helena's mythical finding of the cross. St. Helena was the mother of Constantine the Great. According to legends, 300 years after the death of Christ, at the age of 75, she went to Calvary to conduct a search for the Cross. After some archeological diggings at the site of the Crucifixion, she unearthed three crosses. She tested each one by making a sick servant lie on all three. The cross where the servant recovered was identified as Christ's. St. Helena's feast day falls on August 8 but the anniversary of the finding of the Cross is on May 3, in the Philippines, this celebration took the form of the Mexican Santa Cruz de Mayo.[74]

Mano Po, San Roque Festival is celebrated every May 12 in Mabolo. In Valenzuela, San Roque is also known as the patron saint of the unmarried. There are countless tales of single girls who danced and prayed in the procession and who claim to have found their husband during the fiesta. The festival is almost similar to Obando Fertility Rites where hopeful romantics dance to San Roque requesting to find their true love.[75] Street dancing and procession along the city's major thoroughfares in commemoration of the feast of San Roque, highlighting the customs and traditional celebration of the festival.[76] This also commemorates townsfolk victory after the British departed the country following the end of Seven Years' War with Spain.[77]

The Feast of San Diego de Alcala is commemorated every November 12 in Poblacion. This is a celebration of the feast of the oldest church in Valenzuela which includes annual boat racing, street dancing and different fabulous activities of the festival.[78] As part of the San Diego de Alcala Feast Day, a unique food festival in the country is celebrated which features the famous putong Polo, the small but classy kakanin which was originally created in the town of Polo.[79] This rice cake was a recipient of Manuel Quezon Presidential Award in 1931 which was cited having its exotic taste and amazingly long shelf-life.[80] The celebration, known as Putong Polo Festival includes a parade featuring artistic creations from the rice cake which showcases creativity among the residents.[81]

Tourism

There are several attractions in Valenzuela City that residents and visitors of the city can enjoy.

The Valenzuela City People's Park or simply People's Park, is an urban park located in a 1.3-hectare lot beside the city hall in barangay Karuhatan. There is an electronically controlled dancing fountain at the park entrance, an aero circle for zumba and other group exercises, garden, children's playground, zoological spaces where animals are displayed to the public, and a 400-seater amphitheater that can host a wide range of activities.[82]

Another facility in the city that boasts of a nature-centered open space and is free to the public is the Valenzuela City Family Park also in Karuhatan. There is a playground, interactive fountain, aviary, fitness machines, amphitheater, and a food park in the park. The park is also pet-friendly, bike-friendly, and accessible to persons with disability.[83]

One of the many initiatives of the city government to create greener spaces, Polo Mini Park was inaugurated on January 21, 2020, six months after the announcement of the rehabilitation of the historical old town square of Polo. The park is adorned with hundred-years old luscious trees, fountain, memorial marker commemorating war veterans and statues of Pío Valenzuela and José Rizal. The park signifies not only a place for relaxation but also marks the historical identity of the City.[84]

In English, Arkong Bato means "arch of stone" which was constructed and built by the Americans in 1910 to serve as borders between the provinces of Bulacan (where Valenzuela or Polo, as it was known before, belonged to) and Rizal. (where Malabon used to be part of) The arch is located along M.H. del Pilar Street, which was once the main gateway to North Luzon before the construction of MacArthur Highway and North Luzon Expressway. After Malabon seceded from Rizal and Valenzuela from Bulacan to become part of Metropolitan Manila in 1975, the arch now marked as the boundary between the two towns and their respective barangays, Barangay Santulan in Malabon and Barangay Arkong Bato in Valenzuela.[85][86]

The Harry C. Egbert Memorial is located in Sitio Tangke Street in Malinta that serves as monument and memorial to Brigadier general Harry Clay Egbert, commanding officer of the 22nd Infantry Regiment of the United States who was mortally wounded here in 1899 during the Philippine–American War. Additionally, Egbert also served the US Army during American Civil War and Spanish–American War.[87]

The Museo Valenzuela (English: Valenzuela Museum) was the house where Dr. Pío Valenzuela, in whose memory the old town of Polo was renamed, was born and saw the best years of his life. This same house was burned recently. Valenzuela's historical and cultural landmark, Museo Valenzuela features collections of artifacts depicting the city's past and continuing development.

The Libingan ng mga Hapon (English: Japanese Cemetery) was built in a 500-square meter lot of the Bureau of Telecommunications compound. The cemetery served thousands of fallen Japanese soldiers during the Philippines Campaign of 1944–45.[85][86]

The National Shrine of Our Lady of Fatima (Tagalog: Pambansang Dambana ng Birhen ng Fatima) is the center of the Fatima apostolate in the country was declared a tourist site in 1982 by the Department of Tourism and a pilgrimage shrine in 2009 by the Diocese of Malolos. It is near the Our Lady of Fatima University.[88] The shrine houses the wooden statue of Our Lady of Fatima, one of the fifty images blessed by Pope Paul VI in 1967 as part of golden celebration of the Marian apparition to three children in Fátima, Portugal.[89] The images were later distributed to churches worldwide, where one of them is intended for the Philippines, however, unclaimed ending up in New Jersey. In 1984, Archbishop of Manila Jaime Cardinal Sin finally claimed the statue and was then transferred under the custody Bahay Maria Foundation, a Philippine-based Marian organization. During People Power Revolution in 1986, it was one of the iconic figures held by revolutionaries to oust the dictator Ferdinand Marcos.[90] On October 17, 1999, the statue was then transferred to the shrine. The feast of Our Lady of Fatima is celebrated every March 7 and May 13.[89][91][92]

Dr. Pío Valenzuela, who became part of the triumvirate of revolutionary society Katipunan and founder of the organ Ang Kalayaan, lived and died in 1956 at the old Residence of Pío Valenzuela along Velilla Street in Barangay Pariancillo Villa, where a marker by the Valenzuela city government was placed in his honor. The present house was built after the war on the site of the old house which once served as venue for secret meetings and gatherings of the Katipunan. The old house was burned during World War II.[85][86]

The San Diego de Alcala Church and its belfry was built in 1632 by the people of Polo. Residents were taken to forced labor to complete the church after the town gained its independence through Father Juan Taranco and Don Juan Monsod. The belfry and entrance arch, which are over four centuries old, are the only parts of the edifice that remain to this day. The main structure was destroyed by bombs during the Japanese occupation. Residents of barangays Polo and Poblacion celebrate the feast day of San Diego de Alcala on November 12 every year, together with the putong polo festival.[79]

Located at Malanday, the Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish Church, was erected on October 17, 1994, to replace the Santo Cristo Chapel, and solemnly declared on June 24, 2001. The Church belongs to the Vicariate of St. Didacus of Alcala – Valenzuela City, Roman Catholic Diocese of Malolos.

The Valenzuela Astrodome is a large multi-purpose, domed sports stadium located in barangay Dalandanan that hosts several sports events, concerts, promotional events, seminars, job fairs, etc.

Dubbed as Valenzuela City's "best kept secret", the Tagalag Fishing Village lies beside a 1.3-kilometer boardwalk in Barangay Tagalag. Various activities are being offered in one of the newest attractions in the city such as recreational fishing, line fishing tutorials, bird watching, boating, photowalk, and sunset watching.[93]

- Gallery of tourist spots in Valenzuela

Polo Mini Park

Polo Mini Park Valenzuela Family Park

Valenzuela Family Park Arkong Bato entry marker

Arkong Bato entry marker

Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish Church

Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish Church

Tagalag Fishing Village

Tagalag Fishing Village

Services

Education

The city collaborates with other institutions, government or private, to bring quality education among its citizens under the "WIN ang Edukasyon Program" (roughly means Education WIN sic Program, WIN is the nickname of the current mayor Sherwin Gatchalian). In 2010, the government, in partnership with the local school board, funded the purchase and construction of computer laboratories in 10 secondary schools all having a net worth of Php 17.7M (or about US$410,000 as of April 2011). This also includes the distribution of Php 1.46M (or about US$34,000 as of April 2011) computers in Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela and Valenzuela City Polytechnic College, as part of Department of Education's ICT4E Strategic Plan. In this project, information and communication technology education is extended and expanded among all students.[94] In 2009, the City Engineering Office repaired sidewalks and drainage to assist students especially during the wet season; they also repaired and constructed new buildings and classrooms to some schools in the city.[95] Under the same program, elementary school students received free mathematics and English workbooks published by the government especially designed for Valenzuelanos.[95] The steady increase of 3.4% enrollment rate each year forces the government to construct new buildings and classrooms to meet the target 1:45 teacher-to-student ratio, contrary to the current count of 1:50 ratio alternating in three shifts.[96] WIN ang Edukasyon Program was done in partnership with the Synergeia Foundation, a non-government organization that aims to improve education in local governments in the Philippines.[97]

At the same time, WIN ang Edukasyon Program also spearheads the yearly training of some mathematics and English language teachers assigned to Grades 1 and 2 pupils.[98] The seminar focuses on how to enhance reading skills, language proficiency and mathematics of the students they are teaching through re-acquaintance with various drills and activities. This was done with the efforts of lecturers from Ateneo de Manila University and Bulacan State University using the approach developed by the UP Diliman's College of Education.[99][100]

The government owns Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela and Valenzuela City Polytechnic College that serve as the city's state university and technical school for residents and non-residents respectively. The Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela (PLV) or University of the City of Valenzuela, was established in 2002 and is located within the perimeters of the old city hall in barangay Poblacion. In 2009, the city council passed Resolution No. 194 series of 2008 which authorized the government to purchase lots costing PhP 33M (or about US$750,000 as of April 2011) in nearby Children of Mary Immaculate College as part of the university's expansion.[101] Mayor Sherwin Gatchalian assisted the development, which has an over-all cost of PhP 75M (or about US$1.7M as of April 2011) loaned from Development Bank of the Philippines.[102] The newly purchased lots are used to construct an annex building which will house the departments of business administration and accountancy. The Board of Regents expected an increase of enrollment from 800 to 3,000 students in the next few years.[103]

Valenzuela City Polytechnic College (VCPC) was allotted with additional Php 18M (or about US$420,000 as of April 2011) budget in 2009 from the city fund which will be used for expansion and upgrade of the college.[95][104]

There are also privately owned academic institutions including the Our Lady of Fatima University (OLFU). OLFU was previously granted by Commission on Higher Education an autonomy, which includes independence from monitoring and evaluation services by the Commission though still entitled by subsidies and other financial grants from the national government whenever possible. The autonomous status of the university was approved on March 11, 2009, and expired last March 30, 2014.[105]

Healthcare

There are numerous hospitals in Valenzuela like the city-run Valenzuela City Emergency Hospital and the Valenzuela City General Hospital. There are also privately owned hospitals like Calalang General Hospital, Sanctissimo Rosario General Hospital and Fatima University Medical Center, a tertiary private hospital under the administration of Our Lady of Fatima University.[106][107][108] The soon-to-rise Valenzuela City West Emergency Hospital and Dialysis Center is located in barangay Dalandanan, adjacent to Valenzuela City Astrodome and Dalandanan National High School. It will render adequate healthcare services to underprivileged residents at a minimal fee.[109]

The city implements VC Cares Program which is designed for individuals who are unable to provide healthcare and basic necessities for themselves or meet special emergency situations of need.[110] While health care service and financial assistance are generally the forms of assistance given, these may be supplemented by other forms of assistance, as well as problem-solving and referral services. Appropriate referrals may be made to other agencies or institutions where complementary services may be obtained.[111]

According to the 2002 Commission on Audit, the city reported accomplishment per health center ranging from as low as 42.26% to as high as 206% and vaccine utilization of 33% to 90% compared to normal 46% to 377% per basic requirements.[112]

There are swampy areas on Valenzuela and there is a stagnant water in Tullahan River on the south, which make citizens vulnerable to mosquito-linked diseases such as dengue and malaria. Though malaria is not a common case in Valenzuela–the city ranks consistently among top five dengue-infected regions in the Philippines with around 560% chance of recurrence every year.[113][114] In the second quarter of 2008, however, only 500% increase was reported compared to the same period in 2007.[115]

In September 2009, the Department of Health distributed free Olyset anti-dengue nets treated permethrin insecticide to Gen. T. de Leon High School. Over 150 rolls of the nets were given and installed to the windows of the said school, as part of DOH's "Dalaw sa Barangay: Aksyon Kontra Dengue" (Visit Barangay: Action against Dengue) campaign.[116]

Shopping centers and utilities

On October 28, 2005, SM City Valenzuela was inaugurated.[117] Other shopping sites such as Puregold Valenzuela, the newly renovated South Supermarket and the newly opened Puregold Paso de Blas is also located in the city.[118][119] All these stores compete against each other since most have the same product offerings as diversified groceries except for SM City Valenzuela which has upgraded with the opening of The SM Store. People from the city with more major shopping needs normally head south to cities such as Quezon City and Manila, since they have bigger malls and commercial centers with more diverse trade goods.

Water supply for the city is supplied by the Metropolitan Water Works and Sewerage System (MWSS)' west concessionaire Maynilad Water Services, Inc (MWSI).[120][121] As of 2006, the city has at least 68% water service coverage as determined by the Regulatory Office of the MWSS.[122][123] Each customer receives at least 7 psi water pressure, which means supply can reach for up to two floors for residential use.[124] Maynilad is owned and currently operated by DMCI Holdings, Inc.–Metro Pacific Investments Corporation (DMCI-MPIC).[125]

On June 2, 2010, the Sitero Francisco Memorial National High School in barangay Ugong unveiled its first solar generators, the first time for a school in the Philippines. The six 1-kW photovoltaic solar arrays installed to light nine-classrooms are bought from Wanxiang America Corporation through the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE) and are part of the solar energy initiative of the city. The arrays were shipped from Illinois, installation were paid by the city government. First district representative Rex Gatchalian and former second district councilor Shalani Soledad headed the switching ceremony, that made it the first-ever solar-powered school in the country.[126][127] The solar panels can generate 1 kW to 5 kW of electricity per hour depending on the intensity of sunlight. Unused solar energy is stored in eight deep-cycle batteries which can be used after sunset. The panels also continue to absorb light from the night sky.[128]

Waste management

According to the 2002 Metro Manila Solid Waste Management Report of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Valenzuela has the highest number of identified recycling companies in the region.[129] It was also said that recycling centers related to plastic materials are relatively higher than other recyclable objects like metals, paper, glass among others.[129] Accordingly, the city government allocates an amount of about 785.70 Philippine pesos (approx. US$18 as of April 2011) for every transportation and collection costs of a ton of waste material. In 2003, the city generated about 307.70 tons of waste every day. In 2001, it was reported by ADB that the city has as high as 25% solid waste management cost recovery rate through service charges on households and other enterprises for operational activities associated with waste collection, treatment and disposal.[131] That same year, the city's proposal to implement a community-based solid waste management project in barangay Mapulang Lupa, was approved by the national government, which involves social mobilization, training of personnel, implementation of segregated collection and establishment of materials recovery facility and windows composting operation among others. The city government was granted a maximum of US$25,000 from Asian Development Bank for the operation of the project.[132]

In 1988, the city opened its first waste disposal facility, the Lingunan Controlled Dumpsite. Every year, the facility collects and processed only about 60% of the entire city's waste with landfilling and recycling services. The dumpsite uses rice hull ash as daily cover and odor control material for the waste collected in the area.[133] Lingunan Controlled Dumpsite also conducted some limited waste segregation and resource recovery operations prior to burial of residual waste.[133] In 2006, the controlled dumpsite was closed per MMDA order in 2003 and was subsequently converted into a sanitary landfill as directed by RA 9003.

In statistics, 60% of the wastes collected in the city are collected, hauled and dumped in controlled dumpsites while 5% are retrieved and recycled and 35% are thrown everywhere in the city. Half of all these wastes are non-biodegradable wastes which include plastics, Styrofoams and rubbers alike, while the remaining are biodegradable wastes which is 70% food and kitchen wastes, 20% plant wastes and 10% animal wastes.[134] In 2002, there are about 30 small and big junkshops that collect recyclable materials and 20 schools that require their students to bring recyclable stuff as school project.[134]

The city spearheaded Metro Manila's implementation of full-pledged waste management program in 1999 when it became the first area in the region to allocate 2.8-hectare land in barangay Marulas, to serve an ecology center and location for the city's waste management program's operation center. Biodegradable wastes in this area are converted to fertilizers.[135] In 2004, the city government funded the repair of 29 garbage trucks and purchase of another 20 trucks that may increase the capacity of Waste Management Office to do full rounds of garbage every week.[136]

Justice management

In a joint study conducted by the Supreme Court of the Philippines and the United Nations Development Programme in July 2003 assessing inmate and institutional management among selected municipal and city jails in the National Capital Region, it was found that Valenzuela City Jail has a congestion rate of 170%. According to the study, the excess number of inmates in Metro Manila jails resulted into outbreak of various ailments such as psychiatric disorders, pulmonary tuberculosis and skin diseases. The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology recommends the implementation of release programs under applicable laws.[137]

The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) of Valenzuela is located along Valenzuela Hall of Justice in barangay Karuhatan.[138] It was formerly located at the old city hall in barangay Maysan which was transferred by mayor Sherwin Gatchalian in 2010 along with other trial courts, the police headquarters and prosecutor's office of the city.[139] That same year, the BJMP launched the Alternative Learning System program, in partnership with the local government and Department of Education (DepEd), as part of the rehabilitation programs to city jail inmates. Successful passers of the program received certification of DepEd as proof of completion of secondary education.[140]

Transportation

Expressways such as the North Luzon Expressway (NLEX) and NLEX Harbor Link project traverse through Valenzuela. Valenzuela is accessible to and from NLEX via Paso de Blas Interchange, formerly known as Malinta Exit (due to the road's direct access to barangay Malinta), at Km. 28. It also has exits towards barangays Lingunan and Lawang Bato. Meanwhile, the Harbor Link project, where Segments 8.1 and 9 are components of Circumferential Road 5, provides access to Valenzuela through its interchanges at MacArthur Highway (Karuhatan), Smart Connect Interchange with NLEX, and Mindanao Avenue in barangay Ugong, as well as exits towards barangays Parada and Gen. T. de Leon.[141][142]

Valenzuela is also connected to Bulacan through MacArthur Highway which ends at Bonifacio Monument in Caloocan.

One of the well-known bridges in Valenzuela is the Tullahan Bridge in barangay Marulas that connects the city to barangay Potrero in Malabon.[48] Tullahan bridge is part of MacArthur Highway that was built during the Spanish era as a way of transporting vehicles over Tullahan River. In the span of years, it was renovated repeatedly, most recent was in 2008, though defects on the bridge began to appear barely six months after it opened for public use.[143][144][145]

The city is webbed by hundreds of roads where 99.622% of them has a surface type of concrete while the remaining 0.378% were made of dirt.[146] The Department of Public Works and Highways recognizes nine national bridges in Valenzuela, listed below.[147] Other bridges are just minors that connect small cliffs and former landfill areas, like Malinta Bridge in barangay Malinta. City roads has an average road density of 1.155 kilometer of road per 100 square-kilometer of land area. Each road has an average road section of 155 sections and spans 54.267 km.[146]

The Valenzuela Gateway Complex Terminal in Paso de Blas is designated by the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority as Manila's northern provincial bus terminal. Bus companies also founded terminals in barangay Malanday, northernmost locality of Valenzuela along the border with Bulacan, though there are terminals situated in barangays Dalandanan and Karuhatan as well. This includes Laguna Star Bus, PAMANA Transport Service, Inc., CEM Trans Services and Philippine Corinthian Liner, Inc. among others. These buses are lined with Metro Manila destinations only, usually in Alabang or Baclaran with routes along EDSA. Bus traffic is also dense at barangays Paso de Blas and Bagbaguin due to its proximity to KM 28 NLEx Interchange and bus terminals in Novaliches, Quezon City. Other modes of transportation includes jeepneys (with routes usually from Malanday to Recto, Santa Cruz, Divisoria, Pier 15 South Harbor & T. M. Kalaw in Manila and Grace Park & Monumento in Caloocan and Malinta to Malolos City, Baliuag and Santa Maria along MacArthur Highway) for general mass transportation, tricycles (or trikes) for small-scale transportation and taxicabs for upper middle classes.

External relations

Valenzuela is twinned with the following towns and cities:

| Country | Place | Region / State | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | |||

| 2008 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2012 | |||

| 2013 | |||

| 2013 | |||

| 2013 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2014 | |||

| 2015 | |||

| 2015 | |||

| 2015 | |||

| 2015 | |||

| 2016 | |||

| 2016 | |||

| 2016 | |||

| 2017 | |||

| 2017 | |||

| 2017 | |||

| 2018 | |||

| 2018 | |||

| 2019 | |||

| 2019 | |||

| 2019 | |||

| 2019 | |||

| 2020 | |||

Friendship links

Valenzuela has friendship links (with no formal constitution) with the following towns and cities. Agreements usually forged towards industrial, cultural or academic exchanges and understanding.

Yangzhou, Jiangsu China[149][154]

Yangzhou, Jiangsu China[149][154] Kauai, Hawaii, United States[155]

Kauai, Hawaii, United States[155]

Notable people

- Atty. Santiago San Andres de Guzman, Municipal Mayor from 1988 to 1992.

- Virgilio "Billy" Abarrientos, member of the Crispa Redmanizers.

- Eugenio Angeles (1868-1977), former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines from 1967 to 1968.[156]

- Bobbit Carlos (born 1957), former mayor (1995-2004) and representative (2004-2007).

- Danilo L. Concepcion, former youth sector representative to the Interim Batasang Pambansa (1978-1984), former Vice President for Legal Affairs of University of the Philippines, Dean of UP College of Law since 2011, and concurrently President of the University of the Philippines since 2017.

- Glaiza de Castro (born 1988), Filipina actress and singer.

- Ford Valencia (born 1995), Pinoy Boyband Superstar winner, member of Boyband PH.

- Gerard "Gerry" Esplana (born 1966), former athlete (1993-2003), former member of Presto Tivolis, Santa Lucia Realtors and Shell Turbo Chargers, and former city councilor (2004-2013).

- Franzen Fajardo (born 1982), actor, TV host, and former reality show contestant.

- Florentino V. Floro, Jr. (born 1953), former judge.

- Win Gatchalian (born 1974), former mayor (2004-2013), representative (2001-2004, 2013-2016) and Senator of the Philippines since 2016.

- Roberto "Bobby" Jose, member of the 1989 Petron Blaze Boosters Grand Slam team and was the PBA All Star during his rookie year.

- Charee Pineda (born 1990), actress and city councilor since 2013.

- Ignacio Santiago, Sr., former mayor (1956-1959 and 1964-1967) of Valenzuela, then governor of Bulacan from 1968 to 1986.[157]

- Pablo Santiago, Sr. (died 1998), film director and producer.

- Randy Santiago (born 1960), actor, television host, singer, songwriter, producer, director and entrepreneur.

- Raymart Santiago (born 1973), action star and comedian.

- Guillermo S. Santos (1915-1991), former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1977 to 1980.[158]

- José Serapio, former mayor (1912-1917) and former governor of Bulacan (1900-1901).[159]

- Shalani Soledad (Shalani Soledad-Romulo) (born 1980), former city councilor (2004-2013) and TV personality.

- Pío Valenzuela (1869-1956), physician, patriot, writer and member of the Katipunan society. Namesake of Valenzuela.

See also

References

- "Letter to the Director of the NHCP". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- "ARAW NG VALENZUELA 2012 Kasaysayan, Kasarinlan, Kaunlaran" (in Tagalog). Museo Valenzuela. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- "Executive Summary of the 1999 Annual Audit Report on the City of Valenzuela". Commission on Audit. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- City of Valenzuela | (DILG)

- "Province: NCR, THIRD DISTRICT (Not a Province)". PSGC Interactive. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Census of Population (2015). "National Capital Region (NCR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "PSA releases the 2015 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates". Quezon City, Philippines. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- "Republic Act No. 8526 An Act Converting the Municipality of Valenzuela into a Highly-Urbanized City to be Known as the City of Valenzuela". Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- "Valenzuela celebrates 13th cityhood anniversary on Monday". Bayanihan.org. 14 February 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "Local Government and Taxes:Cities and their income classification (1993, 1995, 1997, 2001, 2005)". Democracy and Governance in the Philippines. Archived from the original on 2010-04-10. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- Catapat, Willie (16 August 2005). "China official, traders visit Valenzuela industrial sites". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Hanks, Patrick (2003). Dictionary of American Family Names (e-reference ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508137-4. Retrieved 26 April 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-508137-4. Alternative URL can be found in Ancestry.com

- "Dr. Pio Valenzuela, 1869–1956". Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- Alvarez, Carolina & Malay 1992, p. 6

- Arenas 1997, p. 33

- Arenas 1997, p. 34

- Arenas 1997, p. 36

- "City Ordinance 03: An Ordinance Declaring November 7 and Years Thereafter as Valenzuela Foundation Day". Valenzuela City Council. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Arenas 1997, p. 39

- Arenas 1997, p. 42

- Arenas 1997, p. 47

- Arenas 1997, p. 46

- Diocese of Novaliches

- Arenas 1997, p. 48

- https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=10215303585008491&id=1401141105

- "Supreme Council Record of meeting held on February 1, 1896, in Polo". Archivo General Militar de Madrid: Caja 5677, leg.1.20. Katipunan Documents and Studies. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Guillermo, Artemio R. (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810872462.

- Arenas 1997, p. 50

- Sagmit 2007, p. 156

- "Pio Valenzuela (1921-1925)". Province of Bulacan, Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- Tiongson 2004, p. 109

- Tiongson 2004, p. 196

- Duka 2008, p. 180

- Arenas 1997, p. 52

- Arenas 1997, p. 54

- Arenas 1997, p. 56

- Arenas 1997, pp. 55–56

- Arenas 1997, p. 58

- "Project Study June 2009" (PDF). Timog Hilaga Providence Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Mahilum, Ed (12 February 2011). "Valenzuela to mark 13th year with mega jobs, trade fairs". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- "An Act Declaring February 14 of Every Year a Special Working Holiday in the City of Valenzuela to be Known as "Araw ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela"". Philippine Congress. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- "Valenzuela mayor, 6 others ordered dismissed over Kentex blaze". The Philippine Star. 5 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Saunar, Ivy (15 May 2015). "Kentex blaze 3rd worst fire incident in Philippines - BFP". CNN Philippines. CNN Philippines. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "Valenzuela City: The City". Valenzuela City. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Carcamo, Dennis (28 September 2010). "MMDA partners with private firm for Tullahan River dredging". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- "An Anvil Award for the MNTC Tullahan River Adoption". Eco Generation World Environment News. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- "Tenejeros River can easily be saved". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- Calalo, Arlie (27 November 2010). "DENR, SMC ink pact to save Tullahan River". The Daily Tribune. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- Mahilum, Ed (22 September 2010). "Group Formed to Clean Up Tullahan River". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- INSIDE STORY: Building resilience to climate change locally – The case of Valenzuela City, Metro Manila

- "Climate Information and Statistics". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration.

- "Weather > Philippines > Manila". BBC Weather. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- "Climate: Valenzuela - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- de Guzman, Constancio (2005). "Farming in the City: An Annotated Bibliography of Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture in the Philippines with Emphasis on Metro Manila" (PDF). University of the Philippines Los Banos. International Potato Center. p. 41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "Ecotourism Sites in National Capital Region". Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 2012-04-24. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Carvajal, Nancy (3 March 2008). "Birds find nesting place in Valenzuela City". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Natividad, Beverly (9 January 2010). "Valenzuela offers best spots in Metro for local anglers". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Rempollo, Jay (1 January 2008). "SC Names Environmental Courts". Supreme Court of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 22 December 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Landsberg 1965, p. 41

- "Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- "National Capital Region Police Office – History". National Capital Region Police Office. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- "Valenzuela City Ulat sa Bayan 2004 -2013" (PDF). City Government of Valenzuela. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Census of Population and Housing (2010). "National Capital Region (NCR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Censuses of Population (1903–2007). "National Capital Region (NCR)". Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Province/Highly Urbanized City: 1903 to 2007. NSO.

- "Province of Metro Manila, 3rd (Not a Province)". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Population of 11.9 Million was Recorded for National Capital Region (Results from the 2010 Census of Population and Housing)". Philippine Statistics Authority. 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Household Population by Age Group and Sex by City/Municipality: National Capital Region, 2010" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Population and Annual Growth Rates for The Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities Based on 1990, 2000, and 2010 Censuses" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Himig Valenzuela on YouTube

- "Republic Act 7160, otherwise known as the Local Government Code of 1991 (Philippines)". The LawPhil Project. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- Torda, Jehan (12 September 2008). ""Himig Valenzuela" MTV Premiered". Valenzuela Public Information Office. Retrieved 22 April 2011. Web cached using Google cache service.

- "Bayang Valenzuela". Facebook. Valenzuela City Cultural and Tourism Development Office. March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "An Act Declaring February 14 Every Year a Special Working Holiday in the City of Valenzuela to be Known as "Araw ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela"". Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "Valenzuela Travel guide, Philippines". Travel Grove. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- Vanzi, Sol Jose (2 May 2000). "Valenzuela San Roque Festival starts tomorrow". Headlines News Philippines. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- –, Sidney (13 May 2006). "Feast of San Roque, Mabolo, Valenzuela City". Archived from the original on 2006-06-14. Retrieved 12 May 2009.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Mano Po San Roque Festival". Department of Tourism. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "Paraiso Philippines>>Valenzuela City". Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- Catapat, Willie (14 November 2009). "Polo fiesta Valenzuela's grandest". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- Vanzi, Sol Jose (6 November 2001). "Valenzuela City honors "Putong Pulo"". Philippine Headline News Online. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Luci, Charissa (11 November 2004). "4th Putong Polo fest launched tomorrow in V'lenzuela City". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- PIO, Administrator, Team. "People's Park to open in Valenzuela City on Valentine's Day". City Government of Valenzuela. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- March 14, Susan G. De Leon Published on; 2019. "Valenzuela opens new family park". Philippine Information Agency. Retrieved 2020-03-26.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Valenzuela marks greener, upgraded, historic Polo Park". Manila Standard. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- "Valenzuela Tourist Attractions". Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Valenzuela Sights and Landmarks Guide, Philippines". Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "Towns and Cities – Valenzuela". Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- Darang, Josephine (6 May 2007). "Purely Personal : Catholics mark 90th Fatima anniversary". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- Uy, Jocelyn (24 February 2011). "EDSA 'Fatima' blessed by Pope; Sin fetched image in NJ". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2011-02-25. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- Lao, Levine (17 January 2011). "Marian devotion, modern Filipino art blend in Valenzuela exhibit". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2011-04-11. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- Aquino, Leslie Ann (29 May 2010). "Our Lady of Guadalupe now a national shrine". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- Ruiz, JC Bello; James Catapusan; Willie Catapat (31 July 2009). "Prayer vigil for Cory ends". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- Cayabyab, Marc Jayson. "Valenzuela opens first fishing village". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- "Valenzuela local gov't provides computer labs to 10 more public high schools". Positive News Media. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Caiña, Zyan (1 June 2009). "Valenzuela City students to benefit from new school facilities". Valenzuela Public Information Office. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Laude, Pete (30 May 2009). "Valenzuela opens 1st newly built classrooms". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "Win ang Edukasyon sa Valenzuela City". Synergeia Foundation. Archived from the original on 2011-11-12. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "(Metro News) Valenzuela teachers complete training seminars". Balita.ph. 5 March 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Catapat, Willie (14 August 2009). "300 Valenzuela teachers trained on reading skills". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "250 school teachers complete training". Ateneo de Manila University. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Caiña, Zyan (28 May 2009). "Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela undergoes expansion". Valenzuela Public Information Office. Retrieved 27 April 2011. Web cached from Google cache service

- David, Gigi (29 May 2009). "Valenzuela upgrading city-owned college". Manila Standard Today. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- PNA (24 June 2008). "Two newly-opened 'Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela campuses benefit 3,000 students". Positive News Media. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "Valenzuela allots P18 M to upgrade its Polytechnic College". Positive News Media. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Roy, Imee Eden F.; Arlene H. Borja (April–July 2009). "Fatima is now Autonomous". The Fatima Tribune. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "Fatima University College of Medicine". Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Sanctissimo Rosario General Hospital (business site)". Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Calalang General Hospital's location map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-26. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- Guiang, Alfred (23 September 2011). "New Valenzuela hospital to give wider healthcare coverage to Valenzuelanos". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Special Services-VC Cares Program". Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "VC Cares conducts feeding program for children in depressed areas". Public Information Office. 26 July 2007. p. 3. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Sectoral Performance Audit Report on the Polio Immunization Program of the City of Valenzuela (CYs 2001–2002)". Commission on Audit. 2002. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- Ortiz, Margaux (6 September 2006). "Metro records highest dengue incidence – DoH". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- "DOH lauds Manila for low dengue rates". Media Bureau. 4 August 2008. Archived from the original on 10 August 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "DOH chief visits Valenzuela amid rise in dengue cases there". GMA News (in Tagalog). GMA Network. 23 July 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2009., in video.

- Caiña, Zyan (16 September 2009). "Gen. T. De Leon National High School Receives IT Nets from DOH". Valenzuela Public Information Office. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- "Mall List-SM Valenzuela". Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- "Puregold Valenzuela location map". Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- "EYP.PH List of malls in Metro Manila". Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- "More Than Just Water: Maynilad Annual Report 2009" (PDF). Maynilad Water Services. p. 3. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- "Maynilad Business Area". Maynilad. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Minogue & Cariño 2006, p. 267

- Cuaresma, Jocelyn (June 2004). "Pro-Poor Water Services in Metro Manila: In Search for Greater Equity" (PDF). Manchester: Centre on Regulation and Competition, University of Manchester. p. 4. Retrieved 11 December 2011.